Real Academia Española

The Real Academia Española [ reˈal akaˈðemja espaˈɲola ] ("Royal Spanish Academy") is the main institution for the maintenance of the Spanish language . It was founded in 1713 and publishes several dictionaries , a grammar and an orthographic rulebook and important sources on the history of the Spanish language. Your specifications are binding in school teaching and official use in Spain and the Spanish-speaking countries of America . In colloquial language it is often called Real Academia de la Lengua ("Royal Academy of Language") with or without the addition Española or la RAE ("the RAE").

Role models and founding

On August 3, 1713, a group of scholars met in the house of the Marquis of Villena in Madrid who felt it was a shame that there had been no dictionary for the Spanish language (in fact, Covarrubias had published the first monolingual dictionary a century earlier). Her role models for founding an academy were the Accademia della Crusca in Florence and the Académie Française in Paris. In Florence in 1580 a group of friends had started work on an Italian dictionary. The Vocabulario degli Accademici della Crusca was based on the vocabulary of Dante , Petrarch and Boccaccio , which the dictionary makers considered the high point of the Italian language, expanded by some modern writers. It was first published in 1612 and, in a greatly expanded, third edition, it was last published in 1691. In France, the Académie Française was formed in 1634 under the protection of Cardinal Richelieu . Her tasks included the creation of a dictionary, grammar, rhetoric and poetics of French . Your dictionary ( Dictionnaire ) was published in 1694 - after 60 years - and the alphabetical order was only introduced here with the second edition of 1718.

In analogy to the Académie Française , the founders named their Spanish learned society Academia Española . They requested protection from King Philip V without making any further claims. The king granted it the following year - on October 3, 1714 - and since then it has been allowed to call itself Real Academia Española ("Royal Spanish Academy").

Dictionaries

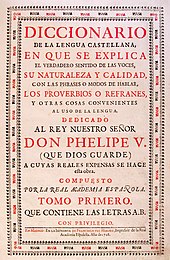

After the death of the poet Calderón de la Barca (1600–1681), the Spanish language went through a period of weakness. The founders of the academy regarded a dictionary as a means of regeneration. The idea behind this was that languages, like organisms, go through a youth, a mature age and a period of decay. In order to stop this decline, it was necessary to fix the best use of language from the maturity of the language ( fijar ) . After thirteen years, the Academy published the first volume of the Diccionario de la lengua castellana (“Castilian” in this context means something like “Spanish”) in 1726 ; after another thirteen years she completed the work in 1739 with the sixth volume. The work is known as Diccionario de Autoridades because, following the Italian model, each entry was given a quotation from literature - an "authority". The Diccionario de Autoridades was the most modern dictionary in the world in its time because it followed a descriptive approach in practice (see below: Self-understanding). It went beyond the vocabulary of a region: the Italian dictionary was limited to the Florentine vocabulary, the French equivalent to the Paris region . The Spanish dictionary, on the other hand, contained not only the literary vocabulary but also terms from colloquial language, from the provinces and even from the rogue language ( germanía ) . Even some Americanisms, words from the vocabulary of the Spanish-speaking countries in America, appeared here.

In 1770 the Academy tried to bring out a revised version of the Diccionario de Autoridades , but no more than a first volume was published. Instead, a Diccionario de la lengua castellana appeared in 1780 in a single volume that was easy to handle but lacked the evidence. This short version has become the Academy's actual dictionary under the short title Diccionario de la lengua española ; it is often called Diccionario común for short . This “ordinary dictionary” does not claim to be able to identify every word that occurs in the Spanish language.

