Light art

The light art is next to the painting, sculpture or photography an autonomous art form in the parent categories of today sculpture and installation can be found. Contemporary light artists work primarily with artificial light as a light source. Of light art can only be spoken if the use of light sources aesthetic serving purposes. As a rule, this does not apply to installations whose purpose is merely to make objects visible in the dark through lighting, or which have a profane character (such as the colored lights in traffic lights), as well as commercial neon signs that do not fit the framework of conventional designs blows up. Most works of light art require the extensive absence of natural (day) light and competing artificial light sources in order to develop their full effectiveness.

Major works of light art

The main works of light art include the light-space modulator (1920–1930) created by Lázló Moholy-Nagy and the Diagonale from May 25 (1963), a light strip with a yellow fluorescent tube by the American Dan Flavin . Her work groups Ólafur Elíasson , Brigitte Kowanz , Mischa Kuball and Christina Kubisch are counted among the younger representatives of this art movement.

Types of light art through the ages

In the broadest sense of the term, those people who specifically used light effects for aesthetic purposes were "light artists". Such effects could be achieved with the help of fire, candlelight or black powder (see fireworks ), but also by coloring the daylight through the design of windows.

In a narrower meaning of the term, one can speak of light art only since the 19th century, since since then there has been the possibility of using advanced lighting techniques for artistic purposes.

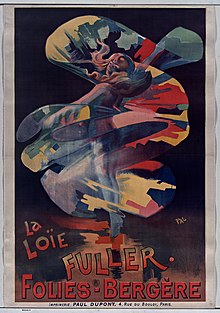

Illuminated dance

In 1892, the American dancer Loïe Fuller made her debut at the Folies Bergère in Paris as a living light sculpture with a dance that seemed to celebrate the industrial revolution as an aesthetic event. Wrapped in an oversized white cloak made of crepe de chine , the range of motion of the arms extended into the fabric with aluminum rods and illuminated by the sharp beam of an arc lamp embedded in the stage floor, the audience was presented with a scenography of flowing and swirling webs of fabric, a transforming structure of light .

“Je sculpte de la lumière” - “I shape light”, was the programmatic title of the dancer for her work, underlining the demand for an abstract art that emerges less as a direct expression of social reality, but rather as a claim to an aesthetic counter-world.

Light as an artistic signal

In 1928, Lázló Moholy-Nagy summarized his experiences with a developing photography with which light was perceived as a medium for the first time: “The light-sensitive layer, plate or paper - is a blank sheet of paper that can be written on with light like that Painter with his tools. ” But the Hungarian-born artist, who started working at the Bauhaus in Dessau in 1923 , was less interested in photography as a medium than in a“ new way of seeing ”, an art that comes from the machine.

The driving element for Moholy-Nagy was the demand for a technical art, a machine art at the height of the social upheavals at the beginning of the 20th century.

Moholy-Nagy has been developing a light-space modulator since 1920 , which he did not show until 1930 at the exhibition of the Deutscher Werkbund in Paris. The model consists of a cubic box with a circular opening (stage opening) on the front. Around the opening, on the back of the plate, a number of yellow, green, blue, red and white colored electric light bulbs are mounted. Inside the box, parallel to the front, there is a second plate with a circular opening, which also has electric light bulbs of different colors. Individual light bulbs light up in different places based on a predetermined plan. They illuminate a continuously moving mechanism, which is partly made of transparent and partly openwork materials in order to achieve the most linear shadow and color projections possible on the walls of a darkened room.

Fascist productions

The political changes in National Socialist Germany had a destructive effect on Moholy-Nagy's experiments and thus also on the visions and utopias of the artistic avant-garde . The cultic dimension of light, which also appears in Moholy-Nagy , was abused by the National Socialists as a political instrument. With the use of flak headlights for the propaganda marches of the National Socialists in Nuremberg, Berlin and other German cities, Albert Speer not only demonstrated his penchant for the pathetic, but also saw himself as the high priest of the calculated use of light and its emphatic effect on the masses. From the perspective of anti-fascists, its monumental appearance turned one of the oldest notions of humanity into its opposite, namely that according to which light brings salvation from the perspective of anti-fascists .

Programmed plays of light

In the second half of the 20th century, the radical concretization of light was on the agenda. In this way, an attempt was made in a second attempt to tie in with Moholy-Nagy's Bauhaus experiments and rediscover artificial light as an artistic material.

