Global Hunger Index

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is an instrument with which the hunger situation is recorded and tracked on a global, regional and national level. The report, published annually in October, describes the spread of hunger in individual countries and measures both progress and failure in the global fight against hunger.

The index was originally developed by the International Research Institute for Food and Development Policy ( IFPRI ) in cooperation with Welthungerhilfe , a German aid organization, and was published for the first time in 2006. In 2007, the Irish non-governmental organization (NGO) Concern Worldwide joined as co-editor. In 2018, IFPRI handed the project over to its long-term partners Welthungerhilfe and Concern Worldwide, who have since continued the WHI as a joint project.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2019 - the fourteenth in a series of annual reports - depicts the hunger situation worldwide, by region and at national level using a multidimensional approach by assigning a corresponding numerical value. The GHI scores can be used to rank countries and compare current scores with past scores. The 2019 GHI shows that since 2000, global progress has been made in combating hunger and malnutrition; however, in some regions hunger and malnutrition persist and in some cases have worsened.

In addition to the assessments, the report addresses a key topic each year. The following topics have been focused in recent years:

- 2019: How climate change aggravates hunger

- 2018: Flight, displacement and hunger

- 2017: How inequality creates hunger

- 2016: The Commitment to End Hunger

- 2015: hunger and armed conflict

- 2014: The challenge of hidden hunger

- 2013: Strengthening resilience, securing nutrition

- 2012: Secure food when land, water and energy become scarce

- 2011: How rising and fluctuating food prices exacerbate hunger

- 2010: The chance of the first 1000 days

- 2009: How the financial crisis exacerbates hunger and why women matter

In addition to the annual GHI, the Hunger Index for India (ISHI) was published in 2008. A subnational hunger index was published for Ethiopia in 2009.

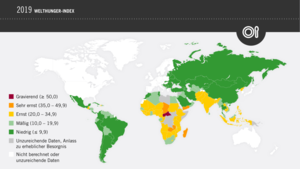

Calculation of the index

The GHI ranks countries on a 100-point scale, with 0 (no hunger) being the best and 100 being the worst, although none of these extreme values has ever been reached in practice. Values below 10.0 mean “low” hunger, values from 10.0 to 19.9 indicate “moderate” hunger, values from 20.0 to 34.9 indicate “serious” and from 35.0 to 49.9 “very” "serious" hunger, and values of 50.0 or above indicate a "serious" hunger situation.

The GHI combines four indicators:

- the percentage of undernourished in the population;

- the proportion of children under five years of age who are wasted;

- the proportion of children under the age of five who are stunted;

- the under-five mortality rate.

The data and projections on which the 2018 GHI is based refer to the years 2013 to 2017 - the period from which the most recent data available for all four components of the GHI come. The data on malnutrition come from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Child wasting and stunting data comes from UNICEF , the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank and the WHO's continuously updated global database on child growth and malnutrition; in addition, the latest findings from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) as well as statistics from UNICEF were incorporated. If original data were not available, the most recent data available was used to estimate the GHI indicators.

GHI 2019

The Welthungerhilfe presented on October 15, the Global Hunger Index for 2019 - the WHI has one for 47 countries serious or very serious situation out. For the Central African Republic , the assessment of a severe hunger situation even applies . The 2019 report focuses on the relationship between hunger and climate change.

Global and regional trends

The 2019 Global Hunger Index (GHI) shows that the global hunger situation falls on the threshold between the GHI categories serious and moderate - even though the GHI value has fallen from 29.0 in 2000 to the current 20.0. which corresponds to an improvement of 31 percent. Hunger levels in 47 countries around the world are still serious or very serious and in one country serious . The hunger situation varies greatly from region to region. The hunger situation in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa remains serious at 29.3 and 28.4 respectively . These values are significantly higher than the values in all other regions. South Asia's high GHI score of 29.3 is largely due to high child malnutrition rates: the proportions of emaciated or stunted children there are the highest in the report. Sub-Saharan Africa also has a serious hunger situation with a GHI score of 28.4 . This is largely due to the high rates of malnutrition and child mortality - the highest in the report. And the growth retardation rate in children is almost as high as in South Asia. While the proportion of undernourished people in the population fell continuously between 1999–2001 and 2013–2015, this trend has been worryingly reversed since then and the value is rising again. These values are in stark contrast to the values of East and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean as well as Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, which are between 6.6 and 13.3 and thus represent a low or moderate level of hunger . However, in these regions too, individual countries show serious or very serious hunger situations.

Precedence

| Rank 1 | country | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries with a GHI score below 5.0 jointly occupy ranks 1 to 17. 2 |

