Post, telephone and telegraph companies

| Post, telephone and telegraph companies

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | public services |

| founding | 1928 |

| resolution | January 1, 1998 |

| Reason for dissolution | European liberalization of telecommunications |

| Seat | Bern |

| management | Jean-Noel Rey ( General Manager ) |

| Number of employees | 58,431 |

| sales | 1.6 billion Swiss francs |

| Branch | Post , telecommunications |

| Status: 1997 | |

The Swiss PTT (Post, Telephone and Telegraph Company) was the state authority for post , telephone , telegraph and fax operations in Switzerland and Liechtenstein between 1928 and January 1, 1998 . The forerunner of the PTT was the Swiss Post, which was founded in 1847 during the Sonderbund War . With the entry into force of the Constitution of the Swiss Confederation in 1848, the Post was placed under state supervision and transformed into the Federal Post. Towards the mid-1880s, the Federal Post turned to building a telephone network under Alexander Graham Bell's system. In the 1920s, efforts were made to unite the post and telegraph directorates of that time. This came about in 1928 with the founding of the PTT. In both World War II and World War I , the PTT was intensely busy delivering mail to internees . In the course of the European liberalization of telecommunications , the PTT were dissolved on January 1, 1998 and their tasks were transferred to the Swiss Post and Swisscom .

history

Postal system in the Helvetic Republic

In 1798 the old confederation collapsed under the military and political pressure of France . As of April 12, 1798, the Helvetic Republic replaced the loose structure of the 13 cantons with their locations as a central state. Following the mercantilist logic, the postal system should only be controlled by the central state. A first attempt to centralize the cantonal postal companies was not made by the Great Council (today : National Council), but by the board of directors in Aarau (government, today : Federal Council in Bern) with the postal service dress regulations of May 5, 1798. The legal basis, that Postregal , only received legal force from September 1, 1798 by the Grand Council and the Senate (today: Council of States). Organizationally, the Helvetian Post took shape from November 16, 1798 with the law on the establishment of a "direct mail administration" and the establishment of uniform postal taxes. The location of the central postal administration proved problematic. Because in 1798 there was no permanent seat of government for the republic. The capital should alternate between Aarau, Lucerne, Basel, Zurich and Bern.

The centralization of the post provided for the creation of five post districts. The first postal district was Basel. The second Zurich postal district included the Zurich , Baden , Aargau , Graubünden , Glarus , Waldstätten , Bellinzona and Lugano regions . St. Gallen with the cantons of Säntis and Linth was the third postal district. The fourth postal district of Schaffhausen , encompassing the same canton, was followed by the fifth postal district of Bern with the areas of Bern , Oberland , Léman , Friborg , Solothurn and Wallis . However, the canton of Valais was briefly a republic of its own from 1802 when it was separated from the Helvetic Republic.

As a result of internal unrest by federalist-minded insurgents (" Stecklikkrieg ") in the summer of 1802, the Helvetic Republic was given only a short duration. General and First Consul Bonaparte - from 1804 Emperor Napoleon - intervened in 1802 and had cantonal sovereignty restored through the act of mediation. During the mediation period (1803–1815), the central state changed into a loose confederation of 19 cantons (excluding Geneva, Valais, Neuchâtel, the dioceses of Basel and Biel). Central power was reduced to a minimum and a Landammann of Switzerland replaced the directorate of the Helvetic Republic. As a direct consequence, the representatives of the cantons resolved to dissolve the central postal administration on September 10, 1803 at the re-introduced assembly in Friborg 1803.

The federal treaty of August 7, 1815 replaced the mediation act of 1803, but the regained cantonal postal sovereignty was retained until the state was founded.

From confederation to state

The Swiss Post was established after the Sonderbund War (1847) in the course of the establishment of the Swiss federal state in 1848, whose constitution came into force on September 12, 1848. The former 17 cantonal postal administrations and a central office were to be merged under the umbrella of the Postal and Building Department (today: DETEC ) under the supervision of the Swiss Federal Council , in accordance with a federal resolution of the Federal Council of 28 November 1848 . With the laws on the postal shelf and postal organization of June 4, 1849, the Swiss Post took shape. The takeover by the federal government was set for January 1, 1849, but did not take place until October 1, 1849 when the uniform tariff law came into force. Benedikt La Roche Stehelin from Basel held the position of General Director of the Swiss Post . The political supervision lay with the St. Gallen Federal Councilor Wilhelm Matthias Naeff . From the 18 federal postal districts, eleven emerged at that time. This division existed until 1911 and was only slightly changed by the change of the canton of Zug from the Zurich postal district to the Lucerne postal district . The district post offices replaced the cantonal post offices. One year after the organization was set up, the total workforce was 2,803.

With the first revision of the Federal Constitution on May 29, 1874, the Federal Assembly exempted the Confederation from the obligation to pay the cantons financial postage compensation. In addition, Art. 36 in the constitution was supplemented with regard to the telegraph system. From then on, not only the post, but also the telegraph system in the Confederation was a purely federal matter. The proceeds of the "Post and Telegraph Administration" flowed into the federal treasury.

The Universal Postal Union was founded in 1874, with Switzerland as a founding member.

Development of loose telephone networks

The German Reich was a pioneer in the field of telephony. The Swiss Telegraph Directorate, taking the Reich as its model, ordered the first telephone sets from Siemens & Halske in 1877. In December 1877 trial operations took place between Bern, Thun and Interlaken and in Bellinzona . Despite a request, the Telegraph Directorate has not yet issued private concessions, but in return allowed the cantonal interior department of the Canton of Vaud to connect the psychiatric clinic in Cery by telephone . In 1878, the Swiss Federal Council placed the telephone system under the telegraph monopoly. This state monopoly of the Telegraph Directorate was not without controversy. Telephone entrepreneur Wilhelm Ehrenberg, for example, lodged a complaint with the Swiss Federal Assembly. The federal councilors nevertheless stuck to the expanded mail shelf.

The International Bell Telephone Company was initially in discussion for setting up the network . Wilhelm Ehrenberg, in turn, applied for the construction of a central telephone station in Zurich for the company Kuhn & Ehrenberg , which made a name for itself with the telephone transmission of the Federal Singing Festival in Zurich via a line to Basel . The "Central Telephone Station in Zurich" officially went into operation on October 2, 1880. The private Zurich telephone company remained an episode. In 1886 the federal government took over the Zurich network. In the other Swiss cities, the telegraph directorate was responsible for setting up the telephone network. The postal and railway department of Federal Councilor Simeon Bavier granted permission for this in 1880. The number of subscribers was decisive for the structure. “While the Telegraph Directorate in Basel was looking for participants itself”, in the other cities the private trade, industrial and banking associations helped in their own interest to find subscribers. So, first in the cities, then in larger communities, loose telephone networks emerged that were only gradually connected to one another.

First World War

Swiss postal traffic with foreign countries was severely restricted by the outbreak of war in 1914. In particular, deliveries overseas could not be guaranteed, as the shipments fell victim to the submarine war several times . When Italy entered the war in 1915, the situation worsened. Neutral Switzerland took over the delivery of interned mail during the First World War. After the end of the war in 1918, Switzerland was partially reimbursed for the additional financial expenses incurred in this way.