Since then, the task of bringing out a historical dictionary has remained a task of the academy that has been demanded again and again and has not yet been completed. This Diccionario histórico de la lengua española is supposed to document the history of every word that occurs in Spanish from its first reference to its last appearance. The academy began work in 1914 and published two volumes in 1933/36, ranging from A to CE, by the time of the Civil War . The books that had already been printed were burned in a bombing raid in the autumn of 1936. After the war it was decided to start over and publish a dictionary that would even surpass the Oxford English Dictionary . The work began in 1947, the first fascicle was released in 1960, and since then the other fascicles have appeared in very slow succession. The historical dictionary is based on a corpus of 52 million words and should contain 170,000 entries when it is completed. Spanish is thus the only world-class European language for which no historical dictionary is available that would be comparable with the Oxford English Dictionary for English, with the Grimm dictionary for German, with the Dictionnaire historique de la langue française for French or also with the Diccionari català-valencià-balear for Catalan . The only competing company, which is limited in the choice of words, is the Diccionario de construcción y régimen de la lengua castellana by the Colombian Rufino José Cuervo .

In 1927 the Academy also published a Diccionario manual e ilustrado , which included words that were not yet suitable for the Academy dictionary for various reasons: be it because of their foreign language origin or because they were too new to be able to estimate whether they would stick to the Spanish vocabulary. This dictionary, which is more tailored to the general public, was last published in 1989. A micro-dictionary with 22,000 entries is planned for 2015 - based on the model of the Oxford dictionary.

Self-image: "Cleans, sets and gives shine"

In 1715 the statutes were published, a seal showing a melting pot in the fire and the motto Limpia, fija y da esplendor ("cleans, determines and gives shine") determined. This motto suggests that the academy, based on the French model, represents a normative or prescriptive self-image, i.e. wants to prescribe what is good use of language. The linguist Álvarez de Miranda has pointed out, however, that the Academy has chosen an astonishingly modern, namely descriptive, approach in practice from the outset. On the basis of a collection of texts , it was recorded which words were in use in Spanish and these were added to the dictionary. Even if the academy made evaluations to the extent that it designated individual words as "vulgar" or "low" (today the comment would be "colloquial"), these words were listed - unlike in France, for example - so that the users themselves could decide for or against their use. Only “indecent” words (voces indecentes) and proper names were not recorded.

The Academy Dictionary has remained the benchmark for Spanish language dictionaries for nearly 300 years. In the 18th century the only competing work was the Diccionario castellano by Esteban Terreros , a delicate undertaking since the authors were Jesuits who had been expelled from Spain in 1773. In the 19th century, only adaptations or pirated copies of the Academy dictionary appeared, mostly combined with a foreword in which the Academy was insulted for its allegedly bad work. What is remarkable, however, is the dictionary that Vicente Salvá published in Paris in 1846. Although he also started from the Academy dictionary, which he had carefully revised and expanded. His dictionary was primarily intended for the American market. Even María Moliner , who in 1966/67 published a much-acclaimed and famous dictionary, had developed it on the basis of the Academy dictionary. It was not until 1999 that a large Spanish dictionary appeared independently of the academy, the Diccionario del español actual under the direction of Manuel Seco , which could compete with the academy dictionary in every respect. It had been completely redrafted on the basis of a corpus of text, 70 percent of which was based on newspapers and magazines, 25 percent on books not only of a fictional nature and 5 percent on catalogs, brochures, leaflets, etc. This was the first time that a descriptive dictionary of the Spanish language, working with documents, was realized, the result of which was very different from the academy dictionary. Ironically, the author of the academy's most serious rival to date, Manuel Seco, is himself a member of the academy.

Grammar, spelling and source editions

The Academy's statutes also provided for the publication of a grammar, poetics and history of the Spanish language. However, another problem turned out to be urgent: the reform of the spelling . It developed in the 13th century without being adapted to the pronunciation that has changed since then. With the Diccionario de Autoridades , the academy began to standardize spelling. In 1741 it published its first set of rules - the Ortographía - but the reform was not completed until the eighth edition of 1815. Thanks to this work, the typeface in Spanish has remained much closer to pronunciation than, for example, in French or English. In 1844 the spelling of the Royal Academy was made compulsory in Spanish schools; the Spanish-speaking states of America joined over the years (most recently Chile in 1927). The spelling is continuously being reformed, most recently in 2000 and 2010. For example, since then the letter “ y ” may not only be called i griega , but also ye ; a word like solo no longer has an accent mark .

