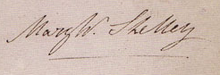

Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley (born August 30, 1797 in London , England , † February 1, 1851 ibid), née Mary Godwin , often referred to as Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley , was a British writer of the early 19th century. She went down in literary history as the author of Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus (1818), one of the most famous works of romantic and fantastic literature . Her oeuvre includes several novels , short stories , plays , essays , poems , reviews , biographies and travel stories . She also edited the work of her late husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley . Her father was the social philosopher and founder of political anarchism William Godwin . Her mother was the writer and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft , who wrote Defense of Women's Rights (1792), one of the fundamental works of the women's rights movement.

Mary Godwin's mother died eleven days after giving birth to her daughter. William Godwin raised his daughter together with her older half-sister Fanny Imlay himself. They received an informal but thoroughly comprehensive upbringing through him and his second wife, Mary Jane Clairmont, during which William Godwin encouraged his daughters to follow his liberal political theories. In 1814, Mary Godwin fell in love with the married Percy Bysshe Shelley, an admirer of her mother's works and a supporter of her father's political ideas. Mary Godwin, who was only 16 years old, followed Percy B. Shelley on a trip through Europe with her stepsister Claire Clairmont . When she returned, Mary Godwin was pregnant. For the next two years, the unmarried couple faced social ostracism for their openly unconventional way of life.

The couple spent the summer of 1816 with Lord Byron , John William Polidori and Claire Clairmont on Lake Geneva . In one of the most frequently described episodes in literary history, Mary Godwin came up with her idea for her novel Frankenstein . Towards the end of 1816, a few weeks after Percy Shelley's first wife, Harriet, committed suicide, the couple married. In 1818 the two settled in Italy for a long time. In 1822 Percy B. Shelley drowned while sailing in the Gulf of La Spezia . A year later Mary Shelley returned to England with her last born and only surviving child, where she successfully continued her writing career. The last decade of her life was marked by disease. She probably died of a brain tumor at the age of 53 .

Until the 1970s, Mary Shelley was mainly perceived as the administrator of her husband's estate and as the author of the novel Frankenstein . Her best-known work is still read two hundred years after its first publication and has been adapted several times for the stage and film. Since the 1970s, literary studies have come to a more comprehensive assessment of their varied work and today also pays tribute to their later novels, such as the historical novel Valperga (1823), Perkin Warbeck (1830), the apocalyptic novel The Last Man (1826) and their last two Tales from Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837). A closer examination of her lesser-known works such as the travelogue Rambles in Germany and Italy (1844) and the biographical essays for Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1829–1846) shows that Mary Shelley represented radical political ideas until the end of her life. In her work there is often the view that social reform can be initiated by cooperative and understanding behavior on the part of women. With this belief she stood in opposition to the individualistic romanticism advocated by Percy Shelley and the political theories of her father, William Godwin.

Life

childhood

Mary Shelley was born Mary Godwin in Somers Town, London in 1797. She was the second child of suffragette and writer Mary Wollstonecraft and the first of the social philosopher William Godwin. Ten days after giving birth, Mary Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever . With the help of housekeepers, William Godwin raised his daughter Mary Godwin and her older half-sister Fanny Imlay , the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft from an illegitimate relationship with the American speculator Gilbert Imlay . A year after Mary Wollstonecraft's death, William Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798), which he understood as a tribute to his deceased wife. In his endeavor to portray her as a free, independent and unconventional woman, he frankly mentioned numerous details from her life in the book. Not only was it described her obsessive passion for the married painter Johann Heinrich Füssli , but also that Fanny Imlay was an illegitimate child, that Mary Wollstonecraft tried twice to commit suicide, that she was pregnant with Mary Godwin before she married William Godwin married and that she refused all religious assistance while she was still on her deathbed. The publication of these memoirs caused a sensation when they first appeared and damaged the reputation of Mary Wollstonecraft for generations. The works of Mary Wollstonecraft and these eye-catching memoirs were available to the children who grew up in the Godwin household . Both girls adored their mother; Mary Godwin later referred to her unconventional life when she entered into a liaison with Percy B. Shelley against her father's wishes.

Judging from the letters of William Godwin and housekeeper Louisa Jones, Mary Godwin's early childhood was happy. However, William Godwin was often heavily in debt and was under the impression that he should not raise the girls alone. On December 21, 1801, he married Mary Jane Clairmont, who lived in the neighborhood and was pregnant by him. She had given her neighbors the impression that she was a widow. However, the two children she brought into the marriage were born out of wedlock and came from two different fathers. William Godwin was known to at least the former at the time of the marriage. Fanny Imlay and Mary Godwin's new step-siblings were three-year-old Claire and six-year-old Charles Clairmont. While William Godwin was very fond of his second wife until the end of his life, Mary Godwin rejected her stepmother with increasing vehemence in the years to come.

Together with his wife, William Godwin founded a publishing bookstore in 1805, for which he also wrote children's books himself. In 1807 the family moved to the vicinity of Clerkenwell, the district where the London booksellers were traditionally based. The Godwin family had their new apartment above the shop, where they sold their books, writing paper, cards and games. Mostly it was Mrs. Godwin and later Fanny Imlay and Mary Godwin who worked in the shop. William Godwin's small company was initially profitable, but was not commercially successful in the medium term. William Godwin borrowed far more money from wealthy acquaintances like publisher Joseph Johnson and admirers like Francis Place than the family could repay.

As was common with middle-class girls at the time, Mary Godwin received little formal schooling. William Godwin believed he did not raise girls on the principles Mary Wollstonecraft had advocated in her defense of women's rights . However, he taught the children on a wide range of subjects. All had access to his extensive library and deal with the numerous intellectuals, poets, journalists, philosophers, politicians and writers who visited William Godwin. Compared to her contemporaries, Mary Godwin received an unusually comprehensive education. Miranda Seymour argues in her biography of Mary Shelley that "... everything we know about his daughters' early years suggests that they were raised in a way their mother would have consented to." The girls had a governess, a tutor , a French-speaking stepmother and (step-) father who wrote children's books and usually read the first drafts to his own children first. The children were expected to write poetry or write stories. Claire Clairmont complained years later about this intellectually demanding environment: “If you cannot write an epic poem or a novel in our family whose originality overshadows all other novels, you are a despicable creature who is not worth it To be recognized. ”In 1811 Mary Godwin attended a girls' boarding school in Ramsgate for a brief period . The fifteen-year-old was described by her father as unusually bold, a little domineering, and alert.

From June 1812, Mary Godwin lived for a few months near Dundee with William Baxter's family, who were among the so-called Dissenters . The reason for the trip is uncertain. Mary Godwin's poor health may have contributed to this as well as William Godwin’s wish that his daughter should experience a family that had committed herself to a radically different life. Mary Godwin felt very comfortable with the Baxter family, which included four daughters. She returned to Scotland again in the summer of 1813 to spend another 10 months there. In the foreword to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein , Mary Godwin described the time there as being formative for her. Her imagination was only able to develop in the wide open landscape.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

From 1814, Mary Godwin had a love affair with Percy Bysshe Shelley. Percy Shelley was an admirer of William Godwin's major work, An Inquiry Concerning Political Justice . However, he had only dealt with the first version from 1793, in which William Godwin celebrated the French Revolution , refused marriage and campaigned for free love on the basis of equal rights. In later editions, William Godwin had clearly moderated his views. The only thing that remained unchanged was his view that great thinkers and artists were entitled to support from wealthy patrons.

Percy Shelley wrote to William Godwin for the first time on January 3, 1812. The latter, who was used to letters of admiration from young, enthusiastic men, initially replied cautiously. Only when he realized that he might find a wealthy patron in the baronet heir Shelley did the correspondence intensify. Percy Shelley eventually promised William Godwin a lifelong grant despite Shelley's own financial situation. His father, the respected Justice of the Peace Sir Timothy Shelley, treated his son more understandingly than Shelley described it in the letters to William Godwin. However, he paid him little or no maintenance. Instead, Percy Shelley raised money by issuing promissory notes on his future inheritance.

Miranda Seymour points out in her biography of Mary Shelley how eccentric, erratic, and unpredictable Percy Shelley's behavior was between 1811 and 1815. She even indicates doubts about his sanity and justifies this with an abundance of examples. Percy Shelley had spontaneously married sixteen-year-old Harriet Westbrook in 1811. This was a boarding school friend of his younger sisters, whom he hardly knew at the time of the marriage. The then 19-year-old saw marriage as the only way to free the young girl from the tyranny of her school and her father. However, his attempt to adopt two young girls whom he wanted to raise personally failed.

