Novichok

Nowitschok ( Russian Новичок , newbie ' , emphasizing: Nowitschók ; English transcription Novichok ) is a group of strong neurotoxins and - fighting substances of the fourth generation from the 1970s in the Soviet Union developed and at least until the 1990s in Russia were further explored . The mean lethal dose of Novichok in contact with the skin is around one milligram, making it one of the strongest neurotoxins. Some of them are binary warfare agentswhose existence was unknown to the public until October 1991, but which was then made known by the participating scientist Wil Mirsajanow . The warfare agents are cited today under the code names of the Soviet and Russian developers explained below, with Novitschok being used in the narrower sense for the binary warfare agent variants. For a long time there was uncertainty about the chemical structure in the published literature, today the structures proposed by Mirsajanow in 2007 are mostly accepted.

In a broader sense, numerous other highly toxic variants, also developed in Russia, are referred to as the "Novitschok" type. What they have in common is that they inhibit acetylcholinesterase . In addition, they are designed to evade the detection procedures of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), foreign intelligence agencies and forensic experts, so that their production can be disguised as organic phosphorus compounds for agriculture or other civilian purposes.

In a broader focus of public Nowitschok moved in March 2018 in case Skripal and in August 2020 through the case Navalny .

Effect, variants and components

The neurotoxin belongs to the group of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors . Acetylcholinesterase (abbreviation AChE) is an enzyme that normally breaks down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the synapses . The neurotoxin blocks the active site of acetylcholinesterase by phosphorylation of the essential for the function of serine in the active site - a process that is irreversible, since then an aging takes place of serine.

The oximes that are effective as antidotes for other nerve warfare agents , which in a very early stage by complex formation cause the nerve agent to loosen, are at best very limited in effect in Novitschok. Atropine as well as other anticholinergics can counteract the acetylcholine flood, as they block the acetylcholine receptors of the parasympathetic system.

By inactivating the acetylcholinesterase, the breakdown of the acetylcholine is prevented, the acetylcholine flooding leads to permanent excitation with contraction of all muscles and subsequent paralysis . The victims die from the inhibition of breathing and heart muscle. Typical symptoms are foaming at the mouth, heavy secretion, vomiting and a general loss of all muscle functions.

Novichok warfare agents are based on phosphoric acid esters . Mirsajanow counts the substances A-230, A-232 and A-234 to the basic substances of the Novitschok series as well as the Russian variant of the VX (substance 33, VR). Of these, Substance 33 and A-230 received approval as chemical weapons, whereby, according to Mirsajanow, 15,000 tons of substance 33 were produced, of A-230 only experimental quantities (a few tens of tons). A-232 was also produced in experimental quantities, but not approved as a weapon, the substance was unstable according to Tucker. The binary version of the A-232 Novitschok-5 was developed and approved as a chemical weapon in 1989, but according to Mirsajanow only a few tons of it were produced. In addition, two more binary weapons were developed after Mirsajanov, an unnamed Novichok substance (approved as a chemical weapon in 1990) and Novichok-7 (tested in 1993), both produced in experimental quantities (several tens of tons). According to Mirsajanov, Novichok-5 is five to eight times more effective than VX under favorable conditions. The active ingredients of the Nowitschok group are believed to be in liquid, sometimes also in solid form, and can get into the body through injection , inhalation or transdermal application. A-230 and A-232 penetrate the blood-brain barrier and quickly get from the bloodstream to the central nervous system .

A-230 was first developed by Pyotr Petrowitsch Kirpitschow (Kirpichev) in the weapons laboratory in Schichany as a nitrogen-containing organic phosphorus compound and is a viscous liquid that crystallizes at −10 degrees Celsius (14 degrees Fahrenheit ) and thus caused problems for the planned weapon use in cold weather . Then the chemist Ugljow, who was at the institute from 1975, varied with his colleagues A-230 in the most varied of ways, including the promising candidate A-232. The molecular structure of A-232 or Novitschok-5 (the binary component) is very similar to that of A-230, with the important difference that A-230 has a direct carbon- phosphorus bond, whereas A-232 has carbon - is connected to the phosphorus atom via an oxygen atom. Tucker also names A-230 as phosphonate and A-232 as phosphate . Because the precursors and breakdown products of A-232 do not contain a direct carbon-phosphorus bond, some neurotoxin detection methods fail and the production of A-232 can be better hidden from weapons control inspections according to the CWC and foreign intelligence agencies. However, from a military point of view, A-232 has the disadvantage compared to A-230 that it is two to three times less toxic than A-230 and that it decomposes quickly on contact with water. The A-230 and A-232 were first tested in 1976 in the chemical weapons factory in Volgograd and in field tests proved to be about five to eight times more toxic than VX and its Russian variant VR.

In the 1980s, binary versions of the warfare agents emerged and became known as the actual Novichok substances, the binary version of A-232 as Novichok-5; the first binary version was developed for VR (R 33, Russian VX). These substances could also be stored better, which circumvented the problem that A-232, like A-230 in the unitary version, was unstable and not storable. Since the raw materials consist of raw materials that are also used in the manufacture of chemical products in agriculture, the weapons programs were relatively easy to disguise. According to Mirsajanov, the research program was “designed in such a way that the production of the chemicals could be concealed under the guise of legitimate, commercial production.” The strategic goal was to produce a barely detectable, highly potent and relatively safe to store neurotoxin. The new fabrics were tested between 1988 and 1993 in industrial laboratories in Russia and Uzbekistan. According to the whistleblower Mirsajanov, at least two Novichok variants have been added to the arsenal of chemical weapons of the Russian army .

Comments from developers Ugljow and Mirsajanow in March 2018

Most of the public information on the development comes from Mirsayanov, who was also used as a source in a well-known book on the history of Tucker nerve agents. One of the weapons developers, Vladimir Ugljow (* 1946 or 1947), who worked at the State Research Institute for Organic Chemistry and Technology (GosNIIOKhT) from 1972 to 1994, said in an interview in March 2018. He himself was active in the development of warfare agents until 1988 and had no first-hand information for the period after 1994. After him, hundreds of variants were developed in the tome program, but they do not come close to four substances, which he named in an interview with his own, unofficial abbreviations as A-1972 (developed in 1972 by Pyotr Kirpichev [Kirpichev], whom he describes as the main developer) , B-1976, C-1976 (both developed by himself in 1976) and D-1980 (Kirpichev, early 1980s). Ugljow did not provide any technical details in the interview and, according to his own statements, does not want to do so in the future, as he has not done in the past. According to Ugljow, one of the four substances was used for the murder of Kiwelidi (see below). They would have liquid form except for D-1980 which is powder form. The substances in the tome program (the name Novitschok was not used by the developers) were developed as alternatives to the Russian VX and each was produced in experimental doses of 20 grams to a few kilograms for test purposes, but in some cases also stored, with the whereabouts of Inventories had no information even in his active time. Since numerous variants were tried out in the 1970s and 1980s, Ugljow considers it unlikely that further developed warfare agents will emerge after his departure. He estimates that a few dozen people in Russia would know the structural formulas. He did not want to explicitly confirm the structural formulas published by Mirsajanov, but stated that the list was incomplete. According to Ugljow, a cotton ball, powder or other carrier that would have to be transported in a container that is protected against the escape of gases and coated with a solvent could be used in an assassination attempt. He did not consider Skripal and his daughter to survive if B-1976, C-1976 or D-1980 were used. He also described the four substances as particularly "tenacious". He and his colleagues would have done research on binary weapons, but to the best of their knowledge they never succeeded in completing binary weapons in the tome program, not even for the Russian VX, and he doesn't think they were used in the Skripal case either.

