Swabian volcano

The so-called Swabian volcano is an area geologically influenced by tertiary volcanic activity on the plateau of the central section of the Swabian Alb and its northern foreland. So far, over 350 volcanic vents (diatrems) have been identified within a radius of 56 km . Numerous hidden chimneys could only be mapped using geophysical methods . Since the volcanic activities only took place in the Miocene (17-11 million years ago), after this long time volcanic features are only perceptible in a few cases, in even fewer cases they shape the landscape and very rarely are chimneys on the surface visible. At the very small Scharnhauser volcanic vent, around 23 kilometers north of today's Albtraufs , rock fragments from the White Jura (Malm beta) were found, where all three Jura levels have long been eroded. In the Miocene, the Alb plateau must therefore have extended until shortly before Stuttgart.

Landscape in the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area

Since the extinction of volcanism in the Miocene (approx. 11 million years ago) there has been no further activity. After this long period of time, volcanic features are only perceptible in a few cases and in even fewer cases they shape the appearance of the landscape. Chimney tips visible on the surface are rare. Rhenanische erosion , weathering and erosion of the reliefs of Albplateaus by m up to 200, north of the present Albtrauf often 300 m or more, the tops of have volcanic vents cleared and shapes the landscape. The rest have been caused by human influences - settlement, technical agriculture, extensive land use and labor migration into the foreland. After the closure of the few volcanic quarries that existed, their traces have also been blurred by vegetation, decay or filling. The drainage properties of the Schlottuffe have become unimportant for the settlements of the karstified Swabian Alb since the area-wide Alb water supply from 1870. In the foothills of the Alb, the volcanic rock often forms domed or conical elevations because the layers of the Middle Jurassic are less resistant to weathering and erosion than the tuff chimney . Vineyards and orchards are often found on the sun-exposed slopes of these volcanic hardwoods .

Morphology in the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area

Geomorphologically, three types of landscape can be easily distinguished:

- On the Alb plateau, the Schopflocher Moor (a high moor dammed by volcanic rock ), the circular, drained Randecker Maar (it has already been severely cut through the erosive relocation of the Albtrauf), and numerous, mostly populated, terrain depressions shape the landscape.

Because the basin-like tops of the tuff chimneys, which are now worn away, are impermeable to water in contrast to the limestone in the area, villages were preferred to form in the basins, as small karst springs , wells or ponds helped to partially compensate for water shortages - for example in Apfelstetten , Auingen, Böhringen , Böttingen, Donnstetten, Dottingen, Erkenbrechtsweiler, Feldstetten , Grabenstetten , Groß- and Kleinengstingen, Gruorn, Hengen, Hülben, Laichingen, Magolsheim, Ochsenwang, Ohnastetten , Rietheim, Sirchingen, Upfingen , Wittlingen, Würtingen, or Zainingen. - The second largest and very well researched Jusi next to the Randecker Maar can be seen as a prime example of a volcanic mountain that is still partially connected to today's Alb plateau.

- The Limburg is the prime example of isolated mountains, which lie in the mittleren- or Lower Jurassic of the Alb foothills. The named objects are also very well known because of their easily comprehensible volcanic shapes.

Mountains of witnesses , close to the eaves, but isolated, or as the spur of the eaves, are often misinterpreted as clear witnesses to the Swabian geological history. Jusi, Limburg, Floriansberg, Aichel- and Turmberg, Georgenberg and others are just pseudo-witness mountains! Reutlingen overlooks two similar cone mountains, Georgenberg and Achalm - but without a doubt only the former is of volcanic origin. In the middle Jurassic, which dominates the Alb foreland, the Schlottuff rock often appears as a hard rock, whose fertile soils also protrude biologically / ecologically effective in the debris - similar to the Alb eaves. The Calverbühl near Dettingen an der Erms , which rises from the sediments of Central Jurassic, can be cited as an example of a volcanic hardy .