In Ireland , where the young couple settled temporarily, Shelley caught the attention of government agencies for distributing pamphlets on human rights and throwing calls for revolution in a bottle into the sea. In his writings, he urged the Irish to found subversive secret societies like that of the Illuminati . Elizabeth Hitchener, a school teacher who gave up her secure existence to live with the couple, was initially worshiped by Percy Shelley as the new Republican " Portia ". A few months later, the couple separated from the teacher because Percy Shelley thought she recognized a "brown demon" after a sudden change of opinion. Just as abruptly he turned away from his young wife Harriet and at times turned to the married Cornelia Turner, who corresponded more to his image of an ideal companion: “I had the feeling as if one had connected a dead and a living body in a disgusting community. One could no longer indulge in self-deception ... "he later described the state of his marriage at the beginning of 1814 to his friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg.

It is possible that Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley met as early as 1813. There is clear evidence of an encounter on May 5, 1814. Shelley's friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg has recorded in his notes how fascinated Percy Shelley was that Mary Godwin was the daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. He had previously shown great interest in Fanny Imlay, Mary Wollstonecraft's oldest daughter. However, her attentive stepmother sent Fanny Imlay on a longer vacation to Wales, thus removing her from the influence of Percy Shelley. Instead, a love affair developed between 16-year-old Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley. On June 26, the two declared their love for each other at Mary Wollstonecraft's grave. Percy Shelley, who is still married to Harriet Westbrook, soon informed William Godwin about the love affair, because he felt that the author of An Inquiry Concerning Political Justice would understand it. Of the £ 2,500 that Percy Shelley had borrowed against a promise to repay £ 8,000 and pledged in full to the heavily indebted William Godwin, he was only to receive £ 1,200. The rest of the money was to be used to finance a joint European trip by Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley. William Godwin felt doubly betrayed: he not only believed he was entitled to the full amount, but also saw his hospitality abused by a person who reinterpreted his long-revised political theories to justify hedonistic actions.

The from debtor's prison threatened William Godwin negotiated with Percy Shelley indeed continue to get the guaranteed sum of money in full. However, he was convinced that he had prevented further meetings between Shelley and Mary Godwin. Mary Godwin, who later described her devotion to her father as "romantic and excessive," found her father's behavior inconsistent. She saw in Percy Shelley the embodiment of the liberal ideas her parents had advocated in the 1790s. Unbeknownst to him, she was still in correspondence with Percy Shelley. Claire Clairmont, later a bookseller, served as the informant. On July 28, the couple secretly left for France with Claire Clairmont.

First trip to Switzerland and return to England

The trio first traveled to Paris . Percy Shelley had expected a money order from his publisher Thomas Hookham to be waiting for him there . However, he had only written him a letter in which he reprimanded him for his irresponsible behavior. So that the 60 pounds that the trio still had to reach their destination Switzerland , they traveled on on foot. A donkey and later a mule carried their luggage. “It was like being in a novel, like a lived romance,” Mary Shelley recalled in 1826 of her journey through war-torn France . On the way they read Mary Wollstonecraft's writings to each other and kept a diary together. In Lucerne , lack of money finally forced her to break off her trip. On September 13, 1814, they returned to England.

The situation that awaited Mary Godwin in England was more complicated than she could have anticipated. She was pregnant, the couple had no financial means, and to Mary Godwin's surprise, her father declined to meet her. It was rumored in London that William Godwin had sold his daughters to Percy Shelley for a few hundred pounds. This is one possible reason why William Godwin stubbornly kept their distance from the couple until Percy Shelley and Mary Godwin got married.

Together with Claire Clairmont, the couple settled in a rented apartment in London. Percy Shelley had to stay away for weeks until November 9 because he was facing arrest by the bailiff for unpaid bills . Only then did he find enough money to satisfy his creditors. Until then, Mary Shelley only met her lover occasionally in hotels, churches, or coffee houses. Two decades later she processed these secret meetings in the novel Lodore . Mary Shelley suffered severe pregnancy problems and a complicated relationship with Percy B. Shelley. In her diary of December 6, 1814, she wrote:

“Very uncomfortable. Shelley and Clary [Claire Clairmont] go out as usual, going to all sorts of places. (…) Harriet [Shelley's wife] [has] been given birth to a son and heir (…). Shelley writes a series of letters about this event, which should be announced with the ringing of bells, because it is about his wife's son. "

Thomas Jefferson Hogg, whom she had little esteem at the beginning of their acquaintance, became increasingly a close friend to her. Percy Shelley, still committed to the ideal of free love, would probably have liked to see the two more closely related. Mary Godwin did not reject this outright because she, in principle, also believed in free love. Her relationship with Hogg doesn't seem to have gone beyond flirting. Emily Sunstein, one of the biographers of Mary Godwin and Percy B. Shelley, is one of the few who think it possible that a brief love affair broke out between the two in 1815. On February 22, 1815, Mary Godwin gave birth to a daughter who was two months premature. She died a few days later. The death of her daughter triggered a depressive phase in Mary Godwin, in which she repeatedly dreamed of little Clara coming back to life. She only got better in the summer and a little later she was pregnant again. The couple's financial situation improved after Percy Shelley received an annuity of £ 1,000 annually from the inheritance of his grandfather, who died on January 5, 1815, as well as an amount to pay off his debts. The couple initially vacationed in Torquay and later rented a small cottage on the outskirts of London. Mary Godwin gave birth to a son on January 24, 1816. He was named after his grandfather William and his parents affectionately called "Willmouse".

Lake Geneva and Frankenstein

In May 1816, Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley traveled again to Switzerland with their young son and Claire Clairmont to spend the summer on Lake Geneva . The destination had been suggested by Claire Clairmont, who hoped to meet Lord Byron there again. The two had had a brief love affair in London and Claire Clairmont was pregnant by the infamous poet. Lord Byron, accompanied by his personal physician John Polidori , was surprised to see Claire Clairmont on Lake Geneva, but quickly made friends with Percy Shelley. He had rented the small "Maison Chapuis" (occasionally also written "Chappuis") in Cologny . A few days later Lord Byron moved into the large and elegant Villa Diodati in the neighborhood. While a Swiss nanny took care of little William, the five adults spent a large part of their time reading, writing and going on boat trips together. Their mutual visits did not go unnoticed by the English public. Lake Geneva was a popular travel destination for wealthy English people and the five people were even observed with telescopes by curious summer guests. The summer stay of the five was a welcome occasion for the English press to speak up again about the blasphemous William Godwin and his daughters living immorally.

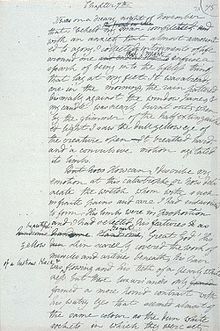

Mary Shelley recalled in a preface to Frankenstein , written fifteen years later , that the summer on Lake Geneva was wet, stormy, and stormy. The never-ending rain forced the group to stay indoors for days. To pass the time, the five talked about the natural philosopher and poet Erasmus Darwin , who allegedly had animated dead matter through experiments, about galvanism and about the possibility of creating artificial life. At night they read horror stories to each other in front of the fireplace in Byron's villa. Byron eventually suggested that everyone should contribute their own horror story for entertainment. In her preface from 1831, Mary Godwin asserted that, unlike the rest of the time, nothing occurred to her for days until she finally had a waking dream:

“(...) I saw the pale student of the unholy arts kneeling next to the thing he had put together. I saw the malicious phantom of a prostrate man and then how signs of life showed up through the work of a mighty machine and he stirred himself with ponderous, semi-living movements (...). Its success would frighten the artist; he would flee in horror from the hideous work. He would hope that the faint spark of life that he had transmitted would fade if he left it to itself (...) and he could sleep in the belief that the silence of the grave was the fleeting existence of this vicious corpse, which he was the source looked at life would choke forever. He's sleeping; but he is awakened; he opens his eyes; sees the hideous thing standing on the side of his bed, opening the curtains and staring at him with yellow, watery, but searching eyes. "

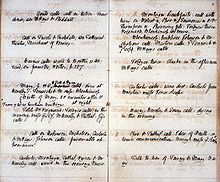

Mary Godwin's biographer Miranda Seymour expresses skepticism about this version of the genesis. Mary Godwin wrote this at a time when she could be sure that no one would contradict her, but at the same time she knew that a good story would help sell the book. John Polidori's detailed diary, on the other hand, reports that everyone except him immediately began working on a story. According to Miranda Seymour, it is possible that Mary Godwin borrowed her version of the genesis from Samuel Coleridge , who had similarly described the genesis of his ballad Christabel in 1816 . Mary Godwin's diary from this period has been lost; what has been preserved begins on July 22, 1816, and Mary Godwin uses the short notes write and write my story to record that she was working on a story.

