Storm height

Sturmhöhe (original title: Wuthering Heights [ ˈwʌðɘriŋ ˈhaits ]) is the only novel by the English writer Emily Brontë (1818–1848). Published in 1847 under the pseudonym Ellis Bell, the novel was largely rejected by Victorian audiences and is now considered a classic of 19th century British fiction .

action

The novel is set on the Wuthering Heights manor, managed by the Earnshaw family, on a windswept heights of the Yorkshire moors , and the more feudal, fertile valley manor, Thrushcross Grange, owned by the Linton family. The story of these two families is told over three generations.

The action is dominated by the foundling Heathcliff, whom old Earnshaw picked up on the streets of Liverpool when he was about six years old and raises with his own children Hindley and Catherine (Cathy). Housekeeper Ellen Dean, known as Nelly, becomes a mother substitute for Heathcliff. While she takes care of him, she initially rejects his alien nature, but over time accepts him.

After old Earnshaw dies, Heathcliff is bullied, degraded, and banished from the mansion to the stable by his stepbrother Hindley. Heathcliff, on the other hand, has a deep friendship with his stepsister Cathy. Cathy sees a kindred spirit in Heathcliff: Both are wild, passionate, strong-willed, uncompromising in their claims and are tyrannized by Hindley.

When his young wife dies of tuberculosis , Hindley becomes addicted to drinking and gambling and neglects his house and yard as well as his young son Hareton.

A few years later, the young Edgar Linton, the future heir to Thrushcross Grange, proposes marriage to Cathy, now sixteen. Cathy sees this marriage as an opportunity to escape the dire conditions on Wuthering Heights. When Heathcliff overhears Cathy saying to Nelly that a marriage to Heathcliff would dishonor her socially and that the luxury of Thrushcross Grange is preferable, although Edgar is indifferent to her, the offended boy runs away and leaves the area. The loss of her beloved foster brother and closest confidante plunges Cathy into a deep nervous crisis, which also manifests itself in a life-threatening fever. Worried Edgar Linton takes Cathy to the Grange, where they get married a few months later.

After three years, Heathcliff returns as a handsome and rich young man and tries to win Catherine over: he invades her marriage to Edgar, her old love for Heathcliff flares up again. But since she is pregnant by her husband, she is unwilling to give up marriage despite her disregard for bourgeois morality. Instead, she wants Heathcliff as a friend and confidante, whom Edgar should also accept. Heathcliff, however, desires Cathy for himself and in his resentment begins to take revenge on the Earnshaw and Linton families. First he marries Edgar's sister Isabella Linton against Edgar's wishes and abuses her in marriage. In the ensuing conflict between Edgar and Heathcliff, Catherine breaks up: she dies giving birth to her daughter Catherine.

The pregnant Isabella finally manages to escape to London, where her son is born: Linton, a sickly child. During this time, Heathcliff ruins the gambling and alcoholic stepbrother Hindley and takes possession of Wuthering Heights. He incites Hindley's little son Hareton against his father. After his sudden death in the alcohol delirium, Heathcliff brings Hareton up in revenge against Hindley in rural, uneducated circumstances. But he does not abuse the boy, as Hindley once did with himself, and Hareton develops great affection for his foster father.

After Isabella's death, Heathcliff takes his chronically ill and morose son Linton to live with him. Years later, he lures the now sixteen-year-old Catherine to Wuthering Heights to bring her together with Linton. Eventually, when her father Edgar falls ill with pneumonia , Heathcliff forces the girl into marriage to Linton. Edgar dies without being able to change his will, which Linton envisages as heir, for Catherine's protection. A short time later, Linton also dies. According to the law of inheritance in force at the time of the act, all property falls to the next male relative, Heathcliff.

Heathcliff is now master of both houses. Out of greed, he rents out Thrushcross Grange, which he actually wanted to have torn down in revenge, to a stranger: the young Lockwood. When Lockwood spends a night on Wuthering Heights on his first visit, he has a mysterious vision: the ghost of Catherine (Cathy) Earnshaw appears at the window and begs to be admitted. Heathcliff is shocked by Lockwood's report, which causes a sudden, drastic change in his personality. His energy is used up. He cannot or does not want to prevent Catherine from trying to form Haretons and from developing a love relationship between the two. After all, Heathcliff can no longer eat, drink or sleep from exhaustion. In the end, he falls into an unexplained rapture and dies one night in a state of ecstasy. The window by his bed is open.