The first grammar of the Spanish language was written by Antonio de Nebrija in 1492 . The Royal Academy published its first grammar in 1771, but fell far short of the standard it had set with its dictionary and spelling. The grammar was reprinted in the 1796 version without changes until 1854. In the 19th century , the Venezuelan Andrés Bello - a corresponding member of the Academy - stood out with his work on Spanish grammar. In 1917 and 1924 the grammar of the Royal Academy was revised more, but eventually it became clear that it had to be completely rewritten. This task was prepared with the Esbozo de una nueva Gramática (“Draft for a new grammar”) by Salvador Fernández Ramirez and Samuel Gili Gaya in 1973, which put the phonology and morphology of the Spanish language on a new basis. The new grammar was finally published starting in 2009. According to the current director of the academy, José Manuel Blecua , the task remains to harmonize the dictionary, spelling and grammar.

The tasks of the academy also include the publication of important works from the history of Spanish language, starting in 1780 with a splendid edition of the Quixote in four volumes. Since then, the works of Cervantes have been repeatedly reissued by the Academy. After the Fuero Juzgo - a collection of laws from 1241 under Ferdinand III - in the year of the liberation from French rule in 1815 . which ultimately goes back to the Visigoths - had appeared, the academy was no longer active in the field of source editing for decades. It was not until 1890 that she published the plays by Lope de Vega in 15 large volumes, which also contain a biography . The anthology of Hispanic American poets in four volumes, published between 1893 and 1895, met with a great response in South America . Numerous other editions followed in the 20th century, such as the large study edition of the Cantar de Mio Cid - the heroic epic from around 1200, which is considered the first Spanish poetry - or the facsimile edition of the Libro de buen amor from 1330.

The way the academy works

With his privilege of 1714, the king had set the number of academics at 24. Among them were aristocrats , knights of military orders, courtiers and high-ranking clergy . Thanks to the history of its origins, the academy had close ties to the court, and since 1723 it was also subsidized by the state. At that time, Philip V granted her for the first time 60,000 reales from the tobacco tax to finance the printing costs of the dictionary.

During the period of French rule between 1808 and 1814, the academy almost ceased its work. But even after the liberation it recovered only slowly under the reign of Ferdinand VII (1814–1833): numerous seats remained vacant, and the academy had difficulties financing a new edition of the dictionary. According to Rafael Lapesa, the academy's comparatively poor performance in this century is - apart from the political reasons - also related to the fact that the academics showed little inclination towards collaborative work and preferred to pursue their own projects. During this time, the Real Academia Española changed from a learned society to an academy whose members represent the elite of Spanish literature. But also outstanding Spaniards without reference to literature or lexicography were honored with a seat in the academy: One example is the later Nobel Prize winner for medicine , Santiago Ramón y Cajal , who was elected to the academy in 1905 but never took part in its work.

In 1848 the Academy received new statutes: The number of members was increased from 24 to 36, vacant seats had to be filled again within two months. For the first time, commissions for dictionary, grammar, spelling, etc. were set up, in which the actual work is still done today. Academics were given the right to purchase and read banned books. It was also stipulated that the Academy would never comment on the quality of literary works, poems, etc. unless specifically requested to do so by the Crown. Since then, the statutes have been revised several times and supplemented by rules of procedure. For the historical dictionary (Diccionario histórico de la lengua española) , a lexicographical seminar was set up at the Academy for the first time in 1947, which is financed by the state, and thus the work was placed in the hands of full-time linguists. Foreign Hispanists are included as corresponding members. The traditionally strong German Hispanic studies was and is - beginning in 1868 with Adolf Friedrich von Schack - integrated in this way. Today the academy has 46 members, the so-called "academics". Their chairs are marked with the upper and lower case letters of the alphabet, they are called academico de número - a bit misleading for German ears . To be accepted, an academic must first die. In a secret ballot, the colleagues then choose the successor.