On August 29, Percy Shelley, Mary Godwin and Claire Clairmont left for London with little William and his Swiss nanny. Percy Shelley had previously made arrangements with Lord Byron about what to do with the child Claire Clairmont was expecting from him. With them they had numerous manuscripts that had been written during the summer.

Marries Percy B. Shelley

After returning to England, Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley settled in Bath . Claire Clairmont moved into an apartment near her. The choice fell on the remote Bath, because the three hoped to be able to keep Clairmont's pregnancy a secret. The pregnancy was even hidden from Fanny Imlay, who in desperate letters to Mary Godwin complained about her life with her stepfamily. Percy Shelley and Mary Godwin refrained from taking in Fanny Imlay, presumably because of Claire Clairmont's pregnancy. On October 9th, Fanny Imlay committed suicide. It wasn't the only suicide that Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley had committed. On September 10, the body of Percy Shelley's wife Harriet had been found, who drowned herself in Serpentine Lake in London's Hyde Park . Both suicides were covered up. For fear of a scandal, it was also accepted that Fanny Imlay was anonymously buried in a poor grave .

Percy Shelley's attempt to obtain custody of their children after the death of his wife met resistance from Harriet Shelley's family. His lawyer made it clear that ending his unorthodox lifestyle would improve his chances of success in court. On December 30, 1816, again pregnant Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley married in St Mildred's Church in London. William Godwin and his wife were present. Despite the marriage, the court found in March 1817 that Percy Shelley was morally unfit to raise his children. They were entrusted to a pastor's family. On September 2, Mary Godwin gave birth to her third child, whom she named after her first daughter, Clara, who died young. In November 1817 the travel story History of a Six Weeks' Tour appeared , which Mary Godwin had written on the basis of the revised letters and diary entries of her two trips to Switzerland. Frankenstein's publication followed on January 1, 1818 . The book appeared without an author's name, but with a foreword by Percy Shelley and was dedicated to William Godwin. Critics and readers alike concluded that Percy Shelley was the author. Although Sir Walter Scott praised the novel in his review, it was initially not a sales success.

Mary and Percy B. Shelley left England again on March 12, 1818. In addition to the Swiss nanny, the children William and Clara, Claire Clairmont and her daughter Allegra , born on January 13, traveled with them . None of them intended to ever return to England.

Italy

Lord Byron had agreed to raise Allegra. Percy and Mary Shelley therefore first traveled to Venice to hand them over to their father. The Shelley family felt at home in Italy, but did not stay in any place for long periods of time. They lived for a short time in Livorno , Florence , Este , Naples , Rome , Pisa , Bagni di Pisa and San Terenzo. Everywhere they managed to gather a circle of friends, some of whom accompanied them for a while. Mary Shelley's stay in Italy was overshadowed by the death of her two children. Clara died in Venice in September 1818, William, just under three and a half years old, in Rome in June 1819. The death of her children plunged her into a severe depression, which she isolated from Percy Shelley. He wrote in his diary:

- My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone,

- And left me in this dreary world alone?

- Thy form is here indeed — a lovely one—

- But thou art fled, gone down a dreary road

- That leads to Sorrow's most obscure abode.

- For thine own sake I cannot follow thee

- Do you return for mine.

For a time Mary Shelley found solace only in writing. It was not until the birth of her fourth child, Percy Florence, on November 12, 1819, that she helped to break out of her depression. Despite the great personal losses Mary Shelley suffered in Italy, it became for her a country that "painted memory as paradise". For both Mary Shelley and her husband, the years they spent in Italy were a time of intense intellectual debate and creativity. While Percy Shelley wrote a number of his most important poems during this time, Mary Shelley wrote the novella Matilda , the historical novel Valperga and the plays Proserpine and Midas . The royalties for Valperga were meant to help her father financially, as Percy Shelley has since refused to help him financially. However, Mary Godwin also had to learn to deal with Percy Shelley's interest in other women. Since Mary Shelley shared her husband's belief that marriage is not an exclusive, lifelong contract, she accepted that and developed close friendships with men and women around her. Her friends included the Greek freedom fighter Prince Alexander Mavrocordatos and Jane and Edward Ellerker Williams .

In December 1818, the Shelleys traveled with Claire Clairmont and her servants to Naples, where they stayed for three months. They found there that two former servants, Paolo and Elise Foggi, friends of the Shelleys had informed that Percy Shelley had registered a two-month-old girl with an Italian authority as the child of Mary Shelley on February 27, 1819. The Foggi couple claimed that it was a child of Claire Clairmont. The ancestry of the girl is still one of the unexplained points in the life of the Shelleys. It is possible that Percy Shelley adopted an Italian girl in his typical spontaneity to comfort Mary Shelley for the loss of little Clara. It is also possible that it was a daughter of Percy Shelley. The mother could have been a chance acquaintance of Percy Shelley, but Elise Foggi or Claire Clairmont could also be the mother. However, Mary Shelley always emphasized that she would have known if Claire Clairmont had been pregnant. It is also possible that Percy Shelley wanted to give an illegitimate child of Lord Byron an origin. Little Elena Adelaide Shelley, who was taken care of by unknown people in Naples while the Shelleys lived in Rome, died on June 9, 1820.

In the summer of 1822, Mary Shelley, who was again pregnant, moved into a villa on the coast near San Terenzo with her husband, Claire Clairmont and Edward and Jane Williams . Shortly after moving in, Percy Shelley had to inform Claire Clairmont that her daughter Allegra had died of typhus . On June 16, Mary Shelley miscarried and lost so much blood that her life was in danger. Presumably, Percy Shelley saved his wife's life by putting her in an ice bath to stop the bleeding. However, the relationship between the two spouses was no longer as harmonious as before. Percy Shelley spent more time with Jane Williams than with his dejected and ailing wife. Most of the short poems Percy Shelley wrote in San Terenzo were addressed to Jane Williams.

Percy Shelley and Edward Williams bought a sailboat together with which they sailed down the coast to Livorno with Captain Daniel Roberts. Percy Shelley met Lord Byron and the publisher Leigh Hunt there to discuss the publication of a new, political, liberal magazine. On July 8, he sailed back to San Terenzo as boat boys with Edward Williams and 18-year-old Charles Vivian. They never got there. Instead, Mary Shelley received a letter from Leigh Hunt in which he asked Percy Shelley for information about the return journey. Mary Shelley immediately set off for Livorno and then Pisa with Jane Williams, hoping to find their husbands still alive. Ten days later, the bodies of the three sailors washed up on the coast of Viareggio . Edward Trelawney, Leigh Hunt and Lord Byron cremated Shelley's body while it was still on the bank.

Widow life

Mary Shelley lived in Genoa with Leigh Hunt and his family for the first year after the death of her husband . She had chosen to make a living from her writing. However, her financial situation was precarious. On July 23, 1823 she returned to England and initially lived with her father and stepmother until a small payment from her father-in-law enabled her to rent her own apartment. Sir Timothy Shelley had offered to pay for the upbringing of his grandson Percy Florence Shelley. However, he made this subject to the condition that his grandson should live with a guardian. Mary Shelley declined this offer. Finally Sir Timothy Shelley granted her a small annual pension. This was linked to the condition that Mary Shelley did not publish a biography of her husband and did not publish any further volumes of poetry with his work. Timothy Shelley wanted to ensure that people forgot which radical ideas his son had advocated. The volume of poetry Posthumous Poems of PB Shelley , which Mary Shelley had published in 1824, Timothy largely bought up and had the books destroyed. He refused to meet his daughter-in-law in person until the end of his life. He was represented by lawyers in all negotiations with her. In 1825 Charles Shelley, the son of Percy Shelley and his first wife Harriet, died. As a result of this death, Mary Shelley's son became the heir to Shelley's property. Sir Timothy then increased the annual pension from £ 100 to £ 250.

From 1824 to 1826, Mary Shelley worked primarily on her novel The Last Man (published 1826) and helped several friends who wrote memoirs of Lord Byron and Percy Shelley. This was also the beginning of her attempt to make her husband immortal. She met the American actor John Howard Payne and the American author Washington Irving . Payne fell in love with her and asked for her hand in 1826. Mary Shelley refused on the grounds that after marrying one genius, she could only marry another one. Payne accepted this refusal and tried unsuccessfully to persuade his friend Washington Irving to hold her hand. Mary Shelley knew about it, but it is not clear whether she took it seriously.

