Edward II (England)

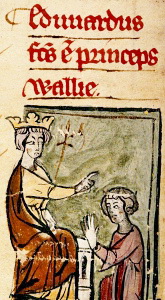

Edward II ( English Edward II, also Edward II of Carnarvon; born April 25, 1284 in Caernarvon , Wales ; † September 21, 1327 in Berkeley Castle , Gloucestershire ) was a King of England , Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine . He was the first heir to the throne to bear the title of Prince of Wales and was the first English monarch to be deposed since the Norman conquest in 1066 .

Origin and youth

origin

Edward II was the fourth son and youngest child of Edward I of England and his first wife Eleanor of Castile . He was believed to have been born in Caernarfon Castle , which is under construction . His father is said to have purposely arranged his birth in North Wales in order to strengthen English rule in Wales, which had recently been conquered by the birth of a prince in Wales (see Conquest of Wales by King Edward I ). Allegedly he is said to have promised the Welsh a ruler who was born in Wales and does not speak a word of English. As a result, Edward was made the first Prince of Wales at the age of 16. This was not claimed until the 16th century, but this version sounds plausible. Caernarfon Castle, the most magnificent of King Edward I's new castles in Wales, was to serve as the residence of the new Prince of Wales, but his son never returned as an adult.

Childhood and upbringing

Eduard was at least the 14th child of Queen Eleonore, but after the death of his older brother Alphonso in August 1284 he was the only surviving son. Although Edward was thus established as heir to the throne, his parents paid little attention to his upbringing, and nothing is known about the systematic upbringing and training of the heir to the throne. Between May 1286 and August 1289 his parents were in France. When his father was planning a new crusade in April 1290, in the event of Eduard's death he also granted all his daughters the right to succeed him as king. Edward's mother Eleanor died on November 28, 1290, from whom he inherited the counties of Ponthieu and Montreuil in France. In June 1291 his grandmother Eleanor of Provence died . His numerous sisters were married or entered monasteries. From 1290 at the latest, Dominican monks belonged to his household, and Eduard maintained a close relationship with the order throughout his life. In 1290 his mother instructed her scribe Philip to teach Eduard. Edward's mother tongue was French, which he could also read, and he also understood English like his father. It is not known whether he was also able to write. From 1295, perhaps even from 1293, until his death in April 1303, the knight Gui de Ferre from Gascony was responsible for Edward's knightly and military training. Although the heir to the throne was considered strong, athletic and a good rider as a youth, he is not known to have participated in a tournament .

Marriage plans and engagements

His father planned to marry his son to the Scottish heir to the throne Margarete , the Maid of Norway . The marriage was contractually regulated in the Birgham Agreement in July 1290, but the young bride died that same year while crossing to Scotland. After the beginning of the Franco-English War in 1294, his father wanted to marry him to a daughter of Count Guido of Flanders in order to strengthen the alliance between Flanders and England. According to the armistice negotiations in 1298, this agreement was canceled by Pope Boniface VIII . In the Treaty of Montreuil in June 1299, Eduard's engagement to the French princess Isabelle de France was decided, which should end the war between England and France. After the Treaty of Paris of 1303 , which finally ended the war with France, Eduard and Isabelle were officially engaged.

Role as heir to the throne and first Prince of Wales

During the Franco-English War from 1294 to 1303 Eduard was nominally Commander-in-Chief of English troops in 1296, which were supposed to fend off a feared French invasion of England. During the political crisis in the summer of 1297, the leading magnates swore allegiance to him on July 14, 1297 in the presence of his father in Westminster . He was then the official regent of England between August 22, 1297 and March 14, 1298 when his father was in Flanders. On October 10, 1297 he officially offered a pardon to Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk , Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford and other opposition magnates and confirmed the Confirmatio Cartarum , a revised version of the Magna Carta , which resolved the crisis has been. During the first Scottish War of Independence he gained his first military experience during the siege of Caerlaverock Castle in July 1300. During Parliament in Lincoln , Edward was named the first English Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester on February 7, 1301 . The king wanted to consolidate the English rule over the conquered Wales, at the same time he gave his son his own rule with his own income. The young Prince of Wales visited Wales in April and May 1301, where he received the homage of his subjects; this was his only visit to Wales until his escape in October 1326.

During the campaign to Scotland in the summer and autumn of 1301, Eduard commanded part of the English army under the command of his father without much success. He presided over a council of magnates for the first time in March 1302 in his father's absence, and was called to Parliament as Earl of Chester in July and October. In autumn 1303 he again took part in a campaign to Scotland, where he stayed until the conquest of Stirling Castle in July 1304. On June 14, 1305, there was a falling out between the king and the heir to the throne at Midhurst , Sussex . Edward had gotten into an argument with his father's Lord High Treasurer , Walter Langton . The reason for this is unknown; it was probably due to the high costs of the heir's own household. The father took sides with his powerful but unpopular confidante and banished his son from his court. He probably wanted to separate Eduard from some of his friends, whose influence he disapproved of. One of them was the young Piers Gaveston from France , whom the king himself had accepted into the household of the heir to the throne in 1300. Gaveston had become the heir apparent's closest friend and had a great influence on him. Even contemporaries suspected that there was also a sexual relationship between the two. Some modern historians also believe that there was a homosexual relationship between them, but this cannot be proven and is still controversial today. Only on the name day of Eduard the Confessor on October 13, 1305 did a reconciliation between father and son take place, but the trust between the two was badly damaged. On April 7, 1306, the heir to the throne was made Duke of Aquitaine , and on May 22, he and 266 other young men were made Knight of the Bath in a solemn ceremony in Westminster . His father reassigned him to command an English army with which Edward invaded Scotland in August 1306, but his father angrily recalled him because of the looting and excesses of the English army. Gaveston, who, contrary to the king's orders, did not take part in the campaign together with other young knights, incurred the king's anger again and had to go into exile in February 1307.

