Rabenstein Forest

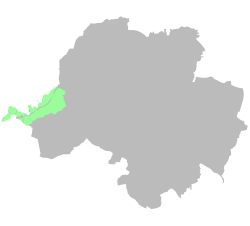

| The Rabensteiner Forest in Chemnitz (green) |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Basic data | |

| Area : | 899 ha (Jan. 1, 2004) |

| Highest elevation: | Totenstein (479 m) |

|

Main tree species (Jan. 1, 2004) |

|

| Norway spruce : | 44% |

| Common birch : | 15% |

| Mountain ash : | 7% |

| European larch : | 6% |

| European beech : | 6% |

| Common pine : | 5% |

| English oak : | 4% |

| Red oak : | 3% |

| Sycamore : | 2% |

| White pine : | 2% |

| other: | 6% (18 species) |

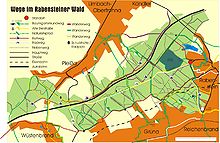

The Rabensteiner Wald is a forest area of around 900 hectares in the west of the city of Chemnitz , a small part is located in the area of the Pleißa district of the city of Limbach-Oberfrohna . It is located on the "Rabensteiner Höhenzug". This ridge separates the northern edge of the Erzgebirge basin from the southern edge of the central Saxon loess loam hill country . Its highest point, the Totenstein , reaches 479 meters above sea level (NN), the lowest point 330 m above sea level. NN . To the west it goes over into the woods on the Langenberger Höhe to the Oberwald reservoir .

location

The Rabensteiner Wald is located on the western outskirts of Chemnitz. Most of the forest area is in the Grüna district and includes small parts of the Rabenstein , Röhrsdorf and Pleißa districts . Since Grüna was incorporated in 1999, most of the forest has belonged to the city of Chemnitz. It lies on the Rabensteiner ridge , an elongated ridge .

Site conditions

climate

The Rabensteiner Forest is assigned to the lower, humid mountain areas and hill country (Uf). In terms of forest, it is assigned to the Oberwald macroclimate form (Ow). The prevailing wind direction is west. The Rabensteiner ridge acts like a wind divide, which has mainly wind directions from west-north-west to the north and west-south-west to the south. In addition, foehn winds from the Ore Mountains, which bring southerly winds, occur.

Climate data from 1961 to 1990

The growing season begins around the 90th calendar day of the year. It takes about 185 days. At altitudes from 380 to 480 m above sea level. NN , 800 mm of precipitation per year measured. About 50 percent of this falls during the growing season. The annual mean temperature is 7.9 degrees Celsius . The global radiation per year reaches values around 1045 kWh / m². In the summer half year it is approximately 795 kWh / m², in the winter half year 250 kWh / m². The potential evaporation is around 582 mm per year. In the summer half year it is approximately 450 mm, in the winter half year it is approx. 132 mm. The climatic water balance results from the difference between precipitation and potential evaporation . It is around 218 mm per year.

Climate data 1991 to 2005

The growing season begins around the 85th calendar day of the year. It takes about 200 days. At altitudes from 380 to 480 m above sea level. NN are 837.2 mm of precipitation per year measured. However, this value is distorted by the very rainy year 2002, which also influences the other values. About 50 percent of this falls during the growing season. The annual mean temperature is 8.6 degrees Celsius. The global radiation reaches values around 1085 kWh / m². In the summer half year it is approximately 820 kWh / m², in the winter half year 265 kWh / m². The potential evaporation is around 615 mm per year. In the summer half-year it is approximately 490 mm, in the winter half-year approx. 125 mm. The climatic water balance is 222.6 mm per year.

Climate data 1901–2005 (long-term trend)

The annual mean temperature increases from approx. 7.9 ° C to approx. 8.2 ° C. The mean annual precipitation falls from approx. 930 mm to approx. 795 mm. The global radiation increases on average from approx. 1040 kWh / m² to 1070 kWh / m², the potential evaporation increases from approx. 575 mm to approx. 600 mm per year and the climatic water balance sinks from approx. 360 mm to approx. 190 mm Year. It gets warmer earlier in the year, stays warm longer and at the same time it gets drier. This extends the vegetation period with increased stress due to lack of water for the plants.