In 1827 Mary Shelley was involved in enabling her friend Isabel Robinson and her lover Mary Diana Dods , who wrote under the name David Lyndsay, to lead a life as man and woman in France. With the help of John Howard Payne, who was not privy to the details, Mary Shelley managed to obtain false passports for the couple. In 1828 she contracted smallpox when she visited the couple in Paris. It took weeks for her to recover from the disease. She survived it without scars, but was visibly aged afterwards.

From 1827 to 1840, Mary Shelley was very active as a writer and editor. She wrote the novels Perkin Warbeck (published 1840), Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837). She wrote five volumes for Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men , an encyclopedia edited by Dionysius Lardner . She also wrote short stories for women's magazines. She supported her father financially and they both helped each other to find publishers. In 1830 she sold the copyright to a new Frankenstein edition to publishers Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley for £ 60 . Her father died in 1836 at the age of eighty. As he had requested in his will, Mary Shelley began editing his letters for an edition. After two years, however, she gave up the project. Since the death of her husband, she had promoted his work and regularly quoted his poems in her own work. In the summer of 1838, Edward Moxon , editor of Alfred Tennyson and son-in-law of Charles Lamb , offered her to publish the collected works of Percy Shelley. Mary Shelley received £ 500 for her work as editor. Timothy Shelley gave his approval but continued to insist that no biography of Percy Shelley should be published. Mary Shelley found a way to introduce readers to the story of Percy Shelley's life. She added detailed explanations to the poems that contained numerous biographical information.

Mary Shelley doesn't seem to have wanted a new relationship with a man even after the episode with Johne Howard Payne. In 1828 she met the French writer Prosper Mérimée and probably flirted with him. The only received letter to him is usually interpreted as a gentle rejection of his declaration of love. She was happy when her old friend Edward Trelawny returned to England from Italy and both joked in their letters about a possible marriage. Their friendship cooled after Mary Shelley refused to work with him on a biography of Percy Shelley. Trelawny also reacted very upset that Mary Shelley deleted the atheistic lines from Percy Shelley's poem Queen Mab . Some observations in the diaries from the early 1830s to 1840s suggest that Mary Shelley felt very deeply for the radical politician Aubrey Beauclerk . The feelings seem to have been one-sided, however, as he married twice during these years, including Rosa Robinson, a friend of Mary Shelley.

At the center of Mary Shelley's life was her son Percy Florence. According to his father's wishes, he attended a private school. To save on boarding costs, Mary Shelley moved to Harrow on the Hill so that Percy Florence could attend the local private school as a day pupil. He then studied law and politics at Trinity College , Cambridge . But he did not have the talent of his parents. Mother and son were on good terms, and after Percy Florence retired from university in 1841, he returned to live with Mary Shelley.

Last years of life

In 1840 and 1842 to 1843, mother and son made two trips to the European continent together. In Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843 (published 1844) Mary Shelley tells of these trips. Timothy Shelley died in 1844 at the age of ninety. The income from the family property was less than the Shelleys had hoped. Nevertheless, mother and son were financially independent for the first time. In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley was the victim of several blackmail attempts. In 1845 the Italian exile Gatteschi, whom Mary Shelley had met in Paris, threatened to publish the letters she had sent him. A friend of her son bribed a police chief, who then confiscated all of Gatteschi's papers and destroyed the letters underneath. A short time later, Mary Shelley bought up some letters written by her and Percy Bysshe Shelley. The seller was a man who called himself G. Byron, who posed as the illegitimate son of the late Lord Byron. In 1845, Percy Shelley's cousin Thomas Medwin threatened to publish a damaging biography of Percy Shelley. For a payment of £ 250 he wanted to forego publication. Mary Shelley declined payment. According to the literary scholar Bieri, Medwin had claimed that he knew details of what happened in Naples. To this day, Thomas Medwin is the main source that the child registered in Naples is an illegitimate daughter of Shelley with an unknown woman.

In 1848 Percy Florence and Jane Gibson married St John. The marriage turned out to be a happy union. Mary Shelley developed a very close relationship with her daughter-in-law and lived with her on the Shelley's estate in Field Place, Sussex . Mary Shelley's last years were marked by illness. From 1839 she suffered from headaches and partial paralysis, so that she could often neither read nor write. She died in London on February 1, 1851, at the age of 53. Her doctor suspected that she died from a brain tumor. According to her daughter-in-law Jane Shelley, Mary Shelley had wished to be buried at the side of her mother and father. Percy Florence and Jane Shelley found the graveyard of St Pancras Church too depressing. They therefore had her buried in the graveyard of St Peter's Church in Bournemouth . On the first anniversary of her death, the Shelleys opened their desk drawer. There they found curls of their deceased children, a notebook that she had shared with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a copy of his poem Adonaïs . One page of the poem was folded around a small, silk parcel containing some of Percy Shelley's ashes and the remains of his heart.

Literary work

Mary Shelley led a literary life. Her father encouraged her to learn to write by writing letters, and as a child her favorite activity was writing stories. Unfortunately, all of Mary Shelley's early work was lost during her first visit to the European continent. None of the remaining manuscripts can be dated before 1814. Mounseer Nongtongpaw , which appeared in William Godwin's Juvenile Library when Mary Shelley was ten, is often cited as her first published work . In the most recently published complete works, however, this poem is mostly attributed to a different author.

Novels and short stories

Mary Shelley's literary work includes six novels and one short story. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is her first novel, which she wrote when she was only twenty and on which her fame, which continues to this day, is largely based. In 1819 she wrote the novella Matilda , but it was not published for the first time until 1959. Matilda is about a father's incestuous desire for his daughter, his suicide after he admitted this desire and the daughter's melancholy longing for death after the death of her father. Incest topics were frequently taken up by romantic writers and can also be found in the work of Lord Byron, Horace Walpoles , Matthew Lewis and even William Godwin. Godwin, however, strongly advised his daughter against the publication of this novella and Mary Shelley apparently quickly followed his view. Publication of this story would probably have resulted in Mary Shelley's and Claire Clairmont's sensational relationship with Percy B. Shelley and Lord Byron again being widely discussed in public. After Percy B. Shelley's death, Mary Shelley was dependent on not further straining the strained relationship with Sir Timothy Shelley, so that this point in time also seemed unsuitable for publication.

Valperga: Or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca (1823), like The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830), is a historical novel. Valperga is set in 14th century Italy and connects the life story of the historical person Castruccio Castracani with the fictional life story of two women. Mary Shelley dealt intensively with Italian history during the time she was working on Valperga . In her novel, Mary Shelley makes frequent references to the political and social situation in Italy at the beginning of the 19th century.

Mary Shelley worked on the novel The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck from 1827 to the autumn of 1829. In it she takes up the story of Perkin Warbeck , who during the reign of Henry VII passed himself off as Richard, Duke of York , one of the two princes who were under the reign of Richard III. were interned in the Tower of London and, according to the prevailing opinion, died there. Mary Shelley assumes in her novel that Perkin Warbeck was the rightful heir to the throne. Similar to Valperga , Mary Shelley did extensive research while she was working on the novel. Correspondence partners she asked for advice on individual historical issues included Thomas Crofton Cocker , Walter Scott , John Bowring, and John Murray .

Between these two novels, Mary Shelley wrote The Last Man (1826), a novel that is more difficult to classify into a genre. It is set at the end of the 21st century, in a phase in which English politics is going through a phase of transition. At the end of this transition phase, England will either be a Roman republic, a democracy or a monarchy. In this novel, Mary Shelley addresses a range of political, philosophical and social aspects that, in the opinion of many literary scholars, can only be compared with her first work, Frankenstein .

In the novel Lodore (1835), Mary Shelley primarily addresses issues of upbringing. In doing so, she takes up a topic that both of her parents have dealt with in great detail. Similar to her mother, Mary Shelley rejected an upbringing whose orientation and depth is determined by the gender of the child, and this is illustrated in this story. The novel can thus be counted among the so-called " silver fork novels ", which derive their storylines from the social conventions of aristocratic circles and were very popular in England in the 1820 and 1830s. Benjamin Disraeli and Edward Bulwer are among the best-known authors of this direction . The latter in particular had a major influence on the work of Mary Shelley during the 1830s.

Lodore was selling well and her editor suggested Mary Shelley make her next novel similar. In fact, the novel Falkner, published in 1837, bears many similarities to Lodore , but more than this deals with the relationship between a father and a daughter who are largely isolated from society. Mary Shelley considered this novel to be one of her best and has repeatedly noted how easy it was for her to write Falkner . In today's literary studies, however, relatively little attention has been paid to this novel.