First years of reign as a king

Coronation and wedding

King Edward I died in July 1307 during another campaign against Scotland in northern England. On July 20th, the English magnates paid homage to his son as their new king. One of the first measures of Edward II. As king was the retrieval of Gaveston, whom he in on August 6 Dumfries for Earl of Cornwall rose. He then returned to England and held a parliamentary assembly in Northampton on October 13th to organize his father's funeral and his own wedding and coronation. In addition, he took revenge on Walter Langton, whom he deposed and imprisoned. The new Lord High Treasurer was Walter Reynolds , the previous administrator of his household. On November 1, 1307, Gaveston married Edward's niece Margaret de Clare , a sister of the powerful Earl of Gloucester . Eduard named Gaveston his regent before sailing to France on January 22, 1308. On January 25, the wedding of Edward II and Isabelle de France, which had been postponed several times , took place in Boulogne in the presence of King Philip IV and numerous nobles. On January 31, he paid homage to his father-in-law for his possessions in France .

Beginning of the aristocratic opposition

He returned to Dover with his wife on February 7, 1308 , and on February 25 the royal couple were crowned at Westminster Abbey . The splendid celebration was disrupted by the anger of the French visitors and the English barons over the favor and behavior of Gaveston. During their stay in France, a group of barons had already expressed their displeasure with the royal policy in the Boulogne Agreement . Their disappointment erupted on April 28 when, during a parliament in Westminster under the leadership of the Earl of Lincoln, they appeared before the king and declared that they owed obedience to the crown, but not necessarily to the person of the king, and called for Gaveston's banishment. In view of the closed aristocratic opposition, Edward II had no choice and on May 18 he agreed to his friend's exile. However, he circumvented the exile by making Gaveston Lieutenant of Ireland . To do this, he turned to the Pope with the request that Gaveston's exile be lifted. The provisional banishment initially led to a reconciliation between the king and the barons in Northampton in August. During parliament in April, the barons had submitted reform proposals to the king, which the king wanted to discuss. By the summer of 1309 he had succeeded in turning the mood against Gaveston. He returned to England and met Eduard on June 27, 1309 in Chester . At Parliament in Stamford in August 1309, the King approved the barons' reform proposals. Edward II, however, continued to favor Gaveston while, despite his promise, he did not implement the reform proposals. Then the remained Earls of Lancaster , Lincoln, Warwick , Arundel and Oxford a Council meeting in October in Oxford away. During the Parliament of Westminster in February 1310, the king finally had to bow to pressure from the barons who threatened his removal. He agreed to the appointment of a 21-member committee, the so-called Lords Ordainer, which should make concrete reform proposals by September 29, 1311.

While the Lords Ordainer were deliberating in London, the King called his army to Berwick on September 8th to secure his position in Scotland. The Earls of Lancaster, Pembroke , Hereford and Warwick stayed away from the call as they worked as Lords Ordainer on their reform proposals, and only sent a minimum bid. At the end of October 1310 Edward II reached Edinburgh , but while part of the army under Gaveston pushed further north, the king returned to Berwick in early November. There he stayed until the end of July 1311. With the death of the moderate Earl of Lincoln in February 1311, the leadership of the aristocratic opposition was passed on to his son-in-law Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, who was a cousin of the king and the richest magnate in England.

The ordinances

The Lords Ordainers finally laid down their work in 41 provisions, the so-called Ordinances , which comprised a wide range of reform proposals. You requested u. a. the approval of parliament for the granting of land donations and privileges as well as for the appointment of the highest civil servants and the strengthening of the treasury in relation to the royal budget. Ultimately, the barons demanded greater participation and, above all, the removal of the king's so-called bad advisors, especially Gaveston. The king initially refused to accept these proposals, as they clearly restricted his sovereignty and he opposed Gaveston's final banishment. Eventually he had to give in to pressure from the barons. On September 27, 1311 the ordinances were announced in London.

Gaveston conflict escalates

On October 12, the king turned to the Pope to have the ordinances annulled, and at the same time he was determined to lift Gaveston's exile. He met him at the latest on January 13, 1312 in Knaresborough , from where they traveled to York . This disregard for the ordinances led to an open conflict with the barons. Archbishop Robert Winchelsey of Canterbury called the prelates and magnates to deliberate on March 13 at St Paul's Cathedral in London. There the Earls of Pembroke and Surrey were assigned to take Gaveston prisoner. The King and Gaveston fled to Newcastle in mid-April and on to Scarborough in early May , where they parted. While the king was returning to York, Gaveston was besieged at Scarborough Castle and surrendered on May 19th. The Earl of Pembroke guaranteed his safety until further negotiations were concluded and had him taken to London. On the way, however, Gaveston came under the control of the Earl of Warwick, who took him to Warwick Castle and finally had him executed on June 19 after consulting the Earls of Lancaster, Hereford and Arundel.