Interestingly, on November 8, 1918, in the run-up to the state strike , telephone calls between Robert Grimm and Ernst Nobs and Rosa Bloch (see source) were tapped. The PTT attempted to break the connection between the local strike committees and the general strike leadership by censoring telegrams and telephones. The Ticino example, remained isolated communicative during the strike. In March 1919 the state strike process against 21 members of the strike leadership took place.

Between the wars and the establishment of the PTT

The interwar period brought major challenges for Swiss Post. The global economic crisis at the beginning of the 1930s led to a decline in postal traffic, whereupon the Directorate General took rationalization measures, which among other things led to a reduction in staff. From 1920 the first steps were taken to organize the postal system with the telephone and telegraph systems. In 1928 Reinhold Furrer was appointed the first general director of the newly founded Swiss Post, Telephone and Telegraph Company (PTT) .

In 1939 it was decided by the general management of the PTT that postal yellow should be used for all purposes. The color had already been introduced in 1849, but for a long time the letter boxes were painted dark green and the post office signs were painted red and white.

Second World War

The outbreak of war in Europe in the first days of September 1939 also had far-reaching consequences on very different levels for the Swiss Post, which was networked across Europe. First of all, for the PTT, the war meant a decline in the domestic and international civilian mail delivery. However, the statistics indicate longer-term trends. Letters and parcels as well as newspaper traffic to Germany , but also to the other neighboring countries, slowly declined as early as the 1930s. The takeover of power by the National Socialists in Germany had an inhibiting influence on newspaper traffic, which was increasingly subject to censorship . Given the decline in letter post, it can be assumed that the competition of the emerging telegram partially displaced letter post. In contrast to the downward trend of regular mail numerically exploded the area of the field post . The handling of interned mail and prisoner of war mail were added during the Second World War .

The workforce in the administration rose continuously during the war years (see diagram). The proportion of women during this period was an average of 26.2%, although it fell from 30.8% (1944) to 27.9% (1945) at the end of the war. Only between the years 1939 and 1941 did the total workforce of the PTT decrease from 21,809 over 21,252 to 21,216 people. At the end of 1945, the PTT confirmed 23,171 people compared to 21,809 in 1939. In these years, for every 100 employees, there were an average of 18 women (17.7%). Female employees continued the Swiss postal majority than non-civil servants telephonist one.

Postal traffic with Germany

Post traffic with Germany remained largely unaffected during World War II. However, the fact that German post officials were still allowed to move freely into the city of Basel caused discussion. In 1939, the PTT had decided to allow the German Reichspostwagen to continue to the post office Basel 17 Transit , which was located in the SBB station: on the one hand because of the more efficient handling, on the other hand because of the national security. The PTT feared a change in the practice and thus an exchange of mail at the border, which meant additional work and a traffic obstruction. In addition, for reasons of national security, they did not want to offend the German side.

The war led to extended transmission and delivery times. Due to the German and French censorship authorities, there were also delays in the Swiss postal service. The war thus had a major impact on Swiss postal traffic with other countries.

POW mail

The PTT played a central role in international mail during World War II. Since Switzerland remained officially neutral in World War II while the neighboring countries were at war, its location was predestined to take over the mediation of prisoner- of- war mail. Those responsible assumed a positional war in the west and did not expect many prisoners. They therefore assumed that arranging prisoner-of-war mail - in contrast to the First World War - would only involve little effort.

They even advocated proactively conveying prisoner-of-war mail. That means that the PTT approached the warring countries and offered themselves as mediators. This enabled the PTT to assign politically isolated Switzerland a role on the international stage. The role of mediator also strengthened national security and neutrality. A financial motivation for the PTT can be ruled out, as prisoner of war consignments are exempt from all taxes according to the Universal Postal Treaty of 1940. As a transit country for prisoner-of-war mail, Switzerland only received a small payment.

On October 24, 1939, the first shipment of prisoner-of-war mail from Germany to the south of France arrived in Basel 17 Transit . There were 200 postcards from French prisoners of war who wrote on preprinted cards that they had been captured and that they were fine.

From December 1, 1939, a car with German prisoner-of-war mail from France rolled via Basel 17 Transit to Frankfurt every day . In the opposite direction, the mail from French prisoners of war was handed over by the Deutsche Reichspost to the Basel 17 Transit post office, where it was reloaded by the PTT and forwarded via Geneva to France. From 1940 the PTT also brokered postal traffic between Germany and Great Britain and its colonies. In order to avoid the chaos of war, detours were accepted. The prisoner of war mail between Germany and Great Britain was partly handled via Spain (Gibraltar) .

The mediation of prisoner-of-war mail was associated with a number of difficulties. Rail traffic was partially interrupted, and as the war went on, there was a lack of transportation, especially rolling stock. Towards the end of the war, the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) refused to provide rolling stock for mail transport to Germany. The German side did not send the wagons back, which meant that over 1,000 Swiss wagons were lost in Germany.

The international postal network was so affected by the war that smooth postal traffic was no longer possible. This had negative consequences, especially for mail with perishable content. The general management of the PTT stated in June 1940 with regard to prisoner-of-war parcels that because of the interrupted mail connections, some “consignments that had been on the way for weeks were showing signs of rot and spoilage”. Some of the food therefore had to be disposed of. This particularly affected the border transit points in Basel 17 and Geneva 2 . In the first third of 1942, a total of 153 rail wagons filled with prisoner-of-war parcel mail were dispatched from Basel 17 to Germany. This number gives an idea of the amount of spoiled food that had to be destroyed due to a lack of delivery options. In times of food rationing, such waste was badly received by the population. In 1945, the Basel 17 post office was heavily criticized in a letter to the editor of the newspaper Die Nation , because the perishable food was not distributed to the Swiss population. At that time there were so many prisoner-of-war packages that the said post office had to store some of the shipments on the platforms because all the storage rooms were already overcrowded. In cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross , perishable food could finally be recycled. Some of the parcels were also sent back to the countries of origin.

post war period

In the meantime, the PTT was also responsible for the state radio and television broadcasts in Switzerland and, after the SRG was founded in 1931, for the maintenance of the SRG studios until the end of the 1980s.

The PTT replaced the last hand-operated switchboard in Switzerland on December 3, 1959.

On October 1, 1964, the four- digit postal code system that is common in Switzerland today was introduced to simplify sorting. Now there was no longer any need for staff with very extensive knowledge of the geography of Switzerland. These postcodes were ultimately the basis for the automatic sorting of letters and parcels.

In 1978, before the first ATM of postomat introduced.

The PTT reform introduced cost transparency in 1990, ended cross-subsidization and in 1993 split PTT into Post PTT and Telecom PTT.

On February 1, 1991, PTT introduced express, A and B mail . The price of an A post stamp was now 80 cents instead of 50 cents for the B post. In order to mark the letter as A Mail, an A had to be added next to the stamp.

In 1995 the so-called "PubliCar" was introduced. This is a kind of post bus, but it can be ordered by calling.

In 1996 "Swisspost International" was founded. This is and was an offshoot of the PTT abroad. The core business is the dispatch and delivery of documents and goods in cross-border traffic abroad.

Shortly before its dissolution in 1998, the PTT was the largest employer in Switzerland.

In the course of the European liberalization of telecommunications , the PTT were dissolved on January 1, 1998 and their tasks were transferred to the Swiss Post and Swisscom .