In 1784, María Isidra de Guzmán y la Cerda was the first woman to be accepted - probably under pressure from the court - not as a regular member, but as an honorary member. Little is known about the then 17-year-old; it is only mentioned once in the third edition of the Diccionario . She seems to have stopped working after moving to Granada as Marquesa from Guadalcázar. So there would have been a precedent when the respected writer Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda applied for inclusion in 1853 . On this occasion, in a secret ballot, the academics decided with 14 to 6 votes not to admit women. At the beginning of the 20th century women again tried to get accepted into the academy: 1912 Emilia Pardo Bazán , 1928 Blanca de los Ríos , both authors were rejected. In 1972, the rejection of the lexicographer María Moliner , who had developed an original and successful own dictionary on the basis of the Academy dictionary, caused a lot of stir . It was not until 1978 - after almost two centuries - that a woman, the writer Carmen Conde , was accepted again. The other two candidates for her seat were women too, so the Academy would have had no choice. In 2013 there are six female academics.

The main task of the academy remains the revision of the ordinary dictionary. It is notorious that once a definition is recorded, it stays there until it just looks weird. The 19th edition from 1970 defined “kissing” ( besar ) still as “touching an object with the lips as a sign of love, friendship or admiration, whereby the lips are gently drawn together and apart”. This definition goes back in a little changed form to the Diccionario de Autoridades of 1726. The preparation of a new edition was always entrusted to one or two academics until 1970; only since then has a group of linguists been continuously working on the dictionary. 14 commissions have been set up for specialist vocabulary and numerous specialists have been appointed to the academy.

Originally the academy was based in the house of its founder, the Marqués de Villena; after his death the members met in various other houses. In 1894 the academy moved into its current building: the building site was donated by the Krone, and the building costs were two million pesetas . Today it is a representative building of Madrid with its imposing front, the exquisite furnishings, the location near Prado and the monastery church of San Jerónimo el Real . The library comprises 250,000 volumes, but also more than 2000 manuscripts by writers such as Lope de Vega and Pablo Neruda . The building also houses a splendidly painted lecture hall, the lexicographical seminar, and other rooms for the various commissions. Well known to the Spanish public is the large, oval table in the plenary room where academics gather for their meetings.

The academics meet for their plenary sessions on Thursday evenings at half past seven. Here new words or new meanings can be suggested and discussed for inclusion in the dictionary. Before a new entry is finally added, it is waited five years to see whether the use of the word has stabilized. The word is checked by linguists at the academy, sent to colleagues from the Latin American academies for comment, and finally a draft is written for the entry, which is finally approved in plenary. The meeting ends punctually at eight thirty.

Lexicographical work has changed due to information technology. Two databases have been set up since 1995. The Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual contains 200 million entries that are intended to represent a representative sample of contemporary Spanish since 1975. Oral statements and samples from Spanish-speaking countries in America were also taken into account. Models are the British database projects Bank of English and British National Corpus . In the Corpus Diacrónico del Español historical texts from the beginnings of the Spanish language to 1974 are recorded. This database forms the working basis for the historical dictionary. In 1995 an edition of the Academy dictionary appeared on CD-ROM for the first time . The dictionary, which is now available online, was updated five times between 2001 and 2013.

In 2014, the 23rd edition appeared on paper, and the academy's secretary Dario Villanueva doesn't think it will be the last. Inquiries about cases of doubt about the Spanish language can be sent to the Español al Día department - now also via Twitter . The budget amounts to 7.6 million euros per year, of which 1.9 million come from the state. The rest comes from the income from book sales and donations.

Relations with Latin America

In Latin America as early as the mid-19th century - for example in Colombia , Venezuela or Argentina - linguists were concerned with the Spanish language. The Real Academia Española had a pacemaker role in the founding of corresponding national academies in South America by first appointing individual South American personalities as corresponding members and then asking them to look for colleagues. The first academy was founded in Colombia in 1871, followed quickly by academies in Ecuador , Mexico , El Salvador , Venezuela, Chile , Peru and Guatemala by 1887 . Eight other academies were established between 1922 and 1949, as well as an academy in the Philippines in 1924 , in Puerto Rico in 1955 and in North America in 1973 . Only the Argentine and Uruguayan academies were created independently of the Real Academia , even if they have good relationships with it. Examples are:

- Academia Mexicana de la Lengua

- Academia Argentina de Letras

- Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española

- Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española

In 1952 the first Congress of the Spanish Language Academies was held in Mexico, and has since met every four years. At the 1960 Congress in Bogotá , the Society of Spanish Language Academies was founded and has been based in Madrid since 1965. The cooperation was put on a new basis with the "International Congress for Spanish Language" at the 1992 World Exhibition in Seville . One consequence is that the Academy is involved in updating the “Dictionary of Americanisms”.

