Erromintxela

| Erromintxela | ||

|---|---|---|

|

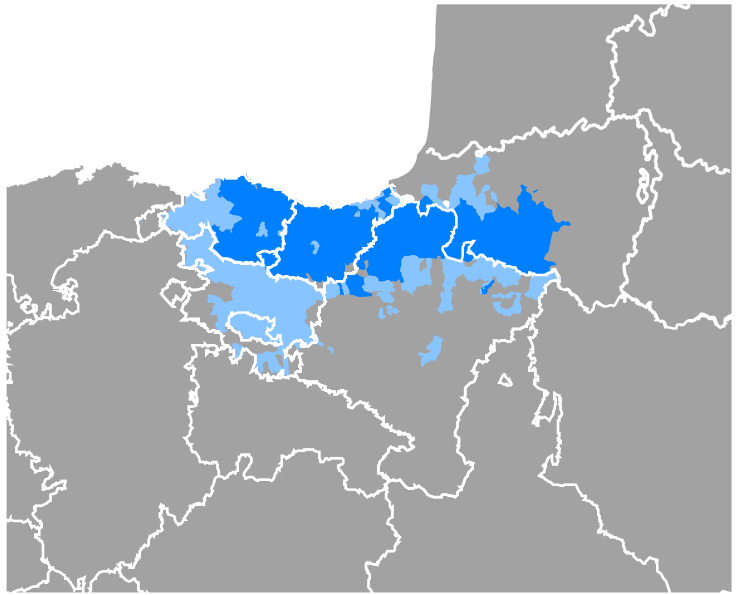

Spoken in |

Language possibly already extinct (2010) Number of speakers = approx. 500–1000 (1997) |

|

| speaker | Erromintxela (own name) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

NV |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

- |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

emx |

|

Erromintxela erominˈtʃela is the language of a group of Roma (from the Romani subgroup) who live in the Basque Country and are also known under the name Errumantxela. It is sometimes called the Basque Caló ; caló vasco, romaní vasco, or errominchela in Spanish; and euskado-rromani or euskado-romani in French. Although detailed information on the language dates back to the late 19th century, linguistic research did not begin until the 1990s.

Erromintxela language is a hybrid language that the majority of their vocabulary from the Kalderash - Romani concerns and also the Basque applies grammar, similar to the Anglo-Romani Roma in England mixes the Romani vocabulary of English grammar. The development of this mixed language was facilitated by the unusually deep integration of the Erromintxela people into Basque society and the resulting bilingualism in Basque. Language is slowly dying out; most of the perhaps 1,000 remaining speakers live on the coast of Labourd and in the mountainous regions of Soule , Navarra , Gipuzkoa and Biscay . The Erromintxela are descendants of the Kalderash Roma immigration in the 15th century who came to the Basque Country via France. They differ both ethnically and linguistically from the (Spanish-Romani) -speaking Roma in Spain and the Cascarot- Roma of the northern Basque Country .

Surname

The origin of the name Erromintxela is unclear and may be of relatively recent origin; Basques used to have the Erromintxela with more general terms for Roma such as B. ijitoak "Egyptians", ungrianok "Hungarians", or buhameak " denotes Bohemia ", a name that is prevalent near the Pyrenees and particularly in the northern Basque Country . Romanichel , on the other hand, is a French rendering of the Romani idiom Romani čel "Romani person". Although this name is now uncommon in France, it can be found in the names of the British Ròmanichal . as well as the Scandinavian , Romanisæl , all descendants such as the Erromintxela, a group of Roma who had migrated to France.

Early references to the name in Basque include Errama-itçéla, Erroumancel, later errumanzel and erremaitzela. The initial E- is the Basque prosthetic vowel added because no Basque word can begin with an R-, and the ending -a is the absolute suffix used when quoting a name. If this etymology is correct, this is the rare case of an original Romani self-name ( endonym ) borrowed from another language.

The people call themselves ijitoak Basque for English: "gypsies", or more precisely as Erromintxela in contrast to Caló Romani, which they call xango-gorriak, Basque for English "red-legs" (German: "Rotbeinige").

State of the language

There are currently an estimated 500 speakers in the southern Basque Country in Spain, around 2% of the population of 21,000 Roma , plus an estimated 500 in France. In Spain the remaining fluent speakers are older people, mostly over 80 years old; some speak Spanish, Basque or Caló (Spanish-Romani) just as fluently . Middle-aged Erromintxela are mostly passively bilingual and the youngest only speak Basque or Spanish. In the northern Basque Country, the language is still passed on to children. The percentage of speakers among the Spanish Erromintxela is greater than 2%, as large numbers of Caló-speaking Roma moved to the Basque Country during the heavy industrialization of the 20th century.

Literature in Erromintxela

Little literature has been written in this language to date. The most notable work is a poem by Jon Mirande , who published the poem entitled Kama-goli in his 1997 anthology Orhoituz . and the 1999 novella Agirre zaharraren kartzelaldi berriak by Koldo Izagirre Urreaga with a hero who uses the language.

history

The Erromintxela reached the Basque Country in the 15th century, as speakers of the Kalderash Romani. They integrated themselves into Basque society much more than other Roma groups. During this process they learned the Basque language and adapted aspects of Basque culture such as: B. more rights for women and important traditions eg bertsolaritza (improvised poetic singing) and pelota (national Basque ball game). Muñoz and Lopez de Mungia suggest that the morphological and phonological similarities between Romani and Basque made it much easier for bilingual Roma to adapt Basque grammar.