Organizational structure of the PTT

| History of the central administration of the postal, telegraph and telephone companies | |

|---|---|

| 1849 | General Postal Directorate |

| 1879 | Oberpostdirektion |

| 1927 | Federal Post and Telegraph Administration |

| 1928 | General Directorate PTT |

| 1935 | Swiss Post and Telegraph Administration |

| 1936 | Swiss Post, Telegraph and Telephone Administration (PTT) |

| 1960 | Swiss Post, Telephone and Telegraph Companies (PTT) |

| 1993 | The Post / La Poste / La Posta PTT |

| 1998 | Die Post / La Poste / La Posta (Swiss Post) |

|

Source: PTT archive

|

|

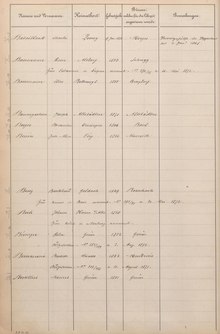

General Management (PTT)

On January 9, 1849, the Federal Council appointed Benedikt La Roche-Stehelin from Basel as the first General Post Director . In July of the same year, La Roche-Stehelin resigned due to differences of opinion with the head of the Post and Building Department, Federal Councilor Naeff . There were differences in the number of civil servants and the level of pay within the central administration. The position remained vacant until January 1, 1879 and was filled by the head of the postal department .

It was not until the federal law of August 21, 1878 that the federal councils created financial incentives to fill the top civil servant, who was now called the Chief Postal Director. As of January 1, 1879, the General Directorate of the Post became the Oberpostdirektion . The new Postal Act of 1910 only slightly expanded the powers of the Oberpostdirektion, but regulated the organization of the central administration. In August 1920 the Oberpostdirektion took over the administration of the telegraph. When the PTT was founded in 1928, the name of the central administration also changed from Oberpostdirektion to Generaldirekton PTT . The Federal Assembly expanded its responsibilities twice: in October 1930 and in March 1946. Neither the Federal Council nor the Federal Assembly was responsible for general management (fees, postal concessions, salaries, etc.), which was now the sole responsibility of the General Management.

In 1961 a new PTT Organization Act came into force. The now three-person postal administration, instead of a single general director, was divided into the internal departments of post , telecommunications and the presidential department . In 1970 she received a board of directors with authority over the PTT administration.

TT directorate

| Administrative names of the telegraph and telephone companies | |

|---|---|

| 1852 | Federal Telegraph Administration; Telegraph inspection groups |

| 1854 | Federal Telegraph Directorate |

| 1880 | Federal Telegraph and Telephone Administration |

| 1909 | Federal Upper Telegraph Directorate |

| 1927 | Federal Post and Telegraph Administration |

| 1935 | Swiss Post and Telegraph Administration |

| 1936 | Swiss Post, Telegraph and Telephone Administration (PTT) |

| 1938 | Telephone Directorate; District Telephone Directorates (KTD) |

| 1960 | Swiss Post, Telephone and Telegraph Companies (PTT) |

| 1983 | Telecommunication circuit directorates (FKD) |

| 1993 | The Post / La Poste / La Posta PTT |

| 1994 | Telecommunications Directorates (FD) / Telecommunications Directorates (TD) |

| 1997 | Swisscom AG |

|

Source: PTT archive

|

|

The Swiss telegraph administration actually existed since 1854, after the Federal Council passed a corresponding law. In 1883, the telegraph administration was also given the task of managing the newly emerging telephone system. In 1928 the telephone and telegraph administration finally became part of the PTT, so that the TT management was now subordinate to the general director of the PTT.

In 1961 the general management was restructured and from now on consisted of a director each for postal and telecommunications as well as a head of the presidential department.

post Office

District Post Offices

The postal area of Switzerland was divided into so-called postal districts as early as 1849. At the time, the Federal Council suggested creating eleven such postal districts, but there was opposition, as the number of MPs seemed too high for many. Others were in favor of operating a postal district per canton, as this would have allowed the cantonal posts from before 1848 to be continued. Nevertheless, the proposal to establish eleven postal districts was finally able to prevail.

| Eleven postal districts in Switzerland from 1849 | |

|---|---|

|

|

The postal districts remained as it was, apart from minor border shifts, although there were always voices in favor of tighter administration and accordingly only five or six postal districts in favor.

The postal districts each received a director whose main task was to inspect his post offices and guarantee that the operation was meeting expectations. Often, however, the district post directors had too little time and too few staff to carry out regular inspections.

Post offices

With the establishment of the Federal Post Office in 1849, the post offices were also set up to handle operations. The post offices at the headquarters of the district post office were called main post offices and, due to their size, were divided into subdivisions.

From 1870 the bureaux were divided into three classes. The 1st class post offices were the large post offices and the 2nd class post offices were those that had at least two officials. Finally, the 3rd class post offices were the small offices that were only run by a post holder.

| Number of post offices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | number | |||

| 1970 | 4100 | |||

| 1975 | 3972 | |||

| 1980 | 3917 | |||

| 1985 | 3880 | |||

| 1990 | 3830 | |||

| 1995 | 3646 | |||

| 1996 | 3530 | |||

| 1997 | 3646 | |||

Basel 16 Badischer Bahnhof

The post office Basel 16 Badischer Bahnhof is a specialty among the 1,464 branches (as of 2015): It is located on the grounds of the Badischer Bahnhof and therefore on German customs territory. In the contract of 1852 between Switzerland and the Grand Duchy of Baden , which regulated the construction of the Badischer Bahnhof on Swiss soil, a Swiss post office was also planned within the station premises. It was opened in 1862 with the name "Basel Badischer Bahnhof". From 1913 this post office took over the German internal reloading service of the Bahnpost "against compensation", whereby the exact conditions are not known.

In the 1933 contract, the shared use of the infrastructure of the Badischer Bahnhof was regulated. It was about the so-called baggage and express goods tunnels, which connected the tracks underground and thus accelerated the loading of mail. Said systems were leased equally by the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft to the PTT and to the Deutsche Reichspost , whereby the respective rental share was proportional to the usage. In the 1935 agreement between the Reich Ministry of Post and the PTT, the “compensation for services in the interests of the German postal service”, in particular for the “procurement of the domestic German postal service”, was renegotiated and determined. The Deutsche Reichspost paid the PTT the wages of seven workers, which resulted in an annual amount of CHF 35,000.

Between 1914 and 1919, the post office was closed due to the First World War and the ensuing occupation of the Badischer Bahnhof by Swiss troops. The post office continued to operate during the Second World War. However, the Swiss mailboxes that were on the platforms were removed in 1940 due to "foreign exchange policy reasons", presumably to prevent Swiss francs from being sent abroad.

The post office is operated today under the name "4016 Basel Bad. Bahnhof".

Basel 17 transit

The Post Office Basel 17 Transit mediates the items arriving and leaving via Basel for international traffic.

Since 1878 there has been a transport post office in the immediate vicinity of the Badischer Bahnhof, which was responsible for handling postal traffic with the Deutsche Reichspost. Around the same time, what was then the Centralbahnhof took over the exchange of pieces with France, Belgium, Great Britain and Alsace. A parcel transit office was created for this task in 1907. The transport transit office had a total traffic of nearly 3.5 million items in 1912. This traffic volume was too big for the old rooms in the Badischer Bahnhof. Therefore, from 1911 to 1913, a new building was built in Basel SBB station, which is an island within the station. Seven separate sidings led to the new post office building.

