Korykos

Coordinates: 36 ° 27 ′ 55 ″ N , 34 ° 9 ′ 15 ″ E

Korykos ( ancient Greek Κώρυκος , Latin Corycus ) was an ancient city on the coast of Cilicia . It was located at what is now the Turkish resort of Kızkalesi in the Mersin province . The place has been since the 2nd century BC. Known and first belonged to the Seleucids , then to the Roman Empire . After a troubled time under the control of the Cilician pirates , the place was under Byzantine rule and flourished economically in Christian times. The city fell into disrepair in the 10th and 11th centuries until Byzantium built the country castle in 1099 . From the 12th century it belonged to the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia with the construction of the sea fortress , later to Cyprus , until the city was finally conquered by the Karamanids , Mamluks and in 1482 by the Ottoman Empire .

Since the 19th century, the rough Cilicia has been the destination of many western travelers and archaeologists. From the beginning of the 20th century, the city of Korykos with its buildings and inscriptions was extensively researched. Extensive, largely overgrown fields of ruins can now be seen from the important port city. These include numerous churches, remains of the city wall and three extensive necropolises with rock tombs and sarcophagi . The land and sea fortresses from the late Byzantine and Armenian times are preserved as ruins. There are only a few remains of buildings from Roman times, but in the Christian buildings and especially in the country castle, numerous components from earlier times are used as spoilage .

Since 2014, Korykos has been on the tentative list of applicants for UNESCO World Heritage status .

location

The port city of Korykos was near today's Kızkalesi, in the Rough Cilicia in the area between the rivers Kalykadnos (today Göksu ) in the west and Lamos (today Limonlu Çayı ) in the east. The neighboring port cities are in the west Seleukia on Kalykadnos, today's Silifke , and Korasion ( Atakent ) and in the east Elaiussa Sebaste ( Ayaş ) and Lamos ( Limonlu ). In the mountainous hinterland there are numerous places from the Hellenistic to Byzantine times, almost all of which belonged to the sphere of influence of the priestly state of Olba and Diokaisareia . The latter can be recognized by the appearance of Olbic symbols on various buildings and especially on towers. These include Cambazlı , Çatıören , Öküzlü , Emirzeli , Işıkkale , Tekkadın , Mancınıkkale and Kanytelleis . However, the influence of the priestly state never extended to Korykos or any of the other port cities mentioned. A ring of five towers ( Akkum , Boyan , Gömeç , Sarayın and Yalama) stretches around Korykos and Elaiussa Sebaste, who took turns as the metropolis of the region around the turn of the millennium . They served to ward off enemies, but were at the same time developed as storage and residential towers that were used by the population as a retreat in the event of attacks. These towers bear Olbian marks, which suggests that, among other things, they were supposed to protect the Olbian territory against attacks by the Cilician pirates .

About five kilometers west of Korykos are the Koryk Grottoes (Greek ιωρύκ [ε] ιον ἄντρον Korykion Antron ), now called Cennet ve Cehennem (Turkish for "heaven and hell"). The two sinkholes were created by an underground river that also flows underground into the Mediterranean at Narlıkuyu , two kilometers west of Kızkalesi. In Greek mythology , the battle between Zeus and the monster Typhon is located there. The larger of the two sinkholes is accessible, it was already known in antiquity for the saffron growing there and is mentioned by Strabo . Above the grotto are the remains of a temple of Zeus Olbios or Zeus Korykios, on the northeastern ante of which lists of Olbian priestly rulers are carved.

In the steep face of the Şeytan Deresi valley , which stretches inland in Kızkalesi west of Korykos, a group of rock tombs with remarkable reliefs, called Adamkayalar , is carved about three kilometers away . A similar grave wall with the name Yapılıkaya can be found about two kilometers east of it in a parallel valley . In some of the tombs a number of the names from the priestly lists of Korykion Antron are repeated in the inscriptions, so that it can be assumed that some of the Olbian rulers are buried here.

The Roman coastal road from Side to Seleukia Pieria ran through Korykos, and a road to Cambazlı and Olba branched off in the village to the north. After the establishment of the province of Cilicia, the roads were renewed under Vespasian ; for the coastal road to Korasion, ravines were cut in the rock. It is noteworthy that both this section and the path leading to the north were stepped in places, i.e. not suitable for driving with wagons, but only for pedestrians, riders and pack animals.

Names

In addition to the Greek Korykos and the Latinized Corycus, the place had different names over time. In Byzantine times he was called Gorhigos or Kourikos (by the historian Leontios Machairas ). The Arabic name was Qurquš ( al-Idrisi ), the Armenian Gurigos or Gorigos . Franconian names were Cure ( Wilbrand von Oldenburg ), Curta, Culchus, Curchus and Le Courc . In the Portolan Rizo of 1490 it is referred to as Churcho , in other Italian nautical charts as Curcho, Curco or Colco .

Research history

The British captain Francis Beaufort , who explored the Cilician coast on behalf of the Admiralty in the years 1811-12, delivered the first report on Korykos and the surrounding area. After Alois Machatschek's "very imaginative steel engravings" by Léon Marquis de Laborde in 1838, the Cilician travelogue of the French orientalist Victor Langlois followed in 1861 with the first scientific description of the region and the place. This was followed by research trips and publications on western Cilicia by Louis Duchesne and Maxime Collignon (1877), Louis Duchesne (1883), James Theodore Bent (1891) and Edward L. Hicks (1891), who copied numerous inscriptions. This was followed by Rudolf Heberdey and Adolf Wilhelm in 1896 , Gertrude Bell in 1906 , Ernst Herzfeld in 1907/1909 and Roberto Paribeni and Pietro Romanelli in 1914 .

Ernst Herzfeld and Samuel Guyer published the first study in 1930 that dealt specifically with Korykos. In it they described all buildings in the city with the exception of the necropolis. In the following year 1931 Josef Keil and Adolf Wilhelm provided an almost complete record of the grave and other inscriptions of the place, without, however, dealing with the grave structures. The Austrian building researcher Alois Machatschek caught up with the latter in 1967 . Friedrich Hild and Hansgerd Hellenkemper visited Korykos several times between 1968 and 1989 and published the results in various publications. As part of a survey by the University of Maryland's School of Architecture in the 1990s, a few dives were made in the port area of Korykos in 1995, during which the remains of the jetties that led from the country castle and from the western end of the bay to the island castle were examined were taken. In addition, there was an examination of the port facilities and other architectural remains east of the rural castle, where the city's first port is believed to be. Between 2004 and 2011, the Kilikia Arkeolojisini Araştırma Merkezi (Research Institute for Cilician Archeology) of the University of Mersin, under the direction of Serra Durugönül, carried out surface surveys in the area of the city and the hinterland.

history

The area between Kalykadnos and Lamos came after the conquest of Cilicia by Alexander the Great after 333 BC. Under Hellenistic influence. In the Diadoch Wars after Alexander's death, rulership changed over the region several times. Korykos was first mentioned for the year 197 BC. Mentioned as Antiochus III. Cilicia was conquered by Ptolemy V in the Fifth Syrian War for the Seleucid Empire . When in the second half of the 2nd century BC When the Seleucids had to hand over dominance to the Roman Empire and the Romans neglected the area, the pirates of the eastern Mediterranean settled in the Cilician coastal areas. 102 BC BC Antony was sent as praetor to fight the Cilician pirates , conquered a part of Cilicia and made it the Roman province of Cilicia. Only after Pompey in 67 BC B.C. had defeated the pirates, the problem was eliminated. The fact that Korykos was already an important city in Roman times, which also exercised the right to mint, is proven by mentions from Cicero , Livius and Pliny . Remnants of some buildings from this period such as temples, colonnaded streets, a nymphaeum and a splendid gate built into the country castle have been preserved.