It seems that many Roma are determined to stay in the Basque Country to avoid persecution elsewhere in Europe. Nonetheless, even here they were not always safe from persecution. So issued z. For example, the Royal Council of Navarre issued an edict in 1602 to round up all "vagabonds" (pronounced Roma) who were then to be sentenced to 6 years galley . By the 18th century, however, attitudes had changed and the emphasis shifted towards integration. For example, in the years 1780–1781, the Navarre Courts of Justice enacted Law No. 23, which "called on the authorities to look after them, obtain settlement areas for them, and enable them to live and work respectably ..."

research

The oldest description of the language dates back to 1855, when the French ethnographer Justin Cenac-Moncaut described that Erromintxela is mainly found in the northern Basque Country. The oldest coherent text in Erromintxela, a poem entitled Kama-goli, was published in a collection of Basque poetry by Jon Mirande (circa 1960).

The 40-page study by Alexandre Baudrimont Vocabulaire de la langue des Bohémiens habitant les pays basques français (German: "Vocabulary of the language of the Bohemians living in the French Basque Country") from 1862, is one of the most extensive early evidence and includes both vocabulary as also grammatical aspects. Baudrimont worked with two informants, a mother and her daughter from Uhart-Mixe , an area near Saint-Palais , both of whom he describes as "fluent speakers". Unfortunately, he was only able to hold a single session when the women were told not to work with him any longer for fear of outsiders spying on Romani's secrets. Baudrimont's publication is in part problematic - he himself notes that he could not always be sure whether the correct forms were collected. For example, most of the verb forms he tried to raise lacked the expected verb ending -tu and instead appeared to be participles .

The French sociologist Victor de Rochas refers to the Roma in the northern Basque Country who spoke Basque instead of French, in his 1876 book Les Parias de France et d'Espagne (cagots et bohémiens) (German: Die Paria Frankreichs und Spaniens ( Cagots and Gypsies / Bohemians)). The canons Jean-Baptiste Daranatz published a list of words in the periodical Eskualdun Ona in 1906 and in 1921 Berraondo and Oyarbide did some investigations on the subject. Although often labeled as gitano (Spanish for Roma) or bohémien / gitan (French for Bohemian / Bohemian / Gypsy ), some dates are in Resurrección María de Azkues (an influential Basque priest, musician, poet, writer, boatman and academic, (* August 5, 1864; † November 9, 1951)) dictionary published in 1905 and Pierre Lhandes (Basque-French priest; July 9, 1877; † April 17, 1957) dictionary published in 1926.

Until the late 20th century, there was little further research into the language. In 1986, Federico Krutwig published a short article in the Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos (German: International Journal for Basque Studies) entitled "Los gitanos vascos" ("The Basque Gypsies") with a short list of words and a brief analysis of the morphology the language. Be that as it may, the most detailed study to date was published by the Basque philologist Josune Muñoz and the historian Elias Lopez de Mungia, which was carried out in the southern Basque Country in 1996 at the request of the Roma organization Kalé Dor Kayiko , with the support of Euskaltzaindia and the University of the Basque Country, started their work. Kalé Dor Kayiko, an organization that campaigns for the Spanish Caló and Romani, had learned of the existence of the Erromintxela in the 1990s through an article by the historian Alizia Stürtze entitled Agotak, juduak eta ijitoak Euskal Herrian (German: Agotes , Jews and Gypsies in the Basque Country). Kalé Dor Kayiko intends to continue the study of the language, behavior, identity and history of the Erromintxela in the less well-studied provinces of Navarre and the northern Basque Country.

Linguistic features

The research by Muñoz and Lopez de Mungia has confirmed that Erromintxela is not derived from Caló (Spanish Romani) spoken throughout Spain, but is instead based on Kalderash Romani and Basque. The vocabulary seems to be almost entirely of Romani origin; however, the grammar, both morphology and syntax, is derived from various Basque dialects. Only a few traces of the Romani grammar structures seem to have remained. The language is incomprehensible to both Basque and Caló speakers.

Typologically, Erromintxela has the same characteristics as the Basque dialects from which it derives its grammatical structures. Their case marking follows the ergative-absolutive pattern, where the subject of an intransitive verb is in the absolute (which is not marked) and which is also used for the direct object ( patient ) of a transitive verb . The subject ( agent (linguistics) ) of a transitive verb is marked with the ergative . Similarly, auxiliary verbs also match the subject and any direct and indirect object and verb forms present are allocated allocatively (i.e., a marker is used to indicate the gender of the addressee).

Since both Erromintxela and Caló are derived from Romani, many Erromintxela words are similar to the Spanish and Catalan caló.

| Erromintxela | Caló | Stem | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| baro | varó / baró | baró | big |

| dui (l) | dui | dúj | two |

| Guruni | guruñí | gurumni | Cow f. |

| kani (a) | casní, caní | khajní | Hen f., Chicken n. |

| latxo, latxu | lachó (fem. lachí) | lačhó | Well |

| mandro (a) | manró, marró | manró | Bread n. |

| nazaro, lazaro | nasaló (fem. nasalí) | nasvalí | Bread n. |

| panin (a) | pañí | paní | Water n. |

| pinro (a), pindru (a) | pinrró | punró | Foot m. |

| trin, tril | trin | trin | Tree m. |

| zitzai (a) | chichai | čičaj | big |

Phonology

According to Baudrimont's description from 1862 and also according to modern southern sources, the Erromintxela seems to have at most the following sound system. Southern officials have apparently not the rounded vowel / y / or the consonant / .theta / , in accordance with North Südunterschieden in Basque and it is unclear whether the distinction between northern / ɡ / and / ɣ / is also present in the south.

