North Wind Company

| date | December 31, 1944 to January 25, 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | Alsace , Lorraine |

| output | tactical Allied retreat |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers , Lieutenant General Alexander Patch , General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny |

Colonel General Johannes Blaskowitz , 1st Army : General of the infantry Hans von Obstfelder , General of the Infantry Siegfried Rasp |

| Troop strength | |

| ? | ? |

| losses | |

|

|

23,000 (fallen, wounded, other sorts) |

Prelude

Kesternich - Wahlerscheid

German attack

Losheimergraben - Clervaux - Stößer - Greif

Allied defense and counter-attack

Elsenborn ridge - St. Vith - Bastogne - Bure

German counterattack

base plate - north wind

1944: Overlord · Dragoon · Mons · Market Garden · Scheldt estuary · Aachen · Hürtgenwald · Queen · Alsace-Lorraine · Ardennes

1945: Nordwind · Bodenplatte · Blackcock · Colmar · Veritable · Grenade · Blockbuster · Lumberjack · Undertone · Plunder · Würzburg · Ruhrkessel · Nuremberg

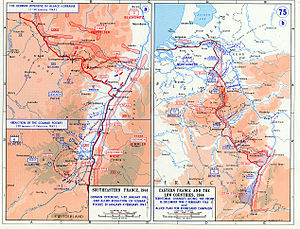

The company Nordwind was the last offensive of German armed forces on the Western Front during World War II , during which fighting took place in Alsace and Lorraine from December 31, 1944 to January 25, 1945 . Although the company led to political tensions between the US and France , known as the Strasbourg controversy , it is one of the lesser-known and sometimes misrepresented major operations of World War II ; In the public perception the simultaneous battles in the Ardennes and on the Vistula and Oder dominate .

Temporary planned as an alternative to the Ardennes offensive or to support it, the company was started when the attacks there had long since stopped. While German troops had already largely evacuated the Ardennes and the Soviet troops were about to capture Warsaw and shortly before their first successes in East Prussia , the fighting in Alsace reached its climax with the deployment of further German divisions. A substantial part of the fighting took place from January 8 to 20, 1945 in the area between Hagenau and Weißenburg , although fighting on the Vosges ridge and around a newly formed bridgehead on the Upper Rhine determined the events much more strongly. The battle ended after the withdrawal of American troops on the Moder line near Haguenau and their defensive success against the last German attacks on January 25th.

In contrast to the Ardennes offensive, which was mainly hampered by a lack of fuel, insufficient artillery support, insufficient reconnaissance and, above all, a lack of personnel and stubborn Allied resistance are the decisive reasons for the failure of Nordwind . The units deployed in this section of the front, weakened by the previous fighting in retreat, were not adequately replenished - a deficiency that was only compensated for with a delay by the deployment of reserves. The operational management was made more difficult by the fact that the operations room was not only in the area of Army Group G , but was divided between it and the newly formed Army Group Upper Rhine under the command of Heinrich Himmler ( Reichsführer SS ).

Starting position

On November 12, 1944, the 6th US Army Group , consisting of the 7th US Army and the French 1st Army , started the offensive on both sides of the Vosges in cooperation with the 3rd US Army . The allied armies broke through the Zaberner Steige and the Burgundian gate and reached the Upper Rhine on November 19th near Mulhouse and on November 23rd near Strasbourg . On the express orders of Dwight D. Eisenhower , the Allied units did not cross the Rhine but turned north. In early to mid-December they had largely pushed the German 1st Army back north from the Lower Alsace and included parts of the 19th Army in the Alsace bridgehead . The latter was taken out of Army Group G on December 2, 1944 and transferred to the newly formed Upper Rhine Army Group, whose command Heinrich Himmler received on December 10 and which was directly subordinate to the Fuehrer's headquarters . At the end of December 1944, after initial successes, the German Ardennes offensive came to a standstill (see Siege of Bastogne ) . In order to free up forces for an American counterattack in the Ardennes, the 7th US Army took over large parts of the front section of the 3rd US Army in Lower Alsace and Lorraine, which thus became the weakest section of the American front. On the other hand, the Commander-in-Chief West had several divisions that could be deployed from mid-January 1945 as reserves.