geology

Much of the reason Gesteines takes the muscovite - shale of Ordovician one. Occasions of shale slate and staurolite - mica slate and eye gneiss have been dug into small areas . Only in the south-eastern part below 380 m above sea level. NN there are rocks of the upper tier of the Middle Red lying . These are covered by deposits from the Ice Age ( loess loam ) and modern material from the flowing streams. Tiny deposits of porphyry tufa can also be found here. In the Ordovician, the area was on the southern hemisphere in the sedimentation of the Paleo-Tethys - ocean . Here vast offshore amounts of sediment from that should form the shales in the sequence and under the tremendous pressure converted were. With the unfolding of the Variscan Mountains these were then lifted up. In the Upper Carboniferous and Lower Permian, large parts of this mountain range eroded again. As a result of volcanic activity, porphyry tuffs of the Rotliegend were deposited in some places. These cover the Ordovician slate there. During the Triassic , Jurassic and Cretaceous periods , the area remained flat mainland. At the beginning of the Tertiary the area belonged to a large plain until it was raised and sloped along with the Ore Mountains and the creeks and rivers cut the valleys deeper. During the Ice Age, solid sediments were deposited in the form of loess loam, which to this day has largely been removed from the ridge by erosion and deposited on the lower slopes.

Floors

Most of the forest grows on weathered mica slate soils. The ice age loess deposits are also involved in the formation of the soil. Mostly brown earths can be found. These are spread over the entire ridge of the ridge. They are represented on the flat slopes and ridges in the form of the "Grünaer Schiefer-Braunerde". This is formed as deep (over 65 cm deep), very weakly stony, weakly gritty loamy silt to silt loam . In between there is the "Blankensteiner Schiefer-Braunerde", a medium-sized (35 to 65 cm deep), weakly stony and gritty loamy silt. Staugley , however, is found from about 380 m above sea level. NN in the south-eastern region of the forest to its lowest point. This is often designed as a "Reuther conglomerate humus tugley" and can be found in larger depressions. It is a medium-sized, weakly rocky and gritty loam. The nutritional strength level is mostly "M" (medium nutrient supply) and the moisture level is mostly 2 (medium), on the crests 3 (drier), and in the depressions 1 (more humid). In sloping areas, the soil often allows the water to flow ( seeps into crevices , pores and crevices ), but it often backs up on plateaus and in hollows.

water

Water is only available on the ridge of the Rabensteiner mountain range through precipitation. Groundwater does not rise until then. The rainwater feeds the water-storing soil horizon, the small streams and the few ponds created by humans ( bomb craters or quarries ). These can dry out in summer just like the streams.

Potentially natural vegetation

The natural forest community would be a submontane or (high) colline oak-beech mixed forest ( Lonicero periclymeni-Fagetum ). The spruce, which is the dominant tree species today, would be represented as a subordinate tree species at most in a small area mixed in favorable locations and would otherwise be completely absent.

history

The Rabensteiner Forest has been used by people for a long time. It has been in Saxon ownership for more than 500 years. In the 16th century it consisted mainly of beech, fir, pine, birch and aspen. The spruce was either insignificant or completely absent. There are no indications that wood was “beaten” (= looted forest), so it must have been of high quality. It was given as half a Saxon mile in length and a quarter of a Saxon mile in width. By 1936 the tree species composition had changed radically. Now it mainly consisted of pure spruce stands . The beech, pine and birch as well as aspen were pushed back to the smallest areas. The pure spruce stand was regarded as the most profitable according to the pure soil yield theory and the forest management was designed accordingly with the Saxon clearing system. From 1945 the tree species composition changed again radically. Extensive clearing of even the root stumps and young trees immediately after the Second World War served to alleviate the wood shortage ( firewood ). Substantial reparations in the form of timber also had to be paid. The spruce tree species was pushed back to less than half of the forest area, as mainly birch and aspen grew in large numbers on the cleared areas. Through land reform , agricultural areas were created in parts of the forest, which were later converted into allotment gardens and building land . In the middle of the seventies of the twentieth century, the large routes for the power lines were cut into the forest. At the same time, a start was made to replace the clear-cut stands, which are regarded as less productive and dominated by hardwoods such as birch, with new spruce plantations. This was continued until 1990, so that almost no new hardwood stands were created during this time. The pure coniferous wood could again take up a larger proportion of the area. These stocks are particularly found around the Totenstein today. From 1970, the local recreation area Oberrabenstein was established with the Rabenstein reservoir and the Rabenstein Wildgatter. In these areas the forest has been significantly influenced by the settlement of European wild animals and construction measures. Small stream valleys partially disappeared in the reservoir and forest stands were fenced in and the animals kept in them shape them to this day by peeling , browsing and scrubbing.