Consonant system

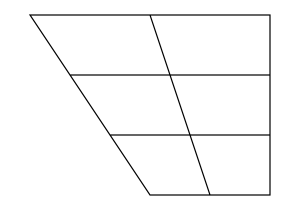

| Labial consonants | Coronal consonants | Dorsal (phonetic) consonants | Glottal consonants | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Dental |

Lamino- dental |

Apiko - alveolar |

Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velare | ||||||||||||

|

Nasals

Consonants |

m / m / |

n / n / |

ñ / ɲ / |

||||||||||||||||

|

Plosives

Consonants |

p / p / |

b / b / |

t / t / |

d / d / |

k / k / |

g / ɡ / |

|||||||||||||

|

Affricates

Consonants |

tz / ts̻ / |

ts / ts̺ / |

tx / tʃ / |

||||||||||||||||

|

Fricatives

Consonants |

f / f / |

/ θ / |

z / s̻ / |

s / s̺ / |

x / ʃ / |

j / x / |

/ ɣ / |

h / h / |

|||||||||||

|

Lateral

Consonants |

l / l / |

ll / ʎ / |

|||||||||||||||||

| R h o t i z i t ä t |

vibrant

Consonants |

rr / r / |

|||||||||||||||||

| Tonguing consonants | r / ɾ / |

||||||||||||||||||

Vocal system

(Comparison table IPA on the right)

| Vowels | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

For pairs of symbols (u • g) the left symbol stands for the unrounded vowel, the right symbol for the rounded vowel. |

||||||||||||||||||

| Front | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rounded | unrounded | ||||

| Closed | i i |

ü ( y ) |

u u |

||

| Half closed | e e |

o o |

|||

| Open | a a |

||||

Baudrimont uses a semi-phonetic system with the following different conventions:

| Baudrimont | u | ȣ | y | Δ | Γ | χ | sh | tsh | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | / y / | / u / | / y / | / θ / | / ɣ / | / x / | / ʃ / | / tʃ / | / z / |

morphology

Example of morphological features in Erromintxela:

| Erromintxela | Basque | Stem | Function in Erromintxela | example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -a | -a | Basque -a | Absolute suffix | phiria "the pot" |

| -ak | -ak | Basque -ak | Plural suffix | sokak "overcoats / coats" |

| -(on | -(on | Basque - (a) n | Locative suffix | khertsiman "in the restaurant" |

| - (a) e.g. | - (a) e.g. | Basque - (a) z | Instrumental suffix | jakaz "with (tels) fire" |

| - (e) k | - (e) k | Basque - (e) k | Ergative suffix | hire dui ankhai koloek "with your two black eyes" |

| -ena | -ena | Basque -ena | Superlative suffix | loloena "reddest, -e, it" |

| - (e) ko (a) | - (e) ko (a) | Basque - (e) ko (a) | local genitive suffix | muirako "of the mouth" |

| - (e) rak | - (e) rat (North Basque) | Basque - (e) ra (t) | Allative suffix | txaribelerak "to the bed (towards)" |

| -pen | -pen | Basque pen | 1) Suffix denoting an action or effect

2) under |

|

| -ra | -ra | Basque -ra | Allative suffix | penintinora "to the small brook (towards)" |

| -tu | -tu | Basque -tu | Verb-forming suffix | dekhatu "see" |

| -tzea | -tzea | Basque -tzea | Nouning | |

| - etch | -t (z) en | Basque -t (z) en | Past tense suffix | kherautzen "to be there to do" |

Verb formation

Most verbs have a Romani stem with the Basque verb suffix -tu. Examples of Erromintxela verbs are given below. (Shapes in square brackets indicate the spelling in sources that are no longer used. Basque is included for comparison purposes.)

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| brikhindu | euria izan | brišínd | rain |

| burrinkatu | harrapatu | (astaráv) | hold on, catch |

| dikelatu, dekhatu | ikusi | dikháv | see |

| erromitu (eŕomitu) | ezkondu | marry | |

| gazinain kheautu | haur egin | to give birth (lit. to make a child) | |

| goli kherautu, goli keautu | kantatu | (gilábav) | to sing (lit. to make a song) |

| kamatu | maitatu | kamáv | love |

| kerau, keau, kherautu, keautu | egin | keráv | 1) do, do 2) auxiliary verb |

| kurratu | lan egin | butjí keráv | work |

| kurrautu ‹kuŕautu› | jo | hit, hit | |

| kuti | begiratu | dikáv | look, look at |

| letu | hartu | lav | to take |

| mahutu, mautu | help | mu (da) ráv | die, kill |

| mangatu | eskatu | mangáv | ask, ask |

| mukautu | bukatu | end up | |

| najin | bukatu | end up | |

| papira-keautu | idatzi | (skirív, ramóv) | to write (lit. to make paper) |

| parrautu ‹paŕautu› | ebaki | to cut | |

| pekatu | egosi | pakáv | Cook |

| pekhautu | achieve | burn | |

| piautu | edan | pjav | drink |

| tarautu, tazautu | ito | choke, strangle | |

| partaitu | Jan | xav | eat |

| tetxalitu, texalitu | ibili | go for a walk, go, run, hike | |

| txanatu | jakin | žanáv | know |

| txiautu | ram in, push in | ||

| txoratu, xorkatu ‹s̃orkatu› | lapurtu, ebatsi | čoráv | steal |

| ufalitu | their egin | to flee | |

| xordo keautu | lapurtu, ebatsi | to steal (lit. "to steal") | |

| zuautu | lo egin | sováv | sleep |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

