Star Wars (film)

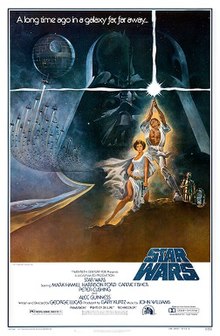

| Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | George Lucas |

| Written by | George Lucas |

| Produced by | Gary Kurtz George Lucas (executive) |

| Starring | Mark Hamill Harrison Ford Carrie Fisher Peter Cushing Alec Guinness |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Taylor |

| Edited by | Richard Chew Paul Hirsch Marcia Lucas |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates | May 25, 1977 (USA) December 27, 1977 (UK) |

Running time | 121 min. (original) 125 min. (Special Edition) |

| Country | USA |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11,000,000 |

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, originally released as Star Wars, is a 1977 science fantasy film written and directed by George Lucas. It is the first of six films released in the Star Wars saga; three later films precede the story in the series' internal chronology. Among fans, the title is commonly abbreviated as "ANH".[1]

The film is set 19 years after the formation of the Galactic Empire; construction has finished on the Death Star, a weapon capable of destroying a planet. After Princess Leia, a leader of the Rebel Alliance, receives the weapon's plans in the hope of finding a weakness, she is captured and taken to the Death Star. Meanwhile, a young farmer named Luke Skywalker meets Obi-Wan Kenobi, who has lived in seclusion for years on the desert planet of Tatooine. When Luke's home is destroyed, Obi-Wan begins Luke’s Jedi training as they attempt to rescue the Princess from the Empire.

Inspired by films like the Flash Gordon serials and such literary works as The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Lucas began work on Star Wars in 1974. Produced with a budget of US$11 million and released on May 25, 1977, the film became one of the most successful of all time, earning $215 million in the United States and $337 million overseas during its original theatrical release, as well as winning several film awards, including 10 Academy Award nominations. It was re-released several times, sometimes with significant changes; the most notable versions were the 1997 Special Edition and the 2004 DVD, which were modified with CGI effects and recreated scenes.

asdflakslhfk

Releases

Charles Lippincott was hired by Lucas' production company, Lucasfilm Ltd., as marketing director for Star Wars. Because 20th Century Fox gave little support for marketing beyond licensing T-shirts and posters, Lippincott was forced to look elsewhere. He secured deals with Stan Lee, Roy Thomas and Marvel Comics for a comic book adaptation and with Del Rey Books for a novelization. Wary that Star Wars would be beaten out by other summer films, such as Smokey and the Bandit, 20th Century Fox moved the release date to Wednesday before Memorial Day: May 25, 1977. However, few theaters ordered the film to be shown. In response, 20th Century Fox demanded that theaters order Star Wars if they wanted an eagerly anticipated film based on a best-selling novel titled The Other Side of Midnight.[2]

The film became an instant success; within three weeks of the film's release, 20th Century Fox's stock price doubled to a record high. Before 1977, 20th Century Fox's greatest annual profits were $37,000,000; in 1977, the company earned $79,000,000. Although the film's cultural neutrality helped it to gain international success, Ladd became anxious during the premiere in Japan. After the screening, the audience was silent, leading Ladd, Jr. to fear that the film would be unsuccessful. He was later told that, in Japan, silence was the greatest honor to a film. Meanwhile, thousands attended a ceremony at Grauman's Chinese Theatre, where C-3PO, R2-D2 and Darth Vader placed their footprints in the theater's forecourt.[2] Although Star Wars merchandise was available to enthusiastic children upon release, only Kenner Toys — who believed that the film would be unsuccessful — had accepted Lippincott's licensing offers. Kenner responded to the sudden demand for toys by selling boxed vouchers in its "empty box" Christmas campaign; these vouchers could be redeemed for the toys in March 1978.[2]

In 1978, at the height of the film's popularity, Smith-Hemion Productions approached Lucas with the idea of The Star Wars Holiday Special. The end result is often considered a failure; Lucas himself disowned it.[3]

The film was originally released as — and consequently often called — Star Wars, without Episode IV or the subtitle A New Hope. The 1980 sequel, Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back, featured the episode number and subtitle in the opening crawl. When the original film was re-released in 1981, Episode IV: A New Hope was added above the original opening crawl. Although Lucas claims that only six films were ever planned, representatives of Lucasfilm discussed plans for nine or 12 possible films in early interviews.[4] The film was re-released theatrically in 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982, and 1997.