Autobiographical elements in the narratives

There is no consensus in literary studies on the extent to which Mary Shelley's stories are autobiographical. Critics have pointed out the repeated examination of father-daughter relationships in their work. The two novels Falkner and Lodore deal with this topic, and it is the central theme of the novella Matilda . Today, Matilda is mostly interpreted as a narrative in which Mary Shelley processed the feeling of loss after the death of her two children and her emotional alienation from William Godwin.

Mary Shelley herself has pointed out that the characters in her novel The Last Man reflect the characters of her so-called "Italian circle". Lord Raymond, who leaves England to fight alongside the Greek freedom fighters and dies in Constantinople , is based on Lord Byron. Adrian, Earl of Windsor, who searches for paradise on earth with his followers and dies when his boat goes down in a storm, is the fictional portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley. However, in her review of William Godwin's novel Cloudesley (1830), Mary Shelley also stated that it is not enough for a writer to limit himself to portraying people around him. William Godwin, too, viewed the characters his daughter created more as stereotypes than as a faithful description of real people. A number of literary scholars such as Patricia Clemit and Jane Blumberg have subscribed to this view and reject a far-reaching autobiographical interpretation of Mary Shelley's work.

Genres and the ideas of the Enlightenment and Romance

Mary Shelley has used different genres in the course of her work to express her views. These include a form of novel that was strongly influenced by her father in the 1790s with his novel Caleb Williams , which thematizes the mutual relationship between a person and the society in which he lives. This type of novel is referred to in English as the "Godwinian Novel". Her first novel Frankenstein , which is also counted among the so-called horror novels , is strongly influenced by this type of novel and takes up topics that her father also placed at the center of his novels. While the novel is primarily concerned with the fate of the protagonist Victor Frankenstein, Mary Shelley uses the text to justify her idea of political romanticism . In this she criticizes the individualism and egocentrism of the traditional romantic movement. Victor Frankenstein recalls the figure of Satan in Paradise Lost and Prometheus : he rebels against tradition, creates life and shapes his own destiny. This is by no means portrayed positively. His pursuit, which Victor Frankenstein misunderstands as a search for truth, forces him to leave his family and ends in disaster. Unlike William Godwin, Mary Shelley is critical of the ideals of the Enlightenment . The early “Godwinian Novels” show how the rational action of an individual gradually contributes to the improvement of society itself. Mary Shelley, on the other hand, addresses in both The Last Man and Frankenstein how little an individual has an influence on the course of history.

While Mary Shelley believed in the Enlightenment concept that man would improve society through responsible use of power, she also feared that irresponsible exercise of power would lead to chaos. In doing so, she ultimately criticizes the convictions of her parents, who, like many intellectuals of the 18th century, were convinced that a positive change in society was inevitable. The artificial creature that Victor Frankenstein creates may read books that represent political ideas like those of her parents, but this education is ultimately useless to him. Mary Shelley's work is thus less optimistic than that of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. She lacks belief in William Godwin's theory that society will inevitably perfect itself. According to literary scholar Kari Lokke, Mary Shelley goes even further in The Last Man and even questions our right to put humans at the center of the universe.

In her historical novels, Mary Shelley is heavily influenced by Walter Scott. However, she mostly uses this genre to express herself on the relationship between the sexes. Valperga is a novel that stands in marked contrast to Walter Scott's rather masculine novels. She uses the two historically unproven female figures that Shelley makes the main characters of the plot to question established theological and political institutions. With the main female characters, Mary Shelley opposes the essential character trait of the main male character Castruccio with an alternative: understanding and sensitivity. In Perkin Warbeck , Mary Shelley's other historical novel, Lady Gordon represents friendship , domesticity, and equality . She too personifies an alternative to the male striving for power, which ultimately destroys the male character.

Short stories

In the 1820s and 1830s, Mary Shelley wrote a number of short stories for almanacs and gift books. They were frequently published in The Keepsake , a silk-bound series of almanacs aimed at middle-class women. It was mostly commissioned work in which the author contributed a story to a given illustration. In addition to Mary Shelley, other authors such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge also used this profitable marketing channel. Mary Shelley's short stories mostly address the fragility of individual identity and the different values that society attaches to men and women. Mary Shelley wrote a total of twenty-one such short stories between 1823 and 1839. She herself did not give short stories a high priority and wrote to Leigh Hunt, among others, that she hoped to wash off the mud of the short stories with the clear water of a new novel .

Travel stories

During their first trip to France in 1814, Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley kept a diary together. They published this in a revised form in 1817 under the title History of a Six Weeks' Tour . The travel story also contains two letters each from Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley on their visit to Geneva in 1816, as well as Percy Shelley's poem Mont Blanc . The travel story celebrates youthful love and political idealism, but also deals with the consequences of the political turmoil in France and the work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau . The travel story deliberately follows the example of Mary Wollstonecraft, who thematized her political views and way of life in her travel stories.

Mary Shelley's last great work, which appeared in 1844, is the travel story Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843 , which reports in letter form about her journey with her son Percy Florence and his university friends through Germany and Italy. Between reports on the sights and the people she meets, she also uses the travel narrative to reflect on her role as a widow and mother as well as the national movement in Italy. In it she speaks out clearly against the monarchy, a division of society into classes, slavery and war.

Biographies

Between 1832 and 1839 Mary Shelley wrote several biographies for Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia. This series was one of the numerous series that were produced between the 1820s and 1830s to meet a growing demand, especially from the middle class, for books that were used for further education. By the time these biographies were reissued in 2002, their importance in Mary Shelley's work was overlooked. According to the literary scholar Greg Kucich, they are evidence of Mary Shelley's careful research. Mary Shelley wrote her biographies in the style that Samuel Johnson made popular with his work Lives of the Poets (1779 to 1781) and combines memories, secondary literature and anecdotal traditions with her own evaluation of the respective person. Mary Shelley saw their biographies as an opportunity to substantiate their political views. For example, she often criticized male-dominated customs such as primogeniture . On the other hand, she emphasizes the family background of her subjects - mostly well-known Italians, French and Portuguese - and focuses on emotional issues. In this she resembles the early female historians like Mary Hays and Anna Jameson . The biographies had a circulation of around 4,000 copies per volume and thus exceeded the circulation of their novels.

Work as editor

Mary Shelley was determined to write his biography shortly after the death of her husband. However, this project was stopped by Sir Timothy Shelley for decades. Instead, Mary Shelley endeavored to establish her husband's reputation as an outstanding poet by publishing his poems. Posthumous Poems appeared in 1824 , an edition that was largely bought up by her father-in-law. Her goal of helping her husband to achieve what she saw as the fame she felt she achieved with a new edition of his poems in 1839. The following year Mary Shelley edited a volume of the essays, letters, translations, and fragments of his work, and during the 1830s she ensured that his poems were regularly published in almanacs such as The Keepsake . Avoiding Sir Timothy's request that no biography of Percy Shelley be published, Mary Shelley often annotated these editions with notes about the life and work of her husband. To ensure that he received a proper appreciation for the Victorian era , she portrayed Percy Shelley as a lyric poet rather than a radical political poet. She justified his Republican attitude as an expression of compassion for the needy. With the help of anecdotes, she underlined his basic benevolence, his domesticity and his love for nature. She portrayed herself as a practical muse who often suggested revisions to his work.

Her editions were based on Percy Shelley's messy, sometimes illegible notebooks, which she tried to arrange chronologically, and she also included poems in her editions that were addressed to women other than herself. From the point of view of today's literary scholars, however, she copied some of the works incorrectly, misinterpreted, deliberately changed and thus sometimes depicted Percy Shelley differently than he actually was. Today's editors of Percy Shelley such as Donald Reiman still use their edition and point out that their work fell at a time when it was not yet the primary goal of an editor to give readers an accurate and complete overview in an entire edition to give about a person's work.

One of Mary Shelley's most famous interventions in her husband's work is the removal of the atheistic passages in the first edition of the poem Queen Mab . It is not clear whether this was done on its own initiative or at the instigation of the publisher Edward Moxon. In the second edition, the poem appeared in full, whereupon Edward Moxon was indicted and found guilty of blasphemy . Her notes are still considered to be an essential source for a discussion of Percy Shelley's work. It is also beyond dispute that she was the driving force behind ensuring that Percy Shelley received adequate appreciation for his life. Without her committed advocacy, he would certainly have been forgotten in the decades after his death.