All entries in the academy dictionary are also reviewed by American Spanish speakers. This close cooperation and the adoption of the spelling rules have so far prevented the Spanish language from splitting up in a similar way to what can be observed for Portuguese in Brazil and Portugal .

Relationship to the other languages of Spain

In the 19th century the problem of nationalism became acute in Catalonia , the Basque Country and Galicia , which also led to a renaissance of the associated languages. During the reign of the dictator Primo de Rivera in 1926 , the king ordered that additional seats be established in the academy for these languages, and in fact academics were appointed in Catalan , Valencian , Mallorcan , Galician and Basque at that time . In 1930, however, the Academy decided to phase out these seats and since then the Royal Academy has been solely responsible for the Spanish language (Castilian). The other languages of Spain are taken care of by other institutions: Catalan from the very active Secció Filològica of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans in Barcelona , Basque from the Real Academia de la Lengua Vasca - Euskaltzaindia in Bilbao and Galician from the Real Academia Galega in A Coruña .

Academic publications

The first print and the current edition (selection) are listed.

"The" Academy Dictionary:

- Diccionario de la lengua castellana en que se explica el verdadero sentido de las voces, su naturalzea y calidad, con las frases o modos de hablar, los proverbios of refranes, y otras cosas convenientes al uso de la lengua. Dedicado al Rey Nuestro Señor Don Phelipe V. (que Dios guarde), a cuyas reales expensas se hace esta obra. Compuesta por la Real Academia Española. 6 volumes, Madrid 1726–1739. (Vol. 1 and 2 printed by Francisco del Hierro, Volume 3 by his widow, Volumes 4-6 by his heirs). Commonly known as the Diccionario de Autoridades .

- Facsimile edition in three volumes by Gredos, Madrid 1964

- Diccionario de la lengua castellana compuesto por la Real Academia Española, reducido á un tomo para su mas fácil uso . Printed by Joaquín Ibarra, Madrid 1780. Known as Diccionario de la lengua española de la Real Academia Española .

- Diccionario de la lengua española . 23rd edition. Espasa, Madrid 2014. The definitive dictionary of the Spanish language, abbreviated: DRAE .

Historical Dictionary:

- Diccionario histórico de la lengua española. Volume 1: A , Volume 2: B – Cevilla , Academia Española, Madrid 1933/1936.

- Diccionario histórico de la lengua española. Real Academia Española, Madrid 1972.

Other dictionaries:

- Diccionario manual e ilustrado. 1927, last 4th edition, Espasa Calpe, Madrid 1989.

- Diccionario escolar de la Real Academia Española. 1996, last 2nd edition. Espasa Calpe, Madrid 2001. Dictionary with 33,000 entries for school use

- Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. 2nd edition, Santillana, Madrid 2005.

- Diccionario de americanismos. Santillana, Madrid 2010. With the participation of the Academy

- Manuel Seco, Olimpia Andrés, Gabino Ramos: Diccionario fraseológico documentado del español actual. Locuciones y modismos españoles. Aguilar lexicografía, Madrid 2004, ISBN 84-294-7674-1 .

Spelling, orthography:

- Ortographía española. Compuesta, y ordenada por la Real Academia Española, que la dedica al Rey N [uestro] Señor. Real Academia Española, Madrid 1741.

- Prontuario de ortografía española. EDAF, Madrid 2000. A brief outline of the spelling for school use

- Ortografía de la lengua española. Espasa, Madrid 2011.