On September 13, 1913, the transit office at Badischer Bahnhof was merged with the parcel transit office at Basel SBB station. The new post office Basel 17 Transit was given its own building with separate sidings in the Basel SBB train station and included a post office and customs office. There was close cooperation with the Deutsche Reichspost. Both sides agreed on a joint office within the Basel 17 Transit post office. In this, the PTT took over the administration for the services of both countries and carried out work that was exclusively in the interests of the Deutsche Reichspost. The Reichspost only operated a small accounting office. This enabled Swiss Post to cross the border more efficiently as it only had to pass through one post office.

This close cooperation was continued during the Second World War. Nevertheless, the German Reich also radiated a threat. Because they did not want to offend the German side in favor of national security, the PTT decided in 1939 to allow the German Reichspostwagen to continue to transit to Basel. Much of the international mail traffic during the Second World War passed through the Basel Transit post office. Letters and parcels as well as newspaper traffic between Switzerland and Germany were handled entirely through this post office. The prisoner-of-war mail, which the PTT helped to organize after the outbreak of war, passed through Basel Transit. The prisoner-of-war mail passed through Switzerland as a transit country, which meant that this locked mail did not have to be checked by the Swiss customs or censorship authorities. After the outbreak of war, the post office was overcrowded as the postal service collapsed. Therefore, unlike other post offices that suffered from labor shortages due to mobilization , workers were given vacations. The changeover to the war timetables initially resulted in delays in postal traffic to Germany. There were also delays due to the German and French censorship authorities .

After the German occupation of France in June 1942, French postal traffic was handled as a result of controls by German authorities via Basel 17 Transit. The post office is operated today under the name "4017 Basel 17 Transit".

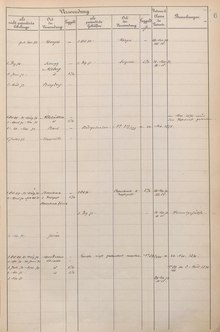

Recruitment and career model of the staff at PTT

The beginnings 1848–1910

The staff body of the postal administration continued after the establishment of the post and Building Department of officers together and employees. The officials dealt with all the office work, the cash and accounting, etc. in the company ... In the administrative company officials dealt with written work, while the employees did manual work, for example as a postman . There was no prescribed model career path in the form of regulations like in Germany or France for civil servants de jure . The workers required were chosen as civil servants on the basis of their previous knowledge and, if necessary, an examination. Until 1868 the civil servants were recruited from private assistants and outside candidates who did not actually have to complete an apprenticeship. In the long run, this recruiting system was not sufficient, so that the administration of the postal department was forced to carry out a new regulation of the selection of postal officials. With the ordinance of the Federal Council of April 1869, the employment of postal teaching staff was regulated by law for the first time. Thus, in order to attract better workers, only candidates who had initially proven themselves in an apprenticeship were selected, and the first basis for a PTT career model was created.

The postal department determined the number of teaching staff to be accepted each year (from 1873 the General Postal Directorate was responsible for recruiting). The posts were advertised by the district post offices . Both women and men were admitted in the same way, depending on the position. The minimum age of applicants should not be under 16 and the maximum age not over 25 years (in 1873 the maximum age was set at 30). Before the applicants were called to an examination, the district post offices had to inquire as detailed as possible about each individual.

Entrance exam and apprenticeship period

The test covered general education, handwriting, numeracy, knowledge of political geography and national languages. It took place in the presence of the district post director and an official of the general post office (from 1873 onwards of two officials of the general post office and the district post director or his deputy). With the ordinance of March 1895, applicants from the upper classes of a middle school (grammar school, canton school or technical college) with a passed school leaving certificate no longer had to take an entrance examination. During the apprenticeship, which usually lasted one year (from 1873 it lasted 18 months and from 1913 two years), the teaching staff was introduced practically and theoretically to all branches of service. During the apprenticeship, the teaching staff was given the opportunity to supplement their general education and attend language courses. The apprenticeship was concluded with a patent examination. Depending on the result, the candidate received a first, second or third class patent (very satisfactory, satisfactory and mediocre) and became aspirants from then on , although access to the patent examination was also open to other people under certain conditions.

Until the firm election, the holders of patent I or II class were used as temporary assistants. For those seeking patent III. There was no guarantee that they would be elected as civil servants. The young people were able to apply for advertised post office workers and were then elected to post office workers . This created the first basis for career planning. For administrators test applicants were only admitted who worked at least 12 years in operational service and could have impeccable performance and behavior. The applicants had to prove, orally and in writing, that they had a good general education (mother tongue and foreign languages, civics and Swiss history, general literature, economics and law, current issues of a social, economic and cultural nature) and thorough specialist knowledge. After passing the exam, the final election of a candidate in the administrative service must be preceded by a trial period of at least six months. Not included in the general selection process were the few special civil servants with a higher level of specialist training, i.e. lawyers , economists , architects , engineers , technicians , etc. as they were initially only employed by the General Management. These officials were selected directly by the Head of Department or the Director General.

So far, technically or academically trained personnel have not been considered for filling the middle and higher management positions of the district administration service. It may come as no surprise, then, that an overwhelming majority of middle and senior officials in the district administration service between 1849 and 1949 had previously completed a postal apprenticeship. The following table gives an overview of the distribution of civil servant posts within the Directorate General (Central Administration), the district post offices and other civil servants:

| year | General Directorate | District Directorate | business | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | in % | number | in % | number | in % | Total | |

| 1850 | 18th | 0.6 | 37 | 1.3 | 2748 | 98.1 | 2803 |

| 1890 | 50 | 0.7 | 213 | 3 | 6815 | 96.3 | 7078 |

| 1910 | 130 | 1 | 423 | 3.2 | 12730 | 95.8 | 13283 |

| 1947 | 618 | 3 | 420 | 2 | 19641 | 95 | 20679 |

Reforms of the recruitment process from 1910

The recruitment process, which was last adapted in 1873, showed more and more shortcomings over time. The training of the candidates was unsatisfactory, since very few office managers took care of the teaching staff properly and tried to guide them methodically. The young people were mostly dependent on themselves. The civil servants' association finally gave the impetus for radical change by calling for the teaching to be redesigned. However, the association of civil servants only found a hearing with its petition of February 1910, addressed to the Oberpostdirektion, which included the following reform proposals, among other things: raising the entry age, extending the entrance examination, involving educational experts on the examination committee, extending the apprenticeship period, creating introductory and final courses, Careful selection of teaching offices, obligation of teaching staff to attend advanced training schools and extended specialist examinations.

In the postal regulations of November 1910 and its implementation provisions, some of the suggestions made by the Association of Officials were taken into account. The minimum age of applicants has been increased to 17 years. Only male applicants who had attended secondary school for two years were admitted to the entrance examination (the decision was made in 1894 to no longer admit women to graduate postal apprenticeships). The Oberpostdirektion was authorized to call in pedagogues as examination experts. More attention was paid to training during the apprenticeship. The newly established curriculum consisted of a practical and a theoretical part. It was the duty of the office manager to guide the apprentice appropriately and also to monitor him outside of work. Introductory courses were only provided in case there was a need for something, but a two-week closing course was arranged. The county post offices were responsible for attending advanced training schools for teaching staff. The duration of the apprenticeship remained unchanged at 18 months after the reform. When the number of applicants registered fell noticeably between 1910 and 1912, the minimum age was again reduced to 16 years and the requirement for secondary education was waived in order not to close the doors to the administration to applicants from less wealthy groups.