Reception history

Mary Shelley was a well-respected writer throughout her life. However, many of her contemporaries overlooked the political message of her work. After her death, she was quickly recognized primarily as the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley and as a writer by Frankenstein . Julie A. Carson points out in the introduction to her book England's First Family of Writers that the life stories of Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin and Mary Shelley are often more fascinating than their respective works. Mary Shelley's life was dramatic and her biography has influenced both the scholarly evaluation and public acceptance of her work. In the 19th and first seven decades of the 20th century, the focus on her biography and the influence of her person on the work of Percy B. Shelley often obscured the view of her importance as a writer. Graham Allen even speaks of being "depoliticized" and "domesticated". It was ignored that Mary Shelley was commercially more successful than her husband and that she achieved higher editions than the other members of her illustrious literary circle. Her influential novel Frankenstein was seen less as her own achievement, but rather believed to be the inspiring achievement of Percy B. Shelley and Lord Byron. When some of her letters were published in 1945, the editor Frederick Jones wrote that "such an extensive collection is not justified because of its fundamental quality or because of Mary Shelley's importance as a writer, but that it deserves this attention only as the wife of Percy Shelley". This attitude was still widespread in literary studies in the 1980s, and when Betty T. Bennett began publishing all of her letters in the 1980s, she referred to Mary Shelley as a woman who until a few years ago was a "result of literary studies “Was considered: William Godwin's and Mary Wollstonecraft's daughter who became Percy Shelley's Pygmalion . Emily Sunstein's biography Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality , which appeared in 1989, was the first scientifically based biography of the writer.

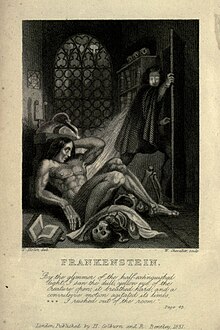

Frankenstein is still Mary Shelley's most famous story. The numerous adaptations for film and stage contributed significantly to this. Frankenstein was first brought to the stage in 1823. The first film adaptation followed in 1910, the second film adaptation from 1931, in which Boris Karloff plays the monster created by Victor Frankenstein, became a classic of horror films . In 1974, Mel Brooks made a parody of the horror films of the 1930s with Frankenstein Junior , and in 1994, Kenneth Branagh's Mary Shelley's Frankenstein made another film version that closely followed the novel. By contrast, literary studies have dealt more intensively with the complete works of Mary Shelley since the 1970s. This is in large part due to feminist literary studies, which gained in importance from the 1970s and led to numerous new approaches. Ellen Moers was one of the first to interpret Mary Shelley's work from a psychoanalytic point of view, arguing that the loss of her first child had a significant impact on the genesis of Frankenstein . She argues that the novel is a "birth myth" with which Mary Shelley processed that she both caused her mother's death and failed as a parent with the death of her child. In their book The Madwoman in the Attic , published in 1979, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar primarily questioned Mary Shelley's relationship to the male literary tradition. According to her interpretation, Mary Shelley accepts this male tradition, including her inherent skepticism towards people, but secretly cherishes " fantasies of equality that occasionally erupt in monstrous images of anger ". From the point of view of the literary scholar Mary Poovey , Mary Shelley's works often testify to the author's literary self-confidence at the beginning. But they lead to conventional female behavior. According to Mary Poovey, the numerous storylines of Frankenstein allow Mary Shelley to simultaneously express her radical desires and negate them.

Most of Mary Shelley's works have been reprinted in the past 30 years. Today she is considered one of the major authors of Romanticism.

Some of Mary Shelley's manuscripts can be found in the Bodleian Library , New York Public Library , Huntington Library , British Library, and the John Murray Collection.

In 2004 she was posthumously inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame .

bibliography

- Novels

- Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus . (1818)

- Matilda. (1819, published 1959)

- Valperga, or the Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca . (1823)

-

The Last Man. (1826)

- German: Verney, the last man . Translated by Ralph Tegtmeier. Bastei Lübbe 1982. Also as: The Last Man. Translated by Maria Weber. BoD 2018.

- The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck . (1830)

- Lodore. (1835)

- Falconer. (1837)

- Novellas and short stories

- Valerius: The Reanimated Roman. (1819)

- A Tale of the Passions; or, The Death of Despina. (1822)

- The Bride of Modern Italy. (1824)

- Ferdinando Eboli. (1828)

- The Sisters of Albano. (1828)

- The Evil Eye. (1830)

- The False Rhyme. (1830)

- The Mourner. (1830)

- The Swiss Peasant. (1830)

-

The transformation. (1830)

- German: The uncanny metamorphosis. In: Alden H. Norton (ed.): A skull made of sugar. Heyne General Series # 867, 1971.

- The dream. (1831)

- The Pole. (1832)

-

The Mortal Immortal. (1833)

- German: The mortal immortal. JMB Verlag , Hannover 2020, ISBN 978-3-95945-021-8 .

- The Elder Son. (1835)

- The Parvenue. (1836)

- The Pilgrims. (1838)

- Euphrasia. (1839)

- Roger Dodsworth: The Reanimated Englishman. (1863, also called The Reanimated Man. )

- The Heir of Mondolfo. (1877)

- The Brother and Sister: An Italian Story. (1891)

- The Recalcitrant Robot. (1966)

- Travel reports

-

History of a Six Weeks' Tour. (1817)

- German: Escape from England. Travel memories and letters 1814–1816. Edited and translated from English by Alexander Pechmann. Achilla Press, Hamburg 2002.

-

Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843. (1844)

- German: Forays through Germany and Italy in the years 1840, 1842 and 1843. Translated by Nadine Erler and with an afterword by Rebekka Rohleder. Volume 1: Corso, Wiesbaden 2017, ISBN 3-7374-0742-8 , Volume 2: Corso, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 3-7374-0745-2 .

literature

- Graham Allen: Mary Shelley. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 0-230-01908-0 .

- Betty T. Bennett: Finding Mary Shelley in her Letters . Romantic revisions. Ed. Robert Brinkley and Keith Hanley. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-38074-X .

- Betty T. Bennett (Ed.): Mary Shelley in her Times. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2003, ISBN 0-8018-7733-4 .

- Betty T. Bennett: Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: An Introduction. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1998, ISBN 0-8018-5976-X .

- Betty T. Bennett, "The Political Philosophy of Mary Shelley's Historical Novels: Valperga and Perkin Warbeck ". The Evidence of the Imagination . Ed. Donald H. Reiman, Michael C. Jaye, and Betty T. Bennett. New York University Press, New York 1978, ISBN 0-8147-7372-9 .

- James Bieri : Percy Bysshe Shelley, a Biography: Exile of Unfulfilled Reknown, 1816-1822. University of Delaware Press, Newark 2005, ISBN 0-87413-893-0 .

- Jane Blumberg: Mary Shelley's Early Novels: "This Child of Imagination and Misery" . University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 1993, ISBN 0-87745-397-7 .

- William C. Brewer: William Godwin, Chivalry, and Mary Shelley's The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck ". Papers on Language and Literature 35.2 (Spring 1999): 187-205. Rpt. On bnet.com. Retrieved on February 20, 2008.

- Charlene E. Bunnell: All the World's a Stage: Dramatic Sensibility in Mary Shelley's Novels. Routledge, New York 2002, ISBN 0-415-93863-5 .

- Pamela Clemit: From "The Fields of Fancy" to "Matilda". Mary Shelley in her Times. Ed. Betty T. Bennett. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2003, ISBN 0-8018-7733-4 .

- Pamela Clemit: The Godwinian Novel: The Rational Fictions of Godwin, Brockden Brown, Mary Shelley. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1993, ISBN 0-19-811220-3 .

- Ernest Giddey: Mary Shelley. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Sandra Gilbert, Susan Gubar: The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. 1979. Yale University Press, New Haven 1984, ISBN 0-300-02596-3 .

- Robert Gittings, Jo Manton. Claire Clairmont and the Shelleys. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1992, ISBN 0-19-818594-4 .

- Richard Holmes: Shelley: The Pursuit. 1974. Harper Perennial, London 2003, ISBN 0-00-720458-2 .

- Anne K. Mellor: Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. Routledge, London 1990, ISBN 0-415-90147-2 .

- Mitzi Myers: Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley: The Female Author between Public and Private Spheres. Mary Shelley in her Times. Ed. Betty T. Bennett. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2003, ISBN 0-8018-7733-4 .

- Clarissa Campbell Orr: Mary Shelley's Rambles in Germany and Italy. the Celebrity Author, and the Undiscovered Country of the Human Heart . Romanticism On the Net 11 (August 1998).

- Alexander Pechmann : Mary Shelley: Life and Work. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 978-3-538-07239-8 .