The Earls of Pembroke and Surrey then rejoined the king. He was now determined to cancel the ordinances. At first, an open civil war loomed until the king summoned the barons to Westminster for further negotiations. Lengthy negotiations followed, until on December 20 the king agreed to grant the magnates involved the execution of Gaveston. In return, they submitted to him and gave him the jewels and jewelry they had taken from Gaveston, who was officially the royal chamberlain . It was not until two years later, on January 2, 1315, that the king had the remains of Gaveston finally buried in a solemn ceremony in the chapel of his favorite residence in Kings Langley .

War with Scotland and conflict with the Earl of Lancaster

Defeat in the war with Scotland

Despite this superficial reconciliation, the two parties continued to distrust each other. The implementation of the agreements was delayed and the parliaments of March 18 and July 8, 1313 ended with no concrete results. The king's position was strengthened by the death of Archbishop Winchelsey in May 1313 and the election of his confidante Walter Reynolds as his successor. From May 23 to July 16, 1313, the King and Queen made a state visit to Paris. Together with the French king, Edward II had taken the cross on June 6th in Notre-Dame Cathedral , and on July 2nd they were able to settle a number of points of conflict over the English king's possessions in south-west France in an agreement. The support of his father-in-law and the diplomatic efforts of the Pope led to a further agreement between King Edward II and the aristocratic opposition, which submitted to the king on October 14th. The king forgave them again and on November 28, 1313 received the approval of the barons for a new campaign to Scotland, which was to take place in June 1314. On December 12th the king traveled to Boulogne to meet King Philip IV in Montreuil and to obtain his approval for a pledge of the income from Aquitaine to the Pope. For this Edward II had received a large loan from the Pope, and on December 20th he returned to England. Although the question of ordinances had not yet been finally resolved, the king had successfully regained part of his sovereignty and strengthened his position. News of the Scots' capture of Roxburgh Castle and Edinburgh Castle now forced the king to act. The constable of Stirling Castle , the last remaining English-occupied castle in Scotland, had announced that he would have to surrender if the castle was not appalled by June 24th. This gave the English king the opportunity to face the Scottish army in an open field battle in front of the besieged castle. Lancaster, Warwick and other barons refused to take part again, but at the beginning of June the king was able to lead a vastly outnumbered army to Stirling. However, the king's weak military leadership resulted in the English suffering a decisive, humiliating defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn . Edward II himself fought valiantly, but eventually had to be led off the battlefield by Henry de Beaumont and others to avoid capture. He fled by ship to Berwick and on to York, where he convened a parliament in September. Faced with the defeat, he had to confirm the ordinances and replace his leading ministers.

During parliament in January and February 1315, the king had to make further concessions and ensure strict compliance with the ordinances. The Scots were now trying to take advantage of Bannockburn's victory. In May 1315 a Scottish army landed under Edward Bruce , the brother of the Scottish King, in Ireland to conquer the English territories there . In July 1315 the Scots besieged Carlisle Castle and the whole of northern England had to pay tributes to the Scottish king, which Edward II had to tacitly accept.

Failure of the Lancaster government

Edward II conferred with his leading magnates in Lincoln in late August and in Doncaster in mid-December 1315 . On January 27, 1316, the parliament met in Lincoln, which on February 17 appointed Lancaster chairman of the royal council to implement the ordinances and other reforms. However, given the crisis of the empire, triggered by the Scottish attacks, the poor financial situation and the famine , Lancaster could not achieve any quick success either, and in view of the continued opposition to the king he withdrew to his possessions in northern England at the end of April 1316. This led to further instability of the empire. The north of England continued to be subject to Scottish attacks, and both the King, Queen and Lancaster made their own candidates to succeed the late Bishop of Durham . The king sent a high-ranking embassy to the new Pope John XXII. to obtain his assistance against the Scots, to obtain financial concessions on account of his debts, and to be released from the oath of ordinances. On March 28, 1317, the Pope lent him the proceeds of the English Church tithing and on May 1 he ordered an armistice between England and Scotland, but he did not release the king from the ordinances. The Pope commissioned two cardinals to negotiate a lasting peace with Scotland, but in the end they had to mediate between the King and Lancaster. Both the King and Lancaster retained troops, ostensibly for a campaign to Scotland announced for September 1317. This did not take place, however, and when the king traveled from York to southern England in early October, his companions had to dissuade him from attacking Lancaster at Pontefract Castle .

Rise of the minions and further conflict with Lancaster

Lancaster's hatred of the king was heightened by the rise of a series of favorites to whom the king gave rich gifts. They included Roger Damory , Hugh de Audley , William Montagu , Hugh le Despenser the Elder and especially his son Hugh le Despenser the Younger. Damory and Audley had married two of the sisters and heiresses of the Earl of Gloucester, who had fallen at Bannockburn, and had come to great fortune. In addition, a number of barons, above all Pembroke, Hereford and Bartholomew de Badlesmere , had assured the king of their military support. They were partly personal opponents of Lancaster, partly they had also lost confidence in his political abilities and possibilities and now supported the king again. Once again, the empire was faced with an open civil war. The moderate barons like Pembroke and Badlesmere tried to stop the greed of the king's favorites, especially Damory, in order to defuse the conflict with Lancaster. From November 1317 to August 1318, the moderate barons negotiated with Lancaster to improve long-term relations between him and the king. The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of Dublin and Cardinals Luca Fieschi and Gaucelin , two papal ambassadors, took on a mediating position. In July 1318, when the King was in Northampton, Lancaster was at Tutbury , and the royal and ecclesiastical envoys traveled between the two places until an agreement was finally reached. On August 7th the King and Lancaster met and exchanged the kiss of peace, on August 9th they signed the Treaty of Leake near Nottingham , which was ratified by a parliament in York on October 20th. After the treaty, the ordinances were reconfirmed, the royal favorites left the court at least temporarily, and a permanent royal council was appointed. To this end, Parliament confirmed the appointments to the most important offices. However, this agreement was not beneficial to Lancaster. He himself was not a member of the royal council, whose members had the king's confidence. Even the royal favorites were no longer so obvious, but still present at court.

