Malignant melanoma

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C43 | Malignant melanoma of the skin |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The malignant melanoma (from ancient Greek μέλας "black"), also briefly melanoma , Melano (cyto) blastoma or black skin cancer ( English :. [Malignant] melanoma ), is a highly malignant tumor of pigment cells (melanocytes). It tends to spread metastases via the lymphatic and blood vessels early on and is the most common fatal skin disease with a rapidly increasing number of new cases worldwide .

In addition to the malignant melanoma of the skin (cutaneous melanoma) treated here, there are also malignant melanomas of the mucous membranes ( mucosal melanoma ), the eye (conjunctival melanoma, choroidal melanoma ), the central nervous system , the internal organs and the anus ( anorectal melanoma ). This group of malignant melanomas is called mucosal melanomas (from mucosa = mucous membrane). Compared to cutaneous melanoma, mucosal melanomas are much rarer.

frequency

The frequency of new cases ( incidence ) in the fair-skinned population in Europe and North America is around 13 to 15 new cases per year for every 100,000 inhabitants. This results in a lifetime risk of a little more than one percent. For comparison, the lifetime risk of colorectal cancer is 4 to 6 percent. The incidence of this disease has increased dramatically over the past 50 years. In 1960 the lifetime risk was still 1: 600, while it is currently in the range from 1:75 to 1: 100. These values make malignant melanoma the tumor with the fastest increasing incidence.

In 2010, 19,220 people (9,640 men and 9,580 women) in Germany developed malignant melanoma of the skin. In the same year, 2,711 Germans (1,568 men and 1,143 women) died as a result of this disease. For 2014, 19,700 new cases were forecast. The mean age of onset for women is 58 and for men 66 years. Both the disease rate and the death rate are slightly higher in men than in women.

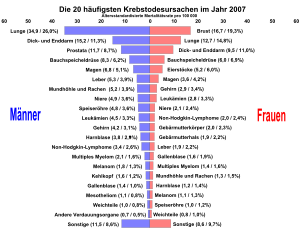

As the cause of death, malignant melanoma accounts for 1.3 percent of all causes of cancer death in Germany for both sexes. Education programs have kept the death rate largely constant - despite a significant increase in the number of illnesses.

The frequency of malignant melanoma of the skin varies greatly from region to region. In some states it is an extremely rare disease, while in the fair-skinned population of Australia the lifetime risk - compared to Europeans - is about four times higher and is around four percent. In North America, in the age group 25 to 34, melanoma is the fourth most common cancer in men and the second most common cancer in women. The world's highest value is reached in Auckland ( New Zealand ). African Americans are 20 times less likely to develop malignant skin melanoma than people with fair skin.

Risk factors

Tabular summary

The following are considered risk factors:

- previous malignancy

- Fair skin, red and blonde hair, light eye color

- high number of common melanocytic nevi (birthmarks)

- Immunosuppression

- intermittent intense exposure to UV light

- congenital melanocytic nevus, especially a huge one

- several atypical melanocytic nevi

- Melanoma in the Family

- Tendency to sunburn upon exposure to UV light

- Freckles, actinic lentigines

- DNA repair disorders, particularly xeroderma pigmentosum

UV radiation and sunburn

The number of patients suffering from melanoma doubles every seven years. In the past, this was primarily attributed to changes in leisure habits. UV radiation is considered to be the most important environmental cause of melanoma. The connection between solar radiation and the incidence of cancer was first demonstrated by Eleanor Josephine Macdonald on the basis of the cancer registry she set up in the USA .

"Despite many awareness-raising campaigns" in the last two decades, the ideal of beauty "being brown = being healthy" has "not yet been corrected sufficiently", so that "the number of new diseases continues to rise every year" despite increased health awareness.

The German Cancer Research Center regards excessive exposure to sunlight as a major environmental risk factor. In addition, the skin type plays a decisive role as an endogenous factor. Statistically speaking, redheads who have skin that is particularly sensitive to UV radiation are 4.7 times more likely to develop malignant melanoma than black-haired people.

The search for possible occupational risk factors - like nutritional epidemiological studies - yielded contradicting results.

Influence of sunscreen

The protective effect of sun creams is very controversial. There are very contradicting studies on preventing skin cancer from developing. Some studies have found more negative effects from using sunscreens, while other publications and studies claim the opposite. In the animal model, a clear effect of sunscreen to prevent the formation of a spinalioma of the skin (a squamous cell carcinoma ) was determined, but this is not the case with malignant melanoma and basalioma .

In a meta-study published in 2003 , however, no connection was found between the use of sunscreen and the increase in malignant melanoma diseases in humans. The study comes to the conclusion that in previous studies errors had obviously been made in taking into account the effects of confusion and therefore they found a positive correlation between the use of sunscreen and the occurrence of malignant melanoma. One speaks of confusion effects when the phenomenon to be investigated (here the increase in malignant melanomas) is influenced by two or more conditions at the same time. In the previous studies, newer sun creams with a protection factor greater than 15, protection against UV-A radiation and water resistance were not considered at all. The authors believe that it can take decades to determine a positive effect between the use of newer sunscreen formulations and malignant melanoma.

A study published in Nature in 2014 suggests that sunscreen does not provide adequate protection against malignant melanoma. In the study, the shaved backs of mice in which a certain mutation in the growth gene BRAF had been artificially induced were repeatedly exposed to a dose of ultraviolet radiation that would correspond to mild sunburn in humans. Completely unprotected areas of the skin developed melanomas within seven months, areas of skin treated with sun protection factor 50 remained without melanoma for up to 17 months, and areas covered with a cloth remained melanoma-free for at least two years to about 20 percent.

Pigment nevus

The majority of melanomas develop de novo, that is, on previously healthy skin. There is no evidence that damage to a nevus, such as from injury, can lead to the development of malignant melanoma. On average, a person has about 20 nevi all over their skin. People with over 50 nevi are 4.8 times more likely than people with fewer than 10 nevi on their skin to develop malignant melanoma in their lifetime. The number of melanocytic nevi is therefore an important risk factor for malignant melanoma. In 30 to 40 percent of cases there is an association between melanocytic nevi and malignant melanoma. People who have a high number of nevus cell nevi and are carriers of dysplastic nevus cell nevi have an increased risk of developing malignant melanoma during their lifetime.

About five to ten percent of all malignant melanomas occur in families. A polygenic inheritance is suspected here.

genetics

Even if the majority of melanomas develop spontaneously, there is a familial cluster in 10–15% with autosomal dominant inheritance with variable penetrance .

The most common mutations in melanoma cells affect cell cycle control , signaling pathways of cell growth and differentiation, and telomerase .

Mutations in the CDKN2A gene are found in 40% of autosomal dominant inherited melanomas , the gene products of which (p15 / INK4b, p16 / INK4a and p14 / ARF) act as tumor suppressors by stopping the cell cycle in the G 1 phase.

There are also mutations that affect the RAS and PI3K / AKT signaling pathways that regulate cell growth.

In the spontaneous form of melanoma, a mutation in the TERT gene is found in 70% of tumors, which encodes the catalytic subunit of telomerase .