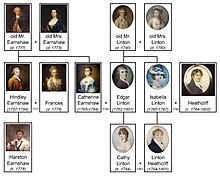

genealogy

Heathcliff and the Earnshaw and Linton families

| Wuthering Heights | Thrushcross Grange | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mr. Earnshaw † Oct. 1777 |

Mrs. Earnshaw † Spring 1773 |

Mr. Linton † Fall 1780 |

Mrs. Linton † Fall 1780 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⚭1783 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frances † 1778 |

Hindley * summer 1757 † Sept. 1784 |

Catherine * summer 1765 † 20. March 1784 |

Edgar * 1762 † Sept. 1801 |

Isabella * 1765 † July 1797 |

Heathcliff * 1764 † April 1802 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⚭1803 | ⚭1801 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hareton * June 1778 |

Catherine * March 1784 |

Linton * Sept. 1784 † Sept. 1801 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Narrative structure

teller

The event is essentially presented by two first-person narrators . The first narrator is Lockwood, who leased Thrushcross Grange from Heathcliff. He is a young gentleman, a loner and at the same time an educated city dweller who seeks peace and quiet in the country. He takes no personal interest in what is happening and observes the situation from the outside, but with a keen eye, like a tourist the wild locals, with irony, but also self-irony. Lockwood's presentation is similar to a journal entry. He starts twice, in 1801 and 1802, at the beginning and at the end, and thereby gives the novel a certain framework.

Lockwood's account of his own experiences in Yorkshire is more of a snapshot. From his landlady in Thrushcross Grange, Ellen Dean, he tells the dramatic story of Catherine and Heathcliff. Nelly Dean has been an eyewitness from the beginning, as a long-time housekeeper in both families, she has intimate knowledge of everyone involved and is at the same time a confidante for everyone. She is not personally involved in the cruel events and tries again and again to act soothingly and attenuating the people and the events through spying, manipulation, well-intentioned intrigues and admonitions, but in vain. In between, she lets most of the main characters have their say in the form of a first-person narration. Nelly appears to be the main narrator, but, strictly speaking, readers receive a report, already edited by Lockwood, of what Mrs. Dean told him. This shift allows the narrator to distance himself even further from what is actually happening.

This narrative form with two first-person narrators and the narration of the narrated acts like a double window through which the reader looks at the events, which are sometimes difficult to interpret. The author disappears behind it completely and leaves the reader to their own devices. This very modern novel design, which was completely unusual at the time, was certainly confusing for a Victorian audience. Emily Brontë does not give a clear moral assessment at any point, but remains ambivalent, she leaves the formation of opinion to the reader. The author must by no means be equated with the narrator Nelly Dean, whose interpretations and evaluations are mostly obvious to the reader, but also sometimes seem questionable, just as her attempts to exert influence are completely overwhelmed by the force of the dramatic events.

construction

The novel begins with Lockwood's experiences as the plot is nearing its conclusion. With Lockwood in Wuthering Heights, the reader experiences an atmosphere of distrust, tension and irritability everywhere and asks himself how it came about, what relationship the people are with one another and what end is to be expected. This is followed by a long retrospective look through Nelly Dean's narration of the events of the past. When Lockwood re-enters the plot at the end, the tension has been released and Nelly Dean can tell how it came to a happy ending .

Despite the nested structure, the author manages to preserve the inner logic of the novel. The narration is coherent down to the seemingly trivial: When Hindley drops little Hareton while drunk, Heathcliff catches the boy in reflex. Later, it is Heathcliff who unwittingly saves Wuthering Heights for Hareton and thus saves the young man from poverty. (Without Heathcliff's vengeance, Hindley's property would have passed to foreign creditors). Mr. Lockwood mentions at the beginning that the boggy earth of Gimmerton keeps the corpses buried in the cemetery "mummy-like". At the end of the novel, Heathcliff opens Cathy's grave and tells Nelly Dean that Cathy's face is still "still her face".

Timeline

| 1500: | The stone above the front door of Wuthering Heights, named Hareton Earnshaw, is inscribed, possibly to document the completion of the house |

| 1757: | Summer: Hindley Earnshaw is born |

| 1762: | Edgar Linton is born |

| 1765: | Summer: Catherine Earnshaw is born; Late year: Isabella Linton is born |

| 1771: | Late summer: Mr. Earnshaw brings Heathcliff to Wuthering Heights |

| 1773: | Spring: Mrs. Earnshaw dies |

| 1774: | Hindley is sent to college |

| 1775: | October: Hindley marries Frances; Mr. Earnshaw dies and Hindley returns;