volcanology

Text sources

There is an abundance of publications dealing with volcanic phenomena in the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area. Four authors have dealt extensively with the subject. In 1894/5 Wilhelm Branco identified “Swabia's 125 volcanic embryos”. He had explored the area on extensive foot excursions. Rock samples from his collection were later stored in the Institute for Mineralogy of the University of Tübingen and are transferred to the geoscientific collection. These include many samples of outcrops that have not existed in the area for many decades. In 1941 Hans Cloos introduced the term "Swabian volcano" into geoscientific literature on the basis of numerous field observations. In 1969 the geophysicist Otto Mäussnest published that he could confirm 335 eruption points through his research carried out from 1953 to 1968. Mäussnest's gravimetric and geomagnetic measurements almost doubled the number of sites (356 eruption points were known in 2015). In 1982 the volcanologist Volker Lorenz revised assumptions about the Swabian volcano by classifying its volcanism as a “phreatomagmatic type of eruption”. During this time it was recognized that the force of the explosion did not come from a gas- lapilli mixture, but from water vapor explosions as soon as hot Schlottuff reached water-bearing layers. Lorenz derived the hydrogeological conditions of the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area from the numerous findings of the Jura karstologists and made them useful for his eruption thesis by making the analogy to the phreatomagmatic volcanic type of other volcanic areas.

The volcanic activities were determined by the radiometric age dating (K / Ar age) of Lippolt et al. 1973 to 17-11 million years BC u. Z. dated to the Miocene , which “is also in line with the biostratigraphic age of the fossil-bearing maar sediments ( zones MN5 to MN8 )”. For volcanic rocks from the Hohenbol, Lippolt et al. an age of 11 million years.

Classification in worldwide volcanism

Cloos , who had found several good information at the time, had examined the Jusi and other eruption points in detail and found that all of the eruption points could be described as the one "Swabian volcano". Today it is assumed that the " intraplate volcanism " of the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area developed over a mantle diapir .

In 1982, Lorenz said that better than the term “Swabian volcano” introduced by Cloos in 1941 would be the term “Urach-Kirchheimer volcanic area”, because the center of the eruption points coincides with the geological trough “Uracher Mulde”. The trough is interpreted as an older basement structure. This regional geological feature is the actual unique selling point, since almost all volcanoes of the Urach-Kirchheimer volcanic area belong to the “ phreatomagmatic eruption ” type . This type can also be found in other volcanic areas: Vulkaneifel , Hegau , Midland Valley , Scotland, kimberlite , South Africa, USA, Australia.

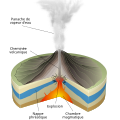

Origin and development of the Swabian volcano

The volcanic dikes developed along deep, tectonically broken fissures and crevices, ie preferably in tectonic weak zones (valleys and karst fissures). The paths widened to almost vertical corridors and breakthroughs. The chimneys have diameters between a few tens of meters and 1.2 kilometers. On a world scale, they are therefore to be classified as small. The tuffs consist mainly of mostly very small lapilli, with a crystalline core of olivine or melilite , or both ( minerals ), surrounded by a glass skin.

The first volcanic activities are likely to have proceeded similarly in many cases: more or less numerous individual eruptions per vent, lasting several days to months. Deposition of ejecta as a crater wall and laterally over a few kilometers, also some volcanic bombs . There was no lava deposit. The traces on the surfaces have long been removed. The juvenile pyroclasts in the chimneys - ash, lapilli - and angular as well as rounded xenolites have compacted and sagged over time (origin of the xenolites: upper mantle , Variscan basement , Mesozoic overburden ). Today there are thin Jura cover layers over most chimneys and mostly thin, nutrient-poor weathered coverings on which many plant communities well adapted to these conditions have settled: species-rich pasture grasses, rare, valuable flowers such as B. Orchids. On the Alb part of the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area, extensive beech forests are characteristic today.

When the (ground) water-bearing layers penetrated, violent steam explosions occurred which formed funnels. In the process, part of the tuff fell back into the chimney openings together with debris from the breached Jura cover layers, and the funnel fillings sagged as a result of the tuff degassing. Water-filled maars formed in the upper, unfilled parts of the funnels . In later eruptions, chimneys widened and led to further steam explosions until the water was used up everywhere. After the very long process of erosion, weathering, sedimentation and compaction can be found today Tuffite into the vent residues in stratified and unstratified form (pyroclastic and non-pyroclastic). The remains are still found today.

In the case of the two pseudo-witness mountains Jusi and Aichelberg , Cloos found up to 300 m large "sinking clods" from no longer existing stratigraphically higher Jura layers in the Schlottuff, which were more or less shattered, but still preserved in their original layer structure. Lorenz , however, rejected the mechanical genesis of these sinking clods as claimed by Cloos - they slowly "detached themselves from their original rock compound" and then slowly sank in the "rising gas-ash / lapilli flow" - as untenable. Because of their enormous size, these clods rather broke out in caldera-like extensions of the initial conveyor chimneys and then sagged with them.