In 1998, in an interview with the Washington Post, Ugljow stated that binary versions had been developed. He also stated at the time that his threat to disclose technical details (structural formula) in order to support Mirsajanov was a ruse, but it worked. After his release, he made a living as a clothes dealer in the Schichany market and later lived on a small pension.

Mirsayanov confirmed in an interview in March 2018 that Uglev was a senior engineer in Kirpichev's group that developed Novichok. But Ugljow had no security clearance for binary warfare agents. Even Mirsajanov claims to have only found out about this from documents that he was officially made available during his trial (he made extensive notes at the time) and quoted them in detail in his book. According to Mirsajanow, the development of binary warfare agents is basically the next step in the development of chemical weapons. He believes the transfer to solid substrates in the form of dust is possible for the whole group of the Novitschoks, but there are no limits to the imagination, like a kind of syringe with the binary components, citing the umbrella attack as an example. He argues that research in this area is expensive, especially for large-scale implementation, and that few countries have the resources to do it, which he doubts in the case of various former Eastern Bloc countries such as Czechoslovakia. The synthesis is also not as simple as it is sometimes presented if one wants to avoid being killed immediately. There is technological information kept secret at various levels. He also confirms Uglev's statements that a few dozen, perhaps a hundred people in Russia knew about the structure, including those in the biological-medical department or the physicochemical department who would not have been able to do their work without knowing the formulas can.

Published structural formulas

The information and assumptions in the literature about the possible structures of Novitschok are contradictory and subject to great uncertainty. Often no sources are given or these are left vague and there seem to be no independent studies that verify the proposed structures, which would also require special high-security laboratories in view of the dangerousness of the substances. Chemists who were employed at government laboratories with such facilities as Robin Black from the British chemical weapons laboratory in Porton Down did not disclose any of their own findings. In 2016 he wrote about Novitschok in an overview work on chemical warfare agents: “Information about these compounds was scarce in the public literature and comes mainly from a Russian military chemist and dissident Wil Mirsajanow. No independent confirmation of the structures or properties of these compounds has been published. ”For example, Mirsayanov's structures, which he published in his autobiography in 2009, are presented in an article in Chemical Engineering News by Mark Peplow from 2018, in an article by Czech scientists Emil Halámek and Zbyněk Kobliha from 2011 (see literature, with possible synthetic routes) and Mirsajanow's structural formula for A-232 can also be found referring to this in an anthology published by RC Gupta from 2015. Jonathan Tucker writes in his book War of nerves that the British and US governments would know the structure of Novichok but refused to disclose it and put it on the list of the CWC chemical weapons control agreement for fear that terrorists or third countries with ambitions to manufacture chemical weapons could use this knowledge.

In addition to Mirsajanow, structural formulas are often cited that Steven L. Hoenig, a chemist and Chemical Terrorism Coordinator of the Florida health authorities in Miami, published in a book on chemical weapons in 2007, for which he gave no sources. Before Mirsajanov's publication, he presented different structural formulas for A-230, -232, -234 and precursor substances, which he referred to as Novitschok-5 , Novitschok-7 and another Novitschok component and for which he also indicated possible synthetic routes and even CAS Numbers . These are also reproduced in the essay by Halámek and Kobliha from 2011 alongside the formulas by Mirsajanow.

There is also a publication by D. Hank Ellison, in which various substances are listed as Novichok agents , also with CAS numbers, but A-230, A-232 and A-234 are not assigned. They correspond to the top three rows in the top of the adjacent figures, with some slightly modified substances and precursor substances also being listed.

The structural formulas presented in the top right figure can also be found similarly in specialist literature from 2014. However, as early as 1999, EM White from the Chemical Weapons Research Center of the US Armed Forces showed in comparative studies on structure-activity relationships of organic phosphorus compounds with fluorine on phosphorus, which are known as AChE inhibitors work to have a relationship between reactivity and toxicity, with structures like those proposed by Hoenig being out of the optimum for toxicity. The toxicity values (mouse, LD 50, intravenous) for the structures by Hoenig after White are 11.6 micromoles per kilogram of body weight, for sarin and cyclosarin 0.78.

Ellison's sources appear to be mainly the open Russian literature on organic phosphorus compounds from the 1970s and 1980s, according to his bibliography.

The starting point is in either case, organic organophosphate , wherein Hoenig Fluoro - phosphonates (to the phosphorus atom is other than oxygen atoms, a fluorine atom bound and it also indicates other locations more halogen - substituent ), wherein Mirsajanow fluorine phosphonic , i.e., a The nitrogen atom is bound directly to the phosphorus atom instead of an oxygen atom as in Hoenig's. Both are also imines .

A turning point was the case of Skripal in 2018. As a result, the structural formulas of Mirsajanow prevailed in publicly accessible sources. According to a report in the Dutch NRC Handelsblad on March 21, 2018, the structure of Novitschok had long been known in the West, but the Americans and British in particular had agreed to keep quiet (which can be proven from 2010 via WikiLeaks dispatches) and the substances and their precursors are also not included in the chemical annex to the international chemical weapons agreement of the OPCW (in contrast to VR, the so-called Russian VX, which is similar to the western VX and as it was already known). According to the article, an indication that it had been known in detail for a long time is that the British scientists in Porton Down were able to identify the substance relatively quickly in the Skripal case. The formulas published in the open literature may have been deliberate misinformation, according to the Handelsblad. In addition, according to the Handelsblad, leading chemical weapons experts such as Julian Perry Robinson from the University of Sussex , who published reports on chemical and biological weapons in SIPRI in the 1970s , have confirmed the correctness of the formulas published by Mirsajanov in 2009 and also runs the Handelsblad a chemist from the Dutch chemical weapons laboratory TNO Institute in Rijswijk, the late Henk Benshop. As early as 2014, Robinson told the Handelsblad that research in western weapons laboratories (such as Porton Down in England and Edgewood in the USA) was mainly about two substances, Novichok and peptides , and the then chairman of the OPCW's scientific advisory board, the Czech Jiří Matoušek , noticed in 2006 that research on Novitschok was being carried out in Edgewood. According to Wikileaks ( Cablegate 2010), in April 2010 the Americans advised the British to avoid any mention of Mirsajanov's formulas, which appeared in 2009. According to Mirsayanov, the FBI was not happy about his publication and also kept track of who bought his book, which was published by a small publisher. In Mirsajanov's opinion, the publication did not pose a threat, as it was not possible for terrorists to produce it due to extreme security requirements. The Handelsblad article also points out that the Russians may have been providing the Russians with false information about a non-existent GJ warfare agent through double agent Sergeant Joe Cassidy, who worked in Edgewood in the 1960s, where VX was developed, among other things were. The Americans would also have passed on useful information for the sake of credibility, which might have promoted the development of the Russian VX and Novichok. Mirsajanov considered this unlikely because of his knowledge of the always suspicious Soviet intelligence evaluation at the GosNIIOKhT Institute by Boris Gladstein and the working methods of the Novitschok inventor Kirpitschow. The conclusion of the Handelsblad article is: “It is now certain that the description of the Novitschoks by the Russian chemist Wil Mirsajanow in his book State Secrets from 2009 is correct. Its structural formulas are gradually being adopted in the manuals. "