Special Edition

After ILM used computer generated effects for Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park, Lucas concluded that digital technology had caught up to his original vision for Star Wars.[2] As part of Star Wars' 20th anniversary celebration in 1997, A New Hope was digitally remastered and re-released with The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi under the campaign title The Star Wars Trilogy: Special Edition, or SE. The Special Edition versions contained visual shots and scenes that were unachievable in the original release due to financial, technological, and time restraints; one such scene involved a meeting between Han Solo and Jabba the Hutt.[2] Although most changes were minor or cosmetic in nature, some fans believe that Lucas degraded the movie with the additions.[5] For instance, a controversial change in which Greedo shoots first when confronting Han Solo has inspired T-shirts brandishing the phrase "Han Shot First".[6]

DVD release

A New Hope was released on DVD on September 21, 2004 in a box set with The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, and a bonus disc of supplemental material. The movies were digitally restored and remastered, and more changes were made by George Lucas.

The DVD features a commentary track from George Lucas, Ben Burtt, Dennis Muren, and Carrie Fisher. The bonus disc contains the documentary Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy, three featurettes, teaser and theatrical trailers, TV spots, still galleries, an exclusive preview of Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, a playable Xbox demo of the LucasArts game Star Wars Battlefront, and a "Making Of" documentary on the Episode III video game. The set was reissued in December 2005 as part of a three-disc "limited edition" boxed set without the bonus disc.

The trilogy was re-released on separate two-disc Limited Edition DVD sets from September 12, 2006 to December 31, 2006; the original versions of the films were added as bonus material. Controversy surrounded the release because the unaltered versions were from the 1993 non-anamorphic Laserdisc masters, and were not retransferred with modern video standards.[7]

Reaction

Star Wars debuted on May 25 1977 in 32 theaters, and proceeded to break house records, effectively becoming one of the first blockbuster films.[8] It remains one of the most financially successful films of all time. Some of the cast and crew noted lines of people stretching around theaters as they drove by. Even minor technical crew members, such as model makers, were asked for autographs, and cast members became instant household names.[2] The film's original total U.S. gross came to $307,263,857, and it earned $6,806,951 during its first weekend in wide release. Lucas claimed that he had spent most of the release day in a sound studio in Los Angeles. When he went out for lunch with his then-wife Marcia, they encountered a long queue of people along the sidewalks leading to Mann's Chinese Theatre, waiting to see Star Wars.[9] The film became the highest-grossing film of 1977 and the highest-grossing film of all time until E.T. The Extraterrestrial broke that record in 1982. (With subsequent rereleases, Star Wars reclaimed the title, but lost it again to James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster Titanic.) The film earned $797,900,000 worldwide, making it the first film to reach the $300 million mark.[10] Adjusted for inflation it is the second highest grossing movie of all time in the United States, behind Gone with the Wind.[11]

In a 1977 review, Roger Ebert called the film "an out-of-body experience", compared its special effects to those of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and opined that the true strength of the film was its "pure narrative".[12] Vincent Canby called the film "the movie that's going to entertain a lot of contemporary folk who have a soft spot for the virtually ritualized manners of comic-book adventure."[13] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker criticized the film, stating that "there's no breather in the picture, no lyricism", and that it had no "emotional grip".[14] Jonathon Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader stated, "None of these characters has any depth, and they're all treated like the fanciful props and settings!"[15] Peter Keough of the Boston Phoenix said "Star Wars is a junkyard of cinematic gimcracks not unlike the Jawas' heap of purloined, discarded, barely functioning droids."[16] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic also responded negatively, noting, "His work here seems less inventive than in THX 1138."[17] According to rottentomatoes.com, of the 54 critical reviews of the film provided on that site, 51 responded favorably, stating in consensus that "the action and special effects are first rate."[17]

