Process and reality

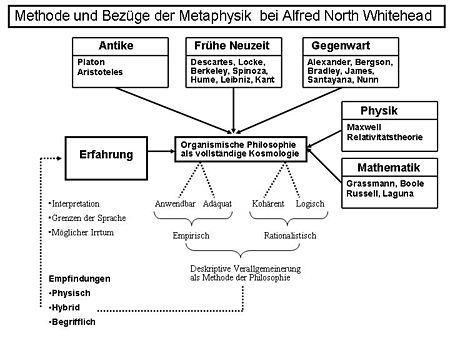

The essay Process and Reality is a work by the British philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) first published in New York in 1929 under the original title Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology . It emerged from the " Gifford Lectures " held at the University of Edinburgh in 1927/28 . The “speculative overall design” is considered - in connection with “Science and the Modern World” (orig. Science and the Modern World , 1925) and “Adventure of Ideas” (orig. Adventure of Ideas , 1933) as the main philosophical work of Whitehead. This was preceded by a long collaboration with Bertrand Russell , the result of which was the basic mathematical work Principia Mathematica . In 1979, Process and Reality was translated into German.

The extremely demanding treatise deals with questions of metaphysics , natural philosophy and epistemology . In contrast to the traditional “ subject philosophy ” and materialistic interpretations of nature, Whitehead designed a system in which the universe is not composed of substances , of passive matter , but of elementary, interlocking and interwoven processes and relationships . This work is a cosmology as an investigation of reality and the relations between different aspects of beings , because Whitehead included all mechanisms and structures of nature including man and his culture in his metaphysical theory . Whitehead thought of the world as a holistic, structured and creative organism that harmoniously embraces man, the world and God . Here he laid the foundation for his “ontological principle”, according to which there is nothing in reality that is not built up from its ( atomistic ) basic events.

With the waning of the focus of analytical philosophy on language , Whitehead's metaphysics became increasingly important towards the end of the 20th century, because it was based on modern approaches in quantum physics , systems theory and cognitive science , research in biology or ecology , but also new concepts of theology can be reconciled. Whitehead's famous quotation about the “characterization of the philosophical tradition of Europe” as “a series of footnotes to Plato ” (PR 91) also falls into process and reality , whereby he did not associate any devaluation of other philosophers, but emphasized that due to the wealth of thought there was no successor could do without a dispute with Plato.

Classification in the Whitehead plant

Whitehead was a mathematician by training but also lectured on physics. He became famous for his basic work on mathematics, especially for the work "Principia Mathematica", which he wrote together with Russell . He did not write his first natural philosophical writings until he was around 60 years old: An Inquiry Concerning Principles of Natural Knowledge (1919), Concept of Nature (1920) and The Principle of Relativity (1922). In this work he had already formulated a number of basic ideas for his approach. However, they are not considered part of Whitehead's developed process philosophy. He had never attended philosophical lectures. His work subsequently appears independent of the relevant traditions, even if he has dealt intensively with the history of philosophy and intellectual history and measured his own thoughts against them.

At the age of 63 he moved to Harvard University in 1924 , where he received a professorship in philosophy and was able to work out his theory. Here his writings Science and the Modern World (1925, German Science and Modern World), Religion in the Making (1926, German How does religion come about? ) And Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (1927, German cultural symbolization ) appeared. These works represent further building blocks in the development of Whitehead's theory, some of which contain revised conceptual concepts, such as the notion of space and time , compared to the first works . In 1927 Whitehead was invited to give the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh . The 10 lectures resulted in Process and Reality with a total of 25 chapters, which was published in 1929 and is to be understood as a further elaborated sum of the previous work. Adventures of Ideas (1933, German Adventure of Ideas) and Modes of Thought (1938, German ways of thinking) appeared as important works . In both writings he essentially explained basic ideas from process and reality , with the history of ideas and questions of civilization being a focus. Whitehead pointed out in the preface to Adventure and Ideas (p. 75) that this book complements his other two writings, Science and Modern World, and Process and Reality, in some ways. In a third subsequent correspondence The Function of Reason (1929, dt. The function of reason ), he discussed the contrast between practical reason , which is the basis of the application of existing knowledge, and the speculative reason, created by the new by existing methods and Conceptual patterns are exceeded.

Structure of the plant

One of the problems with capturing the contents of Whitehead's process philosophy in process and reality is that this work is not structured linearly in that it develops the thoughts step by step building on each other, but that Whitehead thinks through and problematizes the same topics from different perspectives. This makes the work appear circular. Process and reality is divided into the following main parts:

- Part One: The Speculative Scheme

- Second part: discussion and application

- Third part: The theory of detection

- Fourth part: the theory of expansion

- Fifth part: final interpretation

In addition to the presentation of his intention and fundamental scientific-theoretical and linguistic-philosophical considerations, Whitehead presented in the first part a category scheme that includes his entire metaphysical system in a series of conceptual definitions and basic statements. Here all basic terms are introduced largely without explanations. The rest of the book is designed to explain and execute this basic structure in several passages.

What is meant by the terms and how the aspects are related to one another is explained in the second part. Again, aspects such. B. from the theory of perception or through the idea of space and time, which are only presented in full in the following parts. Part two also contains extensive debates with earlier philosophers, on whose ideas Whitehead built his own theory, partly agreeing, partly rejecting.

In part three, Whitehead elaborated on his theory of experience, the theory of perception, the connection between subjectivity and objectivity, the theory of consciousness and thoughts about higher phases of experience. While the third part deals primarily with the inner perspective of becoming, with the interplay of physical and mental phenomena, the fourth part contains a very dense exposition of Whitehead's idea of the spatiotemporal structures of the world. Some of these thoughts are presented in more detail in earlier works on natural philosophy, even if there are further developments in terms of content. The final part mainly explains how, in the metaphysical image, which is strongly influenced by natural science, an idea of God can be thought of as a bracket for the connections in the world.

claim

In the first chapter ("Speculative Philosophy"), Whitehead formulated the claim of his endeavor to "design a coherent, logical and necessary system of general ideas on the basis of which every element of our experience can be interpreted" (PR 31). A broad framework is set in this claim; it is the attempt to develop a metaphysics that does not separate scientific, religious and philosophical questions from one another, but rather captures them in a uniform conceptual system. He rejected a separation of the natural sciences and the humanities and emphasized the endeavor to see a “treasure trove of human experience” (PR 35) in all areas of human thought (e.g. physics, physiology, psychology, aesthetics, sociology, etc.) contributes to an adequate (applicable in all areas) and speculative-coherent (interrelated) metaphysics. (PR 32) Speculative philosophy, which seeks to grasp its subject matter through speculative generalization, must withstand the results of concrete empirical experience and at the same time serves to criticize inadmissibly simplistic ways of thinking. “Everything that is found in 'practice' must be within the reach of the metaphysical description.” (PR 48) As scientific knowledge advances, the system developed by Whitehead must be open to further elaboration, corrections and changes.

In the introduction Whitehead presented a catalog of "myths and erroneous practices" (PR 24-25), which he rejected:

- “(I) The distrust in speculative philosophy.

- (ii) Confidence in language as an appropriate expression of statements.

- (iii) The philosophical mindset that implies and is implied by a faculty psychology.

- (iv) The subject-predicate form of the expression.

- (vi) The doctrine of unqualified reality.

- (vii) The Kantian doctrine of the objective world as a theoretical construct based on purely subjective experience.

- (viii) Arbitrary deductions in arguments ex absurdo.