- Mary Poovey : The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1985, ISBN 0-226-67528-9 .

- Karin Priester : Mary Shelley - The woman who invented Frankenstein. EA Herbig Verlagbuchhandlung, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-7844-2816-9 .

- Fiona Sampson: In search of Mary Shelley: the girl who wrote Frankenstein. Profile Books, London [2018], ISBN 978-1-78125-528-5 .

- Esther Schor (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-00770-4 .

- Miranda Seymour : Mary Shelley. John Murray, London 2000, ISBN 0-7195-5711-9 .

- Melissa Sites: Re / membering Home: Utopian Domesticity in Mary Shelley's Lodore . A Brighter Morn: The Shelley Circle's Utopian Project. Ed. Darby Lewes. Lexington Books, Lanham, MD 2003, ISBN 0-7391-0472-1 .

- Johanna M. Smith: A Critical History of "Frankenstein". Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2000, ISBN 0-312-22762-0 .

- Muriel Spark: Mary Shelley. Cardinal, London 1987, ISBN 978-0-7474-0318-0 .

- German edition: Muriel Spark: Mary Shelley. A biography. Insel Taschenbuch, 1992, ISBN 3-458-32958-7 .

- William St Clair: The Godwins and the Shelleys: The Biography of a Family. Faber & Faber, London 1989, ISBN 0-571-15422-0 .

- Emily W. Sunstein: Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality. 1989. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1991, ISBN 0-8018-4218-2 .

- Janet Todd : Death & the Maidens. Fanny Wollstonecraft and the Shelley Circle. Counterpoint, Berkeley 2007, ISBN 978-1-58243-339-4 .

- Ann M. Frank Wake: Women in the Active Voice: Recovering Female History in Mary Shelley's "Valperga" and "Perkin Warbeck". In: Syndy M. Conger, Frederick S. Frank, Gregory O'Dea (Eds.): Iconoclastic Departures: Mary Shelley after "Frankenstein". Essays in Honor of the Bicentenary of Mary Shelley's Birth. Farleigh Dickinson University Press, Madison, NJ 1997, ISBN 0-8386-3684-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Mary Shelley in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Mary Shelley in the German Digital Library

- Works by Mary Shelley in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Mary Shelley in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Works by Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- Mary Shelley in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Mary Shelley in the Science Fiction Awards + Database (English)

- Works by and about Mary Shelley at Open Library

- The edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein Notebooks. The Shelley-Godwin Archive, accessed June 9, 2016 .

- extensive page on Shelley's novel Frankenstein, films, comics, theater on frankensteinfilms.com (English)

- Bibliography on fantasticfiction.co.uk

- Short biography on weltchronik.de (German)

- Informative page about Shelley on maryshelley.nl, with annotated version of the novel Frankenstein (English)

Individual evidence

The abbreviations “(CC)” and “(OMS)” refer to two collections of essays. "(CC)" refers to the essay collection " The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley " and "(OMS)" refers to the essay collection " The Other Mary Shelley "

- ↑ Pechmann, p. 8.

- ↑ Kenneth Ross Hunter: John Clarke (1760-1815): Licentiate in Midwifery of the Royal College of Physicians of London and Doctor of Medicine of the University of Frankfurt an der Oder. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 18, 1999, pp. 297-303; here: p. 299.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 28-29; St Clair, pp. 176-178.

- ↑ Priest, p. 31

- ↑ Melanie Phillips: The Ascent of Woman - A History of the Suffragette Movement and the ideas behind it. Time Warner Book Group, London 2003, ISBN 0-349-11660-1 , p. 14.

- ^ Julie A. Carson: England's First Family of Writers. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2007, ISBN 978-0-8018-8618-8 , p. 2.

- ↑ St Clair, 179-188; Seymour, 31-34; Clemit: Legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft. (CC), 27-28.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 38, p. 49; St. Clair, pp. 255 to p. 300

- ↑ St Clair, pp. 199 to 207

- ↑ Claire Clairmont's maiden name was Jane Clara Clairmont; but from 1814 she called herself Claire and under this name she went down in literary history. Throughout the article, she is referred to as Claire Clairmont

- ^ Todd: Death and the Maidens. Pp. 56-58; Holmes: Shelley: The Pursuit. P. 170; St Clair, p. 241.

- ^ Letter to Percy Shelley, October 28, 1814. In: Selected Letters , 3; St Clair, p. 295; Seymour. P. 61.

- ↑ Pechmann, p. 35.

- ^ Todd: Death and the Maidens. P. 61; St Clair, pp. 284-286, pp. 290-296.

- ^ Todd: Death and the Maidens. Pp. 61-62, 66-68.

- ↑ Pechmann, pp. 18, 34; Bennett: An Introduction. Pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 53.

- ^ Priest, p. 37.

- ↑ Priest, p. 42.

- ^ Sunstein, p. 58; Spark, p. 15.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Spark, p. 17.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 69.

- ^ Todd: Death and the Maidens , pp. 9, p. 133.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 66-70; S. St. Clair, pp. 329-335.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 107.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 78-79; Pechmann, pp. 40-47.

- ↑ quoted from Pechmann, p. 47.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 90.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 19-22; St Clair, p. 358.

- ^ Todd: Death and the Maidens , pp. 9, 133; St. Clair, p. 355.

- ^ Letter to Maria Gisborne, written between October 30 and November 17, see Seymour, p. 49.

- ↑ Spark, p. 24; Seymour, pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Quoted from Sunstein, p. 84

- ↑ Spark, pp. 26-30.

- ^ Bennett: An Introduction. P. 20; St Clair, p. 373; Sunstein, pp. 88-89; Seymour, pp. 115-116.

- ^ Pechstein, p. 59.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 36-37; St Clair, p. 374; Pechstein, p. 61.

- ^ Pechstein, p. 61.

- ↑ The original quote is: “ Very Unwell. Shelley & Clary walk out, as usual, to heaps of places… A letter from Hookham to say that Harriet has been brought to bed of a son and heir. Shelley writes a number of circular letters on this event, which ought to be ushered in with ringing of bells, etc., for it is the son of his wife . ”

- ↑ Spark, pp. 38-44.

- ↑ St Clair, p. 375.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 41-46; Seymour, pp. 126-127; Sunstein, pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Sunstein, pp. 98-99.

- ^ Pechstein, p. 65.

- ↑ St Clair, p. 375; Spark, pp. 45, 48.

- ^ Pechstein, p. 64

- ↑ Sunstein, pp. 93-94, 101; Seymour, pp. 127-128, 130.

- ↑ Gittings and Manton, pp. 28–31; Seymour, pp. 146-153.

- ↑ Gittings, Manton, p. 31; Seymour, p. 152.

- ^ Priest, p. 105.

- ↑ 1816 has gone down in climate history as the year without a summer : The effects of the Tambora volcanic eruption in Indonesia led to a summer in England and Western Europe that was unusually cold and rainy.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 328; and Mary Shelley's foreword to Frankenstein from 1831.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 157-161.

- ↑ Sunstein, pp. 124–125; Seymour, p. 165.

- ↑ St Clair, p. 413; Seymour, p. 175.

- ↑ priests, S. 144- 145th

- ↑ Graham Allen: Mary Shelley. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 0-23001908-0 , p. 4.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 195-196.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 57, 60-62; Seymour, pp. 177, 181-192. The birth name was originally Alba Byron.

- ↑ Gittings and Manton, pp. 39-42; Spark, pp. 62-63; Seymour, pp. 205-206.

- ^ Bennett: An Introduction , p. 43.

- ↑ Sunstein, pp. 170-171, 179-182, 191.

- ↑ Quoted from Seymour, p. 233.

- ^ Bennett: An Introduction. Pp. 47, 53.

- ↑ Spark, p. 72; Sunstein, pp. 384-385.

- ^ Bennett: An Introduction. P. 115.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 251.

- ↑ Bieri, pp. 170-176; Seymour, pp. 267-270, pp. 290; Sunstein, pp. 193-195, pp. 200-201.

- ^ Bennett: An Introduction , pp. 43-44; Spark, pp. 77, 89-90; Gittings and Manton, pp. 61-62.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 464; Bieri, pp. 103-110.

- ↑ Gittings and Manton, p. 46; Seymour, pp. 221-222.

- ↑ Spark, p. 73; Seymour, p. 224; Holmes, pp. 469-470.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 221; Spark, p. 86; Letter to Isabella Hoppner, August 10, 1821 in: Selected Letters , pp. 75–79.

- ↑ Journals , pp. 249-250, footnote 3 , Seymour, p. 221; Holmes, pp. 460-374; Bieri, pp. 103-112.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 466; Bieri, p. 105.