Only in a few volcanic vents did magma melt intruded in replenishments in narrow channels up to the current outcrop areas of the tuffs. Cloos describes an intrusion in Jusi. The intrusions contain many different minerals, including a. also olivine and melilite. 22 eruption points with massive olivine meliliths are shown on the geo-map.

The originally postulated connection between the heat anomaly and the volcanism of the Urach-Kirchheimer area (thermal baths of Beuren and Bad Urach ) must be "traced back to other causes in the more recent geological past."

Significant single volcanoes

The volcanic vent near Scharnhausen (9 km southeast of Stuttgart), the northernmost outpost of the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area in the foothills of the Alb, lies at 310 m above sea level. NHN . It is the most heavily eroded volcanic vent at around 700 m from today's Alb plateau and the only one in the pre-Jurassic Keuper where the Upper, Middle and Lower Jura have been eroded. A little later, Branco made sure with a 7 m drill hole , which was important for the geology of Baden-Württemberg : "... a poor little outcrop in which the owner of volcanic tuff is being dug" actually contains Jurassic fragments "up to the White Jura beta. ”This provided proof that“ the Alb at that time extended at least as far as the Stuttgart area. ”The Weißjurafund also provided“ for the first time a relative standard, even if only for the minimum amount, ”that the“ The northern edge of the Alb has receded at least about 23 kilometers to the south ”. In the geographic map 7221 Stuttgart-Südost, edition from 1960, the volcanic vent is entered with a diameter of approx. 60 m.

Recognizable as a volcano

Some volcanic forms are still clearly recognizable today and are therefore generally known. These include the Randecker Maar (Mäussnest: ~ 1.2 km, NSG), the Schopflocher Moor (Mäussnest: ~ 500 m, NSG) and Limburg (Müssnest: ~ 500 × 750 m, NSG). Also shape the landscape are Molach (Mäussnest: ~ 220 x 350 m), Konrad rock (Mäussnest: ~ 120 x 150 m), Schlottuff and smoothly troubled Jura wall of a small volcano at the Neuffener platforms (designation at Mäussnest "Wendeberg" ~ 150 m. Entered on the geo map with ~ 100 m) and the Hohenbol cone mountain adjacent to the Teckberg (Mäussnest: ~ 420 × 550 m, NSG) near Owen . Right next to the Hohenbol is the Götzenbrühl , where olivine melilithite was also mined in the past.

The two small eruption points Wendenberg and Konradfels on the western and eastern steep slopes of the Erkenbrechtsweiler peninsula are geological objects of interest. At the edge of the Wendenbergschlotes it is almost exemplary how the formerly hot tuff mass has penetrated the banked Weißjura (lower rock limestone formation, ki2, Malm delta), completely smooth-edged. Due to the erosion of the Lenninger Lauter valley , the compacted, caked chimney content of the Konradfelsen is completely exposed as a hard chimney needle for many meters.

The Jusi chimney (Mäussnest: ~ 1000 m, NSG) is the second largest in the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area after that of the Randecker Maar. A much used steep path leads to the treeless viewing platform ( 673 m above sea level ) of the overhang, which protrudes over 4 km (sic!) Into the foothills of the Alb. The spur is legally protected on the narrow side of the Dettinger Ermstal as a large nature reserve Jusi - Auf dem Berg .

Volcanoes of the Alb plateau

Numerous depressions in the terrain can be seen on the relatively flat Alb plateau, which are interpreted as relatively well-preserved remains of volcanic maar funnels. In contrast to the Alb foreland, the Schlottops were only eroded by a maximum of 200 m on the plateau. As far as the funnel-like depressions have not been completely settled, the water-retaining pyroclasts have received wetlands (e.g. the Molach biotope ) or hulls (e.g. the one in the village of Zainingen , volcano near Mäussnest: ~ 650 × 370 m). Numerous populated depressions (e.g. Donnstetten , volcano near Mäussnest: ~ 630 m) alleviated the earlier water shortage in the Albdörfer by using small karst springs or shells, or by drilling wells.