Diagnosis

Warning symptoms of malignant melanoma can include enlargement, change in color and itching of pigment nevi ( moles ) (40% of diseases cause moles) or changes in areas of the skin that are pigmented (appear darker). In dark-skinned people, on the other hand, the disease usually starts in areas that are less dark, for example the mucous membranes or the palms of the hands.

early detection

Any suspicion should be clarified by a dermatologist as soon as possible so that the melanoma can be removed early - before metastasis - if necessary. In Germany, the offer health insurance to the statutory health insurance therefore by Decision of the Joint Federal Committee (GBA) of 15 November 2007 since 1 July 2008, a skin cancer screening without incident light microscopy , and as from the age of 35 every two years. However, the German Dermatological Society recommends having the skin examined by a dermatologist once a year with a reflected light microscope if there are abnormal moles. This more informative examination is not explicitly taken over by a health insurance company, so that it is often billed privately according to GOÄ . Regular self-exams for changes in moles will help detect melanoma early. This is especially important for those with relatives with melanoma or with a variety of nevus cell nevi . Melanoma can also develop in hidden places, such as the ear, in the anal area or between the toes.

Assessment according to the "ABCDE rule"

If two of the following five criteria apply to a suspicious pigment spot, it is usually advisable to remove the spot as a precautionary measure:

- A - Asymmetry: not symmetrical, for example not round or oval

- B - Border: irregular or fuzzy

- C - Color: pigmentation of different strengths, multicolor

- D - earlier diameter (diameter) - greater than 5 mm - today dynamics (progression): Relation to growth and time

- E - evolution (sublimity / development): new and emerged in a short time on otherwise flat ground

diagnosis

A doctor with appropriate experience can usually determine whether it is malignant melanoma or not by inspecting the suspicious skin area. In case of doubt, the suspicious skin area is removed as a whole ( in toto ) with an appropriate safety margin and examined under the microscope. Smaller tissue samples should only be taken if a complete excision is difficult and one has doubts about the benignity, since the entire lesion should be assessed for the fine-tissue diagnosis or to determine the tumor thickness . In addition, it is controversial whether removing only a small portion of the tumor would increase the risk of spreading ( metastasis ) via the bloodstream or the lymph. More on this topic below.

Depending on the tumor stage, further expansion diagnosis ( staging ) is carried out by means of ultrasound of the neighboring lymph node stations , examination of the sentinel lymph node or computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the skull . In addition, positron emission tomography (PET) is particularly suitable for diagnosing metastases , staging and re-staging of malignant melanoma , especially in cases of doubt . However, the statutory health insurance companies do not assume any costs.

Other supporting diagnostic methods include, for example, the electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) method described in a pivot study published in 2014 and developed at the Stockholm Karolinska Institute , which, with a sensitivity of 97%, can be used as an aid for the early detection of melanomas. The EIS procedure enables a painless and non-invasive examination of suspicious skin areas up to a depth of 2.5 mm. EIS is also suitable for excluding a suspected melanoma in clinically conspicuous lesions, so that it can help avoid unnecessary excisions.

The examination of the autofluorescence of the skin ( dermatofluoroscopy ) is not yet a part of the routine diagnostics : This makes it possible to check the clinical diagnosis in vivo at an early stage . For this, the skin is irradiated with infrared laser light in short pulses. The melanin molecule absorbs two of the photons and fluoresces in the red or blue-green spectral range. Based on the color, a decision can be made about the malignancy of the pigment spot examined. Initial studies show that this fluorescence method ensures reliable melanoma detection in the smallest of lesions. On the other hand, the finding of “benign nevus” can be ascertained with it just as reliably. In this way, the large number of precautionary tissue removals in the clinical diagnosis of “atypical / dysplastic nevus” could be avoided in the future. The simple possibility of in vivo progress controls offers additional security for doctor and patient.

In the case of melanoma patients, the results of the liquid biopsy can be helpful as novel predictive biomarkers in therapeutic decisions, especially in connection with mutation-based, targeted therapies.

Subtypes of malignant melanoma

| Subtype | abbreviation | percentage share |

median age of onset |

| superficial spreading melanoma | SSM | 57.4% | 51 years |

| nodular malignant melanoma | NMM | 21.4% | 56 years |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | LMM | 8.8% | 68 years |

| acral lentiginous melanoma | ALM | 4.0% | 63 years |

| unclassifiable melanoma | UCM | 3.5% | 54 years |

| Others | 4.9% | 54 years |

Another subspecies, amelanotic melanoma (AMM), is a very rare variant and is included in the table above under “Other”.

These subtypes differ in their appearance, the type of growth and their tendency to metastasize. They have different prognoses . Since the classification is not necessarily clear just by looking at it, a histological examination is carried out in all cases after the tumor has been surgically removed .

Malignant melanoma metastasize particularly aggressively. Cases have been reported where the malignant melanoma has metastasized to other malignant tumors. Because of this strong tendency to metastasize, it is also forbidden to take a tissue sample ( biopsy ). Instead, the change must be removed completely and with a sufficient safety margin.

Superficial Spreading Melanoma (SSM)

The most common form of malignant melanoma, superficial (superficial) spreading melanoma, grows slowly, usually over a period of two to four years, horizontally in the skin plane. It manifests as an irregularly pigmented, indistinctly delineated spot. Depigmented (light) islands can arise in the center. In the later stage, after about two to four years, the SSM also grows in a vertical direction and protrusions are formed. In women, the SSM is often found on the lower leg, in men mostly on the trunk. It usually develops after the age of 50.

Nodular Malignant Melanoma (NMM)

Nodular malignant melanoma is the most aggressive form of malignant melanoma with the worst prognosis. It occurs more frequently from the age of 55. It is characterized by its relatively rapid vertical growth and its early metastasis via lymph and blood. It is brown to deep black in color with a smooth or ulcerated surface that bleeds easily. The nodular melanoma can also be amelanotic, i.e. no longer able to produce melanin . It is then called amelanotic melanoma (AMM), as described below. Most often the tumor appears on the back, chest, or extremities. In the absence of melanin synthesis, it can often be misdiagnosed.

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma (LMM)

Lentigo maligna precedes the LMM . It grows relatively slowly and initially mainly radially and horizontally. Vertical growth only occurs after up to 15 years, which is why the tendency to metastasize is lower and the prognosis is therefore more favorable. Its appearance is characterized by large, sometimes raised, irregular spots. 90% of the LMM are located on the face, mostly in older people from the age of 65.

Acrolentiginous Melanoma (ALM)

The appearance of acrolentiginous melanoma is similar to the appearance of the LMM, but it grows much faster and more aggressively. This tumor is usually located on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet, but also under the nails. It is prone to bleeding and, if placed under a fingernail or toenail, can lead to nail peeling. This type of melanoma prefers dark-skinned people. In Africa and Asia, it accounts for the majority of melanoma diagnoses at 30 to 70 percent. Acrolentiginous melanoma is particularly demanding in the differential diagnosis, since it is often amelanotic and the prognosis is rather unfavorable.

Amelanotic melanoma (AMM)

The amelanotic melanoma roughly corresponds to the NMM, but due to the degeneration of the cells, no pigment is formed any more. This makes it particularly treacherous because it is often discovered very late; then metastases are often already present. Amelanotic melanomas can look very unusual.

Rare variants of melanoma

Polypoid melanoma

Polypoid melanoma is a special variant of malignant melanoma, both histologically and clinically. It occurs in a stalked shape and has a cauliflower-like shape. It grows for the most part beyond the surface of the epidermis (exophytic) and the nodes are in most cases amelanotic. Polypoid melanoma is often localized on the back.

pathology

The diagnosis of malignant melanoma is based on the histological examination (tissue examination under the microscope) of clinically conspicuous pigment marks and should be made against the background of clinical information. In addition to the patient's age and clinical appearance of the lesion, the site where the tissue sample was taken and, if necessary, information on the rate of growth or a change in color should also be taken into account.