Most of the Erromintxela verb inflections are virtually identical to those in the Basque dialects.

| Erromintxela | Basque ( Lapurdian ) | translation |

|---|---|---|

| ajinen duk | izanen duk | you will have |

| dekhatu nuen | ikusi nuen | I saw it |

| dinat | diñat | I am (family addressee) |

| erantzi nauzkon | erantzi nauzkan | I took it off |

| ... haizen hi | ... haizen hi | ... that you are (? -Engl .: you are) |

| kamatu nuen | maitatu nuen | I loved it |

| letu hindudan | hartu hintudan | you took me |

| nintzan | nintzan | I was |

| pek skin nina | to blush naute | You burn me |

| pekhautu nintzan | reach nintzen | I ( intransitively ) burned |

| pek skin niagon | blush niagon | I ( intransitive ) was burning (addressee) |

| tetxalitzen zan | ibiltzen zan | I was about to leave |

| zethorren | zetorren | It came |

| zoaz | zoaz | Go Get lost! (? -English: You go!) |

Negations are formed with na / nagi (Romani na / níči ); see. Basque ez / ezetz . The word for "yes" is ua (Romani va ); see. Basque bai / baietz .

noun

The majority of nouns have Romani stems, but often with Basque suffixes. The variation of nouns quoted with or without an ending -a is likely due to informants who use it with or without an absolute ending . (Shapes in square brackets indicate spellings in sources that are no longer used.)

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| angi | ezti | (avdžin) | Honey m. |

| ankhai | begi | (jakh) | Eyes. |

| asinia | botila | (fláša) | Bottle f. |

| balitxo | txerriki | baló "pig" with a Basque suffix | Pork (without article) / pork n. |

| barki | ardi | bakró | Aue f./Zibbe f./Ewe n., Sheep n. |

| barkitxu, barkotiñu, barkixu (barkicho) | arkume | bakró "sheep n." plus Basque diminutive -txu, tiñu | Lamb n. |

| barku | ardi | bakró | Sheep n. |

| basta, basta | esku | vas (t) | Hand f., Arm m. |

| bato, batu | aita | dad | Father m. |

| bedeio (bedeyo) | alder | (daraši) | Bee f. |

| bliku | txerri | from balikanó mas "pork" | Pig n. |

| bluiak | police officer | (policájcur) | Police officers pl. |

| budar, budara | ate | vudár | Door f. |

| burrinkatzea | harraptze | Act of catching | |

| dantzari | dantzari | (Basque word stem) | Dancer m. |

| dibezi | egun | djes | Day m. |

| duta | argi | udút | (natural) blonde |

| egaxi | gaží | a non-Romni | |

| egaxo, ogaxo, egaxu | gažó | a Gadže / non-Roma | |

| elakri, ellakria | neska (til) | raklí | Girl n. |

| elakri-lumia | Woman with a bad reputation | ||

| eramaite | erama (i) te | bringing | |

| eratsa, erhatsa, erhatza, erratsa (erratça) | ahate | (goca) | Duck f. |

| erromi (eŕomi), errumi, errumia | senar | Rome | 1) husband m.

2) wedding |

| erromiti, errumitia | emazte | romní | Wife f. |

| erromni | emazte, emakume | romní | Woman f., Wife f., Woman n. |

| erromitzea | eskontza | (bjáv) | Wedding f. |

| erromitzeko (eŕomitzeko), erromitzekoa | eraztun | (angruští) | (der) Ring (lit. "the marriage candidate" - English: the one to marry) |

| fula | kaka | khul | Excrement n., Excretion f. |

| futralo | Eau de vie n. (Lit.water of life) | ||

| gata | ator | gad | Shirt n. |

| magazine | haur | Child n. | |

| giltizinia | validza | (čája) | Key m. |

| goani | zaldi | (grazes) | Horse n. |

| goia | lukainka | goj | Sausage f., Sausage n. |

| goli | kanta | gilí | Song n. |

| grasnia, gasnia, grasmiña, gra | zaldi | grass (t) | Horse n. |

| guru, gurru ‹guŕu› | idi | gurúv | Ox |

| Guruni | behi | gurumni | Cow f. |

| gurutiño | txahal | gurúv plus a Basque diminutive -tiño | Calf n. |

| haize | haize | (Basque word stem) | Wind m. |

| jak, jaka, zaka, aka | see below | hunt | To fire. |

| jakes | gazta | (királ) | Cheese m. |

| jera, kera (kéra) | asto | (esa) | Donkey |

| jero | buru | šeró | Head m. |

| jeroko | buruko | Beret (lit. "from the head") | |

| juiben, juibena | galtzak | (kálca) | Trousers pl. |

| kalabera | buru | (šeró) | Head m. Compare Spanish calavera , "skull" |

| kalleria ‹kaĺeria› | Silverware pl. Compare Spanish quincallería , "Blechwaren pl." | ||

| kalo, kalu, kalua | coffee | (káfa) | Coffee m. |

| kalo-kasta | ijito-kastaro | Romani parish, district | |

| camat | maitatze | <kamáv | loving |

| kangei, kangey; kangiria | eliza | kangerí | Church f .; Baudrimont glosses "Altar" |

