Minorities in France

This article deals with population groups traditionally living in France (French minorités nationales ) - the so-called "old minorities" - who are perceived by the French majority society as ethnic or linguistic minorities. On the other hand, migrants from Europe and from the non-European colonies of France, as they did not immigrate until after the Second World War (“new minorities”, see for example: Koreans in France ) are not treated .

Traditional minorities

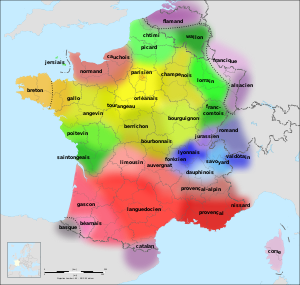

The minorities in France are:

- Basques in the Basque Country

- Bretons in Brittany

- Germans in Alsace and parts of Lorraine ( German-Lorraine )

- Flemings around Dunkirk ( French Flanders ) and in the northeast of Artois

- Catalans in Roussillon

- Italians in Alpes-Maritimes

- Corsicans in Corsica

- Occitan in the southern third of France.

- The Gens du Voyage (literally: " traveling people ", a term that in France encompasses Roma , Yeniches , Manouches and Forains ) live all over France .

The proportion of the population of these groups (excluding the Gens du Voyage ) is put at 8.133 million at 13.9%, of which the Occitans make up about 2 million.

In exceptional cases (Corsica) there are special protective rights due to autonomy regulations. The rule, however, is not to allow any exception from the entire French "state people". France - alongside Turkey and Greece - has neither put into force nor ratified the framework agreement of the Council of Europe from 1995 for the protection of national minorities, "the most important point of reference in the European minority protection system".

In 1539, King Francis I's edict of Villers-Cotterêts stipulated that French (the dialect of Île-de-France ) would be spoken in France . In 1790, Paris declared French the only language of the republic, freedom and reason and the regional languages to be dialects ( patois ).

Regional languages have been recognized and taught to a limited extent in schools since the 1970s / 80s and the decentralization laws of 1982 . This was not least due to the strengthening of the regional autonomy and independence movements. In Corsica , the FLNC even took up arms and carried out several terrorist attacks. Corsica is the only department to date that has a special regional status. Improvements in the area of cultural autonomy and ongoing decentralization have so far only marginally supported the survival and revitalization of these minority languages. Some of these languages remain threatened with extinction.

Basques

In the French Basque Country around 100,000–200,000 Basques live in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department . However, only a fraction of them speak the Basque language .

The Basque people are separated by the border between France and Spain , but the people of the Basque Country still consider them to be one ethnic group. The majority of the Basque population lives on Spanish territory (around 1,000,000). But here, too, only about a quarter speak their vernacular.

The Spanish Basque Country has been an autonomous community in Spain since 1979 . The autonomy of this region is based not only on the cultural and political area, but also on the financial one. As a result, the Autonomous Community collects the taxes on its own territory and only pays a sum to the Spanish central government, which is determined by a bilateral agreement. Despite the good statute of autonomy in Spain (especially compared to the French Basques) there is an active independence movement in the Basque Country there. The best known is the terrorist organization ETA , which also call for the unification of the North and South Basques.

In France there is even no department that is entirely Basque. The three historic Basque provinces ( Labourd , Basse-Navarre and Soule ) are together with Béarn and a small piece of Gascon in the Pyrénées-Atlantique department.

Bretons

The present-day Bretons in Brittany are partly the descendants of a Celtic people. These island celts came from Great Britain in the 5th century and brought their language to the region.

The main distribution area of the Breton language are the Finistère department ( Penn ar Bed "Cape of the World") and the western part of the departments Côtes-d'Armor ( Aodoù-an-Arvor "coasts of the sea") and Morbihan ( Mor-bihan "small Sea"). Part of the historic province of Brittany had been bilingual from the start, ie roughly the eastern part of Côte-d'Armor and the south-western part of the Ille-et-Vilaine department . Only Gallo and French have been used there since the Middle Ages . The two traditional provincial capitals ( Rennes and Nantes ) are both located in an area where Breton was never spoken, but Gallo. Since the Middle Ages, the language border between Gallo- or French-speaking Brittany ( Haute-Bretagne ) and Bretagne bretonnante or Haute-Bretagne has shifted further and further west.

