San Clemente (Rome)

| San Clemente al Laterano | |

|---|---|

| Patronage : | St. Clement of Rome |

| Consecration day : | 384 |

| Rank: | Basilica minor |

| Medal: | Dominicans (OP) |

| Cardinal priest : | Adrianus Johannes Simonis |

| Parish: | Santa Maria in Domnica |

| Address: | Via di San Giovanni in Laterano 00184 Roma |

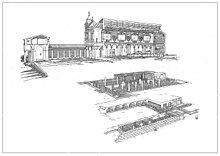

San Clemente, fully Basilica San Clemente al Laterano ( Latin : Basilica Sancti Clementis in Laterano ), is a church in Rome with the rank of minor basilica . It is consecrated to the martyr Clement I , who was Bishop of Rome from 88 to 97 . The church and adjoining monastery have belonged to Irish Dominicans since 1677 .

Location and overview

The basilica is located east of the Colosseum between Via Labicana, which still follows the ancient course of the street, and today's Via di San Giovanni in Laterano, i.e. on the historical pilgrimage route from the Lateran to the Roman Forum .

The overall complex includes on various levels:

- Roman building remains from the 1st to 3rd century (with a mithra of approx. 240),

- Expansion of the ancient rooms as an early Christian basilica with the name Titulus Clementis around 384 ("lower church")

- medieval basilica San Clemente above the level of the early Christian church from 1108 ("upper church").

Previous buildings

In the great fire of Rome in AD 64, the buildings around today's church were completely devastated. Remains of the foundations of a destroyed building, which were reused for the subsequent buildings, were found during excavations. Shortly after the fire, two buildings were erected on the rubble. The larger one (29 × 60 m), located to the east, consisted of a large courtyard and numerous barrel-vaulted chambers made of tuff , which were open to the courtyard. This building may have been a Moneta , a state mint that is said to have been in the area, according to inscriptions.

To the west, only separated by a narrow alley, was a multi-story brick building, the rooms of which were also grouped around a (albeit much smaller) courtyard.

There are two different theories for this building:

The first theory concludes from the elaborate furnishings with mosaic floors and stucco work on the vaulted ceilings that this lavishly furnished building was the stately home of the consul Titus Flavius Clemens . Because the ties legend that the consul, a member of the Flavian imperial family, converted with his family to Christianity and later martyrs died as and that the future Pope Clement I a freed slave was out of this house and as usual, as a freedman the Name of his former master. That is why the entire complex was later named after him.

According to the second interpretation, because of the proximity to the Colosseum and the gladiator barracks Ludus Magnus, which is only one block away , it is more likely that it was a public building that may have belonged to Moneta. An indication of the correctness of this theory can be seen in the fact that in the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus , around the year 200, the small inner courtyard was vaulted and a mithra was built there, which usually happened in public buildings where the employees there were receptive to the mystical , oriental religions.

The question of whether the western building was a private house or a public institution is of importance for the origins of the later church. In the case of a private house, it is conceivable that a house church may have been set up in one of the rooms as early as the 2nd century . In the case of a public building, however, this would be unlikely in the time before Constantine . In any case, a titulus clementis is attested for the 4th century. There are a number of examples in Rome - such as Santa Sabina - that such titular churches were originally named not after a saint but after their founder, and that only later generations were ignorant of pious legends about this name. It is uncertain whether San Clemente is also such a case or whether the church was consecrated from the beginning to the venerated Clement of Rome.

At any rate, the Mithraeum was still in use at this time until the pagan religions were banned in 391 . It is thus impressively documented how different religions were practiced side by side in a very small space in Roman antiquity.

History and description of the building

The alleged Moneta had been abandoned around 250 AD. Then the inner courtyard and the chambers were filled with earth and rubble from the upper floors and a 35 × 29 m hall was built on the foundation, the function of which has not yet been clarified. Around the year 384, this hall was converted into a three-aisled basilica under Pope Siricius (384–399) and was already consecrated to Clement I, who was venerated as a saint. The rooms on the first floor of the Roman building were connected to aisles and the former inner courtyard was roofed over as a central nave . Two rows of eight columns each with arcades separated the ships from one another. The front wall was broken through and a wide, semicircular apse was built on the first floor of the western building - partly above the mithraea . In the east, a narthex was built with five arcade openings into an atrium . A baptistery was also set up on the north side of the early Christian basilica in the 6th century . The early Christian basilica gained special importance through the Roman synods held there in 417, 499 and 595. In 417, Pope Zosimus referred to the church in his letters as sancti Clementis basilica.