| kani, kania | oilo | khajní | Hen f., Chick n. |

| kaxta, kasta (casta), kaixta (kaïshta) | to | kašt | Wood n., Branch m., Stick m. |

| kaxtain parruntzeko ‹paŕuntzeko› | aizkora | Ax f. | |

| kher, khe, kere, khere, kerea | etxe | kher | House n. |

| kereko-egaxia ‹kereko-egas̃ia› | etxeko others | Landlady f. | |

| kereko-egaxoa ‹kereko-egas̃oa›, kereko-ogaxoa | etxeko jauna | Landlord m. | |

| ker-barna | gaztelu | (koštola) | Castle f., Fort n., Castle n. |

| ker, qer, kera | asto | (esa) | Donkey |

| kero, keru, kerua | buru | šeró | Head m. |

| khertsima | taberna | Restaurant f., Inn n. | |

| kiala, kilako | gazta | királ | Cheese m. |

| kilalo | cold air f. | ||

| kirkila | babarruna | (fusúj) | Bean f. |

| konitza, koanits, koanitsa | saski | kóžnica | Basket w. |

| laia | jauna | Mr. m. | |

| lajai, olajai, lakaia | apaiz | (rašáj) | Priest |

| laphail, lakhaia | apaiz | (rašáj) | Priest |

| latzi, latzia | gau | Night f. | |

| lona | gatza | lon | Salt n. |

| mahutzea, mautzia | hiltzea | mu (da) ráv (v.), plus the Basque nominalization suffix -tzea | Killing n. (See mahutu v.) |

| malabana | really | (thuló mas) | Lard n. |

| mandro, mandroa | ogi | manró | Bread n. |

| mangatzia | eske | mangáv (v.), plus the Basque nominalization suffix -tzea | Begging n. |

| marrun (maŕun) | senar | Husband m., Husband m. | |

| mas, maz, maza, masa (māsa) | haragi | mas | Meat n. |

| megazin, megazina | haur | Child n. | |

| milleka ‹miĺeka› | arto | Korn n. (Mais m.), Welschkorn n., Kukuruz m. | |

| milota | ogi | (manró) | Bread n. |

| milotare-pekautzeko | labe | Furnace m. | |

| Mimakaro | Ama Birjina | Our Lady | |

| miruni | emakume | Mrs. f. | |

| mitxai, ‹mits̃ai› | alaba | čhaj | Daughter f. |

| mol, mola | ardo | mol | Wine m. |

| mullon ‹muĺon›, mullu ‹muĺu› | mando | Mule n., Mule m. | |

| ñandro, gnandro | arraultz | anró | A. |

| oxtaben, oxtaban ‹os̃taban›, oxtabena | gartzela | astaripe | Prison n. |

| paba, phabana, pabana | sagar | phabáj | Apple m. |

| paba-mola | sagardo | Cider m. (lit. Apfelwein m.) | |

| panin, panina, pañia | ur | pají | Water n. |

| panineko, paninekoa | pitxer | (the) jug m., jug f. (lit. one for water) | |

| paninekoain burrinkatzeko ‹buŕinkatzeko› | Netz n. (?) (Lhande indicates: French fillet ) | ||

| paninbaru, panin barua | ibai, itsaso | (derjáv, márja) | River m., Ocean m. (lit.big water) |

| panintino, panin tiñua, penintino | ereka | (len) | Brook n. (Lit.small water) |

| pangua | larre | Meadow f. | |

| panizua | arto | Korn n. (Corn m.). Compare Spanish "panizo" | |

| papin, papina | antzar | papin | Goose f. |

| papira | paper | papíri | Paper n. |

| pindru, pindrua, pindro, prindo | hanka, oin | punró | Foot m. |

| pindrotakoa | galtzak | kálca | Pants pl., Pants f. (lit.the for the foot) |

| piri, piria | lapiko | pirí | Saucepan m., Saucepan m., Casserole f. |

| pora | urdaila | by | Stomach m. |

| potozi | diruzorro | Wallet f., (Money) purse f., Purse m. | |

| prindotako | galtzerdi | pinró (trousers) | Sock f. (lit.the for the foot) |

| puxka (pushka) | arma | puška | Pistol f., Weapon f. |

| soka | gaineko | Coat m., Overcoat m. | |

| sumia | zupa | zumí | Soup f. |

| thazautzia | itotze | taslaráv (v.), plus the Basque nominalization suffix -tzea | Act of throttling |

| tekadi, tekari | hatz | (naj) | Finger m. |

| ternu | gazte | young person f. | |

| txai ‹ts̃ai› | čhaj | young person (both sexes) | |

| txaja | aza | (šax) | Cabbage m. |

| txara | belar | čar | Grass n. |

| txaripen, txaribel | oh | (vodro) | Bed n. |

| txau, xau | seme | čhavó | Son m. |

| txipa | izen | (aláv) | Name m. |

| txiautu | ijito | a Roma | |

| txiautzia | ?, plus the Basque nominalization suffix -tzea | Act of ramming | |

| txohi, txoki | gona | Skirt m. | |

| txohipen, txohipena | Petty theft m. (lit. "under the skirt") | ||

| txor, txora ‹ts̃ora› | lapur | čor | Thief |

| txuri, txuria | aizto | čhurí | Knife n. |

| xordo, txorda ‹ts̃orda› | lapurketa | čoripé | Theft m., Robbery m. |

| xukel ‹s̃ukel›, txukel, txukela ‹ts̃ukela›, xukela (shȣkéla) | txakur | žukél | Dog m. |