The selection of the candidates was made dependent not only on the test result, but also on the information that was obtained about them. The family relationships, the way of life and the reputation of the candidate and his parents were relevant aspects. The mental and moral suitability of the applicant also played a role that should not be underestimated. Finally, the candidates had to be examined by the medical officer of the postal administration. The medical examiner's certificate was examined by the senior physician of the general federal administration and he assessed whether a candidate should be considered suitable from a medical point of view for employment in the federal service.

Introductory and final courses for PTT teachers

In 1929 an introductory course for PTT teaching staff was carried out in Winterthur in a first pilot test. The feedback and the positive experience gained from the first introductory course led to the establishment of mandatory introductory courses for all PTT teaching staff throughout Switzerland. The introductory course preceded the actual apprenticeship and lasted three weeks. During the apprenticeship, the teaching staff was given the opportunity to attend a one-week theoretical course at the headquarters of the district post office. A few weeks before the end of the apprenticeship, a final three-week course took place, in which a number of civil servants from administration and business participated as instructors. The apprenticeship was followed by the aspirant period, which at the end of 1947 had been reduced from 20 months to 12 months. During the aspirant period, the prospective civil servants were transferred here and there for further practical training, in the city and in the country, but above all, and for a longer period of time, in a foreign language area. Incidentally, after the specialist examination, it was up to each individual how they wanted to continue their education, in general and professionally.

The 1960s through the early 1990s

Up until and after 1960, the careers of PTT officials were also adjusted through several reforms. The civil servants' careers were regulated under C15. The entry, transfer and promotion conditions within the PTT administration played an important role here. The careers were linked to those of the federal administration and the other federal companies. The term monopoly occupation was first mentioned in 1967 in the personnel regulations C2, which regulated the training of PTT learning staff. The PTT trained in five monopoly professions: secretary teaching staff (future cadre), operating assistant teaching staff (counter staff), uniformed operations teaching staff (postman), telephone teaching staff and telegraph teaching staff.

| The operating staff | The employees in the company completed a monopoly apprenticeship (that is, an apprenticeship that can be carried out for a job at Swiss Post). In addition to the so-called “monopoly lists”, semi-skilled personnel and temporary workers also worked in the company. The postal service knew three broad categories of employees. |

|---|---|

| The certified officials | After completing their apprenticeship as company secretary, the qualified civil servants worked at the counter, in the dispatch and rail mail service and in operational management functions. Until 1972 women were not admitted. |

| The operations assistants | The assistants operated the counter and worked in the back office, and it was mainly women who worked in this job. The first men did not join them until 1972. |

| The uniformed officers | The uniformed officers worked as postmen, in processing letters and parcels, or took on manual office work. Until 1973 the profession was reserved for men. Her uniform showed her to be a PTT employee. A promotion to lower management positions was possible. |

| The administrative staff | As in the first half of the 20th century, administrative staff included anyone who worked for the general management or in a district post office. In contrast to the first half of the 20th century, a qualified civil servant could not transfer to the career of senior administrative staff after an internal examination after seven years in the postal service (including apprenticeship) at the earliest. Similar to the administrative official examination from 1930 onwards, general knowledge of economics and business administration, history and political science and mother tongue and foreign language skills were tested. After passing the exam, the officials occupied almost all higher positions in the district post offices and many in the general office. |

|---|

Career model of a post office secretary in the second half of the 20th century

| 1. Previous school education | Traffic school, business school, middle school (at least 2 years), high school diploma, teacher certificate, commercial apprenticeship would be ideal |

| 2. Assessment of suitability | Depending on the school, only an aptitude test or an entrance examination |

| 3. Training (2-3 years) | Training time in a suitable post office or teaching post office |

| 4. Specialization phase (4-6 years) | Stay in French-speaking countries, dispatch / rail mail service, travel service, postal check service, counter service, airport post offices / customs post offices |

| 5. Preparation phase for management position | Deployment in junior management as course instructor, works supervisor, deputy company cadre, post office holder replacement |

| 6. Management function | Management function in the company as office manager, post office owner, service manager, office manager (administrator) or administrative tasks at a district directorate or the general directorate |

Permeability

For a long time, the permeability between the federal administration and the private sector rarely occurred. Due to the measures taken by the federal government, the federal administration tied the civil servants to itself in the long term and through specifically tailored training such as the monopoly occupations, the qualifications of the PTT company were not recognized in the private sector for a long time. Someone who had previously completed a postal apprenticeship eventually became the head of a department within the PTT. In contrast, the permeability of civil servants within the federal administration (from one department to another) was somewhat more frequent. For example, some PTT apprentices have switched to the diplomatic service, as Charles Redard's career shows.

It was only after the liberalization efforts of the 1990s that more and more degrees were gradually recognized in the private sector in order to promote permeability between the federal staff and the private sector.

Professional categories within the PTT

The civil servant status

Until the end of the First World War, the employment conditions for federal personnel were regulated relatively incompletely. In 1918 the first steps were taken to develop binding, holistic standards. After years of negotiation, the federal law on the employment relationship of federal civil servants came into effect on January 1, 1928. The civil servant status was clearly defined therein. Officials were only those who were elected by the Federal Council, a subordinate office or a federal court for a three-year term of office. The federal administration had to advertise the vacant civil servant positions. Only Swiss citizens with an impeccable reputation were eligible to fill the positions . The election as a civil servant could also be made dependent on further conditions, for example on a certain number of years of service. In 2002 the civil servant status was officially abolished in Switzerland.

Postman

To become a postman , interested parties had to apply directly to one of the eleven district post offices in the 1950s. Applicants should generally be between 18 and 23 years old. Foreign language skills were only required in postal circles through which a language border ran. Depending on the postal district, physical requirements were also placed on the applicants. For example, the postmen in mountain regions had to be in good health, since work in winter and in bad weather meant considerable physical strain. The highest-ranking uniformed officials among the postmen were the company assistants who mainly carried out activities in the diversion points. Since 1963, women have also been officially admitted as postmen.

The postal worker

The postal assistant was primarily responsible for the counter and office work. From the middle of the 20th century, 18 to 22-year-olds could begin a twelve-month apprenticeship. Another requirement was a degree from commercial or secondary school . Most of the work was done by female employees. The private post office assistants worked in smaller rural post offices and were employed by a post office owner, with whom they completed a year-long apprenticeship. This was followed by another year of training at another post office.

The post driver

Until the first attempts with buses in 1906, the PTT used horse-drawn carriages to transport travelers across Switzerland. The Postbus was only able to establish itself definitively in the interwar period. In the 1950s, the PTT had 400 post chauffeurs whose main task was to drive the Postbuses used for passenger traffic. Applicants between the ages of 22 and 28 who reached a minimum height of 165 cm and were considered to be suitable for the military were admitted. The chauffeur was also responsible for the maintenance of the vehicle. Above all, trained auto mechanics and vehicle fitters were suitable for the profession of post chauffeur. It was also assumed that the drivers had already had at least one year of experience in driving heavy trucks. After passing the exam, there was a one-year trial period. After another two years and a subsequent examination, the chauffeur rose to become a driver-mechanic. There was also the opportunity to train as a garage manager or foreman.

Special order in Berlin during World War II

During the Second World War, Switzerland represented the interests of various states as a diplomatic protective power . PTT officers worked as (post) car drivers, chauffeurs and mechanics for the automobile service of the Swiss legation, department for protecting power matters in Germany .