German planning

After the Ardennes offensive had made it necessary to move larger units of the 3rd US Army to the north, the staff of the Commander-in-Chief under General Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt decided to take advantage of the weakening of the enemy in Alsace. Confident by the evacuation of the American bridgeheads on the Saar, Rundstedt ordered the high command of Army Group G on December 21, 1944 to initiate local advances and to make arrangements for an attack to recapture the Zaberner Steige .

Three options have been developed for this attack, with the advantages and disadvantages listed:

| west of the Vosges | along the Vosges ridge | east of the Vosges |

|---|---|---|

|

+ well-developed road and path network + Protection of the right flank by the Saar - high probability of Allied air raids because of the open terrain - considerable reclassification of forces required |

+ Protection through hilly and wooded terrain + Fortifications of the Maginot line still in German hands - poorly developed road and path network - anti-tank terrain |

+ well-developed road and path network - Fortifications of the Maginot Line in American hands - good defense possibilities in the holy forest - Minefields |

After the approval of the advance along the Vosges ridge by von Rundstedt and Colonel General Johannes Blaskowitz (Commander in Chief of Army Group G ), Hitler ordered the western advance to be carried out in support of the main thrust with at least two tank and three infantry divisions. Given the weather conditions in the Vosges (it was a very cold winter), he had doubts about the stamina of the troops. Rundstedt changed his orders in this regard on December 22nd.

In fact, only this detailed planning had to be carried out, because as early as October 1944 the Wehrmacht command staff had developed studies for a counter-offensive in Alsace. Such an offensive was considered on November 17th and 25th as an attack on the flank of the Allied forces possibly pushing over the Rhine and was ultimately rejected in favor of the attack in the Ardennes. Now these studies could be used. In a meeting with Blaskowitz on December 24th, the goals of the operation were set. With the Zaberner Steige between Pfalzburg and Zabern , the lines of communication between the Allied forces in northern Alsace were to be cut off and the latter broken up. Subsequently, the connection to the 19th Army was to be established by an advance south . For this purpose, two shock groups were formed in the area of the 1st Army under General of the Infantry Hans von Obstfelder . The first - consisting of the XIII. SS Army Corps (two Volksgrenadier and one SS Panzergrenadier Division) - should break through the Allied lines at Rohrbach east of the Blies and then line up with the second group in the direction of Pfalzburg . The second group - consisting of the LXXXX. Army Corps (two Volksgrenadier divisions) and LXXXIX. Army corps (three infantry or people's grenadier divisions) - should attack from the area east of Bitsch in several wedges and then cooperate with the first group. Depending on the development of the situation, the offensive should then take place either east or west of the Vosges in the direction of the Pfalzburg – Zabern line.

In order to take advantage of a breakthrough, the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division and the 21st Panzer Division were kept in the Army Reserve. In the official language of December 25, 1944, the operation was given the code name "Operation North Wind".

On December 23, 1944, the southern Upper Rhine Army Group , which was under the command of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler , was included in the planning . She was asked to tie up the opposing forces there by undertaking raids and building bridgeheads across the Rhine north and south of Strasbourg . At times it was also considered to advance with parts of the 19th Army on Molsheim west of Strasbourg, which would also have cut the second, smaller line of the Allies in Lower Alsace. After Hitler had set the start of the offensive on December 31, 1944 at 11 p.m., the Army Group received its final orders. It was not to attack until the 1st Army units had taken possession of the eastern exits of the Vosges between Ingweiler and Zabern. Your divisions had the task of breaking through the opposing front north of Strasbourg and uniting with the 1st Army in the Hagenau - Brumath area . The execution of these initially secondary operations was the responsibility of the 19th Army under General of the Infantry Siegfried Rasp . In addition to smaller battalion-strength advances from the Alsace bridgehead , it planned the attack of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division at Gambsheim across the Rhine.