- (ix) The belief that logical contradictions may point to anything other than previous errors. "

Whitehead's stated goal is to overcome these Descartes and Newtonian ways of thinking. He wanted to develop a philosophy that is in harmony with the findings of modern natural sciences , not only in physics , but also in biology or psychology . This cannot be achieved through strictly empirical research methods, as Bacon had called for. Purely inductive approaches do not allow progress because they lack creativity, imagination and spontaneity. Whitehead described the actual course of science with a metaphor that corresponds in content to the sequence of abduction , deduction and induction in Peirce :

- “The true research method is like a flight path. It takes off from the basis of individual observations, floats through the air of imaginative generalizations and then submerges itself again in new observations that are sharpened by rational interpretation. "(PR 34)

From the analytical examination of experience, a hypothesis emerges in a creative act . This is formulated as a logical and coherent theory . And the correctness ( adequacy ) is checked on the basis of use cases and transferred to other areas. Whitehead's hypothesis was that the world as a whole, but also at the micro level in its atomic constituents, is an organism whose primary principle is an incessant, interwoven becoming and not a being. His theory is a speculative metaphysics, which he repeatedly confronted with empirical facts from all areas of practical and scientific life up to quantum physics .

Whitehead's goal was to close the gap between philosophy and science, which in his day had been a huge gap. He warned against what he called "fallacy of misplaced concreteness" ( fallacy of misplaced concreteness ) (PR 184-185). In the positive sciences the mistake is widespread that concrete events can be explained by abstracts. A map or a menu cannot replace and function as the experience of a walk or a meal. They are models of reality. Empirical and quantitative methods can only depict part of the world of experience because they are model-like abstractions . Whitehead emphasized that every abstraction takes its starting point from concrete objects of the world of experience, but not the other way around (principle of abstraction). A subtype of this error is the “ fallacy of simple location” , which is based on the assumption that “things” exist in the world at certain points in time and space, isolated and independent of one another. This violates the "principle of relativity" according to which any adequate theory must be based on entities that are related to one another. Concepts are also abstractions that describe experiences but can never fully grasp them. What the human mind constructs is not enough to describe reality. “Consciousness requires more than just fiddling with theories. It is the feeling of the contrast between theory as mere theory and fact as mere fact. The contrast is whether the theory is correct or not. ”(PR 350) Whitehead wanted to create a meaningful connection between the two levels. His metaphysics was intended to give creative impulses to a collaboration between philosophy and science.

Because Whitehead was convinced that all speculative metaphysics is always provisional and must adapt to the advancement of knowledge, he was also convinced that every philosophical theory is at some point out of date. He warned:

- "In the philosophical discussion the slightest hint of dogmatic certainty regarding the finality of assertions is a sign of folly." (PR 27)

The problem of language

With his conception of language as a symbolic abstraction (PR 339), Whitehead questioned the philosophy of language if it takes the view that language is the only means of knowledge and an appropriate representation of the real world. This applies not only to his time - although Whitehead did not go into the current discussions at the time at Wittgenstein , Cassirer or Heidegger - but already to tradition.

- "The excessive trust in linguistic expressions was known to be the reason for many weaknesses in philosophy and physics among the Greeks, as well as among the medieval philosophers, who continued Greek traditions." (PR 46)

According to Whitehead, the basic problem of language lies in the fact that it can designate individual phenomena, but never fully describe them, because their concepts are always abstractions . “The language is thoroughly indeterminate, since every occurrence presupposes a systematic type of environment.” (PR 47) The value of a metaphysical theory is measured according to how far it succeeds in approximating its object of description. If it deviates from the conventional usage of the term, this is not a measure of its quality. Whitehead, however, has made extensive and varied use of the creation of new terms and deviating terms. Nevertheless, according to him, completeness cannot be achieved. "Precise language is only conceivable on the basis of perfect metaphysical knowledge." (PR 47)

Whitehead saw the possibility of falling into error through language primarily in the grammatical subject-predicate form of the sentence. This gives the feeling that statements are based on ontological facts, that is, express a truth of being. “According to this view, an individual substance establishes the elementary type of reality with its predicates.” (PR 260) The consequence of this, if not always expressed, assumption is the substance-quality metaphysics that can be found from Descartes to Kant. Based on Whitehead's formula of the "fallacy of misplaced concreteness", the receptionists call this problem of language the "fallacy of perfect dictionary" (error of the perfect dictionary). Without going directly into the debate taking place in his time, in which his student and colleague Bertrand Russell was intensely involved, Whitehead thus strictly rejected a philosophy of ideal language .

content

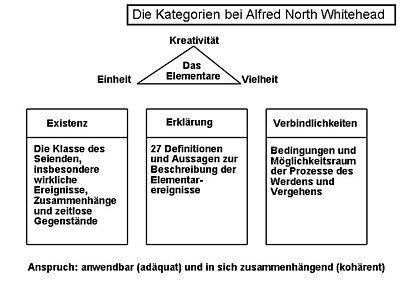

The category scheme

Fundamental to Whitehead's philosophy is a scheme of categories that he developed in order to check the conceptual coherence of his metaphysics, but also to be able to apply his theory to scientific research results. Coherent means that there must be no individual events in the experience that contradict the general ideas (= categories) or even just outside the inner context of the theory. Categories are therefore generally valid terms and fundamental statements that define the framework for the development of a theory. The meaning of the individual categories can only be understood from the overall context of the developed theory. Categories get their evidence by proving themselves in experience. The terms and related statements defined in the categories are mutually dependent and cannot be interpreted in isolation. Whitehead did not claim that the list of categories was complete or so necessary. Its claim was limited to coherence and adequacy. Reiner Wiehl called Whitehead's methodology “ hermeneutic analysis”. Whitehead himself spoke of an envisagement , a term that points to an analogy to phenomenology . Only a few key concepts and arguments are given in this article.

The highest level, which in Whitehead has a similar position as in Aristotle the substance, is the " category of the ultimate" (PR 63). Becoming is a dynamic process in which new things are constantly being created. That is why the elementary category contains the moment of creativity . This is the "universality of all universals" because it is contained as a principle, as an inner stimulating force, as a constitutive quality in all elements of nature. The interplay of unity and diversity also belongs to the elementary. Unity stands for the one , the identity and singularity of individual process elements (Whitehead's term: real individual beings), which in their multiplicity must, however, always be thought of as interconnected. Unity and diversity presuppose one another. In logic they have their equivalent in the analysis of the relation between part and whole. The ultimate individual is a multidimensional, infinite division of the whole of reality. Creativity means that in the process of becoming a new unity, a community (togetherness) (PR 62) emerges from a multitude of elements. The dynamics of the processes mean that each emerging element is something new, something that has never been there before. This clearly shows Whitehead's Platonism . Thus it says in Parmenides (156 from): "The one, then, as it seems, since it grasps being and lets it go, it also becomes and passes away [...] Since it is now one and much and becoming and passing away, it will not, when it becomes one, the being-many pass, but when it becomes much, the being-one pass? "

Whitehead divided the category of the elemental into three categories of existence, explanation, and liability. Categories of existence, as the class of beings, name the basic elements of reality. These include, above all, the real individual beings or real events, relations or recorded information (prehensions) , connections ( nexus ), forms, contrasts and timeless objects as pure potentials. Explanatory categories are used to describe natural events. Whitehead listed what constitutes a process in 27 explanatory statements. The basic thesis is: "That the real world is a process and that the process is the becoming of real individuals." The nine categories of liabilities relate to the subjective internal perspective of real events. They describe the conditions, the space of possibility under which a process that is a real individual can take place.