November: Heathcliff and Catherine visit Thrushcross Grange for the first time; Catherine will stay there until Christmas |

| 1778: | June: Hareton is born; Frances dies |

| 1780: | Heathcliff flees Wuthering Hights; Mr. and Mrs. Linton are dying |

| 1783: | March: Catherine is married to Edgar; September: Heathcliff returns |

| 1784: | February: Heathcliff marries Isabella; March 20: Catherine dies and Cathy is born; September: Hindley dies; Linton Heathcliff is born |

| 1797: | Isabella dies; Cathy visits Wuthering Heights and meets Hareton; Linton is taken to Thrushcross Grange and then to Wuthering Heights |

| 1800: | March 20: Cathy meets Heathcliff and sees Linton again |

| 1801: | August: Cathy and Linton get married; Edgar dies;

September: Linton dies; Mr. Lockwood goes to Thrushcross Grange and visits Wuthering Heights, this is where his story begins |

| 1802: | January: Mr. Lockwood returns to London; April: Heathcliff dies; September: Mr. Lockwood returns to Thrushcross Grange |

| 1803: | New Year: Cathy plans to marry Hareton |

characters

- Heathcliff (around 1764–1802): Presumably an orphan, he is found by Mr. Earnshaw on the streets of Liverpool and taken to Wuthering Heights. There he is reluctantly received and looked after by the family. He and Catherine get closer, and their love becomes the main theme of the first volume. His revenge on the man she chooses to marry, and the consequences of that vengeance, are the main theme of the second volume. Heathcliff has been considered a Byronian hero , but critics point out that he is reinventing himself in various places, making it difficult to assign his character to any particular type. Due to his ambiguous position in society and his status deficit - underlined by the fact that "Heathcliff" is his nickname; he has no surname - he was a favorite subject of Marxist literary criticism.

- Catherine Earnshaw (1765–1784): She is first introduced to the reader after her death, through Lockwood's discovery of her diary and drawings. The description of her life can be found almost exclusively in the first volume. She seems unsure whether she is more like Heathcliff or would like to be like him, or whether she feels more like Edgar. It seems that she wants both, that she cannot be fully herself without both, but society or human nature does not allow it. Some critics have argued that their decision to marry Edgar was an allegorical rejection of nature and a surrender to culture - a decision with fateful consequences for everyone else. Her character has also been interpreted according to feminist and psychoanalytic literary theory.

- Edgar Linton (1762–1801): Introduced as a child of the Linton family, he lives on Thrushcross Grange. His behavior and manners stand in sharp contrast with Heathcliff, who immediately displeases him, and Catherine, who is drawn to him. She marries him instead of Heathcliffs because of his higher social status. From the perspective of the feminist interpretation, this makes clear the problem of a social order in which women can only gain reputation and economic security through marriage.

- Nelly Dean (* around 1755): The main narrator of the novel. She has been a domestic servant for three generations of the Earnshaws and two generations of the Lintons. In a certain sense, it bridges the gap between nature and culture. Of low origin, she still considers herself to be Hindley's milk sister (they are of the same age and their mother is Hindley's wet nurse). She lives and works among the rugged residents of Sturmhöhe, but is well-read and also internalizes the refined manners of Thrushcross Grange. Her nickname Ellen is used to maintain a respectful distance - she is only called Nelly by loved ones. She acts as an impartial narrator, although her close relationship with the main characters often means that she is actively involved in many processes herself. Critics have often discussed how far their actions as those of a minor character really affect the other characters.

- Isabella Linton (1765–1797): Introduced as a member of the Linton family, Isabella is only shown in relation to other characters. She sees Heathcliff romantically, although Catherine warns her not to, and becomes an unsuspecting witness to his plans for revenge against Edgar. Heathcliff marries her but mistreats her. After her pregnancy, she flees to London and gives birth to a son, Linton. She flees from her husband's abuse, which leads some critics - especially feminist interpreters - to view her as the real tragic-romantic heroine of the novel in the traditional sense.

- Hindley Earnshaw (1757–1784): Catherine's older brother, who detested Heathcliff at first glance and humiliated him throughout childhood. He is sent off to school because of his bad behavior, but returns to Wuthering Heights with his new wife Frances after the death of his father. His hatred of Heathcliff has only intensified. After Frances passed away, Hindley sank into alcohol, depression and debt. In doing so, he ruins the Earnshaw family. Shortly before his death, Hindley tries to shoot his archenemy Heathcliff, but is beaten up by him.

- Hareton Earnshaw (* 1778): He is the son of Hindley and Frances and became an orphan after a few years. After being raised primarily by Nelly, Heathcliff took over the upbringing after Hindley's death. Heathcliff then contains Hareton of any form of education or upbringing. As an adult, Hareton lives on Wuthering Heights as a kind of servant, looking awkward and apparently ignorant that he should be the real master of Wuthering Heights. Only after Heathcliff's death, at the end of the novel, can Hareton slowly develop his own self-confidence and steer towards a marriage with Cathy Linton.