In order to be able to histologically assess all the features required for classification as a benign or malignant lesion, pigment marks should be removed as completely as possible. A distance from the lesion to the incision margin of two millimeters and a distance into the subcutis (the subcutaneous fatty tissue ) are recommended. In cases of large or inaccessible lesions with severe cosmetic or functional impairment due to complete removal, e.g. B. acral (on the hands and feet) or on the face, a partial removal can be done first. If the histological examination reveals the diagnosis of malignant melanoma, a safety margin appropriate to the tumor thickness must be created by re-excision, if necessary.

Even if the lesions have been completely removed and all necessary information is known, the histological differentiation of malignant melanomas from benign nevi can be made more difficult by overlapping features of both lesions. Various criteria are to be evaluated and, depending on the constellation and degree of severity of the changes, lead to the final classification as benign or malignant lesion.

Histological features of malignant melanoma

architecture

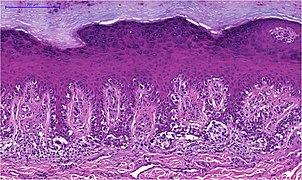

Melanomas vary in size between one millimeter and several centimeters. Although benign nevi occasionally reach a diameter of several centimeters, in case of doubt a large area of a pigment mark speaks for malignancy. Even the depth of pigment lesions alone does not allow a reliable statement about benign or malignancy, since both nevi and melanomas can grow purely superficially or in depth. Very early melanomas in the horizontal growth phase initially grow in situ (Latin: on site) within the epidermis (epidermis). In the vertical growth phase, the melanocytes break through the basement membrane (border between epidermis and dermis or dermis) and grow invasively in depth. An expansion into deep layers of the dermis or into the subcutis is in turn an indication of malignancy.

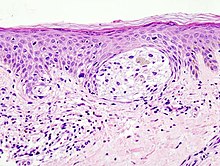

Another criterion in the histological assessment of pigment marks is the distribution of the melanocytes. In in situ melanomas, they are distributed as single cells or in small nests mostly along the junction zone (border between epidermis and dermis , this is where the basement membrane is located) in the basal cell layer (bottom cell layer) of the epidermis. This can lead to the impression of a chain-like lining up of the melanocytes with complete replacement of the basal cell layer. Irregular and increasing distances between small melanocyte nests or single melanocytes in the edge area of the lesion form the histological equivalent of the clinically mostly irregular or fuzzy delimitation of melanomas, while the sharp delimitation by large melanocytic nests indicates a benign lesion.

The storage of melanocytes in the upper cell layers of the epidermis, known as pagetoid, is also considered a criterion for a malignant lesion. Although this phenomenon also occurs in benign nevi if they are irritated by scratching or UV radiation, it is then mostly restricted to the center of the lesion and does not reach the topmost cell layer. In the case of melanoma, the edge of the lesion and the entire width of the epidermis are also affected.

As the size increases, the melanocytes show a stronger tendency to cluster in the epidermis to form nests, which in turn can cluster together to form larger associations. Nests in the horizontal growth phase are roughly the same size, while dermal nests in the vertical growth phase tend to be larger.

The criterion of symmetry is also used not only clinically but also histologically. This feature refers less to the outline of the tumor, which is mostly irregular, especially at the base (location of the greatest penetration depth), but to its cell density and the distribution pattern (single-cell or in nests) and the cell structure (uniform or variable) Melanocytes. If these features differ significantly when compared to the side of the lesion, this is considered indicative of a malignant lesion. Differences in the melanin content of the melanocytes, the nature of the epidermis and the density of the accompanying inflammatory infiltrate can also be assessed in this way, but are less important in their evaluation than the factors mentioned above.

Texture of the epidermis

In contrast to benign nevi, melanomas often have an irregular contour of the epidermis. Melanomas also tend to ulceration (ulceration to the underlying dermis), while defects in epidermal nevi generally to mechanical irritation, z. B. scratching, are due.

As typical of melanomas also in the English language as valid Consumption designated (ger .: shrinkage) phenomenon of atrophy (tissue shrinking) of the epidermis with flattening both the rete pegs and the keratinocytes (horn-forming cells of the epidermis) in the basal cell layer. This change is often found in the marginal area of ulcerations and is therefore considered a preliminary stage.

cytology

The cell picture is less important for the assessment of melanoma than it is for other tumors. Nevertheless, some features can be used to differentiate the individual melanoma types and to differentiate them from benign nevi.

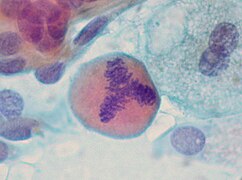

The epidermal component of invasive melanomas of all subtypes often contains large, rounded, oval melanocytes with an abundant pale, powdery-pigmented cytoplasm. Spindle-like cell shapes also occur, but unlike in nevi they each have a different orientation (alternating more or less perpendicular or parallel to the epidermis). The melanocytes are similar within the horizontal growth phase. Melanocytes in the vertical growth phase, especially in deeply invasive melanomas and in melanoma metastases (daughter tumors), on the other hand, are usually multifaceted with large, irregularly contoured and strongly eosinophilic (reddish in the hematoxylin-eosin staining ) nucleoli .

Within the dermal component, all invasive melanomas have in common the extensive cytological uniformity of superficial and deeper parts. There is no deep maturation of the melanocytes, which is evident in benign nevi when both the melanocytic nests and the individual melanocytes including the cell nuclei and nucleoli become smaller, as well as a decrease in the degree of pigmentation of the cytoplasm .

- Cell forms of malignant melanoma

Mitotic activity

Corresponding to the mostly rapid growth of malignant tumors, melanomas show an increased rate of cell division and thus increased mitoses (cell division figures). While mitoses in benign nevi only appear in the superficial parts of the dermal component, in melanomas these are also found at the base of the dermal component. A focal accumulation in hot spots (areas of high mitotic activity) also indicates malignancy, as does atypical, i.e. asymmetrical, tripolar or ring-shaped mitotic figures.

- Mitoses

Regression

The phenomenon of regression describes the death of malignant cells of a tumor with the result that the tumor regresses partially or completely. The partial (partial) regression of the malignant melanoma shows a significantly reduced content of tumor cells within a certain area compared to the rest of the tumor. The complete disappearance of certain areas with the formation of completely tumor-free islands within the residual tumor is called segmental regression. Instead of the submerged tumor tissue and in the adjacent dermis, there is a circumscribed fibrosis (increase in connective tissue), an increase and ectasia (expansion) of small blood vessels and an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes (sub-form of white blood cells) and melanophages (pigment-storing phagocytes ). The rete cones of the overlying epidermis are flattened. While this picture of regression is usually shown in melanomas in the horizontal growth phase, tumor-free areas are occasionally found in the vertical growth phase, which are completely replaced by accumulations of melanophages.

Subtypes of malignant melanoma

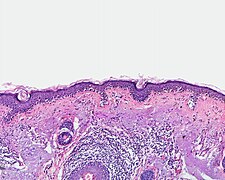

Lentigo maligna melanoma

On sun-damaged skin, malignant melanomas usually develop on the base of a melanoma in situ initially limited to the epidermis, the lentigo maligna . It consists of a predominantly single-cell spread of atypical melanocytes along the junction zone and of adnexal structures (skin appendages) against the background of an atrophic (narrowed) epidermis and elastotic (sun-damaged) dermis. With the transition to an invasively growing melanoma, one speaks of lentigo maligna melanoma. The dermal component shows a low penetration depth, corresponding to its predominantly horizontal growth.

The melanocytes in lentigo maligna as well as in lentigo maligna melanoma are mostly small and have hyperchromatic (excessively stained), angled-appearing cell nuclei. The degree of pigmentation of the cytoplasm can vary widely within a lesion.