- “Every individual should be a specific case of a category of existence, every explanation a specific case of categories of explanation, and every condition a specific case of categorical obligations. The category of the elementary formulates the general principle that is presupposed in the three more specific category tables. "(PR 61)

Individuals

Real events as pulses of existence

For Whitehead, the world is made up of “real individual beings” (orig .: actual entity ) or “real events” (orig .: actual occasion ) (both terms are used synonymously): “'Real individual beings' - also 'real events' '- are the last real things that make up the world. It can not be behind the actual individuals go back to something more real find. "(PR 57-58) really means in each case something happens. For Whitehead, “beings” or “things” that remain at rest and “are there” without anything happening do not exist. In addition, reality encompasses a large space, says Michael Hampe : “We traditionally regard dreams, affects, perceptions, thoughts as less real than tables and chairs, stones and trees. […] However, if we take a closer look at our organism or the fine structure of matter, then we see that the persistence, the stability of these supposedly so real things is based on the fact that something happens permanently. ”Real individual beings do not change, but pass away. The impression of persistence results from a constant repetition of continuously successive events of great similarity. In this sense, matter as appearance is constituted from a repetitive sequence of events (not “things”). The idea of matter, like space and time, is only an attribute of real events. This conception of reality can be compared with the concept of dharma in Buddhism (see also: Anatta and Pratityasamutpada )

This shows that, in contrast to other philosophical drafts, Whitehead's endeavor does not consist in sharply separating categories such as “subject” and “object”, “substance” and “quality”. On the contrary, the abstraction of the world into such terms is based more on a “fading out of what is immediately real. In order to see something clearly, it has to overlook a lot of other things. ”The isolation of facts or the construction of“ things ”are already abstractions from the real world. The separation of "appearance" and "reality" leads to a " bifurcation of nature"; Whitehead opposed this idea. The basic concept of the “ontological principle” is not a reductionist one, but rather a complex one; in Whitehead's language: an “ actual entity ”: “Every real individual is 'divisible' in an unlimited number of ways, and each type of 'division' results in a certain quota of recorded information. […]: It relates to one outer world and in this sense is assigned a 'vector character'; it implies feeling, purpose, valuation and causation. "(PR 59)

“Real events” can also be described as “pulses of experience”. They are “feeling” and “felt” acts that each have a fixed place in space and time as the extensive relations of the world with an indivisible volume and time quantum. (PR 129) But one should keep in mind which conception we usually associate with the term "experience". This is explained using an example.

Imagine a person looking at a stone. This situation would be an "experience". We are used to making a clear demarcation between the person, whom we also imagine to be endowed with consciousness, and the stone. Person (a) considers the matter "stone" (b). It would now be the task of philosophy to describe what exactly is going on. In this way of thinking we are entirely in the Descartes tradition and separate spirit and matter, and furthermore imagine the stone as "permanent" - and also the person as consistent (even if with a shorter lifespan); We also assume a date and a clear causal relationship from a (observer) to b (stone). This is exactly what Whitehead does not mean when he speaks of “real events” (or “pulses of experience”).

Person and stone can be seen in a frame, they form the “real event” so to speak - their relationship is the smallest possible unit: it would be a construction to sharply separate the two from each other again. The person “grasps” the stone just as the stone “grasps” the person - each with a different intensity. The intensity of the experience is determined by the story of the person (and the stone). If the person is a sculptor, they will perceive different dimensions in the stone than if they are a bricklayer or baker: in this respect, the prehistory of the person and the prehistory of the stone belong in the overall procedural context of "experience". Experience sets an overall structure: it constitutes itself, so to speak. In addition, it is linked in a complex way to all other “events” that have led to it and that will be influenced by it in the future. And: the “experience” is just a pulse and disappears immediately - but when it disappears, it gives way to a new experience. And in this new experience the previous one is absorbed.

We usually associate the term "experience" with consciousness - that is what Whitehead does not associate. In its conceptual structure, a table consists of “experiences” just like a person or a star.

Since the real individual beings as primordial processes of the universe are the fundamental element of Whitehead's metaphysics, a multitude of detailed descriptions and explanations of this term can be found throughout the work, from which a wide range of meanings and properties result.

Every “real event” has a mental and a physical pole ( bipolarity , PR 438), so that all real events in the world have a spiritual aspect. With this hypothesis, Whitehead's theory of reality is close to panpsychism . The intrinsic value of nature is based on the presence of the spiritual in each of its elements, following a purpose ( teleology ) independent of man . The physical pole is determined by effective causes , the spiritual by purposeful causes . The greater the complexity of a real event, the greater the importance of the ultimate causes. In Buddhism it says: “The mind precedes things; the mind decides. "( Dhammapada , 1st verse)

The nexus

A grouping of real events is a nexus . A nexus is a connection of internal relationships between events which, in contrast to relations, is not subject to any special order conditions and does not have to have a specific pattern. But structured connections, such as a stone or a laugh, also fall under the term nexus. Even a "point is a nexus of real individuals with a certain 'form'". (PR 545) A nexus as a network of real events, as an event constellation, has a space-time expansion. It can be about touches, overlaps, cut surfaces, etc.

“A nexus is a set of real individuals in the unity of relatedness […] established by their perceived information from one another. […] The largest nexus is the world itself, and all other nexus are 'subordinate nexus' compared to it '(subordinate nexuus) ”.

Real events or a nexus are constituted by grasping ("prehension") and creating something new ("creative urge") ; they become more concrete when they have reached their “satisfaction” . In theory, “grasping” means not perceiving Whiteheads, but rather that a relationship is created in the process.

As an example of a complex nexus, Whitehead described the relationship of the ancient Roman Empire to European history. (PR 419 - 421) This includes the city of Rome at the time, the landscape, the people, but also political interests, etc. In this respect, the nexus can be grasped with general terms, universals . This is not enough, however, because the nexus also includes the sensations at that time, ie the spatial and temporal relationships and perceptions that can no longer be historically reconstructed. However, it can be said that at that time there were different real individuals who were ever related to the historical situation from their perspective and who each made a reality for them, so that there are different realities with a high degree of agreement gave. “Even the complex, multiple nexus between many different individual beings in the real world of a perceiver is perceived in this way by these perceivers.” (PR 420) If one disregards the subjective perspectives of the respective perceiver, one obtains a union of the mutually recorded information. "We thus arrive at the idea of the real world of every real individual being as a nexus whose objectification establishes the complete unity of the objective datum for the physical perception of this real individual." (PR 421)

The ontological principle

According to Whitehead, the ontological principle states that every real event has the reason for its existence in itself or in other real events. Everything in the world is related to real individuals.

- "According to the ontological principle, there is nothing that drifts out of nowhere into the world. Everything in the real world can be related to any real individual, is either transferred from a real individual in the past or belongs to the subjective goal of the real individual, in whose concretization it is. [...] The immediacy of the concretizing subject is established by its living aim on its own self-justification. Therefore the initial phase of the aim is rooted in the nature of God and its completion is based on self-causation of the subject-superject. [...] According to this explanation, self-determination is always something imaginative in its origin. " (PR 446f).