Due to the increased need for vehicles and skilled operating personnel, the department for foreign interests in Bern hired additional (post) drivers, chauffeurs and mechanics as a result of the increase in protective power mandates taken over by Switzerland . The general management of the PTT in Bern dispatched several people who took up their new positions in the automobile service of the Swiss delegation in Berlin between February 1944 and January 1945. At the beginning of February 1945, 12 people worked for the automobile service in the embassy alone.

A mention of the automotive service in the specialist literature is rare. Paul Widmer describes it implicitly: "The much larger staff of the protecting power department moved into accommodations that were 50 to 100 kilometers outside of Berlin . Uniformed PTT chauffeurs who were doing their active military service on German soil, so to speak, drove the embassy staff back and forth. They also stood available to the personnel of the protecting power department, who were billeted in Wutike , Blumenow , Bantikow and in five other villages in the Margraviate of Brandenburg . "

The main task of the automobile service was to ensure contact between the offices of the Swiss representations in Germany. As the war continued, he proved to be indispensable in this area, especially since the telephone connections were frequently out of order as a result of day and night attacks by Allied bomber groups . In addition, the automobile service ensured the supply of food and spare parts, which were difficult to obtain as a result of the German war economy. In his activity report of November 20, 1945, the head of the garage of the automobile service exemplarily explained how those responsible for the automobile service avoided the lack of spare parts by collecting light metal remnants from shot down " Flying Fortresses " (B-17). To a greater extent, the service took over the transport of Swiss employees for business and vacation trips between Bern and Berlin, as the direct train connection between Switzerland and Germany was interrupted more frequently in the winter months of 1944 and 1945 after the railway infrastructure was bombed.

The monthly camp inspections of the interned civilians of the warring states with Germany, the diplomatic personnel held and the prisoners of war by representatives of the Swiss delegation belonged to the extended area of responsibility of the department for protecting power matters . The German Foreign Ministry forbade the Swiss embassy staff to inspect the concentration camps, citing "domestic affairs" that were outside the scope of the 1929 Geneva POWs . Despite the beginning of the offensive on Berlin by the Red Army , the Swiss delegation continued to drive to the internees in February and March 1945 in increasing numbers (until the end of the war). In these two months, the chauffeurs of the automobile service covered the greatest mileage with 40,174 km and 41,659 km respectively with a monthly average of approx. 22,555 km.

The intensification of the war around Berlin led in the spring of 1945 to the evacuation of the automobile service from Herzberg via Grosswudicke (north-west of Berlin) to Kißlegg in Upper Swabia. The last move from Kisslegg to Bad Homburg near Frankfurt am Main followed in October 1945 .

After Germany's unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, the Swiss department for protecting power affairs in Germany and the associated automobile service of the Swiss legation dissolved.

The telegraph operator

The main task of the telegraph operator was the transmission of telegrams. The correspondence was mostly written with code words. Distributing, booking and billing the telegrams were also part of the tasks. Due to the rapidly increasing telephone traffic from the end of the First World War, the telegraph slowly lost its importance, which meant that fewer telegraph operators were needed. Knowledge of different languages was a prerequisite for practicing the profession. In addition, the telegraph operator also had to be able to correct technical problems. In the 1950s, after five years, which included the apprenticeship, he was able to transfer to the administrative service of the telephone management. The post offices and banks were connected to the telegraph office by pneumatic tube systems. There, various stations used signal lamps to indicate the arrival of shipments. In addition, from the late 1930s onwards, teleprinters were used that looked like a typewriter. With these teleprinters, the telegraph operators no longer had to write messages in Morse code , but could use letters directly. The type of transmission of the telegram was selected by the recipient. It could be delivered over the phone, by pneumatic tube, by stub, or by telex.

The operator

The operator's main task was to manually set up the telephone connections in the switchboards before telephony was automated across the board from the middle of the 20th century. Since the first Swiss telephone networks went into operation in the 1880s, the telephone directorates have only employed women in the switchboards. There was never a public resolution that would have forbidden men to work in the operator service, but the telephone administration was of the opinion that the higher female voices on the phone were easier to understand. Furthermore, the female gender was ascribed more gentleness and patience in dealing with customers. Last but not least, female workers were cheaper at the time, which the TT management took into account in their considerations. Compared to all employees in the telephone and telegraph administration, the telephone operators were at the bottom end of the pay scale. Applicants who were between 17 and 20 years old and who had knowledge of a second official language were admitted to the entrance examination as telephone operators around 1940 . Working in the switchboards was very demanding. The workers had to work quickly in a noisy environment and were monitored by a supervisor. They always had to be friendly and courteous towards the telephone subscribers. The operators were also subject to official secrecy . It was strictly forbidden for them to give third parties information about phone calls they had made. Failure to observe telephone secrecy resulted in dismissal in lighter cases, while serious violations were punished with prison sentences.

Workforce

| year | PTT | of which post | of which Telecom |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | approx. 30,000 | ... | ... |

| 1970 | 47,433 | ... | ... |

| 1975 | 50,791 | ... | ... |

| 1980 | 51,592 | ... | ... |

| 1985 | 56,991 | ... | ... |

| 1990 | 63,654 | ... | ... |

| 1995 | 59,635 | 38,524 | 20,143 |

| 1996 | 59,661 | 38.008 | 21,204 |

| 1997 | 58,431 | 36,880 | 21,457 |

| Swell: | |||

economy

sales

| year | amount | |

|---|---|---|

| 1938 | 147 million | |

| 1948 | 267 million | |

| Source: | ||

Transport services

| year | Addressed mail | Shipments without an address | Newspapers | Packages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 1756 | 257 | 1113 | 128 |

| 1975 | 1821 | 227 | 1042 | 132 |

| 1980 | 2067 | 487 | 1138 | 150 |

| 1985 | 2458 | 620 | 1165 | 186 |

| 1990 | 2998 | 789 | 1200 | 224 |

| 1995 | 3160 | 970 | 1137 | 199 |

| 1996 | 3196¹ | 1048 | 1106 | 159¹ |

| 1997 | 3231 | 1165 | 1070 | 153 |

| ¹ = From 1996 there were new criteria for the delivery of letters and parcels. | ||||

| All numbers are multiplied by 10,000! | ||||

| Source: | ||||

Telecommunications services

phone

| year | Main connections in 1000 | Mobile phone connections in 1000 | Local calls in millions | Long distance calls, in millions of taxi minutes | International calls in millions of taxi minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 1945 | - | 988 | 3210 | 287 |

| 1975 | 2462 | - | 1080 | 3658 | 506 |

| 1980 | 2839 | 4th | 1209 | 4592 | 885 |

| 1985 | 3277 | 9 | 1408 | 5895 | 1361 |

| 1990 | 3943 | 134 | 1663 | 8556 | 2380 |

| 1995 | 4318 | 447 | 1890 | 8567 | 3199 |

| 1996 | 4547 | 663 | 1898 | 8957 | 3454 |

| 1997 | ... | 1044 | ... | ... | ... |

| Source: | |||||

Teleinformatics

| year | Fax¹ in 1000 | Telex subscriptions in 1000 | Telex traffic in millions of taxi minutes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | - | 13 | 80 |

| 1975 | - | 22nd | 123 |

| 1980 | - | 31 | 173 |

| 1985 | 5 | 39 | 240 |

| 1990 | 83 | 24 | 133 |

| 1995 | 197 | 8th | 47 |

| 1996 | 207 | 7th | 39 |

| 1997 | ... | ... | ... |

| ¹ = Subscriber registered in the PTT fax directory | |||

| Source: | |||

Research and Archives

The files and library holdings of the former PTT companies are managed by the PTT archive . The PTT archive has also been operating an oral history archive since 2014. For this purpose, around 10 to 15 former PTT employees are interviewed each year with the aim of documenting the change in the company.

swell

- Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, reports on the use of PTT drivers in Berlin during World War II , 2017.