The artist Nicolas Schöffer , also a Hungarian who, like Moholy-Nagy, adhered to the utopia of total urban aestheticization, had been developing spatial-dynamic light architectures in Paris since 1948 . The aim of his activity was a cybernetic city, a city that reacts to the times of day, temperatures and weather with light and movement. This largely unbroken, future-oriented and technically euphoric dimension also determined the works of the Düsseldorf artist group ZERO , to which u. a. Heinz Mack , Otto Piene and Günther Uecker belonged.

Piene, the most efficient organizer and enthusiastic theoretician of this group, first developed true light ballets and light plays with hand lamps, then increasingly with mechanical, electrically programmed structures.

Neon tube art

At the same time there was a tendency in the works of American artists to concentrate on 'pure' light and its propagation in space. In 1963 the first icon was created , with which the American Dan Flavin has justified his entire work to this day: The Diagonale of May 25 , a standardized industrial product, a light strip with a yellow fluorescent tube.

In contrast to traditional plastic and sculpture, which is modeled with light from the outside, with Flavin the light penetrates from inside to outside. The goal of light is not a body, but space. After still life-like individual installations, Flavin quickly developed a repertoire of light barriers and light corridors and thus became a pioneer for a large number of the artists who followed him and who are concerned with the diffusion of light in space. Its exclusively industrially standardized light tubes are not subordinate to any economic or social purpose, but to the laws of space. Walls, ceiling and floor are their bearers, the architecture is the dialogue partner.

Desubjectified profanity on the one hand and spiritually apparent sensuality characterize the work of another American artist: James Turrell . Turrell presents light in its physical facticity, in its metaphysical effect. Turrell is an artist who creates light spaces that appear dimensionless and limitless.

Together with the works of Dan Flavin, but also Robert Irwin or Douglas Wheeler from around 1970, James Turrell's light installations are self-referential , the investigation of light as a material with its physical-optical properties and its temporal-spatial effect on the Viewer.

This demonstration of optical borderline phenomena has been tried out in parallel by a number of artists with different individual handwritings and has been continued in public space up to our time. There is always an alternation between the demonstrative demonstration of the fluorescent tubes and the spherical immateriality of indirectly generated light; between architecture-related accentuation through luminous lines and their dematerialization into an inconceivable light space.

In addition to abstract light art, a second tradition of dealing with light as an artistic medium has developed almost at the same time. It has its roots in illuminated advertising . In 1879 it was the development of the commercial incandescent lamp , as a result of which the cities were covered with luminous advertising. From 1912 onwards, the neon advertising sign, the "living flame", as the neon tube is called in America and which is now used en masse , took its place the tracing of symbolic advertising emblems or lettering is used.

While this fashion suffered a slump at the beginning of the 1970s, artists, as part of their very different artistic concepts, discovered the thin, malleable fluorescent tube as the ideal starting material for creating light structures from individual words, sentences or entire images. François Morellet , Keith Sonnier and Maurizio Nannucci stand for the former, while Joseph Kosuth , Mario Merz and Bruce Nauman draw for the less abstract use of the fluorescent tube .

In 1968 Mario Merz asked in blue neon letters what to do: “Che fare?” Later he used this lamp in numerous variants to arrange a sequence of numbers to calculate spirals by the medieval Italian mathematician and philosopher Fibonacci to illustrate a procedural order of natural and spiritual Energy.

The fact that the power of fascination emanating from the colorful fluorescent tubes can be dangerous for artistic work is also a topic of art criticism at this time. It is therefore repeatedly pointed out that these materials can only be integrated into the artistic process as long as the fascination of the material does not override the aesthetic discourse, as long as the luminous color body is legitimized by a convincing artistic concept and not as a decorative end in itself rotten. A more recent example of controversial fluorescent tube art is the memorial to Georg Elser in Munich, Silke Wagner's work “ November 8, 1939 ”.

See also: Museum of Neon Art , Iconography

Messages on displays

At this point, the interest of art critics quickly turns to those artists whose works focus on the content messages. In America, the artist Jenny Holzer first made a name for herself in 1982 with her work of illuminated letters. In the enclosed public space, it confuses unprepared viewers and passers-by with messages that run on the electronic display board in Time Square in New York. Where everything is crowded and advertisements, news and event notices are jumbled, the artist suddenly confronts readers with truisms from an information board that they cannot classify. Such actions are considered socially committed, politically oriented light art.