The whole of reality consists of individual, concrete, atomic elements that are not abstract. The abstract can only be explained from the concrete. Philosophical thought must be based on this. (PR 57)

Timeless items

On the structure of reality for Whitehead also "timeless objects" include (also called "eternal objects" - eternal objects ), which can be described as abstract properties or relationship structures that are understandable without reference to a specific event. These properties are possibilities or potentials that can be realized in a real individual. These include colors, sounds, smells, but also geometric properties. Timeless objects like the spherical shape or warmth are unique if they can also be concretized in a multitude of real events. They are “particular” in the sense that they differ from the other timeless objects and form a contrast. (PR 107) They are “forms of isolation”. (PR 295) They can only come into reality as potentials in the form of properties of real individuals. Red does not exist in reality without something being red. Red is only potentially possible as long as it is not connected to an actual event. Timeless objects are the only category of existence that does not arise or perish through the becoming of real individuals. They are unchangeable structures, patterns and forms of the universe that are realized in the becoming of real individual beings. The real individual beings get their concrete shape through the timeless objects.

While real individual beings perish in the process of becoming through the connection with other real individual beings or merge into a new real individual being by forming a new context (nexus), the timeless objects remain. They are indestructible, can be repeated and recognized. In this way they enable a persistence in time by being "inherited" from one real individual to the next. They form the space of possibilities (the "potentiality") in which real individuals can realize themselves. As such, the potential of timeless objects is unlimited. But since they are in a real ongoing process, their scope of possibilities is bound to this process. A stone can be wet but not burn. Their potentiality is conditioned in the real world. Whitehead defined:

- "Every individual being that can be conceptually recognized without having to resort to any particular real individual being of the temporal world is called a 'timeless object'." (PR 99-100)

You can talk about “red” or “rectangular” without thinking of anything specific. Timeless individuals have a general and a special aspect. Without reference to concrete, real individual beings, they are “public facts; when concretized in a real individual, they become a quality or a characteristic. The references to the timeless object are public, it can only be experienced "private". "(PR 524 - 525)

The eternal objects are similar to the ideas of Plato or the universals , but not identical to them. The main difference lies in the understanding of relationality:

- "A real individual cannot even be inadequately described by universals, since other real individual beings also enter into the description of every real individual." (PR 107)

Timeless objects cannot be thought of without reference to a possible realization. You have a “relational essence” You stand “in front of things” as a possibility, are “in things” as a realization and “between things” as a reference. They are "found in the things of the outside world" (PR 118) In this relation lies the meaning of the timeless object. The relational character of timeless objects establishes the form of objectification of real events. (PR 123) “Individual things” ( Locke's term) are “grasped through the mediation of universals.” (PR 285) The color red establishes a relationship between the seen object and the seeing subject who grasps the object. On the question of universals, Whitehead was much closer to Aristotle than to Plato. (see also act and potency ).

Subjective goal

The connection between real individuals and timeless objects is the subjective form. This is how a subject records an object, a date. Whitehead also spoke of "private matters of fact" . Through the link, an objective date is merged with an individual subject. "The specification of the initial data on the objective date is made possible by the subjective form." (PR 405)

The question arises as to who or what determines which subjective form is created. This is according to Whitehead, the subjective goal (subjective aim) carries that every expectant real individuals in itself. A subjective goal is the possibility of a future state towards which the becoming of a real event aims. "A single entity is really when it has meaning for themselves." (PR 69) Real individuals have in their becoming not only an impact on their environment, but also a "Selbstbewirkung" (self-functioning) is (PR 70) where the source of creativity. Every real individual is self-creative . It has an aspiration (appetition) , an incentive for the feeling (desire, lure of feelings) to realize itself, to achieve its "satisfaction" (satisfaction) . (PR 170) The question is only taken one step further; because who determines the subjective goal? “No reason immanent in history can be given for why this flow of forms and no other has prevailed.” (PR 103) According to the ontological principle: “Everything must be somewhere; and 'somewhere' here means 'some real individual being'. "(PR 103)

In order not to get into an infinite regress or a circle , there must be an ultimate cause of becoming and passing away - this is the ultimate cause of all possibilities that Whitehead called God. It is the same consideration that Plato asked in Timaeus about the origin of being or why Aristotle spoke of the "immobile mover" in his metaphysics . “The principle of the final cause is a necessary ontological postulate , which, however, cannot reveal itself in its concrete figures in our perception.” The assumption of a primordial reason is a metaphysical thesis, an “as-if condition”, the prerequisite for that one can speak of an intrinsic purpose in real individuals, especially in living beings. All timeless individual beings are contained in God as potentials of the real world. God is the origin of striving and creativity and thus of all subjective goals. ( initial subjective aim , PR 209) It is the nature of God that determines “the special element in the historical flow of forms”. (PR 105-106) God is the beginning. “In the case of the primordial real individual, God, there is no past.” (PR 174) Only God is not tied to history. (PR 100) But it is not the case that God has determined a final subjective goal towards which everything strives, as was the case with Teilhard de Chardin's Omega point . Rather, the story is an open process, always changeable due to the existing space of possibilities. Whitehead refused to contrast beings with a “nothing”, that is, to start from a creation out of nothing ( creatio ex nihilo ). This would be contrary to his realistic worldview. “It is a terminological contradiction to assume that any explanatory fact can flow from non-being into the real world. Not being is nothing. ”(PR 103) In Whitehead there is no transcendence that points to an outside of the real world. Such an idea cannot have reality and is therefore irrelevant.

cosmology

Overall, Whitehead tried in his metaphysics to draw a holistic view of the world (unity, identity ) that can be analytically split up into a multitude of elementary processes that can be viewed from a multitude of perspectives ( pluralism ). For him, a complete cosmology was the undertaking "to draft a conceptual conception in which the aesthetic, moral and religious interests are connected with those concepts of the world that have their origin in the natural sciences." (PR 22) Cosmology refers to the whole field of experience for him.

- "The cosmology has to the same extent the atomism , the continuity , the principle of causation (causation) , the memory, the perception , and quantitative forms of qualitative energy and the extension meet." (PR 437)

The modern worldview was based on physics from Galileo to Newton and has an impact up to the present day. It is based on the idea of a matter and of movement in space and time . The field theory of Maxwell and in particular Einstein's theory of relativity are incompatible with this . Whitehead, himself a physicist and mathematician, was of the opinion that physicalism can only partially explain reality as it is reflected in experience. Above all, mechanistic theories cannot open up access to the processes of biology. But this also applies to the new descriptions of nature in physics, such as in quantum mechanics . The modern natural sciences no longer know inert matter. The new worldview leads reality back to energy and to processes in which structures mutually influence one another. A space-time continuum is opposed to Newton's empty space . Sciences can only ever deal with a part or aspect of nature and thus necessarily leave a remainder, no matter how big or small, unobserved.

Against the mechanistic worldview, Whitehead set the idea of nature as a whole organism in the constant process of creation, which is composed of a multitude of sub-processes and substructures that constantly interact and act on one another in constant relationship. There are processes of transition (transition) and processes as elaborated by coalescence (concrescence) . An organism is made up of the smallest elements (atomism) and is subject to constant changes (continuity). It is a continuous field that is not self-contained but is relative to other organisms. Every organism is constitutive for other organisms. In modern natural science we know molecules, atoms, protons, electrons and energy quanta that form structures and are connected in processes. Nature is not made up of things or separate particles of matter. The idea of things is already an abstraction. The functional principle of a machine does not result from its parts. Printed letters are made up of pixels. They acquire their purpose, their subjective goal, only when they are given importance . Things are passive, derivative, secondary phenomena that result from the repetition of the underlying processes. But nature is an always active, active process of organically connected elements. Complex organisms are more than the sum of their parts and cannot be mechanistically derived from the addition of things.