The Siege of Berwick

In April 1318 the important border town of Berwick had been conquered by the Scots , while the Scottish invading forces in Ireland under Edward Bruce were finally defeated in October 1318. In May 1319 a parliament in York decided on a campaign to retake Berwick. Although all leading magnates including Lancaster took part in the campaign, the king had to break off the siege that began on September 7th on September 17th after a Scottish army under Sir James Douglas had bypassed the English. The Scots sacked Yorkshire and on September 12 defeated an English army hastily mobilized by the Archbishop of York and the Bishop of Ely at the Battle of Myton , near York. The king now had to start negotiations with the Scots, which led to the conclusion of a two-year armistice at the end of December. After this debacle, Lancaster was suspected of facilitating the attack by the Scots, while Lancaster feared that the king would have taken military action against him after the capture of Berwick. In addition, Lancaster disapproved of the behavior of Hugh le Despenser, who had become Chamberlain of the royal Household in 1318 and had contributed to the failure of Berwick. Lancaster stayed away from the parliament in York on January 20, 1320, on which the king decided unusually briskly that he would travel to France in May to pay homage to the French king Philip V , who had ruled since 1316, for Aquitaine Gascony and sent to the Pope. It was also decided by parliament to move the administration, which had been in York since September 1318, back to Westminster. On June 19, 1320, the King and Queen traveled to France, where on June 29, they paid homage to Philip V in the Cathedral of Amiens for Aquitaine and Ponthieu. A few days later, the two kings met again to renew the friendship that Edward I and Philip IV had formed. A French council suggested that Edward II should also swear personal loyalty, which would have meant a stronger personal bond with the French king. This was strictly rejected by Edward II, which shows that he was very conscious of his royal dignity, even if he was influenced by numerous favorites. On July 22nd he traveled back to England with his Queen and reached London on August 2nd.

Despenser War and Civil War

The King was still full of energy and initiatives and was also actively involved in the discussions in Parliament. Lancaster, on the other hand, stayed away from parliaments, the reason for his reluctance was probably his rejection of the growing influence of the younger Despenser. Supported by the king, he tried to expand his possessions in South Wales at the expense of his neighbors. Against this expansion, the Marcher Lords joined together, which also Despenser's brothers-in-law Roger Damory and Hugh de Audley joined, as Despenser made their share of the legacy of the Earl of Hertford disputed. When Edward II seized the controversial Gower rule in South Wales on October 20, 1320 and handed over Despenser, Despenser’s opponents began preparations for an armed counter-attack under the leadership of the Earl of Hereford . Edward II and Despenser wanted to forestall the attack and left London on March 1, 1321. On March 27th they reached Gloucester , where the King called the Marcher Lords to a council meeting on April 5th. However, the Marcher Lords refused to appear and began the Despenser War on May 4th with an attack on Despenser's possessions in Wales . They were able to quickly conquer the Despenser estates in South Wales, whereupon Edward II called a parliament in Westminster for July 15, 1321 in the hope of protecting the Despenser estates from further attacks. Despite attempts by the bishops to mediate, the Marcher Lords appeared with their army in London on July 29th. They threatened the king's deposition if he did not banish the Despensers. On August 14th the king consented to the exile of the Despensers and on August 20th he officially pardoned the rebels.

However, the king now sought vengeance and immediately took action to bring the despensers back and destroy his opponents. Although Lancaster was allied with the Marcher Lords, he had not yet actively intervened in the fighting. Nor had he succeeded in forging a solid alliance between the rebels and the likewise opposition barons of northern England. Hoping that the rebel alliance would not last, the king met with the younger despenser on the Isle of Thanet and then proceeded against Bartholomew de Badlesmere, his former steward of the Household in Kent . Badlesmere had joined the rebels in the spring of 1321, but was also a bitter opponent of Lancaster. The king sent Queen Isabelle to Leeds Castle to be admitted to this Badlesmere castle. As expected, this was refused to her and her entourage on October 13, 1321, whereupon the king besieged the castle. The castle was captured on October 31st. As Eduard had hoped, the rebels had not been able to make a determined attempt at relief .

Both sides were now preparing an open war. At the beginning of December 1321, a meeting of the bishops called at short notice at Edward's request, in which only the Archbishop of Canterbury and four of the sixteen English bishops took part, declared the exile of the Despensers to be invalid. The king had won the support of the Earls of Pembroke, Richmond and Arundel and his half-brother Edmund of Kent . On December 8th he left London with his troops and took action against the rebels in the Welsh Marches. On the initiative of the King, Welsh nobles under Gruffydd Llwyd attacked the castles of the Marcher Lords, and without having received any support from Lancaster, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore and his uncle Roger Mortimer of Chirk surrendered on January 22, 1322 in Shrewsbury . On February 6, more rebels surrendered in Gloucester while the Earl of Hereford, Hugh de Audley and Roger Damory fled to northern England to join Lancaster. The king gathered his troops at Coventry , for this he ordered Sir Andrew Harclay , the commander of the royal troops at Carlisle, to advance from the north against the rebels. On March 3, he met the Despensers in Lichfield . At Burton, the rebels tried unsuccessfully to prevent the passage of royal troops across the Trent , then Lancaster, Hereford and the remaining rebels fled northwards from the overwhelming forces. On their flight they were defeated on March 16, 1322 in the Battle of Boroughbridge by Harclay. Hereford fell while Lancaster was captured the next day. He was brought to the king at Pontefract on March 21 and executed on the same day. Badlesmere and 26 other rebels were subsequently executed, while the Mortimers, Hugh de Audley and numerous others remained in captivity. Their properties were confiscated and passed to the Crown. A few rebels were able to get their properties back against heavy fines, but over 100 nobles lost their property.