- Cathy Linton (* 1784): She is the daughter of Catherine Earnshaw and Edgar Linton, she is intelligent and sweet, but can also be headstrong like her mother. Cathy is left unclear by her cautious father about the history of her birth and thus also about Heathcliff. But as she gets older, she feels more and more attracted to Wuthering Heights. Due to the intrigues of Heathcliff, she marries her cousin Linton and from then on has to live very bitterly on Wuthering Heights, where she is harassed by Heathcliff. At the end of the novel, her wedding to Hareton is about to begin.

- Linton Heathcliff (1784-1801): He is the feeble son of Heathcliff and Isabella. After his mother fled Heathcliff, he spent his childhood with her in the south of England. After his mother dies when he is twelve, he comes to Wuthering Heights. He is selfish, can be cruel, and repeatedly uses his poor health as an excuse to achieve goals. Although he doesn't love Cathy, and neither does she love him, father Heathcliff forces him into marriage to Cathy (so that Heathcliff can also get control of the Lintons' estate). Soon after the wedding, Linton dies of illness.

- Joseph : The quirky servant from Wuthering Heights who, at the end of the novel, has served there for over 60 years. He's a strict, self-righteous Christian who gives sermons to the people of Wuthering Heights every Sunday. He speaks with a heavy Yorkshire accent and can hardly say a good word about the other characters in the novel.

- Mr Lockwood : The young, well-to-do first-person narrator who rented Thrushcross Grange in 1801. He is disappointed and tired of the hustle and bustle of the city, which is why he settles in this remote Yorkshire area. But he realizes in the course of the novel that this inhospitable area with its gloomy inhabitants is not for him. He soon says goodbye to Thrushcross Grange.

- Frances († 1778): Hindley's ailing wife and Hareton's mother. She is described as quite simple-minded and apparently comes from a very simple background.

- Mr. Earnshaw († 1777) and Mrs. Earnshaw († 1773): Catherine and Hindley's parents. At the beginning of Nelly's story, Earnshaw is Lord of Wuthering Heights, he is described as spirited but loving. He is strangely infatuated with his adopted son, Heathcliff, which begins the dispute on Wuthering Heights. His wife, who almost dies at the beginning of the story, immediately distrusts the childish Heathcliff.

- Mr. and Mrs. Linton (both † 1780 with the same disease): Edgar and Isabella's parents who raise their children in a cultivated way despite the rural area. Mr. Linton is (like his son later) head of the village of Gimmerton.

- Dr. Kenneth : Gimmerton's long-time doctor, a friend of Hindley's, who is present at the novel's illnesses.

- Zillah : A maid on Wuthering Heights at the time the narrator Mr. Lockwood arrives. She is actually good-natured, for example in dealing with Lockwood, but does not want to mess with Heathcliff either. So she doesn't help Cathy either.

- Mr. Green : Edgar's corrupt attorney who was supposed to change his will and prevent Thrushcross Grange from falling to Heathcliff. But Mr. Green changes sides and supports Heathcliff after Edgar's death.

interpretation

General

The novel is now considered a classic work of English fiction. Since it was first published in 1848, the novel has had a variety of interpretations. It is neither in the tradition of the historical novel by Walter Scott nor in that of the strictly realistic and socially oriented novel such as Jane Austen , but is a work of its own. The modern-looking narrative technique reminiscent of Joseph Conrad refers to the 20th century.

The opposing interpretations mostly focus on the main character of the novel: Heathcliff. The first critics have long wanted to see him as a monster or a satanic character, and this seems justified by his actions. Another, socially critical interpretation sees Heathcliff, the foundling from the Liverpool slums, an avenger of the underprivileged and a social rebel against capitalist society and the oppression of the worker by the ruling class, who then slips into the role of the oppressor himself. As an internally torn and intelligent antihero who puts personal goals above general morals, Heathcliff is widely regarded as a classic example of the Byronian hero in English literature.

Nature mystical interpretation

Heathcliff's character and actions are shaped by opposites and contradictions. He is a foundling and stranger of unknown origin from the slums of Liverpool. In the Brontë interpretation, there are various theses about Heathcliff's possible ancestry that Emily Brontë could have had in mind: a gypsy child abandoned, the abandoned son of a prostitute, a child of Irish emigrants whose parents died before leaving for America, an illegitimate child of old earnshaw. At the same time, it appears like a natural element of the wild moorland of remote Yorkshire ( Heathcliff means heather cliff ). In the 20th century, a predominant reading of the novel emerged that sees Heathcliff not only as an individual, but also as the embodiment of elementary forces of nature, just like Wuthering Heights, with whom Heathcliff forms a unity in the novel.