An online article in Science Magazine from March 19, 2018 quotes chemist Zoran Radić from the University of California, San Diego , who has long been concerned with the mode of action of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor-based nerve agents and also of the formula of Mirsayanov goes out. He presented a molecular modeling of the mode of action of A-232 according to Mirsajanow, which, like other nerve agents such as tabun, sarin and soman, amounts to the phosphorylation of a serine. He also confirmed that the substance blends in well with the active site of the enzyme. An additional alkyl-amino group compared to the structure of the other nerve agents worries him, on the one hand with regard to the effect of the usual oximes as an antidote, and on the other hand with regard to the effect on other enzymes apart from AChE, which can later trigger neurotoxic syndromes (such as Depression, muscle weakness, nightmares, memory loss). As ionized alkylamines, their structure also suggests that they could be used as powders, while the other nerve agents were used as liquids or aerosols. UCSD pharmacologist Palmer Taylor pointed out that manufacturing would be too dangerous for his university laboratory, but that new oximes as antidotes could be worked on if the substance were made available by military laboratories.

According to Tucker, one of the two binary components of Novichok-5 contains the nitrogen component, the other the phosphorus component.According to one of the developers of the warfare agent Vladimir Ugljow, the basic substances for the production are generally commercially available and the synthesis - from the extreme danger of the synthesized Substances for your own life aside - not a big problem. According to Vasarhelyi and Földi, A-234 is a variant of A-232 in which a methyl group has been replaced by an ethyl group , and their respective binary variants can be synthesized from an organic phosphate and acetonitrile .

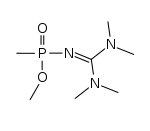

In 2016, Iranian scientists synthesized five declared Novitschok derivatives, these are O -alkyl / Aryl N - [bis (dimethylamino) methylidene] - P -methanephosphonic acid amides. The aim was to obtain chromatographic - mass spectrometric data for the control and defense against nerve warfare agents in order to improve the evaluation of analytical spectra, also beyond the specifically examined derivatives. The results were made available to the OPCW database. These substances were synthesized on a microscale , i. H. only minimal quantities were produced in order to keep the handling risk low.

The structural formula identified by the OPCW for A234, which was used in the Skripal assassination, corresponds to the formula of Mirsajanow. This will be used in a study to experimentally determine the values of hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation of A 234 by scientists at the Aberdeen Proving Ground , the research and development facility of the United States Army , in 2020. The hydrolysis rates of A 234 were the lowest, followed by the Novitschok variants A 232 and A 230, all of which were lower than the nerve agents of the V series and G series. A theoretical study on the hydrolysis mechanisms of 2020 also uses the structural formula of Mirsajanow, which also refers to the OPCW.

Novichok analogues in civil research

Some of the Novitschok structures listed in the literature (e.g. A-242 and analogs) belong to the group of the alkylhalophosphonic acid-N ', N', N ", N" -tetraalkylguanidides (Mirsajanow structures). In this context it is interesting that such substances were synthesized and investigated in 1996 at the University of Braunschweig. In contrast to Novitschok (phosphonic acid fluorides such as A-242, methanfluorophosphonic acid-N ', N', N ", N" -tetraethylguanidide), these are merely analogous phosphonic acid chlorides. Substances specifically described are, for example, tert-butylchlorophosphonic acid-N ', N', N ", N" -tetramethylguanidinide and phenylchlorophosphonic acid-N ', N', N ", N" -tetramethylguanidinide.

history

development

In May 1971, the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Central Committee of the Communist Party decided to restart the creation of fourth generation chemical weapons. Chemical weapons from the First World War such as phosgene and mustard gas belong to the first generation, the G series belongs to the second generation and poisons from the V series form the third generation. The goal was to produce a new class of nerve warfare agents with greater toxicity , stability , persistence, and easier production. This top-secret research and development program was given the cover name "Tome". The State Research Institute for Organic Chemistry and Technology (GosNIIOKhT in Moscow, Schosse Entusiastow 23, the department there also used the code name Postfach 702 ), which was subordinate to the Ministry of Chemical Industry, was commissioned with the program . The research institute was headquartered in Moscow and also operated three regional branches in Schichany , Volgograd and Novocheboksarsk . In Volgograd and Novocheboksarsk were the older production facilities for nerve warfare agents in the Soviet Union. The oldest plant was in Volgograd from the time after the end of World War II. Novocheboksarsk was opened for the production of VR (R 33) in 1972. In 1974 a fire broke out there in a warehouse, in which around fifty aircraft bombs filled with R 33 leaked. There were no immediate deaths, but several workers later died from chronic effects of the poisoning.

Novitschok was developed in 1973 by the chemist Pyotr Petrovich Kirpichov, who worked at the State Research Institute for Organic Chemistry and Technology in Schichany, district Wolsk-17. The substance was designed in such a way that it could not be detected using the methods of the time. Some of the toxin variants are estimated to be five to eight times more deadly than the neurotoxin VX and are generally more difficult to detect than other neurotoxins. Kirpitschow drew on the ideas of other Soviet military chemists and synthesized a nitrogen-containing organophosphorus nerve agent, which was originally designated as K-84 and later renamed A-230. The chemical compound was highly toxic and stable, military but only limited use at low temperatures, because the viscous liquid at -10 ° C crystallized . At that time the laboratory was under the top management of Ivan Martinov and the deputy head Viktor Petrunin, who immediately pushed the development and placed it under the top level of secrecy. Another chemist, Vladimir Ivanovich Ugljow, joined Kirpichov's research group in 1975. In the years that followed, Kirpitschow, Ugljow and their colleagues developed over a hundred structural variants of A-230 and tested them in laboratory and field experiments on animals. Most of the analogs were so unstable that they quickly lost potency, but five were sufficiently toxic and stable to be of potential military interest. These compounds were therefore subjected to intensive studies, first in Schichany and later in a special test base of the Soviet military near Nukus , Uzbekistan , which was set up in 1986 and also had a small production facility. The most promising poison turned out to be A-232.