Forest condition

Loads

The entire length of the forest is cut up by the federal motorway 4 . The expansion of this motorway in 2006 led to a loss of forest area due to the widening of the lane, road connections and the necessary embankments , rain retention basins and hydraulic engineering systems. Three other streets dedicated to the public, the district road K 7304 (Pleißa-Siedlung Kühler Morgen-Wüstenbrand), the state road S 242 (Pleißa- Wüstenbrand ) and S 244 ( Kellers - Chemnitz-Rabenstein) divide the forest. From the Röhrsdorf substation, large overhead power lines (up to 380 kV) run through the Rabensteiner Wald in an east-west direction and north-south direction. Run on a part of the forest area to recurring pelts because growing up trees may not grow into the security area of the overhead lines and mulch are eliminated. Particularly on the side facing the city of Chemnitz, there is a high level of pollution from people's settlement activities. For reasons of traffic safety , trees have to be pruned or felled that should continue to grow elsewhere without being disturbed. Wild garbage deposits are common and can include household or commercial waste with or without hazardous substances, as well as green waste. Since the forest is a commercial forest , with a few exceptions such as overhangs or solitary trees and avenues as well as standing dead wood, every tree is felled and transported away at some point. In this respect, the forest is very different from a primeval forest .

Tree species

Tree species and area share (in alphabetical order), the data are only available for the forest owned by the Free State of Saxony: Aspe 0.50 ha, sycamore 17.80 ha, Douglas fir 1.20 ha, rotary pine (Murray pine ) 12.80 ha, Mountain ash 62.00 ha, European larch 54.40 ha, spruce (other) 0.20 ha, common birch 125.65 ha, common ash 1.00 ha, common spruce 379.10 ha, common pine 44.90 ha, Gray alder 0.40 ha, hornbeam 0.80 ha, Japanese larch 1.80 ha, coastal fir 0.30 ha, poplar 8.80 ha, red beech 48.50 ha, red oak 23.40 ha, red alder 8.90 ha , Robinia 0.10 ha Black pine 0.40 ha, Serbian spruce 7.10 ha, Stechfichte 0.70 ha, English oak 35,90 ha, sessile oak 3,10 ha, white fir 1.80 ha, Weymouth 14.30 ha, Winter linden tree 0.20 ha

Forest damage

Until the mid-nineties of the twentieth century dominated the classic forest damage, particularly on sulfur dioxide - emissions -based, especially the spruce needles were damaged as a consequence. The topsoil became more and more acidic and finally had a pH (H 2 O) of 3.8 and pH (KCl) of 3.2. With the change in the filter technology of the power plants and the replacement of lignite as the main fuel in the small combustion systems , these gradually disappeared. An improvement in needling on the spruce was observed. The liming of the forest parts, which took place as part of the forest damage restoration in 1997 and 1998, also contributed to this. It supplied the necessary minerals to the humus and topsoil in order to buffer the acidic inputs.

Novel forest damage

With the strong increase in traffic on the A4, the situation deteriorated again. With the death of many trees, the spruce had to bear the main burden of immissions from ozone , nitrogen oxides , abrasion from vehicles and the influence of de-icing salts. An improvement in the situation is currently not in sight, especially since the climate changes will tend to weaken the spruce.

Abiotic and biotic influences

At an altitude of 400 to 600 m above sea level. NN there is often wet snowfall in winter . As a result of the deposits on the treetops, conifers in particular are at great risk of breaking. Many conifers therefore also have older, sometimes extensive and often repeated crown fractures. Entire stocks can also collapse (the damaging event in the winter of 1979 with over 20 hectares of broken land). Due to its location on the ridge of a mountain range, the shallow-rooted spruce in particular is subject to considerable water stress in dry years. This can lead to needle losses, the appearance of bark beetles - mass multiplication or loss of growth. The drier and the longer the drought, the more likely it will mean the end of the spruce. This is especially true on the Staugley soils that then completely dry out and are difficult to replenish. On the other hand, excessive precipitation leads to an extreme softening with the result that the flat roots of the spruce can no longer find a hold and the trees can be thrown by wind and storm or snow load. Game browsing on young trees due to high roe deer populations is on the decline. The main tree species rejuvenate themselves again through seed fall.

Forest owner

The Free State of Saxony is the owner of the majority of the forest area (> 95%) . Small adjacent or protruding parts are private forests , partly owned by farms or other private individuals and communities of heirs or communal forests in the cities of Limbach-Oberfrohna and Chemnitz.