For a long time Korykos was in rivalry with the neighboring Elaiussa Sebaste , in the 3rd century AD it had lost its importance and was relegated from the polis to the Kome (small town). After the siege of the two cities in 260 by the Sassanid ruler Shapur I and the battles that followed, a troubled period began in Cilicia, reinforced by the uprisings of the Isaurian mountain peoples. In the following Christian period, which began in Cilicia before Constantine , the region initially suffered from the persecution of Christians . After Christianity was recognized under Constantine and became the state religion at the end of the 4th century , Korykos regained supremacy and the area experienced an economic boom. This was evident, among other things, in the reconstruction of the nearby town of Korasion to the west , in the construction work for the aqueduct that supplied Korykos and Elaiussa Sebaste with water from the Lamos, and in particular for Korykos in the ongoing construction activity in the city area, during which numerous remarkable church buildings were built . Stephanos of Byzantium called Korykos the most important city in the Seleukeia district . The place was suffragan of Tarsus . The first attested bishop was Germanus at the Council of Constantinople in 381. Also at the Council of Ephesus in 431 as well as at the Synod of Constantinople in 536 and the councils there in 553 and 680/81 , bishops of Korykos are recorded as participants. At the instigation of Bishop Indakos, Emperor Anastasios I issued an ordinance around 500 in which the provincial government was prohibited from voting for the defensor ( ἔκδικος ekdikos ) - an official who mediated between the city and the central government - and the curator ( ἔφορος ephoros ) to interfere. The inscription is engraved on two Roman altar stones in secondary use, which were later built into the entrance of the country castle as spolia .

Since the division of the Roman Empire into East and West Rome in 395, Cilicia and thus Korykos belonged to the Eastern Roman-Byzantine Empire. During the reign of Emperor Justinian I , Byzantium (Ostrom) got into battles with the Sassanid Persian Empire. After a Persian invasion of Cilicia (540) the area had to endure another period of unrest. Even if Korykos was not directly affected by the fighting, construction activity declined noticeably. In 698 the place belonged to the Byzantine theme of the Kibyrrhaiotai and was a naval base. From 9/10 In the 19th century it was part of the Seleukeia theme. Then the place fell into disrepair. In an Arabic itinerary of the 10th century it is mentioned as Qurquš together with Korasion among the ruinous Greek sites on the Cilician coast. In 1099, the Megas Drungarios (fleet commander) Eustathios built a fortress on the western edge of the ruined town on the orders of the Byzantine emperor Alexios I , at the same time as the castle of Seleukeia , which was supposed to secure the empire's passage via Cyprus to the Holy Land .

The city experienced a late heyday when it was presumably conquered by the Armenian King Constantine I at the beginning of the 12th century and after a short reconquest by Byzantium it belonged to the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia . The Seeburg was built under his king Leon II (1187–1219), as can be seen from an inscription there that Victor Langlois published in 1861 and which is lost today. On the fief list Simon appears from Kiwrikos Leon, his successors were a Gottfried and his son Vahram. Again churches and other buildings were built. After Leon's death and the ensuing disputes, Oschin, the founder of the Hethumid dynasty , was followed by his son Gregorios and his son Hethum , who is also known as a historian. For Korykos there is evidence of trade with Venetians and Genoese at this time , but as a trading center it lagged behind Lajazzo (now Yumurtalık ), which is also a small Armenian . Carpets and saffron from the Koryk grottoes are known as trade goods . After a first advance of the Mamluks up to Korykos in 1275, Lajazzo was conquered by them in 1322, whereupon numerous residents fled to Korykos. After the murder of the last Hethumid prince Oshin of Korykos in 1329, the city returned to the possession of the crown.

When Korykos was threatened by the Karamanids in 1361 and the power of the Armenian rulers was dwindling, the inhabitants turned to King Peter I of Cyprus for help. He sent the English knight Robert von Lusignan to Korykos. After a successful defense, the inhabitants swore the oath of fief to Peter, probably in the cathedral. In 1367 another attack by Karaman was repulsed. King Peter I had the iron gates of Tripoli and Tortosa brought to the fortress from his campaigns . Since the customs house of Korykos received 3,000 to 4,000 ducats annually , Thibald Belfarage tried in 1375 to get it as a fief from the king, but was rejected. In the same year Sis was conquered by the Mamluks along with the last small Armenian possessions in Cilicia, Korykos remained as the only Christian place under the Lusignans in Cypriot hands. In 1448 the Karamanids finally succeeded in conquering, in 1482 it came to the Ottoman Empire . After that there was no more news about the place, only on nautical charts from the late Middle Ages the place was still recorded as " Κοῦρκος , Curcum, Curcho " or " Churcho ".

Hermes cult

The Graeco-Roman poet Oppian , possibly a son of the city, but according to other sources from Anazarbos , called Korykos "City of Hermes" in the 2nd century AD. The cult of Hermes was widespread in Cilicia. Already in the 2nd millennium BC The Luwian god Runtiya was worshiped, who was equated with Hermes in antiquity . In some older names of the priestly lists of Korykion Antron, which are of Luwian origin, Runtiya appears as a part of the name (e.g. Ρωνδβιης Rondbies "Runt (a) -Gabe"), as does the Luwian weather god Tarhunz (e.g. Τροκοζαρμas .ς Trokozarmarm) "Tarhu (nt) protection"), who is identified as Zeus. In Hellenistic and Roman times there were sanctuaries of Hermes in Çatıören, in Yapılıkaya and in Örenköy in the northern valley of the Lamos. The symbols associated with Hermes, kerykeion and phallus, are among the Olbic symbols that are common in the region. Hermes or one of his attributes is also depicted on numerous coins. No archaeological evidence of Hermes has been found in Korykos itself.

Jewish community

From the grave inscriptions of the necropolis of Korykos it is evident that at least from the Roman period a notable Jewish community existed in the city. In 1931, Keil and Wilhelm identified ten of the more than 500 inscriptions they had published of Jewish origin. Margaret H. Williams recognized two more in 1992 and Serra Durugönül was able to recognize 21 of the known inscriptions as Jewish in 2012. Criteria for classification as Jewish graves were initially an engraved menorah and the names Ἰουδαΐος (Ioudaïos) or Ἑβρέος ( Hebreos ). The other grave inscriptions were recognized by Williams and Durugönül because of their location and especially the names of the buried, which were of Jewish origin, for example Iakobos, Samouelos, Zakharia, Soul, Sabbatios, Isakios and Abramios. This also made it possible to gain knowledge about the professions of the Jewish residents. These included wine and oil traders, weavers, flax and wool spinners, but also a goldsmith, a stonemason, a potter and workers in the port.