Projections

Christian Boltanski is an artist who has advanced to become the most paradigmatic producer of traces thanks to the term “securing evidence” coined by the critic Günter Metken . Showcases with childhood documents were followed by glowing giant jumping jacks , projections and shadow games of simple wire figures, which, as light and shadow structures, as nightmares of their own inwardness, as grimaces of a society traumatized by the Holocaust, drive their demonic mischief on the walls of the galleries and museums.

The artist Nan Hoover is one of the pioneers of light art using the means of film, video and performance art . Her main theme is the human body in its being between light and shadow. In their works, light and shadow cause a transformed appearance of a former reality and thus the dissolution of what was previously familiar. As every object placed in the light creates shadows, so does the human body. The artist thus refers to the unifying reality of shadow and body in the sense of Plato's allegory of the cave .

In the 1980s, light projection became the dominant medium in light art. The Düsseldorf artist Mischa Kuball uses projectors, mostly gyro projectors, which allow him to constantly change the light emission or motif. His artistic work is always adapted to the location. For example, he traced the shape of a former Gauleiter bunker from the 1930s on the street with light and in 1998 at the São Paulo Biennale offered Brazilian citizens lamps in the style of timeless design classics, in exchange for their personal lamps as a concentrate of the private to create two luminous surfaces together in the museum.

The most spectacular, because extremely simple light work by this artist is considered to be “refraction house”, a small synagogue in Stommeln on the Lower Rhine, barely visible from the main street, nested and hidden. It is flooded from the inside with light that seems to scream out of the windows and the lunette , and pushes the walls of the synagogue, the outer stone into the darkness, dematerializes all bystanders and puts them in a blazing light. “Yesterday and today are related,” writes Armin Second in the catalog about this unsentimental memory work.

The works of the last-named artists, who represent a whole range of other “projection artists” of their generation, thrive on the aesthetic impact of their medium. In contrast to the purists of the 1960s and 1970s, however, these artists primarily (as the word suggests) as an instrument of communication, of visual communication . It is used as a carrier of meaning and always refers to the semblance of its projective promise by making it clear that messages can always serve an ideology or a lie . These artists practice socially engaged art with the help of light as a medium.

LED light technology

With the development of lighting technology, new areas of application for light art projects are emerging, especially in public spaces. For example, building facades can be set in motion with pre-screened LED networks, for example at the Uniqa Tower in Vienna. The decisive factor in this development is that the light source , i.e. the light-emitting diode, not only emits light, but also provides imaging. One of the most interesting artistic concepts in the German-speaking area can be found in Munich in front of the Osram headquarters , where seven six-meter-high LED steles represent the platform for changing projects. Media and video artists such as Diana Thater , Bjørn Melhus or Harun Farocki have already developed reactive works for this in a site-specific manner.

Museums and permanent installations

Works of light art in German-speaking countries can be found in Unna (as a permanent exhibition in the Center for International Light Art ), in the eastern Ruhr area and in the Hellweg region (" Hellweg - a light path "). In the USA, the Museum of Neon Art is dedicated to light art.

Exhibitions and temporary projects

The color festival has been taking place at the Bauhaus Dessau since 1997, showing light-based installations and interventions. In 2011 and 2012 it is entitled “Instead of color: light”. From 2000 to 2011 the “Arbres en Lumieres” festival took place annually in Geneva and the Braunschweig “Lichtparcours” periodically. The Luminale in Frankfurt and the light routes in Lüdenscheid have been taking place since 2002 . The Internationale Lichttage Winterthur has been held in Winterthur every three years since 2004 . The projection biennale " Lichtsicht " has been taking place in Bad Rothenfelde since 2007 . In 2009 the Neulicht am See project was carried out in Hanover . In 2010 the first biennial for international light art took place under the motto “open light in private spaces” as part of the cultural capital Ruhr.2010 , based on the first biennale for light art Austria . In 2011 the luminous fluxes were realized for the first time in Koblenz. Since 2006 the light art festival "GLOW" (International Forum for Light Art and Architecture) has taken place annually in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. The Amsterdam Light Festival kicked off in Amsterdam in 2012 with a staging of the city icon “ Magere Brug ” by the internationally recognized Dutch light artist Titia Ex . In 2018 “ Hannover lights up ” started.