In 1989, the U.S. National Film Registry of the Library of Congress selected the film as a "culturally, historically, or aesthetically important" film.[18] In 2006, Lucas' original screenplay was selected by the Writers Guild of America as the 68th greatest of all time.[19] The American Film Institute (or AFI) listed it 15th on a list of the top 100 films of the 20th century;[20] in the UK, a poll created by Channel Four named A New Hope (together with its successor, The Empire Strikes Back) the greatest film of all time.[21] The American Film Institute has named Star Wars and specific elements of it to several of its "top 100 lists" of American cinema, compiled as a part of the Institute's 100th anniversary celebration. These include the 27th most thrilling American film of all time;[22] the thirty-ninth most inspirational American film of all-time;[23] Han Solo as the fourteenth greatest American film hero of all time and Obi-Wan Kenobi thirty-seventh on the same list. Darth Vader was chosen as the third greatest film villain. [24] The often repeated line "May the Force be with you" was ranked as the 8th greatest quote in American film history.[25] John Williams' score was ranked as the greatest American film score of all time.[26]

Star Wars won several awards at the 1978 Academy Awards, including Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, which went to John Barry, Norman Reynolds, Leslie Dilley and Roger Christian. Best Costume Design was awarded to John Mollo; Best Film Editing went to Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew; John Stears, John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, Grant McCune and Robert Blalack all received awards for Best Effects, Visual Effects. John Williams was awarded his third Oscar for Best Music, Original Score; the Best Sound went to Don MacDougall, Ray West, Bob Minkler and Derek Ball; and a Special Achievement for sound effects went to Ben Burtt. Additional nominations included Alec Guinness for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, George Lucas for Best Screenplay and Best Director, and Gary Kurtz was nominated for his producing duties in Best Picture.[27] At the Golden Globe awards, the film was nominated for Best Motion Picture - Drama, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (Alec Guinness), and Best Score. It only won the award for Best Score.[27] It received six BAFTA nominations: Best Film, Best Editing, Best Costume, Best Production/Art Design, Best Sound, and Best Score; the film won in the latter two categories.[27] John Williams' soundtrack album won the Grammy award for Best Album of an original score for a motion picture or television program,[27] and the film was awarded the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[27] In 1997, the MTV Movie Awards awarded Chewbacca the lifetime achievement award for his work in the Star Wars trilogy.[27]

Cinematic influence

Star Wars has influenced many films and filmmakers since its release.[28] It began a new generation of special effects and high-energy motion pictures. The film was one of the first films to link genres — such as space opera and soap opera — together to invent a new, high-concept genre for filmmakers to build upon.[28][29] Finally, it shifted the film industry's focus away from personal filmmaking of the 1970s and towards big-budget blockbusters for younger audiences.[28][2]

Actor Michael Shanks cited Star Wars as an influence on many battle scenes from the television series Stargate SG-1 namely "Fallen".[30] Joss Whedon's Serenity features several references: the spaceship Serenity, influenced by the Millennium Falcon; a "used future" where vehicles and culture are obviously dated; and clothing for its own evil empire.[31] After seeing Star Wars, director James Cameron quit his job as a truck driver to enter the film industry. Other filmmakers who have said to have been influenced by Star Wars include Peter Jackson, Ridley Scott, Dean Devlin, Roland Emmerich, and John Singleton..[29] Scott, like Whedon, was influenced by the "used future" and extended the concept for his science fiction horror film Alien. Jackson used the concept for his production of the Lord of the Rings trilogy to add a sense of realism and believability.[29]

Critics of Lucas have blamed Star Wars for "ruining" Hollywood by shifting its focus from "sophisticated" and "relevant" films such as The Godfather, Taxi Driver, and Annie Hall to films about "spectacle" and "juvenile fantasy".[32] Peter Biskind complained for the same reason: "When all was said and done, Lucas and Spielberg returned the 1970s audience, grown sophisticated on a diet of European and New Hollywood films, to the simplicities of the pre-1960s Golden Age of movies… They marched backward through the looking-glass."[33][32]

Cast

- Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker. Skywalker is a young man who lives with his aunt and uncle on a remote planet and who dreams of something greater than his current position in life.