Authoritarian rule, overthrow and death

Elimination of the opposition

After the king's complete victory over the rebels, the king called a parliament in York, which began on May 2, 1322. In the Statute of York , the ordinances were repealed and future restrictions on royal power were declared invalid. With this, the king had fully regained his limited power since 1311. However, he confirmed six articles of the Ordinances that had proven useful and that were intended to reinforce his will to reform. In addition, Parliament confirmed the condemnation of Lancaster and formally lifted the banishment of the Despensers, whom the king richly rewarded with confiscated properties from the rebels. He raised the elder Despenser to the Earl of Winchester , while he raised the victorious Harclay to the Earl of Carlisle .

Another failure in Scotland

After defeating the aristocratic opposition, Scotland was the only remaining opponent of the king. Due to the Scottish conquests of Carlisle and Berwick, the English lacked a starting point for their border defense, and internal conflicts and insufficient resources had prevented effective English counter-attacks. Shortly after Lancaster's death, the king finally wanted to avenge the humiliating defeat of Bannockburn and ordered a campaign to Scotland on March 25, 1322. The English army marched into Scotland on August 12, but the Scots avoided open battle and withdrew north and destroyed all supplies. Edward II advanced as far as Edinburgh, but he lost numerous soldiers, including his illegitimate son Adam , to hunger and illness. The English had to withdraw again, and on September 10, 1322 the king reached Newcastle. Through this failed campaign, Edward II again lost a large part of the military reputation he had gained through his success over the rebels. But it got even worse. The Scots crossed the English border on September 30th, and King Robert the Bruce planned the capture of the English king. Although Edward II knew of the approach of the Scottish army, the English army was defeated and dispersed by the Scots on October 14, 1322 at the Battle of Byland . Edward II, who had stayed in the nearby Byland Abbey , was pursued by the Scots and had to flee to York, which he reached on October 18. Queen Isabelle, whom the king had left behind at Tynemouth Priory , was now behind enemy lines and was probably only able to save herself by a dangerous crossing over the sea. Andrew Harclay, the victor of Boroughbridge, made his own peace with King Robert the Bruce on January 3, 1323 and recognized Scottish independence. The enraged king immediately revoked this agreement and had Harclay arrested and executed on March 3rd for treason. Nevertheless, he now had to start negotiations with Robert the Bruce himself and on May 30, 1323 in Bishopthorpe near York, agree to a thirteen-year armistice. For the first time since 1294, England was at peace with all of its neighbors.

Tyrannical rule of the king and the despensers

The inner peace in England, however, was only superficial. Even after the suppression of Lancaster's rebellion, rebels were executed; the harsh punishment and expropriation of the rebels embittered the survivors and the relatives of the executed. The loyalty of the king's followers was severely strained by favoring the despensers. Although the younger Despenser had great influence, the king remained the main driver of politics in those years. The nobles and the parliaments did nothing against the strict rule of the king in these years, the parliaments and council assemblies had nothing to decide. The magnates were intimidated by the fate of the rebels and by high possible penalties. The king had free rein, his will was law at this time. He ruthlessly exploited the confiscated possessions of his opponents. With this income Edward II was not only able to repay his father's debts and wage a new war with France without levying new taxes, but also amassed a vast treasure, which by the end of his reign was £ 60,000, about an annual income corresponded to the king. On August 1, 1323, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore escaped from captivity in the Tower , starting a process that ended with the overthrow of the king three years later.

War with France

In October 1323 there was an incident in Saint-Sardos in southwestern France between a vassal of the English king and French officials. The good relations between England and France were thereby destroyed, and attempts to resolve the conflict peacefully failed. In August 1324 a French army invaded Gascony. Eduard II considered leading an army to southwest France himself, but ultimately sent his wife, Queen Isabelle, to France on March 9, 1325 to negotiate a peace with her brother, the French King Charles IV . Edward II was finally ready to travel to France himself and pay homage to Charles IV on August 29 in Beauvais for his French possessions, but then he accepted Charles IV's proposal to transfer his French possessions to his eldest son who should then pay homage to the French king. On September 2, Edward II transferred Ponthieu and Montreuil to his son Edward , and on September 10, the Duchy of Aquitaine. The heir to the throne left England on September 12th and paid homage to the French king on September 24th in Vincennes Castle near Paris, where his mother was also. After that, however, both Isabelle and the heir to the throne ignored Edward II's requests to return to England. In November 1325, Isabelle openly declared that she would not return to England until the younger Despenser had been removed from the royal court.