Melanocytes with conspicuous dendrites (cytoplasmic extensions) are also often found , especially in fair-skinned patients. An expansion of the dendrites into the middle stratum spinosum and a clear anisodendrocytosis (width variance of the dendrites) are indicative of malignancy.

More often than in other invasively growing melanomas, a spindle cell structure of the dermal component is shown in the lentigo maligna melanoma. The tumor cells spread individually or in some cases in strand-like associations in the upper dermis. This shows a desmoplastic reaction (tumor-induced connective tissue formation) and an inflammatory infiltrate rich in lymphocytes and melanophages .

- Lentigo maligna (melanoma in situ)

Superficial spreading melanoma

The superficial spreading melanoma occurs in covered skin, usually not exposed to sunlight. Previous sunburns in childhood and repeated exposure to sunlight in adulthood are nevertheless causally significant. The tumor grows predominantly horizontally, initially as a melanoma in situ limited to the epidermis. The epidermal component is usually broad and indistinct, but sharply delimited lesions with clinically irregular contours can also occur.

The melanocytes have large cell nuclei, which often also have enlarged nucleoli. Mitoses are rare in the epidermal component. The cytoplasm is usually large and the pigment content can vary widely within a lesion. The tumor cells spread individually or in irregular, sometimes interconnected nests in the epidermis, following adnexal structures. Typical of the superficial spreading melanoma is the growth pattern known as pagetoid: atypical melanocytes are not only found along the junction zone, but are distributed over the entire width of the epidermis down to the superficial cell layers.

The dermal component of superficial spreading melanomas is usually asymmetrical. There is no maturation of the melanocytes and mitoses are found. Necrotic (dead) melanocytes are rarely seen. At the base of the tumor and possibly also between the tumor cells, there is a mainly lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate.

- Superfilamentous spreading melanoma

Nodular melanoma

Due to its early vertical growth, this form of melanoma quickly reaches a great depth. Its development from a benign melanocytic nevus is considered rare, rather the nodular melanoma is assumed to be the common end state of initially superficially growing melanomas with a short horizontal growth phase.

According to its nodular (nodular) configuration, histologically a hemispherical protruding, often asymmetrically arranged tumor is shown, which is covered by a flattened, often ulcerated epidermis. If the epidermis is preserved, it usually has an epidermal melanoma component which, depending on the doctrine, does not protrude laterally over the dermal component or at most over three adjacent rete cones.

The dermal component consists of a solid, nodular bandage or small nests of atypical melanocytes with displacing growth downwards. The cells are mostly large and rounded, but spindle cells, small nevus-like cells and multinucleated giant cells also occur. Although the tumor cells can appear relatively uniform at low magnification, variable cell nuclei with clearly visible nucleoli appear at high magnification in terms of size, shape and chromatin content (chromatin: basic genetic material of the cell nucleus). Mitoses are also found in deep parts of the dermal component. The cytoplasm content of the melanocytes is low in relation to the size of the nucleus, and the cytoplasm contains melanin granules of various sizes or also known as powder-like granules. There is no deep maturation of the melanocytes.

In the adjacent dermis there is a more or less dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and melanophages, fibroplasia (formation of fibrous connective tissue) and dilated blood vessels.

- Nodular melanoma

Acrolentiginous melanoma

In view of its origin on the palm of the hand or the soles of the feet, sunlight does not seem to be the cause of this type of melanoma, or only to be of minor importance.

In the horizontal growth phase there is an increase in melanocytes limited to the epidermis, which are mostly large and also have significantly enlarged, occasionally bizarre cell nuclei. The cytoplasm contains melanin granules in varying amounts and shapes, and tumor cells located in the basal epidermis, in particular, often have conspicuous dendrites. The atypical melanocytes spread in single-cell storage along the junction zone and in depth along the excretory ducts of the sweat glands.

In tumors that have existed for a longer period of time, there is also an increasing number of large melanocyte nests along the junction zone and single melanocytes or melanocytes stored in nests in the upper cell layers of the epidermis, possibly with discharge through the overlying enlarged horny layer . The epidermis showed acanthosis (widening) and elongated rete cones.

In the vertical growth phase, spindle-cell melanocytes are often found in the dermis. The latter shows a desmoplastic reaction.

- Acrolentiginous melanoma

Other types of melanoma

In addition to the four types of malignant melanoma listed, there are other, rare variants. Examples are the nevoid (nevus-like) melanoma with small, round melanocytes, as well as the desmoplastic melanoma with narrow, spindle-shaped melanocytes and a conspicuous desmoplastic reaction of the dermis.

Amelanotic (non-pigmented) melanoma is a clinical variant that does not enter the WHO histological classification. In principle, all types of melanoma can also occur as amelanotic tumors.

- Other types of melanoma

classification

The TNM classification is used to classify malignant tumors from a prognostic point of view (relating to the probable course of the disease) depending on their size and local extent (T) and the presence of lymph nodes (N) and distant metastases (M).

To determine the T category of malignant melanoma, according to the AJCC classification of 2016, in addition to the tumor thickness according to Breslow, the ulceration criterion is used. The indication of the Clark level (the deepest tumor-infiltrated skin layer) and the mitotic rate are no longer included in this classification.

The N-category of malignant melanoma includes clinically visible or palpable as well as clinically occult, histologically determined lymph node metastases in the lymphatic drainage area of the tumor and their number. Furthermore, in this category extranodal (outside of lymph nodes) located regional metastases (close to the tumor) are taken into account: satellite metastases (clinically conspicuous metastases within a distance of two centimeters from the primary tumor), microsatellites (clinically occult metastases in the immediate vicinity of the primary tumor) and in transit- Metastases (clinically noticeable metastases along the lymph vessels at least two centimeters from the primary tumor, but in front of the sentinel lymph node).

The decisive criteria for determining the M category are which organ or organs are affected by distant metastases and whether there is an increase in the blood level of the tumor marker lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

On the basis of the TNM classification, the tumor stage is determined on which further treatment and follow-up care of the melanoma disease are based.

| T category | Tumor thickness

(to |

Ulceration |

|---|---|---|

|

Tx

|

can not

to be determined |

|

| T0 | no primary tumor 1 | |

| Tis | Melanoma in situ | |

| T1 | ≤1.0 mm | unknown |

| T1a | <0.8 mm | No |

| T1b | Yes | |

| 0.8mm - 1.0mm | Yes No | |

| T2 | > 1.0-2.0 mm | unknown |

| T2a | No | |

| T2b | Yes | |

| T3 | > 2.0-4.0 mm | unknown |

| T3a | No | |

| T3b | Yes | |

| T4 | > 4.0 mm | unknown |

| T4a | No | |

| T4b | Yes | |

| 1 z. B. completely regressive tumor | ||

| N category | Number metastatic

infested regional Lymph nodes |

extranodal

regional Metastases |

|---|---|---|

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes

were not judged |

No |

| N0 | 0 | |

| N1 | 1, or:

extranodal regional metastases without lymph node metastases |

|

| N1a | 1 (occult) | No |

| N1b | 1 (clinical) | |

| N1c | 0 | Yes |

| N2 | 2-3, or:

1 and extranodal regional metastases |

|

| N2a | 2-3 (occult) | No |

| N2b | 2-3 (of which at least one clinical) | |

| N2c | 1 (clinical or occult) | Yes |

| N3 | ≥4, or:

≥2 and extranodal regional metastases, or: lymph node conglomerate 1 without extranodal regional metastases |

|

| N3a | ≥4 (occult) | No |

| N3b | ≥4 (of which at least one is clinical) | |

| N3c | ≥2 (clinical or occult)

and / or lymph node conglomerate * |

Yes |

|

1 Lymph node conglomerate: several lymph nodes that have become caked together due to metastatic involvement |

||

| M category | Anatomical

localization of distant metastases |

LDH value |

|---|---|---|

| M0 | No distant metastases | |

| M1 | To be available

of distant metastases |

|

| M1a | Skin and soft tissues

including muscle and / or lymph nodes distant from the tumor |

unknown |

| M1a (0) | normal | |

| M1a (1) | elevated | |

| M1b | Lung 1 | unknown |

| M1b (0) | normal | |

| M1b (1) | elevated | |

| M1c | other internal organs

without central nervous system 2 |

unknown |

| M1c (0) | normal | |

| M1c (1) | elevated | |

| M1d | central nervous system 3 | unknown |

| M1d (0) | normal | |

| M1d (1) | elevated | |

|

1 with or without M1a, 2 with or without M1a or M1b, 3 with or without M1a, M1b or M1c |

||

| stage | T-

classification |

N-

classification |

M-

classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| T1b | N0 | M0 | |

| IB | T2a | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T2b | N0 | M0 |

| T3a | N0 | M0 | |

| IIB | T3b | N0 | M0 |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | |

| IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 |

| stage | T-

classification |

N-

classification |

M-

classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| IIIA | T1a / b-T2a | N1a or N2a | M0 |

| IIIB | T0 | N1b, N1c | M0 |

| T1a / b-T2a | N1b / c or N2b | M0 | |

| T2b / T3a | N1a-N2b | M0 | |

| IIIC | T0 | N2b, N2c, N3b or N3c | M0 |

| T1a-T3a | N2c or N3a / b / c | M0 | |

| T3b / T4a | Every N ≥N1 | M0 | |

| T4b | N1a-N2c | M0 | |

| IIID | T4b | N3a / b / c | M0 |

| IV | Every T, Tis | Every N | M1 |

Prognosis (consequences and complications)

The stages of the TNM classification , the subtype (for example, LMM has a better prognosis than AMM), tumor location and gender (men have a worse prognosis) provide criteria for prognosis and therapy . The darkness or lightness of the melanoma has no influence on the prognosis. The exception to this is amelanotic melanoma, which has a poorer prognosis.

With early diagnosis and treatment, the chance of a cure is good. In particular in the case of “in situ melanomas”, ie melanomas that have not yet broken through the so-called basement membrane - the boundary between the epidermis (epidermis) and dermis (dermis) - the risk of metastasis is 0%. Most melanomas are already recognizable at this stage.

For thin melanomas (vertical tumor thickness less than 0.75 mm), the chances of recovery are around 95 percent. The five-year survival rate (= proportion of patients who are still alive five years after the disease was diagnosed) depends on the stage at which the cancer has spread:

- Stage I (primary tumor ≤ 2 mm thick or ≤ 1 mm and ulceration or mitosis) 98%

- Stage II (primary tumor> 2 mm thick or> 1 mm and ulceration or mitosis) 82-94%

- Stage III (settlement in the nearest lymph nodes or skin metastases in the area) 92-93%

- Stage IV ( metastases in more distant lymph nodes or other organs) 10-18%

The melanoma can metastasize into different organs; there are no preferred target organs as with other tumors ( e.g. colon carcinoma → liver ). Metastases are common in the liver, skin, lungs , skeleton and brain . Liver and brain metastases in particular have an unfavorable influence on the prognosis, whereas experience has shown that melanoma metastases in the lungs tend to increase slowly in size. The cause of this clinical observation is not yet known. Typically, malignant melanoma also often metastasizes to the heart . Heart metastases from malignant melanoma are among the most common of the otherwise rare malignant heart tumors. About 40–60% of heart metastases have their origin in malignant melanoma.

Only an early and complete removal of a melanoma can lead to healing. Waiting, whether out of negligence or fear, worsens the outlook significantly. That is why preventive examinations and early detection measures are particularly important for people who are particularly at risk.

Forecast of metastatic melanoma

Once a melanoma has formed daughter tumors, there is almost no cure. However, life expectancy is very different. Hauschild and his colleagues found a favorable prognosis in 1365 patients with a BRAF V600 mutated, metastatic melanoma with low LDH , a good general condition and a small total diameter of the melanoma manifestations. BRAF is a tyrosine kinase that often has the typical mutation V600 in melanomas, and in this case treatment with BRAF inhibitors is promising. The above-mentioned risk factors were found earlier, when therapy with BRAF inhibitors was not yet possible. Various studies examining the effects of BRAF inhibitors only included patients with the V600 mutation of the BRAF gene (BRIM-2, BRIM-3, BRIM-7 and the coBrim study). These study patients have now been re-evaluated using a special statistical method, recursive partitioning (RPA). Progression-free survival, i.e. H. Life without tumor progression (= PFS) and overall survival, that is, survival regardless of the cause of death (= OS) are calculated. The general condition was determined according to the ECOG PS . An ECOG 0 was considered to be in good general condition. The most favorable group was those with low LDH, good general health, and a low cumulative score for the longest target lesion diameters. The median progression-free survival was 11.1 months and the overall survival was 27.2 months. With an elevated baseline LDH, progression-free survival was only 3.5 months and the median overall survival was only 6 months. The prognostic factors have not fundamentally changed due to the new therapy options.

treatment

The most important form of therapy is the surgical removal of the primary tumor . The tumor should always be removed as a whole. If a malignant melanoma is suspected, biopsies are not taken in order to avoid spreading into the bloodstream and / or the lymphatic fluid. A sufficient safety distance should be observed when removing. Depending on the tumor thickness, this is 1 or 2 cm; in addition, all layers of skin under the tumor except for the muscle fascia should be removed. In the case of melanomas on the face or on the acres , instead of maintaining a large safety distance , an excision with microscopically controlled surgery can be carried out, in which a complete removal in the healthy is ensured by means of checking the cutting edge under the microscope.

In accordance with the current melanoma guideline, it is generally recommended from a tumor thickness of 1 mm, in individual cases from a tumor thickness of 0.75 mm, to additionally identify the sentinel lymph node and examine it histologically. The sentinel lymph node offers an important prognostic factor (classification in stage II or III). If the sentinel lymph node is affected, general removal of the other lymph nodes at this location is recommended. Removal of the sentinel lymph node does not offer any further therapeutic advantages; nevertheless, the prognostic value is recommended as very important for further therapy and follow-up care of the melanoma. If the melanoma tumor mass in the sentinel lymph node is low, molecular genetic risk factors can provide additional prognostic information.

For melanomas with a greater tumor thickness without further lymph node involvement (stage II) and after removal of the lymph nodes (stage III), adjuvant therapy using interferon alpha for 18 months is recommended. Even if this probably has no measurable impact on overall survival, it is intended to delay the occurrence of tumor recurrence.

In later stages, when the tumor has already metastasized to the skin, lymph nodes, and internal organs , the chance of healing is slim. A whole range of therapy alternatives are used and tested here, which usually only offer temporary improvement, but usually have no prospect of a cure. These include chemotherapy with DTIC or Fotemustin , surgery to reduce tumor mass, or radiation therapy . New therapeutic approaches are based on the blockade of molecular processes in the signal transduction of the cell : The first initially promising studies on a combination of a classic chemotherapeutic agent with tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib did not show sufficient superiority of this therapy.

Medicines from the group of BRAF inhibitors have been successfully tested and are now approved: Vemurafenib received a positive recommendation from the European regulatory authority in 2012, followed by the active ingredient dabrafenib in 2013 . However, therapy with BRAF inhibitors is only possible for melanoma patients with a BRAF V600E / K mutation (approx. 50% of patients) and the effect of the drug is almost always temporary. As a rule, after treatment with b-raf inhibitors, the tumor and its metastases develop resistance after about six months, so that progress occurs again. This one tries with the now also approved MEK inhibitors trametinib or Cobimetinib delay. The combination of the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib and the MEK inhibitor binimetinib represents a significant advance, also in the treatment of inoperable metastatic melanomas . In biochemical studies, encorafenib has a long retention time ( dissociation half- life ) of more than 30 hours on the mutated BRAFV600E- Protein on - as opposed to 2 hours for dabrafenib and 0.5 hours for vemurafenib. Binimetinib together with encorafenib increases the effectiveness compared to the BRAF inhibitor monotherapy if it is adequately tolerated.

Another therapeutic option is aimed at stimulating the immune system ( cancer immunotherapy ). The monoclonal antibody ipilimumab has been approved for this purpose in the EU since 2011 . The monoclonal antibody nivolumab acts in a similar way (as an immune checkpoint inhibitor ) against the checkpoint receptor PD-1 (i.e. a PD-1 inhibitor), which has achieved promising results in initial clinical studies. Nivolumab ( Opdivo ) was approved in the EU in June 2015. In October 2015, the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care identified an added benefit in a dossier assessment for previously untreated patients whose tumor V600 mutation is negative. After previous FDA approval in the USA, which took place in 2014, another PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab ( Keytruda ) was approved in the EU in July 2015 as a monotherapy for the treatment of advanced, i.e. H. unresectable or metastatic malignant melanoma approved in adults. The immune checkpoint inhibitors proved to be effective for the palliative and adjuvant treatment of melanoma. In melanomas with low or no PD-L1 expression, combination therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab is more effective than anti-PD1 monotherapy, but it also causes severe immunological side effects more frequently.

In addition, various cellular, immunotherapeutic methods are currently being tested in preclinical trials or clinical studies on the basis of malignant melanoma . Among other things, the therapeutic potential of melanoma-specific T cells or antigen-loaded dendritic cells is tested. It should be emphasized that, in contrast to leukemias , which are also tested for various cellular immunotherapies, melanoma is a solid, compact tumor that is less easily accessible to immune cells.

Regular follow-up examinations are recommended for patients who have previously had malignant melanoma.

Late metastases and CUP ( C ancer of U Nknown P rimary, unknown primary cancer) are common in malignant melanoma.

To follow-up includes not only regular check-ups to relapse to recognize in good time, but if necessary psycho-oncology consultations, to facilitate the rehabilitation of patients. The Cancer League recommends that those affected slowly return to everyday life and an individual coping strategy that is based on their own wishes and needs and includes outside help.

literature

- Giuseppe Palmieri, Mariaelena Capone, Maria Libera Ascierto, Giusy Gentilcore, David F. Stroncek, Milena Casula, Maria Cristina Sini, Marco Palla, Nicola Mozzillo, Paolo A. Ascierto: Main roads to melanoma . In: Journal of Translational Medicine . tape 7 , 2009, ISSN 1479-5876 , p. 86 , doi : 10.1186 / 1479-5876-7-86 , PMID 19828018 , PMC 2770476 (free full text).

- YM Chang et al. a .: Sun exposure and melanoma risk at different latitudes: a pooled analysis of 5700 cases and 7216 controls. In: International journal of epidemiology. Volume 38, Number 3, June 2009, pp. 814-830. doi: 10.1093 / ije / dyp166 . PMID 19359257 . PMC 2689397 (free full text).

- Claus Garbe: Management of Melanoma. Verlag Springer, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-540-28987-9 limited preview in the Google book search

- C. Garbe et al. a .: Therapy of melanoma. In: Dtsch Arztebl 105, 2008, pp. 845–851. doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2008.0845

- JK Rivers: Is there more than one road to melanoma? In: The Lancet . Volume 363, Number 9410, February 2004, pp. 728-730. doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (04) 15649-3 . PMID 15005091 . (Review).

- C. Garbe, D. Schadendorf: Malignant melanoma - new data and concepts for aftercare. In: Dtsch Arztebl. 100, 2003, pp. A-1804 / B-1501 / C-1409

- J. Bertz: Epidemiology of the malignant melanoma of the skin. In: Bundesgesundheitsblatt 44, 2001, pp. 484-490. ISSN 1436-9990 .

- S3 guideline for diagnosis, therapy and aftercare of melanoma of the German Cancer Society (DKG) and the German Dermatological Society (DDG). In: AWMF online (as of 2013)

- Claus Garbe (Hrsg.): Melanom: updated therapy recommendation of the S3 guideline for diagnosis, therapy and aftercare of melanoma . Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2016, DNB 1117827666

- PE LeBoit, G. Burg, D. Weedon, A. Sarasain: Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours . In: World Health Organization (Ed.): WHO Classification of Tumors . 3rd ed. Volume 6 . WHO Press, Geneve 2005, ISBN 978-92-832-2414-3 .

Web links

- PathoPic - Image database of the University of Basel: Histological images of malignant melanomas

- PathoPic - image database of the University of Basel: Macroscopic images of malignant melanomas and their metastases

- PathoPic - Image database of the University of Basel: Cytological images of malignant melanomas and their metastases

- Spread of malignant melanoma

- Melanoma Molecular Map Project (English)

- hautkrebs.de - the skin cancer information portal

- Information about melanoma. University Hospital Bonn

- Page of the Dermatological Information System on Malignant Melanoma

- Melanoma on Oncotrends.de, developments and trends in oncology

- Monika Preuk: Medical rarities: Spectacular insights into the body ; to 3: Liver with melanoma metastases ; Image from the Medical History Museum Berlin

- List of certified skin tumor centers in Germany ; 58 certified skin tumor centers in Germany (as of March 26, 2019)

- Malignant Melanoma on ONKODIN: Oncology, Hematology - Data and Information , Information Page for Healthcare Professionals

- Malignant melanoma on krebs.de , information page for patients

Individual evidence

- ↑ BM Helmke, HF Otto: The anorectal melanoma . (Anorectal melanoma. A rare and highly malignant tumor entity of the anal canal). In: The Pathologist . tape 25 , no. 3 , May 2004, pp. 171-177 , doi : 10.1007 / s00292-003-0640-y , PMID 15138698 (review).

- ↑ EC Jehle u. a .: colon carcinoma, rectal carcinoma, anal carcinoma. (PDF; 1.13 MB) August 2003, ISSN 1438-8979 , p. 1.

- ↑ a b c M. Volkenandt: Malignant melanoma. In: O. Braun-Falco u. a. (Ed.): Dermatology and Venereology. Verlag Springer, 2005, ISBN 3-540-40525-9 , pp. 1313-1324 limited preview in Google book search

- ^ Cancer in Germany 2009/2010. (PDF) Robert Koch Institute , 9th edition, 2013, p. 60 ff .; Retrieved May 19, 2014

- ↑ The 20 most common causes of cancer death in Germany in 2007 . ( Memento of the original from January 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Krebsatlas , German Cancer Research Center, May 6, 2009, accessed on March 27, 2010.

- ↑ a b melanoma. ( Memento of the original from May 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 143 kB) Medicines for People, European Association of the Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (Ed.)

- ↑ S. Rötzer: Quality of life in melanoma patients under adjuvant interferon alpha 2a therapy. Dissertation, Charité Berlin, 2008.

- ↑ Renee A. Desmond, Seng-jaw Soong: Epidemiology of malignant melanoma . In: The Surgical Clinics of North America . tape 83 , no. 1 , February 2003, p. 1-29 , PMID 12691448 .

- ↑ Climate . In: Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand .

- ↑ H. Hamm, PH Höger: Skin tumors in childhood. In: Dt. Medical journal. 108, 20, 2011.

- ↑ U. Beise: Melanoma: Sunlight isn't the only cause. In: Ars Medici 15/2004, pp. 775f.

- ↑ Malignant melanoma ("black skin cancer") . ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) In: Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft , July 7, 2008, accessed on October 14, 2008.

- ↑ Melanoma / Melanoma (ICD 172) . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Cancer Atlas . German Cancer Research Center, accessed on October 14, 2008.

- ↑ D. Hill: Efficacy of sunscreens in protection against skin cancer . In: Lancet . tape 354 , no. 9180 , August 28, 1999, p. 699-700 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (99) 00192-0 , PMID 10475178 . or Ken Landow: Do sunscreens prevent skin cancer? In: Postgraduate Medicine . tape 116 , no. 1 , July 2004, p. 6 , PMID 15274282 .

- ^ Marianne Berwick: Counterpoint: sunscreen use is a safe and effective approach to skin cancer prevention . In: Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology . tape 16 , no. 10 , October 2007, p. 1923-1924 , doi : 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-07-0391 , PMID 17932338 . or Adèle C. Green, Gail M. Williams: Point: sunscreen use is a safe and effective approach to skin cancer prevention . In: Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention . tape 16 , no. 10 , October 2007, p. 1921-1922 , doi : 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-07-0477 , PMID 17932337 .

- ↑ P. Wolf: Sunscreens . (Sunscreens. Protection against skin cancers and photoaging). In: The dermatologist; Journal Of Dermatology, Venereology, And Related Fields . tape 54 , no. 9 , September 2003, p. 839-844 , doi : 10.1007 / s00105-003-0590-6 , PMID 12955261 .

- ^ Leslie K. Dennis, Laura E. Beane Freeman, Marta J. VanBeek: Sunscreen use and the risk for melanoma: a quantitative review . In: Annals of Internal Medicine . tape 139 , no. 12 , December 16, 2003, p. 966-978 , PMID 14678916 ( annals.org [PDF]).

- ↑ Nature , quoted from: How UV radiation promotes black skin cancer. In: Mitteldeutsche Zeitung. June 14, 2014, accessed June 12, 2014 .

- ↑ amboss.miamed.de

- ↑ R. Dummer u. a .: Melanocytic nevi and cutaneous melanoma. (PDF direct access at DocPlayer.org) In: Swiss Medical Forum , 10, 2002, pp. 224–231.

- ^ A b c d e R. Dobrowolski: In-vitro and in-situ analysis of the tumor suppressor gene hp19 ARF in malignant melanomas . Dissertation, RWTH Aachen 2004, p. 8 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Kumar, Vinay, 1944-, Abbas, Abul K., Aster, Jon C., Perkins, James A .: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease . 9th edition. Philadelphia, PA 2015, ISBN 978-1-4557-2613-4 , pp. 1147-1149 .

- ↑ Guideline for early cancer detection (Banz. No. 37, p. 871) of March 6, 2008 (PDF)

- ↑ J. Malvehy, A. Hauschild, C. Curiel-Lewandrowski, P. Mohr, R. Hofmann-Wellenhof, R. Motley, C. Berking, D. Grossman, J. Paoli, C. Loquai, J. Olah, U Reinhold, H. Wenger, T. Dirschka, S. Davis, C. Henderson, H. Rabinovitz, J. Welzel, D. Schadendorf, U. Birgersson: Clinical performance of the Nevisense system in cutaneous melanoma detection: an international, multicentre , prospective and blinded clinical trial on efficacy and safety . In: British Journal of Dermatology . tape 171 , no. 5 , November 2014, ISSN 1365-2133 , p. 1099-1107 , doi : 10.1111 / bjd.13121 , PMID 24841846 .

- ^ P. Mohr, U. Birgersson u. a .: Electrical impedance spectroscopy as a potential adjunct diagnostic tool for cutaneous melanoma . In: Skin Research and Technology . May 2013, Volume 19, Number 2, pp. 75-83, doi: 10.1111 / srt.12008

- ↑ David Globig: On the trail of black skin cancer. New laser light method improves early diagnosis . Deutschlandfunk , June 20, 2007, accessed October 14, 2008.

- ↑ Dieter Leupold: The stepwise two-photon excited melanin fluorescence is a unique diagnostic tool for the detection of malignant transformation in melanocytes . In: Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research , May 2, 2011, doi: 10.1111 / j.1755-148X.2011.00853.x .

- ↑ Matthias Scholz u. a .: En route to a new in vivo diagnostic of malignant pigmented melanoma . In: Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research , January 23, 2012, doi: 10.1111 / j.1755-148X.2012.00966.x

- ↑ Maria Rita Gaiser, Nikolas von Bubnoff, Christoffer Gebhardt, Jochen Sven Utikal: Liquid Biopsy for the monitoring of melanoma patients. In: JDDG: Journal of the German Dermatological Society. 16, 2018, p. 405, doi : 10.1111 / ddg.13461_g .

- ↑ C. Garbe u. a .: German guideline: Malignant melanoma. Downloads (PDF) on the AWMF website, accessed on January 29, 2018

- ↑ R. Hein: The acrolentiginous melanoma. (PDF; 312 kB) In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt 98, 2001, A-111 – A-115.

- ↑ C. Garbe: Management of Melanoma. Verlag Springer, 2006, ISBN 3-540-28987-9 limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care of melanoma, long version 3.2. AWMF registration number: 032 / 024OL. In: AWMF online. Oncology Guideline Program (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Diagnostik, 2019, p. 43 , accessed on April 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 58 .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 58 f .

- ↑ a b Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 59 .

- ↑ Eduardo Calonje, Thomas Brenn, Alexander Lazar, Steven D. Billings: McKee's pathology of the skin with clinical correlations . Fifth ed.Elsevier, no place, ISBN 978-0-7020-7552-0 , p. 1314 .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 58, 60 .

- ^ Markus Hantschke, Boris C. Bastian, Philip E. LeBoit: Consumption of the epidermis: a diagnostic criterion for the differential diagnosis of melanoma and Spitz nevus . In: The American Journal of Surgical Pathology . tape 28 , no. December 12 , 2004, ISSN 0147-5185 , p. 1621-1625 , doi : 10.1097 / 00000478-200412000-00011 , PMID 15577682 .

- ↑ Eduardo Calonje, Thomas Brenn, Alexander Lazar, Steven D. Billings: McKee's pathology of the skin with clinical correlations . Fifth ed.Elsevier, no place, ISBN 978-0-7020-7552-0 , p. 1313 .

- ↑ a b Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 60 f .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 67 .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 60 .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 71 .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 66 ff .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 68 f .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 73 ff .

- ↑ Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors . 2005, p. 50 .

- ^ Oncology guideline program (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF): Diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care of melanoma . In: AWMF online . Register number: 032 / 024OL, 2019, p. 186 f . ( leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de [accessed on May 23, 2020]).

- ↑ Gershenwald Je, Scolyer Ra, Hess Kr, Sondak Vk, Long Gv: Melanoma Staging: Evidence-based Changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. 2017, accessed on May 23, 2020 .

- ^ Oncology guideline program (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF): Diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care of melanoma . In: AWMF online . Register number: 032 / 024OL, 2019, p. 30th ff . ( leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de [accessed on May 23, 2020] section "Classification" and tables on TNM classification and staging).

- ↑ Gershenwald Je, Scolyer Ra, Hess Kr, Sondak Vk, Long Gv: Melanoma Staging: Evidence-based Changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. 2017, accessed on May 23, 2020 (English, figures stage I-III).

- ↑ JE Gershenwald, DL Morton, JF Thompson, JM Kirkwood, S. Soong: Staging and prognostic factors for stage IV melanoma: Initial results of an American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) international evidence-based assessment of 4,895 melanoma patients . In: Journal of Clinical Oncology . tape 26 , 15_suppl, May 20, 2008, ISSN 0732-183X , p. 9035–9035 , doi : 10.1200 / jco.2008.26.15_suppl.9035 ( ascopubs.org [accessed May 23, 2020] Abstract presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2008 Annual Meeting).

- ↑ C. Kisselbach et al. a .: women and cardiac neoplastic manifestations on the heart and pericardium. In: Herz 30/2005, pp. 409-415.

- ↑ H. Roskamm: heart disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, therapy. Springer, 2004, ISBN 3-540-40149-0 , p. 1339.

- ^ A Hauschild, J Larkin, A Ribas, B Dréno, KT Flaherty, PA Ascierto, KD Lewis, E McKenna, Q Zhu, Y Mun, GA McArthur: Modeled Prognostic Subgroups for Survival and Treatment Outcomes in BRAF V600-Mutated Metastatic Melanoma: Pooled Analysis of 4 Randomized Clinical Trials. in JAMA Oncol. 2018; Volume 4 (Issue 10): pp. 1382-1388. PMID 30073321 . PMC 6233771 (free full text) doi: 10.1001 / jamaoncol.2018.2668 .

- ^ Leon van Kempen: Molecular pathology of cutaneous melanoma . In: Melanoma Management . tape 1 (2) , 2014, pp. 151-164 .

- ^ Georg Brunner: A nine-gene signature predicting outcome in cutaneous melanoma . In: Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology . tape 139 (2) , 2013, pp. 249-258 .

- ↑ Francesco Spagnolo, Paola Ghiorzo, Laura Orgiano, Lorenza Pastorino, Virginia Picasso, Elena Tornari, Vincenzo Ottaviano, Paola Queirolo: BRAF-mutant melanoma: treatment approaches, resistance mechanisms, and diagnostic strategies. In: OncoTargets and Therapy , pp. 157-168, doi: 10.2147 / OTT.S39096 .

- ↑ Gerald Falchook, Radhika Kainthla, Kevin Kim: Dabrafenib for treatment of BRAF-mutant melanoma. In: Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine. P. 21, doi: 10.2147 / PGPM.S37220 .

- ↑ technical information Braftovi , accessed on 21 October 2018

- ↑ JP Delord et al .: Phase I Dose-Escalation and -Expansion Study of the BRAF Inhibitor Encorafenib (LGX818) in Metastatic BRAF-Mutant Melanoma . In: Clinical Cancer Research . tape 23 , no. 19 , September 2017, p. 5339-5348 , doi : 10.1158 / 1078-0432.CCR-16-2923 , PMID 28611198 .

- ↑ technical information Mektovi , accessed on 21 October 2018

- ↑ R Dummer et al .: Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomized phase 3 trial . In: The Lancet Oncology . tape 19 , no. 5 , May 2018, p. 603-615 , doi : 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (18) 30142-6 , PMID 29573941 .

- ↑ R Dummer et al .: Overall survival in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma receiving encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial. In: The Lancet Oncology . tape 19 , no. 10 , October 2018, p. 1315-1327 , doi : 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (18) 30497-2 , PMID 30219628 .

- ↑ P Koelblinger et al .: Development of encorafenib for BRAF-mutated advanced melanoma . In: Current Opinion in Oncology . tape 30 , no. 2 , March 2018, p. 125-133 , doi : 10.1097 / CCO.0000000000000426 , PMID 29356698 , PMC 5815646 (free full text).

- ↑ Benjamin Scheiermann, Rodabe Amaria, Karl Lewis, Rene Gonzalez: Novel therapies in melanoma . In: Immunotherapy . tape 3 , no. December 12 , 2011, p. 1461-1469 , doi : 10.2217 / imt.11.136 , PMID 22091682 (review).

- ↑ Christoph Baumgärtel: Melanoma - New Therapy Options. (PDF; 20.5 MB) February 27, 2012, pp. 42–44 , accessed on February 27, 2012 .

- ↑ Patrick Terheyden, Angela Krackhardt, Thomas Eigenler: System therapy of melanoma. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and inhibition of intracellular signal transduction. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 116, Issue 29 f., (July 22) 2019, pp. 497–504.

- ↑ SL Topalian, M. Sznol et al. a .: Survival, Durable Tumor Remission, and Long-Term Safety in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Receiving Nivolumab. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. 32, 2014, p. 1020, doi: 10.1200 / JCO.2013.53.0105 .

- ^ C. Robert, GV Long et al. a .: Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. In: The New England Journal of Medicine , Volume 372, Number 4, January 2015, pp. 320-330, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1412082 , PMID 25399552 .

- ↑ Melanoma therapy: first PD-1 inhibitor approved . In: Pharmazeutische Zeitung , June 29, 2015; accessed on July 28, 2015

- ↑ Yuri Sankawa: Nivolumab approved as monotherapy for advanced malignant melanoma. In: Journal Onko. , Volume 6, dated July 31, 2015

- ↑ [A15-27] Nivolumab - benefit assessment according to Section 35a SGB V (dossier assessment). In: iqwig.de. Retrieved October 27, 2015 .

- ↑ Immunotherapy approved for skin cancer . In: Pharmazeutische Zeitung , July 22, 2015; accessed on July 28, 2015

- ↑ Patrick Terheyden, Angela Krackhardt, Thomas Eigenler: System therapy of melanoma. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and inhibition of intracellular signal transduction. 2019.

- ↑ SA Rosenberg, JC Yang u. a .: Durable Complete Responses in Heavily Pretreated Patients with Metastatic Melanoma Using T-Cell Transfer Immunotherapy. In: Clinical Cancer Research. 17, 2011, p. 4550, doi: 10.1158 / 1078-0432.CCR-11-0116 .

- ↑ Sandra Höfflin, Sabrina Prommersberger u. a .: Generation of CD8 T cells expressing two additional T-cell receptors (TETARs) for personalized melanoma therapy. In: Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2015, p. 00, doi: 10.1080 / 15384047.2015.1070981 .

- ↑ Sébastien Anguille, Evelien L Smits et al. a .: Clinical use of dendritic cells for cancer therapy. In: The Lancet Oncology. 15, 2014, p. E257, doi: 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (13) 70585-0 .

- ↑ Jens Dannull, N. Rebecca Haley et al. a .: Melanoma immunotherapy using mature DCs expressing the constitutive proteasome. In: Journal of Clinical Investigation. 123, 2013, p. 3135, doi: 10.1172 / JCI67544 .

- ↑ EHJG Aarntzen, G. Schreibelt u. a .: Vaccination with mRNA-Electroporated Dendritic Cells Induces Robust Tumor Antigen-Specific CD4 + and CD8 + T Cells Responses in Stage III and IV Melanoma Patients. In: Clinical Cancer Research. 18, 2012, p. 5460, doi: 10.1158 / 1078-0432.CCR-11-3368 .

- ↑ Swiss Cancer League (Ed.): Melanom. Black skin cancer . Bern July 2017, p. 39 ( online [PDF; accessed February 3, 2018]).