See also

literature

- Ernest Bonjour: The History of the Swiss Post . PTT General Directorate, Bern 1949.

- Karl Kronig (Ed.): From the post. 150 years of Swiss Post. Museum for Communication , Bern 1999, ISBN 3-905111-40-3 .

- Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland. Your history through 2000 years . Hallwag-Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 .

- Yvonne Bühlmann, Kathrin Zatti: Women in the Swiss Telegraph and Telephone System, 1870–1914 . Chronos-Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-905278-96-0 .

- Helmut Gold (ed.), Annette Koch (ed.), Rolf Barnekow (contributions): Miss from office. Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7913-1270-7 .

- General Directorate PTT (Ed.): 100 Years of Electrical Communications in Switzerland , 1852–1952, Volume 3. Bern 1962.

- Professions of the PTT. In: Städtische Berufsberatung Zürich (Hrsg.): Educational leaflet for pupils in the 2nd and 3rd secondary grades and the other final grades. No. 29. Zurich 1953, pp. 55–56.

- Oskar Hauser: The telegraph operator. In: Robert Bratschi (Ed.): My service, my pride. Basel 1941, pp. 140-141.

Web links

- Karl Kronig: Post, Telephone and Telegraph Companies (PTT). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Website Museum for Communication in Bern

- PTT archive, Köniz

- Oral History Website of the PTT Archives

- Swiss Society for the Protection of Cultural Property , accessed on October 18, 2012

- Post office chronicle Switzerland 1849 - 2017

- Herbert Stucki, A Lifelong At PTT - The Monopoly Professions

Individual evidence

- ↑ PTT - SRF 10vor10. In: Play SRF. SRG SSR, December 8, 1997, accessed April 25, 2020 .

- ^ Andreas Fankhauser: Helvetic Republic. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . January 27, 2011 , accessed May 30, 2017 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . The Eidgenössische Post, Bern 1949, p. 16 .

- ↑ Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland. Your history through 2000 years . Hallweg Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 113 .

- ^ A b Arthur Wyss: The post office in Switzerland. Your history through 2000 years. Hallweg Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 115

- ↑ Jürg Stüssi-Lauterburg : Stecklikrieg. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . February 20, 2012 , accessed May 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland . Your history through 2000 years. Hallweg Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 118.

- ^ A b Arthur Wyss: The post office in Switzerland. Your history through 2000 years . Hallweg, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 119.

- ^ Andreas Fankhauser: Mediation Act. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . December 8, 2009 , accessed May 30, 2017 .

- ^ A b Arthur Wyss: The post office in Switzerland. Your history through 2000 years. Hallweg Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 211.

- ^ Online official publications BAR: Law on the postal shelves . In: Federal Gazette . tape 2 , no. 30 , 1849, pp. 102-108 .

- ↑ Karl Kronig (Ed.): From the post. 150 years of Swiss Post . Museum for Communication, Bern 1999, p. 8 .

- ↑ General Post Directorate / Oberpostdirektion, 1849-1920. In: Köniz, PTT archive. Retrieved May 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Thomas Schibler: Benedikt La Roche. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . November 13, 2008 , accessed May 31, 2017 .

- ↑ Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland. Your story in 2000 years. Hallweg, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 213.

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949. The Eidgenössische Post, Bern 1949, p. 39, 44 .

- ↑ Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland. Your story in 2000 years. Hallweg Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , pp. 213-214.

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council to the High Federal Assembly on its management in 1850 . In: Federal Gazette . Volume 2, No. 39, 1851, accessed on May 30, 2017, pp. 277–343, here: p. 283.

- ^ A b Arthur Wyss: The post office in Switzerland. Your story in 2000 years. Hallweg Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 215.

- ↑ Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation of May 29, 1874. (PDF) April 20, 1999, p. 26 , accessed on May 30, 2017 .

- ^ Karl Kronig: Post. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . January 20, 2011 , accessed June 1, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Telegraph Directorate / Obertelegraphendirektion / General Directorate PTT Technical Department, 1852-1932. In: Köniz, PTT archive. Retrieved June 1, 2017 .

- ↑ Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland . Hallwag Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 185 .

- ^ Historical Archives of the (Swiss) PTT. Retrieved August 25, 2018 .

- ^ Andreas Thürer: Ticino between victory celebrations and general strike in November 1918 . In: Roman Rossfeld et al (Ed.): The state strike. Switzerland in November 1918 . Baden 2018, p. 349 f .

- ↑ Arthur Wyss: The Post in Switzerland . Hallwag Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-444-10335-2 , p. 185-186 .

- ↑ a b c d e Swiss Post: History of the Post. Retrieved April 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: Yearbook 1945 , pp. 90–92; http://pttarchiv.mfk.ch/detail.aspx?ID=203574

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: year book (1939–1945). Annual report, annual accounts, statistics . Swiss Post, Telegraph and Telephone Administration, Bern (1940–1946), pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-00 C_0040_01 War measures, war timetable, 1939 (dossier).

- ↑ PTT archive, Köniz: P-00 C_0040_01 War Measures, War Roadmap, 1939 .

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Message from the Federal Council to the Federal Assembly on the agreement concluded at the 11th Universal Postal Congress in Buenos Aires. (7 May 1940.). In: Federal Gazette. Volume 1, No. 19, 1940, accessed on May 29, 2017, pp. 457-603, here: SS 460, 484, 534.

- ↑ PTT archive, Köniz: P-00 C_0040_01 War Measures, War Roadmap, 1939 .

- ^ PTT archive, Köniz: Vers-057 A 0009_2, prisoner of war mail Second World War.

- ^ PTT archive, Köniz: P-00 C_0066_01 war measures, war timetable 1940.

- ^ PTT archive, Köniz: Vers-057 A 0009_2, prisoner of war mail Second World War.

- ^ A b c Karl Kronig: Post, telephone and telegraph companies (PTT). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland. October 13, 2011, accessed April 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Swiss National Museum | blog.nationalmuseum.ch: Please connect! The automation of the switchboards. In: Blog on Swiss History - Swiss National Museum. December 3, 2019, accessed on April 29, 2020 (German).

- ^ Introduction of postcodes by the PTT - Play SRF. In: Play SRF. SRG SSR, June 10, 1964, accessed on April 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Introduction of A and B Mail - SRF knowledge. In: Play SRF. SRG SSR, January 31, 1991, accessed on April 29, 2020 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . The Eidgenössische Post, Bern 1949, p. 44-45 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . The Eidgenössische Post, Bern 1949, p. 45 .

- ^ SFA online official publications: Act on the Swiss postal system. (April 5, 1910). In: Federal Gazette . Volume 2, No. 15, 1910, accessed June 4, 2017, pp. 677–720, here: p. 701.

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . The Eidgenössische Post, Bern 1949, p. 40 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . The Eidgenössische Post, Bern 1949, p. 46 .