Fall and capture

The relationship between Edward II and his wife Isabelle had rapidly deteriorated by 1321 at the latest, which was mainly due to the influence of the younger Despenser on the king. It has not been established whether there was also a sexual relationship between the king and the Despenser. There is no doubt, however, that Despenser had managed to separate the king and queen. Isabelle had blamed Despenser for the king abandoning her at Tynemouth in 1322 so that she almost fell into the hands of the Scots, and she also blamed him for the occupation of their lands, which the king officially responded to had seized the French incursion into Gascony in 1324. As a result, she stayed in France in 1325 and made Despenser responsible for her separation from her husband. Part of the responsibility for this situation was possibly Despenser's wife Eleanor de Clare , a niece of the king, to whom the king had given supervision of the queen and the king's lands in 1324 and who even held the queen's seal. According to the chronicler Henry Knighton, Eleanor is said to have behaved like a queen during Isabelle's absence in France, while the so-called Hainault chronicler even claims that there was a sexual relationship between Edward II and his niece.

Isabelle herself began a relationship in France, probably in December 1325, with Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, who had escaped from the Tower . King Edward II probably learned this from members of the queen's household who disapproved of this relationship. The enraged king wrote a letter to King Charles IV of France dated March 18, accusing his wife of adultery, and presumably planned in the summer of 1326 to turn to the Pope about a divorce. As early as January and February 1326, the king had taken measures to ward off a possible invasion by Mortimer and Isabelle, who were supported by the Count von Hainault , the father of the fiancé of the heir apparent. On June 19, 1326 he wrote another sharp letter to his son in which he forbade him to marry and asked him to dutifully obey him as a son. Despite the king's arrangements, Queen Isabelle and her supporters landed in Orwell, Suffolk, on September 24th without resistance . The reign of Edward II now collapsed, and the king, abandoned by numerous followers, fled westward from London on October 2, together with the younger Despenser. They reached Gloucester on October 11th and Chepstow on October 16th . From there they tried to flee to the island of Lundy on October 21st to possibly reach Ireland, but because of adverse winds they had to sail to Cardiff . In South Wales they tried to recruit troops in the Despenser estates there, hoping to get support from the Welsh, as in 1321. On October 28, Edward II and Despenser reached the mighty Caerphilly Castle , where they left Despenser's eldest son Hugh and part of their treasure in the care of a strong garrison. They fled further west via Margam and Neath Abbey . The Queen and Mortimer had hired Henry of Lancaster , brother of Thomas of Lancaster, to pursue them. Betrayed by locals, Edward II, Despenser and their companion, reduced to a few men, were captured by men from Lancaster on November 16 in the dense forests of South Wales near Llantrisant . The second part of the treasure carried, about £ 13,000 left, was supposed to be brought from Neath to Swansea Castle , but it was stolen in the confusion of the king's arrest and could never be found.

Forced abdication

Edward II was taken to Monmouth Castle , a castle owned by Henry of Lancaster, where his seal was removed on November 20th. On December 5th he reached Kenilworth Castle . There he remained in the care of Lancaster. In the meantime, the Queen and the heir to the throne Edward had declared in Wallingford on October 15 that they wanted to free the kingdom, the Church and the king from the tyranny of Despenser, and on October 26 the heir to the throne was proclaimed Guardian of the Empire in Bristol . The older Despenser, captured in Bristol, was executed on October 27th and the younger Despenser on November 24th in Hereford. Mortimer and the Queen were now looking for a way to depose Edward II with a semblance of legality. The heir to the throne, Edward, called Parliament on October 28, 1327, to Westminster on behalf of the king. The king reportedly refused to attend, and on January 13 a list of the king's misconduct was submitted to Parliament, believed to have been drawn up by a secretary to Bishop John Stratford of Winchester. So he was

- personally incapable of governing, he had allowed others to rule and was ill-advised, but rejected the advice of the great and wise men of the kingdom and of all others,

- he engaged in activities that were inappropriate and unworthy of a king and neglected his kingdom through it,

- he was proud, greedy and cruel,

- he had lost the Kingdom of Scotland, parts of Gascon and Ireland, which his father had given him in peace, and had lost the friendship of the King of France and others,

- he had harassed the church and captured and murdered clergymen, he had also captured, exiled and dispossessed numerous magnates,

- he had disregarded his coronation oath , followed bad counsel and neglected his kingdom, but above all he was incorrigible and with no hope of improvement. These allegations are known and cannot be denied.

Even if these accusations were partly blurred and partly false, for example because he had not taken over Scotland in peace, his opponents regarded him as an incompetent ruler who no longer had to be owed respect and obedience. A delegation traveled to the imprisoned king in Kenilworth, where Bishop Adam Orleton of Hereford Edward II presented the indictments on January 20, 1327, asking him to abdicate to the throne in favor of his son. Under strong pressure, Edward II finally agreed. Sir William Trussell , on behalf of Parliament, revoked its homage to Edward II, and Sir Thomas Blount , the Steward of the Household, broke his staff. The heir to the throne was officially declared king on January 25th and was crowned at Westminster Abbey on February 1st.

Imprisonment and presumed death

The former king stayed in Kenilworth until he was presumably surrendered to Thomas de Berkeley and John Maltravers on April 2, 1327 after a conspiracy led by Dominican John Stoke tried unsuccessfully to free Edward. On April 6th, he reached Berkeley Castle . In July, another conspiracy, also led by a Dominican, Thomas Dunheved , failed in an attempt to get Edward out of the castle. On September 14th, the Welshman Sir Rhys ap Gruffydd is also said to have tried to free Edward. Shortly afterwards, it was announced during parliament in Lincoln that the former king had died on September 21st. On October 22nd, his body was laid out in public in Gloucester, and on December 20, 1327, at St Peter Abbey , Gloucester, in the presence of his widow Isabelle and the young Edward III. to bury. His embalmed heart had previously been given to his widow. Edward III. later erected a splendid grave monument for his father.