At the beginning of the 6th century the interior of the early Christian basilica was renewed, in particular the altar with ciborium and the altar barriers for the presbytery, all donated by the then presbyter Mercurius, who later became Pope John II (533-535). Parts of it were later reused in the upper church, including the choir screen of the Schola cantorum made of Proconnesian marble , some with the monogram of Pope John II. These barrier plates are among the oldest known schola cantorum in Rome . Due to the comparability of the jewelry shapes and the processing with corresponding work pieces in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople , it is assumed that these choir screens come from the same workshop, especially since there were no such high quality works in Rome at that time. In addition, a part of the architrave of the ciborium has been preserved, today built in near the floor of the left enclosure wall inside under the last two barrier plates; it bears the inscription : ALTARE TIBI D (eus) S SALVO HORMISDA PAPA MERCVRIVS P (res) B (byter) CVM SOCIIS OF (fert) (“The altar brings you, God, with the permission of Pope Hormisdas, the Presbyter Mercurius with his companions dar ".)

The columns and capitals of the early Christian ciborium, made of Carrara marble , were also made by Constantinople artists. Two of the capitals have been preserved, one with a wickerwork and a second with openwork acanthus leaves. The capital with the foliage bears the donor's inscription on the edge of the cover plate: + MERCVRIVS P (res) B (yter) SanC (ta) E EC (lesiae Romanae) (servus) D (omin) NI (“Mercurius, Presbyter of the Holy Roman Church, Servant of the Lord ”). These two extraordinarily elaborate capitals have been reused in the upper church on the Renaissance tomb of Cardinal Antonio Giacomo Venerio (at the end of the left aisle).

In 1084 Rome was sacked by the Normans under Robert Guiscard and San Clemente was badly damaged in the process. For stabilization, the arches between the columns were walled up and the areas filled with frescoes - some of which have been preserved - in which the legend of Clement is told. The stabilization measures did not have any lasting success.

Under Pope Paschal II (1099–1118), who was himself a cardinal priest of San Clemente, the ruins of the early Christian church were filled up to the level of the pillars and used as the foundation for today's church (construction period 1108–1128). About 20 m above the level of the Roman period, the new building of a three-aisled, slightly smaller basilica (approx. 40 × 20 m) was built with the following features: The new central nave and the right (narrower) aisle now extend over the previous central nave, while the left aisle will retain its previous dimensions; the main apse is adapted to the narrower nave and is flanked by unequal width side apses. On both sides, four pairs of pillars, each with a pillar at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the central nave ( change of pillars ) support the upper aisle with originally large arched windows , over which an open roof structure. The columns with Ionic capitals are made of different types of stone and have smooth shafts - with the exception of the two columns with hollow strips at the level of the Schola cantorum , which was built into the nave in front of the apse from the barrier plates of the lower church. As cosmatic works of the 12th century were added: the altar ciborium and bishop's throne in the apse, the two ambon and the Easter candlestick at the Schola cantorum , the mosaic floor in all the church naves and the twelve red porphyry panels in the center aisle as a reference to the twelve apostles . This is how one of the most beautiful medieval designs of the nave and choir in Italy was created.

From 1430 the Cappella di Santa Caterina was added. The frescoes by Masolino da Panicale depicting the martyrdom of St. Catherine are among the first works of the Roman Renaissance .

Cardinal Camillo Pamphilj transferred the church and monastery to the Dominican Order in 1645 , before both of them passed to the Irish Dominicans in 1677, who had to flee Ireland during the English Civil War .

From 1715 to 1719 Carlo Stefano Fontana redesigned the basilica in the baroque style. a. with stuccoing and painting of the tall nave walls and installation of a coffered ceiling .

In 1857, Father Joseph Mullooly began the excavations, during which large parts of the predecessor buildings of San Clemente have been rediscovered to this day.

tour

Outside

The exterior of the basilica is very simple and hardly architecturally designed; it consists essentially of flat bricks , partly as exposed masonry and partly plastered. The walling of the original arched windows of the central nave can still be seen on the north and south sides of the former Lichtgaden . Today's church entrance is on the south side through the side portal in the left aisle. The three mountains from the Albani coat of arms of Pope Clement XI are framed next to the side entrance . (1700–1721) can be seen.

Atrium and vestibule

From the Piazza San Clemente steps lead down to the former main entrance, a canopy-like porch with two free-standing Ionic spoli columns and two Corinthian half-columns . Behind it opens the atrium, an almost square courtyard with open hall corridors on the sides, the pent roofs of which are each supported by six spoli columns with architraves; it is one of the last examples of the early Christian design of such a forecourt in Rome. In the middle of the atrium there is a well bowl from the 18th century as the successor to the early Christian cleansing well.

The simple Baroque facade of the basilica with a large arched window and triangular gable, which Fontana created from 1715, rises above the 12th century vestibule with four ancient Ionic columns. The campanile, built around 1600, rises on the southwest side of the basilica .