Geophysical exceptional phenomena

The chimneys contain minerals that have pronounced magnetic properties. This results in magnetic anomalies in relation to the geomagnetism that is present on all sides . In the summit area of the Konradfels and the small Kegelberg Calver Bühl (Mäussnest: ~ 120m), which protrudes from the Middle Jurassic layers , west of Dettingen an der Erms , particularly strong magnetizations were found, which are interpreted as lightning magnetization . Magnetic needles of normal compasses are strongly deflected here. Only in very few cases are volcanic rocks from chimneys still visible on surfaces today; Only with the highly sensitive geophysical measurement methods implemented by Mäussnest for the first time could many new chimneys be found and the finds more than doubled.

At the eruption points Eisenrüttel (NW Dottingen (Münsingen) , Mäussnest: ~ 800 × 500 m, NSG Höhnriß-Neuben) and Sternberg (near Gomadingen , Mäussnest: ~ 40 m) massive basalt eruptions have always been assumed. At the Eisenrüttel, basalt was mined from 1867 to 1900 and processed into road gravel in the Georgenau state basalt crushing plant. Wetlands have developed in the former quarries. In 2009, several different geophysical measuring methods (geomagnetics, geoelectrics ) were able to prove that the Sternberg is an “effusive melilithic volcanism”, the volcanic rocks of which are probably “remains of a fossil lava lake”. It is assumed that massive olivine melilites emerged in a second phase after phreatomagmatic, funnel-forming eruptions. The basalt chimney was calculated to have a maximum diameter of 45–50 m. The volcanic rocks of Sternberg's an age of ~ 16 million years ago. The Sternberg is one of the few eruption points on the Alb plateau that have not remained as terrain depressions. The volcano towers as Härtling with approx. 844 m above sea level. NHN the peaks of the area. Perhaps the former Miocene land surface in the area of the Sternberg has been only a few meters deeper until today.

At Grabenstetten there is an exposed basalt corridor (approx. 1500 m long, 1 m wide) that has no volcanic vent character. Today no further corridors are open in the volcanic area.

Böttinger marble

A special rarity in geological, mineralogical and paleontological terms, probably even something unique, was created in the Böttinger Eruptionskulde (Mäussnest: ~ 500 × 550 m) east of Münsingen. The rising thermal water of a large crevice at the eruption funnel layered alternately white and strongly ferrous (red) sintered lime, so that in the approx. 200 × 30 m long crevice large amounts of so-called “banded Böttinger marble ” and - less valuable - “wild” Marble ”. The vertical rock layers that are decisive for the banding are still clearly visible today. The Böttinger marble is not a real marble in the petrographic sense, but a thermal sintered lime ( travertine ). From the quarry in the crevice, slabs have been extracted since 1763, which were sawn and polished to form the dominant, magnificent paneling of the large “marble hall” of the “New Stuttgart Palace”. After the castle was destroyed in the World War I a. the marble hall was rebuilt from 1955 with freshly broken Böttinger marble. A similar, but less well-known example is the red quarry near Riedöschingen in the Urach volcanic area a little further south.

"Banded Böttinger marble ", polishable sinter plates from the volcanic crevice

Profile "Swabian volcano", plateau and Alb foreland

Melilite and olivine in thin section , lava on the volcanic island of Oahu (Hawaii)

phreatomagmatic volcano, scheme

Classic maar area Vulkaneifel

Sternberg volcano near Gomadingen , slightly bushy juniper heather on the southern slope

Calver Bühl , strongly magnetized volcanic vent on the slope of the Erms near Dettingen

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Johannes Baier: The Urach-Kirchheimer volcanic area of the Swabian Alb. In: The opening. Jhrg. 71, No. 4, 2020, pp. 224–233.

- ^ A b c Otto F. Geyer, Manfred Gwinner: Geology of Baden-Württemberg . Ed .: Matthias Geyer, Edgar Nitsch, Theo Simon. 5th completely revised edition. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-510-65267-9 , p. 338 f . (Geyer & Gwinner 2011).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 179 ( summary - Lorenz 1982).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 185 ( summary - Lorenz 1982).

- ↑ a b Johannes Baier: The Jusi near Metzingen - a volcanic vent on the Albrand . In: fossils . Journal of Earth History. 32nd year, no. 3 . Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim 2015, p. 40-45 (Baier 2015).