After the Allied forces had been smashed in Lower Alsace, a follow-up operation was planned for the Dentist company , an advance into the flank of the 3rd US Army .

Hitler's intention

Hitler associated the "Operation North Wind" not only with the prospect of a further partial success on the western front, but also with the idea of getting the deadlocked Ardennes offensive rolling again in this way. He presented these views on December 28, 1944 in a speech to the commanders and commanders involved:

“I totally agree with the measures that have been taken. I hope that we will succeed in moving the right wing in particular quickly forward [in the Bitsch area] in order to open the entrances to Zabern, then immediately push into the Rhine plain and liquidate the American divisions. The goal must be to destroy these American divisions. [...] The mere idea that things are offensive again at all has had a positive effect on the German people. And if this offensive is continued, if the first really great successes show up [...] you can be convinced that the German people will make all the sacrifices that are humanly possible. [...] So afterwards I would just like to appeal to you that you stand behind this operation with all your fire, with all your energy and with all your energy. That is a crucial operation. Your success will automatically bring about the success of the second [in the Ardennes]. [...] We'll master fate after all. "

German forces

In addition to the Volkssturm units and local police forces deployed in the bunkers of the West Wall on the Upper Rhine , there were numerous divisions on the German side, some of which were only regimental and some were inexperienced.

1st Army

Division into two storm groups, XIII. SS Army Corps as Sturmgruppe 1 for the attack west of the Vosges, LXXXX. Army Corps and LXXXIX. Army corps as Sturmgruppe 2 for the attack on the Vosges ridge.

| XIII. SS Army Corps | LXXXX. Army Corps | LXXXIX. Army Corps | other units of the 1st Army |

|---|---|---|---|

|

19th Army

| LXIV. Army Corps | LXIII. Army Corps | XIV. SS Army Corps | Army reserve |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Allied plans

While the 3rd US Army was still reorganizing to repel the German Ardennes offensive, the SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force) became aware of the challenges that the 6th US Army Group was facing with its now overstretched section of the front. In a follow-up discussion on December 26, 1944, Dwight D. Eisenhower , who had recently been promoted to General of the Army , informed the commander of the 6th US Army Group, Jacob L. Devers , that he was withdrawing the 6th US Army Group in order to shorten the front from the Upper Rhine to the Vosges ridge. Since neither this statement nor the subsequent urging of the SHAEF had the character of a formal order and Devers had doubts about the SHAEF's assessment of the situation after the Ardennes fiasco of the Allied military intelligence, he did not see a withdrawal as urgent. He just let it plan instead of carrying it out. According to his assessment, which was also shared by the commander of the 7th US Army Alexander Patch , a German attack on the Saar was most likely, especially since the Panzer Lehr Division , which has meanwhile been deployed in the Ardennes, carried out a disruptive attack here in December 1944 . Another possibility, but less likely because of the terrain, was an attack along the Vosges ridge, while a German attack in the Upper Rhine Plain was seen as absurd because of the sections of the Maginot Line held by the Americans.

For the reasons mentioned, Patch planned four fall arrest positions that could be used one after the other:

- Positional system of the Maginot Line

- Bitsch – Niederbronn –Moder

- Bitsch - Ingweiler - Strasbourg

- Eastern foothills of the Vosges.

Allied forces

On paper, the Allies had fewer divisions than the Germans, but they had a better manpower and material situation. The level of experience and training differed considerably from division to division; some associations had fought since the Italian campaign , while others had just been reorganized and only introduced in November 1944. The latter was particularly true of the French associations, many of which were recruited from the Resistance . Individual American divisions were just in the formation phase; the infantry regiments had already arrived, while the artillery components and logistics were still to be supplied.

7th US Army

| XV. US Corps | VI. US Corps | XXI. US Corps (SHAEF Reserve) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

1st French Army

| I. French Corps | II. French Corps |

|---|---|

|

|

course

Attack on the Vosges ridge, January 1st to 6th

The offensive, which the Allies only rudimentarily cleared up due to bad weather , began without artillery preparation - as a surprise attack - in the last evening hours of December 31, 1944.