Controversies over death

Although he officially died of natural causes, it was soon suspected that the former king was murdered. However, it was only after the fall of Roger Mortimer in 1330 that it was openly claimed that Edward II was murdered. In November Thomas Gurney and William Ockley were sentenced to death in absentia for the murder, while Thomas de Berkeley was exonerated by a jury in January 1331. John Maltravers was convicted of another offense and had to live in exile for many years before he was allowed to return to England. Since Gurney and Ockley were never tried in England, the exact circumstances of Eduard's death could never be clarified. There are several theories about the course of the alleged murder, including whether Mortimer ordered the murder after the unsuccessful rescue attempts or whether the guards panicked the king after the rescue attempts. Allegedly, as a brutal allusion to his suspected homosexuality, Eduard was driven a glowing iron rod through a sawn-off cow horn into the anus so that the corpse did not show any traces of external violence. However, this representation cannot be proven. It is most likely that Edward II died on September 21, but whether through natural death or murder cannot be proven. Still, rumors never fell silent that the former king was actually freed from Berkeley Castle. In 1330 his half-brother Edmund of Kent was executed because he supposedly wanted to reinstate Edward as king. In September 1330 Pope John XXII wrote. in a letter to King Edward III. and to Isabelle that he was amazed at how someone was solemnly buried and yet was alive. In September 1338 a certain William le Galeys (William the Welsh) appeared in Cologne , from where he was brought to Koblenz, where at that time a meeting of Edward III. took place with the Roman-German Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian . The later Bishop of Vercelli in Italy, Manuele Fieschi , also wrote a letter to the English king in 1336 or 1338, according to which Edward II had traveled through Europe after his liberation and finally died as a hermit near Cecima in Lombardy .

Aftermath

Edward II regularly attended church services and was considered exceptionally pious. In 1317 or 1318 he believed in a supposedly miraculous oil brought to him by an unscrupulous Dominican named Nicholas Wisbech, which could solve all his problems at one go. Like his father and grandfather, Eduard was an admirer of St. Edward the Confessor , he was also an admirer of Thomas Becket . He maintained a close relationship with the Dominican Order until his death, and Dominicans had been involved in the liberation attempts at least twice. Therefore, the canonization of the late king was soon demanded, similar to the canonization of Thomas of Lancaster had already been demanded in 1322. These efforts were supported by the Dominican Order. Finally, his great-grandson King Richard II , who also had close ties to the Dominican Order, asked the Pope to initiate canonization in 1385 and had a collection of supposed miracles created by King Edward II, which Pope Boniface IX at the beginning of 1395 . was handed over in Florence. However, the case was dropped when Richard II himself was deposed in 1399 and was never resumed.

In 1336 Queen Isabelle donated soul masses in Eltham Palace not only for her deceased son John, but also for her dead husband. When she died in 1358, she was buried in her wedding cloak from 1308, and Edward's embalmed heart, kept in a casket, was placed over her chest.

Oriel College in Oxford , which he founded, commemorates the king .

progeny

Edward II had four children with his wife Isabelle de France :

- Edward III. (13 November 1312 - 21 June 1377), heir to the throne

- Johann (14 August 1316 - 13 September 1336), Earl of Cornwall 1328

- Eleonore (June 18, 1318 - April 22, 1355) ⚭ 1332 Rainald II of Geldern

- Johanna (5 July 1321 - 7 September 1362) ⚭ 1328 King David II of Scotland

He also had at least one illegitimate son whose mother is unknown:

- Adam FitzRoy († before September 30, 1322)

rating

The reign of Edward II was rated negatively early on, especially when compared to that of his father and son. With the exception of the chronicler Geoffrey Baker, who describes the sufferings and death of Edward as a sign of his holiness, the other contemporary and contemporary chroniclers were generally critical, if not hostile, of Edward. His memory was colored very negatively early on, probably also to increase the contrast to his successor. He had taken his office as king seriously and stubbornly rejected restrictions on his royal power. He was probably more educated than many thought and could also express himself remarkably clearly, as the astonished silent audience proved when he clearly rejected the proposed oath of allegiance to the French king in Amiens in 1320. Handsome, strong and athletic, he was a formidable figure and a good rider. Personally, he fought valiantly in battle. He enjoyed being around others and was considered generous with a shrewd sense of humor. As Easter 1314, the body of Alban of England in the Ely Cathedral has been shown, he noted that he the body of the same saints had seen elsewhere already a week earlier. However, its positive qualities were offset by its mistakes. His father had been so absorbed by his war with Scotland that he had not given his son enough opportunity to gain government experience by taking on responsibility. Eduard swam and rowed, which was considered unworthy of a king. He was undoubtedly cruel and ill-tempered, and terribly vengeful. In addition, he preferred his favorites such as Gaveston and later the Despensers, who, through their behavior, aroused not only rejection, but also hostility among the English nobility and his own wife. He probably played a bigger role in day-to-day politics than is often assumed. In crises like 1321 and 1322 he could act very decisively, but his activities were not permanent, so that he could often be influenced by favorites.

Numerous biographies and books were written about Edward II in later centuries. The drama Edward II by Christopher Marlowe , composed around 1592, emphasizes the king's alleged homosexuality with unusual clarity. Bertolt Brecht edited the play in 1923 , and Derek Jarman's film Edward II (1991) is also based on the drama. Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland , in his The History of the most Unfortunate Prince King Edward II emphasized the king's dependence on his favorite Despenser. The book was written around 1627 and clearly referred to the relationship between King Charles I and his favorite Buckingham , which is why it could not appear until 1680.