Grammar:

- Gramática de la lengua castellana, compuesta por la Real Academia Española. Printed by Joachin de Ibarra, Madrid 1771.

- Nueva grámatica de la lengua española. 3 volumes. Espasa, Madrid 2009–2011.

Series of publications:

- Boletín de la Real Academia Española. Since 1914. Bulletin of the Academy

- Anejos del Boletín de la Real Academia Española. Since 1959. Includes monographs on Hispanic topics.

Source editions (small selection):

- Miguel de Cervantes : Quixote . 4 volumes. Printed by Joaquín Ibarra, Madrid 1780.

- Fuero Juzgo en latin y castellano . Printed by Ibarra, Madrid 1815.

- Obras de Lope de Vega. 15 volumes. 1890-1930.

- Antología de poetas hispanoamericanos . 1893-95.

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal (Ed.): Cantar de Mio Cid . Texto, gramática y vocabulario. 1908-1911.

- El libro de Buen Amor. Heraclio Fournier, Vitoria 1974. Reproduction of the Codex Gayoso from 1389

literature

- Alonso Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. Espasa Calpe, Madrid 1999, ISBN 84-239-9185-7 .

- Rafael Lapesa : La Real Academia Española. Pasado, realidad presente y futuro. In: Boletín de la Real Academia Española. Volume 67, Issue 242 (1987), pp. 329-346.

- Günther Haensch: Spanish Lexicography. In: Franz Josef Hausmann, Oskar Reichmann, Herbert Ernst Wiegand, Ladislav Zgusta (eds.): Dictionaries, Dictionaries, Dictionnaires. An international handbook on lexicography. Second part of the volume. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1990, pp. 1738–1767.

Members

Honorary President of the Academy is the King of Spain Juan Carlos I .

The current académicos de número are, in the order of their vocation (in brackets the lower or upper case letter to which they are assigned).

former members

- Dámaso Alonso

- Pio Baroja

- José Luis Borau

- Camilo José Cela

- Miguel Delibes

- Leandro Fernández de Moratín

- Antonio Machado

- Julián Marías

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal

- Benito Pérez Galdós

- Manuel José Quintana

- José Luis Sampedro

See also

- Spanish language

- Spanish grammar

- Diccionario de la lengua española de la Real Academia Española

- List of Spanish language academies

Web links

- Official website of the Real Academia Española (Spanish)

- List of editions and dates of the Spanish grammars published by the Real Academia Española (RAE) PDF

Individual evidence

- ^ Alonso Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española . Espasa Calpe, Madrid 1999, ISBN 84-239-9185-7 , p. 33.

- ^ A b Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 26.

- ↑ Pedro Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno . Trea, Gijón 2011, ISBN 978-84-9704-512-4 , p. 18.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Victor Núñez Jaime: Entramos en la casa de las palabras . In: El país semanal , February 28, 2013.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. …, P. 334. In the Historia de la Real Academia Española . In: Diccionario de la lengua castellana. Volume 1, Madrid 1726, p. Xi, reads: Los Franceses, Italianos, Ingleses y Portugueses han enriquecido sus Patrias e Idiomas con perfectíssimos Diccionarios, y nosotros hemos vivido con la gloria de ser los primeros y con el sonrojo de no ser los mejores. ( sonrojo means "blush")

- ↑ Sebastián de Covarrubias Orozco: Tesoro de la lengua castellana, o española […] . Madrid 1611.

- ↑ a b Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., p. 21.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 28.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 333.

- ↑ Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., p. 22.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 369 f.

- ↑ a b Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., p. 18 f.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 334.

- ↑ In detail Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., pp. 21-25.

- ↑ Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., p. 23.

- ↑ Diccionario de lengua castellana compuesto por la Real Academia Española . 2nd corrected and enlarged edition. Volume 1: A-B . Printed by Joachin Ibarra, Madrid 1770.

- ↑ Diccionario de la lengua castellana compuesto por la Real Academia Española, reducido á un tomo para su mas fácil uso . Printed by Joaquín Ibarra, Madrid 1780.