Ontologically , Whitehead's metaphysics is a monism . Nature is the all-embracing whole based on the unified basic principle of real events. At the same time, an open pluralism results from the infinite possibilities of the interplay between the real events . Whitehead abolished the idea of a bifurcation of nature, which had existed since Descartes, in body and mind by assigning the real individual beings as the elementary building blocks of the universe both a physical pole of experience and a spiritual pole of striving. (PR 483 and 621) With him, nature is not divided, but it contains different categorical aspects. The physical pole is concrete and limited. The spiritual pole is absolute and comprehensive. The physical pole is causally determined by determinations of the other events. The spiritual pole is self-determined through evaluation (valuation) and transformation (transmutation) . Both act on sensations ranging from rudimentary individual physical sensations to reflective awareness and judgment. Spiritual pole is not to be equated with consciousness. The distinction mental / physical rather describes two aspects of reality, "which one could also call the renewing and sustaining aspect." Everything in nature contains a striving, a creative element. It no longer makes sense to differentiate between an animated and an inanimate world. Every shape, every organized structure, be it inorganic or organic, is assigned a subjective, process-related becoming in Whitehead. Conversely, every subjectivity is part of nature.

- “In every concretization there are two aspects of the creative urge. One concerns the emergence of simple causal sensations and the other concerns the emergence of conceptual sensations. "(PR 438)

With this understanding, the question of the subject-object split arises just as little as that of the mind-body problem. Because “part of the essence of a 'being' is to be a potential for every 'becoming'.” (PR 101) Whether a real individual is a subject or an object depends on the perspective. Real individuals have an inner perspective (subject) and an outer perspective (object). Real individuals are in a constant exchange and are therefore always conditioned and themselves a condition for other real individuals. This is "the principle that every act of becoming must have an immediate successor if we admit that something becomes." (PR 143) In the external perspective, the influence of physical causality corresponds. Whitehead criticizes Hume's argument that causality cannot be observed and that it is only accepted on the basis of habit. Hume consider the effects only in the mode of perception of mediating immediacy (see below) and ignore the causally effective, but often only unconscious perception. Against the example of Hume's billiard balls, he set the experience that one instinctively blinks at sudden glaring light. Here the causality becomes immediately apparent. “I know because I feel it.” (PR 326) The awareness of the temporal sequence that Hume addresses is only the result of experience.

The transfer of the causal effect to the inner structure of a real individual takes place through "grasping" ( prehension , see below) and "feeling" (feelings) . The influence of the environment leads to an inner, immanent causality. The hit billiard ball "feels" the energy acting on it and begins to roll. Sensations include both the objective and the subjective aspect of an event. Experience (experience) is not only experience of something, but always also experience for anything. The reaction of the subjects is physically determined, but subjectively the subject has a potential. A solid wall would not move because of a billiard ball. The degree of potentiality depends on the complexity of the real event. This creates higher forms of perception (see below) on the level of life. The most complex forms that also develop consciousness are then the mammals.

With potentiality, Whitehead expressed that in every subject there is not only a reference to the past (causality), but also a reference to the future ( finality ). Even if it is conditional, the subjective side of a real individual contains a moment of creativity that translates into spontaneity and freedom. Organisms have their own dynamics that cannot be justified from external causality. You need an orientation so that orderly structures can arise at all. Whitehead concluded that every subject has a final cause because of its possibilities. For him real individuals are self-organized. By recreating themselves in the development process (concrescence) , they are pursuing a purposeful goal. Organisms are according to “ Spinoza's definition of substance die causa sui ”, the cause of themselves. (PR 175) “The freedom inherent in the universe is based on this element of self- causation .” (PR 175) The subjective goals, such as values and intentions , go as the ultimate causes in the process, but are also determined by it. (PR 168-169). In the external effect, in addition to the causal relationships, the final cause comes from within as an active principle, so that externally the events are not (solely) causally determined. In the subjective perspective, however, the person is determined by all events in the past, including his reflections and evaluations of the impulses coming from outside. In this respect, Whitehead could say that real events are "internally determined and externally free". (PR 73) Internal determinacy also includes the ability to make decisions about the way in which a possibility is realized.

Creativity, the striving in the process, the momentum of real events, is the reason of evolution at Whitehead.

- “The world creates itself; and the real individual, as a self-creating creature, passes over into its immortal function as a part-creator of the transcendent world. In his self-creation the real individual is guided by his ideal of himself as an individual fulfillment and as a transcendent creator. The experience of this ideal is the 'subjective goal' on the basis of which the real individual is a certain process ”(PR 169)

Darwin's theory of evolution is mechanistic like traditional physics. There is no creativity in it. It cannot therefore explain how progress is made. According to Whitehead, evolution is not just a process of selection, a defensive struggle for survival, but an active pursuit of a higher intensity of self-realization, of self-transgression. Intensity is the degree of contrast and complexity. Organisms have a certain vagueness in their reaction to external impulses. Despite all the certainty, there is always something left to make a decision. (PR 73) Decision is "the elementary modification of the subjective goal [...], the basis for our experience with responsibility, approval or rejection, self-respect or contempt, freedom and emphasis ." (PR 104) "The triggering fact is the primordial one Strive, and the final fact is the decision of emphasis, which ultimately works out creatively in 'fulfillment'. "(PR 106)

The higher the complexity of the organisms, the greater the possibility of a decision. Striving can already be observed in single-celled organisms or bacteria . "But animals, and even plants, in lower organic forms display behaviors that are geared towards self-preservation." (PR 330) At higher levels, especially with conscious beings, this leads to them being free to make decisions hold true. This thesis agrees with the theory of dynamic systems in modern systems biology , according to which “for many living processes there are actually several possible paths which they can choose.” According to John B. Cobb, one theory of such decisions is “ genetic assimilation ", The so-called" Baldwin Effect ", according to which behavior-based adaptations in the animal world lead to different phenotypes . In this case, selection is not based on random genetic mutation . One can assume a subjective purpose in it. “Life is a striving for freedom” (PR 203). On the other hand, creative freedom (PR 314) also leads to the possibility of error. (PR 315)

- “The art of progress consists in maintaining order within the framework of change and change within the framework of order. Life defends itself against being embalmed alive. "(PR. 606)

- “[...] every real individual has the freedom that is laid out in the primary phase, which is 'given' by its position relative to its real universe. Freedom, being given and potentiality are concepts that presuppose and limit one another. "(PR 253)

The order of nature

Order is a term that applies to the object-oriented data for particular real individuals. (PR 176) Order arises from the subjective goal of real events. Without order, the world would be unstructured and contradicting itself. Without structures there would be no physical universe and therefore no life. The degree of order can be described as intensity . With "order of nature" one refers to the area of the real universe that is accessible to humans through observation. “No real individual can go beyond what the real world as a datum allows him to be from his point of view - his real world.” (PR 166) This is the ontological principle that determines the order of nature.

Societies

Whitehead developed a hierarchy of groupings of real events in process and reality for the description of larger ( macrocosmic ) structures, which are determined by increasingly specific characteristics (defining characteristics) . The more specific the characteristics, the greater the intensity of the order. To denote the groups of real individuals, Whitehead used the term "company" (society) . A society is a nexus of real individuals who are self-supporting on their own, orderly basis. This means that a society is more than the sum of its parts. (PR 176) Societies have their own form element, a defining characteristic similar to the substantial form in Aristotle, on the basis of which it is determined which real events belong to them. Even the smallest physical objects such as protons are an ordered nexus of real individual beings, i.e. a society. The class designation of a society is derived from information shared by individual elements, the cohesion and reproduction of which results from positive feelings (prehensions) associated with them . (PR 84) Societies contain “an incessant transformation of webs of intersubjectivity”. Through their element of order, they form the environment for each of their individual elements. More complex societies have several intertwined strands (strands) of forms that they "inherit" in the process of arising and passing away. (PR 84) Inheritance and interdependence lead to a spatiotemporal stability of society. The process of becoming and the creation of something new also means that laws of nature only arise in the development of order.