From 1983 the Soviet Union pushed the development of binary warfare agents . Correspondingly, binary Novichok poisons were developed from the unitary compounds A-230, A-232 and A-234. Binary nerve warfare agents are, so to speak, formed in situ through a chemical reaction of two or more relatively harmless substances with one another. Since the components of the binary warfare agent were less toxic and resembled common industrial chemicals, they could escape the lists of the Chemical Weapons Convention , which was being negotiated in the late 1980s. In Moscow, Igor Wasiliev and Andrei Zheleznyakov developed a binary version of the A-232, which they named Novichok-5. Since Novitschok-5, unlike the unitary A-232, is only synthesized during use and is divided into two components by then, Novitschok-5 is more stable and can be stored longer than the unitary structural variants. The binary precursor chemicals had legitimate industrial uses and were relatively non-toxic. During production, they could be disguised under the guise of fertilizers and pesticides .

In the mid-1980s, a new plant for nerve warfare agents was built on the site of a chemical plant for civil purposes (Pavlovar factory) in northern Kazakhstan on the Irtysh River, which had been in existence since 1965 , and parts of the production were relocated there from Novocheboksarsk, especially for Novichok warfare agents . This happened in a shielded part of the factory (called No. 2). There were production facilities there for the starting materials for the production of nerve agents, in particular phosphorus trichloride, and intermediate products and the binary components of warfare agents of the Novichok series. Large reactors made of corrosion-resistant alloys with a high nickel content ( Hastelloy ) or with an inner lining made of silver were built. There were also buildings with laboratory animals for testing the warfare agents. In 1987 the construction of the plant for the highly toxic end products was stopped and the other plants in No. 2 were converted for civil purposes by 1992. Novichok compounds had already been produced in experimental quantities in the older factories in Volgograd and Novocheboksarsk. Pavlovar was not declared a chemical weapons factory by the CWC in 1989/90, not even by Kazakhstan. The production of phosphorus trichloride continued and until 1992, for example Folitol -163 (CF 2 = CF- (CF 2 ) 7 -O-CH 2 -CF 2 -CHF 2 ) was produced in the now civil plant No. 2 , an organic one Fluorine compound to protect underground electric motors from contact with oils and water at high temperatures, Gidrel (used to control plant growth and an organic phosphorus compound ), acrylates and IOMS , an organic phosphorus compound that has been widely used to prevent salt formation To prevent pipes for example for water supply or heat exchange. IOMS did not fall under the substances declared by the CWC (Schedule 2), because it has more than one carbon atom on phosphorus, Gidrel with only one carbon atom on phosphorus does. Partial privatizations took place in the 1990s, and the factory subsequently ran into financial difficulties because there was no government support, Russian competitors were cheaper and more expensive chlorine had to be bought from Russia.

In April 1987, the Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev publicly announced that the Soviet Union would stop producing chemical weapons and convert its existing chemical military facilities to civilian use. Despite Gorbachev's promise, the Soviet Union continued the secret development and testing of Novichok binary warfare agents. In 1989 and 1990 open-air experiments with Novichok-5 took place on the Ustyurt plateau . Even after the program became popular in the early 1990s, the Novichok series was further developed. In the fall of 1993, the chemist Georgi Droscht discovered a new chemical compound, which he called Novitschok-7, which was ten times more deadly than Soman , but had a similar volatility . Several tons of Novichok-7 were produced and tested in Schichany and at Nukus. Two other binary Novitschok versions, Novitschok-8 and Novitschok-9, were developed and were ready for production.

Uzbekistan learned of the chemical weapons program only after its independence from the Soviet Union. In 1993 the last Russian scientists left the test facility in Nukus in the north of the country. Uzbekistan then negotiated with the United States for assistance with dismantling and decontamination . In 1999, American specialists were involved in decontaminating the plant in Nukus.

revelation

In the course of the bilateral negotiations on the Chemical Weapons Convention between the United States and Russia, the Novitschok series and its further development into a binary warfare agent were kept secret. The existence of the novel neurotoxins was only revealed in the early 1990s by the Russian chemist Wil Mirsajanow . Mirsajanov worked at the Moscow headquarters of the State Research Institute for Organic Chemistry and Technology, which was tasked with running the "Tome" program. He was an expert in analytical chemistry, monitored toxic emissions from the laboratory to the environment, but was not directly involved in development. He was later promoted to head of the technical counterintelligence department and ensured that foreign spies could not discover any traces of production. In the spring of 1990, when taking measurements outside the facilities, he found that the concentration of lethal substances was 50 to 100 times higher than the maximum allowable concentration. Mirsayanov told several superiors that the contamination around the research facilities was a major source of danger for the local population and scientists. However, he was instructed to leave the subject alone.

In 1991 Mirsayanov went public. He was convinced that the Soviet Union would continue to hide the existence of the weapons program so that it would not have to be declared and disposed of under the future Chemical Weapons Convention. In October 1991 he wrote in a Moscow newspaper that the Soviet Union had secretly developed a new class of extremely toxic nerve warfare agents - despite Gorbachev's allegation that it had ceased manufacturing chemical weapons in 1987. Mirsayanov was then fired, but otherwise little attention was paid to his article. On September 12, 1992, together with the chemist Lev Fyodorov, he published a second article entitled "A Poisoned Politics" in the Moskovsky Novosti newspaper . He also gave an extensive interview to the Baltimore Sun. On October 22, 1992, Mirsajanov was arrested by the Russian domestic secret service, detained in Lefortovo Prison and later placed under house arrest. Although he had not revealed any technical details about the "Tome" program, he was accused of divulging state secrets. Fyodorov was also arrested but released. At that time there was considerable pressure from foreign scientists and the situation was legally dubious, as prosecution based on secret lists of the Soviet Union was forbidden at the time and a law specifically enacted by Prime Minister Chernomyrdin on the occasion of the Mirsayanov case was applied retrospectively in contravention of general legal principles (and officially that Project was denied). The director of GosNIIOKhT Viktor Petrunin and the generals Anatoly Demjanowitsch Kunzewitsch and Igor Yevstavyev (Igor Yevstavyev) secretly received the 1991 Lenin Prize for the successful industrial production of Novichok warfare agents.

Vladimir Ugljow (Vladimir Uglev), who together with Pyotr Kirpitschow had developed the warfare agent Novichok, gave an interview to the magazine Novoje Vremja on February 4, 1993 . In it he confirmed Mirsajanov's accounts and revealed his own involvement in the chemical weapons program. Since he held a political office at the time, he enjoyed immunity from prosecution. Mirsayanov was charged in Moscow on January 24, 1994, but the trial was dropped on May 11, 1994 for lack of evidence. In 1995 he emigrated to the United States and settled in Princeton. The existence of the Novichok series had been unknown to Western intelligence services before Mirsayanov's revelations. In 2018, Ugljow, now a pensioner in Anapa on the Black Sea, gave an interview in which he confirmed that he had been the developer of two of the warfare agents in 1976. Novitschok (newcomer) was the name after him that the civilian employees who were not directly involved in the development gave the new types of military warfare agents. Ugljow went on to say that the warfare agents were in liquid form, except for one that could be brought into powder form. On one occasion a flask containing the dangerous substances exploded in his laboratory and he was very afraid, which, according to Ugljow, would also be one of the first symptoms of poisoning.