This is how Lockwood experiences him on his visit to Wuthering Heights when Heathcliff's pack of dogs pounces on him. Nelly Dean says of Heathcliff that he was as pious as a lamb as a child, he endured the harassment of Hindley stoically, but the grown and transformed Heathcliff is terrifyingly brutal and callous, even against his own son and the relatives he tortures , cheats and in part drives them to death. In the description of Nelly Dean, who shows a certain sympathy for him, he appears not only as a perpetrator and tormentor, but increasingly as a victim and hunted by an invisible power. He transforms himself several times in the course of the story, most surprisingly at the end, where, it seems, he goes to death in a state of ecstasy.

As a young girl, Cathy said to Nelly Dean: "I am Heathcliff". There is an indestructible unity between her and Heathcliff, they both believe, and in this unity lies perhaps the key to understanding the novel. This relationship is not portrayed as sexual, it grew out of the kinship of the wild children in sharing the untamed nature of Wuthering Heights, fighting together against Hindley's oppression, and disdain for the refined way of life on Thrushcross Grange. Through her marriage to Edgar and the derogatory words about Heathcliff, Cathy has committed treason and torn this bond, thus violating an eternal law of nature.

Heathcliff's terrible revenge on the Earnshaw and Linton families after the death of Cathy is therefore not simply the personal revenge of an injured person, but a disaster that arises from the violation of the natural order. In the end, Heathcliff always appears more as the hunted and hunted, the late Cathy determines his actions as a noticeable but invisible ghost. He tells Nelly Dean (Chapter 29) that these appearances do not arise from his imagination, but - in the sense of the fictional reality of the novel - are "real". The experiences are testified by the rationalist Lockwood (Chapter 3).

The fact that Cathy's ghost appeared to a stranger who could even see her shook Heathcliff's previously indomitable spirit and broke his will to revenge. The penetration of the deceased in the living world both a subject of popular in England in the early 19th century Gothic novel ( Gothic novel ), and a typical element of the dramas of Shakespeare . At the same time, the mystical elements in this work point to the magical realism of the 20th century.

Heathcliff's change before his death fits this interpretation. The love between Hareton and the young Catherine reminds Heathcliff and the reader of his relationship with Cathy: It revives the harmonious unity that had been destroyed by Cathy's betrayal and, to a certain extent, soothes the spirits of revenge. It is possible to interpret that this also leads to a reconciliation with the spirit of the deceased Cathy. The open window by his bed and Heathcliff's triumphant, blissful expression in death indicate that he finally saw Cathy's ghost as she took his soul into the afterlife. Together with Edgar, Heathcliff finds his final resting place in the grave next to Cathy. The dead, says Nelly Dean in the novel, have come to rest.

Additional interpretative approaches

Modern interpretations complement this nature-mystical reading with a psychological interpretation of the inner conflicts and developments of the characters. Heathcliff in particular is not seen as a mere embodiment of the forces of nature, but also as a person who has been traumatized by his fate and his emotional predisposition, who lives out his psychological deficits in anti-social behavior because his closed, hard character does not allow him to deal with his wounds to show and to find help in interpersonal contacts.

This is how Heathcliff appears most humanly as a still vulnerable boy: In one scene he complains to Nelly Dean of his grief of being just a poor, filthy foundling; in another, he confesses to Nelly that he cannot eat because he is sick in pain from Hindley's brutal beatings. As an adult, Heathcliff seems to have shed that human side. He sometimes shows animal behavior: he growls, rages and roars with anger, even bares his teeth. Nelly describes the difference between Edgar's and Heathcliff's mourning for the dead Cathy as the difference between a decent and a wild person: while Edgar retreats into his house and quietly processes the loss, Heathcliff bangs his head against a tree in the garden and howls Despair and pain "like a wounded animal".

At the same time, Heathcliff's uncivilized and amoral mind is also his enigmatic strength: He uses his physical superiority and his willpower to obtain at least sadistic satisfaction in the course of revenge , if his manic love for Cathy has not been satisfied. However, Heathcliff does not have to be seen as a demon or devil as in the Victorian criticism , he is initially an egocentric, mentally ill person who lacks any insight into the emotional world of others, even his beloved Cathy.

Another interpretation also sees a similarity between Heathcliff and Shakespeare's character Macbeth : Both men develop into seemingly inhumanly cruel human traffickers in the course of the plot, both cling in manic love to an idealized woman to whom they are almost a slave, both are repeated through enigmatic visions tormented and finally can no longer sleep, both experience an ecstatic release at the end of their lives.