Margaret Williams concludes from the ten inscriptions recognized as Jewish by Keil / Wilhelm on a different self-image of the Koryk Jews in Roman and Christian times. Since the social or political functions of the buried were placed more in the foreground in the earlier grave inscriptions, she considers the Jews in Roman times to be further integrated into Roman society. In the later graves, those buried are more often defined by their duties and offices within the Jewish community, in which they see a certain pride in Jewish identity. It is undisputed that there was no isolation from the rest of the population at any time. The Jewish graves are randomly scattered between the other graves, occasionally Jewish sarcophagi were used as burial places for Christians or Roman citizens or vice versa.

Building the city

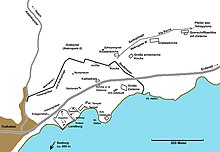

The ruins of Korykos adjoin the Kızkalesi area to the east and lie on both sides of the modern road to the sea in the south. The city wall began in the west in what is now the modern built-up area, stretching in a wide arc to the northeast and back to the south to the coast about a kilometer further east. The land fortress, which was probably built over a Roman forum, is located directly by the sea on today's beach. To the east of it are the remains of two temples, various unidentifiable buildings and a large open cistern. North of the street within the city walls are the cathedral, two smaller, presumably Armenian churches and the church above the cistern. In this area of non-sacred buildings, Herzfeld mentions a nymphaeum, the remains of a colonnaded street and an unclear building. Outside the city wall, a path known as the Via Sacra runs approximately to the east, on which there are three remarkable churches, from east to west the transept basilica, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the monastery church. Remnants of the Great Armenian Church are close by. Sarcophagi and individual rock graves are distributed on both sides along the western city wall, in the north there is another extensive necropolis. There are also numerous well-preserved sarcophagi along the Via Sacra. The sea fortress is located about 600 meters southwest of the country castle on an offshore island. Both castles were probably connected by a pier.

Hellenistic and Roman buildings

The relics from the Hellenistic and Roman times form the smallest part of the buildings of Korykos, they are largely overbuilt by later buildings. The core of the ancient city can probably be located on the ledge on which the country castle was later built. However, numerous elements of ancient buildings are contained as spoils in Byzantine and Armenian buildings. A remarkable Roman component is the grand gate integrated into the western wall of the country castle. According to Guyer and Herzfeld, it marked the beginning of a colonnaded street that led to the temples east of the fortress. After Hellenkemper and Hild, the Cardo maximus began there , the main axis of the ancient city. A large number of column shafts, which are decoratively built into the walls and towers of the castle, therefore belonged either to the columned street or to buildings of the Roman forum , which is assumed to be at the site of the country fortress. The gate stands out from the adjoining medieval masonry with its neat cuboid structure. Its outer facade was divided into three parts by four pilasters with acanthus capitals . In the middle two smaller pilasters carried the 5.90 meter wide archway. In each of the side surfaces there was a niche with side pilasters and a gable. The lower end of it was a protruding console, which indicates that statues were erected there. The upper end of the gate was formed by an entablature made of a three-part architrave , transition profile and frieze, egg bar and row of teeth , above which acanthus-adorned consoles carried the geison closed with a sima . The gate is dated to the late 2nd or 3rd century AD, the masonry has been restored.

Only sparse remains of the foundation walls can be seen of two temples east of the castle grounds. Remains of a nymphaeum in the Gräbertal, parts of the port facilities east of the country castle and traces of columned streets also go back to Roman times, as well as some indefinite remains of buildings in the east of the city. It cannot be proven whether there was already a city wall, the remains are from the 4th century. A coin of the city from early autonomous minting, 1st century before or after Christ, which shows a tyche with a wall crown, suggests that an early, possibly Hellenistic city wall existed. There is no archaeological evidence for this. A round tower by the sea about 600 meters east of the country castle, about 3.50 meters in diameter and still 5-6 meters high, is regarded as the end tower of the city wall, which turned there as a sea wall to the west. In the area, in addition to the remains of this wall, there are also ship landing stages and stairs carved into the rock, which probably belonged to the earlier port facilities of the city. It is not possible to determine the exact time from which the systems originate. Later on, the port moved to the larger bay west of the land fortress.

The rock graves , burial houses, sarcophagi and chamosoria of the three necropolises cover a period from the turn of the ages to the 7th century and are discussed separately .

Late Roman and early Byzantine buildings

Since the 4th century Korykos experienced an economic boom, probably also as a trading center and transshipment point for the hinterland. During this time, the new city wall was built, which encircled the city area in a wide arc from the port in the west of the fortress. The aqueduct with several aqueduct bridges , which had been supplying the place with water from the Lamos together with Elaiussa Sebaste since the imperial era , was renewed and considerably expanded. The line reached the city walls from the east, roughly following the course of today's street. At the same time, numerous cisterns were built in the city , including in the 5th / 6th Century the large high cistern in the east of the city with a polygonal floor plan and dimensions of about 60 × 40 meters. The pier, which cannot be precisely dated, protrudes from the headland on which the ancient city center was located and into the sea in the direction of the offshore island, probably arose during this time, possibly as a reaction to the increasing siltation of the port.

A clear sign of the city's prosperity are the numerous - Hellenkemper / Hild speak of at least twelve - impressive sacred buildings that were built after the 4th century, after Christianity had become the state religion in the Roman Empire from 380 onwards. Through the missionary work of Paul of Tarsus , among other things , Christianity found followers in Cilicia early on. Most of the churches are three-aisled basilicas . Within the city walls, the cathedral and the church stand above the cistern. Three large churches from this period stand extra muros on the Via Sacra: from east to west the transept basilica, the Holy Sepulcher and the monastery church. There is a burial chapel about 1.6 kilometers east of the country castle. Other churches, also in the area of the country castle, are of a later date as Armenian and medieval buildings.

cathedral

The cathedral is centrally located in the urban area of Korykos, today directly north of the thoroughfare. Only the apse rises up between the tall trees and bushes . Guyer describes it as "the oldest and most beautiful of the churches of Korykos preserved within the city walls" and therefore considers it the cathedral where the city's bishops officiated and where the residents swore oath of allegiance to King Peter I of Cyprus in 1361. It is a three-aisled columned basilica with dimensions of 19.50 × 32.20 meters. The excavations of Herzfeld showed in the west a narthex that was 4.60 meters deep and took up the entire width of the church with an apse on the north side, the entrance of which was a tribelon . It was divided into three parts according to the naves by pilasters that were probably connected with arches . The middle part opened outwards through three arches supported by columns. As in the main room of the church, no references to an upper floor were found, which is why a pent roof is assumed to be the upper end . The naos was divided into three aisles by two rows of columns, the middle of which was 9.00 meters wide and the side aisles 4.50 meters. To the east, the building is closed off by a semicircular apse into which a priest's bench of the same type is inserted. The six-sided outer cladding of the apse consists of considerably smaller cuboids and is also much less precise than the other large cuboid masonry of the church. From this it can be concluded that this outer shell was built later, certainly in Armenian times, possibly to secure the now dilapidated masonry from collapse.