| xukelen-fula ‹s̃ukelen-fula›, txukelen fula | txakurren kaka | Dog excrement m. | |

| xukel-tino keautzale | Bitch f. (lit. "little dog maker") | ||

| zuautzeko, zuautzekoa | estalki | duvet covers pl. | |

| zitzaia, zitzai, txitxai ‹ts̃its̃ai›, txitxaia, Sitzaia (sitçaia) | katu | čičaj | Cat f. |

| zume, sume | zupa | zumí | Soup f. |

| zungulu, sungulu, sungulua | tobacco | (duháno) | Tobacco m. |

| add, add a, xut, txuta, txuta ‹ts̃uta› | esne | thud | Milk f. |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

time

According to Baudrimot, the Erromintxela have adopted the Basque names of the months. Note that some of the Basque names that represent those prior to standardization, eg August, is Abuztua in Batua (Standard Basque) rather than Agorrila .

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otarila | Urtarrila | (januáro) | January m. |

| Otxaila (Otshaïla) | Otsaila | (februáro) | February m. |

| Martxoa (Martshoa) | Martxoa | (márto) | March m. |

| Apirilia | Apirilia | (aprílo) | April m. |

| Maitza (Maïtça) | Maiatza | (májo) | May m. |

| Hekaña (Hékaña) | Ekaina | (June) | June m. |

| Uztailla (Uçtaïlla) | Uztaila | (July) | July m. |

| Agorilla | Agorrila | (avgústo) | August m. |

| Burula | Buruila | (septémbro) | September m. |

| Uria | Urria | (októmbro) | October m. |

| Azalua (Açalȣa) | Azaroa | (novémbro) | November m. |

| Abendua (Abendȣa) | Abendua | (decémbro) | December m. |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

Baudrimont claims that subdivisions of the year (apart from the months) are formed by the word breja (bréχa) "year": breja kinua "month" and breja kipia "week".

Numerals

Numerals (including Basque for comparison purposes):

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| jek, jeka, eka, jek (yek), jet (yet) | asked | jék | one |

| dui, duil | bi | dúj | two |

| trin, trin, tril | hiru | trín | three |

| higa | higa (variant form) | (trín) | three |

| estard | lukewarm | star | four |

| pantxe, pains, olepanxi (olepanchi) | bost | panž | five |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

adjectives and adverbs

Adjectives and adverbs are mainly derived from the Romani forms:

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| baro, baru | handi | baró | big |

| bokali | gose | bokh | hungry |

| buter | asko, ainitz | but | a lot, a lot |

| dibilo | dilino | insane | |

| dibilotua | erotua | <dilino (adj.) | gone crazy, crazy |

| gift | gift | (Basque word stem) | without |

| eta | eta | (Basque word stem) | and |

| fukar | ederra | šukar | wonderful, wonderful |

| geroz | geroz | (Basque word stem) | once |

| hautsi | hautsi | (Basque word stem) | broken, broken |

| kalu | beltz | kaló | black |

| kaxkani | zikoitz | stingy, petty, stingy | |

| kilalo | hotz | šilaló | cold |

| latxo, latxu | on | lačhó | Well |

| londo | samur | soft | |

| nazaro, lazaro | eri | nasvaló | ill |

| palian | ondoan | near, near | |

| parno | garbi | parnó (white) | clean |

| telian | behean | téla | under |

| tiñu, tiñua | txiki | cignó | small |

| upre | gain (ean), gora | opré | up, up, up |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

Pronouns & demonstratives

Pronouns are derived from both languages:

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| aimenge | ni | mánge "mir", possibly called "us" ( dative forms ) | I |

| ene | ene | (Basque word stem) | my (pet form, loving) |

| harekin | harekin | (Basque word stem) | with him, with her ( distal ) |

| hari | hari | (Basque word stem) | you (family) |

| hard on | hard on | (Basque word stem) | in him, in her ( distal ) |

| hay | hay | (Basque word stem) | your (familial emphatic) |

| Hi | Hi | (Basque word stem) | you (family) |

| hire | hire | (Basque word stem) | your (family) |

| hiretzat | hiretzat | (Basque word stem) | for you (family) |

| mindroa | nirea | miró | my |

| neure | neure | (Basque word stem) | my (emphatic) |

| ni | ni | (Basque word stem) | I (intransitive) |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

Baudrimont's material

Much of Baudrimont's list of words is directly related to Erromintxela sources. Nevertheless, some of the material that Baudrimont has collected deserves a more detailed survey thanks to its particularities. Most of these relate to the verbs and verb forms he collected. However, some include nouns and other components.

noun

Its material contains a relatively high number of components derived from Basque.

| Erromintxela | Basque | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| aitza (aitça) | aritz | Oak f. | |

| aizia (aicia) | haize | (diha) | Air f. |

| eel | hegal | (phak) | Wing m. |

| itxasoa (itshasoa) | itsaso | (derjáv) | Lake f., Sea n., Ocean m. |

| keia (kéïa) | ke | (thuv) | Smoke m. |

| muxkera (mȣshkera) | musker | (gusturica) | Lizard f. |

| orratza (orratça) | orratz | (suv) | Needle f. (Basque orratz is "comb m.") |

| sudura (sȣdȣra) | sudur | (nakh) | Nose f. |

| ulia (ȣlia) | euli | (mačhin) | Fly f. (Insect n.) |

| xuria (shȣria) | (t) xori | (čiriklí) | Bird m. |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

Some components are special. Baudrimont lists mintxa as "tooth m." The Kalderash expression is dand ( daní in Caló), but the given expression is more reminiscent of the North Basque mintzo "language f., Speech f." or mintza "skin f." (with expressive palatalization ). This and other similar elements raise the question of whether Baudrimont simply pointed to objects in order to list the shapes.