- Harrison Ford as Han Solo. Solo is a self-centered smuggler whom Obi-Wan and Luke meet in a cantina and later travel with. Solo, who owns the ship Millennium Falcon, is good friends with Chewbacca, the ship's co-pilot.

- Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia Organa. Organa is a member of the Imperial Senate and a leader of the Rebel Alliance. She plans to use the stolen Death Star plans to find the station's weakness.

- Alec Guinness as "Ben" Obi-Wan Kenobi. Kenobi is an aging man who served as a Jedi Master during the Clone Wars. Early in the film, Kenobi introduces Luke to the Force.

- David Prowse as Darth Vader. Vader is a Dark Lord of the Sith, and a prominent figure in the Galactic Empire who hopes to destroy the Rebel Alliance. He was Obi-Wan's apprentice before turning to the dark side of the Force. James Earl Jones provided the voice.

- Anthony Daniels as C-3PO. C-3PO is an interpreter droid who falls into the hands of Luke Skywalker. He is never without his counterpart droid, R2-D2.

- Kenny Baker as R2-D2. R2-D2 is a mechanic droid who also falls into the hands of Luke. He is carrying a secret message for Obi-Wan Kenobi.

- Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca. Chewbacca is the Wookiee co-pilot of the Millennium Falcon and a close friend of Han Solo.

- Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin. Tarkin is the commander of the Death Star. He leads the search for the Rebel Base, hoping to destroy it.

- Denis Lawson as Wedge Antilles. Wedge is a starfighter pilot who fights with Luke in the Battle of Yavin. In the ending credits, Lawson's first name is misspelled "Dennis".

Lucas shared a joint casting session with long-time friend Brian De Palma, who was casting his own film Carrie. As a result, Carrie Fisher and Sissy Spacek auditioned for both films in each other's respective roles.[34] Lucas favored casting young actors without long-time experience. While reading for Luke Skywalker (then known as "Luke Starkiller"), Hamill found the dialogue to be extremely odd because of its universe-embedded concepts. He chose to simply read it sincerely and was selected instead of William Katt, who was subsequently cast in Carrie.[2][35][36] Lucas initially rejected the idea of using Harrison Ford, as he had previously worked with him on American Graffiti, and instead asked Ford to assist in the auditions by reading lines with the other actors and explaining the concepts and history behind the scenes that they were reading. Lucas was eventually won over by Ford's portrayal and cast him instead of Kurt Russell, Burt Reynolds, Nick Nolte,[36] Christopher Walken, Billy Dee Williams and Perry King.[34][37][2] Virtually every young actress in Hollywood auditioned for the role of Princess Leia, including Terri Nunn,[38] Jodie Foster[34] and Cindy Williams.[2] Carrie Fisher was cast under the condition that she lose 10 pounds of weight for the role. Aware that the studio disagreed with his refusal to cast big-name stars, Lucas signed veteran stage and screen actor Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi.[2]

Additional casting took place in London, England, where Mayhew was cast as Chewbacca after he stood up to greet Lucas. Lucas immediately turned to Gary Kurtz, and requested that Mayhew be cast.[39] Daniels auditioned for and was cast as C-3PO after he saw a McQuarrie drawing of the character; struck by the vulnerability in the robot's face, he instantly wanted to help to bring the character to life.[2][40]

Cinematic and literary allusions

According to Lucas, the film was inspired by numerous sources, such as Beowulf and King Arthur for the origins of myth and world religions.[2] Lucas originally wanted to rely heavily on 1930s Flash Gordon film serials; however, Lucas resorted to Akira Kurosawa's film The Hidden Fortress and Joseph Campbell's The Hero With a Thousand Faces because of copyright issues with Flash Gordon.[41][42] The scene in which Princess Leia awards Han and Luke is similar to a scene in Leni Riefenstahl's 1934 film Triumph of the Will; both scenes have large, enthusiastic crowds seated in a shallow amphitheater bounded by columns, with a low dais where the leader stands.[43]