Societies can be structured if they have hierarchical relationships. A molecule is a subordinate, structured society within a living cell , provided it has certain properties that are characteristic of belonging to this cell. (PR 194) Within a cell there is an “empty space” between the molecules, which has no characteristics of its own, so that it is not a (structured) society, but only a subordinate nexus. “ Crystals are structured societies; this cannot be said of gases in a significant sense, although the individual molecules are structured societies. ”(PR 195) One end of the chain of connected societies is the totality of all real events. Conversely, the assignment of more and more characteristics results in a hierarchical order of nature as the real universe. Whitehead specifically named the following levels (PR 189-201):

- Without a specific order, the physical world is an “extensive continuum”, a pure expanse, that is, a totality of all real individual beings, the characteristic of which is an indefinite relationship. Its properties are those of a context of meaning and the opposition of the whole and the part. The science type is metaphysics.

- On the next level, one recognizes a “geometric society” as spatiotemporal givens through direct observation (inspectio) , which is characterized by metric relationships as the fundamental relationships of the universe. The corresponding science is geometry , whereby there is no superordinate or subordinate order between the different geometries (Euclidean, oval, projective, hyperbolic).

- Within the geometric society there are the “electromagnetic societies”, which are determined by an additional set of physical relationships. The metric of these electrical or physical structures is specified by physical laws. Physics and chemistry deal with the electromagnetic level .

- Higher, more complex structured societies are “physiological societies”. These are examined in biology . You develop self-preservation responses. If a society contains striving, one can speak of life . A 'living' society always includes some 'living events'. The transition from the inorganic to the organic is fluid.

- Whitehead mentions psychological physiology as the final stage; its subject is the person whose type of science is psychology .

Social and personal orders

Whitehead advocated the "thesis that every society needs a wider social environment" (PR 196). Structures of order can only be established through integration into the environment. (PR 189) The environment is decisive for the stability and lifespan of a society, which must always be thought of as duration. “[…] The favorable background of a wider environment either disintegrates itself, or it ceases to favor the continuation of a society beyond a certain stage of growth: the society then no longer reproduces its elements, and finally it disappears after a phase of disintegration the picture plane. ”(PR 179-180) Whitehead distinguished between societies that form a“ social order ”and those that he called“ personal order ”. (PR 84-85) A nexus has a social order when there is a common form element for the real individual beings contained in it, a unifying characteristic immaterial principle, through which the nexus or the society it forms in relation to other nexus / Companies can be delimited. Such a form element arises when one or more members of a nexus grasp a simple or complex timeless object that is reproduced (inherited) within the nexus. The "form", like the substantial form in Aristotle, is the defining characteristic of society, which determines its particularity. Societies are galaxies, planets, minerals, plants, animals or elementary particles. Even electrons are societies because they can be localized in space and time and have a history within the processes of the world.

The personal order forms the bridge between Whitehead's process thinking and the general idea of things in experience. A personal order is a social order that forms an enduring object or a permanent creature. Permanent means that the elements of society in their development, in their “genetic relationship”, are “serially” arranged and connected. Real individuals are not permanent but perish. Changes in permanent objects therefore relate to societies and not to a single real individual. These pass. A permanent object is therefore a continuous sequence of real individual beings or societies of social order that are so stable that in this sequence they can predominantly transfer the formal properties to the society in which they are incorporated. Whitehead spoke of "inheriting" in a repetition (re-enaction) . Although this definition is consistent with the term “ person ”, Whitehead refrained from using it because a personal order is also given in inorganic entities such as a stone. In the personal order, the atomism of real individual beings is connected with the continuity that arises through the connection in the sequence of real atomic beings. The basic structure of the cosmos has an atomic character and the continuity of the processes has a secondary character. Thus the continuously appearing space and the continuously appearing time only have a derived existence. The cosmos has an irreversible history that presents itself as strands of real individual beings, as corpuscular entities.

Life

As life , Whitehead marked a historical path of real individuals who inherit from one another to a significant extent. (PR 166) The creation of life is an evolutionary process in which the interaction between a society and its environment is of particular importance. Whitehead distinguished between “specialized companies” and “unspecialized companies”. (PR 196-200) Specialized societies are well adapted to the environment and are stable. Non-specialized societies are simpler and less complex. Your nexus has a lower intensity. At the same time, they are more flexible and have a greater chance of inheriting larger changes in the environment. In order for life to arise, societies are required that are both complex enough to be stable and flexible enough to be able to react to environmental changes.

Societies that make the transition to life show a high ability to react to environmental conditions. This distinguishes them from rigidly structured societies such as stones or crystals. They have a particularly high level of coherence. In a living being, movement is supported and carried by the entire system, while in a machine, e.g. B. a robot, parts of the system remain rigid and are moved by a drive. The components of a machine are parts that are separate from each other. The biological system, on the other hand, has its own holistic system. Living societies also have a distinct tendency to react and adapt to new situations. (PR 199) Striving means that a society is not only causally conditioned by the environment. She has a sufficient intensity of sensations. Part of life is a strengthening of the spiritual pole beyond mere reproduction. In addition to heredity, life always contains spontaneity. It includes self-preservation, active creativity, and the pursuit of ends. “A 'living society' always includes some 'living events'. A society can therefore 'live' more or less, depending on how strongly living events prevail. ”(PR 200) However, it is also characteristic of living societies that they have to fall back on other life for their reproduction, for nutrition and metabolism this often with violence and the destruction of other life. "Whether this serves the common good or not: life is robbery." (PR 204)

Theory of Acquisition

"Enduring personality is the historical path of living events, which prevail in the body at each successive moment." (PR 229) Whitehead also regards humans as a sequence of processes within nature. Humans are a sequence of extremely complex societies made up of a large number of equally complex, hierarchically ordered societies. These are the organs, which in turn are made up of cells, molecules and atoms, as well as the subsystems of respiration, digestion or blood circulation and also mental processes. The human organism differs from animal and also from inorganic structures only gradually in that it is more complex.

- “In the real world we see four levels of real events that cannot be clearly distinguished from one another. First, as the lowest level, we have the real events in so-called 'empty space'; second, the real events, which are moments in the life history of permanent, non-living objects, such as electrons or other simple organisms; third, there are the real events, which represent moments in the history of permanent living objects; fourth, the real events, which are moments in the life story of permanent living objects with conscious knowledge. ”(PR 331)

The more complex an organism is, the stronger the influence of its spiritual pole. The theory of capture applies to all stages of real events. The process can be divided into a genetic sequence, a logical structure that cannot be thought of in terms of space or time. The perception, also perception, is determined by five factors (PR 404):

- the sentient subject

- the initial, still unstructured data

- the elimination of data through negative capture

- the objective date that is felt

- the subjective form that gives the objective data the structure

In the process of feeling, the categories of subjective harmony and subjective intensity work, while sensations are brought together to form a subjective unit (first category of commitment). (PR 72-73, also 237) The path of this integration is directed towards the subjective goal. The subjective form determines the qualitative pattern and the quantitative intensity. (PR 428-429) The constant process of real individual beings emerging from other real individual beings connected to them results in a directionality, a vector character of the sensations. (PR 436) This means that the cause is contained in the effect. “The transition from cause to effect represents the cumulative character of time. The irreversibility of time is based on this property. "(PR 434)

The process of capturing is a process of transformation. (PR 540) Whitehead was thinking of physical processes. "The physical theory of the alternative forms of energy and of the transformations of one form into another is ultimately based on the transference which is conditioned by some exemplification of the categories of transformation and inversion." (PR 464)

perception

For Whitehead, perception is not a process in which a viewer watches what is going on on a stage like in a theater. Perception is rather an exchange process in nature, the basis of any experience (experience) is. Here Whitehead followed English empiricism and Kant. Perception is “the appropriation of the date by the subject, with the aim of transforming the date into a unit of subjective feeling.” (PR 336) “It is the basis of every realistic philosophy that Objectified data come to the fore in the perception, which are recognized in their community with the direct experience for which they are data. ”(PR 160) In the process of perception, the existing relations are converted into new relations. The individual perception event, the “drop of perception”, has both a subjective and an objective aspect. Somebody and something enter into a relationship in a perceptual event, which gives rise to a new real event.