The attack by Sturmgruppe 1 hit the deep defenses of the 44th and 100th US infantry divisions and, with the exception of a three-kilometer-deep break-in, remained in the Bliesbrücken - Rimlingen area. After German peaks of attack had taken Großrederchingen on January 3rd and had temporarily broken through to the town of Achen , this attack finally came to a standstill on January 5th.

The attack by Sturmgruppe 2 was much more successful. The mountainous and wooded area in the Vosges was only held by the 'Task Force Hudelson', which had little to counter the attacking German forces. On the German side, however, the lack of clearing up had a negative effect, which left the attacking units disoriented. The 361st Volksgrenadier Division , which a few weeks ago had been involved in retreat fighting there, gained the most space thanks to its knowledge of the area. Within the next four days, Storm Group 2 advanced 16 kilometers.

The development of the situation prompted Blaskowitz and Obstfelder to use the initial successes of Sturmgruppe 2 and to deploy the 6th SS Mountain Division "North", which had just been brought in from Norway . This association, which clearly had the highest operational value of all German divisions in this section of the front, competed over the 257th and 361st Volksgrenadier divisions on Wingen and Wimmenau . In the morning hours of January 4th, two battalions of this division occupied Wingen and overran an American battalion command post. However, since they had lost the communication links with their radio truck, they could not request reinforcements. American counterattacks initially failed because they were initially aimed at throwing just one company out of Wingen. However, since there was no support attack by the 19th Army / Army Group Upper Rhine, the Americans were able to withdraw forces from sections of the front on the Upper Rhine and start further counterattacks on Wingen. When American pressure became overpowering, the meanwhile exhausted German battalions withdrew from Wingen on the night of January 6th to 7th.

Strasbourg controversy

The unclear situation regarding the retreat behind the Vosges suggested by Eisenhower began to draw political circles during the attack on Zabern. On the afternoon of January 1st, the chief of staff at SHAEF called General Devers and accused the 7th US Army of disobeying orders for not evading the Vosges. Devers then stated that the relevant preparations had started, but would take time due to the local conditions. On the same day Devers Patch announced that his army would have to move behind the Vosges by January 5th and give up the Upper Rhine Plain including Strasbourg. Patch immediately began implementation by withdrawing the units deployed in the course of the Lauter to the south. At the same time as the order was given to Patch, Devers passed this information on to the French government via the French liaison officers. De Gaulle then protested in a letter to Devers. The background to the French stance was primarily the recent history of Alsace as a bone of contention between Germany and France. Strasbourg in particular, where Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle composed the Marseillaise in 1792 , enjoyed a status among the French that was only surpassed by the capital Paris. In addition, it was feared that a renewed German occupation would result in reprisals against those parts of the population who had openly shown their loyalty to France after the capture by the Allies on November 23, 1944 . Devers, who shared France's stance, sent his Chief of Staff, Major General Barr, to Eisenhower in Paris on January 2 to receive clear instructions. De Gaulle also contacted Roosevelt and Churchill and ordered Eisenhower to speak to Paris on January 3, where Churchill acted as mediator. De Gaulle described Eisenhower's decision as a national catastrophe, whereas Eisenhower initially stuck to his decision and blamed the French 1st Army for failing to break up the Alsace bridgehead . De Gaulle then threatened to end the French participation in SHAEF, while General Alphonse Juin , who was also present , made hints that France would deny the Allies the use of its rail network. Eisenhower finally accepted the French concerns with Churchill's praise. Major General Barr, who was also present, immediately passed the information on to Devers, even before the decision was fixed in writing on January 7th in the form of a communique. Devers stopped the withdrawal movements from the Lauter .

Fight in the Upper Rhine Plain

After Wingens had been cleared, the OKW abandoned the attack in the course of the Vosges or west of it and shifted its focus. The original intention of Army Group G to now lead the attack with armored forces on the eastern edge of the Vosges via the intermediate target Rothbach west of Hagenau was abandoned because of the situation development in the front section of the 19th Army described below, in favor of an attack directly in the Upper Rhine Plain eastwards from Haguenau.