|

≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 |

|

|

9.8 | 7.2 | 5.1 | ≤5 | |

|

|

8.2 | 7.8 | 6.9 | ≤5 | |

|

|

≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

6.2 | 5.5 | 5.0 | ≤5 | |

|

|

6.1 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

5.3 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

5.6 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

6.0 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

- | - | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

8.3 | 6.4 | 5.6 | ≤5 | |

|

|

7.3 | 6.0 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

10.2 | 7.3 | 5.4 | ≤5 | |

|

|

13.7 | ≤5 | ≤5 | ≤5 | |

|

|

7.7 | 8.1 | 5.4 | ≤5 | |

| 18th |

|

12.0 | 7.0 | 5.4 | 5.3 |

| 19th |

|

6.6 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.4 |

| 20th |

|

11.0 | 12.4 | 8.6 | 5.5 |

| 21st |

|

7.7 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 5.6 |

| 22nd |

|

10.3 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 5.8 |

| 23 |

|

10.6 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 6.2 |

| 23 |

|

10.7 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 6.2 |

| 25th |

|

15.8 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 6.5 |

| 25th |

|

- | - | 6.7 | 6.5 |

| 27 |

|

11.3 | 10.8 | 9.9 | 6.7 |

| 28 |

|

21.5 | 16.6 | 15.1 | 7.0 |

| 29 |

|

27.5 | 17.3 | 12.1 | 7.4 |

| 30th |

|

18.3 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 7.8 |

| 31 |

|

13.5 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 7.9 |

| 32 |

|

8.6 | 8.6 | 9.7 | 8.2 |

| 33 |

|

14.0 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 8.3 |

| 34 |

|

11.5 | 13.7 | 9.2 | 8.5 |

| 35 |

|

19.3 | 14.0 | 12.4 | 8.8 |

| 35 |

|

20.9 | 18.2 | 12.5 | 8.8 |

| 37 |

|

9.9 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 8.9 |

| 38 |

|

12.1 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 9.1 |

| 39 |

|

18.3 | 17.2 | 12.8 | 9.2 |

| 39 |

|

14.5 | 10.4 | 8.4 | 9.2 |

| 39 |

|

20.2 | 18.3 | 12.6 | 9.2 |

| 42 |

|

15.8 | 17.7 | 10.0 | 9.4 |

| 43 |

|

16.3 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 9.6 |

| 43 |

|

15.3 | 14.0 | 12.2 | 9.6 |

| 45 |

|

31.8 | 25.0 | 15.8 | 9.7 |

| 45 |

|

18.3 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 9.7 |

| 47 |

|

15.6 | 12.9 | 10.6 | 10.3 |

| 48 |

|

12.1 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 10.5 |

| 49 |

|

23.6 | 17.8 | 14.7 | 10.7 |

| 50 |

|

16.0 | 12.5 | 11.0 | 10.8 |

| 51 |

|

18.6 | 17.0 | 13.2 | 11.3 |

| 52 |

|

13.7 | 15.6 | 9.8 | 11.4 |

| 53 |

|

9.1 | 10.3 | 8.0 | 11.6 |

| 54 |

|

21.8 | 17.1 | 15.0 | 11.8 |

| 55 |

|

18.0 | 16.8 | 16.0 | 12.6 |

| 56 |

|

20.9 | 17.8 | 14.8 | 12.9 |

| 57 |

|

15.5 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 13.1 |

| 58 |

|

24.6 | 17.6 | 16.2 | 13.3 |

| 59 |

|

28.7 | 22.0 | 18.3 | 14.0 |

| 59 |

|

19.2 | 22.7 | 16.6 | 14.0 |

| 61 |

|

16.3 | 14.3 | 16.3 | 14.6 |

| 62 |

|

28.2 | 23.8 | 18.8 | 15.3 |

| 63 |

|

30.3 | 27.1 | 21.6 | 15.4 |

| 64 |

|

20.8 | 18.9 | 16.4 | 15.8 |

| 65 |

|

15.2 | 12.7 | 8.4 | 16.9 |

| 66 |

|

22.4 | 21.2 | 18.0 | 17.1 |

| 67 |

|

36.3 | 27.5 | 23.6 | 17.9 |

| 68 |

|

26.4 | 24.8 | 23.8 | 18.7 |

| 69 |

|

44.4 | 36.4 | 25.9 | 19.8 |

| 70 |

|

25.8 | 26.8 | 24.9 | 20.1 |

| 70 |

|

25.8 | 21.4 | 20.5 | 20.1 |

| 72 |

|

27.7 | 24.1 | 22.0 | 20.6 |

| 73 |

|

36.8 | 31.3 | 24.5 | 20.8 |

| 74 |

|

29.6 | 27.9 | 26.5 | 20.9 |

| 75 |

|

27.5 | 26.3 | 22.5 | 21.8 |

| 76 |

|

39.7 | 33.7 | 26.2 | 22.6 |

| 77 |

|

43.6 | 29.4 | 27.6 | 22.8 |

| 78 |

|

44.5 | 37.7 | 31.1 | 23.0 |

| 79 |

|

33.1 | 30.4 | 26.2 | 23.2 |

| 80 |

|

33.4 | 31.5 | 28.1 | 23.6 |

| 81 |

|

39.3 | 37.0 | 27.2 | 23.9 |

| 82 |

|

36.7 | 33.3 | 28.3 | 24.0 |

| 83 |

|

44.2 | 38.4 | 27.4 | 24.1 |

| 84 |

|

33.8 | 35.3 | 30.9 | 24.9 |

| 84 |

|

30.7 | 28.4 | 30.6 | 24.9 |

| 86 |

|

36.9 | 32.7 | 27.6 | 25.2 |

| 87 |

|

47.7 | 35.9 | 30.5 | 25.7 |

| 88 |

|

36.1 | 30.7 | 30.3 | 25.8 |

| 88 |

|

46.3 | 48.1 | 36.8 | 25.8 |

| 90 |

|

33.4 | 30.6 | 24.9 | 26.7 |

| 91 |

|

43.6 | 36.8 | 30.7 | 27.4 |

| 92 |

|

40.3 | 32.9 | 30.9 | 27.7 |

| 93 |

|

40.8 | 34.2 | 29.9 | 27.9 |

| 94 |

|

38.3 | 37.0 | 35.9 | 28.5 |

| 95 |

|

42.2 | 35.9 | 34.1 | 28.6 |

| 96 |

|

49.9 | 42.3 | 35.3 | 28.8 |

| 97 |

|

55.9 | 46.0 | 37.4 | 28.9 |

| 98 |

|

56.6 | 44.0 | 32.4 | 29.1 |

| 99 |

|

42.1 | 40.3 | 31.0 | 29.6 |

| 100 |

|

65.1 | 50.3 | 38.6 | 29.8 |

| 101 |

|

52.1 | 42.4 | 36.6 | 30.2 |

| 102 |

|

38.8 | 38.9 | 32.0 | 30.3 |

| 103 |

|

53.6 | 51.1 | 40.8 | 30.4 |

| 104 |

|

38.9 | 33.0 | 30.8 | 30.6 |

| 105 |

|

46.9 | 43.9 | 36.6 | 30.9 |

| 106 |

|

37.3 | 37.1 | 32.0 | 31.0 |

| 107 |

|

- | - | - | 32.8 |

| 108 |

|

52.1 | 43.2 | 34.3 | 33.8 |

| 109 |

|

39.1 | 39.6 | 35.8 | 34.4 |

| 110 |

|

- | 41.8 | 42.3 | 34.5 |

| 111 |

|

42.7 | 45.1 | 48.8 | 34.7 |

| 112 |

|

48.6 | 42.4 | 36.0 | 34.9 |

| 113 |

|

52.3 | 46.0 | 42.8 | 38.1 |

| 114 |

|

43.2 | 43.4 | 36.2 | 41.5 |

| 115 |

|

51.5 | 52.1 | 50.9 | 44.2 |

| 116 |

|

43.2 | 41.7 | 34.5 | 45.9 |

| 117 |

|

50.7 | 49.5 | 42.0 | 53.6 |

Legend

| category | value |

|---|---|

| Countries with a serious GHI score | ≥ 50 |

| Countries with a very serious GHI score | 35.0-49.9 |

| Countries with a serious GHI score | 20.0-34.9 |

| Countries with a moderate GHI score | 10.0-19.9 |

| Countries with a low GHI score | ≤ 9.9 |

- = No data available. Some countries did not exist in their current borders in the given year or reference period.

The rankings and index values in this table cannot be compared directly to rankings and index values from previous reports. The colors correspond to the categories on the WHI severity scale.

1 Ranking according to GHI scores for 2019. Countries with identical GHI scores for 2019 receive the same ranking (for example, Mexico and Tunisia both rank 23). The following countries could not be included due to missing data: Bahrain , Bhutan , Burundi , Comoros , Democratic Republic of the Congo , Equatorial Guinea , Eritrea , Libya , Moldova , Papua New Guinea , Qatar , Somalia , South Sudan , Syria and Tajikistan .

2 The 17 countries with GHI scores below 5 for 2019 are not classified individually but together in ranks 1 to 17. The differences between their values are minimal.

Main topic in the GHI 2019: How climate change exacerbates hunger

The 2019 GHI makes it clear that climate change is making it increasingly difficult to feed the world population adequately and sustainably. Climate change has direct and indirect negative effects on food security and hunger through changes in production and availability, access, quality and use of food, as well as the stability of food systems. In addition, climate change can contribute to conflict, especially in vulnerable and food insecure regions. This creates a double vulnerability for communities that goes beyond their adaptive capacity. Climate change also presents us with the challenge of four central injustices that occur at the interface with food security:

- responsibility for the development of climate change,

- the effects of climate change on future generations,

- the consequences of climate change for vulnerable population groups in the Global South and

- the capacities to adapt to the effects of climate change.

Current measures are insufficient for the extent of the threat that climate change poses to food security. Transformation - a fundamental change in human and natural systems - is recognized today as crucial for the implementation of a climate-resistant development that can also achieve “no hunger”. Individual as well as collective values and behaviors must therefore change towards more sustainability and promote a more equitable distribution of political, cultural and institutional power in society.

GHI 2018

The Welthungerhilfe presented on October 11, the Global Hunger Index 2018 - the WHI has for 51 countries a "serious" or "very serious" situation out. For the Central African Republic , the assessment “severe hunger situation” even applies. The 2018 report focuses on the relationship between hunger, flight and displacement.

Global and regional trends

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2018 shows that the global hunger situation can still be classified in the serious category - even though the GHI value has fallen from 29.2 in 2000 to 20.9, which is an improvement of 28 percent. Hunger levels are still “serious” or “very serious” in 51 countries around the world and “serious” in one country.

The hunger situation varies greatly from region to region. The hunger situation in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa remains “serious” at 30.5 and 29.4 respectively. These values are in stark contrast to the values of East and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean as well as Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, which are between 7.3 and 13.2 and thus a "low" or " show moderate “hunger levels.

In South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the levels of malnutrition, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality are unacceptably high. Since 2000, the proportion of stunted growth children in South Asia has fallen from around half to a third, but the region still has the highest value in the world. The emaciation rate among children in South Asia has even increased slightly since 2000. On the other hand, the values for malnutrition and child mortality are higher in sub-Saharan Africa. Conflicts and unfavorable climatic conditions - individually or in combination - have exacerbated malnutrition there.

The high under-five mortality rate in sub-Saharan Africa is also partly due to conflict, with rates around twice as high in fragile states as in stable ones. The ten countries with the highest under-five mortality rates in the world are all in sub-Saharan Africa, and seven of them are classified as fragile states.

Main topic in the GHI 2018: displacement, displacement and hunger

This year's GHI essay examines displacement, displacement and hunger - intertwined problems affecting some of the world's poorest and most conflicted regions. There are an estimated 68.5 million displaced people worldwide, including 40 million internally displaced persons, 25.4 million refugees and 3.1 million asylum seekers. For these people, hunger can be both a cause and a consequence of flight and displacement. Aid to food insecure displaced persons needs to be improved in four key areas, as follows:

- Addressing hunger and displacement as political issues

- Apply more holistic approaches to long-term displacement

- Support for displaced people at risk of hunger in their regions of origin

- Recognize the resilience of displaced people

The 2018 Global Hunger Index contains recommendations for a more effective and holistic response to displacement and hunger: focus on particularly vulnerable regions and groups, implement long-term solutions and share responsibilities.

Individual evidence 2018

- ↑ 2018 Global Hunger Index: 124 million people suffer from acute hunger. In: tagesspiegel.de . Retrieved October 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Current results. Trends: global, regional, national. In: Global Hunger Index. Retrieved October 31, 2018 (expert report with current hunger figures).

- ^ Laura Hammond: Topics. Flight, displacement and hunger. In: Global Hunger Index. Retrieved October 31, 2018 .

GHI 2017

Global and regional trends

Despite the long-term progress in combating hunger demonstrated by the 2017 GHI, millions of people are still suffering from chronic hunger and in many places there are acute food crises or even famine. Compared to the GHI 2000, this year's total has fallen by 27 percent. In one of the 199 countries assessed in this year's report, the situation is classified as "serious" according to the GHI severity scale; seven countries correspond to the “very serious” category; 44 countries in the "serious" category and 24 countries in the "moderate" category. The values are “low” in only 43 countries.

South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are the most hungry regions. The values here correspond to the “serious” category (30.9 and 29.4). The values for East and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States represent “low” and “moderate” hunger situations (between 7.8 and 12.8). However, these mean values hide some worrying results within the individual regions, such as values in the “serious” category for Tajikistan, Guatemala, Haiti and Iraq and the “very serious” category for Yemen and “serious” hunger situations in half of all countries in East and Southeast Asia, the mean of which is improved by China's low of 7.5.

GHI scores for 2017 could not be calculated for 13 countries because no data on the prevalence of undernutrition were available for them and, in some cases, no data or estimates on stunted growth and wasting in children were available either. However, the countries for which no data are available may be those that suffer the most. Based on available data and information from international organizations working on hunger and malnutrition, it is clear that nine out of 13 countries with insufficient data are of major concern: Burundi, the Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Libya, Papua New Guinea , Somalia, South Sudan and Syria.

How inequality creates hunger

On the one hand, the GHI 2017 sheds light on the inequality in the progress made in the fight against hunger worldwide. Furthermore, the different dimensions of inequality are discussed, such as the unequal distribution of power, which can massively influence the nutritional situation of an individual. Achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goal of “Leaving No One Behind” requires approaches in the fight against hunger and malnutrition that, on the one hand, focus more on the unequal spread of hunger and, on the other, focus more on the power imbalance that the effects of poverty and marginalization in context exacerbated by malnutrition. The report emphasizes: the importance of a power analysis, which is necessary in order to identify all forms of power that determine the hunger situation; the importance of strategic actions targeting centers of power; the need to strengthen the hungry and malnourished in order to counteract the loss of their food sovereignty.

Regional and national trends

With 815 million people, the hunger figures are unbearably high. But compared to the GHI of 2000, this year's total has fallen by 27 percent, a positive trend. The values for 14 countries have improved by at least 50 percent compared to the reference year 2000. Only one country shows no progress: the Central African Republic. In 2017, she was also at the bottom of the country ranking and had a “serious” hunger situation. Seven other countries are in a "very serious" hunger situation: Chad, Liberia, Madagascar, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Sudan and Yemen. Most of these countries have suffered crises or violent conflicts. When publishing the latest hunger figures, the United Nations also pointed to a one percent increase in global malnutrition due to violent conflicts and disasters (from 2015 to 2016). Even if this negative change affects only one indicator of the GHI, this could slow the positive trend overall in the future. The 2017 GHI rates the hunger situation of only 43 countries as “low”. The goal of the 2030 Agenda, “Zero Hunger by 2030”, is at risk. Most people go hungry in countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. The classification of the hunger situation there is "serious". For East and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa as well as Latin America, Eastern Europe and the CIS countries, the rating is better. The countries are in the “low” or “moderate” categories.

Political recommendations for action

The 2017 Global Hunger Index provides the following political recommendations for action to fight hunger in a sustainable manner:

- Democratize national food systems

- Expand opportunities to participate in international discussions on nutrition policy

- Guarantee rights and space for civil society participation

- Protecting citizens and ensuring standards in business and trade

- Analyze power structures, shape policies better

- More support for smallholders

- Promote equality through education and social safety nets

- Use current data to hold governments accountable

- Invest in the global sustainability goals and disadvantaged people

GHI 2016

The 2016 Global Hunger Index was published in October 2016. Compared to this year's reference year 2000, the value has improved by 29 percent. Twenty-two countries have reduced their GHI scores by 50 percent or more compared to the year 2000. Despite this progress, 795 million people around the world are still starving, every fourth child is restricted in their physical and mental development, and 3.1 million children are still dying of malnutrition. The hunger values in 50 of 118 countries are still rated as "serious" or "very serious" with GHI scores.

Regional and national trends

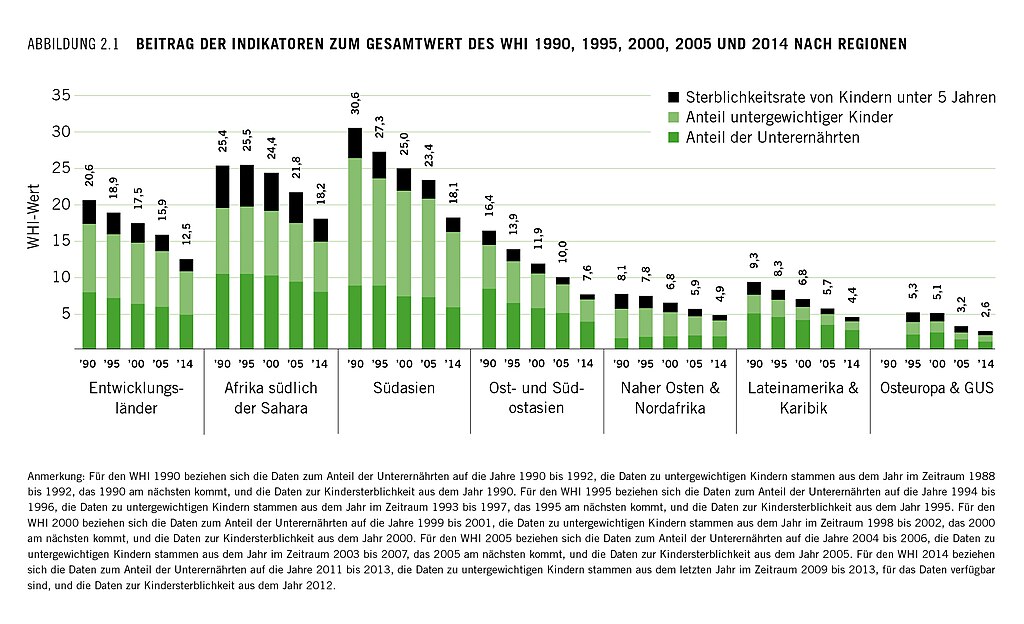

Looking at the major regions of developing countries, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have the highest GHI scores at 30.1 and 29.0, respectively (Fig. 2.1). According to the GHI severity scale, these values represent serious hunger situations, and while the GHI scores in these regions have declined over time, they are still closer to the "very serious" category (35.0-49.9) than the “moderate” category (10.0–19.9).

The Central African Republic and Chad have the highest starvation levels in the report. The two countries have only been able to reduce hunger slightly since 2000. Civil wars and extreme weather events put a heavy strain on food production. Rwanda, Cambodia and Myanmar achieved the highest percentage reduction in values since 2000 of any country with a “serious” or “very serious” hunger situation. Each of the countries cut their 2016 values by a little more than 50 percent compared to 2000.

GHI scores are not available for 13 countries and the available data indicate that 10 of these countries are of serious concern. These include u. a. Burundi, Congo, Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan.

The report shows that great strides have been made in combating hunger and malnutrition in developing countries. At the same time, however, it shows that there are numerous areas in which people are particularly at risk. The lack of data, particularly at the sub-national level, needs to be addressed to ensure that no one is disadvantaged or left behind on the road to a world free of hunger by 2030.

Political recommendations for action

Germany must assume its international responsibility and make its contribution to ensuring that everyone can eat adequately and healthily. To do this, our production and consumption patterns must also change. Among other things, we demand:

- Promote sustainability: The German government and the EU must ensure that their policies promote sustainable nutrition. The ecological and social follow-up costs of factory farming must be borne by the manufacturers and are also reflected in the product price. Consumers would be more likely to choose products from regional and sustainable production.

- Examine the consequences for the right to food: The effects of decisions in all policy areas on food security and the right to food in developing countries must be systematically examined. So should z. For example, in the case of free trade and investment agreements, an independent human rights and ecological impact assessment always takes place.

- Promote social production standards: Agriculture in developing countries must be paid fairly. Our government must advocate binding social standards in the production regions and support their implementation.

GHI 2015

The 2015 Global Hunger Index was published in October 2015. Compared to this year's reference year 2000, the value has improved by 27 percent. Seventeen countries were able to reduce their GHI scores by 50 percent or more compared to 2000. Despite this progress, 795 million people around the world are still starving, every fourth child is restricted in their physical and mental development, and 3.1 million children are still dying of malnutrition. The hunger scores in 50 of 117 countries are still rated as “serious” or “very serious” with GHI scores.

Regional and national trends

Especially in southern Africa, south of the Sahara, many countries have “serious” or “very serious” GHI scores. The Central African Republic and Chad had the highest GHI scores in 2015. The GHI report indicates that many countries with poor scores have been hit by violent conflict, political instability, or war. Since the great civil wars of the 1990s and 2000s ended in countries like Ethiopia, Angola and Rwanda, their hunger levels have fallen considerably. But even countries that are not affected by armed conflict can have high GHI scores, e.g. B. Zambia.

Brazil has made great strides, reducing its GHI score by around two thirds since 2000. The report attributes this to the government's “Zero Hunger” program.

Many countries, which often had high levels of hunger in previous years, could not be included in this year's report due to a lack of data. These include Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, the Comoros, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan.

The chapter on hunger and conflict makes it clear that the number of catastrophic famines (each of which killed more than a million people) seems to be a thing of the past. Nevertheless, since 2006 there has been a renewed increase in wars and armed conflicts. Armed conflict and extreme poverty need to be reduced in order to overcome hunger.

From practice

In the 2015 edition of the Global Hunger Index, two practical examples from Welthungerhilfe and Concern project areas on Mali and South Sudan appear.

Individual records 2015

- ↑ 2015 Global Hunger Index. Hunger and armed conflict . IFPRI / Welthungerhilfe / Concern Worldwide . Bonn / Washington, DC / Dublin 2015, 52 pp.

- ↑ From practice: Case study 2015. Welthungerhilfe .

GHI 2014

The 2014 Global Hunger Index was published in October 2014. This year the report is dedicated to the main topic of micronutrient deficiencies , also known as hidden hunger. In 2014 the total GHI score was 12.5; this means that the total value has decreased by 39 percent compared to the calculated value of 1990. Despite this progress, the number of starving people remains high at 805 million.

Regional and national trends

According to the 2014 Global Hunger Index, hunger is greatest in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia: Sub-Saharan Africa has a GHI score of 18.2 and the GHI score for South Asia is 18.1. According to the World Hunger Index, the nutritional situation in both regions is still “serious”. In East and Southeast Asia, the situation has steadily improved over the past few years, where the GHI value is now 7.6. The hunger situation is now "less" pronounced in the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as in Eastern Europe and the CIS countries.

According to the GHI score, the nutritional situation in two countries is still "serious": Burundi (GHI score 35.6) and Eritrea (GHI score 33.8). In 14 countries the situation is rated as "very serious". These include primarily countries in sub-Saharan Africa as well as Haiti, Laos and Timor-Leste.

Challenge hidden hunger

Over two billion people worldwide are affected by hidden hunger. This micronutrient deficiency occurs when people either don't get enough micronutrients (such as zinc , iodine, and iron ) and vitamins , or the body cannot absorb them. Reasons for this can be an unbalanced diet, an increased need for micronutrients (e.g. during pregnancy and breastfeeding) and health problems due to diseases, infections or parasites.

The consequences for individuals can be devastating: mental impairment, poor health, low productivity, and disease-related deaths. Children in particular are affected by the consequences if they cannot take in enough micronutrients within the first 1000 days of their life from conception to their second birthday. Micronutrient deficiencies are responsible for an estimated 1.1 million of the 3.1 million child deaths caused by malnutrition annually. However, it has not yet been easy to obtain precise data on the spread of hidden hunger.

Global losses in economic productivity due to macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies cause worldwide damage of 1.4 to 2.1 trillion US dollars per year.

Solution approaches for hidden hunger

There are various measures to prevent hidden hunger. It is particularly effective to enable people to have a varied diet. The quality of the food should be just as important as the quantity (pure calorie intake). This can be done, for example, by encouraging the cultivation of a variety of nutrient-rich food crops and creating home gardens. Further approaches are the industrial enrichment (fortification) of foodstuffs or the biofortification of food plants (for example sweet potatoes enriched with vitamin A). In the case of acute nutrient deficiency and in certain phases of life, nutritional supplements (supplementation) should also be considered. Especially the addition of vitamin A leads to an improvement in the survival rate of children. Overall, the situation with regard to hidden hunger can only be improved if many measures are interlinked and, in addition to direct measures to promote better nutrition, also educate and empower women, promote better hygienic conditions, access to clean drinking water and health services be included.

Political recommendations for action

Getting full is not enough. Every man, every woman and every child has the right to culturally appropriate food in sufficient quantities, but also in sufficient quality to meet their nutritional needs. The international community must ensure that hidden hunger is not overlooked and that the post-2015 development agenda includes a comprehensive goal to eradicate hunger and malnutrition of all forms.

- Make eliminating hidden hunger a high priority

- Develop suitable and appropriate political concepts and coordinate them

- Develop nutrition knowledge and skills at all levels by providing human and financial resources

- Strengthening accountability: Governments and international institutions must create a regulatory environment that supports adequate nutrition

- Expand monitoring, research, and the data base to strengthen accountability

Individual records 2014

- ↑ Global Hunger Index 2014. The challenge of hidden hunger . IFPRI / Welthungerhilfe / Concern Worldwide . Bonn / Washington, DC / Dublin 2014, 60 pp.

- ↑ Our daily want. In: Zeit Online . 4th June 2013.

GHI 2013

The 2013 Global Hunger Index was published in October 2013. Its thematic focus is strengthening resilience against malnutrition at the community level. It bears the subtitle: The Hunger Challenge: Strengthening Resilience, Securing Nutrition. With a value of 13.8, the global hunger index signals that the global food situation remains “serious”. In 1990 the global value was 20.8; d. H. the index has fallen by almost 34 percent since then.

Regional and national trends

According to the 2013 Global Hunger Index, hunger continues to be greatest in the South Asia region: with a GHI score of 20.7, the nutritional situation is still “very serious”. Close behind is Africa south of the Sahara with a GHI score of 19.2. Sub-Saharan Africa has thus fallen below the mark of 20 for the first time and the hunger situation there is - albeit just under - classified in the better category of “serious”. In Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, as well as in Latin America and the Caribbean, the food situation is much better: with GHI scores of 2.7 and 4.8, hunger is not very widespread in these regions. The regions of East and Southeast Asia as well as Latin America and the Caribbean have made the greatest progress, with their index values having improved by more than 50 percent since 1990.

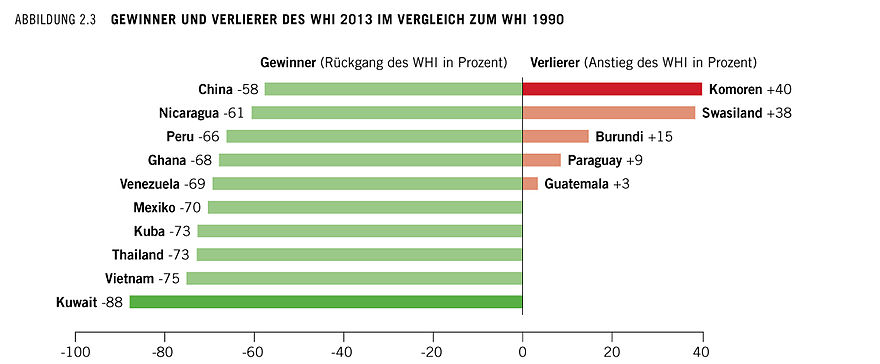

In three countries, Burundi, Eritrea and the Comoros, the food situation is “serious”. In contrast, Thailand and Vietnam, among others, have had great successes in fighting hunger, and both countries have lowered their GHI scores by more than 70 percent since 1990.

Resilience to malnutrition

Many of the countries in which the hunger situation is already “very serious” or “severe” are also particularly vulnerable to crises: in the African Sahel, for example, people experience annual periods of hunger. Both conflicts and natural disasters are an additional burden. At the same time, the global environment is becoming increasingly volatile (financial and economic crisis, food price crisis).

The inability to cope with these crises ensures that hard-earned development successes are undone and people have even fewer resources and capacities to counter the next crisis. For the 2.6 billion people worldwide who have to manage on less than $ 2 a day, a family illness, a drought-related crop failure or an interruption in remittances from their relatives from abroad can set a downward spiral in motion which they can no longer free themselves on their own.

It is therefore not enough to stand by people in emergency situations and - once the crisis is over - to initiate longer-term development measures. Rather, both emergency aid measures and development cooperation must be designed in such a way that they are designed to strengthen people's resistance to these crises [definition of resilience: ability to survive difficult phases in life unscathed].

Conceptually, the Global Hunger Index distinguishes between three different coping strategies. The lower the intensity of the crisis, the less has to be expended to deal with the effects.

- Absorption: skills with which the effects of a crisis are mitigated / absorbed without changing lifestyle habits (e.g. selling some animals from the herd)

- Adaptation: When the abilities to absorb are exhausted, measures to adapt the way of life are gradually carried out without making profound changes (e.g. switching to drought-resistant seeds)

- Transformation: If lifestyle adjustments are not enough to counter the negative effects of a crisis, fundamental, permanent changes in life / behavior must be made (e.g. Normands become sedentary and farm because they no longer keep their cattle can)

Political recommendations for action

- Overcoming the institutional, financial and conceptual boundaries between humanitarian aid and development cooperation.

- Eliminate policies that undermine people's resilience. Orientation towards the right to food when drafting new policies and laws.

- Implementation of multi-year, flexible programs the financing of which enables multisectoral approaches to overcome chronic food crises.

- Communicate that resilience-building measures are cost-effective and improve food security, especially in fragile contexts.

- Scientific monitoring and evaluation of measures and programs that aim to strengthen resilience.

- Active involvement of local people in the planning and implementation of programs aimed at building resilience.

- Improving nutrition, especially for mothers and children, through nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions in order to prevent short-term crises from leading to malnutrition having consequences for later life or being passed on through generations.

GHI 2012

The Global Hunger Index, published in October 2012, deals with the question of how nutrition can be secured in the long term when the natural foundations of nutrition become increasingly scarce. (Hunger challenge: securing food when land, water and energy are scarce). The global hunger index value is 14.7 and thus indicates a "serious" hunger situation. It is true that the proportion of malnourished people worldwide has decreased since 1990 and the index fell by around 26 percent. However, progress has been slow and, in particular, the pace of the fight against hunger has been significantly reduced today compared to the period between 1990 and 1996.

Regional and national trends

According to the Global Hunger Index, hunger is greatest in South Asia: At 22.5, the hunger situation here is "very serious". In sub-Saharan Africa, the index value also exceeds 20 and can be classified as "very serious". The value is lowest in Eastern Europe, where hunger is not very pronounced. In addition to Southeast Asia and Latin America, Eastern Europe also made the greatest progress in fighting hunger. In all three regions, the GHI scores have fallen by 40 percent and more since 1990.

Some countries have made particularly great strides in fighting hunger. These include Turkey, Mexico, China and Ghana, among others. In some countries, however, the hunger situation has also worsened since 1990 (see graph). The hunger situation is grave in 3 countries: Burundi, Eritrea and Haiti top the list of “hungry countries” and, with an index value of over 30.0, indicate a particularly urgent need for action.

Scarce land, water and energy resources

Hunger is increasingly closely related to how we use land, water and energy. If these resources also become scarcer overall , food security will also come under increasing pressure. Several factors contribute to the scarcity of natural resources:

- Demographic change : According to forecasts, the world population will have grown to over 9 billion by 2050. In addition, more people will live in cities in the future. The urban population eats differently; they tend to consume less staple foods and more meat and dairy products are consumed.

- Higher income and unsustainable consumption of resources: global economic power is increasing, wealthy people are consuming more food and goods that are produced with a lot of water and energy. You can afford to be inefficient and wasteful with resources.

- Bad policy and weak institutions: If policy-making, for example in the area of energy, is not checked to determine what consequences it has in terms of land and water availability, this can lead to undesirable developments. An example of this is the biofuel policy of the industrialized countries: If corn and sugar cane are increasingly used to produce fuel, less land and water will be available for food production

Signs that energy, land and water are becoming scarcer include: rising food and energy prices, a massive increase in large-scale investments in agricultural land (so-called " land grabbing "), increasing degradation of arable land due to excessive cultivation (for example increased desertification ), an increasing number of people living in regions with falling water tables, and the loss of agricultural land due to climate change . The authors of the Global Hunger Index derive political recommendations for action from the analysis of the global framework conditions:

- Securing land and water rights .

- Gradual dismantling of subsidies.

- Creation of positive general economic conditions

- Investing in agricultural production technologies that promote more efficient use of land, water and energy.

- Expansion of approaches that lead to more efficient use of land, water and energy along the value chain .

- Prevention of overuse of natural resources through accompanying analysis of water, land and energy strategies as well as agricultural cultivation systems

- Improving women's access to education and strengthening their reproductive rights to face demographic change.

- Increase income, reduce social and economic inequality and promote sustainable lifestyles.

- Mitigation of climate change and adaptation to the consequences through a corresponding reorientation of agriculture

GHI 2011

The 2011 Global Hunger Index, published in October of that year, bears the subtitle The Hunger Challenge: How Rising and Fluctuating Food Prices Exacerbate Hunger .

Compared to 2010, the global GHI value fell from 15.1 to 14.6 (in 1990: 19.7). According to the report, this decline is primarily due to the improved nutritional situation of children under five, whose proportion of all children under five has declined by 8 percent since 1990. During the same period, child mortality fell by 3 percent. The proportion of undernourished people in the world population has remained almost unchanged since 1995–1997; since 1990 it has decreased by 4 percent. The decrease in the global GHI and thus the improvement in the nutritional situation between 1990 and 1996 was the greatest, by a total of 3.

The Global Hunger Index pays special attention to the countries in which there is an urgent need for action and thus sees itself as a basis for advice on policy-making and advocacy work at national and international level.

Regional trends

Compared to 1990, the GHI declined 18 percent in sub-Saharan Africa , about 25 percent in South Asia , and 39 percent in the Middle East and North Africa . Regional advances were greatest in Southeast Asia , Latin America and the Caribbean , with reductions of more than 44 percent each. Compared to 1996, that in Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States fell by 47 percent.

The highest regional value is recorded in South Asia, where the GHI has barely declined after falling sharply from 1990 to 1996 despite economic growth since 2001. Progress is hindered, according to the report, by social inequality and the low nutritional, educational and social status of women. The somewhat smaller improvements in sub-Saharan Africa can be traced back to the end of several conflicts in Africa in the 1990s and 2000s, economic growth and successes in the fight against AIDS .

Rising and fluctuating food prices

The report sees the increasing (n) increase in food prices as three main causes of high volatility , i.e. price fluctuations and price increases

- Use of so-called biofuels (“competition between plate and tank”), promoted by high oil prices , subsidies in the United States (over a third of the respective corn harvests in 2009 and 2010) and admixture quotas in the European Union, India and the like. a.

- extreme weather events as a result of climate change

- Goods were forward transactions with agricultural goods, examples being given are increasing investments in funds that speculate on agricultural products (2003: 13 billion US dollars, 2008: 260 billion US dollars), as well as the increasing trading volumes of these goods

According to the report, volatility and price increases are exacerbated by the concentration of exports of basic foodstuffs in a few countries and their export restrictions , the historic low in global grain reserves and the frequent unavailability of up-to-date information on food production, stocks and price developments, which provoke overreactions among market participants . In addition, there are seasonal restrictions on production possibilities, limited cultivation and grazing areas, and limited availability of nutrients and water, as well as increasing demand as a result of population growth, which puts pressure on food prices.

According to the 2011 Global Hunger Index, price trends have particularly serious consequences for poor and starving people because they are barely able to react to price spikes and rapid price fluctuations. Actions as a result of such developments can include: reduced caloric intake, no longer sending children to school, risky income opportunities such as prostitution , crime and searching garbage dumps and sending away household members who can no longer be fed. In addition, the report currently sees an all-time high in the instability and unpredictability of food prices, which, after decades of slight decline, are now showing frequent price spikes (sharp and short-term increases).

At the national level, importing countries are particularly affected by price fluctuations, i.e. those with a negative food trade balance .

Political recommendations for action

- Review and, if necessary, suspension of blending quotas and subsidies for biofuels

- Regulation of financial activities in food markets in the form of stricter reporting requirements , higher deposit capital - minimum share for short-term futures transactions and tightening of quantity and price limits for trading in agricultural commodity derivatives

- Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

- better preparation for extreme weather events

- poverty-oriented increase in agricultural production, which should enable more countries to export basic foodstuffs

- international food reserves

- Improved access of market participants to relevant information, examples given are the existing Famine Early Warning Systems Network and the agricultural market information system planned by the G-20

- Worldwide dissemination of functioning basic social security systems at national level

- Promotion of income opportunities outside of agriculture

- Improving training opportunities for the poor in cities

- Small-scale , sustainable and climate-adapted agriculture

- improved crisis management even when hunger crises slowly set in, analogous to disaster control

Individual records 2011

- ^ Klaus von Grebmer, Maximo Torero, Tolulope Olofinbiyi, Heidi Fritschel, Doris Wiesmann, Yisehac Yohannes ( IFPRI ); Lilly Schofield, Constanze von Oppeln ( Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe ): Welthunger-Index. Hunger challenge: How rising and fluctuating food prices exacerbate hunger . Bonn / Washington, DC / Dublin 2011, 68 pp.

- ↑ Chapter 3: High and volatile food prices exacerbate hunger and Chapter 4: The effects of price peaks and volatility at the local level , p. 21 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as broken. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. -45.

GHI 2010

Progress is slow

The 2010 Global Hunger Index was published in October of that year and is subtitled The Hunger Challenge. The chance of the first 1000 days , which refers to a child's first 1000 days after conception . The report focuses on the nutritional situation of children of this age.

Globally, the GHI score fell from 19.8 to 15.1 between 1990 and 2010. According to the report, global food security is “further away than ever”. Compared to the UN Millennium Development Goals for 2015, progress in the fight against hunger is slow. The report cites an estimate by the FAO that the number of undernourished people will fall from one billion (2009) to 925 million (2010).

Global and regional trends

In 2010, the GHI was determined for 122 developing and emerging countries . 84 of them were classified in a ranking, the remaining 38 countries, which had a GHI of below 5 (“little hunger”) in both 1990 and 2010, were not included.

When comparing the 1990 and 2010 GHI indices, few countries made significant progress and reduced their global hunger index by 50 percent or more. At the same time, about a third of countries made modest progress, dropping their GHI scores by 25 to 49.9 percent. Another third were able to improve their GHI scores by 0 to 24.9 percent.

Some states are highlighted in the report:

- Kuwait : The biggest drop in the GHI is attributed to the poor nutritional situation in 1990, when Iraqi troops invaded .

- Malaysia comes in second best and achieved a "huge reduction in the proportion of underweight children" from 22.1% (1990) to 7% (2005). The 2010 GHI refers to a paper by Martin Khor , which this success to rapid economic growth returns and measures of the government, such as "food aid for economically disadvantaged families with malnourished children, programs for food supplementation for preschool and primary blame children, the issue of micronutrients to Pregnant women and the implementation of information events on proper nutrition. "

- Democratic Republic of the Congo : The GHI value is highest here at 41.0, and the largest increase since 1990 at more than 65%. The state has one of the highest child mortality rates in the world and an undernourished proportion of the total population of over 75%. This is attributed to protracted civil wars since the 1990s , low food production and regions isolated by poor infrastructure.

- Ghana is the only sub-Saharan African country to lower its GHI by more than 50 percent; it is the only country in the region to be among the ten countries that have improved their GHI the most since 1990. In addition to Kuwait, Malaysia and Ghana, Turkey , Mexico , Tunisia , Nicaragua , Iran , Saudi Arabia and Peru also achieved significant improvements .

- Negative developments can be seen not only in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but also in several other African countries, above all in the Comoros , Burundi , Swaziland and Zimbabwe , as well as in North Korea .

Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have the highest regional GHI scores (21.7 and 22.9, respectively). The precarious food situation in both regions is due to different causes: In South Asia, underweight children under five are the most important factor. This is largely due to the poor nutritional and educational status of women. In contrast, the high GHI in Sub-Saharan Africa is explained by the high child mortality rate and the high proportion of people who cannot meet their calorie needs. This is mainly due to bad governance, conflict, political instability and high HIV and AIDS rates.

Individual results:

- Over half of the total population in Burundi , the Democratic Republic of the Congo , Eritrea , the Comoros and Haiti is malnourished.

- The countries with serious GHI scores (≥ 30) are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Eritrea and Chad .

- More than 40 percent of children in Bangladesh , India , Yemen and East Timor are malnourished.

- The under-5 mortality rate in Afghanistan , Angola , Somalia and Chad is over 20 percent.

Compared to 1990, the GHI declined 14 percent in sub-Saharan Africa , about 25 percent in South Asia , and 33 percent in the Middle East and North Africa . Regional advances were greatest in Southeast Asia , Latin America and the Caribbean , with reductions of more than 40 percent each.

The 2010 Global Hunger Index also compares the regional change in the poverty situation with its GHI score: In South Asia, the region with the highest number of people living in poverty, the decrease in poverty is proportional to the decrease in the GHI score. In Southeast Asia, poverty has decreased by 8 percent since 1990, while the GHI has decreased by 3 percent. In Latin America and the Caribbean, however, poverty decreased 1 percent, while the GHI decreased 3.5 percent.

Early childhood malnutrition

The 2010 Global Hunger Index sees the population group of small children as being particularly at risk of hunger and points to the particular life- threatening and long-term consequential damage of poor nutrition in the first two years of life. In developing countries around 195 million children under five - around a third of all children worldwide - are too small for their age and therefore underdeveloped. Almost a quarter of those under five, 129 million, are underweight and a tenth are severely underweight. Over 90 percent of underdeveloped children live in Africa and Asia. 42 percent of all underweight children worldwide live in India alone.

According to the Global Hunger Index, the decisive action window for combating early childhood malnutrition covers the period from −9 to +24 months, i.e. the 1000 days between conception and the completion of the second year of life. Children who were inadequately nourished in the first 1000 days of their life can suffer permanent damage, such as impaired physical and mental development, a weak immune system and even lower life expectancy . After the age of two, the effects of malnutrition are largely reversible .

Political recommendations for action

On the basis of the published material, the editors of the WHI index give a number of recommendations for action:

- Priority of nutrition in political decisions

- Combating indirect causes of malnutrition, for example through agricultural and social security programs that particularly affect the “poorest of the poor”

- Targeted nutritional interventions for pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under 2 years of age, which are "based on already successful methods and local conditions": Promotion of healthy breastfeeding practices, adequate vaccination , adequate complementary food , iodized salt consumption and the availability of dietary supplements as required like vitamin A and zinc .

- Promotion of equality for women , as the 2010 GHI sees a close connection between their disadvantage and poor nutrition. a. appeals to various authors; In particular, the food security of girls and young women should be achieved with the help of programs "that deal with health, nutrition, education and social security in adolescence and early adulthood"

Individual evidence 2010

- ↑ Klaus von Grebmer, Marie T. Ruel, Purnima Menon, Bella Nestorova, Tolulope Olofinbiyi, Heidi Fritschel, Yisehac Yohannes ( IFPRI ); Constanze von Oppeln, Olive Towey, Kate Golden, Jennifer Thompson ( Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe ): 2010 Welthunger-Index. Hunger Challenge: The Chance of the First 1,000 Days. Bonn / Washington, DC / Dublin 2010, 60 pp. (PDF; 3.8 MB).

- ↑ 2010 Global Hunger Index. Preface.

- ↑ 2010 Global Hunger Index. P. 13.

- ↑ a b c 2010 Global Hunger Index. P. 45.

literature

WHIs 2006–2019 in the edition in German and English, available on the website of the world hunger index globalhungerindex.org :

- 2006 - wars exacerbate hunger - ten African countries bring up the rear

- 2007 - One third of the countries on track, Africa remains the focus

- 2008 - 33 countries have very serious to severe hunger situations

- 2009 - How the financial crisis aggravates hunger and why women matter

- 2010 - Hunger Challenge: The Chances of the First Thousand Days

- 2011 - How rising and fluctuating food prices exacerbate hunger

- 2012 - The Hunger Challenge: Securing Food When Land, Water and Energy Are Scarce

- 2013 - The Hunger Challenge: Strengthening Resilience, Securing Food

- 2014 - The hidden hunger challenge

- 2015 - hunger and armed conflict

- 2016 - The commitment to end hunger

- 2017 - How inequality creates hunger

- 2018 - Flight, displacement and hunger

- 2019 - How climate change aggravates hunger

Web links

- Global Hunger Index website

- Welthungerhilfe's World Hunger Index topic page

- Global Hunger Index: current data, background, Agenda 21 meeting point

Individual evidence

- ↑ Current results. Trends: global, regional, national. In: Global Hunger Index. Accessed on October 31, 2019 (expert report with current hunger figures).

- ↑ Topics. In: Global Hunger Index. Accessed on October 31, 2019 (expert report with current hunger figures).

- ^ Comparisons of hunger across states. In: IFPRI Publications. Retrieved October 31, 2018 .

- ^ A sub-national hunger index for Ethiopia. IFPRI, accessed October 31, 2018 .

- ↑ About the WHI. The concept of the global hunger index. In: Global Hunger Index. Retrieved October 31, 2018 .

- ^ The Concept of the Global Hunger Index . Global Hunger Index. Retrieved November 12, 2019.