The starting point of perception is the "causal efficacy" (causal efficacy) . Whitehead used this to describe the stream of data that is absorbed by the body's organism. Reflexes such as blinking in sudden glaring light have effective causes. “The primitive, original character of direct perception is heredity. The tone of feeling is inherited with signs of its origin: in other words, it is the tone of vector feeling. ”(PR 229) A causal perception is imposing and can only be controlled to a limited extent. In causal perception, relationships and the continuous development of the real, extensive space-time world are recorded. Perceptions on the level of causal effectiveness are initially “vague, uncontrollable and full of emotions” (PR 333) and relate to the past, because only the past can be the date of experience. Accordingly, Whitehead also assigned memory to causal effectiveness, since it is based on the sequence of some historical path (PR 232), which has its origin, like the causation, in physical perception (PR 437). The perception of the inorganic world does not go beyond the causal effectiveness. (PR 331 and 232)

Whitehead called the second mode of perception “ presentational immediacy” . It only comes to more highly developed living beings. This “refined perception is the 'feeling of the simultaneous world'.” (PR 164) It creates a “lively clarity” through the “diversity of sensual visualization” (PR 330). It depends on the causal effectiveness (PR 329), but “comparatively clear, delimited, controllable, accessible to immediate experience and has a minimal reference to the past or the future” (PR 334). The focus of the mediating immediacy is on the spatial aspect of perception. "In this 'way' the simultaneous world is consciously grasped as a continuum of extensive relations." (PR 129) Its contents are primarily sensory data such as colors, shapes, the spatial position and the spatial position of the object of perception in relation to the perceiver. The mode of mediating immediacy corresponds to Descartes' perception theory, which, however, did not cover the level of causal perception at all (PR 234-235). The same applies to Hume, who was therefore able to propose the thesis that causality cannot be observed. (PR 236-241) The mode of mediating immediacy is a state of existence as the actuality of an atomistic real world. Whitehead quotes William James (Some Problems of Philosophy) : “Either our experience is meaningless or unchanged, or it has a perceptible amount of content or change. Our knowledge of reality literally grows with the seeds or droplets of perception. Intellectually or through reflection, these can be broken down into components, but as immediately given they either all come together or not at all. "(PR 141) The distinction between causal perception and mediating immediacy can be compared with the epistemology of Duns Scotus , which is described in" abstractive knowledge "(sensually conveyed = causal) and subdivided into" intuitive knowledge "(direct perception).

The third phase of perception is the "symbolic reference" (symbolic reference) conveys the original between the two forms of perception. The symbolic reference is constitutive for human thinking. “Our experience is complex. It is not only symbolic, but without symbolism (for example in language, in art and architecture, in social habits and customs, in science and religion) human culture is inconceivable. ”“ There is always a symbolic relationship between the two species when the perception of one element of one kind provokes its correlate in the other and reflects in it the connection of sensations, emotions and derived actions which belong to both correlates of the couple and which are also reinforced by this correlation. "(PR 337 ) The symbolic reference is an actively synthesizing and always interpretive process in which a judgment is made by assigning a symbol to a perception and which is therefore prone to error. The content of the perception is given its subjective form through the symbolic reference to which imagination and reason contribute. (PR 332) The intensity of the symbolic reference increases from the pure symbol, e.g. B. the word "forest", up to an attached meaning, z. B. the memory of experiences in a forest. Meaning is what is inferred from a symbol. These can also be emotions . For Whitehead, it is not tied to language. “It is easier to smell incense than it is to produce certain religious feelings; so if the two can be linked, incense is a suitable symbol for such feelings. Indeed, certain symbolic experiences, which are easy to make, are better suited for certain purposes than symbols than written or spoken words. ”(PR 342)

awareness

Personal identity arises from a certain form of nexus, which is a complex permanent society. For Whitehead, consciousness is a quality of the person, not intentionality itself, but a "mode" of intentionality. “Consciousness arises in a process of the synthesis of physical and mental processes.” (PR 443) It is not objective, not an independent entity, but a way of experiencing reality. It is a structure, an element of subjective form (PR 442), a special form of mental states that, like physical experiences, are real events. It always only captures part of reality and excludes other processes (PR 303). Consciousness does not appear until the top level of experience. Causal perception is still unconscious. (PR 303) Only the mediating immediacy enters the consciousness, which in turn can influence this mode of perception. Consciousness is the subjective form of real individuals. Consciousness is not the basis of the process of experience including perception (PR 115), but a possible result of it. Thus the awareness of a temporal sequence can only be gained from experience. (PR 326) Experience processes do not have to be conscious. Conscious perception presupposes the mode of symbolic reference. Only derived, symbolically modified contents enter the clear consciousness. These do not have to correspond to the underlying fundamental facts. What is vaguely perceived, the inner content of experience, was overlooked by Descartes as well as by sensualism . Experience is more than is grasped in consciousness. The relationship between the subconscious and the conscious is fuzzy. Here Whitehead agrees with Leibniz 's distinction between perceptions (indistinct) and apperception (clear). Consciousness can have different intensities.

- "Consciousness flickers, and even where it is brightest, there is a small focal area of clear enlightenment and a large area of penumbral experience that reports in obscure premonition of intense experience." (PR 486)

An essential characteristic is that “there is no consciousness without statements as an element in the objective datum.” (PR 445) Thus, consciousness presupposes the entry into the symbolic reference. In addition to symbolization, it is part of the awareness that there is a contrast in the perception between what actually is and what could and is not. (PR 444 and 486) The contrast creates a demarcation of the individual that has become conscious. "If the contrasts and identities of such sensations are felt for their part, we are conscious." (PR 350)

- “The triumph of consciousness goes hand in hand with the negative intuitive judgment. In this case there is a conscious sensation of what could be but is not. […] It is the feeling of absence, and it feels this absence through the ultimate exclusivity of what is actually given. Hence the expressiveness of negation, which makes up the special characteristic of consciousness, reaches its climax here ”(PR 497)

Subject - superject

Whitehead took a traditional view of the term subject. For him, the subject was not a substance that remains constant in the course of the process of experience, not even as a Kantian borderline concept, but the inner perspective of a real individual, which is itself a process. Traditionalist philosophy presupposes a subject as substance and contrasts it with an object. Whitehead explicitly contradicted what Kant called the "Copernican turn" that the subject constitutes objects.