- ↑ a b c Johannes Baier, Günter Schweigert: The Calverbühl near Dettingen an der Erms . In: fossils . Journal of Earth History. 32nd year, no. 6 . Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim 2015, p. 56 ff . (Baier & Schweigert 2015).

- ↑ Mäussnest 1969a, p. 165

- ↑ Udo Neumann: The Miocene intraplate volcanism of the Urach volcanic area (excursion F on April 8, 1999) . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 81 , 1999, pp. 82 , doi : 10.1127 / jmogv / 81/1999/77 (Lorenz relied in particular on the fact that the quenched melts were of low viscosity (low in silica) and should have been low in gas due to the formation of little or no bubbles during the eruption.).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 180, 195 ( Summary - He derived the hydrogeological conditions of the Urach-Kirchheim volcanic area from the numerous findings of the Jurassic karstologists and made them useful for his eruption thesis by making the analogy to the phreatomagmatic volcano type of other German and international volcanic areas.) .

- ^ A b c Otto F. Geyer, Manfred Gwinner: Geology of Baden-Württemberg . Ed .: Matthias Geyer, Edgar Nitsch, Theo Simon. 5th completely revised edition. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-510-65267-9 , p. 328 (Geyer & Gwinner 2011).

- ^ Hans Cloos : Construction and activity of tuff chimneys. Investigations on the Swabian volcano . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 32 , no. 6-8 , 1941, pp. 710 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01801913 (Cloos 1941): “But they are so similar to each other and so different and spatially so sharply separated from the other volcanic structures in southern Germany that they can be seen as parts of a single large volcano with a peculiar structure, the 'Swabian volcano '(P. 770)> must consider. "

- ↑ Udo Neumann: The Miocene intraplate volcanism of the Urach volcanic area (excursion F on April 8, 1999) . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 81 , 1999, doi : 10.1127 / jmogv / 81/1999/77 (Neumann 1999).

- ↑ Manfred Gwinner : Tectonics, sedimentation and volcanism in the area of the "Uracher Mulde" (Swabian Alb, Württemberg) . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 43 , 1961, ISSN 0078-2947 , pp. 25-40 , doi : 10.1127 / jmogv / 43/1961/25 (Gwinner 1961).

- ^ A b Otto F. Geyer , Manfred Gwinner: Geology of Baden-Württemberg . 3. Edition. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-510-65126-9 , p. 330 ff . (Geyer & Gwinner 1986).

- ↑ a b Udo Neumann: The Miocene intraplate volcanism of the Urach volcanic area (excursion F on April 8, 1999) . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 81 , 1999, pp. 77 , doi : 10.1127 / jmogv / 81/1999/77 (Neumann 1999).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 180, 195 ( summary - Lorenz 1982).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 180, 195 ( summary - Lorenz 1982).

- ^ Otto F. Geyer , Manfred Gwinner: Geology of Baden-Württemberg . 3. Edition. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-510-65126-9 , p. 102 (Geyer & Gwinner 1986).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 185 ( summary - Lorenz 1982).

- ^ A b c Hans Cloos : Construction and activity of tuff chimneys. Investigations on the Swabian volcano . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 32 , no. 6-8 , 1941, pp. 709-800 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01801913 (Cloos 1941).

- ↑ Flat layer stratification, as it is found in the upper part of some tuff chimneys, is described by Lorenz as redistributed, epiclastic rocks, sediments, conglomerates or breccias, (Lorenz 1982), p. 180

- ^ Hans Cloos : Construction and activity of tuff chimneys. Investigations on the Swabian volcano . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 32 , no. 6-8 , 1941, pp. 736, 752 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01801913 (Cloos 1941).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 183 ( Summary - Because of their enormous size, the sinking clods must have broken out in caldera-like extensions of the initial conveyor chimneys and sagged with them.).

- ↑ Otto Mäussnest (arrangement): Map of the volcanic occurrences of the Middle Swabian Alb and its foreland . 1: 100,000. Ed .: State Surveying Office Baden-Württemberg. Land surveying office Baden-Württemberg, Freiburg 1978 (Mäussnest 1978).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982, pp. 185 ( Summary - Lorenz 1982 also sees these intrusions; he sees “the largest olivine-melilithite deposit in terms of area on the Eisenrüttel”, p. 192.).

- ↑ Wilhelm von Branco : A new tertiary volcano near Stuttgart, at the same time proof that the Alb once extended to the state capital . Armbruster & Riecker, Tübingen 1892, p. 3 (Branco 1892).

- ^ Otto F. Geyer, Manfred Gwinner: Geology of Baden-Württemberg . Ed .: Matthias Geyer, Edgar Nitsch, Theo Simon. 5th completely revised edition. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-510-65267-9 , p. 313 (Geyer & Gwinner confirm this again).

- ↑ a b Wilhelm von Branco : A new tertiary volcano near Stuttgart, at the same time proof that the Alb once extended to the state capital . Armbruster & Riecker, Tübingen 1892, p. 48, 50 (Branco 1892).

- ↑ Only the distinctive White Jurassic steps to the plateau have always been regarded as "Alb".

- ↑ The geophysical measurements of Mäussnest are in the geo maps in many cases with extended or deviating areas, or as completely new determinations.

- ↑ Johannes Baier: Hohenbol and Götzenbrühl - two volcanic vents at the foot of the Teck . In: fossils . Journal of Earth History. 33rd volume, no. 1 . Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim 2016, p. 38 ff . (Baier 2016).

- ↑ 1,192 Jusi-Auf dem Berg. Appreciation. 1992, accessed on November 17, 2017 (Jusi nature reserve).

- ↑ Otto Mäussnest: Magnetic investigations in the area of the Swabian volcano . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 58 , no. 2 , 1969, ISSN 1437-3254 , pp. 515 (Mäussnest 1969b).

- ↑ Fritz Scheerer: From the Swabian volcano . In: Local history sheets Balingen . No. 2 + 3 . Balingen 1983, p. 392-395 ( PDF - Scheerer 1983).

- ↑ Jörg Kröchert, Elmar Buchner, Martin Schmieder, Holger Maurer, Anette Strasser, Marcel Strasser: Effusive melilithic volcanism on the Swabian Alb - the Sternberg near Gomadingen . In: Journal of the German Society for Geosciences . tape 160 , no. 4 , 2009, p. 315-323 (Kröchert et al. 2009).

- ↑ Volker Lorenz : On the volcanology of the tuff chimneys of the Swabian Alb . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 64 , April 13, 1982 ( abstract ).

- ↑ Jörg Kröchert, Elmar Buchner, Martin Schmieder, Holger Maurer, Anette Strasser, Marcel Strasser: Effusive melilithic volcanism on the Swabian Alb - the Sternberg near Gomadingen . In: Journal of the German Society for Geosciences . tape 160 , no. 4 , 2009, p. 321 (Kröchert et al. 2009).

- ↑ Jörg Kröchert, Elmar Buchner, Martin Schmieder, Holger Maurer, Anette Strasser, Marcel Strasser: Effusive melilithic volcanism on the Swabian Alb - the Sternberg near Gomadingen . In: Journal of the German Society for Geosciences . tape 160 , no. 4 , 2009, p. 318 (Kröchert et al. 2009).

- ^ HJ Lippolt, W. Todt, I. Baranyi: K-Ar ages of basaltic rocks from the Urach volcanic district, SW Germany . In: Advances in Mineralogy . No. 50 , 1973, pp. 101-102 (Lippolt et al. 1973).

- ↑ Wolfgang Ufrecht: A sealed cave ruin stage on the Kuppenalb between Fehla and Lauchert ( Zollernalbkreis , Swabian Alb) . In: Laichinger Höhlenfreund . No. 41 , 2009, p. 39–60 (quoted from (Kröchert 2009), p. 316).

- ↑ Thomas Aigner: The Upper Miocene thermal sintered limestone from Böttingen ("Böttinger marble") on the Swabian Alb . In: The opening . No. 26 , 1975, p. 1 ( online [PDF] Aigner 1975).

- ^ Frank Thomas Lang: Local marble for a castle in Württemberg . In: Wilfried Rosendahl, Matthias Lopez Correa, Christoph Gruner (eds.): The Böttinger marble: colorful rock from hot springs . 2nd, revised edition. Pfeil, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-89937-168-0 , p. 34-41 (Lang 2003).

literature

- Wilhelm von Branco : A new tertiary volcano near Stuttgart, at the same time proof that the Alb once extended to the state capital . Armbruster & Riecker, Tübingen 1892 (Branco 1892).

- Wilhelm von Branco: Swabia's 125 volcanic embryos and their tuff-filled eruption tubes; the largest maar area on earth. Part I. In: Annuals of the Association for Patriotic Natural History in Württemberg . tape 50 , 1894, pp. 505-997 ( online [PDF] Branco 1894).

- Wilhelm von Branco: Swabia's 125 volcanic embryos and their tuff-filled eruption tubes; the largest maar area on earth. Part II. The nature of the formation of the tuffs and basalts, as well as the erosion series of the maars in the Urach area. General information about tuffs and maars . In: Annual books of the Association for Patriotic Natural History in Württemberg . tape 51 , 1895, p. 1–337 ( online [PDF] Branco 1895).

- Manfred Bräuhäuser , Manfred Frank : Explanations of the special geological map of Württemberg, sheet Stuttgart, No. 70 and sheet Möhringen, No. 69 . Ed .: Württemberg State Statistical Office. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1932.

- Hans Cloos : Construction and activity of tuff chimneys. Investigations on the Swabian volcano . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 32 , no. 6-8 , 1941, pp. 709-800 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01801913 (Cloos 1941).

- Manfred Frank: Geological map 1: 25000 of Baden-Württemberg . Explanations for sheet 7221 Stuttgart Southeast. Ed .: State Office for Geology, Raw Materials and Mining Baden-Württemberg . II edition. Land surveying office Baden-Württemberg, Freiburg 1960 (LGRB 1960).

- Otto Mäussnest : The results of the magnetic processing of the Swabian volcano . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 51 , 1969, ISSN 0078-2947 , pp. 159–167 , doi : 10.1127 / jmogv / 51/1969/159 (Mäussnest 1969a).

- Otto Mäussnest: Magnetic investigations in the area of the Swabian volcano . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 58 , no. 2 , 1969, ISSN 1437-3254 , pp. 512-520 (Mäussnest 1969b).

- Otto Mäussnest: The eruption points of the Swabian volcano . Part II. In: Journal of the German Geological Society . tape 125 , no. 51 , 1974, p. 23-54 (Mäussnest 1974).

- Udo Neumann: The Miocene intraplate volcanism of the Urach volcanic area (excursion F on April 8, 1999) . In: Annual reports and communications of the Upper Rhine Geological Association, N. F. Volume 81 , 1999, doi : 10.1127 / jmogv / 81/1999/77 (Neumann 1999).

- W. Roser, J. Mauch: The Swabian volcano. Geotopes and biotopes of the volcano b. Excursions with suggested routes . GO Druck Media Verlag, Kirchheim 2003 (Roser 2003).

- Wilfried Rosendahl, Matthias Lopez Correa, Christoph Gruner, Thilo Müller: The Böttinger marble: colorful rock from hot springs . Ed .: T. Müller. Staatsanzeiger, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-929981-48-3 (56 pages, Rosendahl et al. 2003).

- T Huth, B., Junker: Explanations for the geotouristic map of Baden-Württemberg 1: 200000 - North . Freiburg 2005 (LGRB 2005).

- Joachim Eberle, Bernhard Eitel, Wolf Dieter Blümel, Peter Wittmann: Germany's South from the Middle Ages to the present . Springer, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-662-54380-1 (Eberle et al. 2007).

- Wilfried Rosendahl, Baldur Junker, Andreas Megerle, Joachim Vogt (eds.): Swabian Alb (= walks in the history of the earth . No. 18 ). 2nd Edition. Pfeil, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-89937-065-2 (Rosendahl et al. 2008).

- W. Werner: Natural stone from Baden-Württemberg . Ed .: State Office for Geology, Raw Materials and Mining Baden-Württemberg. Freiburg 2013 (LGRB 2013).

- G. Schweigert: The Scharnhausen Volcano - an inventory 125 years after Branco's description . In: Annual books of the Society for Natural History in Württemberg . tape 174 , p. 191-207 .

- Johannes Baier: The Urach-Kirchheimer volcanic area of the Swabian Alb. In: The opening. Jhrg. 71, No. 4, 2020, pp. 224–233.

Web links

- Eberhard Lang, Pauritsch-Jacobi: 4,254 Höhnriß-Neuben. Appreciation. October 20, 1993, accessed on November 17, 2017 (Höhnriß-Neuben nature reserve (including Eisenrüttel volcano)).

Coordinates: 48 ° 30 '54.9 " N , 9 ° 25' 24.7" E