Inside the apse, the chancel is in front of the width of the central nave. The excavators uncovered the remains of mosaics on the floor, which, similar to the Byzantine mosaics of the 5th century, were composed of white, black, red and yellow stones. They showed pictures of plants and animals, including a lion, a leopard and a buck, in a frame with geometric patterns. This includes writing fields in which, in addition to a Bible verse, the founder with the name Theognost is mentioned. Although no historical personality is known by this name , Herzfeld reads three letters at the edge of the Tabula ansata as the year 741 of the Seleucid era , which corresponds to the year 429 of the Christian era. In the area surrounding the chancel, further geometric ornaments in opus sectile technique came to light. A choir screen, fragments of which were found, separated the sanctuary from the believers in the main room. The back wall of the apse has dowel holes, which suggests cladding with colored marble slabs. On a far above Sima lying Apsiskalotte on. It was closed on both sides by two identical capitals , the north of which can still be seen in situ , while the other was found in the rubble. Above acanthus leaves in the lower part, they show ram's heads at the corners, with peacocks turning their wheels in between. To the right and left of the chancel there were two pastophoria that had the width of the aisles. They were connected to both the ships and the choir through doors.

Church above the cistern

The church above the cistern was a little south of the cathedral. Guyer and Herzfeld already report that apart from the cistern, only the apse was preserved, while there were no remains of the walls. With the construction of the thoroughfare to Erdemli at the end of the 20th century, it has completely disappeared. The apse was semicircular and had three arched windows. Underneath was a roughly rectangular part of the cistern 3 × 4 meters with rounded corners in the east. The main part was west of it and was 9.00 meters long and 7.50 meters wide in the east, it narrowed to the west to about 6.75 meters. It could have matched the ship above. It was divided into two naves from west to east by a row of pillars, the pillars being connected to the longitudinal walls by arches that supported the floor of the church. Another water tank was south of it. It was about the same length, but less than half as wide, and also covered by transverse arches. Since no ornamentation has been preserved, the building can hardly be dated.

Transept Basilica

At the eastern end of Via Sacra, outside the walled city area, is the transept basilica. Like almost all Cilician churches, it is oriented to the east and has dimensions of around 58.50 meters in length with a width of 18 meters in the main part, in the area of the ancillary rooms behind the apse the building is widened by a few meters. The western, 13.35 meter long part of the structure, which they call “Basilica No. 1 ”, Gertrude Bell believed in 1905 to be a monastery. During his excavations, Herzfeld was able to identify it as an atrium with an inner courtyard surrounded by columns on three sides and directly connected to the narthex of the church in the east. There was a door on each of the three outer sides, in the corners of the west wall there were two square rooms. It can no longer be determined whether they formed part of the atrium or were expanded like a tower. The narthex, which is only 4.70 meters deep, opened through three arches in the east. Beam holes and the approach of a staircase at the north end indicate an upper floor. From there one entered the three aisles of the Naos through three gates. As usual, the central nave was about twice the width of the side aisles, they were separated by rows of arches, each supported by seven columns and a pillar to the east. Two entrances as well as a triple and three double windows can still be seen in the south wall; the same arrangement can be assumed for the north wall.

The end pillars of the rows of columns stood 6.70 meters in front of the apse and were connected to the side walls by arches. This created a kind of transept, which Guyer led to the name "transept basilica extra muros". There were also connecting arches towards the apse, so that the choir was created in the extension of the central nave. It was separated from the side wings of the transept, i.e. the extensions of the side aisles, as well as from the central nave by barriers. Only a fragment of the side barriers has survived, showing a cross. From the barriers to the church interior, two marble blocks were still in situ during Herzfeld's excavations. On the side facing the community, they had a niche and profiles as the upper end. A cross could be seen in the right niche, the left showed a relief of the Lamb of God between two columns and a pediment and a Greek inscription below the profile. The excavators consider the blocks to be parts of martyrs' graves due to the sepulkral character of the inscription. There was a free passage between the blocks. Two other stone blocks with crosses and depictions of birds that were found in the rubble belonged to this or to a door in the side choir screen.

The chancel is adjoined to the east by the outside and inside semicircular apse, the diameter of which corresponds approximately to the width of the central nave. Today only fragments of it stand upright, Herzfeld and Guyer could still see three arched windows separated by pillars that illuminated the interior. To the right and left of the apse are the two spacious pastophoria, which tower above the church both in width and in length. They were closed off to the east by smaller apses, which were walled in a massive rectangular shape on the outside. The originally open space, paved with stone tiles, behind the main apse and between the pastophoria was enclosed with a wall in small pieces in Armenian times. Due to the design and stylistic characteristics, which point to influences from the East (Syria, Antioch ) as well as from Byzantium, Guyer dates the church to the late 6th century.

To the northeast of the basilica began with a tetrapylon the Via Sacra of Korykos, which led past sarcophagi and other churches to the west. Only one corner pillar has survived from this tetrapylon. From its structure it can be concluded that the building had four wide, open arches on its sides. The roof was supported by a circular cornice on the inside and a square cornice on the outside. There is no clarity about its construction, Guyer suggests a conical or dome-shaped wooden roof. As for the church, he considers the late 6th century to be the likely time of origin. To the south of the church is a cistern made of large blocks with gutters on the roof.

Holy Sepulcher

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher, known by Bell as “Basilica No. 2 ”, stands about 250 meters west of the transept basilica also on the holy road. It is noteworthy for several reasons. Firstly, at almost 80 × 30 meters, it is the largest of the churches in Korykos, and secondly, its structure is fundamentally different from that of the other church buildings. The reason for this is an older, square building in the center of the building, which Guyer and Herzfeld call Martyrion and after which they chose the name “Church of the Holy Sepulcher extra muros”. They take the substructures of two sarcophagi that they found there as evidence that the room was dedicated to the memory of two martyrs. The walls of the sanctuary with inner dimensions of 12 × 12 meters consisted of large cuboids, the dowel holes of which testify to a rich marble incrustation . The walls were pierced by arched entrances on all sides. The corner pillars with Corinthian capitals and approaches to the arches have been preserved in parts . To the west of the square, pillars appeared in a semicircle in front of the arch. Since a semicircular platform was also uncovered in the east, the excavators conclude that all sides were enclosed by apse-like porches. Fragments of a semicircle segment that were found to the east show that originally there was a closed apse, which initially also fulfilled this function for the church that was built later. One can only speculate about the upper end of this central building.

The actual basilica was later built around this space. Similar to the transept basilica, the western part of the building consists of an atrium that is 27 meters wide and 30.50 meters long. Central doors through the three outer walls were used for access. Like the doors of the church, they had a canopy. This consisted of two consoles with profiles on the sides and an acanthus leaf on the front, on which a barrel vault lay 1.35 meters deep , which was profiled like a sima at the front . These canopies have been preserved several times throughout the building. Nothing of the porticoed halls of the courtyard has survived, but from templates on the wall to the church part, conclusions can be drawn about their location on the north and south sides and probably also in the west. Instead, in the east, the narthex opened up to the courtyard through five column-supported round arches and two arches to the colonnades. The narthex itself was 4.70 meters deep and had an apse set into the wall in the south, while the remains of a staircase leading to the upper floor can be seen in the north. Its location can be recognized by the bar holes in the naos wall. On a pillar still standing on this wall, arches can be seen, which mean that there was a passage from this upper floor to the galleries of the main room.