- “Organistic philosophy reverses this analysis and explains the process as a course from objectivity to subjectivity, namely from the objectivity, on the basis of which the external world is a datum, to the subjectivity, through which there is an individual experience.” (PR 292)

The real individual is in a constant process in which it absorbs other real individual beings into itself. This process is the subject that represents the inner moment, the intrinsic properties, of a real individual. Subjects do not underlie the processes in the world, but arise only in the process of becoming. They are not a source of experience as is ascribed to the dualistic mind, but they are experienced in the process. At the same time, the real individual stands in contrast to other real individual beings. These contrasting real individuals are objectified for the subject. Objects represent a potentiality for a subject. The subject as a self-generating, real individual captures information about the world outside of it. Objects recorded positively have an impact on the subject. Objects recorded negatively lead to a demarcation, to a final exclusion (PR 94). Due to their contrast, they are significantly involved in the creation process of the respective subject. (PR 414) Because objects are always subjects from their own perspective, subjects objectify one another. They are the "potentiality of 'objectification' in the becoming of other real individual beings." (PR 66)

Parallel to the actual perception phases differed Whitehead in a kind of theory of experience, the sensing (prehension) events, including the perception heard three levels of sensations (feelings) , in which the perception is processed, namely physical, conceptual and expressive form Sensations. He also referred to this as the “reactive”, “complementary” and “spiritual” phase of the experience. (PR 335-336 and 392-394) Experience is the completion of a process. The intensity of the experience is a question of the intensity of the contrast with other real events. The phases of the sensations represent the process of self-constitution. They correspond to the spiritual pole of real individuals. Sensation is the transition of data from the external world into subjectivity. (PR 93) It is the link between subject and object, in which the experiences grow together into a unit of experience (concrescence) . In capturing, the capturing subject, the captured object as a date and the subjective form, i. H. the way the subject records the date together. (PR 66) The recorded data are adopted, changed, weakened or intensified or negated as a contrast according to the subjective goal of the actual recording event. In physical sensation, initial data arise through the encounter with other real events. In this reactive phase, sensations of other real events are absorbed. Events, that is, the recording of repetitive real events, require memory. With decreasing contrast, with habituation, the intensity of memory decreases. The highest intensity of the contrast arises through attention and the experience of the new. The intensity of the contrast also depends strongly on the conditions of the experience, the previous history. A walker in the forest views a tree differently than a forester or a lumberjack or a carpenter. There is a different subjectivity for everyone.

In conceptual prehension there is no longer any direct contact with the outside world. Rather - determined by the subjective goal - evaluation categories (conceptual feelings) are formed as timeless individual beings and thus the recorded data is supplemented. These determine the intensity and form of the experience. An immediate privacy (private immediacy) arises in which the subjective goal can also change. Whitehead understood a term as the analytic work of universals. In the fulfillment as the third phase, the physical and conceptual sensations are finally linked to form a “logical subject”. There is an integration of the physical pole and timeless objects. It is the phase in which the potentiality timeless objects actually (actual) is. In doing so, recorded data can be reproduced, but a new type of individual can also arise. (PR 348) or the prevailing data is not recorded, which leads to the disintegration of the nexus (PR 350). The propositional feelings are a conclusion from the first two phases. It is the result of the process of a real individual, which Whitehead in a neologism called "superject", confronting the subject as the content of the process of a real individual. While the aspect of the subject addresses the inner, private sphere of a real event, the superject expresses the objective side of the event, which is public for other events. (PR 524) The superject is the goal towards which a real individual is constituted. It is a teleological self-creation ( teleological self creation , PR 406). In the superject all possibilities of becoming have become determinations. Every superject, every fulfillment of a real individual, is not static, however, because it contains the potentiality to enter a new process, to acquire new content (acquisition of novel content) , to enter a new real individual or to serve as a contrast. (Principle of relativity)

- “It is essential for the teaching of organistic philosophy that the concept of a real individual as the unchanged subject of change should be completely abandoned. A real individual is at the same time the experiencing subject and the superject of his experiences. It is a subject-superject, and no half of this description can be disregarded for a moment. "(PR 75-76)

The characterization of the subject as subject-superject tries to make it clear that the subject is always something that is experienced (result) and experiences in an ongoing, self-constituting process. The subject does not create the process of experience, but is a constantly changing element of it, something becoming, and as a result the superject, what has become with spatiotemporal determinacy, which contains the potential to enter into a new real event, into another. The superject absorbs the whole history of the subject and is at the same time a condition of possibility, an anticipation of the future that is immanent in it. Accordingly, human subjectivity is also a process of becoming oneself, which in consciousness is a feeling of being aware of oneself. Being a self as a superject is a constant transition into a new becoming. As a nexus connected to a multitude of processes, the human being is a complex event, more than just a personality. As a spiritual being, man can grasp his possibilities and make decisions in his subjectivity, in becoming aware of himself, in consciousness.

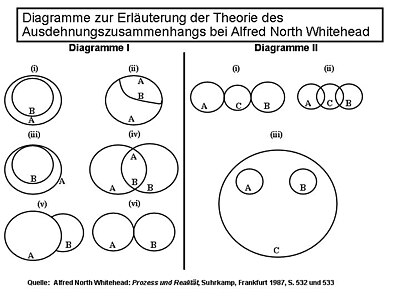

Theory of Expansion

While the theory of apprehension is a genetic analysis of the fundamental processes of becoming, i.e. deals with their formation, the theory of extension looks at the same object of investigation morphologically , i.e. according to its formative structural elements. (PR 513). Both approaches are complementary.

In genetic analysis, Whitehead distinguished three stages in the development of a real individual in the theory of non-temporal apprehension. (Cf. PR 59 and 424-426) In a movement from the outside to the inside, the data of the outside world are first recorded (ante rem). In the second conceptual step, they are evaluated in the subject (conceptual valuation) with regard to the possibility with which the subjective goal can be achieved. The information of the external world is (in re) integrated in the subject in such a way that it either enters into the novelty of the developing real event or is negated and excluded as an object with a contrast. In this function, too, they contribute to the development of the event. The result of this integration process is ultimately fulfillment, the superject (post rem). It has become real and has taken shape.

The emergence of becoming does not yet provide any information about the structure of the external world, since the becoming of a real event does not have a chronological sequence but only its own duration. “There is a becoming of continuity , but no continuity of becoming. The real events are the becoming creatures, and they establish a continuously expanding world. In other words, expansion becomes, but 'becoming' is not expanded. ”(PR 87) Accordingly, the process is the basis of expansion. But expansion is also an indispensable, elementary component of reality.

The extensive continuum

For Whitehead, space and time are extended (PR 129). In the perception of presentative immediacy, the simultaneous world is conceptually grasped as a continuum of extensive (extended) relations. In analysis, according to Whitehead, the mistake is often made of not distinguishing the conceptual abstraction, which relates to pure possibilities, from the real world in which the possibilities have been transformed into reality. The real world of real events is "incurably atomistic". (PR 129) Continuity and the idea of infinite divisibility only exist in thought. The facts arising from the perception are concrete as real events and as these determining relationships and thus not continuously and not indefinitely divisible.

- “An extensive continuum is a complex of individuals united by the multiple related relationships of the whole to the part, the overlap that gives rise to common parts, the touch and others derived from these primary relationships. The concept of a 'continuum' encompasses both the property of unlimited divisibility and limitless expansion. [...] This extensive continuum expresses the solidarity of all possible viewpoints throughout the entire process of the world. "(PR 138)

The whole world is a web of relationships of real events, all of which are directly or indirectly linked in some way. Expansion (extension) is a basic, not more unquestionable writable only in relation to their properties, which is included in each real individuals; it is an "extending something over something".