Forest functions

Utility function

Due to the good growth per year, approx. Six solid meters of wood can be felled per hectare. This means that at least 5,400 solid cubic meters of wood enter the economic cycle every year . The wood can be sustainably removed from the forest every year because it grows back again and again. Hunting for roe deer and wild boar is also important . Six to seven deer per 100 hectares are shot every year. Wild boars are added to the hunting route with an average proportion of around one to two heads per 100 hectares. Foxes are also occasionally shot. Other animal species usually only fall victim to road traffic. The hunting route can be up to a ton of venison per year.

Protective functions

Large parts of the forest are located in the Rabensteiner Wald conservation area . In addition, there are natural landmarks such as the FND “Wetland am Goldbach” (one of the few natural brook grounds in the city area) and the FND “Waldtümpel im Forst Oberrabenstein” (former bomb crater ), which contain temporary small bodies of water. The protection purpose in FND "Forest pools in the forestry Oberrabenstein" is the preservation of small bodies of water as amphibians spawning ( Teichmolch , Bergmolch , newt , frog and toad , the area serves to Ringelnatter and blindworm as a living space) and the adjacent, unobstructed, natural stream run against destruction and impairments. The protective purpose of the FND “Wetland am Goldbach” is the preservation and undisturbed development of a natural stream course with stream floodplain forest , small bodies of water, wet heather and dwarf shrub heather as a habitat for endangered animal and plant species. Soil protection forests make up almost 20 percent of the forest area. Almost 20 percent also protect the water. More than 85 percent of the forest area is important for air protection (air renewal and cleaning). Over 75 percent of the area is intended to protect the landscape.

Recreational function

With around 45 percent recreational forest, the forest area is very popular with forest visitors. A variety of activities can be carried out. So you can go hiking, jogging, walking, cycling, walking dogs, riding, climbing ( climbing forest ) Watch Animals (Wildgatter with the species wolf , lynx , wildcat , bison , deer , fallow deer , mouflon , wild boar , roe deer , and Small animals). There are numerous hiking trails of regional and national importance. The "Baumgarten-Rundweg" is a reminder of Georg Baumgarten , the former chief forester in Grüna . The cycle path of the city route leads over the Totenstein and there are bridle paths on both sides of the A4 with connections to the surrounding area. There is also the possibility of collecting mushrooms and berries. A winter sports club uses a ski jumping facility with several smaller jumps in Gussgrund .

Forest operation

Most of the Rabenstein Forest is managed by the Sachsenforst state enterprise . The Sachsenforst state enterprise is PEFC certified . This means that the rules of this certification system must be adhered to. This is guaranteed through independent controls and an internal quality assurance regime. The Rabensteiner Wald provides work for at least eight people (as of 2008) and others are busy transporting and processing the wood.

swell

- Fritz Reinhold: The tillering of the Electoral Saxon forests in the 16th century. A critical source summary. Manufactured on behalf of the Saxon state forest master. Printed in Dresden, v. Baensch printing company.

- E. Dürigen, 1936: Map III of the Stollberger Revieres with the state of the Rabensteiner Forest.

- Otfried Wagenbreth and Walter Steiner : Geologische Streifzüge , Third reviewed edition 1989, Leipzig, German publishing house for basic industry, ISBN 3-342-00227-1 .

- Free State of Saxony, State Ministry for the Environment and Agriculture, September 2008: Saxony in Climate Change - An Analysis. , ISBN 3-932627-16-4 .

- VEB Forstprojektierung Potsdam, 1986: Legend to the location maps of the State Forestry Enterprise Flöha .

- VEB Forstprojektierung Potsdam, 1986: Location map of the state forestry enterprise Flöha .

- State Surveying Office Saxony: Special geological map of the Kingdom of Saxony, Section Hohenstein-Limbach , color copy reprint of sheet 95 (new no .: 5142).

- Land survey office of Saxony: Legend for the special geological map of the Kingdom of Saxony, Section Hohenstein-Limbach , reprint.

- Free State of Saxony, Landesforstpräsidium, 2004: Forest management data .

- Free State of Saxony, Sächsische Landesanstalt für Forsten, 2000: Soil condition survey in the Saxon forests (1992–1997) , series issue 20.

- Free State of Saxony, Saxon State Institute for Forests: Forest function mapping .

Web links

Coordinates: 50 ° 49 ′ 32 " N , 12 ° 46 ′ 42" E