New bridgehead near Gambsheim, January 5th to 10th

During the attack by Sturmgruppe 2 on Wingen, the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, which was subordinate to the 19th Army and had the lowest operational value of all the German divisions involved, succeeded in forming a bridgehead at the confluence on the night of January 4th and 5th of anger and moderation at Gambsheim . Since the American units - here Task Force Linden - could only defend this section of the front with reconnaissance troops and since the population in this region was pro-German, the soldiers of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division were able to cross the Rhine unhindered in their assault boats , following the bridgehead extend its security to Herlisheim and Offendorf and advance in the southwest to the outskirts of Kilstedt . The supply of the bridgehead was ensured by ferry service at night, as a bridge would have been exposed to air raids by the Allied air force. The Allies rated the threat from this bridgehead as so minor that they made no attempt to lock it down for the next three days, even though Patch told the commander of the VI. US Corps had given the order to break up the bridgehead on January 6th. It was not until January 8 that he put parts of the 12th US Armored Division on the bridgehead, namely Combat Command B (a maneuver element in brigade strength) against supposedly only 500 to 800 unorganized German infantrymen on the bridgehead. In fact, at this point in time, 3330 German soldiers - reinforced by anti-tank guns - were in well-developed positions. In contrast, the weak infantry component of the 12th US Armored Division reduced the operational value of this unit. Combat Command B competed at Herlisheim on January 8th. It is true that it was possible to penetrate Herlisheim with infantry; However, since the American tanks could be kept in check by the German anti-tank guns and the radio connection to the infantrymen was broken, the latter evacuated Herlisheim in the morning hours of January 10th.

Company solstice, January 8-12

The actual support of the 19th Army, code name company Sonnenwende , consisted in an attack from January 8, 1945 by the 198th Infantry Division deployed between the Rhine and Ill , parts of the 269th Infantry Division and the 106 Panzer Brigade from the Alsace bridgehead Strasbourg. The relevant section of the front had recently been handed over to the French 1st Army by the Americans . The German units succeeded in throwing back all the French forces deployed south-east of the Ill and thus regaining control of the triangle between Ill and Rhine. Three French combat groups were cut off in battalion strength and destroyed by January 13th. Nonetheless, the French forces succeeded in intercepting the German attack on January 12 on the Ill in the course of the villages of Benfeld , Erstein and Kraft and bringing it to a halt. The real goal - the capture of Strasbourg - was not achieved.

Fights for Hatten-Rittershofen, January 8th to 20th

The American armed forces deployed in the northeast corner of Alsace had already evacuated the area on the Lauter in the first days of January in implementation of Eisenhower's withdrawal order, thus giving up Reipertsweiler and Weißenburg. After de Gaulle's intervention, they moved into the first of the planned containment positions on the Maginot Line. Only in the Hatten area did the 21st Panzer Division and 25th Panzer Grenadier Division, pushing out of the Bienwald and merged into Kampfgruppe Feuchtinger , succeed in pushing beyond the Maginot Line. At the urging of Himmler, the OKW's intention was to advance via Hatten to Hagenau and to meet in the Bischweiler area with the forces opposing from the Gambsheim bridgehead, according to the VI. To enclose US corps in the Sufflenheim area and then destroy it, or at least tie up the Allied forces here head-on, so that storm group 2 standing on the Vosges ridge and the forces in the Gambsheim bridgehead - reinforced by the reserves originally intended for company dentists - on Hagenau advance and thus the VI. US Corps.

As a result, parts of this place and the neighboring Rittershofen changed hands again and again in bitter fighting, whereby neither Americans nor Germans could gain the upper hand, although the latter received reinforcements from the 7th Parachute Division from January 11th to 15th. The civilian population also suffered high losses because the Americans did not evacuate them. Simultaneous attempts to carry out the original attack by Sturmgruppe 2 on Zabern failed, although the 6th SS Mountain Division "North" succeeded in enclosing and breaking up an American combat group on January 16. In the meantime, the 7th Paratrooper Division managed to fight its way to the Gambsheim bridgehead on the left bank of the Rhine and thus establish a land connection.