From the narthex, three gates led into the interior of the church, the central one being larger than the others. Because the Martyrion is integrated into the overall plan, the gates do not lead into the usual three lengthways aisles, but into an approximately square room measuring 27 × 26 meters, with the Martyrion in the eastern center. Its west wall continued in the direction of the outer walls over a row of arches, so that in the west a room was created that was transverse to the church axis and was divided into two naves by a north / south row of columns. To the north and south of the sanctuary, two shorter aisles were built. In the west of the two transepts, the excavators uncovered a colored circle on the floor, executed in opus sectile technique, which was bordered by a square standing over a corner. In the next aisle, there was a radial pattern that corresponded to the western semicircular bulge of the central sanctuary. The eastern apse of this tomb also served as the main apse of the church when the church was built, making the Martyrion the church's choir. In the north wall, Herzfeld and Guyer were still able to trace the distribution of doors and windows. One door each, with a canopy like the atrium doors, led from the outside into the west transept and into the nave, the second transept had four windows separated by pillars, and the nave had two double windows. To the right and left of the apse were the two pastophoria, which were accessible through doors from both the chancel and the aisles. Similar to the transept basilica, they had an apse carved into the wall with a small window in the east. To the side of the pastophoria there were two long rectangular rooms, through which the outer floor plan of the entire building becomes a closed rectangle. Their function is unclear.

In a later construction phase, the choir was considerably enlarged by moving the apse, which directly adjoined the central square, further to the east. The space between pastophoria, originally open to the outside, was roofed over and a new main apse was added to the east. It is semicircular and has two arched windows that are separated by a pillar. One of the Corinthian apse capitals is preserved on the south corner, it shows stylistic similarities with the capitals of the martyrdom pillars. The outside of the back wall is aligned with the ends of the pastophoria. The brick wall technique allows the conclusion that the reconstruction took place not long after the church was built. The later construction clearly follows from joints in the east wall, where the apse abuts the pastophoria. A window from the southern adjoining room to the chancel, which only makes sense if it was previously in the open, is evidence of the subsequent renovation. Probably at the same time as this renovation, a cistern of roughly the same size was built under the chancel. The lower parts of it are carved into the adjacent rock and plastered. The ceiling formed a barrel vault. The excavators found an entry shaft in the southern Pastophorion, in the southern outer wall of the adjoining room there a water pipe with an unclear function was laid. The archaeologists consider a connection with possibly medicinal water and associated bathing rites in the elongated adjoining rooms to be possible. Probably at the same time, the pastophoria were given an upper floor. A corridor that connected these upper floors can still be seen today.

Herzfeld and Guyer dated the central grave space to the beginning of the 6th century through comparisons with other grave structures and through the stylistic classification of capitals. For the construction of the basilica they give the time around 550 after comparing them with eastern, Mesopotamian grave churches. Another renovation, in which a massive wall with only one door was drawn in between the choir and martyrion, was not carried out until the Armenian period, as evidenced by the small-scale masonry and the use of numerous Byzantine capitals as spoilage.

Monastery church

Another 300 meters further west, where the Via Sacra turns south towards the city gate, are the ruins of the monastery church, at Bell under “Basilica No. 3 "treated. It is a complex of several sacred buildings with seven apses that were built at different times. Guyer refers to these from north to south as A – G. The oldest are the two outer ones, A and G. They belonged to two single-nave chapels, of which only little has been preserved and the extent of which to the west can no longer be determined. A basilica was added to A from the north, the main apse of which is C, which was flanked by two side rooms. In addition - due to a slight shift in the axis, probably a little later - two aisles were built, and the side rooms were replaced by apses B and D. The dividing arches rested on pillars, of which some bases were found during the excavations. In the row of arches between the central nave and the southern aisle, remains of the floor using the Opus-sectile technique came to light. The remains of a choir screen could be exposed towards the apse. To the west of the ships was a narthex with three doors leading into it. A row of arcades led to a longer exonarthex, which also served as an anteroom for other buildings. The excavators assume that this basilica was built in the 7th century.

The following combination of vestibules DEF is a little younger. Its large central apse E has a horseshoe shape and is broken through by a window of the same type. In front of it lay the roughly square choir room and, separated by a row of arches, another square nave. The choir is connected to the side chapels D and F by two arches each, separated by a square pillar. The southern side room F does not have a rectangular, but a triangular floor plan, probably because of the Via Sacra that leads directly past it. The simple nature of the pillar capitals and the cornices of the apses point to a development in the late Byzantine, perhaps also in the Armenian period. The buildings to the west of it, which probably also served as residential buildings, probably date from the same period, which is why the entire complex may represent a monastery.

Burial church

About 1.6 kilometers east of the country castle are the remains of a burial chapel between the beach and the modern road. It was probably single-aisled with dimensions of 16 × 9.5 meters. Only parts of the apse, where the beginning of an arched window can be seen in the southern part, and sparse wall remains are preserved. From the foundations at the west end it can be concluded that it had a narthex, presumably with an open arch as the western entrance and a door to the naos. The floor was paved with limestone slabs. The walls consisted of small-format cuboids, while the apse dome consisted of larger blocks. Remains of plaster and beam holes can be seen on the north wall. On the south-west corner, the church is built over a barrel-vaulted hypogeum .

Armenian and medieval buildings

Great Armenian Church

Between the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the Monastery Church, a little south of the holy road, the ruins of another church stand. Only the eastern parts of it, i.e. the apses and choir rooms, have survived. At Bell it is called “Basilica No. 4 ”, Guyer and Herzfeld discuss it under“ Great Armenian Church ”. In the middle stands the remainder of the 6.20 meter diameter main apse with a round arched window and two side doors. On the right and left are the smaller side apses with a diameter of around 2.5 meters. Nothing is known about the length of the aisles, which certainly corresponded in width to the three apses, as there are no remains of the western walls. For the supports of the dividing arches between the naves, masonry pillars can be assumed, since at least fragments of the columns must have been preserved. Remnants of the wall that run parallel to the longitudinal walls to the north and south are what Guyer considers to be parts of side chapels. In the east of the apses, the remains of another wall complete the construction. This was connected to the main apse by two arches and also had two apses with a diameter of about 3.30 meters, which stood symmetrically in the gaps between the church apses. The resulting room had an upper floor, which can be recognized by the beam holes. One can only speculate about its function.

The walls consist of the small, roughly trimmed blocks typical of Armenian architecture. A remarkable lack of ornamentation can be seen throughout the building. There are no capitals, there are no cornices on the apses, the walls merge seamlessly into the domes. The apse arch rests solely on very simple transom plates . According to this simple, unadorned construction technique, the building is dated to the 13th century.

To the southwest of the churches in question, inside and directly adjacent to the city wall, there are the sparse remains of two other church buildings. They were probably basilicas in a very simple technique, so that they can also be dated to the time of the Armenian rule.

Country castle

In 1099 the Byzantine naval commander built a fortification on behalf of Emperor Alexios I on the headland, which in Roman times formed the ancient center of the city with the forum. Together with Camardesium Castle, which was built at the same time in Seleukia on Kalykadnos , about 25 kilometers southwest, it was supposed to secure the empire's sea route to Cyprus and thus to the Holy Land. After the Armenians took over rule in Korykos in the 12th century and the Kingdom of Cyprus in the 14th century, the fortress was expanded and strengthened several times. It consists of an irregularly shaped double wall ring in which numerous spoils of Roman buildings are built. In the south and west the structure borders directly on the Mediterranean Sea, in the north it was protected by swampy terrain, so that the strongest fortifications were on the east side. Inside there are farm buildings and the ruins of three churches from probably Armenian times. In 1448 the city and castle were conquered by the Karamanids and a little later by the Ottomans.