- ↑ Diccionario histórico de la lengua española . Volume 1: A , Volume 2: B – Cevilla , Academia Española, Madrid 1933/1936.

- ↑ Diccionario histórico de la lengua española . Real Academia Española, Madrid 1972 ...

- ↑ Dictionnaire historique de la langue française . Le Robert, Paris 1992.

- ^ Antoni Ma. Alcover and Francesc de B. Moll: Diccionari català-valencià-balear . 10 volumes. Palma de Mallorca 1962–1968.

- ↑ Rufino José Cuervo: Diccionario de construction y régimen de la lengua castellana . Volume 1: A-B. Paris 1886; Volume 2: C-D. Paris 1893; all 8 volumes: A – Z. Instituto Caro y Cuervo, Bogotá 1994.

- ^ Diccionario manual e ilustrado , 1927.

- ↑ Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., p. 31.

- ^ Haensch: Spanish Lexicography ..., p. 1743.

- ^ Diccionario castellano con las voces de ciencias y artes y sus correspondientes en las tres lenguas francesa, latina e italiana . 4 volumes. Printed by the widow of Ibarra, Sons and Company, Madrid 1786–1793.

- ↑ Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., pp. 55–87.

- ↑ Nuevo diccionario de la lengua castellana, que comprende la última edición íntegra, muy rectificada y mejorada, del publicado por la Academia Española, y unas veinte y seis mil voces, acepciones, frases y locuciones, entre ellas muchas americanas . Paris 1846.

- ↑ Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., pp. 89–118.

- ^ A b María Moliner: Diccionario de uso del Español . 2 volumes. Gredos, Madrid 1966/67.

- ↑ Manuel Seco, Olimpia Andrés and Gabino Ramos: Diccionario del español actual . 2 volumes. Aguilar, Madrid 1999.

- ↑ Álvarez de Miranda: Los diccionarios del español moderno. ..., pp. 151-163.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 36.

- ↑ Ortographía española. Compuesta, y ordenada por la Real Academia Española, que la dedica al Rey N [uestro] Señor . Real Academia Española, Madrid 1741.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 335.

- ↑ Prontuario de ortografía de la lengua castellana, dispuesto por Real Orden para el uso de las escuelas públicas por la Real Academia Española con arreglo al sistema adoptado en la novena edición de su Diccionario . 1844.

- ^ Nebrija: Gramática castellana .

- ↑ Gramática de la lengua castellana, compuesta por la Real Academia Española . Printed by Joachin de Ibarra, Madrid 1771.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 335 f.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 337.

- ↑ Esbozo de una Nueva Gramática de la lengua española . Espasa Calpe, Madrid 1973.

- ↑ Nueva grámatica de la lengua española . 3 volumes. Espasa, Madrid 2009–2011.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., pp. 534-545.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., pp. 382-385.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 28.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 29 and 31.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 40.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 451.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 37.

- ^ Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 337.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 158 f.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 38 f.

- ↑ Seminario de Lexicografía

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 328.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 485 f.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 488 f.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., pp. 490-495.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 497.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 499.

- ↑ quoted from Lapesa: La Real Academia Española. …, P. 341: tocar alguna cosa con los labios contrayéndolos y dilatándolos suavemente, en señal de amor, amistad, o reverencia .

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 53.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 55.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., pp. 573-575.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 374.

- ↑ @RAEinforma

- ↑ Status: 2013

- ^ Congreso de Academias de la Lengua Española

- ^ Congreso Internacional de la Lengua Española

- ↑ Diccionario de Americanismos . Santillana, Madrid 2010.

- ^ Zamora Vicente: La Real Academia Española. ..., p. 41 f. and 290-309.

- ^ Günther Haensch: Catalan Lexicography . In: Franz Josef Hausmann, Oskar Reichmann, Herbert Ernst Wiegand and Ladislav Zgusta (eds.): Dictionaries, Dictionaries, Dictionnaires. An international handbook on lexicography . Second part of the volume. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1990, pp. 1770–1788.

Coordinates: 40 ° 24 '54.1 " N , 3 ° 41' 27.3" W.