Stalemate near Herlisheim, January 16-21

Since the attempt by Combat Command B to push in the Gambsheim bridgehead had failed on January 10, the commander of VI. US Corps entered the entire 12th US Division there on January 13, which started again on January 16, Combat Command B again on Herlisheim and Combat Command A on Offendorf and the nearby Steinwald. This time too, Combat Command B managed to penetrate Herlisheim, but the gains in terrain were lost again due to a German counterattack. Unnoticed by the Americans, the 10th SS Panzer Division put ferries across the Upper Rhine on the night of January 15-16 and moved into an area of disposal in the bridgehead. The divisional command post was relocated to Offendorf and began planning an escape from the bridgehead for January 17th. This attack started as planned before dawn and resulted in an undecided encounter with Combat Command A, who was also attacking (again). It became apparent that in the area criss-crossed by villages, the anger, and by embankments and drainage ditches, the value of tanks was low and they were easily prey to anti-tank guns and bazookas. An attempt by Combat Command B to bypass Herlisheim to the north also failed. On January 18, the 3rd / SS Panzer Division 10 belonging to the 10th SS Panzer Division succeeded in smashing a US tank battalion that had penetrated Herlisheim, capturing ten Sherman tanks and rubbing up a US infantry battalion that was also deployed there . On January 19, another battalion belonging to the 79th US Infantry Division was broken up near Drusenheim .

The 3rd French Infantry Division bloody repulsed attacks by the 10th SS Panzer Division on Kilstedt from January 17th to 21st .

US retreat behind the Moder, January 20th and 21st

Despite the defensive successes of the French at Kilstedt, there was a risk that the 10th SS Panzer Division would break out of the bridgehead further north, where it had just broken or worn out three American battalions. With an advance from the Drusenheim area to the west in the course of the northern banks of the Mold, they could have turned the American front off its hinges at Hatten and Rittershofen. The danger of another attack by Sturmgruppe 2 and the exhausting battle for Hatten and Rittershofen completed a picture of the situation, according to which the front arch of VI. US Corps was slowly becoming untenable. Although the removal of the German front in the Ardennes freed the 101st US Paratrooper Division and the 28th US Infantry Division and relocated them to Alsace, bad weather conditions delayed the arrival of these reinforcements. Patch succeeded in obtaining Dever's consent for a retreat, with which the corps on the south bank of Rotbach, Moder and Zorn could take up the second defensive position in the course of a significantly shortened front line.

The withdrawal movement began in the night of January 20th to 21st and was favored by bad weather; German troops only noticed the withdrawal after it had already taken place. They pushed in on January 22nd and extended the land connection to the Gambsheim bridgehead.

German forces push up until January 25th

The withdrawal of the Allied forces led to the abandonment of large sections of the Maginot Line . German forces were as close to their operational goal of Zabern as they were during the fighting for the intermediate goal of Wingen. Hence the German intention to advance on Zabern remained unchanged. Encouraged by the gains in terrain, German forces immediately made the unsuccessful attempt to take Hagenau and Bischweiler . On the night of January 24th to 25th, parts of three German divisions competed in the area between Neuburg and Schweighausen , but were beaten back after initial successes. Also on January 25, attacks by the 6th SS Mountain Division "North" on Bischholz and Schillersdorf were repulsed. At this point in time, given the collapse of the German front in the east, it was no longer possible to continue the attacks. Hitler therefore ordered the offensive to be stopped. As a result, on January 27, the 21st Panzer Division and the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division were pulled out and relocated to the Eastern Front, the 10th SS Panzer Division followed in February.

consequences

After the offensive was over, German forces again occupied around 40 percent of Alsace. As tactical successes, they were able to record a shortening of the front and fewer losses compared to the Allies. However , they were denied strategic successes; they succeeded in smashing notable Allied forces, as well as taking Strasbourg.