Historical background

What happens in the second part of the novel becomes more understandable if one takes into account the legal historical background that made Heathcliff's work possible. In the 19th century there was an exclusively male inheritance and property right in Great Britain, which could only be suspended in exceptional cases by special treaty or will regulations. In the event of death, all property generally passed to the next male relative, usually the oldest son. If he was still a minor, the mother could get ownership right up to the age of majority. If a testator only had daughters, the inheritance did not go to the daughters, but to a nephew or even to a distant male heir. Often the deceased therefore left binding dispositions in the will, so that the acceptance of the inheritance was linked to annual pension payments to the daughters and the wife.

If, in exceptional cases, a woman owned property, it usually passed to the husband upon marriage.

Accordingly, it is shown in the novel how Heathcliff brings himself into the relatives and thus inheritance of the Lintons through marriage (first he himself with Isabella, then his son with Catherine).

Real templates

- The village of Gimmerton, in the vicinity of which the novel is set, is based on the small town of Stanbury near Haworth , West Yorkshire , here are the geographical models adopted by biographers for Thrushcross Grange (the Ponden Hall estate) and Wuthering Heights (Top Withens, the highest Hills in the area with a farmhouse that is now destroyed).

- The landscape points Peniston Hill and Peniston Crag from the novel actually exist and lie between Haworth and Stanbury.

- The rock formation with the fairy cave that Catherine wants to visit with Nelly is the hollowed out rocky promontory Ponden Kirk near Stanbury.

- An inspiration for the adult Heathcliff was Jack Sharp, whose story Emily learned while she was employed as a teacher at Law Hill. Sharp was the adoptive son of a wealthy woolmaker family who intrigued to seize the family inheritance, and the builder of Law Hill, which, like Wuthering Heights, stands on a hill.

reception

Wuthering Heights ( Sturmhöhe ) was controversial in the 19th century, but the exaggeration of the negative reviews and the concealment of the positive parts of the contemporary reviews by the editor Charlotte Brontë was one of the reasons why the criticism was particularly emphasized in the literary history presentation. Criticisms in the contemporary reviews were that you could not really identify with any of the characters, since none of the characters in any way wholeheartedly sympathetic, they repelled rather than attracted. In addition, one cannot really empathize with any character, one feels pity every now and then, but that is again nullified by the offenses to be condemned. The nested plot is sometimes criticized as confusing, sometimes praised as an artistic balance, the language criticized as stilted and melodramatic or praised as polyphonic and authentic.

The drastic, unadorned depiction of evil in human nature and the extremely cleverly designed plot structure, down to the smallest detail, are praised. Critical reviews see Wuthering Heights as a work in the spirit of Shakespeare : an overrealistically heightened and intensified plot with mystical elements and with humanly realistic characters that go to extremes in their actions.

The individual reviews and analyzes fall into extreme positions to this day: Wuthering Heights is considered by some to be a masterpiece and cultural asset of the Victorian era , to others as an overrated curiosity of fiction.

Translations into German (selection)

The novel Wuthering Heights has been translated into German several times under different titles. A selection of translations:

- 1851: Wutheringshöhe , 3 volumes (volume 1, volume 2, volume 3), unknown translator

- 1908: The Sturmheidhof, also Sturmhöhe , Gisela Etzel

- 1938: The Sturmhöhe , Grete Rambach

- 1941: Weathered heights, Alfred Wolfenstein

- 1947: Stormy hills, also Sturmhöhe , Gladys von Sondheimer

- 1949: Sturmhöhe, Siegfried Lang

- 1951: Catherine Linton: Love and Hatred of Wuthering Heights , Martha Fabian

- 1986: Sturmhöhe , Ingrid Rein

- 1997: Sturmhöhe , Michaela Meßner

- 2016: Sturmhöhe , Wolfgang Schlüter

Translations without a year:

- undated: Sturmhöhe , Johannes F. Boeckel

- Untitled : Heights covered in storms , Karl Gassen

- o. J .: Stormy Heights , JB ship

Illustrations

The novel has been illustrated several times by various artists:

- 1924 - The British painter Percy Tarrant (1881–1930) produced 16 color illustrations for the publisher George G. Harrap.

- 1931 - The artist Clare Leighton (1899–1989) creates a series of woodcuts for the novel.

- In 1935 the illustrations by the painter Balthus , which were created between 1932 and 1935, are published.

- 1943 - Woodcuts by the German-American artist Fritz Eichenberg (1901–1990) for the US publisher Random House .

Adaptations

music

- Bernard Herrmann composed the opera Wuthering Heights between 1943 and 1951 ; Carlisle Floyd wrote an opera of the same name in 1958. Also Frédéric Chaslin set to music (with a libretto by PH Fisher) the novel as opera.