According to a study, around 172,000 of the 2.3 million Bretons still spoke Breton in 2007. 2/3 of them were older than 60 years and only 5% younger than 15. The sharp decline in the Breton language can also be seen in the fact that around 90% of western Brittany spoke the language before the First World War and after the Second World War About 1.2 million (75%) of the Breton language were proficient, in 2007 it was still 22%.

From the end of the 19th century, a regionalist movement (Breton emsav or emzao ) formed in Brittany , organizations such as the Union Régionaliste Bretonne (1898) and Fédération Régionaliste de Bretagne (1918) stood up for the preservation of the Breton language and cultural traditions of the region. This movement came to a standstill due to the First World War, in which a relatively large number of Bretons perished - this is also attributed to the fact that Breton-speaking soldiers did not understand the instructions of their officers, were despised by them and in some cases were deliberately used as "cannon fodder". In occupied France during World War II, a Breton minority collaborated with the Germans, because they hoped for more cultural freedom and independence. This collaboration became the undoing of many nationalists and provided the Paris central government with sufficient excuses to make an example. In the post-war period, the Breton language was banned from the public and its number of speakers decreased drastically. In the 1950s and 60s, the reputation of their own language in the eyes of many Bretons reached an all-time low: As in other regions, in addition to external pressure, increasing geographical and social mobility in Brittany, which was previously poor and rural, led to the fact that French became the dominant language. At the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, the cultural and political demands of the Bretons experienced a renaissance, favored by the development of a diverse Breton music scene.

Today there are state and private schools with bilingual schools (12,782 students at the beginning of the 2016/17 school year) and the private écoles Diwan with exclusively Breton as the language of instruction (4242 students at the beginning of the 2016/17 school year). The number of students in Breton or bilingual classes has almost doubled within 10 years. These 17,000 students are compared to 350,000 students in purely French-speaking schools. The majority of parents now raise their children in French; in 2007, 35–40% of Breton-speaking parents said they would pass the language on to their children.

German

Alsatian and Lorraine are spoken in the Bas-Rhin , Haut-Rhin and Moselle departments . Apart from the regions around Orbey , Montreux and Courtavon-Levoncourt, the whole of Alsace is traditionally German-speaking. The Alsatian dialects are Alemannic (except for a small part in the north, which is assigned to Franconian) and do not differ much from the dialects on the German side along the border between Germany and France, but Alsatian is influenced by French.

Of the 1.7 million inhabitants of Alsace, 600,000 people spoke Alsatian, according to the Office pour la Langue et Culture d'Alsace (OLCA). A study from 2001 showed that 61% of Alsatians still speak the dialect (in 1945 it was over 90%). Urban, rural and age differences were found:

- over 60: 86%

- 50-60: 77%

- 40-50: 70%

- 30-40: 60%

- 20-30: 38%

- 10-20: 25%

- under 10: 5–10%

After the Second World War, the use of the German language in Alsace and Lorraine experienced a sharp decline. The German minority in France is the only German-speaking minority in Europe that does not have native German tuition. For many decades, German was only taught as an optional foreign language in Alsace and Lorraine, and the German language was missing in the local media and local administration. As a result, the younger generations increasingly refrained from using the German language. Even today, German is only taught as a foreign language in most schools in these regions, but there are now also bilingual schools, so-called ABCM schools. For some years now there have also been some bilingual street signs, with the Alsatian dialect being preferred to High German.

Franconian dialects ( Lorraine : Luxemburgish , Moselle Franconian , Rhine Franconian ) are spoken very rarely in the east and north of the Moselle department. The last census from 1962 showed that 300,000 Lorraine residents speak a Franconian dialect. In the rest of Lorraine, French Lorraine is spoken, although it has largely been supplanted by standard French.

Flemings

The Dutch- speaking inhabitants of Flanders , most of which belong to Belgium , are called Flemings . French Flanders (also known as Southern Flanders) was part of the old county of Flanders and has been French territory ( North Department ) since 1713 . The capital of the Flemings in France is Dunkerque (German Dunkirk , Flemish Duunkerke ).