Mirsajanov published his book in 2009, which, in addition to insights into the intrigues and nepotism at his Moscow institute and the ambitions of high chemical weapons generals, also revealed technical details. He had already published a Russian version in Tatarstan in 2002 (he is proud of his Tatar ancestry), but when it was leaked that he wanted to publish technical details for the English version, his co-author Amy Smithson (a political scientist and chemical weapons expert) dropped out. and he couldn't find a publisher, so he had to self-publish the book at his own expense. In contrast to Ken Alibek's 1999 revelations about Soviet biological weapons ( Biohazard , Random House), the book found next to no response from the American public. The western authorities that had defended him on his indictment in Russia from 1992 to 1994 remained silent and there was only one review that criticized him for having published the technical details out of anger that the substances were not in the appendices of the Chemical Weapons Agreement emerged. After Mirsayanov, no one at Princeton was interested in its publication. In contrast, Fyodorov, with whom Mirsajanov later fell out, had published the structure of the Russian VX as early as 1993, which was easily adopted in Western literature, but the material was similar to the American VX and therefore no secrecy was required. He also appears on the OPCW lists, while Novichok was ignored by the OPCW to the public. When the British chemical weapons expert Julian Perry Robinson published an almost correct guess about the structure in 2003, he was reprimanded by British officials, which had not happened to him before (as early as 1970 he published a correct guess about the structure of the then secret VX in a brochure the WHO). According to Robinson, the secrecy about the structure has less to do with fear of terrorists, for whom the substance is too dangerous and who have much easier options, than with the protection of the chemical weapons agreement and a secret understanding between Russia and the USA.

Early knowledge of Novitschok from the Federal Intelligence Service

According to media reports from May 2018, the German secret service BND had already procured a sample of one of the Novitschok variants in the early 1990s by guaranteeing a Russian scientist and his family the right to stay in Germany in exchange for the sample. Chancellor Helmut Kohl was informed, but only a few people besides. In order to forestall legal and political concerns, the sample was not kept, but was analyzed under strict secrecy in Sweden and then the closest western allies were informed of the results. The wife of the Russian scientist, who spied for the BND, hid a Novichok sample in a box of chocolates and brought it to Sweden on a passenger plane from Russia. The woman had relatives there, so the trip went unnoticed. The handover was organized by the Swedish security police , Säpo , who then took the sample by train around a thousand kilometers further to the chemical weapons center in northern Sweden. Swedish chemical weapons experts analyzed the warfare agent and later destroyed it. As agreed, the German authorities were informed of the result of the analysis. Instead of scoring points with the Allies with this success, the Federal Government and its intelligence service had to take note of the fact that they were already informed, but had kept their own findings secret from the Federal Government. After all, the BND was then involved in a NATO working group in which the USA, Great Britain, Canada, the Netherlands and other countries also took part, but which soon disbanded.

Analytics

Due to the large number of substances characterized by the structural formulas, there are so far only a few publications on reliable analysis. First publications could show that infrared spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy , coupled with mass spectrometry , are suitable for reliably detecting the Novitschok structures.

Scientists at the US Army Chemical Weapons Laboratory, based on the structural formulas of Mirsajanow, use multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and gas chromatography with mass spectrometry coupling (GC-MS) as the detection method . For the verification of the detection methods, however, the synthesis of small amounts of the substances in question is necessary (this is permitted according to the OPCW rules), which is only possible in certified high-security laboratories, often military laboratories with the appropriate specialist knowledge of chemical warfare agents.

This is to be distinguished from routine medical evidence of general poisoning by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

Known cases of poisoning

Andrei Zheleznyakov (1987)

The Russian chemist Andrei Zheleznyakov experimented with Novichok-5 in May 1987 at the Moscow State Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology. He varied the temperature as the binary components reacted in a small reactor made of corrosion-resistant steel and took samples via a small syringe connected to a plastic tube that accidentally came off, causing the substance to escape. Although he was able to stop the leak quickly, he noticed the first symptoms (dizziness, ringing in the ears, orange dots in visual perception). He was also extremely afraid. Colleagues noticed his condition, took him out into the fresh air, gave him a vodka and escorted him to the bus home. At the bus stop, he hallucinated, passed out and collapsed, a friend brought him back to the institute. The institute's KGB officer made sure that he came to the leading Soviet center for poisoning, the Sklifossovsky Institute in Moscow, where the doctor was sworn to secrecy and the patient was registered with food poisoning. The doctor noticed that the concentration of acetylcholinesterase in the body had dropped sharply, but was able to stabilize it with antidotes such as atropine, so that after ten days in a critical condition he slowly regained consciousness. After another week in the intensive care unit, he came to the Institute of Industrial Hygiene and Occupational Pathology in Leningrad, which had a secret department for such poisoning cases (one of three such departments in the Soviet Union, the others were in Volgograd and Kiev, known as the special department for tome problems). Zheleznyakov stayed there for three months. He was unable to walk, suffered from chronic arm weakness, hepatitis with subsequent cirrhosis of the liver , epilepsy , attacks of depression and inability to read or concentrate. Zheleznyakov recovered slowly, but remained unable to work and died five years later in 1992 due to his generally deteriorating health.

Iwan Kiwelidi (1995)

Kiwelidi was President of Rosbisnesbank in 1995. As a representative in business associations, he railed against the evil of corruption . He died on August 1, 1995 after a stranger put Novichok on his telephone receiver . When Kiwelidi showed signs of intoxication, his secretary called an ambulance on the same phone; she died too. The morgue doctor also died after Kiwelidi's autopsy. According to a former employee of the Russian military intelligence service GRU Vladimir Kozhelev, Kivelidi and his secretary were killed “with a drop containing a tenth of a milligram of Novichok” .

According to Vladimir Ugljow (Vladimir Uglev), one of the leading Novichok developers at the Russian GosNIIOKhT laboratory (in which Leonard Rink also worked, see below), the poison, absorbed in a cotton ball, is on the microphone in the telephone receiver in Kiwelidi's office -Telephone been rubbed.

In March 2018, Novaya Gazeta published an article in which details of the then partially secret trial of the murder of Kiwelidi were published. It also publishes a structural formula for the substance used at the time from the trial files and classifies the substance as a Novitschok variant. A former employee (Leonid Rink) of an institute for chemical weapons synthesized the substances and sold them to the underworld, he had also confessed to a secret interrogation and was sentenced to one year in prison for it. The newspaper article also takes the Russian view that there was no Novitschok project, but that this was just a collective term for various highly toxic substances and that Novitschok-like substances found their way into the underworld even then. Some of Rink's sentences were removed from the online version of the article because they contradicted Moscow's view that Novichok was not the name of an official chemical weapons project. Vladimir Ugljow, who was involved in the development of warfare agents in the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s, also confirmed in March 2018 that a Novichok-type neurotoxin was used.

Emelyan Gebrev (2015)

The arms dealer Emilian Gebrew was allegedly poisoned with Novichok warfare agent in Bulgaria and survived.