Curators

Overview of the curators who work repeatedly and regularly on the subject of light in contemporary art:

Soke Dinkla

- "Ruhrlights", exhibition in the Ruhr area, 2007, 2008, 2010

Bettina Pelz

- " Light Routes " (with Tom Groll), Festival in Lüdenscheid, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2010, 2013

- "GLOW" (with Tom Groll), Festival in Eindhoven, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009

- “Narracje”, Festival in Gdansk, 2009, 2010, 2011

- RUHR.2010 - Temporary interventions in Essen, Dortmund and Hagen, 2010

- " Lichtströmme " (with Tom Groll), Festival in Koblenz, 2011, 2012

- “Color Festival at the Bauhaus Dessau”, Festival in Dessau-Roßlau, 2011

- “Switch on Beijing” (co-curator), Festival in Beijing

- " Internationale Lichttage Winterthur ", festival in Winterthur

- “Lightmarks” (co-curator), Festival in Sønderborg, 2017

Manfred Schneckenburger

- "Lichtsicht", Festival in Bad Rothenfelde, 2009, 2011, 2013

Matthias Wagner K

- “Light and Seduction”, Center for International Light Art Unna, (with Sabine Schirdewahn), 2004

- "Light - The Magic of the Stage Space", Center for International Light Art Unna (with Sabine Schirdewahn), 2005

- "Light - Thinking Space and Staging", Center for International Light Art Unna, 2005

- " Hellweg - ein Lichtweg ", permanent light art interventions in the Hellweg region, since 2002

- " Biennale for International Light Art - open light in private spaces", Ruhr2010, Hellweg region

- "Angela Bulloch, Andreas Oldbod, Jun Yang", "LichtKunstRaum - Sankt Reinoldi", Ruhr2010, Dortmund

- “More light”, Goethe-Institut Budapest (with Róna Kopeczky), 2012/2013

Terms and valuations

In art, design, stage and architecture, the reflective use of daylight and artificial light is one of the fundamental aspects of artistic and creative practice, which is why no uniform linguistic terms that are linked to qualitative parameters have prevailed in common linguistic usage. An exception is “(architectural) lighting design” with the development of professional associations (including the “Professional Lighting Designers Association / PLDA” based in Gütersloh) and the development of new university study programs (including the Hildesheim University of Applied Sciences Lighting Design).

Promotion of light art

In 2002, an association of cities called " LUCI " (Lighting Urban Community International) was founded. The Italian word "luci" (German: "lights") is alluded to. One of the goals of the network is to create an urban identity by promoting light art, especially in the form of illuminations. “Festivals of Light”, which take place regularly, are an important instrument for reaching this goal.

Movies

- LIGHT ART. Three-part television series of 26 minutes by Marco Wilms. Producer: Christian Beetz. Germany 2006. Gebrüder Beetz Filmproduktion / ZDF / arte.

- “Light is what you see. Outstanding works of contemporary light art ”shows highlights of light art in three programs. With John Armleder, Angela Bulloch, Keith Sonnier and Peter Weibel.

Important artists

- Siegrun Appelt

- Waltraut Cooper

- Ólafur Elíasson

- Dan Flavin

- Juan Garaizabal

- Gerry Hofstetter

- Jenny Holzer

- Nan Hoover

- Rebecca Horn

- Kazuo Katase

- Brigitte Kowanz

- Mischa Kuball

- Heinz Mack

- Francesco Mariotti

- Mario Merz

- László Moholy-Nagy

- François Morellet

- Bruce Nauman

- Otto Piene

- Rosalie

- Nicolas Schöffer

- Keith Sonnier

- James Turrell

- Jan van Munster

- Marian Zazeela

- ZERO

- Victoria Coeln

literature

- Söke Dinkla, Center for International Light Art (Ed.): At the edge of light, in the midst of light . Wienand, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-87909-853-0 .

- Andrea Domesle: Luminous writing art: Holzer, Kosuth, Merz, Nannucci, Nauman . Reimer, Berlin 1998 (also dissertation (1995) at the University of Freiburg).

- Jeannine Fiedler, Hattula Moholy-Nagy: László Moholy-Nagy. Color in transparency. Photographic experiments in color. 1934-1946. (exhibition schedule: Bauhaus Archive, Museum of Design, Berlin, June 21 – September 4, 2006) . Ed .: Bauhaus Archive Berlin. Steidl, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-86521-293-1 .

- Anne Hoormann: Light plays. On the media reflection of the avant-garde in the Weimar Republic . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7705-3770-X .

- Brygida M. Ochaim, Claudia Balk: Variety dancers around 1900. From sensual intoxication to modern dance, an exhibition by the German Theater Museum in Munich October 23, 1998 to January 17, 1999 . Stroemfeld, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-87877-745-0 .

- Christoph Ribbat : Flickering modernity. The story of neon light . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-515-09890-8 .

- Wolfgang Schivelbusch : Light, appearance and delusion. Appearance of electric lighting in the 20th century . Ernst & Sohn, 1992, ISBN 3-433-02344-1 .

- Christian Schoen : Osram Seven Screens . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2011, ISBN 978-3-7757-2804-1 .

- Noemi Smolik: Jenny Holzer . In: Art Today . No. 9 . Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-462-02297-0 .

- Marga Taylor (Ed.): Dan Flavin - The Architecture of Light . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 1999, ISBN 3-7757-0910-X .

- Armin Second, Gerhard Dornseifer: refraction house, Mischa Kuball . Synagoge Stommeln, Kulturamt Pulheim, Pulheim 1994, ISBN 3-88375-199-5 .

- Matthias Wagner K: 1st Biennale for International Light Art - open light in private spaces . Revolver Publishing by VVV, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86895-102-8 .

- Matthias Wagner K, Sigrun Krauß (ed.): Hellweg-ein Lichtweg Light Art in Urban Spaces . Revolver Publishing by VVV, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-95763-237-1 .

- Robert Simon, Julia Otto (Ed.): Headlights Spotlights / Light Art in Germany in the 21st Century . Kerber Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-7356-0056-1 .

- Michael Schwarz (Ed.) Light and Space: Electric Light in 20th Century Art / Cologne: Wienand Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-87909-604-X

See also

- Exposure (architecture)

- Fireworks

- Light painting

- History of lighting

- Illumination (lighting)

- Bulbs

- Light guidance

- Lighting design

- Lighting technology

- Theater lighting

- Art in public space

Web links

- Siegrun Appelt, introduction to the concept "Slow Light"

- Waltraut Cooper, interview with the pioneer of light art

- LIFA website - Light in Fine Arts

- Official website of the Biennale for International Light Art 2010

- Official website of the Color Festival at the Bauhaus Dessau

- Official website of the network "Hellweg - ein Lichtweg"

- Official website of the International Light Days Winterthur

- Official website of Lichtrouten Lüdenscheid

- Official website of Lichtström Koblenz

- Official website of Luminale Frankfurt

- Official website GLOW Eindhoven, forum for light art and architecture.

- Gerry Hofstetter - Monuments of Switzerland Monuments of the World

- Center for International Light Art Unna

Individual evidence

- ↑ OSRAM Seven Screens or OSRAM Art Projects

- ↑ GLOW, Eindhoven 2009, Beeing Public, Ralph Ueltzhoeffer: Project 13 ( Memento of the original from January 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Color Festival at the Bauhaus Dessau

- ^ Art Association Braunschweig: Exhibition of the designs for the light course 2010

- ↑ Braunschweig Parcours 2004 ( Memento of the original from February 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Luminale in Frankfurt

- ↑ Light art at the graduation tower . 3rd Bad Rothenfelde Projection Biennale

- ↑ Forum for Light Art and Architecture ( Memento of the original from January 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ruhrlights 2007 in Mülheim

- ↑ Ruhrlights 2010 ( Memento from May 11, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "GLOW" - Web archive ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ "Narracje" - web archive ( memento of the original from March 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ RUHR.2010 opening, documentation by Joeressen and Kessner

- ↑ Documentation by Geert Mul, Hagen 2010 ( Memento of the original from July 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ "Farbfest am Bauhaus" - web archive ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Professional Lighting Designers Association / PLDA

- ↑ Hildesheim University of Applied Sciences, lighting design

- ↑ Network homepage LUCI ( Memento of 4 May 2011 at the Internet Archive )