Star Wars features several parallels to Flash Gordon, such as the conflict between Rebels and Imperial Forces, the "wipes" between scenes, and the famous "opening crawl" that begins each film. A concept borrowed from Flash Gordon — a fusion of futuristic technology and traditional magic — was originally developed by one of the founders of science fiction, H.G. Wells. Wells believed the Industrial Revolution had quietly destroyed the idea that fairy-tale magic might be real. Thus, he found that plausibility was required to allow myth to work properly, and substituted elements of the Industrial Era: time machines instead of magic carpets, Martians instead of dragons, and scientists instead of wizards. Wells called his new genre "scientific fantasia".[44][45][46]

Star Wars was influenced by the 1958 Kurosawa film The Hidden Fortress; for instance, the two bickering peasants evolved into C-3PO and R2-D2, and a Japanese family crest seen in the film is similar to the Imperial Crest. Star Wars borrows heavily from another Kurosawa film, Yojimbo. In both films, several men threaten the hero, bragging how wanted they are by authorities. The situation ends with an arm being cut off by a blade. Mifune is offered "twenty-five ryo now, twenty-five when you complete the mission." whereas Han Solo is offered "Two thousand now, plus fifteen when we reach Alderaan." Lucas' affection for Kurosawa may have influenced his decision to visit Japan in the early 1970s, where he borrowed the name "Jedi" from jidaigeki (which in English means "period dramas", and refers to films typically featuring samurai).[47][46][48]

Lucas also drew inspiration from J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy book The Lord of the Rings. Obi-Wan Kenobi is similar to the Wizard Gandalf, albeit in differing fashions, and Darth Vader resembles the Witch-king of Angmar in that both are the chief servants of a higher evil power and dress in black. Luke watches the duel of Obi-Wan and Vader from across a chasm as Frodo witnessed the duel between Gandalf and the Balrog; both feature their respective blue and red mêlée weapons. There are numerous other similarities between the two works[49]

Tatooine is similar to Arrakis from Frank Herbert's book Dune. Arrakis is the only known source of a longevity drug called the Spice Melange; Han Solo is a spice smuggler who has been through the spice mines of Kessel. Lucas' original concept of the film dealt heavily with the transport of spice, although the nature of the material remained unexplored. In the conversation at Obi-Wan Kenobi's home between Obi-Wan and Luke, Luke expresses a belief that his father was a navigator on a spice freighter. Other similarities include those between Princess Leia and Princess Alia (pronounced [ə.ˈliː.ə]), and between Jedi mind tricks and "The Voice", a controlling ability used by Bene Gesserit. In passing, Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru are "Moisture Farmers"; in Dune, Dew Collectors are used by Fremen to "provide a small but reliable source of water".[50][51]

There are subtle parallels to the Japanese serial Space Cruiser Yamato (Star Blazers); both Wildstar and Skywalker are young and hot-headed but grow into mature leaders; Captain Avatar and Obi-Wan each portray the wizened old warrior; the similarities between R2-D2 and IQ-9 are unmistakable. Additionally, in both stories the heroes fly fighter plane-type spacecraft; the Death Star and the Comet Empire perform similar functions and the chief villains (Darth Vader and Desslok) meet similar fates.

The Death Star assault scene was modeled after the 1950s movie The Dam Busters, in which Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers fly along heavily defended reservoirs and aim "bouncing bombs" at their man-made dams to cripple the heavy industry of the Ruhr. Some of the dialogue in The Dam Busters is repeated in the A New Hope climax; Gilbert Taylor also filmed the special effects sequences in The Dam Busters.[52][48] In addition, the sequence was partially inspired by the climax of the film 633 Squadron directed by Walter Grauman.[53]

The opening shot of Star Wars, in which a detailed spaceship fills the screen overhead, is a nod to the scene introducing the interplanetary spacecraft Discovery One in Stanley Kubrick's seminal 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. The earlier big-budget science fiction film influenced the look of A New Hope in many other ways, including the use of EVA pods, hexagonal corridors, and primitive computer graphics. The orbiting space station in 2001 has a docking bay reminiscent of the one on the Death Star.[54] The film also draws on The Wizard of Oz: similarities exist between Jawas and Munchkins, the main characters disguise themselves as enemy soldiers, and Obi-Wan dies, leaving only his empty robe in the same fashion as the Wicked Witch of the West.[55][56] Although golden and male, C-3PO is inspired by the robot Maria from Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis. His whirring sounds were speculated to be inspired by the clanking noises of the Tin Woodsman in The Wizard of Oz.[57][58]

Soundtrack

On the recommendation of his friend Steven Spielberg, Lucas hired composer John Williams, who had worked with Spielberg on the film Jaws, for which he won an Academy Award. Lucas felt that the film would portray visually foreign worlds, but that the musical score would give the audience an emotional familiarity. In March 1977, Williams conducted the London Symphony Orchestra to record the Star Wars soundtrack in twelve days.[2]

Lucas wanted a grand musical sound for Star Wars, with leitmotifs to provide distinction. Therefore, he assembled his favorite orchestral pieces for the soundtrack, until John Williams convinced him that an original score would be unique and more unified. However, a few of Williams pieces were influenced by the tracks given to him by Lucas. The "Main Title Theme" was inspired by the theme from the 1942 film King's Row, scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and the track "Dune Sea of Tatooine" drew from the soundtrack from Bicycle Thieves, scored by Alessandro Cicognini.[41]

Novelization

The novelization of the film was published in December 1976, six months before the film was released. The credited author was George Lucas, but the book was revealed to have been ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster, who later wrote the first Expanded Universe novel, Splinter of the Mind's Eye. The book was first published as Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker; later editions were titled simply Star Wars and, later, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, to reflect the retitling of the film. Certain scenes deleted from the film (and later restored or archived in DVD bonus features) were present in the novel, such as Luke at Tosche Station with Biggs and the encounter between Han and Jabba in Docking Bay 94. Other deleted scenes from the movie, such as a close-up of a stormtrooper riding on a Dewback, were included in a photo insert added to later printings of the book.

Smaller details were also changed; for example, in the Death Star assault, Luke's callsign is Blue Five instead of Red Five as in the film. Charles Lippincott secured the deal with Del Rey Books to publish the novelization in November 1976. By February 1977, a half million copies had been sold.[2]

Radio drama

A radio drama adaptation of the film was written by Brian Daley, directed by John Madden, and produced for and broadcast on the American National Public Radio network in 1981. The adaptation received cooperation from George Lucas, who donated the rights to NPR. John Williams' music and Ben Burtt's sound design were retained for the show; Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker) and Anthony Daniels (C-3PO) reprised their roles, as well. The radio drama featured deleted scenes of Luke Skywalker's observation of the space battle above Tatooine through binoculars, a skyhopper race, and Darth Vader's interrogation of Princess Leia. In terms of Star Wars canon, the radio drama is given the highest designation, G-canon.[59]

References

- ^ "Star Wars and Star Trek Sources and Abbreviations". Stardestroyer.net. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy Star Wars Trilogy Box Set DVD documentary, [2005]

- ^ "Star Wars on TV". TV Party. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ Time - March 6, 1978; "George Lucas' Galactic Empire - Get ready for Star Wars II, III, IV, V ..."

- ^ "Star Wars: The Changes". dvdactive. Retrieved August 14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Exclusive T-shirts to Commemorate DVD Release". Starwars.com. Retrieved August 14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Ian Dawe. "Anamorphic Star Wars and Other Musings". Mindjack Film. Retrieved 2006-05-26.