Upper Church

The upper church shows the traditional sequence of rooms of an early Christian house of worship: gate - forecourt (atrium) with cleaning well - vestibule ( narthex ) - parish room (nave) - singing choir (Schola cantorum) - presbytery with high altar - apse. In addition to the furnishings of the basilica already described, the mosaics in the apse and on the apse arch from around 1118 are particularly noteworthy.

To the left of the main entrance is the aforementioned St. Catherine's Chapel by Masolino (before 1431). He was one of the first artists to come to Rome after the return of the Popes from Avignon . On the right wall you can see scenes from the life of Ambrosius of Milan and on the left the “Vita of St. Catherine of Alexandria ”. In his depiction of the legend of Catherine, Masolino first introduced the central perspective into Roman painting, which his student Masaccio had developed in Florence together with Filippo Brunelleschi .

Access to the lower church has been in the right aisle since 1866; A small lapidary is housed in the stairwell .

Mosaics on the apse and apse arch

In the apse calotte the veneration of the cross is shown as the tree of life under the hand of God appearing from above; next to the cross stand Mary and the apostle John . The large cross in dark blue in front of a golden background is surrounded by five vines that climb upwards in curves, all of which are rooted under the trunk of the cross in the earth soaked in the blood of Christ; According to the inscription running under the mosaic, the vines are supposed to symbolize the steadily growing Christian community that was transformed into a garden of paradise through Christ's death on the cross. In the tendrils below (in smaller proportions) the four church doctors Augustine of Hippo , Hieronymus , Gregory the Great and Ambrosius of Milan as well as men and women can be seen doing their day's work. The paradise garden is depicted at the lower edge : shepherds' scenes and in the middle the four paradise rivers from which two deer drink; just above - in a smaller format - another stag attacking or chasing away a red snake (the devil). Due to the wording of the inscription, it is assumed that splinters of wood from the cross of Christ could originally have been kept behind the mosaic cross . Twelve doves are depicted on the crossbar, which, like the twelve lambs in the frieze below, symbolize the Apostles .

The mosaics of the apse arch show: In the upper zone the blessing Christ with the four apocalyptic beings . On the left (from bottom to top): City of Bethlehem , prophet Isaiah , Paul of Tarsus (with scroll ) and the martyr Laurentius of Rome (with his feet on the glowing grate and with a cross-staff) . On the right side (from bottom to top): City of Jerusalem , prophet Jeremiah , Simon Peter (with scroll) and the Roman bishop Clement I (with an anchor as a sign of his martyrdom). The west wall is painted with frescoes from the 14th century. On the side walls, Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari depicted the legend of St. Clement of Rome in his frescoes.

Lower church

In the lower church, consecrated by Pope Siricius in 384, there was a dedication inscription with the information that the church was consecrated at that time for Bishop Clemens of Rome, who died a martyr; Remnants of this inscription are immured in the left longitudinal wall of the lapidary.

The supports in the former central nave were added later and support the upper church above. On the inner walls of the three naves, frescoes from the 6th-11th centuries could be seen. Century. The wall paintings are emphasized here:

On the left of the entrance wall: Christ enthroned with Andrew , the archangels Michael and Gabriel and Clemens of Rome (9th century); right: miracle of Clement of Rome at the grave in the Sea of Azov; Transfer of the relics of St. Clemens von Alt-St. Peter to San Clemente (868). On the inside of the entrance wall on the left: Ascension Day with the image of the founder Pope Leo IV (847–855) with a square nimbus as a sign that the founder was still alive when the fresco was executed; also: crucifixion, women at the grave, Christ's descent into the underworld and wedding at Cana . In the central nave on the left wall: enthronement of Bishop Clemens of Rome, next to him his predecessors Peter, Linus and Cletus ; Mass of St. Clemens in a catacomb ; Scenes from the Clemens legend; one picture shows how the saint is being persecuted by the captors of the prefect Sisinnius; They tied up a pillar which they - blinded by God - believed to be Clemens, and tried to remove the pillar, urged on by the prefect; whose words can be read on the wall like a comic: Fili de le pute, traite ... ("pulls, you sons of bitches"). In the right aisle there is a niche with a fresco of Maria Regina enthroned with child (7th / 8th century) in the middle right . Not far from it is a pagan sarcophagus from the 1st century, which probably contained a Christian reburial. The reliefs show scenes from the story of Phaedra and Hippolytos . On the apse wall between the nave and the right aisle: Christ in Limbo, where he tramples Satan to free the old Adam; on the left the half-length figure of the (unknown) donor with prayer gesture and book. At the end of the left aisle: two frescoes with the crucifixion of Peter and the baptism of a young man by a bishop. There is also the site that was named the burial place of St. Cyril is said to have served and which was redesigned by the Orthodox Church in the 20th century . From here you can also descend to the lowest floor to visit the Mithraeum and the area of the remains of the imperial buildings.