Sergei and Julia Skripal and two other people (2018)

According to the British government, an active ingredient from the Novichok Group was used in the attack on March 4, 2018 on Russian defector and British double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Julia Skripal. Prime Minister May accused Russia of either being behind the crime or of losing control of its military agents. In this context, the substance group received great international attention. The Russian chemist Wil Mirsajanow, who unveiled the Novichok program in the early 1990s, said in the United States on March 13, 2018 that Russia had strict controls on its Novichok supplies and that the warfare agent could be used as a weapon for non-state actors is too complex. In his opinion, only Russia could be considered responsible. The Russian government declined responsibility for the attack. According to information that can be traced back to the Russian ambassador in London Alexander Jakowenko, the British government believes that it is variant A-234, but this has not been publicly confirmed by the British government.

The director of Porton Down's DSTL research institute , Gary Aitkenhead, announced on April 3 that his laboratory had identified the poison as military-grade Novichok , but the exact origin had not been established. Because of the complexity of the production, however, he expressed his conviction that a state would stand behind it.

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) announced on March 16, 2018 in The Hague that no state party had ever declared this chemical warfare agent. The UK government agreed to an independent investigation by the OPCW in March 2018. On April 12, the OPCW confirmed the British findings on the neurotoxin used in a preliminary statement without mentioning the name Novichok. They also confirmed a high degree of purity with almost no impurities. According to the OPCW, the substance is very stable, even if it is exposed to the elements. All four OPCW research laboratories found the same Novitschok variant, whereby the structure corresponds to the formulas known to the public. Contrary to what Russia claims, no physical comparison sample was necessary for the complex identification. It is a sparingly water-soluble liquid with a high boiling point, which hardly evaporates even in summer temperatures and is hardly dissolved by the rain.

On July 5, 2018, British police announced that another Novichok poisoning case had occurred near Salisbury. A British couple collapsed one after the other in their shared apartment in Amesbury on June 30, 2018 and were admitted to the local hospital in critical condition. The police considered a connection with the Skripal case to be possible, for example contact with the previously not found container with which the poison in the Skripal case was transported. According to the British police, there was no evidence of a targeted attack from the background of the two victims. Both were unemployed and addicted to drugs, and the man was known for rummaging through garbage cans on occasion. The woman died on July 8, 2018. The authorities opened a murder investigation into her case . Your partner regained consciousness, but was then in a critical, if stable, state. On July 13, 2018, the police reported that a vial had been found in the man's house by forensics, which, according to investigations by Porton Down, contained Novichok. The poisoned man told his brother that “he picked up the perfume bottle somewhere and then got sick”. As the male victim later recalled, the bottle was in a small cardboard box and had a pump attachment for spraying. It contained a very oily, odorless liquid. The male victim immediately washed the liquid off his hands, the woman sprayed it on her wrists and rubbed the liquid on. She complained of a headache a quarter of an hour later and then fell into a coma.

In April 2018, the General Secretary of the OPCW Ahmet Üzümcü proposed that Novichok be included in the list of prohibited nerve agents maintained by the organization. This was implemented in November 2019.

Alexei Navalny (2020)

According to the German government, the Russian politician and dissident Alexei Navalny was poisoned with Novitschok. On August 20, 2020, he boarded a plane to Moscow in Tomsk, Siberia , initially felt uncomfortable and shortly afterwards passed out, which is why the plane made an emergency landing in Omsk . After a phase of diplomatic tug-of-war, Navalny, who had meanwhile been put into an artificial coma, was flown to Berlin on August 22 and treated there by doctors from the Charité . They diagnosed that Navalny had been poisoned by a substance from the group of cholinesterase inhibitors. On September 2, the federal government announced that a special laboratory of the Bundeswehr (Bundeswehr Institute for Pharmacology and Toxicology, Munich) had detected a nerve agent from the Novitschok group. The poison was found in the blood, urine and skin samples of Navalny and on a bottle that Navalny carried with him on his trip and that the relatives had seized. According to the statement by the President of the Federal Intelligence Service, Bruno Kahl, which was reproduced in the Spiegel , it is supposed to be a further development of the previously known Novitschok forms, even "harder" than the previously known forms. The composition makes it likely for the federal government that state agencies in Russia are involved. The use of a poison from the Novichok group has been independently confirmed by French and Swedish specialist laboratories, and the OPCW has also received samples for analysis in some of their reference laboratories.

literature

- Steven L. Hoenig: Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents . Springer, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-387-69260-9 , pp. 79-88 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Mark Peplow: Nerve agent attack on spy used 'Novichok' poison. Chemical and Engineering News, Volume 96, Issue 12, 2018, p. 3.

- Vil S. Mirzayanov: State Secrets. An Insider's Chronicle of the Russian Chemical Weapons Program . Outskirts Press, Denver 2008, ISBN 978-1-4327-2566-2 .

- Emil Halámek, Zbyněk Kobliha: Potential chemical warfare agents. Chemicke Listy, Volume 105, No. 5 (May), 2011, pp. 323-333 (Czech), online

- Jonathan B. Tucker: War of nerves: chemical warfare from World War I to al-Qaeda . Anchor Books, New York 2006, ISBN 978-1-4000-3233-4 ( full text at Archive.org).

Web links

- Lev Fedorov: Chemical Weapons in Russia: History, Ecology, Politics . Moscow, Center of Ecological Policy of Russia, July 27, 1994.

- Russian chemical weapons , Federation of American Scientists .

- This is how the Soviet Union developed the Novichok neurotoxins. sueddeutsche.de March 14, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 231-321.

- ↑ Stephanie Fitzpatrick: Novichok . In Eric A. Cody, James J. Wirtz, Jeffrey A. Larsen (Eds.): Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia of Worldwide Policy, Technology, and History . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara 2005, ISBN 978-1-85109-490-5 , pp. 201-202 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Inge Schuster: Novitschok - nerve poison from the point of view of a chemist. In: Scienceblog.at. Institute for Science Outreach, May 3, 2018, accessed on July 21, 2020 .

- ^ Poison attack on ex-spy: Skripal case - Moscow defends itself . In: Tagesschau. March 13, 2018.

- ↑ Pohanka M: Diagnoses of Pathological States Based on Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase. , Curr Med Chem. 2020; 27 (18): 2994-3011, PMID 30706778

- ↑ a b c d Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 233.

- ↑ The spokesman for the federal government: Statement by the federal government in the Navalny case. In: bundesregierung.de. September 2, 2020, accessed September 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Vil Mirzayanov: Dismantling the Soviet / Russian Chemical Weapons Complex: An Insider's View . In Chemical Weapons Disarmament in Russia: Problems and Prospects , Henry L. Stimson Center, 1995, p. 24. A table overview is on p. 25.

- ↑ a b Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 253.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 234.

- ↑ Ramesh Gupta (Ed.) Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents, Academic Press 2015, p. 340. The formula on the right corresponds to that which Mirsajanow stated in his 2009 book. The formula on the left is a suggestion for A-232 in an older book by Steven Hoenig, Compendium of chemical warfare agents . Springer, New York 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 232.