By dodging behind the Moder, the Allied forces even gained freedom of action for an attack on the Alsace bridgehead, which led to the breaking up of several German divisions in the Vosges Mountains and the removal of this bridgehead on February 9, 1945. During this period, parts of the former Gambsheim bridgehead were recaptured, while the area between Moder and the German starting positions was only cleared by German troops during Operation Undertone in March 1945.

From a strategic point of view, the company Nordwind - similar to the remaining German units in the Ardennes - tied forces which, given the collapse of the eastern front , would have been needed there much more urgently; Nordwind was only stopped at a time when the Red Army had already overrun half of East Prussia ( East Prussian Operation (1945) from January 13, 1945) and encircled Posen . This development of the situation could not be reversed by the relocation of the divisions previously deployed in Alsace.

All tactical successes could have been bought at a significantly lower price by clearing the Alsace bridgehead. The bitter fighting did nothing to change the outcome of the war. However, even after the failure of the Battle of the Bulge among the Western Allies, they maintained the impression that the Third Reich was not yet at the end of its tether.

The Strasbourg controversy was one of the reasons for de Gaulle's partial break with NATO in 1966 and even in the Federal Republic of Germany raised doubts about American support in the event of a Soviet attack.

literature

- Richard Engler: The Final Crisis: Combat in Northern Alsace, January 1945. Aberjona Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-9666389-1-2 .

- Robert Ross Smith, Jeffrey J. Clarke: Riviera To The Rhine. The official US Army History of the Seventh US Army. Diane Pub Co. 1993, ISBN 978-0-7567-6486-9 .

- Keith Bonn: When the Odds Were Even: The Vosges Mountains Campaign, October 1944 - January 1945. Presidio Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-345-47611-1 .

- Steven Zaloga : Operation North Wind 1945 - Hitler's last offensive in the West. Osprey Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84603-683-5 .

- Charles Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge: Operation Northwind. History Press Spellmount, 2001, ISBN 978-1-86227-399-3 .

- John Keegan : The Second World War. Rowohlt , Berlin 2004, ISBN 978-3-87134-511-1 .

- David Colley: Decision at Strasbourg: Ike's Strategic Mistake to Halt the Sixth Army Group at the Rhine in 1944. US Naval Inst Pr, 2008, ISBN 978-1-59114-133-4 .

- Percy E. Schramm (ed.): War diary of the high command of the Wehrmacht. Vol. 4, Bonn 2002, ISBN 3-88199-073-9 .

- Mercadet Léon: La Brigade Alsace-Lorraine. Grasset, Paris 1984, ISBN 978-2-246-30811-9 .

Web links

- Website of the large shelter museum in Hatten

- Battle History of the 44th ID (Nordwind & the US 44th Division)

- 14th Armored Division Combat History

- The Ardennes-Alsace campaign US Army brochure

- The NORDWIND Offensive (January 1945) on the website of the 100th Infantry Division contains a list of German primary sources regarding the operation.

- Smith, Clarke: Riviera To The Rhine. The official US Army History of the Seventh US Army.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d Smith, Clark: Riviera To The Rhine. P. 527.

- ↑ cf. War diary of the Wehrmacht High Command. Vol. 8, p. 1014.

- ↑ See only Ian Kershaw , according to which the offensive was already over on January 3, 1945 ("..., it made little headway and ground to a halt as early as January 3."): The End. London 2011, ISBN 978-0-14-101421-0 , p. 165.

- ↑ on this Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 25.

- ^ Bonn: When the odds were even. P. 103 ff.

- ^ David Colley: Decision at Strasbourg. P. 134 ff.

- ^ Bonn: When the odds were even. P. 147 ff.

- ^ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. p. 19.

- ↑ detailed war diary of the high command of the armed forces. P. 1349.

- ^ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. p. 26.

- ^ Bonn: When the odds were even. P. 199.

- ↑ a b War diary of the Wehrmacht High Command. P. 1347.