- The 1977 album Wind and Wuthering by the band Genesis , then dedicated to progressive rock , was inspired by the novel in terms of music and cover design. The album cover shows an autumn tree surrounded by clouds of fog. A two-part instrumental track on the album is named after the last words of the original English text: “Unquiet Slumbers for the Sleepers… In That Quiet Earth”.

- The British musician Kate Bush set the story of Cathy and Heathcliff to music on her debut album The Kick Inside in 1978 and landed a worldwide hit with Wuthering Heights , of which there are numerous cover versions today (including the New Zealand singer Hayley Westenra ).

- In 1979, John Ferrara and his band Ferrara made the novel the subject of his disco album Wuthering Heights.

- The title track of the Zodiac Mindwarp album One More Knife (1994) also refers to the novel; Heathcliff is mentioned by name. In the booklet of the CD there is a dedication to Emily Brontë.

- The composer Jim Steinman , according to his own account, was inspired by the book for his hit Its All Coming Back to Me Now . The song was interpreted by Celine Dion and Meat Loaf , among others .

- Cliff Richard released an album in 1995 called Songs from Heathcliff . The songs formed the basis for his musical Heathcliff (premiered in 1996 at Hammersmith Apollo ), which is based on the first half of the novel.

radio play

The radio play Sturmhöhe (two-part), edited by Kai Grehn, was produced in 2012 as a co-production by SWR2 and NDR Kultur . Speakers are u. a. Sebastian Blomberg , Jule Böwe , Franziska Wulf , Alexander Fehling and Bibiana Beglau .

- Storm height . Radio play by Kai Grehn, translation by Gisela Etzel, the Hörverlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-86717-931-7

Film adaptations

- 1920: Wuthering Heights (UK; silent film; with Milton Rosmer , Ann Trevor and Colette Brettel )

- 1939: Sturmhöhe ( Wuthering Heights ; USA; directed by William Wyler ; with Merle Oberon , Laurence Olivier , David Niven )

- 1948: Wuthering Heights (UK; made TV; with Kieron Moore , Patrick Macnee )

- 1950: Wuthering Heights (USA; made TV; with Charlton Heston , Una O'Connor )

- 1953: Wuthering Heights (UK; made for TV; directed by Rudolf Katscher ; with Richard Todd , Yvonne Mitchell )

- 1954: Abysses of Passion ( Abismos de pasión ; Mexico; Director: Luis Buñuel ; with Lilia Prado , Jorge Mistral )

- 1962: Wuthering Heights (UK; BBC television film; director: Rudolf Katscher; with Claire Bloom , Ronald Howard )

- 1967: Wuthering Heights (UK; BBC four-part series; with Ian McShane , Angela Scoular )

- 1970: Sturmhöhe ( Wuthering Heights ; UK; directed by Robert Fuest ; with Timothy Dalton , Ian Ogilvy )

- 1978: Wuthering Heights (UK; BBC five-part series; with Ken Hutchison )

- 1985: Sturmhöhe ( Hurlevent ; France, director: Jacques Rivette ; with Lucas Belvaux )

- 1988: Arashi ga oka (Japan; director: Yoshishige Yoshida ; with Yūsaku Matsuda )

- 1992: Stormy Passion ( Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights ; UK; directed by Peter Kosminsky; with Juliette Binoche , Ralph Fiennes , Janet McTeer )

- 1998: Wuthering Heights (UK; ITV ; with Orla Brady , Matthew Macfadyen )

- 2003: Wuthering Heights (USA; MTV television film; with Mike Vogel , Erika Christensen )

- 2004: Cime tempestose (Italy; TV film; with Alessio Boni )

- 2009: Emily Brontë's Sturmhöhe ( Wuthering Heights ; UK; ITV two-part; with Tom Hardy , Charlotte Riley )

- 2011: Wuthering Heights (UK; Director: Andrea Arnold ; with Kaya Scodelario )

- 2015: Dangerous Passion ( Wuthering High ; USA; TV film; with Paloma Kwiatkowski , Andrew Jacobs )

Note: Most of the film adaptations are limited to the first half of the novel until Cathy Earnshaw's death. The film adaptations of 1920, 1967, 1978, 1992, 1998 and 2009 cover the entire novel plot, with the BBC miniseries from 1967 and 1978 being designed to be particularly true to the original. The film adaptations from 2003 and 2015 transport the plot of the novel into the modern America of the 21st century.

Literary adaptations

- 1978 - Return to Wuthering Heights , continuation of Sturmhöhe , published under the names of Nicola Thorne and Anna L'Estrange.