- ↑ General Directorate PTT, 1980-1997. In: Köniz, PTT archive. Retrieved May 29, 2017 .

- ↑ General Directorate PTT (Ed.): Hundred Years of Electrical Communications in Switzerland, 1852-1952 . tape 3 . Bern 1962, p. 943-944 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . Ed .: The Federal Post. Bern 1949, p. 67-68 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949 . Ed .: The Federal Post. Bern 1949, p. 68-69 .

- ^ Ernest Bonjour: History of the Swiss Post . Ed .: The Federal Post. Bern 1949, p. 77-78 .

- ↑ a b c Federal Statistical Office: Post transport services (PTT) - 1970-1997 | Table. January 30, 1999, accessed April 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Statista: Number of post offices in Switzerland from 2010 to 2016. Accessed on June 19, 2017 .

- ^ Post office chronicle Switzerland 1849 - 2017. Accessed on May 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: Post-199 A 0005 Basel 16 Bad. Railway station.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-00 C_PAA 06105 , international postal contracts .

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-00 C_0143_03, State contracts (1944).

- ^ Post office chronicle Switzerland 1849 - 2017. Accessed on May 30, 2017 .

- ^ Alfred Dietiker: From the post office Basel 17 Transit and its exchange of parcels with other countries . In: Postal Magazine . No. 2 , 1932, p. 56-68 .

- ^ Alfred Dietiker: From the post office Basel 17 Transit and its exchange of parcels with other countries . In: Postal Magazine . No. 2 , 1932, p. 56-68 .

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-00 C_0040_01 War measures, war timetable, 1939 .

- ^ Post office chronicle Switzerland 1849 - 2017. Accessed on May 30, 2017 .

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 81.

- ↑ See report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1869, p. 2f.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 81.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 191.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, pp. 199-200.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, pp. 199-200.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849-1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, pp. 203-204.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 86

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 87.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 202.

- ↑ Herbert Stucki, A lifetime at PTT - The monopoly professions

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 202.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 202.

- ↑ See Ernest Bonjour, History of the Swiss Post. 1849–1949, Volume No. 1, Bern 1948, p. 203.

- ↑ The Swiss Post (ed.), Yellow Moves. Swiss Post from 1960, Bern, 2010, p. 79

- ↑ Herbert Stucki, A lifetime at PTT - The monopoly professions

- ↑ The Swiss Post (ed.), Yellow Moves. Swiss Post from 1960, Bern, 2010, p. 80

- ↑ The Swiss Post (ed.), Yellow Moves. Swiss Post from 1960, Bern, 2010, p. 80

- ↑ The Swiss Post (ed.), Yellow Moves. Swiss Post from 1960, Bern, 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ The Swiss Post (ed.), Yellow Moves. Swiss Post from 1960, Bern, 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ The Swiss Post (ed.), Yellow Moves. Swiss Post from 1960, Bern, 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ See Albert Keller, Training and Further Education in the Monopoly Professions of the PTT, in: Panorama Volume No. 3 of September 1988, pp. 13-17, here p. 15.

- ↑ See. Charles Redard in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland and generally under PTT in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ General Directorate TT (Ed.): 100 Years of Electrical Communications in Switzerland, 1852-1952 . tape 3 . Bern 1962, p. 665-667 .

- ^ Professions of the PTT . In: Städtische Berufsberatung Zürich (Ed.): On the choice of career. Educational leaflet for students in the 2nd and 3rd secondary grades and the other final grades . No. 29 . Zurich 1953, p. 51-52 .

- ↑ The post is here! Postmen and women. Retrieved May 24, 2017 .

- ^ Professions of the PTT . In: Städtische Berufsberatung Zürich (Ed.): On the choice of career. Educational leaflet for students in the 2nd and 3rd secondary grades and the other final grades . No. 29 . Zurich 1953, p. 58-59 .

- ↑ The Postbus: From the Postwagen to the tariff associations. Retrieved May 24, 2017 .

- ^ Professions of the PTT. In: Städtische Berufsberatung Zürich (Ed.): On the choice of career. Educational leaflet for students in the 2nd and 3rd secondary grades and the other final grades . No. 29 . Zurich 1953, p. 52-53 .

- ↑ Collection: Administrative files of the postal, telephone and telegraph companies (today Swiss Post and Swisscom), 1848-1997 . Inventory: PTT publications, 1848-1997 . Regulations, instructions and forms. Dossier: Reports on the use of PTT drivers in Berlin during World War II . Activity report of the automobile service from 1.3.44 to 31.10.45 . Köniz, PTT archive . 2017 . Signature: P-507 . Link , p. 1.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , p. 8.

- ^ Paul Widmer: The Swiss Legation in Berlin. History of a difficult diplomatic post . Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85823-683-7 , p. 265 .

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , p. 5.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , p. 1.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , p. 2.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , p. 10.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , p. 6.

- ^ Annual report of the Department for Foreign Interests of the Federal Political Department for the period from September 1939 to the beginning of 1946, pp. 46–47. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator". Swiss protective power activity between Great Britain and Germany in World War II . Nordhausen 2006, pp. 78-79.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , pp. 16, 22.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , pp. 16-17, 19.

- ↑ Köniz, PTT archive: P-507, activity report of the automobile service , pp. 17, 19.

- ^ Oskar Hauser: The Telegraphist . In: Robert Bratschi (Ed.): My service - my pride . Basel 1941, p. 140-141 .

- ^ Professions of the PTT . In: Städtische Berufsberatung Zürich (Ed.): On the choice of career. Educational leaflet for students in the 2nd and 3rd secondary grades and the other final grades . No. 29 . Zurich 1953, p. 55-56 .

- ^ Professions of the PTT . In: Städtische Berufsberatung Zürich (Ed.): On the choice of career. Educational leaflet for students in the 2nd and 3rd secondary grades and the other final grades . No. 29 . Zurich 1953, p. 62-64 .

- ↑ Yvonne Bühlmann, Kathrin Zatti: Gentle as a dove, clever as a snake and as secretive as a grave. Women in the Swiss telegraph and telephone system, 1870–1914 . Chronos-Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 978-3-905278-96-5 , p. 10 .

- ↑ General Directorate PTT (Ed.): 100 Years of Electrical Communications in Switzerland, 1852-1952 . tape 3 . Bern 1962, p. 733 .

- ↑ Yvonne Bühlmann, Kathrin Zatti: Gentle as a dove, clever as a snake and as secretive as a grave. Women in the Swiss telegraph and telephone system, 1870–1914 . Chronos-verlag, Zurich 1992, p. 252 .

- ↑ Helmut Gold, Annette Koch (ed.): Miss from the office . Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7913-1270-7 , pp. 48-49 .

- ↑ Swiss Post, Telegraph and Telephone Administration (Ed.): Mandatory position for PTT staff . Bern 1940, p. 5 .

- ↑ a b c Federal Statistical Office: Telecommunications Services of the PTT (Telecom) - 1970-1997 | Table. January 30, 1999, accessed April 28, 2020 .

- ^ Patrick Halbeisen, Margrit Müller, Béatrice Veyrassat: Economic history of Switzerland in the 20th century . Schwabe AG, 2017, ISBN 978-3-7965-3692-2 ( google.ch [accessed April 28, 2020]).

- ↑ We, the PTT. Oral History Project of the PTT Archive: About the project. Retrieved on May 24, 2017 (German).