Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi and Aspirin: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{drugbox | |

|||

{{future film}} |

|||

| IUPAC_name = 2-ethanoylhydroxybenzoic acid |

|||

{{Infobox Film |

|||

| image = Aspirin-skeletal.svg |

|||

| name = Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi |

|||

| image2 = Aspirin-B-3D-balls.png |

|||

| Image:Rab Ne Bana di jodi.JPG |

|||

| |

| width = 150 |

||

| |

| width2 = 150 |

||

| CAS_number = 50-78-2 |

|||

| director = [[Aditya Chopra]] |

|||

| ChemSpiderID = 2157 |

|||

| producer = [[Aditya Chopra]]<br />[[Yash Chopra]] |

|||

| ATC_prefix = A01 |

|||

| writer = [[Aditya Chopra]] |

|||

| ATC_suffix = AD05 |

|||

| starring =[[Shahrukh Khan]]<br />[[Anushka Sharma]] |

|||

| ATC_supplemental = {{ATC|B01|AC06}}, {{ATC|N02|BA01}} |

|||

| music = [[Salim-Sulaiman]] |

|||

| PubChem = 2244 |

|||

| cinematography = |

|||

| |

| DrugBank = APRD00264 |

||

| C=9 | H=8 | O=4 |

|||

| distributor = [[Yash Raj Films]] |

|||

| molecular_weight = 180.160 g/mol |

|||

| released = [[December 12]], [[2008]] |

|||

| smiles = CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O |

|||

| runtime = |

|||

| synonyms = 2-acetyloxybenzoic acid<br />2-(acetyloxy)benzoic acid<br />acetylsalicylate<br />acetylsalicylic acid<br />O-acetylsalicylic acid |

|||

| country = {{IND}} |

|||

| |

| density = 1.40 |

||

| melting_point = 135 |

|||

| budget = |

|||

| boiling_point = 140 |

|||

| gross = |

|||

| boiling_notes = (decomposes) |

|||

| preceded_by = |

|||

| |

| solubility = 10 |

||

| bioavailability = Rapidly and completely absorbed |

|||

| website = |

|||

| protein_bound = 99.6% |

|||

| imdb_id = 1182937 |

|||

| metabolism = [[Liver|Hepatic]] |

|||

| elimination_half-life = 300–650 mg dose: 3.1–3.2hrs<br />1 g dose: 5 hours<br />2 g dose: 9 hours |

|||

| excretion = [[Kidney|Renal]] |

|||

| pregnancy_AU = C |

|||

| pregnancy_US = C |

|||

| legal_AU = unscheduled |

|||

| legal_CA = |

|||

| legal_UK = GSL |

|||

| legal_US = OTC |

|||

| legal_status = |

|||

| routes_of_administration = Most commonly oral, also rectal. [[Lysine acetylsalicylate]] may be given [[intravenous therapy|IV]] or [[intramuscular injection|IM]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Aspirin''', or '''acetylsalicylic acid (A.S.A.)''' ({{IPAEng|əˌsɛtɨlsælɨˌsɪlɨk ˈæsɨd}}), is a [[salicylate]] [[medication|drug]], often used as an [[analgesic]] to relieve minor aches and pains, as an [[antipyretic]] to reduce [[fever]], and as an [[anti-inflammatory]] medication. |

|||

In countries where Aspirin is a registered [[trademark]] owned by [[Bayer]], the generic term is "A.S.A." |

|||

'''''Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi''''' is a forthcoming [[Cinema of India|Indian]] [[Bollywood]] film that stars [[Shahrukh Khan]] and newcomer [[Anushka Sharma]] in pivotal roles.<ref>{{cite web|author=Adarsh, Taran|title=Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi|url=http://www.indiafm.com/news/2008/02/01/10820/index.html|publisher=[[Indiafm.com]]|accessdate=2008-05-16}}</ref> Directed by [[Aditya Chopra]], who earlier directed hits like ''[[Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge]]'' (1995) and ''[[Mohabbatein]]'' (2000), the film is currently in its filming stage and is expected to release on [[December 12]], [[2008]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Yash Raj Films’ incredible line-up for 2008|url=http://www.yashrajfilms.com/News/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsID=3e73203f-bf57-4fd2-86b6-b6cb48e4b513|publisher=[[Yash Raj Films]]|accessdate=2008-03-15}}</ref> |

|||

Aspirin also has an [[Antiplatelet drug|antiplatelet]] or "anti-clotting" effect and is used in long-term, low doses to prevent [[myocardial infarction|heart attacks]], [[stroke]]s and [[thrombus|blood clot]] formation in people at high risk for developing blood clots.<ref>{{Cite journal| issn = 00284793| volume = 309| issue = 7| pages = 396–403| last = Lewis| first = H D |

|||

==Production== |

|||

| coauthors = J W Davis, D G Archibald, W E Steinke, T C Smitherman, J E Doherty, H W Schnaper, M M LeWinter, E Linares, J M Pouget, S C Sabharwal, E Chesler, H DeMots| title = Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study| journal = The New England journal of medicine| date = 1983-08-18}}</ref> It has also been established that low doses of aspirin may be given immediately after a heart attack to reduce the risk of another heart attack or of the death of cardiac tissue.<ref name="anticoag">{{cite journal | last = Julian | first = D G | coauthors = D A Chamberlain, S J Pocock | title = A comparison of aspirin and anticoagulation following thrombolysis for myocardial infarction (the AFTER study): a multicentre unblinded randomised clinical trial | journal = BMJ| volume = 313 | issue = 7070 | pages = 1429–1431 | publisher = British Medical Journal | date = 1996-09-24| url = http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/313/7070/1429 | accessdate = 2007-10-04 | pmid = 8973228}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| volume = 92| issue = 10| pages = 2841–2847| last = Krumholz| first = Harlan M.| coauthors = Martha J. Radford, Edward F. Ellerbeck, John Hennen, Thomas P. Meehan, Marcia Petrillo, Yun Wang, Timothy F. Kresowik, Stephen F. Jencks| title = Aspirin in the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries : Patterns of Use and Outcomes| journal = Circulation| accessdate = 2008-05-15| date = 1995-11-15| url = http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/92/10/2841| pmid = 7586250}}</ref> |

|||

The film commenced shooting on [[May 16]], [[2008]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Shah Rukh Khan starts shooting for Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi|url=http://www.indiafm.com/news/2008/05/16/11395/index.html|publisher=[[Indiafm.com]]|accessdate=2008-05-16}}</ref> |

|||

The main [[adverse drug reaction|undesirable side effects]] of aspirin are [[gastrointestinal]]—[[gastric ulcer|ulcers]] and stomach bleeding—and [[tinnitus]], especially in higher doses. In children under 19 years of age, aspirin is no longer used to control [[Influenza|flu]]-like symptoms or the symptoms of [[chickenpox]], due to the risk of [[Reye's syndrome]].<ref name="BMJ2002-Macdonald">{{cite journal | author=Macdonald S | title=Aspirin use to be banned in under 16 year olds | journal=BMJ | volume=325 | issue=7371 | pages=988 | year=2002 | pmid= 12411346 |pmc=1169585 | doi=10.1136/bmj.325.7371.988/c}}</ref> |

|||

==Cast== |

|||

* [[Shahrukh Khan]] |

|||

* [[Anushka Sharma]] |

|||

* [[Vinay Pathak]] |

|||

*[[Anupam Kher]] |

|||

*[[Farida Jalal]] |

|||

* [[Kajol]] |

|||

Aspirin was the first-discovered member of the class of drugs known as [[non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs]] (NSAIDs), not all of which are salicylates, although they all have similar effects and most have some [[Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs#Mode of action|mechanism of action]] which involves non-selective inhibition of the enzyme [[cyclooxygenase]]. Today, aspirin is one of the most widely used medications in the world, with an estimated 40,000 [[metric tons]] of it being consumed each year.<ref name='cox3article'> {{cite journal|title=Cyclooxygenase-3 (COX-3): filling in the gaps toward a COX continuum?|journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a|date=2002-10-15|first=|last=|coauthors=Warner TD, Mitchell JA.|volume=99|issue=21|pages=13371–3|pmid=12374850 |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/extract/99/21/13371|accessdate=2008-05-08|doi=10.1073/pnas.222543099|author=Warner, T. D. }}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== History == |

|||

{{Main|History of aspirin}} |

|||

Medicines containing derivatives of [[salicylic acid]], structurally similar to aspirin, have been in medical use since ancient times. [[Salicylate]]-rich [[willow]] bark extract became recognized for its specific effects on fever, pain and inflammation in the mid-eighteenth century. By the nineteenth century pharmacists were experimenting with and prescribing a variety of chemicals related to [[salicylic acid]], the active component of willow extract. |

|||

A French chemist, [[Charles Frederic Gerhardt]], was the first to prepare acetylsalicylic acid (named aspirin in 1899) in 1853. In the course of his work on the synthesis and properties of various [[acid anhydride]]s, he mixed [[acetyl chloride]] with a [[sodium]] salt of salicylic acid (sodium salicylate). A vigorous reaction ensued, and the resulting melt soon solidified.<ref name=gerhardt>{{de icon}} {{cite journal |author=Gerhardt C |title=Untersuchungen über die wasserfreien organischen Säuren |journal=Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie|volume=87 |issue= |pages=149–179 |year=1853 |doi=10.1002/jlac.18530870107}}</ref> Since no structural theory existed at that time, Gerhardt called the compound he obtained "salicylic-acetic anhydride" (''wasserfreie Salicylsäure-Essigsäure''). This preparation of aspirin ("salicylic-acetic anhydride") was one of the many reactions Gerhardt conducted for his paper on anhydrides, and he did not pursue it further. |

|||

[[Image:BayerHeroin.png|thumb|right|180px|Advertisement for Aspirin, Heroin, Lycetol, Salophen]] |

|||

Six years later, in 1859, von Gilm obtained analytically pure acetylsalicylic acid (which he called "acetylierte Salicylsäure", ''acetylated salicylic acid'') by a reaction of salicylic acid and acetyl chloride.<ref name=gilm>{{de icon}} {{cite journal |author=von Gilm H |title=Acetylderivate der Phloretin- und Salicylsäure |journal=Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie|volume=112 |issue=2 |pages=180–185 |year=1859 |doi=10.1002/jlac.18591120207}}</ref> In 1869 Schröder, Prinzhorn and Kraut repeated both Gerhardt's (from sodium salicylate) and von Gilm's (from salicylic acid) syntheses and concluded that both reactions gave the same compound—acetylsalicylic acid. They were first to assign to it the correct structure with the acetyl group connected to the phenolic oxygen.<ref>{{de icon}} {{cite journal |author= Schröder, Prinzhorn, Kraut K |title=Uber Salicylverbindungen |journal=Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie|volume=150 |issue=1 |pages=1–20 |year=1869 |doi=10.1002/jlac.18691500102}}</ref> |

|||

In 1897, scientists at the drug and dye firm [[Bayer]] began investigating acetylsalicylic acid as a less-irritating replacement for standard common salicylate medicines. By 1899, Bayer had dubbed this drug ''Aspirin'' and was selling it around the world.<ref>{{cite book | last = Jeffreys | first = Diarmuid | title = Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug | publisher = Bloomsbury USA | date = August 11, 2005 | pages = 73 | isbn = 1582346003 }}</ref>The name Aspirin is derived from A = Acetyl and "Spirsäure" = an old (German) name for salicylic acid.<ref>Ueber Aspirin. Pflügers Archiv : European journal of physiology, Volume: 84, Issue: 11-12 (March 1, 1901), pp: 527-546.</ref> Aspirin's popularity grew over the first half of the twentieth century, spurred by its effectiveness in the wake of [[Spanish flu pandemic]] of 1918, and aspirin's profitability led to fierce competition and the proliferation of aspirin brands and products, especially after the American patent held by Bayer expired in 1917.<ref>Jeffreys, ''Aspirin'', pp. 136-142 and 151-152</ref><ref>http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=VideoArticle&id=52415</ref> |

|||

As part of war reparations following Germany's surrender after [[World War I]], Aspirin lost its status as a registered trademark in [[France]], [[United Kingdom]] and the [[United States]] where it became a generic name.<ref>http://www.ul.ie/~childsp/CinA/Issue59/TOC43_Aspirin.htm</ref> Aspirin remains a registered trademark of Bayer in Germany and in over 80 other countries.<ref>http://www.aspirin.com/faq_en.html</ref> |

|||

Aspirin's popularity declined after the market releases of [[paracetamol]] (acetaminophen) in 1956 and [[ibuprofen]] in 1969.<ref>Jeffreys, ''Aspirin'', pp. 212-217</ref> In the 1960s and 1970s, John Vane and others discovered the basic mechanism of aspirin's effects, while clinical trials and other studies from the 1960s to the 1980s established aspirin's efficacy as an anti-clotting agent that reduces the risk of clotting diseases.<ref>Jeffreys, ''Aspirin'', pp. 226-231</ref> Aspirin sales revived considerably in the last decades of the twentieth century, and remain strong in the twenty-first, thanks to widespread use as a preventive treatment for [[heart attack]]s and [[stroke]]s.<ref>Jeffreys, ''Aspirin'', pp. 267-269</ref> |

|||

== Therapeutic uses == |

|||

Aspirin is one of the most frequently used drugs in the treatment of mild to moderate pain, including that of [[migraine]]s and [[fever]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Aukerman G, Knutson D, Miser WF |title=Management of the acute migraine headache |journal=Am Fam Phys |volume=66 |issue=11 |pages=2123–30 |year=2002 |

|||

|pmid=12484694 |url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20021201/2123.html}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| volume = 286| issue = 6372| last = Addy| first = D P| title = Cold comfort for hot children| journal = British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.)| date = 1983-04-09}}</ref> It is often combined with other [[non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug]]s and [[opioid analgesic]]s in the treatment of moderate to severe pain.<ref name="R Barkin">{{cite journal | last = Barkin | first = Robert | title = Acetaminophen, Aspirin, or Ibuprofen in Combination Analgesic Products | journal = American Journal of Therapeutics | volume = 8 | issue = 6 | pages = 433–42 | date = November/December 2001 | url = http://www.americantherapeutics.com/pt/re/ajt/abstract.00045391-200111000-00008.htm;jsessionid=LbQGQ3kCysg2DRjQQ5FhndrgfbXyp1vcpSqhhSP7prKz48H611H5!1379360954!181195629!8091!-1| accessdate = 2008-05-02 | doi = 10.1097/00045391-200111000-00008}}</ref> |

|||

In high doses, aspirin and other salicylates are used in the treatment of [[rheumatic fever]], [[arthritis|rheumatic arthritis]], and other inflammatory joint conditions. In lower doses, aspirin also has properties as an inhibitor of [[platelet]] aggregation, and has been shown to decrease the incidence of transient ischemic attacks and unstable [[Angina pectoris|angina]] in men, and can be used prophylactically. It is also used in the treatment of [[pericarditis]], [[coronary artery disease]], and acute [[myocardial infarction]].<ref> {{cite journal|title=Aspirin in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Patterns of use and outcomes|journal=Circulation|date=1995 November 15|first=HM|last=Krumholz|coauthors=Radford MJ, Ellerbeck EF, Hennen J, Meehan TP, Petrillo M, Wang Y, Kresowik TF, Jencks SF.|volume=92|issue=10|pages=2841–7|pmid=7586250 |url=http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/92/10/284|accessdate=2008-05-02 }}</ref><ref name="Lancet1988-ISIS2">{{cite journal | author=ISIS-2 Collaborative group | title=Randomized trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2 | journal=Lancet | year=1988 | pages=349–60 | issue=2 | pmid= 2899772}}</ref> Low doses of aspirin are also recommended for the prevention of [[stroke]], and myocardial infarction in patients with either diagnosed coronary artery disease or who have an elevated risk of [[cardiovascular disease]]. |

|||

===Experimental uses=== |

|||

[[Image:Acetylsalicylicacid-crystals.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Aspirin in its pure state]] |

|||

Aspirin has been theorized to reduce [[cataract]] formation in diabetic patients, but one study showed it was ineffective for this purpose.<ref name="chew">{{cite journal |author=Chew EY, Williams GA, Burton TC, Barton FB, Remaley NA, Ferris FL |title=Aspirin effects on the development of cataracts in patients with diabetes mellitus. Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study report 16 |journal=Arch Ophthalmol |volume=110 |issue=3 |pages=339–42 |year=1992 |pmid=1543449 |doi=}}</ref> The role of aspirin in reducing the incidence of many forms of [[cancer]] has also been widely studied. In several studies, aspirin use did not reduce the incidence of [[prostate|prostate cancer]].<ref>{{cite journal | author=Bosetti, ''et al.'' | title=Aspirin and the risk of prostate cancer | journal=Eur J Cancer Prev | year=2006 | pages=43–5 | volume=15 | issue=1 | pmid= 16374228 | doi=10.1097/01.cej.0000180665.04335.de}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Menezes, ''et al.'' | title=Regular use of aspirin and prostate cancer risk (United States) | journal=Cancer Causes & Control | year=2006 | pages=251–6 | volume=17 | issue=3 | pmid= 16489532 |doi=10.1007/s10552-005-0450-z}}</ref> Its effects on the incidence of pancreatic cancer are mixed; one study published in 2004 found a statistically significant increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer among women,<ref>{{cite journal | author=Schernhammer, ''et al.'' | title=A Prospective Study of Aspirin Use and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Women | journal=J Natl Cancer Inst | year=2004 | pages=22–28 | volume=96 | issue=1 | pmid= 14709735 | url=http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/96/1/22 | doi=10.1093/jnci/djh001}}</ref> while a meta-analysis of several studies, published in 2006, found no evidence that aspirin or other NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk for the disease.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Bergkvist L, Wolk A |title=Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis |journal=Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. |volume=15 |issue=12 |pages=2561–4 |year=2006 |month=December |pmid=17164387 |doi=10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0574 |url=http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/15/12/2561}}</ref> The drug may be effective in reduction of risk of various cancers, including those of the [[colon cancer|colon]],<ref name="thun">{{cite journal |author=Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Heath CW |title=Aspirin use and reduced risk of fatal colon cancer |journal=[[New England Journal of Medicine|N Engl J Med]] |volume=325 |issue=23 |pages=1593–6 |year=1991 |pmid=1669840 |doi=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Baron, ''et al.'' | title=A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas | journal=N Engl J Med | year=2003 | pages=891–9 | volume=348 | issue=10 | pmid=12621133 | doi=10.1056/NEJMoa021735}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Chan, ''et al.'' | title=A Prospective Study of Aspirin Use and the Risk for Colorectal Adenoma | journal=Ann Intern Med | year=2004 | pages=157–66 | volume=140 | issue=3 | pmid= 14757613}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Chan, ''et al.'' | title=Long-term Use of Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Colorectal Cancer | journal=JAMA | year=2005 | pages=914–23 | volume=294 | issue=8 | pmid= 16118381 | doi=10.1001/jama.294.8.914}}</ref> [[lung cancer|lung]],<ref>{{cite journal | author=Akhmedkhanov, ''et al.'' | title=Aspirin and lung cancer in women | journal=Br J cancer | year=2002 | pages=1337–8 | volume=87 | issue=11 | pmid= 12085255 | doi=10.1038/sj.bjc.6600370}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Moysich KB, Menezes RJ, Ronsani A, ''et al'' |title=Regular aspirin use and lung cancer risk |journal=BMC Cancer |volume=2 |issue= |pages=31 |year=2002 |pmid=12453317 |doi=}} [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/2/31 Free full text]</ref> and possibly the upper GI tract, though some evidence of its effectiveness in preventing cancer of the upper GI tract has been inconclusive.<ref name='Asprin upper GI cancer'> {{cite journal|title=Regular aspirin use and esophageal cancer risk|journal=Int J Cancer|date=2006-07-01|first=|last=|coauthors=Jayaprakash V, Menezes RJ, Javle MM, McCann SE, Baker JA, Reid ME, Natarajan N, Moysich KB.|volume=119|issue=1|pages=202–7|pmid=16450404 |doi=10.1002/ijc.21814|author=Jayaprakash, Vijayvel }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Bosetti, ''et al.'' | title=Aspirin use and cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract | journal=Br J Cancer | year=2003 | pages=672–74 | volume=88 | issue=5 | pmid= 12618872 | doi=10.1038/sj.bjc.6600820}}</ref><ref name='Asprin upper GI cancer'/> Its preventative effect against adenocarcinomas may be explained by its inhibition of [[Cyclooxygenase|COX-2]] enzymes expressed in them.<ref>{{cite journal | author=Wolff, ''et al.'' | title=Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human lung carcinoma | journal=Cancer Research | year=1998 | pages=4997–5001 | volume=58 | issue=22 | url=http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/58/22/4997 | pmid=9823297}}</ref> An older study{{Fact|date=August 2008}} claimed that aspirin may reduce the neurotoxicity of [[THC]], the active drug in [[cannabis]]. However, this theory has been discredited, as newer studies{{Fact|date=August 2008}} indicate THC to be [[neuroprotective]] rather than [[neurotoxic]]. |

|||

===Veterinary uses=== |

|||

Aspirin has been used to treat pain and arthritis in veterinary medicine, primarily in [[cat]]s and [[dog]]s, although it is often not recommended for this purpose, as there are newer medications available with fewer side effects in these animals. Dogs, for example, are particularly susceptible to the gastrointestinal side effects associated with salicylates.<ref>{{cite web | last = Crosby | first = Janet Tobiassen | title = Veterinary Questions and Answers | publisher = About.com | year = 2006 | url = http://vetmedicine.about.com/cs/altvetmedgeneral/a/dogcataspirin.htm | accessdate = 2007-09-05}}</ref> [[Horse]]s have also been given aspirin for pain relief, although it is not commonly used due to its relatively short-lived analgesic effects. Horses are also fairly sensitive to the gastrointestinal side effects. Nevertheless, it has shown promise in its use as an [[anticoagulant]], mostly in cases of [[laminitis]].<ref name="CambridgeH">{{cite journal |author=Cambridge H, Lees P, Hooke RE, Russell CS |title=Antithrombotic actions of aspirin in the horse |journal=Equine Vet J |volume=23 |issue=2 |pages=123–7 |year=1991 |pmid=1904347 |doi=}}</ref> Aspirin should only be used in animals under the direct supervision of a [[veterinarian]]. |

|||

== Mechanism of action == |

|||

{{main|Mechanism of action of aspirin}} |

|||

[[Image:COX-2 inhibited by Aspirin.png|thumb|Structure of COX-2 inactivated by Aspirin. In the active site of each of the two monomers, Serine 530 has been acetylated. Also visible is the salicylic acid which has transferred the acyl group, and the heme cofactor.]] |

|||

In 1971, British [[pharmacologist]] [[John Robert Vane]], then employed by the [[Royal College of Surgeons]] in London, showed that aspirin suppressed the production of [[prostaglandin]]s and [[thromboxane]]s.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs | author = John Robert Vane| journal = Nature - New Biology| year = 1971| volume = 231| issue = 25| pages = 232–5| pmid= 5284360}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Vane JR, Botting RM |month=June |year=2003 |title=The mechanism of action of aspirin |journal=Thromb Res |volume=110 |issue=5-6 |pages=255–8 |pmid=14592543 |doi=10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00379-7 |url=http://www.eao.chups.jussieu.fr/polys/certifopt/saule_coxib/theme/1vane2003.pdf}}</ref> For this discovery, he was awarded both a [[Nobel Prize]] in [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Physiology or Medicine]] in 1982 and a [[knighthood]]. |

|||

Aspirin's ability to suppress the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes is due to its irreversible inactivation of the [[cyclooxygenase]] (COX) enzyme. Cyclooxygenase is required for prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis. Aspirin acts as an acetylating agent where an acetyl group is covalently attached to a [[serine]] residue in the active site of the COX enzyme. This makes aspirin different from other NSAIDs (such as [[diclofenac]] and [[ibuprofen]]), which are reversible inhibitors. |

|||

Low-dose, long-term aspirin use irreversibly blocks the formation of [[thromboxane A2|thromboxane A<sub>2</sub>]] in [[platelet]]s, producing an inhibitory effect on [[platelet|platelet aggregation]]. This anticoagulant property makes aspirin useful for reducing the incidence of heart attacks.<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4456 |title=Aspirin in Heart Attack and Stroke Prevention |accessdate=2008-05-08 |publisher=American Heart Association }}</ref> 40 mg of aspirin a day is able to inhibit a large proportion of maximum thromboxane A<sub>2</sub> release provoked acutely, with the prostaglandin I2 synthesis being little affected; however, higher doses of aspirin are required to attain further inhibition.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Tohgi| first = H| coauthors = S Konno, K Tamura, B Kimura and K Kawano | year = 1992 | title = Effects of low-to-high doses of aspirin on platelet aggregability and metabolites of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin | journal = Stroke| volume = Vol 23 | pages = 1400–1403 |pmid=1412574}}</ref> |

|||

Prostaglandins are local [[hormone]]s produced in the body and have diverse effects in the body, including the transmission of pain information to the brain, modulation of the [[hypothalamus|hypothalamic]] thermostat, and inflammation. Thromboxanes are responsible for the aggregation of [[platelet]]s that form [[clot|blood clots]]. Heart attacks are primarily caused by blood clots, and low doses of aspirin are seen as an effective medical intervention for acute [[myocardial infarction]]. The major side-effect of this is that because the ability of blood to clot is reduced, excessive bleeding may result from the use of aspirin. |

|||

There are at least two different types of cyclooxygenase: COX-1 and COX-2. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COX-1 and modifies the enzymatic activity of COX-2. Normally COX-2 produces prostanoids, most of which are pro-inflammatory. Aspirin-modified COX-2 produces lipoxins, most of which are anti-inflammatory. Newer NSAID drugs called [[COX-2 selective inhibitor]]s have been developed that inhibit only COX-2, with the intent to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side-effects.<ref name="cox3article" /> |

|||

However, several of the new [[COX-2 selective inhibitor]]s, such as [[Vioxx]], have been recently withdrawn, after evidence emerged that COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of heart attack. It is proposed that endothelial cells lining the microvasculature in the body express COX-2, and, by selectively inhibiting COX-2, prostaglandins (specifically PGI2; prostacyclin) are downregulated with respect to thromboxane levels, as COX-1 in platelets is unaffected. Thus, the protective anti-coagulative effect of PGI2 is decreased, increasing the risk of thrombus and associated heart attacks and other circulatory problems. Since platelets have no DNA, they are unable to synthesize new COX once aspirin has irreversibly inhibited the enzyme, an important difference with reversible inhibitors. |

|||

Furthermore, aspirin has been shown to have at least three additional modes of action. It uncouples [[oxidative phosphorylation]] in cartilaginous (and hepatic) mitochondria, by diffusing from the inner membrane space as a proton carrier back into the mitochondrial matrix, where it ionizes once again to release protons.<ref name="SomasundaramS">{{cite journal|last=Somasundaram, S. et al.|year=2000|title=Uncoupling of intestinal mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and inhibition of cyclooxygenase are required for the development of NSAID-enteropathy in the rat|journal=Aliment Pharmacol Ther|volume=14|pages=639–650|url=http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00723.x|accessdate=2008-05-28|doi=10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00723.x|doi_brokendate=2008-06-24}}</ref> In short, aspirin buffers and transports the protons. When high doses of aspirin are given, aspirin may actually cause fever due to the heat released from the electron transport chain, as opposed to the antipyretic action of aspirin seen with lower doses. Additionally, aspirin induces the formation of NO-radicals in the body, which have been shown in mice to have an independent mechanism of reducing inflammation. This reduced leukocyte adhesion, which is an important step in immune response to infection; however, there is currently insufficient evidence to show that aspirin helps to fight infection.<ref> Mark J. Paul-Clark, Thong van Cao, Niloufar Moradi-Bidhendi, Dianne Cooper, and Derek W. Gilroy 15-epi-lipoxin A4–mediated Induction of Nitric Oxide Explains How Aspirin Inhibits Acute Inflammation |

|||

J. Exp. Med. 200: 69-78; published online before print as 10.1084/jem.20040566</ref> More recent data also suggests that salicylic acid and its derivatives modulate signaling through [[NF-κB]].<ref>{{cite journal | last = McCarty| first = MF| coauthors = KI Block | year = 2006 | title = Preadministration of high-dose salicylates, suppressors of NF-kappaB activation, may increase the chemosensitivity of many cancers: an example of proapoptotic signal modulation therapy | journal = Integr Cancer Ther.| volume = Vol 5 |issue = 3 | pages = 252–268 | pmid= 16880431 |doi=10.1177/1534735406291499}}</ref> NF-κB is a [[transcription factor]] complex that plays a central role in many biological processes, including inflammation. |

|||

==Chemistry== |

|||

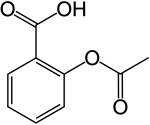

Aspirin is an [[acetyl]] derivative of salicylic acid that is a white, crystalline, weakly acidic substance, with [[melting point]] 135°C. Acetylsalicylic acid decomposes rapidly in solutions of [[ammonium acetate]] or of the [[acetates]], [[carbonates]], [[citrates]] or [[hydroxides]] of the [[alkali metals]]. Acetylsalicylic acid is stable in dry air, but gradually [[hydrolyses]] in contact with moisture to acetic and salicylic [[acids]]. In solution with alkalis, the hydrolysis proceeds rapidly and the clear solutions formed may consist entirely of acetate and salicylate.<ref> |

|||

Reynolds EF (ed) (1982). Aspirin and similar analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. Martindale, The Extra Pharmacopoeia 28 Ed, 234-82.</ref> |

|||

=== Synthesis === |

|||

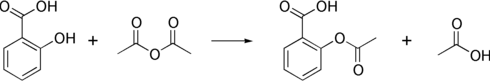

The synthesis of aspirin is classified as an [[esterification]] reaction, where the alcohol group from the [[salicylic acid]] reacts with an acid derivative ([[acetic anhydride]]), yielding aspirin and [[acetic acid]] as a byproduct. Small amounts of [[sulfuric acid]] (and occasionally [[phosphoric acid]]) are used as a catalyst. This method is commonly employed in undergraduate teaching labs.<ref>{{cite book |title=Experimental Organic Chemistry |last=Palleros |first=Daniel R. |year=2000 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons|location=New York|isbn=0-471-28250-2 |pages=494}}</ref> |

|||

:[[Image:Aspirin synthesis.png|490px]] |

|||

Formulations containing high concentrations of aspirin often smell like [[vinegar]].<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.newton.dep.anl.gov/askasci/chem00/chem00314.htm |title=Aspirin Aging |accessdate=2008-05-08 |last=Barrans |first=Richard |publisher=Newton BBS }}</ref> This is because aspirin can decompose in moist conditions, yielding salicylic acid and [[ethanoic acid]].<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Carstensen |

|||

| first = J.T. |

|||

| coauthors = F Attarchi and XP Hou |

|||

| title = Decomposition of aspirin in the solid state in the presence of limited amounts of moisture |

|||

| journal = Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences |

|||

| volume = 77 |

|||

| issue = 4 |

|||

| pages = 318–21 |

|||

| month = Jul | year = 1985 |pmid=4032246 |

|||

| doi = 10.1002/jps.2600770407 }}</ref> |

|||

The acid dissociation constant ([[Acid dissociation constant|pK<sub>a</sub>]]) for acetylsalicylic acid is 3.5 at 25 °C.<ref name="asaaciddissconst">{{cite web | title = Acetylsalicylic acid | publisher = Jinno Laboratory, School of Materials Science, Toyohashi University of Technology | date = [[March 1]] [[1996]] | url = http://chrom.tutms.tut.ac.jp/JINNO/DRUGDATA/07acetylsalicylic_acid.html | accessdate = 2007-09-07}}</ref> |

|||

===Polymorphism=== |

|||

[[Polymorphism (materials science)|Polymorphism]], or the ability of a substance to form more than one [[crystal structure]], is important in the development of pharmaceutical ingredients. Many drugs are receiving regulatory approval for only a single crystal form or polymorph. For a long time, only one crystal structure for aspirin was known, although there had been indications that aspirin might have a second crystalline form since the 1960s. The elusive second polymorph was first discovered by Vishweshwar and coworkers in 2005,<ref>{{cite journal | author= Peddy Vishweshwar, Jennifer A. McMahon, Mark Oliveira, Matthew L. Peterson, and Michael J. Zaworotko| title = The Predictably Elusive Form II of Aspirin | journal = [[J. Am. Chem. Soc.]] | year = 2005 | volume = 127 | issue = 48 | pages = 16802–16803 | doi = 10.1021/ja056455b}}</ref> and fine structural details were given by Bond et al.<ref>{{cite journal | author= Andrew D. Bond, Roland Boese, Gautam R. Desiraju | title = On the Polymorphism of Aspirin: Crystalline Aspirin as Intergrowths of Two "Polymorphic" Domains | journal = [[Angewandte Chemie International Edition]] | year = 2007 | volume = 46 | issue = 4 | pages = 618–622 | doi = 10.1002/anie.200603373}}</ref> A new crystal type was found after attempted co-crystallization of aspirin and [[levetiracetam]] from hot [[acetonitrile]]. The form II is only stable at 100 [[Kelvin|K]] and reverts back to form I at ambient temperature. In the (unambiguous) form I, two salicylic molecules form centrosymmetric [[dimer]]s through the [[acetyl]] groups with the (acidic) [[methyl]] proton to [[carbonyl]] [[hydrogen bond]]s, and in the newly claimed form II, each salicylic molecule forms the same hydrogen bonds with two neighboring molecules instead of one. With respect to the hydrogen bonds formed by the [[carboxylic acid]] groups both polymorphs form identical dimer structures. |

|||

==Pharmacokinetics== |

|||

[[Salicylic acid]] is a weak acid, and very little of it is ionized in the [[stomach]] after oral administration. Acetylsalicylic acid is poorly soluble in the [[pH|acidic]] conditions of the stomach, which can delay absorption of high doses for 8 to 24 hours. In addition to the increased pH of the [[small intestine]], aspirin is rapidly absorbed there due to the increased surface area, which in turn allows more of the salicylate to dissolve. Due to the issue of solubility, however, aspirin is absorbed much more slowly during overdose, and [[blood plasma|plasma]] concentrations can continue to rise for up to 24 hours after ingestion.<ref name='RK Ferguson'> {{cite journal|title=Death following self-poisoning with aspirin|journal=Journal of the American Medical Association|date=1970-08-17|first=RK|last=Ferguson|coauthors=Boutros, AR|volume=|issue=|pages=|pmid=5468267 }}</ref><ref name='FL Kaufman'> {{cite journal|title=Darvon poisoning with delayed salicylism: a case report|journal=Pediatrics|date=1970-04|first=FL|last=Kaufman|coauthors=Dubansky, AS|volume=49|issue=4|pages=610–1|pmid=5013423 }}</ref><ref name='G Levy'> {{cite journal|title=Salicylate accumulation kinetics in man|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|date=1972-09-31|first=G|last=Levy|coauthors=Tsuchiya, T|volume=287|issue=9|pages=430–2|pmid=5044917 |url= }}</ref> |

|||

About 50–80% of salicylate in the blood is bound by [[protein]] while the rest remains in the active, ionized state; protein binding is concentration-dependent. Saturation of binding sites leads to more free salicylate and increased toxicity. The volume of distribution is 0.1–0.2 l/kg. Acidosis increases the volume of distribution because of enhancement of tissue penetration of salicylates.<ref name='G Levy'/> |

|||

As much as 80% of therapeutic doses of salicylic acid is [[metabolism|metabolized]] in the [[liver]]. Conjugation with [[glycine]] forms [[salicyluric acid]] and with [[glucuronic acid]] forms salicyl acyl and phenolic glucuronide. These metabolic pathways have only a limited capacity. Small amounts of salicylic acid are also hydroxylated to gentisic acid. With large salicylate doses, the kinetics switch from first order to zero order, as [[metabolic pathway]]s become saturated and [[kidneys|renal]] excretion becomes increasingly important.<ref name="G Levy"/> |

|||

Salicylates are excreted mainly by the [[kidneys]] as salicyluric acid (75%), free salicylic acid (10%), salicylic phenol (10%) and acyl (5%) glucuronides, and gentisic acid (< 1%). When small doses (less than 250 mg in an adult) are ingested, all pathways proceed by first order kinetics, with an elimination half-life of about 2 to 4.5 hours.<ref name='O Hartwig'>{{cite journal|title=Pharmacokinetic considerations of common analgesics and antipyretics|journal=American Journal of Medicine|date=1983-11-14|first=Otto H|last=Hartwig|coauthors=|volume=75|issue=5A|pages=30–7|pmid=6606362 |pmc=1725844 |doi=10.1016/0002-9343(83)90230-9}}</ref><ref name='AK Done'> {{cite journal|title=Salicylate intoxication. Significance of measurements of salicylate in blood in cases of acute ingestion|journal=Pediatrics|date=1960-11|first=AK|last=Done|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=800–7|pmid=13723722 |url= }}</ref> When higher doses of salicylate are ingested (more than 4 g), the half-life becomes much longer (15-30 hours)<ref name="Chyka2007"/> because the biotransformation pathways concerned with the formation of salicyluric acid and salicyl phenolic glucuronide become saturated.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Prescott LF, Balali-Mood M, Critchley JA, Johnstone AF, Proudfoot AT |title=Diuresis or urinary alkalinisation for salicylate poisoning? |journal=Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) |volume=285 |issue=6352 |pages=1383–6 |year=1982 |month=November |pmid=6291695 |pmc=1500395 |doi= }}</ref> Renal excretion of salicylic acid becomes increasingly important as the metabolic pathways become saturated, because it is extremely sensitive to changes in [[urine|urinary]] pH. There is a 10 to 20 fold increase in renal clearance when urine pH is increased from 5 to 8. The use of urinary alkalinization exploits this particular aspect of salicylate elimination.<ref name="EmergMed2002-Dargan"/> |

|||

==Contraindications and resistance== |

|||

<!--Note that Contraindications is spelled correctly! It does not need to be changed.--> |

|||

Aspirin should be avoided by those known to be allergic to [[ibuprofen]] or [[naproxen]],<ref name="drugs.com"/><ref name="personalmd" /> or to have [[salicylate intolerance]]<ref name="pmid16247191">{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Raithel M, Baenkler HW, Naegel A, ''et al'' |

|||

| title = Significance of salicylate intolerance in diseases of the lower gastrointestinal tract |

|||

| journal = J. Physiol. Pharmacol. |

|||

| volume = 56 Suppl 5 |

|||

| issue = |

|||

| pages = 89–102 |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| month = September |

|||

| pmid = 16247191 |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| url = http://www.jpp.krakow.pl/journal/archive/0905_s5/pdf/89_0905_s5_article.pdf |

|||

| issn = |

|||

|format=PDF}}</ref><ref name="pmid8566739">{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Senna GE, Andri G, Dama AR, Mezzelani P, Andri L |

|||

| title = Tolerability of imidazole salycilate in aspirin-sensitive patients |

|||

| journal = Allergy Proc |

|||

| volume = 16 |

|||

| issue = 5 |

|||

| pages = 251–4 |

|||

| year = 1995 |

|||

| pmid = 8566739 |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| url = http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=1088-5412&volume=16&issue=5&spage=251&aulast=Senna |

|||

| issn = |

|||

}}</ref> or a more generalized [[drug intolerance]] to NSAIDs, and caution should be exercised in those with [[asthma]] or [[NSAID]]-precipitated [[bronchospasm]]. Due to its effect on the stomach lining, manufacturers recommend that patients with [[kidney disease]], [[peptic ulcer]]s, mild [[diabetes]], [[gout]] or [[gastritis]] talk to their doctors before using aspirin.<ref name="drugs.com"/><ref name="mercksource">{{Citation| title = PDR® Guide to Over the Counter (OTC) Drugs|url=http://www.mercksource.com/pp/us/cns/cns_hl_pdr.jspzQzpgzEzzSzppdocszSzuszSzcnszSzcontentzSzpdrotczSzotc_fullzSzdrugszSzfgotc036zPzhtm| accessdate = 2008-04-28 }}.</ref> Even if none of these conditions are present, there is still an increased risk of [[gastrointestinal hemorrhage|stomach bleeding]] when aspirin is taken with [[alcoholic beverage|alcohol]] or [[warfarin]].<ref name="drugs.com"/><ref name="personalmd" /> Patients with [[hemophilia]] or other bleeding tendencies should not take aspirin or other salicylates.<ref name="drugs.com"/><ref name="mercksource" /> Aspirin is known to cause [[hemolytic anemia]] in people who have the genetic disease [[glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency]] (G6PD), particularly in large doses and depending on the severity of the disease.<ref>{{Citation| title = G6PD (Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) Deficiency|url=http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/uvahealth/adult_blood/glucose.cfm |accessdate = 2008-05-07|publisher=University of Virginia}}</ref><ref>{{Citation| title = G6PD (Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) Deficiency|url=http://www.utmbhealthcare.org/Health/Content.asp?PageID=P00091 |accessdate = 2008-05-07 |publisher=University of Texas Medical Branch}}</ref> Aspirin should not be given to children or adolescents to control cold or influenza symptoms as this has been linked with [[Reye's syndrome]].<ref name="BMJ2002-Macdonald"/> Use of aspirin during [[Dengue Fever]] is not recommended due to increased bleeding tendency.<ref>{{Citation |title= Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: Information for Health Care Practitioners|url = http://www.cdc.gov/NCIDOD/dvbid/dengue/dengue-hcp.htm| accessdate = 2008-04-28}}</ref> |

|||

For some people, aspirin does not have as strong an effect on platelets as for others, an effect known as [[aspirin resistance]] or insensitivity. One study has suggested that women are more likely to be resistant than men<ref>{{cite news | title=Aspirin may be less effective heart treatment for women than men | date=2007-04-26. | publisher= | url =http://www.ns.umich.edu/htdocs/releases/story.php?id=5825 | work =University of Michigan | pages = | accessdate = 2007-09-09 | language = }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Dorsch MP, Lee JS, Lynch DR, Dunn SP, Rodgers JE, Schwartz T, Colby E, Montague D, Smyth SS |title=Aspirin Resistance in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease with and without a History of Myocardial Infarction |journal=Ann Pharmacother |volume= 41|issue=May |pages= 737|year=2007 |month=24 Apr |pmid=17456544 |doi=10.1345/aph.1H621}}</ref> and a different, aggregate study of 2,930 patients found 28% to be resistant.<ref>{{cite news| title=Increased risk of heart attack or stroke for patients who are resistant to aspirin | date=2008-01-17 | url=http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2008-01/bmj-iro011608.php | accessdate=2008-01-20}}</ref> |

|||

== Adverse effects == |

|||

===Gastrointestinal side effects=== |

|||

Aspirin use has been shown to increase the risk of [[gastrointestinal bleeding]].<ref name="H Toft">{{cite journal |author=Sørensen HT, Mellemkjaer L, Blot WJ, ''et al'' |title=Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with use of low-dose aspirin |journal=Am. J. Gastroenterol. |volume=95 |issue=9 |pages=2218–24 |year=2000 |month=Sept |pmid=11007221 |doi=10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02248.x |url=http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0002-9270&date=2000&volume=95&issue=9&spage=2218}}</ref> Although some enteric coated formulations of aspirin are advertised as being "gentle to the stomach", in one study enteric coating did not seem to reduce this risk.<ref name="H Toft" /> Combining aspirin with other [[NSAID]]s has also been shown to further increase this risk.<ref name="H Toft" /> Using aspirin in combination with [[clopidogrel]] or [[warfarin]] also increases the risk of upper GI bleeding.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM & Suissa S |month=August |year=2007 |title=Drug drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding |journal=CMAJ |volume=177 |issue=4 |pages=347–51 |pmid=17698822 |doi=10.1503/cmaj.070186 |pmc=1942107}}</ref> |

|||

===Central effects=== |

|||

Large doses of salicylate, a metabolite of aspirin, have been proposed to cause [[tinnitus]], based on the experiments in rats, via the action on arachidonic acid and NMDA receptors cascade.<ref name="Gutton">{{cite journal |author=Guitton MJ, Caston J, Ruel J, Johnson RM, Pujol R, Puel JL |title=Salicylate induces tinnitus through activation of cochlear NMDA receptors |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=23 |issue=9 |pages=3944–52 |year=2003 |month=May |pmid=12736364 |doi= |url=http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/full/23/9/3944}}</ref> |

|||

===Pediatrics=== |

|||

{{see also|Reye's syndrome}} |

|||

Reye's syndrome can occur when children or pediatric patients are given aspirin for a fever or other illnesses or infections. In one study, 213 patients under the age of 18 were reported for Reye's syndrome from the nationwide Reye's syndrome surveillance system. Out of 213 patients 211 had known that had another antecedent illness: 89% reported being ill (severe vomiting, mental strain, respiratory illness, vericella or gastrointestinal illness) two weeks before onset of Reye's syndrome. Salicylate levels, the active acid in aspirin, were present in 162 of the 213 patients. <ref>{{cite journal |author=Rogers MF, Schonberger LB, Hurwitz ES & Rowley DL |month=February |year=1985 |title=National Reye syndrome surveillance, 1982 |journal=Pediatrics |volume=75 |issue=2 |pages=260–4 |pmid=3969325}}</ref> |

|||

Reye's syndrome is due to fatty deterioration of liver cells. In another study, 12 livers were obtained from children who had died from Reye's syndrome, and another liver from a child who died of accidental causes was used as a control. The autopsy stated in seven of the 12 livers, micro vesicular fatty change was present.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rogan WJ, Yang GC & Kimbrough RD |month=March |year=1985 |title=Aflatoxin and Reye’s syndrome: a study of livers from deceased cases |journal=ArchEnviron Health |volume=40 |issue=2 |pages=91–5 |pmid=4004347}}</ref> |

|||

===Other effects=== |

|||

Aspirin can cause prolonged bleeding after operations for up to 10 days. In one study, thirty patients were observed after their various surgeries. Twenty of the thirty patients had to have an additional unplanned operation because of postoperative bleeding.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Scher, K.S. |month=January |year=1996 |title=Unplanned reoperation for bleeding |journal=Am Surg |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=52–55 |pmid=8540646}}</ref> This diffuse bleeding was associated with aspirin alone or in combination with another NSAID in 19 out of the 20 who had to have another operation due to bleeding after their operation. The average recovery time for the second operation was 11 days. |

|||

Aspirin can induce [[angioedema]] in some people. In one study, angioedema appeared 1-6 hours after ingesting aspirin in some of the patients participating in the study. However, when the aspirin was taken alone it did not cause angioedema in these patients; the aspirin was either taken in combination with another NSAID-induced drug when angioedema appeared.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Berges-Gimeno MP & Stevenson DD |month=June |year=2004 |title=Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced reactions and desensitization |journal=J Asthma |volume=41 |issue=4 |pages=375–84 |pmid=15281324 |doi=10.1081/JAS-120037650}}</ref> |

|||

== Interactions == |

|||

Aspirin is known to [[Drug interaction|interact]] with other drugs. For example, [[acetazolamide]] and [[ammonium chloride]] have been known to enhance the intoxicating effect of salicyclates, and [[alcohol]] also enhances the gastrointestinal bleeding associated with these types of drugs as well.<ref name='drugs.com'> {{cite web|url=http://www.drugs.com/aspirin.html |title=Aspirin information from Drugs.com |accessdate=2008-05-08 |publisher=Drugs.com }}</ref><ref name='personalmd'> {{cite web|url=http://www.personalmd.com/drgdb/3.htm |title=Oral Aspirin information |accessdate=2008-05-08 |publisher=First DataBank }}</ref> Aspirin is known to displace a number of drugs from protein binding sites in the blood, including the [[anti-diabetic drug]]s [[tolbutamide]] and [[chlorpropamide]], the [[immunosuppressant]] [[methotrexate]], [[phenytoin]], [[probenecid]], [[valproic acid]] (as well as interfering with [[beta oxidation]], an important part of valproate metabolism) and any [[NSAID|nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug]]. Corticosteroids may also reduce the concentration of aspirin. The pharmacological activity of [[spironolactone]] may be reduced by taking aspirin, and aspirin is known to compete with [[Penicillin|Penicillin G]] for renal tubular secretion.<ref name="interactions">Katzung (1998), p. 584.</ref> Aspirin may also inhibit the absorption of [[vitamin C]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Loh HS, Watters K & Wilson CW |year=1973 |title=The Effects of Aspirin on the Metabolic Availability of Ascorbic Acid in Human Beings |journal=J Clin Pharmacol |volume=13 |issue=11 |pages=480–6 |pmid=4490672 |url=http://jcp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/13/11/480}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Basu TK |month= |year=1982 |title=Vitamin C-aspirin interactions |journal=Int J Vitam Nutr Res Suppl |volume=23 |issue= |pages=83–90 |pmid=6811490}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Ioannides C, Stone AN, Breacker PJ & Basu TK |month=December |year=1982 |title=Impairment of absorption of ascorbic acid following ingestion of aspirin in guinea pigs |journal=Biochem Pharmacol |volume=31 |issue=24 |pages=4035–8 |pmid=6818974 |doi=10.1016/0006-2952(82)90652-9}}</ref> |

|||

== Dosage == |

|||

[[Image:Regular strength enteric coated aspirin tablets.jpg|thumb|Coated 325 mg aspirin tablets]] |

|||

For adults doses are generally taken four times a day for fever or arthritis,<ref name=BNF>{{cite book | title=[[British National Formulary]] | edition=45 | month=March | year=2003 | publisher= [[British Medical Journal]] and [[Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain]]}}</ref> with doses near the maximal daily dose used historically for the treatment of rheumatic fever.<ref>[http://www.medscape.com/druginfo/monograph?cid=med&drugid=3881&drugname=Aspirin+EC+Oral&monotype=monograph Aspirin monograph: dosages, etc]</ref> For the prevention of myocardial infarction in someone with documented or suspected coronary artery disease, much lower doses are taken once daily.<ref name=BNF /> |

|||

For those under 12 years of age, the dose previously varied with the age, but aspirin is no longer routinely used in children due to the association with [[Reye's syndrome]]; [[paracetamol]] (known as acetaminophen in North America) or other NSAIDs, such as [[ibuprofen]], are now used instead. [[Kawasaki disease]] remains one of the few indications for aspirin use in children, with aspirin taken at dosages based on body weight, initially four times a day for up to two weeks and then at a lower dose once daily for a further six to eight weeks.<ref>{{cite book | title=[[British National Formulary for Children]] | year=2006 | publisher= [[British Medical Journal]] and [[Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain]]}}</ref> |

|||

== Overdose == |

|||

{{Splitsection|salicylate intoxication|date=August 2008}} |

|||

Aspirin overdose can be acute or chronic. In acute poisoning, a single large dose is taken; in chronic poisoning, supratherapeutic doses are taken over a period of time. Acute overdose has a [[mortality rate]] of 2%. Chronic overdose is more commonly lethal with a mortality rate of 25%; chronic overdose may be especially severe in children.<ref name="Pediatrics1982-gaudreault">{{cite journal | author=Gaudreault P, Temple AR, Lovejoy FH Jr. | title=The relative severity of acute versus chronic salicylate poisoning in children: a clinical comparison | journal=Pediatrics | year=1982 | pages=566–9 | volume=70 | issue=4 | pmid= 7122154}}</ref> |

|||

=== Symptoms === |

|||

Aspirin overdose has potentially serious consequences, sometimes leading to significant [[morbidity]] and [[death]]. Patients with mild [[intoxication]] frequently have [[nausea]] and [[vomiting]], abdominal pain, lethargy, [[tinnitus]], and [[dizziness]]. More significant symptoms occur in more severe poisonings and include [[hyperthermia]], [[tachypnea]], [[respiratory alkalosis]], [[metabolic acidosis]], [[hyperkalemia]], [[hypoglycemia]], [[hallucinations]], [[Mental confusion|confusion]], [[seizure]], [[cerebral edema]], and [[coma]]. The most common cause of death following an aspirin overdose is cardiopulmonary arrest usually due to [[pulmonary edema]].<ref name="ActaAnaesthesiol1987-Thisted">{{cite journal | author=Thisted B, Krantz T, Stroom J, Sorensen MB. | title=Acute salicylate self-poisoning in 177 consecutive patients treated in ICU | journal=Acta Anaesthesiol Scand | year=1987 | pages=312–6 | volume=31 | issue=4 | pmid= 3591255}}</ref> |

|||

=== Toxicity === |

|||

The acutely [[toxic]] dose of aspirin is generally considered greater than 150 mg per kg of body mass.<ref name="Chyka2007">{{cite journal |author=Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Christianson G, Wax PM, Booze LL, Manoguerra AS, Caravati EM, Nelson LS, Olson KR, Cobaugh DJ, Scharman EJ, Woolf AD, Troutman WG; Americal Association of Poison Control Centers; Healthcare Systems Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. |title=Salicylate poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management |journal=Clin Toxicol (Phila) |volume=45 |issue=2 |pages=95–131 |year=2007 |pmid=17364628 |doi=10.1080/15563650600907140 |url=}}</ref> Moderate toxicity occurs at doses up to 300 mg/kg, severe toxicity occurs between 300 to 500 mg/kg, and a potentially lethal dose is greater than 500 mg/kg.<ref name="ArchInternMed1981-Temple">{{cite journal | author=Temple AR. | title=Acute and chronic effects of aspirin toxicity and their treatment | journal=Arch Intern Med | year=1981 | pages=364–9 | volume=141 | issue=3 Spec No | pmid= 7469627 | doi=10.1001/archinte.141.3.364}}</ref> This is the equivalent of many dozens of the common 325 mg tablets, depending on body weight. Chronic toxicity may occur following doses of 100 mg/kg per day for two or more days.<ref name="ArchInternMed1981-Temple"/> |

|||

=== Treatment === |

|||

All overdose patients should be conveyed to a hospital for assessment immediately. Initial treatment of an acute overdose includes gastric decontamination. This is achieved by administering [[activated charcoal]], which [[adsorbs]] the aspirin in the [[gastrointestinal tract]]. [[gastric lavage|Stomach pumps]] are no longer routinely used in the treatment of poisonings but are sometimes considered if the patient has ingested a potentially lethal amount less than 1 hour previously.<ref name=”jtoxclintox2004-vale”>{{cite journal | author=Vale JA, Kulig K; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. | title=Position paper: gastric lavage | journal=J Toxicol Clin Toxicol | year=2004 | pages=933–43 | volume=42 | issue=7 | pmid= 15641639 | doi=10.1081/CLT-200045006}}</ref> Inducing [[emesis]] with [[syrup of ipecac]] is not recommended.<ref name="Chyka2007"/> Repeated doses of charcoal have been proposed to be beneficial in aspirin overdose;<ref name="BMJ1985-hillman">{{cite journal | author=Hillman RJ, Prescott LF. | title=Treatment of salicylate poisoning with repeated oral charcoal | journal=Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) | year=1985 | pages=1472 | volume=291 | issue=6507 | pmid= 3933714}}</ref> although, one study found that repeat dose charcoal might not be of significant value.<ref name="ArchInternMed1990-Kirshenbaum">{{cite journal | author=Kirshenbaum LA, Mathews SC, Sitar DS, Tenenbein M. | title=Does multiple-dose charcoal therapy enhance salicylate excretion? | journal=Arch Intern Med | year=1990 | pages=1281–3 | volume=150 | issue=6 | pmid= 2191636 |id= | doi=10.1001/archinte.150.6.1281}}</ref> However, most clinical toxicologists will administer additional charcoal if serum salicylate levels are increasing. |

|||

Patients are monitored until their peak salicylate blood level has been determined.<ref name="EmergMed2002-Dargan">{{cite journal | author=Dargan PI, Wallace CI, Jones AL. | title=An evidenced based flowchart to guide the management of acute salicylate (aspirin) overdose | journal=Emerg Med J | year=2002 | pages=206–9 | volume=19 | issue=3 | pmid= 11971828 |doi=10.1136/emj.19.3.206|pmc=1725844}}</ref> Blood levels are usually assessed four hours after ingestion and then every two hours after that to determine the maximum level. Maximum levels can be used as a guide to toxic effects expected.<ref name="drugs1986-Meredith">{{cite journal | author=Meredith TJ, Vale JA. | title=Non-narcotic analgesics. Problems of overdosage | journal=Drugs | year=1986 | pages=117–205 | volume=32 | issue=Suppl 4 | pmid= 3552583 | doi=10.2165/00003495-198600324-00013}}</ref> |

|||

There is no antidote to salicylate poisoning. Monitoring of biochemical parameters such as electrolytes, liver and kidney function, [[urinalysis]], and [[complete blood count]] is undertaken along with frequent checking of [[salicylate]] and [[blood sugar]] levels. [[Arterial blood gas]] assessments are performed to test for [[alkalosis|respiratory alkalosis]] and [[metabolic acidosis]]. Patients are monitored and often treated according to their individual symptoms, patients may be given [[intravenous]] [[potassium chloride]] to counteract [[hypokalemia]], [[glucose]] to restore [[blood sugar]] levels, [[benzodiazepines]] for any seizure activity, fluids for [[dehydration]], and importantly [[sodium bicarbonate]] to restore the blood's sensitive [[pH]] balance. Sodium bicarbonate also has the effect of increasing the pH of urine, which in turn increases the elimination of salicylate. Additionally, [[hemodialysis]] can be implemented to enhance the removal of salicylate from the blood. Hemodialysis is usually used in severely poisoned patients; for example, patients with significantly high salicylate blood levels, significant neurotoxicity (agitation, coma, convulsions), renal failure, pulmonary edema, or cardiovascular instability are hemodialyzed.<ref name="EmergMed2002-Dargan"/> Hemodialysis also has the advantage of restoring [[electrolyte]] and [[acid-base]] abnormalities while removing salicylate;<ref name="EmergMed2002-Dargan"/> hemodialysis is often life-saving in severely ill patients. |

|||

=== Epidemiology === |

|||

In the later part of the 20th century the number of salicylate poisonings has declined mainly due to the popularity of other over-the-counter analgesics such as [[paracetamol]] (acetaminophen). Fifty-two deaths involving single-ingredient aspirin were reported in the [[United States]] in 2000. However, in all but three cases, the reason for the ingestion of lethal doses was intentional, predominantly suicides.<ref name="AmJEmergMed2001-Litovitz">{{cite journal | author=Litovitz TL, Klein-Schwartz W, White S, Cobaugh DJ, Youniss J, Omslaer JC, Drab A, Benson BE | title=2000 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System | journal=Am J Emerg Med | year=2001 | pages=337–95 | volume=19 | issue=5 | pmid= 11555795 |doi=10.1053/ajem.2001.25272 }}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{portal|Pharmacy and Pharmacology|Tabletten.JPG}} |

|||

*[[Aspergum]] |

|||

*[[Copper aspirinate]] |

|||

*[[Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug]] |

|||

*[[History of aspirin]] |

|||

*[[Salicylic acid]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{commons|Aspirin}} |

|||

* {{imdb title|id=1182937|title=Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi}} |

|||

*[http://redpoll.pharmacy.ualberta.ca/drugbank/cgi-bin/getCard.cgi?CARD=APRD00264 DrugBank Aspirin Entry] |

|||

* [http://www.indiafm.com/movies/cast/13824/index.html ''Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi'' on Indiafm.com] |

|||

*[http://www.nextbio.com/b/home/home.nb?q=aspirin NextBio Aspirin Entry] |

|||

*[http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/321/7276/1591 Reappraisal] |

|||

*[http://almaz.com/nobel/medicine/aspirin.html An aspirin a day keeps the doctor away] |

|||

*[http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/en/bia/gallery.html?image=24 Colour-enhanced scanning electron micrograph of aspirin crystals] |

|||

* [http://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/1biochem/research7.html Aspirin research in the 1990s] |

|||

*[http://www.med.mcgill.ca/mjm/issues/v02n02/aspirin.html The History of Aspirin] |

|||

*[http://www.jhu.edu/~jhumag/0297web/health.html Aspirin and heart disease] |

|||

*[http://www.howstuffworks.com/aspirin How Aspirin works] |

|||

*[http://www.bluerhinos.co.uk/molview/indv.php?id=5 Molview from bluerhinos.co.uk] See Aspirin in 3D |

|||

*[http://biotechnology-innovation.com.au/innovations/pharmaceuticals/aspro.html History of Aspro] |

|||

*[http://www.creatingtechnology.org/biomed/aspirin.htm The science behind aspirin] |

|||

* [http://pubs.acs.org/subscribe/journals/mdd/v03/i08/html/10health.html Take two: Aspirin], New uses and new dangers are still being discovered as aspirin enters its second century. Shauna Roberts, American Chemical Society |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia | last = Ling | first = Greg | title = Aspirin | encyclopedia = How Products are Made | volume = 1 | pages = | publisher = Thomson Gale | location = | year = 2005 | isbn = | url = http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Aspirin.html}} |

|||

*[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE5258 A Gene Expression Omnibus entry of a genome-wide transcriptional expression data for bioactive small molecules (Aspirin among them)] |

|||

<br> |

|||

{{Antithrombotics}} |

|||

{{Anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products}} |

|||

{{NSAIDs}} |

|||

{{analgesics}} |

|||

[[Category:Aspirin|*]] |

|||

[[Category:Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs]] |

|||

[[Category:Antiplatelet drugs]] |

|||

[[Category:Acetates]] |

|||

[[Category:Benzoic acids]] |

|||

[[Category:Bayer brands]] |

|||

[[Category:Equine medications]] |

|||

{{ |

{{Link FA|he}} |

||

{{Link FA|nl}} |

|||

[[ar:أسبرين]] |

|||

[[Category:Upcoming films]] |

|||

[[ |

[[ast:Aspirina]] |

||

[[bn:অ্যাসপিরিন]] |

|||

[[Category:Indian films]] |

|||

[[bs:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[Category:Hindi-language films]] |

|||

[[bg:Ацетилсалицилова киселина]] |

|||

[[pl:Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi]] |

|||

[[ca:Aspirina]] |

|||

[[cs:Kyselina acetylsalicylová]] |

|||

[[da:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[de:Acetylsalicylsäure]] |

|||

[[et:Aspiriin]] |

|||

[[el:Ασπιρίνη]] |

|||

[[es:Ácido acetilsalicílico]] |

|||

[[eo:Aspirino]] |

|||

[[fa:استیل سالیسیلیک اسید]] |

|||

[[fr:Acide acétylsalicylique]] |

|||

[[gl:Aspirina]] |

|||

[[ko:아스피린]] |

|||

[[hr:Acetilsalicilna kiselina]] |

|||

[[id:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[is:Acetýlsalicýlsýra]] |

|||

[[it:Acido acetilsalicilico]] |

|||

[[he:אספירין]] |

|||

[[ht:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[ku:Aspîrîn]] |

|||

[[lt:Aspirinas]] |

|||

[[hu:Acetilszalicilsav]] |

|||

[[ms:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[nl:Acetylsalicylzuur]] |

|||

[[ja:アスピリン]] |

|||

[[no:Acetylsalisylsyre]] |

|||

[[nn:Acetylsalisylsyre]] |

|||

[[ps:اسپرين]] |

|||

[[pl:Kwas acetylosalicylowy]] |

|||

[[pt:Aspirina]] |

|||

[[ro:Aspirină]] |

|||

[[ru:Ацетилсалициловая кислота]] |

|||

[[simple:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[sk:Kyselina acetylsalicylová]] |

|||

[[sl:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[sr:Аспирин]] |

|||

[[fi:Asetyylisalisyylihappo]] |

|||

[[sv:Acetylsalicylsyra]] |

|||

[[ta:ஆஸ்பிரின்]] |

|||

[[th:แอสไพริน]] |

|||

[[vi:Aspirin]] |

|||

[[tr:Asetil salisilik asit]] |

|||

[[uk:Ацетилсаліцилова кислота]] |

|||

[[wa:Aspirene]] |

|||

[[zh:阿司匹林]] |

|||

Revision as of 13:08, 12 October 2008

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 2-acetyloxybenzoic acid 2-(acetyloxy)benzoic acid acetylsalicylate acetylsalicylic acid O-acetylsalicylic acid |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Most commonly oral, also rectal. Lysine acetylsalicylate may be given IV or IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Rapidly and completely absorbed |

| Protein binding | 99.6% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 300–650 mg dose: 3.1–3.2hrs 1 g dose: 5 hours 2 g dose: 9 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.059 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H8O4 |

| Molar mass | 180.160 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.40 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 135 °C (275 °F) |

| Boiling point | 140 °C (284 °F) (decomposes) |

| Solubility in water | 10 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

Aspirin, or acetylsalicylic acid (A.S.A.) (/əˌsɛtɨlsælɨˌsɪlɨk ˈæsɨd/), is a salicylate drug, often used as an analgesic to relieve minor aches and pains, as an antipyretic to reduce fever, and as an anti-inflammatory medication.

In countries where Aspirin is a registered trademark owned by Bayer, the generic term is "A.S.A."

Aspirin also has an antiplatelet or "anti-clotting" effect and is used in long-term, low doses to prevent heart attacks, strokes and blood clot formation in people at high risk for developing blood clots.[1] It has also been established that low doses of aspirin may be given immediately after a heart attack to reduce the risk of another heart attack or of the death of cardiac tissue.[2][3]

The main undesirable side effects of aspirin are gastrointestinal—ulcers and stomach bleeding—and tinnitus, especially in higher doses. In children under 19 years of age, aspirin is no longer used to control flu-like symptoms or the symptoms of chickenpox, due to the risk of Reye's syndrome.[4]

Aspirin was the first-discovered member of the class of drugs known as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), not all of which are salicylates, although they all have similar effects and most have some mechanism of action which involves non-selective inhibition of the enzyme cyclooxygenase. Today, aspirin is one of the most widely used medications in the world, with an estimated 40,000 metric tons of it being consumed each year.[5]

History

Medicines containing derivatives of salicylic acid, structurally similar to aspirin, have been in medical use since ancient times. Salicylate-rich willow bark extract became recognized for its specific effects on fever, pain and inflammation in the mid-eighteenth century. By the nineteenth century pharmacists were experimenting with and prescribing a variety of chemicals related to salicylic acid, the active component of willow extract.

A French chemist, Charles Frederic Gerhardt, was the first to prepare acetylsalicylic acid (named aspirin in 1899) in 1853. In the course of his work on the synthesis and properties of various acid anhydrides, he mixed acetyl chloride with a sodium salt of salicylic acid (sodium salicylate). A vigorous reaction ensued, and the resulting melt soon solidified.[6] Since no structural theory existed at that time, Gerhardt called the compound he obtained "salicylic-acetic anhydride" (wasserfreie Salicylsäure-Essigsäure). This preparation of aspirin ("salicylic-acetic anhydride") was one of the many reactions Gerhardt conducted for his paper on anhydrides, and he did not pursue it further.

Six years later, in 1859, von Gilm obtained analytically pure acetylsalicylic acid (which he called "acetylierte Salicylsäure", acetylated salicylic acid) by a reaction of salicylic acid and acetyl chloride.[7] In 1869 Schröder, Prinzhorn and Kraut repeated both Gerhardt's (from sodium salicylate) and von Gilm's (from salicylic acid) syntheses and concluded that both reactions gave the same compound—acetylsalicylic acid. They were first to assign to it the correct structure with the acetyl group connected to the phenolic oxygen.[8]

In 1897, scientists at the drug and dye firm Bayer began investigating acetylsalicylic acid as a less-irritating replacement for standard common salicylate medicines. By 1899, Bayer had dubbed this drug Aspirin and was selling it around the world.[9]The name Aspirin is derived from A = Acetyl and "Spirsäure" = an old (German) name for salicylic acid.[10] Aspirin's popularity grew over the first half of the twentieth century, spurred by its effectiveness in the wake of Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, and aspirin's profitability led to fierce competition and the proliferation of aspirin brands and products, especially after the American patent held by Bayer expired in 1917.[11][12]

As part of war reparations following Germany's surrender after World War I, Aspirin lost its status as a registered trademark in France, United Kingdom and the United States where it became a generic name.[13] Aspirin remains a registered trademark of Bayer in Germany and in over 80 other countries.[14]

Aspirin's popularity declined after the market releases of paracetamol (acetaminophen) in 1956 and ibuprofen in 1969.[15] In the 1960s and 1970s, John Vane and others discovered the basic mechanism of aspirin's effects, while clinical trials and other studies from the 1960s to the 1980s established aspirin's efficacy as an anti-clotting agent that reduces the risk of clotting diseases.[16] Aspirin sales revived considerably in the last decades of the twentieth century, and remain strong in the twenty-first, thanks to widespread use as a preventive treatment for heart attacks and strokes.[17]

Therapeutic uses

Aspirin is one of the most frequently used drugs in the treatment of mild to moderate pain, including that of migraines and fever.[18][19] It is often combined with other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioid analgesics in the treatment of moderate to severe pain.[20]

In high doses, aspirin and other salicylates are used in the treatment of rheumatic fever, rheumatic arthritis, and other inflammatory joint conditions. In lower doses, aspirin also has properties as an inhibitor of platelet aggregation, and has been shown to decrease the incidence of transient ischemic attacks and unstable angina in men, and can be used prophylactically. It is also used in the treatment of pericarditis, coronary artery disease, and acute myocardial infarction.[21][22] Low doses of aspirin are also recommended for the prevention of stroke, and myocardial infarction in patients with either diagnosed coronary artery disease or who have an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease.

Experimental uses

Aspirin has been theorized to reduce cataract formation in diabetic patients, but one study showed it was ineffective for this purpose.[23] The role of aspirin in reducing the incidence of many forms of cancer has also been widely studied. In several studies, aspirin use did not reduce the incidence of prostate cancer.[24][25] Its effects on the incidence of pancreatic cancer are mixed; one study published in 2004 found a statistically significant increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer among women,[26] while a meta-analysis of several studies, published in 2006, found no evidence that aspirin or other NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk for the disease.[27] The drug may be effective in reduction of risk of various cancers, including those of the colon,[28][29][30][31] lung,[32][33] and possibly the upper GI tract, though some evidence of its effectiveness in preventing cancer of the upper GI tract has been inconclusive.[34][35][34] Its preventative effect against adenocarcinomas may be explained by its inhibition of COX-2 enzymes expressed in them.[36] An older study[citation needed] claimed that aspirin may reduce the neurotoxicity of THC, the active drug in cannabis. However, this theory has been discredited, as newer studies[citation needed] indicate THC to be neuroprotective rather than neurotoxic.

Veterinary uses

Aspirin has been used to treat pain and arthritis in veterinary medicine, primarily in cats and dogs, although it is often not recommended for this purpose, as there are newer medications available with fewer side effects in these animals. Dogs, for example, are particularly susceptible to the gastrointestinal side effects associated with salicylates.[37] Horses have also been given aspirin for pain relief, although it is not commonly used due to its relatively short-lived analgesic effects. Horses are also fairly sensitive to the gastrointestinal side effects. Nevertheless, it has shown promise in its use as an anticoagulant, mostly in cases of laminitis.[38] Aspirin should only be used in animals under the direct supervision of a veterinarian.

Mechanism of action

In 1971, British pharmacologist John Robert Vane, then employed by the Royal College of Surgeons in London, showed that aspirin suppressed the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes.[39][40] For this discovery, he was awarded both a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1982 and a knighthood.

Aspirin's ability to suppress the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes is due to its irreversible inactivation of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme. Cyclooxygenase is required for prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis. Aspirin acts as an acetylating agent where an acetyl group is covalently attached to a serine residue in the active site of the COX enzyme. This makes aspirin different from other NSAIDs (such as diclofenac and ibuprofen), which are reversible inhibitors.

Low-dose, long-term aspirin use irreversibly blocks the formation of thromboxane A2 in platelets, producing an inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation. This anticoagulant property makes aspirin useful for reducing the incidence of heart attacks.[41] 40 mg of aspirin a day is able to inhibit a large proportion of maximum thromboxane A2 release provoked acutely, with the prostaglandin I2 synthesis being little affected; however, higher doses of aspirin are required to attain further inhibition.[42]

Prostaglandins are local hormones produced in the body and have diverse effects in the body, including the transmission of pain information to the brain, modulation of the hypothalamic thermostat, and inflammation. Thromboxanes are responsible for the aggregation of platelets that form blood clots. Heart attacks are primarily caused by blood clots, and low doses of aspirin are seen as an effective medical intervention for acute myocardial infarction. The major side-effect of this is that because the ability of blood to clot is reduced, excessive bleeding may result from the use of aspirin.

There are at least two different types of cyclooxygenase: COX-1 and COX-2. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COX-1 and modifies the enzymatic activity of COX-2. Normally COX-2 produces prostanoids, most of which are pro-inflammatory. Aspirin-modified COX-2 produces lipoxins, most of which are anti-inflammatory. Newer NSAID drugs called COX-2 selective inhibitors have been developed that inhibit only COX-2, with the intent to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side-effects.[5]

However, several of the new COX-2 selective inhibitors, such as Vioxx, have been recently withdrawn, after evidence emerged that COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of heart attack. It is proposed that endothelial cells lining the microvasculature in the body express COX-2, and, by selectively inhibiting COX-2, prostaglandins (specifically PGI2; prostacyclin) are downregulated with respect to thromboxane levels, as COX-1 in platelets is unaffected. Thus, the protective anti-coagulative effect of PGI2 is decreased, increasing the risk of thrombus and associated heart attacks and other circulatory problems. Since platelets have no DNA, they are unable to synthesize new COX once aspirin has irreversibly inhibited the enzyme, an important difference with reversible inhibitors.