- ↑ Spark, p. 79; Seymour, p. 292.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, p. 71.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 725; Sunstein, pp. 217-218; Seymour, pp. 270-273.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 728.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 302-307.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 100-104.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 102-103; Seymour, pp. 321-322-

- ↑ Spark, pp. 106-107; Seymour, pp. 336-337; Bennett, An Introduction. P. 65.

- ↑ Graham Allen: Mary Shelley. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 0-23001908-0 , p. 3.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 362.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 341, 363, 365.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 111-113; Seymour, pp. 370-371.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 117-119.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 384-385.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 389-390.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 404, 433-435, 438.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 406.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 450, 455.

- ^ Seymour, p. 453.

- ↑ Graham Allen: Mary Shelley. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 0-23001908-0 , p. 3.

- ^ Seymour, p. 465.

- ↑ See Bennett, Introduction to Selected Letters , xx, and Mary Shelley's letter of May 24, 1828, and the accompanying notes by Bennett, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Spark, p. 122.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 401-402, 467-468.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 133-134; Seymour, pp. 425-426; Bennett, Introduction to Selected Letters , xx.

- ↑ Spark, p. 124; Seymour, p. 424.

- ↑ Spark, p. 127; Seymour, pp. 429, 500-501.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 489.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 495.

- ↑ Spark, p. 140; Seymour, pp. 506-507.

- ↑ Spark, pp. 141-142; Seymour, pp. 508-510.

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 515-516; Bieri, p. 112.

- ↑ Spark, p. 143; Seymour, p. 528.

- ↑ Spark, p. 144; Bennett, Introduction to Selected Letters , pp. Xxvii.

- ↑ Sunstein, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Bennett, "Mary Shelley's letters" (CC), pp. 212 to 213.

- ^ Mary Shelley, Introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein .

- ↑ Nora Crook, "General Editor's Introduction," Mary Shelley's Literary Lives , Vol. 1, pp. Xiv.

- ↑ Sussman, 163; St Clair, 297; Sunstein, 42.

- ↑ Seymour, p. 55; Carlson, p. 245; "Appendix 2: 'Mounseer Nongtongpaw': Verses formerly attributed to Mary Shelley", Travel Writing: The Novels and Selected Works of Mary Shelley , Vol. 8, Ed. Jeanne Moskal, London: William Pickering (1996).

- ↑ Allen, pp. 43-45

- ↑ Allen, p. 65.

- ^ Allen, p. 118

- ↑ Allen, p. 90

- ^ Allen, p. 139

- ^ Allen, pp. 142--145

- ^ Allen, p. 161.

- ↑ Graham Allen: Mary Shelley , palgrave macmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 0230019080 , pp. 41-43

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction , 74; Lokke, "The Last Man" (CC), 119.

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , S. 190th

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , p 191

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , pp. 190 to 192; Clemit, "From The Fields of Fancy to Matilda, " pp. 64 to 75; Blumberg, pp. 84 to 85.

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , pp. 140 to 141, p. 176; Clemit, "Legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft" (CC), p. 31

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , S. 143-S. 144; Blumberg, p. 38 to p. 40

- ^ Mellor, "Making a 'monster'" (CC), 14; Blumberg, 54; Mellor, 70.

- ↑ Blumberg, p. 47 and Mellor, p. 77 to p. 79

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , p 144

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , S. 187 and S. 196

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction , pp. 36 to 42.

- ↑ Blumberg, p. 21

- ↑ Blumberg, p. 37, p. 46, p. 48; Mellor, p. 70 to p. 71, p. 79.

- ↑ Lokke, "The Last Man" (CC), S. 116 and S. 128; see also Clemit, Godwinian Novel , p. 197 to p. 198.

- ↑ Curran, "Valperga" (CC), pp. 106-107; Clemit, Godwinian Novel , p. 179; Lew, "God's Sister" (OMS), pp. 164-165

- ↑ Clemit, Godwinian Novel , p 183; Bennett, "Political Philosophy," p. 357

- ↑ Lew, "God's Sister" (OMS), pp. 173 to 178.

- ↑ Bunnell, p. 132; Lynch, "Historical novelist" (CC), pp. 143-144; Lew, "God's Sister" (OMS), pp. 164-165

- ^ Sussman, "Stories for The Keepsake " (CC), p. 163

- ↑ Sussman, "Stories for The Keepsake " (CC), pp. 163 to 165.

- ↑ In the original the full quote is: "I write bad articles which help to make me miserable — but I am going to plunge into a novel and hope that its clear water will wash off the mud of the magazines." quoted from Bennett, An Introduction , p. 72

- ↑ Moskal, "Travel writing" (CC), p. 242

- ↑ Moskal, "Travel writing", pp. 247 to 250

- ^ Nora Crook, "General Editor's Introduction," Mary Shelley's Literary Lives , Vol. 1, xix

- ↑ Kucich, "Biographer" (CC), p 227 to p 228

- ↑ Nora Crook, "General Editor's Introduction," Mary Shelley's Literary Lives , Vol. 1, xxvii; Tilar J. Mazzeo, "Introduction by the editor of Italian Lives ", Mary Shelley's Literary Lives , Vol. 1, xli.

- ↑ Kucich, "biographer" (CC), the 236th

- ↑ Kucich, "Biographer" (CC), pp. 230-231, pp. 233, p. 237; Nora Crook, "General Editor's Introduction," Mary Shelley's Literary Lives , Vol. 1, xxviii; Clarissa Campbell Orr, "Editor's Introduction French Lives, " Mary Shelley's Literary Lives , Vol. 2, lii.

- ↑ Kucich, "biographer" (CC), p 235

- ↑ Spark, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ Wolfson, "Mary Shelley, editor" (CC), p. 193, p. 209; Bennett, An Introduction , p. 112; Fraistat, "Shelley Left and Right," Shelley's Prose and Poetry , p. 645.

- ^ Wolfson, "Mary Shelley, editor" (CC), p. 193

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction , pp. 111-p. 112.

- ↑ Fraistat, "Shelley Left and Right," Shelley's Prose and Poetry , p 645 to p 646; and Seymour, p. 466; Wolfson, "Mary Shelley, editor" (CC), pp. 195, pp. 203.

- ^ Wolfson, "Mary Shelley, editor" (CC), p. 194; Fraistat, "Shelley Left and Right," Shelley's Prose and Poetry , p. 647

- ^ Wolfson, "Mary Shelley, editor" (CC), p. 203

- ^ Wolfson, "Mary Shelley, editor" (CC), p. 198

- ↑ Seymour, p. 466; Blumberg, pp. 160-161, pp. 169-p. 170.

- ↑ Blumberg, p. 156

- ^ Wolfson, "Editorial Privilege" (OMS), p. 68

- ↑ Seymour, pp. 467- 468; Blumberg, p. 165 to p. 166.

- ↑ Bennett, "Finding Mary Shelley", pp. 300 to 301; Bennett, An Introduction , p. 110

- ↑ Mellor, xi, p. 39.

- ^ Allen, p. 1.

- ^ Allen, p. 1.

- ↑ Quoted in Blumberg, p. 2. The original quote is: a collection of the present size could not be justified by the general quality of the letters or by Mary Shelley's importance as a writer. It is as the wife of [Percy Bysshe Shelley] that she excites our interest.

- ↑ Bennett: Finding Mary Shelley. P. 291. The original quote is: the fact is that until recent years scholars have generally regarded Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley as a result: William Godwin's and Mary Wollstonecraft's daughter who became Shelley's Pygmalion.

- ^ "Introduction" (OMS), p. 5

- ↑ Hoeveler, " Frankenstein , feminism, and literary theory" (CC), p 46

- ↑ Hoeveler, " Frankenstein , feminism, and literary theory" (CC), pp. 46 to 47; Mellor, pp. 40-51.

- ↑ Gilbert and Gubar, p. 220 - in the original the quote is conceals fantasies of equality that occasionally erupt in monstrous images of rage ; also Hoeveler: "Frankenstein." feminism, and literary theory. (CC), pp. 47-48, 52-53.

- ^ Bennett: Finding Mary Shelley. Pp. 292-293.

- ^ Bennett: An Introduction. S. ix-xi, 120-121; Schor: Introduction to "Cambridge Companion". Pp. 1-5; Seymour, pp. 548-561.

- ^ Mary Shelley in the Science Fiction Awards + Database .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Shelley, Mary |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft; Godwin, Mary (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 30, 1797 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 1, 1851 |

| Place of death | London |