The language border with French or the Picardy dialect has retreated significantly in a north-easterly direction since the Middle Ages. It was then that she approached Le Touquet .

Today there are still 130,000 residents of the region who speak the West Flemish dialect of Flemish or Dutch. Here, too, the continued existence of the language is threatened. For some years now there have been primary schools here that teach Dutch as a first foreign language.

Catalans

Around 200,000-300,000 Catalans live on French soil . They populate the Pyrénées-Orientales department (which has also been officially called Northern Catalonia in Catalan since 2007 ) and the historic Roussillon landscape .

In 1659, Roussillon came to France through the Peace of the Pyrenees .

The Catalan language has been largely replaced by French today. French is the only official language here. However, Catalan is taught as an optional subject in schools and universities and is still cultivated in part through private initiatives.

Corsicans

The Corsicans live on the Mediterranean island of Corsica .

The Corsican language is a Romance language of the Italian-Romance group and has similarities with the Sardinian language in Sardinia and the Tuscan dialect of Italian . There are around 100,000 speakers who speak it at least as a second language.

In the 20th century there was steady immigration of mainland French people, and after the Algerian War, many displaced pieds-noirs from the former colonies in Corsica were settled. Today this group makes up about half of the population.

Compared to other minorities in France, the will for independence is more pronounced in Corsica. This is how the underground organization Frontu di Liberazione Naziunalista Corsu ( FLNC ) came into being, which tries to force the French government to recognize Corsican independence with bombings and murders . In recent years, the government has granted more and more autonomy in return for an end to the violence. The island has a special status compared to other regions of France.

Nevertheless, in a survey in July 2003, almost 51% of Corsicans voted against the Matignon trial , which was supposed to give Corsica even more autonomy. Although the referendum was not politically binding, the French government respected the vote and stopped any further implementation of the project. The reasons for the failure are seen primarily in the accusation against Lionel Jospin that he legitimized the violence exercised by parts of it through negotiations with representatives of the independence movement. In the years that followed, autonomist and nationalist parties gained significant support. Since the regional elections in November 2015 , they have had a majority in the regional parliament, the Assemblée de Corse , and form the island's government.

Occitan

Occitania is called the southern third of France and includes the landscapes of Provence , Drôme - Vivarais , Auvergne , Limousin , Guyenne , Gascogne and Languedoc . In addition, the Occitan language is spoken in peripheral areas of Italy and within Catalonia ( Val d'Aran ). In Val d'Aran, the language is even an official language, despite the small number of speakers.

About 12 million people live in present-day Occitania, although it is estimated that only 1–3 million of them still speak the Occitan language. Occitan (the name is derived from the Occitan word òc for 'ja', in contrast to the old French oïl 'ja') is, like French, a Gallo-Roman language. The main difference between the two languages is that the Gallo-Roman culture was more pronounced in the south than in the north, and the north was later more strongly influenced by the Frankish culture.

With the annihilation of the Cathars (a religious movement from the 11th to 14th centuries), Occitan culture slowly began to disappear. The emigration of the Waldensians in the 18th century also contributed to this. With the centralization policy of Louis XIV , the Occitan language was also abolished as the language of instruction in public schools and its use in everyday life was pushed back. With the French Revolution , the language finally lost all meaning.

Today the Occitan culture is gaining in importance again, mainly for tourist reasons. Occitan is taught parallel to French in some schools, the Calandretas , and it is now also possible to choose Occitan as a high school diploma. In addition, some of the street signs are again bilingual.