- ↑ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 233. According to Mirsajanow's formula, A-232 (and A-234) also has no direct connection between phosphorus and carbon, in contrast to the well-known nerve warfare agents tabun , sarin , soman , whatever was an important identification mark for gun inspectors.

- ↑ a b Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 253-254.

- ↑ Ivo Mijnssen: The Soviet Union once developed the neurotoxin Nowitschok. Its trace remains a mystery to this day , NZZ.ch from March 13, 2018, accessed on March 15, 2018.

- ↑ The scientist who developed “Novichok” , interview with Svetlana Richter, The Bell, March 2018.

- ↑ David Hoffman: Soviets Reportedly Built Weapon Despite Pact , Washington Post, August 16, 1998.

- ↑ Interview by Ugljow, Christian Esch, Deadly Drops in the Telephone Receiver, Spiegel Online, March 25, 2018.

- ↑ Interview by Mirsajanow, Komersat FM, March 21, 2018 (Russian).

- ↑ Information on these compounds has been sparse in the public domain, mostly originating from a dissident Russian military chemist, Vil Mirzayanov. No independent confirmation of the structures or the properties of such compounds has been published. Black, Development, Historical Use and Properties of Chemical Warfare Agents. In: Franz Worek, John Jenner, Horst Thiermann (eds.): Chemical Warfare Technology. Volume 1, Royal Society of Chemistry 2016, Issues in Toxicology No. 26, p. 19.

- ↑ Mark Peplow: Nerve agent attack on spy used 'Novichok' poison . Chemical & Engineering News , Volume 96, Issue 12, 2018, p. 3.

- ↑ Ramesh C. Gupta (ed.): Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents . Academic Press, 2009, 2015, in it the article: Jiri Bajgar, Jiri Kassa, Josef Fusek, Kamil Kuca, Daniel Jun: Other Toxic Chemicals as Potential Chemical Warfare Agents. P. 340.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 380.

- ^ Hoenig, Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents .

- ^ Hoenig, Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents. P. 79: have recently been cited in the literature with reference to their chemical structure but with no analytical data.

- ↑ D. Hank Ellison: Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents . CRC Press, 2008, pp. 37-42.

- ↑ Balali-Mood, Abdollahi (Ed.): Basic and clinical toxicology of organophosphorous compounds . Springer 2014, p. 15.

- ^ EM White, Effects of chemical reactivity on the tosicity of phosphorus fluoridates, SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research, Volume 10, 1999, pp. 207-213. Hoenig's structures correspond to No. 12 in Figure 2 on p. 210, the toxicity-reactivity relationship is shown in Figure 3, p. 211. The relative energy for the intermediate stages are too high and they therefore react more slowly. G-warfare agents such as sarin and soman, on the other hand, are close to the optimum.

- ↑ White explicitly lists the substance (in his case No. 12), which is listed here in the illustration of the structures according to Hoenig / Ellison in the top row on the left. They also form the basic framework for Hoenig's proposals for A-230, -232, -234, where a terminal chlorine is replaced by fluorine. The toxicity values resulted from the extensive ERDEC data from investigations of numerous substances on a special laboratory mouse strain at the Edgewood Chemical Weapons Research Center, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s

- ↑ D. Hank Ellison: Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents . CRC Press, 2008, pp. 101ff.

- ↑ Mark-Michael Blum: Chemical Regulation - An Unknown Nerve Poison , News from Chemistry 68 (September 2020) pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Karel Knip: 'Onbekend' zenuwgas novitsjok was allang bekend , Raam op Rusland, March 20, 2018 (Dutch), NRC Handelsblad.

- ↑ Karel Knip: "Unknown" newcomer Novichok was long known. Handelsblad (online edition), March 21, 2018. It is now certain that the description given by the Russian chemist Vil Mirzayanov in 2009 of the novichoks in his book 'State Secrets' is correct. His structural formulas are gradually being copied into manuals , in the English version.

- ↑ Richard Stone: UK attack shines spotlight on deadly nerve agent developed by Soviet scientists , Science, March 19, 2018; doi: 10.1126 / science.aat6324 .

- ↑ Deadly drops in the telephone receiver , Spiegel Online, March 25, 2018.

- ↑ György Vasarhelyi, Laszlo Földi: History of Russia's Chemical Weapons, AARMS, Volume 6, 2007, pp. 135–146, here p. 141. AARMS = Applied Research in Military Science , later renamed Academic and Applied Research in Public Management Science , National University of Public Service (NUPS), Budapest. They refer to L. HALÁSZ, K. NAGY: Chemistry of toxic substances, Miklós Zrínyi National Defense University 2001, pp. 47–59 (Hungarian).

- ↑ Hosseini SE, Saeidian H, Amozadeh A, Naseri MT, Babri M: Fragmentation pathways and structural characterization of organophosphorus compounds related to the Chemical Weapons Convention by electron ionization and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry . In: Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry . tape 30 , no. 24 , October 5, 2016, doi : 10.1002 / rcm.7757 .

- ↑ Ryan De Vooght-Johnson: Iranian chemists identify Russian chemical warfare agents , spectroscopynow.com from January 1, 2017, accessed on March 28, 2018 (English).

- ↑ Steven Harvey, Leslie MacMahon, Frederic J. Berg, Hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation of Novichok nerve agents, Heliyon, Volume 6, 2020, p. E03153

- ↑ The hydrolysis was measured in M per minute at 25 degrees Celsius in 50 mM bis-tris-propane buffer, pH 7.2. A 234 0.0032, A 232 0.061, A 230 0.17, VX 0.246, VR 0.237, Sarin (GB) 6.68

- ↑ Y. Imrit, P. Ramasami et al. a., A theoretical study of the hydrolysis mechanism of A-234; the suspected novichok agent in the Skripal attack, RSC Adv., 10, 2020, 27884

- ↑ Schmutzler R: Synthesis, structure and some reactions [N- (N ', N', N ”, N” -tetramethyl) -guanidinyl] -substituted phosphoryl compounds. , Journal of Inorganic and General Chemistry 1996; 622 (2): 348-354

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 231-232.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 231.

- ↑ a b Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 233-234.

- ↑ a b c Assassination attempt on ex-spy Skripal: What is the neurotoxin Novitschok? In: Spiegel Online . March 13, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed March 13, 2018]).

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 273.

- ^ Vadim J. Birstein: The perversion of knowledge: the true story of Soviet science . Westview, Boulder 2004, ISBN 978-0-8133-4280-1 , p. 95 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Hoenig, Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents. P. 79: Here with Novitschok-5, Novitschok-7 u. a. on the other hand, denotes the components that make up the A-series, in the case of A-232 this is Novitschok-5.

- ^ Hoenig, Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents. Pp. 79-88.

- ↑ Gulbarshyn Bozheyeva: The Pavlovar Chemical Weapons Plant in Kazakhstan: History and Legacy. The Nonproliferation Review, Summer 2000, p. 136.

- ↑ External identifiers or database links for 2-chloroethylphosphonic acid dihydrazine : CAS number: 74968-27-7, PubChem : 156822 , ChemSpider : 138056 , Wikidata : Q82988267 .