Seeburg

The island fortress is located on an offshore island about 600 meters southwest of the country castle. The remains of a pier can be seen in front of the country castle, which may have connected the castles. The British Admiral Beaufort reported at the beginning of the 19th century that there was a platform, perhaps for a lighthouse, which formed the end of the pier about 100 meters from the land fortress. The walls of the castle are polygonal, the south and west walls are rectangular to each other and the north-eastern curtains connected the ends in a wide arch. Eight towers or bastions are integrated into the walls . They have partly a square and partly a round or semicircular floor plan. Their total length is 192 meters. The entrance was in one of the semicircular north towers. The partially restored donjon still stands at the southeast corner . Langlois reports on two inscriptions on this tower that have been lost today, one of which stated that the Armenian King Leon II was the builder. Contrary to the opinion of Guyer and Herzfeld, Hellenkemper assumes that there was no previous Byzantine building, and takes Leon's reign (1187–1219) as the construction date. Few building remains can be seen inside. There was a small, single-nave chapel next to a battlement in the west and a cistern.

A legend has grown up around the island castle, to which it owes the current name of the Mädchenburg ( Turkish Kız Kalesi ). Then a princess was banished to the island because an oracle had predicted her death by a snakebite. Nevertheless, the snake overtook them over a fruit basket.

Necropolis

The numerous tombs of Korykos are divided into three sections, which Alois Machatschek, who published a detailed description of the necropolis in the 1960s, designated with "N1", "N2" and "N3". The necropolis N1 begins northwest of the country castle, today on the opposite side of the street, and pulls up a terraced slope rising to the northwest on both sides of the city wall. In the lower area there are 20–30 rock graves, besides there are a large number of partly fixed sarcophagi and above all several hundred chamosories. In the latter case, the burial space carved into the rock is occasionally enlarged and equipped with up to three arcosol niches . To the north of N1 runs a valley inland, into which the second necropolis N2 extends up to 500 meters. It also consists for the most part of sarcophagi and chamosoria as well as 60–70 rock graves. Their arrangement on the lower rock faces of the valley prompted Langlois to use the flowery term "natural columbarium ". The necropolis N3 adjoins it in the southeast. Their graves are located on both sides of the Via Sacra, from the monastery church about 200 meters to the Holy Sepulcher. Here sarcophagi are to be found almost exclusively, there are isolated chamosories at the edges.

The use of the necropolis extended over seven centuries, roughly from the turn of the ages to the 7th century. While sarcophagi were common over the entire period, rock tombs were mainly created in the 1st and 2nd centuries, i.e. in pre-Christian times. Burial houses were in use in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. Of the latter, only one is preserved in Korykos in polygonal masonry on the northeast slope of the necropolis N2. All the others were presumably removed and reused when the country castle was built, as they were ideally suited to prefabricated stone blocks. Rock graves and burial houses date from pagan times, while in the Christian era only burials took place in sarcophagi or chamosoria. Sarcophagi from pre-Roman times could not be found - as in the wider area - they did not appear until the 1st century at the earliest. However, there is no evidence of a more precise dating of most of these graves. Many of the grave sites have been used several times, which can be recognized by subsequent and additional inscriptions.

Sarcophagi

construction

In the case of sarcophagus-like tombs, a distinction can be made between free-standing sarcophagi with and without substructure, fixed sarcophagi and chamosoria. With the sarcophagi, free-standing as well as stationary, the external dimensions correspond approximately to the ratio of 2: 1: 1 (length: width: height). The length varies from 2.10 to 2.70, the width from 0.90 to 1.40 and the height from 0.90 to 1.50 meters, although those without a substructure are slightly smaller. The base occasionally contains additional cavities, which most likely represented further burial chambers. The predominantly simple cover has the shape of a gable roof with a slope of usually less than 30 °, in extreme cases up to 45 °. The weight of the lids is two to three tons in the larger specimens, which also means protection against grave robbery. The dimensions of the chamosoria are slightly smaller than those of the sarcophagi, they are 1.50 to 1.85 meters long and 0.45 to 0.65 meters wide. The grave rooms are about 0.60 to 1.00 meters deep in the surrounding rock and expand downwards in both directions by about 20 centimeters, which saves material and costs in terms of the size of the lid. In some cases the slope is larger, so that there is room for two burials. Occasionally, smaller chambers with a length of 80 to 90 centimeters appear, which were obviously intended for children. In a few cases, the burial space in necropolis N1 has been enlarged to a burial chamber, similar to those of the rock tombs, in which arkosol-like niches for three buried persons are incorporated.

ornamentation

Most of the sarcophagi and chamosoria are quite simple. Basically only three sides have been processed, the reverse side is only roughly smoothed. The three visible sides are delimited with profiles at the top and bottom. Most of the graves show inscriptions, often in a tabula ansata , only symbols on the lid. Among them were originally pagan symbols such as leaves and grapes, which were also used later, as well as Christian crosses and some Jewish seven-armed candlesticks . On some graves, motifs of all faiths are represented, which indicates on the one hand a long useful life and on the other hand a peaceful coexistence of the religions.

Four garland sarcophagi and one erotic sarcophagus are better equipped, all in necropolis N1. Due to their similarity, the garlands probably come from the same workshop. There are two on the long side and one on the narrow side decorated with fruits, leaves and grapes. They hang over bucrania and gorgons' heads can be seen below . The erotic sarcophagus also in N1 shows a scene with several erotes around a central crater . They drink, dance and make music, one of them is drunk, on the side is a Pan with Syrinx . Also noteworthy are two lids, one near the monastery church with the badly damaged busts of a married couple and in N1 one with the also not well-preserved sculpture of a reclining lion, a motif that also occurs in Tekkadın , for example .

Rock tombs

construction

The rock chamber tombs in necropolises N1 and N2 have an entrance in the middle of the facade with a width between 60 and 70 centimeters and a height of 1.00 to 1.20 meters. The door could be locked with stone blocks weighing up to 700 kilograms, the blocks were often found in the area. The door threshold is level with the floor of the burial chamber. The chamber itself is generally square with sides between two and three meters and has a flat, roughly head-high ceiling. Inside the door wall is kept free, on the other sides arcosolic niches are usually worked into the walls 60–80 centimeters above the floor, with a length of 1.80–2.10 and a depth of 0.80–1.00 meters. An exception are some chambers in which the dead were buried on surrounding benches. The length dimensions of these are slightly smaller. In both cases, increased head rests can be observed. In N2, the majority of the graves have two grave niches one above the other, occasionally also deeper niches, which, separated by a ledge, could accommodate two people. Apart from a few small niches for the acceptance of offerings, there is no other interior.

Since the graves had to be carved out of the existing sloping terrain, there was usually a courtyard bordered on three sides. In addition to its symbolic meaning as a foyer for the buried, it was certainly also the place for the funeral meal and other rites. This is indicated by benches in some graves, as well as traces of roofing.

Facades

The facades of the graves are smoothed about 3–4 meters wide. Their main design element is the doors, which are located in a generally rectangular, in N2 predominantly semicircular niche. The niche with beveled edges was used to accommodate the locking stones. Elements that imitate architecture, as in others, for example Lycian rock tombs, are not present. Similar to the sarcophagi, there are only exceptional cases of pictorial representations such as portrait busts of the deceased. In addition to the inscriptions, most of the ornamentation is represented by symbols, which here are predominantly of pagan origin. These mainly include altars in relief, above which a small semicircular niche was used to hold lamps or offerings. The height of the lamp niches varies widely from 0.10 to 1.00 meters. Further symbols are grapes, ivy tendrils, baskets, wreaths, torches and a pair of hands that are supposed to have a disaster-warding function. Various graves also show Christian crosses when they were later used.

Burial house

The only preserved burial house of Korykos is at the eastern end of the necropolis N2. The lower part is carved into the surrounding rock like a rock grave with a surrounding bench. The upper part of the building is made of embossed polygonal masonry . The stones have dimensions of between 60 and 80 centimeters with a similar thickness. An inscription from Christian times is carved on the lintel, stating that Paul and his wife Georgia were buried. The relief of a grave altar on the eastern side wall, however, as well as the old wall technology, shows that the building dates from earlier times.

Inscriptions

The more than 700 inscriptions of the graves of Korykos, including more than 500 from Christian times, are very well documented, especially by Keil and Wilhelm. Heberdey and Wilhelm described them as "unbearably boring" because, in addition to the designation σωματοθήκη somatotheke or just θήκη theke for short (Greek for “tomb”), they mostly only reflect the names and professions of the buried. They are almost exclusively in Greek and are mostly badly weathered and difficult to read. For some, curses against desecration of the grave with threats of expected fines are given. In no case do they contain dates and only rarely do they contain the names of rulers or other information necessary for dating.

However, by naming them they give a good picture of the population structure of the place. As in neighboring Korasion to the west , there were numerous oil and wine traders, as well as textile processors, as well as dye works and cleaning companies. Money changers were organized in a professional association. The city's port was also important as a trading center. Shipowners, sail repairers, sailors, dock workers and ship carpenters were represented among the relevant professions. In another association, the manufacturers of lines for the manufacture of sails were united.

Warrior relief

About 100 meters northwest of the country castle, on the opposite side of the modern road, the rock relief of a warrior can be seen near the graves there. The figure shown in the front is 1.80 meters tall. The legs are wide apart, the shoulders are block-like wide. His right hand holds a lance, and his left hand holds a sword hanging on his belt. The soldier is dressed in a short chiton , the folds of which converge diagonally up to the belt. Serra Durugönül suggests, based on stylistic comparisons with the other rock reliefs she examined in the Rough Cilicia, that the representation be dated to the 1st century AD.

Famous citizens

- Procopius (around 326–366), Roman counter-emperor

- Hethum of Korykos (1230/45 – after 1308), Armenian historian.

- Oshin of Korykos , regent of Lesser Armenia (1320–1329)

literature

- Rudolf Heberdey , Adolf Wilhelm : Journeys in Kilikien 1891-1892 (= memoranda of the Academy of Sciences. Volume 44, 6). Vienna 1896, pp. 67-70 ( digitized version ).

- Josef Keil , Adolf Wilhelm: Monuments from the rough Cilicia. (= Monumenta Asiae Minoris Antiqua . Volume 3). Manchester 1931, pp. 122-213.

- Ernst Herzfeld ; Samuel Guyer : Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. (= Monumenta Asiae Minoris Antiqua. Volume 2). Manchester 1930.

- Alois Machatschek : The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia (= memoranda of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Volume 96; = Tituli Asiae minoris supplementary volumes. Volume 2). Böhlau, Vienna 1967.

- Theodora Stillwell MacKay: Korykos Rough Cilicia, Turkey . In: Richard Stillwell et al. a. (Ed.): The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976, ISBN 0-691-03542-3 .

- Hansgerd Hellenkemper : Crusader castles in the county of Edessa and in the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Studies on the historical settlement geography of Southeast Asia Minor (= Geographica historica. Volume 1). Habelt, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7749-1205-X , pp. 242-249.

- Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien and Isaurien (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini . Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , pp. 315-320.

- Stephen Hill: The Early Byzantine Churches of Cilicia and Isauria . (= Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Monographs Volume 1), University of Birmingham 1996 ISBN 0860786072 , pp. 115-147 fig. 17-23 pl. 33-59

Web links

- Peter Pilhofer : Korykos

- Kizkalesi Castle ( Memento from January 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (German)

- Korykos and Kizkalesi (English)

References and comments

- ↑ Ancient City of Korykos

- ↑ Kai Trampedach : Temple and Great Power: Olba in Hellenistic times. In: Éric Jean, Ali M. Dinçol, Serra Durugönül (eds.): La Cilicie. Espaces et pouvoirs locaux (2e millénaire av. J.-C. - 4e siècle ap. J.-C.). = Cilicia. Mekânlar ve yerel Güçler (M.Ö. 2. binyıl - MS 4. Yüzyıl) (= Varia Anatolica. Volume 13). Institut français d'études anatoliennes d'Istanbul et al., Beyoglu-Istanbul et al. 2001, ISBN 2-906053-64-3 , p. 270.

- ↑ Serra Durugönül: Towers and Settlements in Rough Cilicia. (= Asia Minor Studies. Volume 28). Rudolf Habelt, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-7749-2840-1 , p. 94.

- ↑ Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien und Isaurien (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , p. 315.

- ^ Strabons Geographika, Book XIV, p. 105

- ↑ Serra Durugönül: The rock reliefs in the Rough Kilikien . (= BAR International Series. 511). BAR, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-86954-652-7 , p. 58.

- ↑ Serra Durugönül: The rock reliefs in the Rough Kilikien . (= BAR International Series. 511). BAR, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-86954-652-7 , pp. 58-64.

- ↑ Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien und Isaurien (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , pp. 128–130.

- ↑ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Castles of the Crusader period in the county of Edessa and in the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Studies on the historical settlement geography of Southeast Asia Minor (Geographica historica. Volume 1) . Habelt, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7749-1205-X , p. 242.

- Jump up ↑ Sir Francis Beaufort: Karamania, Or, A Brief Description of the South Coast of Asia-Minor and of the Remains of Antiquity With Plans, Views, & c. Collected During a Survey of that Coast, Under the Orders of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, in the Years 1811 & 1812 . R. Hunter, (successor to Mr. Johnson,), 1817, p. 232-239 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Léon de Laborde, Alexandre de Laborde: Voyage de l'Asie mineure. Didot, Paris 1838, pp. 132-134 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Victor Langlois: Voyage dans la Cilicie et dans les montagnes du Taurus exécuté pendant les années 1851-1853 ... B. Duprat, 1861, p. 193-219 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Louis Duchesne, Maxime Collignon: Sur un voyage archéologique en Asie Mineure In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 1, 1877, pp. 361-373 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Louis Duchesne: Les Nécropoles chrétiennes d'Isaurie In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 4. 1880, pp. 195-205 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ James Theodore Bent: A Journey in Cilicia Tracheia In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . 12 1891, pp. 206-224.

- ^ Edward L. Hicks: Inscriptions from Western Cilicia. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 12, 1891, pp. 225-273.

- ^ Rudolf Heberdey, Adolf Wilhelm: Journeys in Kilikien 1891-1892 (= memoranda of the Academy of Sciences. Volume 44, 6). Vienna 1896 pp. 67–70.

- ↑ Gertrude Bell: Notes on a Journey through Cilicia and Lycaonia. In: Revue archéologique . 4th series, volume 8, (Juillet-Décembre 1906) pp. 7-36.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld: A journey through western Kilikien In: Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen 1909/2 S. 25–34.

- ^ Roberto Paribeni, Pietro Romanelli: Studii e ricerche archeologiche nell'Anatolia meridionale In: Monumenti Antichi. Volume 23, 1914, pp. 1-274.

- ^ Josef Keil, Adolf Wilhelm: Monuments from the rough Cilicia. (= MAMA 3), Manchester 1931, p. 192, No. 122-213

- ^ Alois Machatschek: The necropolises and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia, Vienna 1967.

- ↑ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Castles of the Crusader period in the county of Edessa and in the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Studies on the historical settlement geography of Southeast Asia Minor (= Geographica historica. Volume 1). Habelt, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7749-1205-X , pp. 242-249.

- ↑ Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien und Isaurien (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , pp. 315-320.

- ↑ Hansgerd Hellenkemper, Friedrich Hild: New research in Kilikien . (= Publications of the Commission for the Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 4). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1986, ISBN 3-7001-0771-4 .

- ^ Robert L. Vann: A Survey of Ancient Harbors in Rough Cilicia: The 1995 Season at Korykos In: Araştırma sonuçları toplantısı. Volume 14, Ankara 1996, Eski Eserler ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü pp. 259-271.

- ↑ KORYKOS (Kızkalesi) Arkeolojik Yüzey Araştırması ( Memento of the original from April 11, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Livy, Ab Urbe condita 33, 20 .

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia . Böhlau, Vienna 1967, p. 13 f.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, p. 91.

- ↑ Cicero, ad Familiares 12, 13 .

- ^ Livy, Ab Urbe condita 33, 20 .

- ^ Pliny, Naturalis historia 5, 92 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien und Isaurien. (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , pp. 315-320.

- ^ Josef Keil, Adolf Wilhelm: Monuments from the rough Cilicia. Manchester 1931, pp. 122-129.

- ^ Sviatoslav Dmitriev: City Government in Hellenistic and Roman Asia Minor . Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-534690-4 , pp. 213 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ According to Herzfeld, p. 92, the castle was built by Eustathios in 1099, but this is corrected by Hild / Hellenkemper p. 319.

- ^ Victor Langlois: Voyage dans la Cilicie et dans les montagnes du Taurus: exécuté pendant les années 1851–1853 ... B. Duprat, Paris, 1861, p. 215 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Castles of the Crusader period in the county of Edessa and in the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Studies on the historical settlement geography of Southeast Asia Minor. (= Geographica historica. Volume 1). Habelt, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7749-1205-X , pp. 244-245.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, p. 93.

- ↑ Oppian, Halieutika 3,205-210.

- ^ The Luwian Population Groups of Lycia and Cilicia Apera During the Hellenistic Period . S. 242 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Serra Durugönül: The rock reliefs in the Rough Kilikien. (= BAR International Series 511). BAR, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-86954-652-7 , pp. 142-143.

- ^ Margaret H. Williams: The Jewish Community of Corycus: Two More Inscriptions In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Volume 92, (1992) pp. 248-252.

- ^ Serra Durugönül, Ahmet Mörel: Evidence of Judaism in Rough Cilicia and its Associations with Paganism. In: Istanbul communications. 62, 2012, pp. 303-322.

- ^ Margaret Williams: Jews in a Graeco-Roman Environment . Volume 312 of Scientific Studies on the New Testament, Mohr Siebeck, 2013, ISBN 978-3-16-151901-7 , pp. 237-247.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, pp. 173-176.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, p. 91.

- ^ Robert L. Vann: A Survey of Ancient Harbors in Rough Cilicia: The 1995 Season at Korykos In: Araştırma sonuçları toplantısı, Volume 14. Ankara 1996 Eski Eserler ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü p. 264.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia . Böhlau, Vienna 1967, p. 21.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930 pp. 94-108.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, pp. 109-110.

- ↑ Gertrude Bell: Notes on a Journey through Cilicia and Lycaonia. In: Revue Archéologique. 4th series, volume 8, (Juillet-Décembre 1906) pp. 7-36.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, pp. 112-126.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, pp. 126-150.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, pp. 154-161.

- ↑ Stephen Hill: The Early Byzantine Churches of Cilicia and Isauria . (= Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Monographs Volume 1), University of Birmingham 1996 ISBN 0860786072 , pp. 143-144 fig. 17-23 pl. 53-54.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, pp. 150-154.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, p. 110.

- ↑ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Castles of the Crusader period in the county of Edessa and in the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Studies on the historical settlement geography of Southeast Asia Minor. (= Geographica historica. Volume 1). Habelt, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7749-1205-X , pp. 242-249.

- ↑ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Castles of the Crusader period in the county of Edessa and in the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Studies on the historical settlement geography of Southeast Asia Minor. (= Geographica historica. Volume 1). Habelt, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7749-1205-X , pp. 242-249.

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Samuel Guyer: Meriamlik and Korykos. Two Christian ruins in Rough Cilicia. Manchester 1930, p. 165.

- ↑ Marianne Mehling (Ed.): Knaurs Kulturführer in Farbe Turkey . Droemer-Knaur, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-426-26293-2 , p. 375.

- ↑ Keil / Wilhelm use A, B and C

- ^ Victor Langlois: Voyage dans la Cilicie et dans les montagnes du Taurus exécuté pendant les années 1851–1853 ... B. Duprat, Paris, 1861, p. 207 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 16, 21.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, p. 21.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, p. 65.

- ↑ Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien and Isaurien. (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini . Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , p. 317.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 46-48.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 34–43.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 23-24.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 38-40.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 49-52.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ Serra Durugönül: The rock reliefs in the Rough Kilikien . (= BAR International Series Volume 511). BAR, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-86954-652-7 , p. 112.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 52-54.

- ^ Josef Keil, Adolf Wilhelm: Monuments from the rough Cilicia. Manchester 1931, p. 192 no.648.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, pp. 65-67.

- ^ Josef Keil, Adolf Wilhelm: Monuments from the rough Cilicia. Manchester 1931, p. 192, nos. 122-213.

- ↑ Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien und Isaurien (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , p. 315.

- ^ Rudolf Heberdey, Adolf Wilhelm: Journeys in Kilikien 1891-1892 (= Denkschriften Wien 44/6). Vienna 1896, p. 50.

- ↑ Alois Machatschek: The necropolis and tombs in the area of Elaiussa Sebaste and Korykos in the rough Cilicia. Vienna 1967, p. 23.

- ↑ Friedrich Hild, Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Kilikien and Isaurien. (= Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Volume 5). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-7001-1811-2 , pp. 315-316.

- ↑ Serra Durugönül: The rock reliefs in the Rough Kilikien . (= BAR International Series 511). BAR, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-86954-652-7 , pp. 28, 100, 103.