- ↑ War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. P. 443; Walter Warlimont: In the headquarters of the German Wehrmacht 1939 to 1945. Augsburg 1990, p. 522.

- ↑ War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. P. 1349.

- ↑ War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. Pp. 1347-1349.

- ↑ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 27.

- ↑ Quoted from: Walter Warlimont: In the headquarters of the German Wehrmacht 1939 to 1945. Augsburg 1990, pp. 522–524.

- ↑ So at least the expressly German designation in Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 26; see. but also Bonn: When the odds were even. Pp. 199, 200, who speaks of Main Attack and Supporting Attack.

- ↑ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 28.

- ↑ a b c Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 29.

- ^ Smith, Clark: Riviera To The Rhine. Pp. 495, 496.

- ^ Smith, Clark: Riviera To The Rhine. P. 496.

- ↑ In detail Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 37 ff.

- ↑ In detail Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 40 ff.

- ↑ In Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 40 ff. Not mentioned, cf. but Mercadet Léon: La Brigade Alsace-Lorraine. P. 285.

- ↑ a b Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 44.

- ↑ cf. War diary of the Wehrmacht High Command. Vol. 8, p. 989.

- ^ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 46.

- ^ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 47 f.

- ↑ a b Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 52.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 46, who incorrectly names Alphonse Daudet as the composer.

- ↑ a b c Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 53.

- ↑ a b c Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. pp. 59, 69.

- ↑ clear words in Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 57.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 81.

- ↑ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 65.

- ↑ a b c Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 69.

- ↑ cf. War diary of the Wehrmacht High Command. Vol. 8, pp. 1006-1014.

- ↑ cf. Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. p. 59.

- ↑ without explicitly naming the villages of Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. pp. 59, 69.

- ↑ War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. Vol. 8, p. 1351.

- ↑ in detail Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 59–65.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 128 f.

- ↑ War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. Vol. 8, p. 1019.

- ^ The Ardennes-Alsace campaign US Army brochure, p. 49

- ↑ War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. Vol. 8, pp. 1021, 1027.

- ^ A b Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 72.

- ^ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 72, Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 133, cf. but Smith, Clark: Riviera To The Rhine. P. 523, according to which only parts of the 10th SS Panzer Division were transported by ferries, and the bulk of this division in cooperation with two assault gun brigades, the 7th Paratrooper Division and another battalion from the Lauterburg area along the Rhine Fought free way to the beachhead. This representation is dubious insofar as the division would thereby be torn apart and thus not feasible. In addition, the division would have had an open right flank that the Americans could have pushed into. In addition, the attacking division would have had to cross two bodies of water, the Sauer and the Moder.

- ↑ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 72 f.

- ↑ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 73.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 138.

- ↑ a b Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 74.

- ↑ See Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 138; see. but also the somewhat unsatisfactory explanation in Zaloga, p. 74, according to which the withdrawal was only carried out despite the supply of forces no longer needed in the Ardennes because the exhausting struggle for the two villages was not to be continued.

- ↑ Cf. Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 74.

- ↑ See Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 139.

- ↑ See Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. Pp. 144-148.

- ↑ Cf. Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 78 f., Who writes here that the land connection has been established. However, this contradicts his map material, which shows that a narrow land connection already existed on January 6, or was established between this date and the US withdrawal.

- ↑ cf. War diary of the Wehrmacht High Command. Vol. 8, p. 1356.

- ^ A b Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945. P. 76.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. Pp. 152, 153.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 153 f.

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 155.

- ↑ Cf. Zaloga: Operation Nordwind 1945. P. 85.

- ^ Zaloga: Operation North Wind 1945 , which only indicates this in several places.

- ↑ Cf. Keegan: The Second World War. P. 653.

- ↑ on the development of the situation in East Prussia on January 25, cf. instead of many just Dieckert & General der Infanterie a. D. Horst Großmann: The struggle for East Prussia. Motorbuch, 10th edition 1994, ISBN 3-87943-436-0 (see attached map).

- ^ Whiting: The Other Battle of the Bulge. P. 48.