- ^ OPCW, Chemical Weapons Convention, Annex of Chemicals, Schedule 2

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 321.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 273, 299, 321.

- ^ World: Asia-Pacific US dismantles chemical weapons . August 9, 1999 ( bbc.co.uk [accessed March 15, 2018]).

- ^ Judith Miller: US and Uzbeks Agree on Chemical Arms Plant Cleanup . In: The New York Times. May 25, 1999.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 299-301.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 315-317.

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, p. 315.

- ↑ Frank von Hippel, Russian whistleblower faces jail, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 1993, p. 7.

- ↑ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 320-321.

- ↑ Mirzayanov, The (agent) fate of Novichok, CBRNe World, Summer 2009, p. 28.

- ↑ a b RHC Handelsblad, March 21, 2018.

- ^ Holly Porteous, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Volume 23, 2010, p. 537.

- ↑ Western silence about novichoks is related to the protection of the chemical weapons convention. Better an incomplete convention than no convention. RHC Handelsblad, March 21, 2018.

- ^ "BND procured nerve agent" Novitschok "in the 1990s" Sueddeutsche Zeitung, May 16, 2018.

- ^ BND procured a sample of Nervengift Nowitschok , Spiegel Online, May 16, 2018.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe, Nowitschok im Schlafwagen, Der Spiegel, No. 25, June 16, 2018, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe, Allies knew about Novitschok even before the BND , Spiegel Online, May 18, 2018.

- ^ Allies knew before the BND von Novitschok , Der Spiegel, No. 21, 2018, p. 22.

- ↑ Tan YB, Tay IR, Loy LY, Aw KF, Ong ZL, Manzhos S: A Scheme for Ultrasensitive Detection of Molecules with Vibrational Spectroscopy in Combination with Signal Processing. , Molecules. 2019 Feb 21; 24 (4): 776, PMID 30795561

- ↑ Nakano Y, Imasaka T, Imasaka T: Generation of a Nearly Monocycle Optical Pulse in the Near-Infrared Region and Its Use as an Ionization Source in Mass Spectrometry. , Anal Chem. 2020 May 19; 92 (10): 7130-7138, PMID 32233421

- ↑ Harvey SP, McMahon LR, Berg FJ: Hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation of Novichok nerve agents. , Heliyon. 2020 Jan 7; 6 (1): e03153, PMID 32042950

- ^ Tucker, War of Nerves , 2006, pp. 273-274.

- ↑ welt.de October 13, 1997: Jens Hartmann, The time when King Mammon swung the scepter

- ^ Attack on ex-spy Skripal. Use of neurotoxin Novichok completely destroys the Russian-British relationship , handelsblatt.com, March 13, 2018.

- ↑ Christian Esch: Deadly drops in the telephone receiver , Spiegel Online, March 25, 2018.

- ^ Diepresse.com: Poison affair: Russian chemist passed Novichok on to criminals. - Hundreds of fatal doses of a neurotoxin were sold for $ 1,500 or $ 1,800 in the mid-1990s, according to a Russian newspaper.

- ↑ Novichok nerve agents were used in 1995 killing, ex-Russian agent says , English article in euronews.com, March 13, 2018.

- ↑ The major stories you need to understand Russia , English article in THE BELL, March 21, 2018.

- ↑ Novichok has already killed («Новичок» уже убивал). Russian article in Novaya Gazeta, March 22, 2018.

- ↑ a b Yasmeen Serhan, Siddhartha Madhanta: What Russian Scientists Are Saying About Nerve Agents , The Atlantic, March 22, 2018.

- ↑ Investigative journalists link third Salisbury attack suspect to poisoning of Bulgarian arms dealer , Meduza , February 9, 2019.

- ↑ The Insider and Bellingcat spoke about eight GRU employees who were involved in the poisoning of a Bulgarian entrepreneur by Novichok , Novaya Gazeta, November 24, 2019.

- ↑ Gift Test , Novaya Gazeta, November 26, 2019.

- ↑ Assassination attempt on ex-spy Skripal: The US Secretary of State also accuses Russia . In: Spiegel Online . March 13, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed March 14, 2018]).

- ↑ May blames Russia for the attack . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. March 12, 2018.

- ^ Joseph Ax: Only Russia could be behind UK poison attack: toxin's co-developer . In: Reuters. March 13, 2018. With video (1:17) of the interview and from the production of Novitschok.

- ↑ Michael Stabenow and Reinhald Veser: Traces of a deadly poison , faz.net, March 16, 2018.

- ↑ What are Novichok nerve agents? In: BBC News . March 19, 2018 ( bbc.com [accessed March 24, 2018]).

- ↑ http://www.dw.com/de/gro%C3%9Fsites-macht-weiter-russland-f%C3%BCr-skripal-attenat-verendung/a-43239992 , Deutsche Welle, April 3, 2018.

- ↑ Porton Down experts unable to verify precise source of novichok , The Guardian, April 3, 2018.

- ↑ poison attack on Skripal. Boris Johnson blames Putin for the attack , welt.de, March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Laura Smith-Park, Simon Cullen: 'Pure' Novichok used in Skripal attack, watchdog confirms , CNN, April 12, 2018.

- ↑ Christian Esch, Fidelius Schmid, Mysteriöser Unfall, Der Spiegel, No. 28, July 7, 2018, p. 86. They also refer to the previously secret twelve-page long version of the OPCW report.

- ↑ Der Spiegel No. 28, 2018, p. 86.

- ↑ English couple poisoned by Novitschok , Tagesschau Online, July 5, 2018.

- ↑ Amesbury poisoning: Couple exposed to Novichok nerve agent , BBC Online, July 5, 2018.

- ↑ Der Spiegel, No. 28, July 7, 2018, p. 86.

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel: Woman poisoned with Novitschok died. Retrieved July 8, 2018 .

- ↑ UPDATE: Source of nerve agent contamination identified . In: Metropolitan Police news page , July 13, 2018, accessed July 13, 2018.

- ↑ Novitschok may have been sacrificed in a perfume bottle orf.at, July 16, 2018, accessed July 16, 2018.

- ↑ Lena Obschinsky, Novitschok victim speaks about poisoning, Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung, July 27, 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ Reinhard Veser: OPCW rejects Lavrow's criticism , faz.net, April 19, 2018.

- ↑ OPCW puts neurotoxin Novitschok on the list of prohibited substances. Der Standard , November 28, 2019, accessed the same day.

- ↑ + Chemical weapons treaty bans novichok , Nature, Volume 576, December 5, 2019, p. 27.

- ^ Statement by the Federal Government in the Navalny case. Retrieved September 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexander Chernyshev u. a .: According to Nowi-Schock , Der Spiegel, No. 37, September 5, 2020, p. 38

- ↑ Maik Baumgärtner u. a., Shot in the own knee, Der Spiegel No. 38, September 12, 2020, p. 24

- ↑ Charité: Nawalny's condition has improved - he can temporarily get out of bed , Handelsblatt Online, September 14, 2020