The forms he has tried to raise are also questionable in some cases. For example, it targeted agricultural terms such as B. plow , harrow (agricultural engineering) and post-harvest from his (female) informants and draws the suspiciously similar words sasta "plow m." and xatxa (shatsha) "Egge f." on.

Verb system and pronouns

The verb system and pronouns that Baudrimont records are conspicuous in several ways. Apart from his problem of raising the basic form (? - English: citation form) of verbs in relation to participles, he lists pronouns and possessive pronouns that seem to contain Romani word stems and an unexpected auxiliary verb.

The verb ajin for "to have" is attested elsewhere, although forms derived from Basque are mostly more common. Kalderash Romani uses the third person of "sein" and a dative pronoun to indicate the owner.

| Erromintxela | Basque (allocative forms) | Romani * | Erromintxela translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| mek ajin (mec aχin) tuk ajin (tȣc aχin) ojuak ajin (oχuac aχin) buter ajin (bȣter aχin) tuk ajin (tȣc aχin) but ajin (bȣt aχin) |

(nik) di (n) at (hik) duk 1 / dun (hark) dik / din (guk) di (n) agu (zuek) duzue (haiek) ditek / diten |

si ma si tu si les / la si amé si tumé si len |

I have you have he / she has we have you have they have |

| mek najin (mec naχin) tuk najin (tȣc naχin) ojuak najin (oχuac naχin) buter najin (bȣter naχin) tuk najin (tȣc naχin) but najin (bȣt naχin) |

(nik) ez di (n) at (hik) ez duk / dun (hark) ez dik / din (guk) ez di (n) agu (zuek) ez duzue (haiek) ez ditek / diten |

naj / nané ma naj / nané tu naj / nané les / la naj / nané amé naj / nané tumé naj / nané len |

I do not have you do not have he / she does not have we do not have you do not have , they have not |

| mek naxano (mec nashano) tuk naxano (tȣc nashano) ojuak naxano (oχuac nashano) buter naxano (bȣter nashano) tuk naxano (tȣc nashano) but naxano (bȣt nashano) |

(nik) izanen di (n) at (hik) izanen duk / dun (hark) izanen dik / din (guk) izanen di (n) agu (zuek) izanen duzue (haiek) izanen ditek / diten |

ka si ma ka si tu ka si les / la ka si amé ka si tumé ka si len |

I will have you will have he / she will have we will have you will have they will have |

| * Romani of the English “North Central Romani” branch does not quite match the so-called “Central Group (Northern Branch)” in the German-language Wikipedia. The classification in the English Wikipedia is based on different classification criteria. (Note from the translator) | |||

1 Note that forms like duk (3rd pers-have-2nd pers (male)) are the verbal part, while in Erromintxela tuk is a pronoun.

The negative particle na is fairly distinct in the above forms. Buter , as Baudrimont notes, is the word for "much, many" and is possibly a real pronoun. Kalderash uses accusative pronouns to express possession, but the above forms are more reminiscent of the incorrect grammatical Kalderash dative forms mangé, tuké, léske, léke etc. and perhaps another case of "to be" (since the complete Kalderash paradigm is sim, san, si, si, sam, san / sen, si ) is.

Overall, questions arise regarding the level of communication between Baudrimont and his informants and the quality of (some) of the materials he has collected.

Compound examples

Examples with interlinear versions :

Annotation:

- There is no corresponding entry for the attributive noun in the German language Wikipedia; Perhaps next comes the noun phrase (Chomsky), but it is explained relatively poorly there.

- There is no corresponding entry for the allocative agreement in German-language Wikipedia. see. Allocation

| khere-ko | ogaxo-a |

| House ATTR | Mr. ABS |

| the master of the house | |

| hire-tzat | goli | kerau-tze-n | di-na-t | |||||

| your (informally) - BEN | song | mache- NMZ - LOC | ABS . 3SG - PRE DAT - FEM . Allok - ERG . 1SG | |||||

| I sing for you | ||||||||

| xau-a, | goli | keau | za-k, | mol | buterr-ago | aji-n-en | duk |

| boy- ABS | to sing | make | have- ERG . FAM . MASC | Wine | Rather COMP | have- PFV - FUT | ABS . 3SG -has- ERG . MASC . ALLOK |

| Boy, sing, you'll have more wine! | |||||||

| txipa | nola | you-to? | |||||

| Surname | how | ABS . 3SG -has- ERG . 2SG | |||||

| What's your name? | |||||||

| masa-k | eta | barki-txu-ak | pangu-an | daoz | |||||||

| Meat ABS . PL | and | Sheep DIM - ABS . PL | Meadow- LOC | ABS . 3SG - PRÄS -go- PL | |||||||

| The sheep and the lambs are in the meadow | |||||||||||

| nire | kera | to-a-ren | pali-an | dao, | themes | obeto-ao | dika-tu-ko | you-to | |||||||||||

| my | House | your- ABS - GEN | Proximity- LOC | ABS . 3SG - PRÄS - be located | here- OJ | better- COMP | see- PFV - FUT | ABS . 3SG -has- ERG . 2SG | |||||||||||

| My house is near yours, you can see it better from here | |||||||||||||||||||

literature

- A. Baudrimont: Vocabulaire de la langue des Bohémiens habitant les Pays Basque Français. (German: Vocabulary of the language of the Gypsies / Bohemia living in the French Basque Country. ) Academie Impérial des Sciences, Bordeaux 1862.