- 1993 - Heathcliff , Jeffrey Caine novel telling Heathcliff's story in the years outside Gimmerton, ISBN 978-0-00-647604-7

- 1993 - H. — The Story of Heathcliff's Journey Back to Wuthering Heights , novel by Lin Haire-Sargeant, linking characters from Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre with Sturmhöhe , ISBN 978-1-879196-07-0 , German: Return to Sturmhöhe , Droemer Knaur, 1996, ISBN 978-3-426-65006-6

- 1997 - La migration de cœurs , novel by Maryse Condé, Robert Laffont publishing house, Paris, 1993, the Négritude trivial author relocates the plot to Guadeloupe and Cuba; German: Sturminsel , translation: Klaus Laabs, Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg, 1997, ISBN 3-455-00912-3

- 2004 - The Well of Lost Plots (dt .: The Fountain of manuscripts ) - in the novel by Jasper Fforde the characters from organizing Wuthering Heights a group therapy session.

- 2005 - Heathcliff's Tale , novel by Emma Tennant, a satire on the literary interpretations of Sturmhöhe , ISBN 978-1-872621-91-3

Audio books

- Sturmhöhe (read by Eva Mattes and Wolfram Koch , translation by Michaela Meßner), Patmos 2005, ISBN 978-3-491-91172-7

- Sturmhöhe (read by Gudrun Landgrebe ), Sounds of Seduction Audioproduktionen Köln 2010, ISBN 978-3-937071-14-5

- Sturmhöhe - Wuthering Heights (read by Beate Rysopp and Wolfgang Berger), AUDIOBUCH Verlag 2017, ISBN 978-3-95862-011-7

- Sturmhöhe (read by Rolf Boysen , translation by Grete Rambach), Hörverlag 2018, ISBN 978-3-8445-2210-5

- Sturmhöhe (read by Gert Westphal , translation by Grete Rambach), Der Audio Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3-7424-0679-8

Trivia

- The actor Heathcliff "Heath" Ledger (1979-2008) and his sister Katherine were named by their parents after the main characters from Storm Heights .

- Monty Python's Flying Circus showed in 1970 (season 2, episode 2) the sketch The Semaphore Version of Wuthering Heights ( "The winking alphabet version of Sturmhöhe" ).

literature

- Oskar Loerke: Ellis Bell [1910]. In: Reinhard Tgahrt (Ed.): Literary essays from the Neue Rundschau 1909–1941 , Lambert Schneider Verlag, Heidelberg / Darmstadt 1967, pp. 327–332. literature-online.tripod.com ( Memento from April 12, 2017 in the Internet Archive ; PDF)

- Harro H. Kühnelt: Emily Brontë - Wuthering Heights . In: Franz Karl Stanzel (ed.): The English novel - From the Middle Ages to the Modern . Volume II. Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1969, pp. 39-70.

- F. H. Langman: Emily Brontës "Wuthering Heights" . In: Willi Erzgräber (ed.): English literature from William Blake to Thomas Hardy (interpretations 8). Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. et al. 1970, pp. 186-204.

- 2016: Robert Sasse and Yannick Esters : Sturmhöhe: A book summary ( audio book , Audible , read by Yannick Esters)

Web links

- Filming in the IMDb

- Historical and biographical background to the novel (English)

- Radio play production Sturmhöhe

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eagleton, Terry. Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontës . London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- ↑ Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Imagination . New Haven: Yale UP, 2000.

- ↑ James Harley: The Villain in Wuthering Heights Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. (PDF) In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction . 13, No. 3, 1958, pp. 199-215. JSTOR 3044379 . Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ On the different interpretations of the main character, see the information from Harro H. Kühnelt: Emily Brontë - Wuthering Heights . In: Franz Karl Stanzel (ed.): The English novel - From the Middle Ages to the Modern , Volume II, Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1969, p. 68ff. See also Wuthering Heights as a Socio-Economic Novel . At: academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu . Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ↑ Inspirations for Wuthering Heights ( Memento from March 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Real Roman Backgrounds (Eng.)

- ↑ wuthering-heights.co.uk

- ↑ RS Sharma: Wuthering Heights: A Commentary Atlantic Publishers & Distributors 1999 ISBN 81-7156-491-7 , pp.

- ↑ Publication of Wuthering Heights and its Contemporary Critical Reception academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu

- ↑ The Novel as Dramatic Poem (II) 'Wuthering Heights' by DG Klingopulos. In Scrutiny, September 1947, pp. 269-286

- ↑ See the summary in Later Critical Response to Wuthering Heights . At: academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu . Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Volume 1 at books.google.de

- ↑ Volume 3 at books.google.de

- ↑ The Sturmheidhof at projekt-gutenberg.org

- ↑ shrouded heights at projekt-gutenberg.org

- ↑ Movement and Timelessness Emily Bronte: Storm Heights. Two-part arrangement by Kai Grehn. In: NDR / SWR, Wed., 19./26. December, 20.05–9.30 p.m.