Most of the historians of the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as William Stubbs , Thomas Frederick Tout and JC Davies, placed constitutional questions and the conflicts between Edward and his magnates at the center of their research, and they valued the importance of parliaments. In more recent research, Edward II is viewed in a more differentiated manner. From the 1970s onwards, the complex, partly personal relationships from the time of Edward II were examined in more detail. As recent individual studies have shown, Edward II was not an incompetent politician or administrator (even in comparison with the achievements of his father). But he did not succeed in reaching a sovereign consensus. Seymour Phillips, who in 2010 both submitted the current authoritative biography and wrote the article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , describes how Edward inherited a heavy legacy from his father with high debts and an unsolved war with Scotland. The war with Scotland was difficult to win, but it was politically unthinkable to give it up. In addition, he inherited a deep distrust of his powerful magnates, who strove for reforms and more power. His determination to protect his royal rights and his favorites (especially the Despenser family) was so extreme that a longer-term compromise with his opponents was impossible. Phillips judges the rule of Edward, who was a complicated character, balanced: Eduard was certainly not an important king, but he was probably undervalued during his lifetime, but certainly in modern times.

The humiliating assassination of Gaveston in 1312 finally led to the civil war from 1321 to 1322 and then to Edward's dismissal in 1326. In the latest (albeit brief) biography of the king, Christopher Given-Wilson comes to a rather critical assessment of Edward, who was not up to the tasks of his office be. With Edward II, force was used against an English king for the first time since the Norman conquest; this was repeated with Richard II and increased during the Wars of the Roses .

literature

- Roy Martin Haines: King Edward II: Edward of Caernarfon, his life, his reign, and its aftermath 1284-1330 . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montréal 2003, ISBN 0-7735-2432-0 .

- Gwilym Dodd, Anthony Musson (Eds.): The Reign of Edward II. New Perspectives . York Medieval Press, Woodbridge 2006, ISBN 1-903153-19-0 .

- Natalie Fryde: The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II, 1321-1326 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1979, ISBN 0-521-54806-3 .

- Christopher Given-Wilson: Edward II. The Terrors of Kingship (Penguin Monarchs) . Allen Lane, London 2016, ISBN 978-0-14-197796-6 .

- Seymour Phillips: Edward II (Yale English Monarchs) . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-17802-9 . (Standard work)

- JR S [eymour] Phillips: Edward II [Edward of Caernarfon] (1284-1327), king of England and lord of Ireland, and duke of Aquitaine. In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), as of January 2008

- Thomas Frederick Tout : Edward II of Carnarvon . In: Leslie Stephen (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 17: Edward - Erskine. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1889, pp. 38 - 48 (English).

Web links

- King Edward II in nndb (English)

- Edward II, King of England on thepeerage.com

Remarks

- ^ The Official Website of The British Monarchy: History of Monarchy. Edward II (r. 1307-1327). Retrieved August 5, 2015 .

- ↑ BBC Wales History: Caernarfon Castle. Retrieved August 5, 2015 .

- ↑ John Robert Maddicott: Thomas of Lancaster, 1307-1322. A Study in the Reign of Edward II. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1970, p. 83.

- ↑ Alison Weir: Isabella. She-Wolf of France, Queen of England . London, Pimlico 2006, ISBN 0-7126-4194-7 , p. 20.

- ↑ Michael Prestwich: Plantagenet England. 1225-1360. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2007. ISBN 0-19-822844-9 , p. 180

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7 , p. 102.

- ^ William Arthur Shaw: The Knights of England. Volume 1, Sherratt and Hughes, London 1906, p. 111.

- ^ Noel Denholm-Young: Vita Edwardi Secundi; monachi cuiusdam Malmesberiensis. Nelson, London 1957, Clarendon Press, Oxford 2005. ISBN 0-19-927594-7 , p. 136

- ↑ David Sutton: Kidwelly and the lost treasure of Edward II (Kidwelly History). Retrieved August 5, 2015 .

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7 , pp. 542

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7 , pp. 547

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7 , p. 565

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7 , p. 364

- ^ WM Ormrod: Edward III . Yale University Press, New Haven 2011, ISBN 978-0-300-11910-7 , p. 67

- ^ English Monarchs: Edward II. Retrieved August 6, 2015 .

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7 , p. 581

- ^ Ian Mortimer: The greatest traitor. The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, Ruler of England, 1327-1330. Pimlico, London 2003, ISBN 0-7126-9715-2 , p. 244

- ^ Gwilym Dodd, Anthony Musson (ed.): The Reign of Edward II. New Perspectives . Woodbridge 2006.

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II. New Haven 2010. Specialist reviews, inter alia, in The English Historical Review CXXVI, Issue 520 (2011), pp. 655-657 and in The American Historical Review 116 (2011), pp. 859f.

- ↑ Seymour Phillips: Edward II. New Haven 2010, pp. 607ff.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Edward I. |

King of England 1307-1327 |

Edward III. |

| Edward I. |

Lord of Ireland 1307-1327 |

Edward III. |

| Edward I. |

Duke of Aquitaine 1306–1325 |

Edward III. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Edward II |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Edward II .; Edward II of Carnarvon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of England and Wales (1307-1327) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 25, 1284 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Caernarvon , Wales |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 21, 1327 |

| Place of death | Berkeley Castle , Gloucestershire |