Gens du voyage

Under the generic term gens du voyage (“driving people”, “travelers”), which has been established since the 1970s , originally a term for commercial showmen and circus people as opposed to nomades wandering from the point of view of the authorities without a job or outpatient trade , in the French Official language summarizes several population groups of different ethnic origins and social lifestyles, which from an administrative point of view fulfill the characteristic of a past or current driving way of life or economy:

-

Tsiganes ( Roma groups):

- Manouches (including Sinte , Sinti ) who immigrated to France Roma from the group of the late Middle Ages in the German-speaking and Dutch-Flemish space-based Sinti

- Gitans , Kalé from the Iberian Peninsula and from the south of France, still largely concentrated in the south of France today

- R (r) oms , Eastern and Central Europe, coming especially from Bulgaria and Romania Roma, immigrated in the 19th century to France and there especially by groups of Kalderash , Curara and Lovara represented

- Yéniches (also Jenis , Jenischs , from Rotwelsch “Jenische”, also called Barengre after the distancing term bareskro for “Jenischer” used by Manouches ), understood as an autochthonous group that did not belong to the Roma and had immigrated from German-speaking countries over several generations Or even from the Thirty Years' War to the time of the Second World War, no longer a fixed way of life, historically immigrated especially from Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse as well as Alsace and north-eastern Lorraine, today mostly settled in Alsace-Lorraine, Auvergne and Savoy.

- Socially outclassed other and the nature of the gens du voyage living people without ethnicity to one of these groups or with multiple membership, with a distancing expression from the language of the Roma or Manouche ( pirdo , "traveler, non-Rom") also Pardes called

There are no recent surveys of the number of these gens du voyage and their subgroups. Instead, official announcements are based on figures that were determined in 1960 and 1961 through nationwide censuses of official permits for travelers, which were subsequently updated and extrapolated to the number of actual members. According to the result, first presented to the Prime Minister in 1990 by Arsène Delamoin, the responsible officer in the Secrétariat général à l'intégration , and published with additions in 1992, around 250,000 travelers were to be assumed in 1992, distributed as follows:

- approx. 70,000 year-round travelers

- approx. 70,000 semi-sedentary people who only traveled part of the year and were otherwise settled in a permanent place

- approx. 110,000 sedentary people who had permanently given up the driving way of life

Official publications and parliamentary documents from the relevant legislative and implementation projects do not specifically quantify how large the proportion of ethnic subgroups in the total number of gens du voyage and in the categories of "year-round travelers", "semi-settlers" and "sedentary people" is based on the figures collected “However, they emphasize that most of them, with the exception of the more recent immigrants to Rome , hold French citizenship and occasionally point out that the three Roma groups ( Tsiganes ), of which the Manouches as the largest Subgroups are considered to be the most important and largest group of the gens du voyage as a whole . In particular, the number of Rroms in France was estimated by Louis Schweitzer , President of the Haute Autorité de lutte contre les discriminations et pour l'égalité , at around 10,000. In the literature on the Yéniches , on the other hand, their share has been assessed as the largest numerically and their number is given as 100,000 without specifying sources or bases for calculation.

After "nomadization" was declared legally tolerated for the first time in 1966 and in 1983 the Council of State prohibited the administrations from issuing permanent and unrestricted residence bans against "nomads" in their administrative districts, the French departments and municipalities have been subject to regulations that have been amended several times since 1986 and laws initially stopped and then finally obliged to set up suitable areas for the permanent accommodation of gens du voyage ( aires permanentes d'acceuil ) and for the temporary stay of larger groups ( aires de grand passage ), which is then again when the requirements are met the approval of residence bans outside such areas. According to the status of the most recent survey, at the end of 2009 there were a total of 840 (of the planned 1,867) areas with 19,336 (of the planned 41,596) single spaces for permanent residence and 91 Aires de grand passage . Despite such measures, partly also as a result of the isolation associated with the establishment and location of such areas, the gens du voyage in France are still subject to restrictions on their right of residence, which, in conjunction with the societal discrimination that is widespread in Europe, leads to their disadvantage in the Exercise their civil rights and contribute to access to state social and welfare services.

Among the group-specific languages of the various subgroups, only the Romani dialects play a special role in France , such as those of the Manouches and the Vlach Roma, as well as mixed or Para-Romani languages such as the Caló der Kalé based on French, Catalan or Spanish . Yeniche, on the other hand, are not perceived as a separate linguistic group, but as Germans, Alsatians or - like many Manouches - as French-speaking native speakers. Their traditional German-based internal group language, the Yenish , is said to have largely fallen out of use among the Yenish of the younger generation living in France today.

Individual evidence

- ↑ This is the distinction that is common today in minority law, in minority and migration research, see e.g. B. Maximilian Opitz, The minority policy of the European Union. Problems, potentials, perspectives, Münster 2007, passim.