- ^ Michael Coate (2004-09-21). "May 25, 1977: A Day Long Remembered". The Screening Room. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Heritagewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Box office data on Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ^ Roger Ebert (January 1, 1977). "Star Wars". Roger Ebert.com. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ Vincent Canby (May 26, 1977). "'Star Wars'—A Trip to a Far Galaxy That's Fun and Funny..." The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ Pauline Kael (September 26, 1977). "Star Wars". New Yorker. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ^ Jonathon Rosenbaum (1997). "Excessive Use of the Force". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ^ Peter Keough (1997). "Star Wars remerchandises its own myth". Boston Phoenix. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ^ a b "Star Wars". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ^ "U.S. National Film Registry Titles". U.S. National Film Registry. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays: The List". Writer's Guild of America. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "100 Greatest Films". Channel 4. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes & Villains". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Film Scores". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ a b c d e f "Awards for Star Wars (1977)". IMDB. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ a b c Roger Ebert (June 28, 1999). "Great Movies: Star Wars". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ^ a b c The Force Is With Them: The Legacy of Star Wars Star Wars Original Trilogy DVD Box Set: Bonus Materials, [2004]

- ^ Stargate SG-1 Season 7: Fallen DVD audio commentary, [2003]

- ^ Tyler, Joshua (2005-09-29). "Movie Review". cinemablend.com. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ^ a b Steven D. Greydanus. "An American Mythology: Why Star Wars Still Matters". Decent Films Guide. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ^ Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'N' Roll Generation Saved Hollywood by Peter Biskind; Simon & Schuster, [April 4, 1999]

- ^ a b c "Alternate Casting". BlueHarvest.net. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ "William Katt". Filmbug. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ a b "The Force Wasn't With Them". Premiere Magazine. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Is it true about Burt Reynolds and Han Solo?". About.com. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Star Wars: A Look Back". Hollywood North Report. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Peter Mayhew Biography". Yahoo!. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Biography: Anthony Daniels". Starwars.com. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ a b "How did George Lucas create Star Wars?". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 15 August.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Campbell, Star Wars and the myth". Muriel Verbeeck. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ "Star Wars and Triumph of the Will". The Unordinary Star Wars Site. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - Flash Gordon". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Wells on The Time Machine". U. Arizona. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ a b "Before A New Hope: THX 1138". Starwars.com. Retrieved 2006-09-03.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - Akira Kurosawa". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ a b "Star Wars". Rotten.com. Retrieved 2006-09-03.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - The Lord of the Rings". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - Frank Herbert's Dune". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Star Wars is Dune". D. A. Houdek. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - Miscellaneous Influences". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Summer 2005 Film Music CD Reviews". Film, Music on the Web. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - 2001 A Space Odyssey". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - The Wizard of Oz". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ^ "Female Hero in Wizard of Oz Compared to Male Hero in Star Wars". Elisa Kay Sparks. Retrieved 2006-09-03.

- ^ "Star Wars Origins - The Droids". Star Wars Origins. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ^ "Star Wars Databank: C-3PO". Starwars.com. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Star Wars, the NPR dramatization". HighBridge Audio. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

Further reading

- Rinzler, J. W. (2007) The Making of Star Wars. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345494764

- Bailey, T.J. (2005) Devising a Dream: A Book of Star Wars Facts And Production Timeline, Wasteland Press. ISBN 1933265558

- Blackman, W. Haden (2004) The New Essential Guide to Weapons and Technology, Revised Edition (Star Wars), Del Rey. ISBN 0345449037

- Pollock, Dale (1999) Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas, Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306809044

- Sansweet, Stephen (1992) Star Wars - From Concept to Screen to Collectible, Chronicle Books. ISBN 0811801012

External links

- Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope at StarWars.com

- Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope at IMDb

- Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope at Rotten Tomatoes

- Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope at Box Office Mojo

- Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope at MovieMistakes.com

- Template:Swwmedia

- Star Wars: The Changes - Part 1

- 1977 films

- American films

- Best Science Fiction Film Saturn

- Coming-of-age films

- English-language films

- Epic films

- Fictional-language films

- Films directed by George Lucas

- Hugo Award Winner for Best Dramatic Presentation

- Lucasfilm films

- Star Wars episodes

- 20th Century Fox films

- United States National Film Registry