- R. Berraondo: La euskera de los gitanos. (German: The Basque of the Gypsies. ) In: Euskalerriaren Alde - Revista de Cultura Vasca 1921

- D. Macritchie: Accounts Of The Gypsies Of India (German: Reports about the Gypsies of India), 1886, Reprint: New Society Publications, New Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-1-4067-5005-8 .

- F. Michel: Le Pays Basque. (German: The Basque Country. ) Paris 1857.

Web links

- Kalé Dor Kayiko

- Full version of the Erromintxela poem with Basque translation (German: Vollversion des Erromintxela poem with Basque translation)

- Gitano in Spanish Auñamendia Encyclopedia.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Xabier Argüello: Ijito euskaldunen arrastoan. El País 2008.

- ↑ Ethnologue Sprachen of Spain Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ↑ Langues d'Europe et de la Méditerranée (LEM) La langue rromani en Europe Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ↑ Nicole Lougarot: bohemians. Gatuzain Argitaletxea 2009, ISBN 2-913842-50-X .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lore Agirrezabal: Erromintxela, euskal ijitoen hizkera. Argia, San Sebastián 2003.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Unai Brea: Hiretzat goli kherautzen dinat, erromeetako gazi mindroa. Argia, San Sebastián 2008

- Anyway , a number of authors believe that the name is the Basque rendering of the French name romanichel or romané-michel,

- ^ A b c d D. Macritchie: Accounts Of The Gypsies Of India. 1886, (German: Reports on the Gypsies of India. ), Reprint: New Society Publications, New Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-1-4067-5005-8 .

- ↑ M. Wood: In the Life of a Romany Gypsy. Routledge (publisher) , 1973, ISBN 978-0-7100-7595-6 .

- ^ Council of Europe "Roma and Travelers Glossary" Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ I. Hancock: A Glossary of Romani Terms, p. 182. In: W. Weyrauch: Gypsy Law: Romani Legal Traditions and Culture. University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-520-22186-4 .

- ^ P. Mérimée: Lettres a Francisque Michel (1848–1870) & Journal de Prosper Mérimée (1860–1868). Librarie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris 1930, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ a b c Auñamendi Entziklopedia "Diccionario Auñamendi - Gitano" Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ a b Óscar Vizarraga: Erromintxela: notas para una investigación sociolingüística. In: I Tchatchipen. Vol 33, Instituto Romanó , Barcelona 2001.

- ↑ a b Plan Vasco para la promoción integral y participación social del pueblo gitano. (German: Basque plan for the integral promotion and social participation of the Gypsy people. ) Basque Government (2005)

- ↑ P. Urkizu, A. Arkotxa: Jon Mirande Orhoituz - 1972-1997 - Antologia. San Sebastián 1997, ISBN 978-84-7907-227-8 .

- ^ J. Cazenave: Koldo Izagirre Urreaga. In: Auñamendi Entziklopedia. euskomedia.org Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg Jon Mirande: Poemak 1950-1966. Erein, San Sebastián 1984.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao A. Baudrimont: Vocabulaire de la langue des Bohémiens habitant les pays basques français (German: Vocabulary of the language of the Gypsies / Boers who inhabit the French Basque Country. ) Academie Impériale des Sciences, Bordeaux 1862.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd Jean-Baptiste Daranatz: Les Bohémiens du Pays Basque. (German: The Gypsies / Bohemians of the Basque Country. ) Eskualdun Ona # 38, September 1906.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm Federico Krutwig Sagredo: Los gitanos vascos. (German: The Basque Gypsies. ) In: Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos. Volume 31 (1986)

- ↑ a b I. Adiego: Un vocabulario español-gitano del Marqués de Sentmenat (1697–1762). Ediciones Universitat de Barcelona 2002, ISBN 84-8338-333-0 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Resurrección María de Azkue: Diccionario Vasco Español Frances. (German: Basque Spanish French Dictionary. ) 1905, Reprint: Bilbao 1984.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Mozes Heinschink, Daniel Krasa: Romani word for word. Gibberish 2004.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz ea eb ec ed ee ef eg eh ei ej ek el Pierre Lhande: Dictionnaire Basque-Français et Français-Basque. Paris 1926.

- ↑ Compare Sanskrit kama as in Kama Sutra .

- ^ Pierre Laffitte: Grammaire Basque Pour Tous. Haize Garbia, Hendaye 1981.

- ↑ a b Joxemi Saizar, Mikel Asurmendi: Argota: Hitz-jario ezezagun hori. Argia no.1704, San Sebastián 1999.

- ↑ a b c d Koldo Izagirre: Agirre Zaharraren Kartzelaldi Berriak. Elkar 1999, ISBN 84-8331-439-8 .

- ↑ Koldo Mitxelena: Diccionario General Vasco - Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia VI Dag-Erd. Euskaltzaindia , Bilbao 1992.

- ↑ Luis Mitxelena: Diccionario General Vasco - Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia VII Ere-Fa. Euskaltzaindia, Bilbao 1992.

- ↑ Luis Mitxelena: Diccionario General Vasco - Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia VIII Fe-Gub. Euskaltzaindia, Bilbao 1995.

- ↑ a b Luis Mitxelena: Diccionario General Vasco - Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia X Jad-Kop. Euskaltzaindia, Bilbao 1997.