Ancient excavations

The Mithras sanctuary, which lies outside the basilica's base, is first reached through vestibules. To the right of the entrance is a head with seven rays, probably a portrait of Alexander the Great as Helios (late 2nd century). The Mithraeum consists of a rectangular space under a flat barrel vault with eleven light openings, the seven smaller ones for the planets known at the time and the four square ones for the seasons . There are benches for the believers on three sides. The front of the altar in the middle of the room has a relief with Mithras killing the bull and above it busts of the seasons. On the narrow sides the two torchbearers of the Mithras faith are shown, namely Cautes with a raised torch (as a symbol for the increasing days) and Cautopates with a lowered torch (for the decreasing days). The big snake on the back symbolizes mother earth. Through a modern opening in the outer wall one enters the excavated rooms of the ancient house of Titus Flavius Clemens. At the end of the sequence of rooms, a small catacomb with 16 graves from the 5th century is reached; because after the sack of Rome by Alaric in 410, the general ban on digging graves within the city was no longer observed.

The accessible part of the excavation also includes a visible and audible underground watercourse. This possibly once fed the lake that Nero had built on the spot where the Colosseum now stands.

Significance for the Orthodox Church

The brothers Cyril and Method were sent by the Emperor of Byzantium in the 9th century to proselytize the Slavs. According to legend, they were able to find the relics of St. Find Clement I on the Crimean peninsula and transfer to San Clemente in Rome in 867. Cyril died in Rome in 869 and was also buried in San Clemente. His grave was found during the excavations of the lower church. Kyrill is u. a. the national saint of Bulgaria. Since 1929 the grave has been expanded by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church into a pilgrimage destination, which is regularly (most recently in 2003) visited by the Bulgarian Patriarch.

Cardinal priest

see list of cardinal priests of San Clemente

literature

- Heinz-Joachim Fischer : Rome. Two and a half millennia of history, art and culture of the Eternal City. DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-7701-5607-2 , pp. 236-237.

- Frank Kolb : Rome, the history of the city in antiquity. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39666-6 .

- Leonardo Boyle: San Clemente - Roma. Collegio San Clemente, Roma 1976.

- Hugo Brandenburg : The early Christian churches in Rome. Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1656-6 .

- Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum . Herder, Freiburg 2016, pp. 177–181.

- Gerhard Wolf: Non-cyclical narrative images in the Italian church interior of the Middle Ages. Reflections on the time and image structure of the frescoes in the lower church of S. Clemente (Rome) from the late 11th century. In: Gottfried Kerscher (Ed.): Hagiography and Art. Reimer, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-496-01107-6 , pp. 319-339.

- Patrizia Carmassi: The high medieval frescoes of the lower church of San Clemente in Rome as a programmatic self-representation of the reform papacy. New insights to determine the context of development. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 81 (2001) 1-66 ( online ).

Web links

- Church website (Italian and English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Diocese of Rome

- ↑ Wolfgang Kuhoff: FLAVIUS CLEMENS, T (itus). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 20, Bautz, Nordhausen 2002, ISBN 3-88309-091-3 , Sp. 503-519.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century , Regensburg 2013, p. 151f.

- ^ Frank Kolb: Rome, the history of the city in antiquity , p. 616.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century , Regensburg 2013, p. 151ff.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum . Freiburg 2016, p. 177f. with floor plan development Fig. 19.1.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century , Regensburg 2013, p. 157.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - Ein Vademecum , Freiburg 2016, p. 179.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian Sacred Buildings from the 4th to the 9th Century - Ein Vademecum , Freiburg 2016, p. 178ff. with floor plan Fig. 19.2 and reconstruction drawing Fig. 19.3.

- ↑ Anton Henze u. a .: Art Guide Rome , Stuttgart 1994, p. 166.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum . Freiburg 2016, p. 180f. with text and translation of the inscription.

- ↑ Joachim Poeschke: Mosaics in Italy 300-1300, Munich 2009, p. 206ff.

- ↑ Walther Buchowiecki: Handbook of the Churches of Rome. The Roman sacred building in history and art from early Christian times to the present . Volume 1, Vienna 1967, p. 572ff. with description.

- ↑ Walther Buchowiecki: Handbook of the Churches of Rome. The Roman sacred building in history and art from early Christian times to the present . Volume 1, Vienna 1967, p. 584f.

Coordinates: 41 ° 53 ′ 21.5 ″ N , 12 ° 29 ′ 50.7 ″ E