- ^ Maximilian Opitz, The Minority Policy of the European Union. Problems, Potentials, Perspectives, Münster 2007, p. 309.

- ↑ Maximilian Opitz : The minority policy of the European Union: Problems, Potentials, Perspektiven , Münster 2007, p. 86.

- ↑ http://www.langue-bretonne.com/sondages/NouveauSondageChiffres.html

- ↑ Celine Bergeon: Initiatives et stratégies spatiales: le projet circulatoire face aux politiques publiques. L'exemple des Rroms et Voyageurs du Poitou-Charentes (France) et de la Wallonie (Belgique). Dissertation Toulouse 2011, p. 46ff., P. 56.

- ↑ a b Cf. Jean Paul Delevoye: Report N ° 283: Accueil des gens du voyage . March 25, 1997, paragraph IA1.b: Origine et caractéristiques ; Raymonde Le Texier, Report n ° 1620 sur le projet de loi (n ° 1598) relatif à l'accueil des gens du voyage . May 26, 1999; Didier Quentin, Rapport d'information number 3212 par la comission des lois constitutionelles, de la législation et de l'administration générale de la République (PDF; 3.9 MB). March 9, 2011, p. 11f.

- ↑ Glossaire terminologique raisonné du Conseil de l'Europe sur les questions roms November 16, 2011, p. 11 [1]

- ↑ Christian Bader, Yéniches: Les derniers nomades d'Europe , Paris: L'Harmattan, 2007, p 93ff .; Remy Welschinger: Les Jenischs d'Alsace: approche d'une culture nomade marginale , dissertation Strasbourg 2007.

- ^ Joseph Valet, Les voyageurs d'Auvergne: nos familles yéniches by Joseph Valet 1990 [2]

- ↑ Two film documentaries about Yéniches in Savoy Archived copy ( Memento of the original from August 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Reproduction of the figures from Delevoye: Report N ° 283. March 25, 1997, paragraph IA1.a: Le nombre and IA2.a Essai de classification des gens du voyage ; cf. also the slightly different count in Le Texier, Report N ° 1620. May 26, 1999.

- ↑ Pierre Hérisson, Avis N ° 194 sur le projet de loi, adopté par l'Assemblée Nationale, relatif à l'accueil et à l'habitat des gens du voyage . January 27, 2000; Direction de l'habitat, de l'urbanisme et des paysages, Les aires d'accueil des gens du voyage: Préconisations pour la conception, l'aménagement et la gestion (PDF; 569 kB). November 2002, p. 5.

- ↑ Didier Quentin: Report N ° 3212. March 9, 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ Christian Bader, Yéniches: Les derniers nomades d'Europe , Paris: L'Harmattan, 2007, p. 15, who extends this assessment of the numerical share to other European countries; also Alain Reyniers, Joseph Valet: Les Jenis. In: Études Tsiganes. 1991, No. 2, pp. 11-34.

- ↑ bathrooms: Yéniches. 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Cf. Quentin: Rapport N ° 3212. March 9, 2011, p. 14ff.

- ↑ Tabular overview of the specifications and requirements in Annex 3.4-5 by Patrick Laporte, Report N ° 007449-01: Les aires d'accueil des gens du voyage ( Memento of the original of February 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet tested. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.3 MB) , Conseil général de l'Environment et du Développement durable, October 2010, pp. 49 / 54–50 / 54

- ↑ Quentin: Report N ° 3212. March 9, 2011, Annex No. 7, pp. 113f.

- ^ Ligue des droits de l'Homme: "Gens du voyage" - Guide pratique (août 2000) ( Memento of April 16, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) ; European Roma Rights Center: Always Somewhere Else: Anti-Gypsyism in France (Country Report Series, No. 15), November 2005 ( Memento of April 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) ; Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: Informations fournies par la France sur la mise en œuvre des observations finales du Comité pour l'élimination de la discrimination raciale . February 13, 2007.

- ↑ bathrooms: Yéniches. 2007, p. 94f.

Web links

- Regional languages, regional cultures, regionalism ( Memento from November 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive )