ethics

The ethics is that part of the field of philosophy that deals with the conditions and the evaluation of human action and is the methodical thinking about the morality . At the center of ethics is specifically moral action, especially with regard to its justifiability and reflection (ethics describes and judges morality critically). Cicero was the first to translate êthikê into the then new term philosophia moralis . In its tradition, ethics is also referred to as moral philosophy (or philosophy of morals ).

Ethics and its related disciplines (e.g. legal , political and social philosophy ) are also summarized as “ practical philosophy ”, since they deal with human activity . In contrast, there is “ theoretical philosophy ”, which includes logic , epistemology and metaphysics as classical disciplines .

Word origin

The German word ethics comes from the Greek ἠθική (ἐπιστήμη) ēthikē (epistēmē) "the moral (understanding)", from ἦθος ēthos "character, sense" (on the other hand ἔθος: habit, custom, custom). Compare mos in Latin .

origin

Already the Sophists (in the 5th to 4th centuries BC) took the view that it would be inappropriate for a rational being like humans if its actions were guided exclusively by conventions and traditions. As part of the Socratic turn moved Socrates (5th century BC. Chr.) Ethics at the center of philosophical thought. Ethics as a name for a philosophical discipline goes back to Aristotle (4th century BC), who meant the scientific study of habits, manners and customs ( ethos ). He was convinced that human practice was fundamentally amenable to sensible and theoretically sound reflection. Thus, for Aristotle, ethics was a philosophical discipline that deals with the entire area of human activity and subjects this object to a normative assessment using philosophical means and guides the practical implementation of the knowledge gained in this way.

Goals and questions

Today (general) ethics is understood as the philosophical discipline that sets up criteria for good and bad behavior and for the evaluation of its motives and consequences. In terms of its purpose, it is a practical science. It is not about knowing for its own sake (theoria) , but about a responsible practice. It should provide people with help in making moral decisions. However, ethics can only justify general principles and norms of good behavior or ethical judgment in general, or preferential judgments for certain types of problematic situations. The situation-specific application of these principles to new situations and situations in life is not achievable through them, but the task of practical judgment and a trained conscience .

The three questions about

- the "highest good",

- the right action in certain situations and

- the freedom of will

stand in the center.

As a philosophical discipline, ethics is based solely on the principle of reason and logical arguments , while theological ethics presupposes moral principles as founded and revealed in God's will . The "Sollens" statements of the Ten Commandments are known in Judaism . Especially in the 20th century, authors like Alfons Auer tried to conceptualize theological ethics largely autonomously.

Demarcation

Jurisprudence

Legal science also asks how things should be done. In contrast to ethics (which has been distinguished from legal theory since Christian Thomasius and Kant), however, it generally refers to a specific, factually applicable legal system (positive law), the norms of which it interprets and applies. Wherever jurisprudence as legal philosophy , legal policy or legislative doctrine also deals with the justification of legal norms, it approaches ethics. The law of reason also shows parallels to ethics.

Empiricism

Empirical sciences such as sociology, ethnology and psychology also deal with social norms of action. In contrast to normative ethics in the philosophical sense, it is about the description and explanation of factually existing ethical convictions, attitudes and sanction patterns and not about their justification or criticism . There are thus relationships to descriptive ethics.

Rational Decision Theory

The theory of rational decision also answers the question: How should I act? However, it differs from ethical questions in that theories of rational action are not always theories of the morally good. Theories of rational decision-making differ from ethical theories with a generally binding claim in that only the goals and interests of a specific individual or a collective subject (e.g. an economic company or a state) are taken into account.

Disciplines

| discipline | Subject area | method |

|---|---|---|

| Metaethics | Language and logic of moral discourse, methods of moral argumentation, efficiency of ethical theories | analytically |

| Normative ethics | Principles and criteria of morality, standards of morally correct action, principles of a good life for all | abstract judgment |

| Applied ethics | Valid norms, values, recommendations for action in the respective area | concrete judgmental |

| Descriptive ethics | Actually followed preferences for action, empirically available norms and value systems | descriptive |

Metaethics

Metaethics represents the basis of the other disciplines and deals with their generally applicable criteria and methods. It reflects the general logical, semantic and pragmatic structures of moral and ethical speaking. It has been regarded as an independent discipline since the beginning of the 20th century.

Normative ethics

Normative ethics develops and examines generally applicable norms and values as well as their justification. It is the core of general ethics. As a reflection theory of morality, it evaluates and judges what is good and right.

Applied ethics

Applied ethics builds on normative ethics. It expresses itself as individual and social ethics as well as in the area ethics for specific areas of life, for example medical ethics or business ethics . Ethics committees , councils and institutes develop standards or recommendations for action for specific areas.

Descriptive ethics

The descriptive ethics , which does not make moral judgments, but describes the actual morality lived within a society with empirical means, is often not counted in the classical canon of ethics .

Justifications of normative sentences

Reasons for and against morality

The question of whether one should be moral at all is raised in Plato's Politeia in the first chapter. In the modern age, the discourse around the question was initiated by Bradley and Prichard .

Metaethical cognitivists claim to know how to act morally. Thus, the question arises for them whether one should not do that at all, since they also immediately recognize that one should do this.

Metaethical noncognitivists, on the other hand, need to clarify the question of whether one should act morally. The discussion in philosophy is mostly based on the question "Why should one be moral?" The ought within the question is not a moral ought, but refers to an acceptance of better reasons, e.g. B. using the theory of rational decision . So the answer to the question depends on the respective understanding of reason .

The question of whether or not to be moral is answered with:

- "Yes" to all who give reasons for morality,

- "No" from the amoralists ,

- “Everyone has to decide for themselves” by Decisionists .

The situation of the person who has to choose between these answers found its classic form in the so-called Prodikos fable by Heracles at the crossroads , which was also received by many Christian authors.

Absolute justification of morality

A well-known absolute moral justification is that of Apel's ultimate justification . Assuming someone refuses to talk about purposes, then this refusal is already talking about purposes. In this respect, this is a so-called performative self-contradiction .

Justification of morality from the point of view of systems theory refrains from justifying why individuals should act morally. Instead, it explains why morality is indispensable as a regulatory function of the communication system (see also AGIL scheme ).

Relative justifications of morality

Many philosophers claim that while amoralism cannot be proven to be logically inconsistent, in real life amoralists have many disadvantages such that moral behavior has greater profitability in terms of rational choice theory . With this form of moral justification, ethics becomes a special form of functional rationality. One of the most important representatives of this line of argument is David Gauthier .

Many philosophers in this direction invoke the principle of quid pro quo or tit for tat strategies.

Others believe that amoralists are committed to loneliness because they cannot be trusted and neither can they trust anyone. Therefore, they could never achieve one of the most important goods in life, social community and recognition.

According to RM Hare , amoralists cannot use moral terms and therefore cannot ask their fellow human beings to treat them fairly. Hare did not see the possibility of such lies. Hare also claimed that the effort that amoralists had to go to in order to cover up their convictions was so great that they were always socially disadvantaged.

Amoralists criticize various moral justifications by pointing out that in many parts of the world there are relatively stable conditions that contradict the usual moral ideas, e.g. B. illegal wars for resources, slavery or successful Mafia organizations .

Decisionism

Decision (from the Latin decidere: decide, fall, cut off) means something like decision. The term decisionism is often used in a pejorative sense by metaethical cognitivists as opposed to philosophers who only recognize relative grounds of morality, e.g. B. Hare or Popper and Hans Albert .

Decisionists see no alternative to decisions of principle which, for logical or pragmatic reasons, can no longer be justified further. For example, B. Henry Sidgwick , man has to choose between utilitarianism and egoism .

Similar to metaethical noncognitivism, decisionism is countered by its critics by saying that decisions can also be subjected to an evaluation: One does not decide on certain ethical principles, but on the contrary, these would represent the basis of decisions.

In addition, advocates of natural law argue that the objectivity of ethics (i.e. the ought) can be traced back to the nature or essence of beings and ultimately to being itself (e.g. God ).

Basic ethical terms

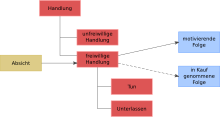

Moral acts

The concept of action is at the center of deontological ethics . As a first approximation, it is defined as “a change in the state of the world caused by a person”. The change can be an external, observable in space and time or an internal, mental change. The way in which external events are encountered can also be referred to in the broader sense as action.

Intention and voluntariness

Actions differ from events in that we do not refer to another event as their cause, but to the agent's intention. The intention ( Latin intentio ; not to be confused with the legal concept of intention, the first degree dolus directus ) is an act that must be distinguished from the act itself. Planned acts are based on an intention that precedes them in time. We carry out the action as we had previously planned. The concept of intention is to be distinguished from that of voluntariness . Voluntariness is a quality that belongs to the act itself. The concept of voluntariness is wider than that of intention; it also includes spontaneous actions, in which one can no longer speak of an intention in the narrower sense.

Knowledge and will

An act is voluntary if it is carried out with knowledge and will.

However, ignorance can only cancel the voluntary nature of an action if the acting person has informed himself beforehand to the best of his ability and if he would have acted differently with the lack of knowledge . If the agent could be expected to know the norm or its consequences, he is responsible for its violation ( ignorantia crassa or supina ). Even less excuses the ignorance that was intentionally brought about to avoid a conflict with the norm (ignorantia affectata) . B. deliberately avoiding informing oneself about a law in order to be able to say that one did not know about a certain prohibition . The saying rightly says: " Ignorance does not protect against punishment ". This fact is also taken into account in German criminal law. So it is called z. B. in § 17 StGB :

“If the perpetrator lacks the insight to do wrong when committing the act, then he acts without guilt if he could not avoid this error. If the perpetrator was able to avoid the mistake, the punishment can be reduced in accordance with Section 49 (1). "

For the moral evaluation of an action, the effective volition is also essential, the intention of its realization. This presupposes that at least the actor was of the opinion that it was possible for him to realize his intention, i.e. That is, that the result can be causally brought about by his actions. If the agent is subject to an external compulsion, this generally removes the voluntary nature of the action.

Principles of action

Intentions are expressed in practical principles. These can first of all be distinguished in terms of content and form. The principles of content are based on specific goods (life, health, property, pleasure, environment, etc.) as evaluation criteria for action. They are partly subjective and may have a decisionist character. In these cases they cannot establish their own primacy over other, competing substantive principles.

Formal principles do not make any reference to specific content. The best-known example is Kant's categorical imperative .

There are basically three levels of practical sentences:

- a supreme principle of practical considerations (such as the categorical imperative )

- practical principles derived from the supreme principle (such as the ten commandments )

- Sentences that formulate decisions by applying maxims to concrete life situations

Ethics is often only able to make statements about the first two levels. The transfer of practical principles to a concrete situation that requires wealth of practical judgment. It is only with his help that any conflicting goals that may arise can be resolved and the likely consequences of decisions assessed.

Consequences of action

The consequences associated with them are essential for the ethical evaluation of actions. These are divided into motivating and accepted consequences. Motivational consequences are those for the sake of which an action is carried out. They are directly targeted by the agent (“Voluntarium in se”).

Consequences accepted (“Voluntarium in causa”) are not directly targeted, but anticipated and consciously allowed as a side effect of the motivating consequences ( principle of double effect ). For example, conscious negligence as a conditional intent (dolus eventualis) is subject to ethical and legal responsibility: Drunkenness does not excuse a traffic accident.

Doing and failing

Thomas Aquinas already distinguishes a twofold causality of the will: the “direct” influence of the will, in which a certain event is caused by the act of will, and the “indirect”, in which an event occurs because the will remains inactive. Doing and failing to do so do not differ in terms of their voluntary nature. If they fail to do so, someone forego intervening in a process, although they would have the opportunity to do so. Failure to do so can therefore also be viewed as an act and be punishable by law.

The strict distinction between these two forms of action, which z. B. plays a major role in medical ethics (cf. active and passive euthanasia etc.), therefore appears to be questionable from an ethical point of view.

The goal of human action

At the center of teleological ethics is the question of what I am ultimately aiming for with my action, what aim I am pursuing with it. The term “goal” (finis, telos;) is to be understood here in particular as “final goal” or “final goal”, which determines all my actions.

Luck as the ultimate goal

In tradition, happiness or bliss (beatitudo) is often mentioned as the ultimate human goal . The term "happiness" is used in an ambiguous sense:

- to denote a successful and good life that lacks nothing essential ("happiness in life", eudaimonia )

- to denote favorable living conditions (" chance luck ", eutychia )

- to denote subjective well-being (happiness as pleasure, hedone )

In the history of philosophy, the determinations of happiness as "happiness in life" and as subjective well-being compete with one another. For the Eudaemonists (Plato, Aristotle) happiness is the result of the realization of a norm which is laid out as telos in the being of man. According to this concept, people who act in a sensible way are especially happy.

For the hedonists (sophists, classical utilitarians) there is no longer any telos of man that can be realized; there is no objective norm available to determine whether someone is happy. This leads to a subjectification of the concept of happiness. It is up to the individual to judge whether they are happy or not. Happiness is sometimes equated with the achievement of goods such as power, wealth, fame, etc.

Purpose and purpose

The word “sense” basically describes the quality of something that makes it understandable. We understand something by recognizing what it is "assigned" to, what it is for. The question of the meaning is therefore closely related to the question of the goal or purpose of something. The meaning of an action or even of life can only be answered if the question of its goal has been clarified. A human act or an entire life is meaningful if it is geared towards this goal.

The good

The term "good"

Like the term “being”, “good” is one of the first and therefore no longer definable terms. A distinction is made between an adjectival and a noun usage.

As an adjective, the word “good” generally describes the assignment of an “object” to a specific function or purpose. So one speaks z. B. from a "good knife" if it fulfills its function expressed in the predictor "knife" - ie z. B. can cut well. Similarly, one speaks of a "good doctor" if he is able to heal his patients and fight diseases. A “good person” is therefore someone who focuses his life on what constitutes being human, that is, corresponds to the human being or his nature.

As a noun, the word “the good” describes something towards which we direct our actions. We normally use it in this way to “judge a choice made under certain conditions as right or justified”. For example, a statement such as “Health is a good” can serve as a justification for choosing a particular way of life and diet. In the philosophical tradition one was of the opinion that in principle every being - with a certain consideration - could be the goal of striving ("omne ens est bonum"). Therefore the “goodness” of beings was counted among the transcendentalities .

According to Richard Mervyn Hare's analysis, judgmental words such as “good” or “bad” are used to guide action or give recommendations in decision-making situations. The words “good” or “bad” therefore do not have a descriptive but a prescriptive function.

This can be illustrated by an extra-moral use of the word “good”. If a seller says to the customer: "This is a good wine", he recommends buying this wine, but is not describing any perceptible property of the wine. Insofar as there are socially widespread evaluation standards for wines (it must not taste like vinegar, you shouldn't get a headache from it, etc.), the evaluation of the wine as "good" means that the wine meets these standards and that it therefore also determines possesses empirical properties.

The evaluation criteria that are applied to a thing can vary depending on the intended use . A bitter wine may be good as a table wine, but rather bad when drunk for yourself. The purpose of a thing is not a fixed property of the thing itself, but is based on human position. One thing is “good” - always based on certain criteria. If the seller says, "This is a very good table wine" then it is what it should be according to the usual table wine criteria.

When the word “good” is used in a moral context (“This was a good deed”), one recommends the deed and expresses that it was as it should be. However, it does not describe the act. If reference is made to generally recognized moral criteria, one also expresses that the act has certain empirical properties, e.g. B. a deferral of self-interest in favor of overriding interests of fellow human beings.

The greatest good

The highest good ( summum bonum ) is that which is not only good under a certain respect (for people), but simply because it corresponds to people as people without restriction. It is identical to what is “absolutely should”. Its content determination depends on the respective point of view of human nature. In the tradition, a wide variety of proposed solutions were presented:

- happiness (eudaemonism)

- lust ( hedonism , classical utilitarianism )

- Power ( Machiavelli )

- Unity with God or God himself ( Christian philosophy )

- Awakening (bodhi) to wisdom and compassion ( Buddhism )

- Satisfaction of needs ( hobbes )

- Unity of virtue and happiness ( Kant )

- Freedom ( sartre )

values

The term “value” originally came from political economy , in which Adam Smith , David Ricardo and later Karl Marx examined, among other things, the distinction between use and exchange value . It was not until the second half of the 19th century that “value” became a philosophical term that assumed a central role in the philosophy of value ( Max Scheler et al.). There it was introduced as a counter-term to the Kantian ethics of duty, on the assumption that values would have an "objective validity" before all reasoning.

In everyday language , the term has recently reappeared more and more, especially when there is talk of “ basic values ”, a “ change in values ” or a “new value debate”.

The concept of value is very similar to the concept of the good . Like this one, it is basically used in a subjective and an objective variant:

- as "objective value" he describes the "value" of certain goods for people - such as B. the value of human life, health, etc. This corresponds to the meaning of “bonum physicum” (“physical good”).

- as “subjective value” he describes what is valuable to me, my “values” - such as loyalty, justice, etc. This corresponds to the meaning of “bonum morale” (“moral good”).

In comparison to the concept of the good, however, the concept of value is more socially conditioned. One speaks of a “change in values” when one wants to express that certain norms of action generally accepted in a society have changed in the course of history. As a rule, however, this does not mean that what was previously considered good is now “actually” no longer good, but only that the general judgment about it has changed.

Virtue

The correct weighing of ethical goods and their implementation presupposes virtue. In its classic definition, Aristotle formulates "that fixed basic attitude from which [the agent] becomes capable and which brings about his peculiar performance in a perfect manner" (NE 1106a).

The achievement of the ethical virtues consists primarily in bringing about a unity of sensual striving and moral knowledge in man. We only designate a person as “good” when he has come to an inner unity with himself and affective fully affirms what has been recognized as correct. According to Aristotle, this is only possible through an integration of feelings through ethical virtues. The disordered feelings distort the moral judgment. The goal of the unity of reason and feeling leads beyond a mere ethics of the right decision. It doesn't just matter what we do, but who we are.

In addition to knowledge, virtue presupposes a habit that is achieved through education and social practice. We become righteous, courageous etc. by putting ourselves in situations where we can behave accordingly. The most important role is played by the virtue of prudence (phronesis). It is up to her to find the right "middle" between the extremes and to decide on the optimal solution for the specific situation.

Should

The term “should” is a basic concept of deontological ethical approaches. It refers - as an imperative - to an action with which a certain goal is to be achieved. The following conditions must be met:

- the given goal can be missed

- the given goal is not in competition with other, overriding goals

- the specified goal can in principle be achieved ("every ought implies a skill")

In terms of language analysis, the should can be explained with the help of so-called deontic predicators. These relate to the moral obligation of actions. A distinction must be made between the following variants:

- morally possible

- morally necessary

- morally impossible.

Morally possible actions are morally allowed, i. H. one can act like that. Morally necessary actions are morally required. Here one speaks of the fact that we should do something or have an obligation to do something. Morally impossible actions are morally forbidden actions that we are not allowed to perform; see also sin .

- The relationship to the good

The terms "good" and "should" are closely related but not identical. So we can find ourselves in situations where we can only choose between bad alternatives. Here it is ought that we choose the "lesser evil". Conversely, not all good things are also meant to be. This can e.g. B. be the case when the achievement of one good excludes another good. Here a weighing of interests must be carried out, which leads to the renunciation of a good.

justice

The concept of justice has come into focus again since the intensive discussion about the “theory of justice” by John Rawls and especially since the current political debate about the tasks of the welfare state (emphasis on equal opportunities and performance versus distributive justice).

Like the term “good”, “just” is used in many different meanings. Actions, attitudes, people, relationships, political institutions and sometimes affects (the “just anger”) are described as just. Basically, a distinction can be made between a “subjective” and an “objective” use, whereby both variants are related to each other.

The subjective or better personal justice relates to the behavior or the basic ethical attitude of an individual. A person can act righteously without being righteous and vice versa. The Kantian distinction between legality and morality is related to this . From the outside, legal acts are in accordance with the moral law, but do not occur solely on the basis of moral motives. B. also out of fear, opportunism, etc. In the case of moral actions, on the other hand, action and motive coincide with one another. In this sense, justice is referred to as one of the four cardinal virtues .

The objective or institutional justice refers to the areas of law and state. This is always about duties within a community that affect the principle of equality. A fundamental distinction must be made between compensatory justice (iustitita commutativa) and distributive justice (iustitita distributiva). In compensatory justice, the value of a product or service comes to the fore. Distributive justice is about the worth of the people involved.

The justice of individuals and institutions must be seen in a close relationship to one another. Without just citizens, just institutions cannot be created or sustained. Unjust institutions, on the other hand, make it more difficult to develop the individual virtue of justice.

The concern of ethics is not limited to the issue of "justice". The virtues also include those that one has above all towards oneself (prudence, moderation, bravery). One of the ethical duties towards others is the duty of doing good (beneficientia), which goes beyond justice and is ultimately rooted in love . While justice is based on the principle of equality, it is the plight or need of the other in charity. This distinction corresponds to that between “iustitia” and “ caritas ” (Thomas Aquinas), legal and virtuous duties (Kant) or, in the present case, between “duties of justice” and “duties of charity” ( Philippa Foot ).

Ethical theories

Classes of ethical or moral-philosophical theories can be differentiated according to which criteria they are based on for determining what is morally good. The moral good can be determined by:

- the consequences ( teleological ethics , consequentialism );

- the behavioral dispositions , character traits and “virtues” ( virtue ethics );

- the intentions of the agent ( ethics of conviction );

- objective moral facts, for example concerning objective moral goods or action assessments ( deontological ethics );

- the optimization

- the interests of those affected (preference- utilitarian ethics),

- happiness ( eudaemonia )

- or welfare .

A wide variety of combinations and finer moral-theoretical determinations are represented.

Teleological or deontological ethics

The various ethical approaches are traditionally distinguished in principle according to whether they focus on the action itself (deontological ethics approaches) or on the consequences of action (teleological ethics approaches). The distinction goes back to CD Broad and was made famous by William K. Frankena . Max Weber's division into ethics of conviction and ethics of responsibility goes in the same direction , which he understood as a polemic against ethics of conviction.

Teleological Ethics

The Greek word “telos” means something like completion, fulfillment, purpose or goal. Under teleological ethics is therefore those theories that focus their attention on specific purposes or goals understands. They claim that actions should strive for an end that is good in a broader understanding. The content of this goal is determined in quite different ways by the various directions.

Teleological ethics give valuative sentences priority over normative sentences. For them, goods and values are in the foreground. Human actions are of particular interest insofar as they can be a hindrance or a benefit to achieving these goods and values. "An action is to be carried out and only if it or the rule under which it falls causes a greater preponderance of the good over the bad, presumably will or should bring about, than any achievable alternative" (Frankena).

Within teleological ethics approaches, a distinction is made between “onto-teleological” and “ consequentialist -teleological ” approaches.

In onto-teleological approaches - classically represented by Aristotle - it is assumed that the good to be striven for is in a certain way inherent in man himself as part of his nature. It is required that humans should act and live in a way that corresponds to their essential nature in order to perfect their species-specific disposition in the best possible way.

In consequentialist-teleological approaches, on the other hand, the assumption is no longer that human existence is ultimately predetermined. The goal to be striven for is therefore determined by a benefit that lies outside the acting subject. This approach is already represented in antiquity ( Epicurus ) and later in its typical form by utilitarianism .

Deontological ethics

The Greek word "to deon" means "the decent, the duty". Deontological ethics can therefore be equated with ought ethics . They are characterized by the fact that the consequences of action do not have the same meaning as in teleological ethics. Within the deontological ethics, a distinction is often made between act deontological (e.g. Jean-Paul Sartre) and rule deontological concepts (e.g. Immanuel Kant). While rule deontology identifies general types of action as prohibited, permitted or required (cf. e.g. the prohibition of lying or the obligation to keep promises), according to act deontological theories , the deontological moral judgment relates directly to specific modes of action in particular situations.

In deontological ethics, normative sentences have priority over valuative sentences. For them, commandments , prohibitions and permissions form the basic concepts. Human actions come to the fore, as only they can violate a norm. Robert Spaemann characterizes them as "moral concepts [...] for which certain types of action are always reprehensible without considering the other circumstances. B. the deliberate direct killing of an innocent person, the torture or the cohabitation of a married person ”.

Criticism of the distinction

The distinction between teleological and deontological ethics has been called questionable by some critics. In practice, approaches are rarely found that can be clearly assigned to one of the two directions.

A strict deontological ethics would have to succeed in showing actions that "in themselves", completely detached from their consequences, could be described as immoral and "in themselves bad". This would then have to be done or omitted “under all circumstances” according to the saying “Fiat iustitia et pereat mundus” ( “Justice be done, and should the world perish because of it” , Ferdinand I von Habsburg ). Well-known examples of such actions are the “killing of innocents” or the lie, which is inadmissible according to Kant. In the eyes of the critics, there is often a “ petitio principii ” in these cases . If z. B. the killing of innocent people is defined as murder and this in turn is defined as an immoral act, it can of course in any case be described as “inherently bad”. The same applies to the lie if it is called the unauthorized falsification of the truth.

Especially in the analysis of ethical dilemma situations , in which only the choice between several evils is possible, shows that it should hardly be possible to describe certain actions as "morally bad" under all circumstances. According to a strict deontological ethic, the “choice of the lesser evil” would not be possible.

Strictly teleologically argumentative approaches to ethics are criticized for making what is ethically ought dependent on non-ethical purposes. This leaves the question unanswered as to why we should pursue these purposes. A weighing of interests is thus made impossible, since the question of what a or the better “good” is can only be clarified if general principles of action have been defined beforehand. In many teleological approaches, these principles of action would simply be tacitly assumed, e.g. B. in classical utilitarianism, for which the acquisition of pleasure and the avoidance of discomfort are the guiding principles of any impact assessment.

Want and should in approaches to ethics

Ethical positions can also be differentiated according to how what is ought results from a certain will.

| Ethical position | Representative | The standard of what is ethically ought is ... |

|---|---|---|

| divine command theorists | ... the will of God | |

| Intuitionism | Ross , Audi | ... the common sense and desire of all people |

| Position of generalizability / categorical imperative | Kant, singer | ... the will of every individual himself, if he has to assume that the rules he has chosen for his own actions are also followed by all other individuals at the same time |

| Position of general will | Rousseau | ... the will of individuals themselves when they jointly decide on laws that apply to all in a situation of social equality |

| Consensus theory position / discourse theory | Habermas | ... the will of the individuals themselves when they have to agree on rules for dealing with one another on a permanent basis, free from any coercion |

| Position of greatest general benefit or typical variants of utilitarianism | Bentham | ... the sum of the equally informed wills of the individuals themselves |

| Contract theory position | Buchanan, Scanlon, Gauthier | ... the will of the individuals themselves if they had to contractually agree on rules for dealing with one another |

| Position of self-interest broken by ignorance | Rawls , | ... the will of a self-interested, rational individual who designs a social order without knowing which position he himself will take in this order |

| Position of the reversed roles / golden rule | Hare | ... the will of every individual himself if he assumes when formulating rules for dealing with one another that he himself is in the position of the other concerned |

| Position of reversibility | Rawls, Baier | ... the will of every individual himself if, when determining rules for dealing with one another, he hypothetically assumes that he himself is in the position of the comparatively worst off |

| Position of the supra-individual entities (race, people, nation, class) | ... the will of the authoritative collective | |

| Legal positivism | ... the will of the respective legislative sovereign | |

| Reason Doctrine | ... the insight of the rational on the basis of reasonable deliberation | |

| egoism | Max Stirner | ... the will of every individual himself, if he is informed and takes a long-term time horizon into account |

The positions listed are on different logical levels and are therefore not logically mutually exclusive. So is z. B. the connection of a religious position with an intuitionist position possible. A connection between the position based on consensus theory and a utilitarian position is also conceivable, assuming that a consensus on the correct norm can only be established if the benefit (wellbeing) of each individual is taken into account in the same way.

It should also be noted that some of these approaches expressly do not claim to be comprehensive ethical concepts. B. only concepts for assessing whether a society is set up fairly from a political and economic point of view; z. B. with John Rawls, in contrast to more comprehensive approaches, which also concern questions of private, individual ethics - for example, whether there is a moral obligation to lie, if exactly this is necessary to save a human life (and if without this lie no one else would be saved instead). Also z. B. Habermas does not answer this question “in terms of content”, but his concept also includes the area of such questions, in that it “formally” postulates that what is correct in this question is what everyone who would take part in an informal and at the same time sensible discourse on it as binding for everyone to find out about it and accept it.

Correct content and formal binding nature of standards

When asked why individual A should obey a certain norm of behavior N, there are two kinds of answers.

One type of answer relates to an institution or process that set the standard . Examples for this are:

A should obey N because ...

- ... A has promised this,

- ... the deceased stipulated this in his will,

- ... the applicable law prescribes this,

- ... the owner wants it that way,

- ... it was decided by the majority, etc.

The other type of answer relates to the content of the norm . Examples of this type of response are:

A should obey N because ...

- ... N is fair,

- ... N is the best for everyone,

- ... observing N leads to the greatest good of all,

- ... N corresponds to human dignity etc.

Obviously these reasons are on two different levels, because one can say without logical contradiction: “I consider the resolution of the parliamentary majority to be wrong in terms of content, but it is still binding for me. As a democrat, I respect the decisions of the majority. "

One can distinguish the ethical theories according to how they deal with the tension between the level of procedural setting of binding norms and the level of argumentative determination of correct norms.

On the one hand, there are the decisionists on the very outside . For them, only the binding setting of norms is significant. They deny that it is even possible to speak of correctness of content and knowledge of the correct norm with regard to norms.

The main problem of the decisionists is that there can be no justification for resistance to the norms that have been set, because “binding is binding”. Furthermore, decisionists cannot explain why one standard-setting procedure should be preferred to any other procedure.

On the other hand are the ethical cognitivists on the very outside . For them, the problem of ethical action is solely a problem of knowledge that can be solved by obtaining relevant information and evaluating it according to suitable criteria. It is not possible for them to legitimize norms through procedures.

The main problem of the cognitivists is that even in the case of scientific disputes of opinion, definitive findings that could serve as a basis for social coordination are often not obtained. Therefore, binding and sanctioned norms are also required, which make the actions of others predictable for each individual.

Epistemological and metaphysical problems of ethics

To be and should

Teleological ethics are usually goods ethics; they designate certain goods (e.g. "happiness" or "pleasure") as good for people and therefore worth striving for.

David Hume has already raised the objection that the transition from statements of being to statements of should be illegal (" Hume's Law "). Under the heading of “ naturalistic fallacy ”, George Edward Moore raised closely related questions that, strictly speaking, are not the same.

Hume criticizes the moral systems known to him,

“… That instead of the usual combinations of words with 'is' and 'is not', I no longer come across a sentence in which there is not a 'should' or 'should not'. […] This should and should not express a new relationship or claim, so it must necessarily be considered and explained. At the same time, a reason must be given for something that otherwise seems quite incomprehensible, namely for how this new relationship can be traced back to others who are quite different from it. "

For Hume, logical conclusions from what is to what ought to be are inadmissible, because no completely new meaning element such as the ought can be derived from actual sentences through logical transformations.

As the positivists later emphasized, an epistemological differentiation must be made between actual sentences and should sentences because of their different relationship to sensory perception. While the sentence “Peter was at the train station at 2 p.m.” can be checked, i.e. verified or falsified, through intersubjectively matching observations, the sentence “Peter should be at the train station at 2 p.m.” cannot be justified or justified by means of observation and logic alone refute.

The epistemological distinction between being and ought is the basis of modern empirical sciences. Anyone who does not accept this distinction must either postulate a being that cannot be perceived directly or indirectly, or he must consider what is ought to be perceptible to the senses. Both positions have so far lacked an intersubjective verifiability.

The supposed derivation of ethical norms from statements about beings is often only possible through the unnoticed exploitation of the normative-empirical ambiguity of terms such as “essence”, “nature”, “determination”, “function”, “purpose”, “sense” or “ Goal achieved.

The word “goal” describes what a person actually strives for (“his goal is the diploma”). However, the word can also denote what a person should strive for (“He who is only oriented towards material things misses the true goal of human existence”).

The unnoticed empirical-normative ambiguity of certain terms then leads to logical fallacies such as: “The essence of sexuality is reproduction. So contraception is not allowed because it does not correspond to the essence of sexuality. "

The logical distinction between being and ought, however, by no means implies that an ethics based on reason is impossible, as is expressed by representatives of both logical empiricism and idealism . It is true that no ethics can be based on empiricism and logic alone , but it does not follow that there are no other generally comprehensible criteria for the validity of ethical norms. A promising example of a nachpositivistische ethics is based on the criterion of unforced consensus discourse ethics .

With the statement that the ought cannot be logically deduced from being, the justification of norms does not become hopeless. Because besides the statements of being and the normative sentences there are expressions of will. The expression of will of a person: “I don't want to be disturbed by anyone in the next hour” includes the norm: “Nobody should disturb me in the next hour”. It is the task of ethics to determine generally valid intentions or norms and to justify them in a comprehensible manner.

The logical distinction between actual sentences and should sentences is seen primarily by representatives of idealistic positions as an impermissible separation of being and ought, and it is objected that it is based on a shortened concept of being. Vittorio Hösle argues that the ought can only be strictly demarcated from the real, empirical being, "... an ideal being that is not posited by humans is just as little denied to the ought as a possible principle function over empirical being". It can be seen as a human task “to come to terms with the fact that being is not what it should be”. What is ought to be and, as such, is already the principle of being:

"But if the project of ethics is to have a meaning, then being must be structured in a certain way: It must contain beings who are at least capable of the knowledge of what is ought, yes, in which this knowledge - despite all the resistance from different interests - is not without influence on their actions. That assumptions about reality follow from the validity of the ought is by no means a trivial assumption and m. E. to be understood only within the framework of an objective idealism, according to which factual existence is at least partially based on ideal structures. "

The possibility of a teleological ethics seems fundamentally called into question with the logical distinction between statements of being and ought to be. From the point of view of the classical position of realism with regard to ethics, especially natural law, it is precisely being from which the ought must be derived, since there is no alternative to being (apart from nothing). Because the good is what is just, that is, what is just or corresponding to the respective being, the essence of being must first be recognized and the requirement of what is ought to be derived from it logically.

The problem of evil

Despite the partly apocalyptic historical events of the 20th century, the term " evil " is rarely used in everyday language. Instead, the terms “bad” (“a bad person”) or “wrong” (“the action was wrong”) are mostly used. The word “evil” is generally considered to be suspicious of metaphysics and, due to the general dominance of scientific thinking, as outdated.

In the philosophical tradition, evil is viewed as a form of evil . Leibniz's distinction between a metaphysical (malum metaphysicum), a physical (malum physicum) and a moral evil (malum morale) has become classic . The metaphysical evil consists in the imperfection of all beings, the physical evil in pain and suffering. These evils are adversities that have their origin in nature. They are not "bad" because they are not the result of (human or, more generally, spiritual) will. The moral evil, on the other hand, consists in the non-conformity of an action with the moral law or natural law. As Kant emphasizes, only “the type of action, the maxim of the will, and therefore the person acting himself” can be evil. Evil is therefore to be understood as the performance or, better, failure of the subject.

Reductionist attempts to explain

The behavioral research leads the evil to the general "fact" of aggression back. This is simply a component of human nature and as such is morally irrelevant. Therefore Konrad Lorenz also speaks of the "so-called evil". Critics accuse this explanation of a reductionist approach. It overlooks the fact that man is given the opportunity on the basis of freedom to take a position on his own nature.

In philosophy, Plato asked himself how evil is possible at all. Evil is only done because someone mistakenly believes that he (or someone) will benefit from it. So he wants the benefit associated with evil. No one could reasonably want evil for its own sake:

Socrates: So it is clear that those who do not know it do not desire what is evil, but rather what they consider good while it is evil; so that those who do not know it and consider it good, obviously actually desire the good. Or not?

Socrates: And further: Those who desire evil, as you assert, while they believe that evil harms him to whom it is bestowed, do not they realize that they will be harmed by it?

Meno: Necessary.

Socrates: But do they not consider those who suffer harm to be miserable if they suffer harm?

MENON: That is necessary too.

Socrates: But don't they consider the poor to be unhappy?

Meno: I think so.

Socrates: Is there a man who wants to be miserable and unhappy?

MENON: I don't think so, Socrates.

Socrates: So no one wants evil, Meno; if otherwise he does not want to be one. For what does being miserable mean other than desiring and possessing evil? "

Non-reductionist attempts at explanations

This understanding, which was still widespread in antiquity, that evil could be overcome by reason, is, however, called into question by historical experiences, especially those of the 20th century. In the eyes of many contemporary philosophers, these teach that man is quite capable of willing evil for his own sake.

First of all, egoism can be identified as the motive for evil. It manifests itself in many varieties. In its harmless variant, it shows itself in the ideal of a self-centered satisfaction of needs. In this form, it ultimately also represents the "contractual basis" of utilitarianism, which wants to create nothing more than a balance of interests between individuals. As historical experience shows, this aspect does not yet hit the real core of evil. This only becomes visible when the satisfaction of one's own needs is no longer in the foreground:

“The actual structure of evil, however, […] only shows up where this utilitarian reference is not leading, but where the pointless, even absurd joy of pure destruction predominates. Only here do you discover the uncanny traits of the human ego: the rush of power of destruction is enjoyed "

According to Kant, the cause of this “radical evil” is to be seen neither in sensuality nor in reason, but in a “perversion of the heart” in which the ego turns against itself:

“The malevolence of human nature is therefore not both malice, if one takes this word in a strict sense, namely as a disposition (subjective principle of the maxims) to include evil as the mainspring of evil in one's maxim (because it is diabolical); but rather wrongness of the heart, which, because of the consequence, is also called an evil heart. "

Kant's basic idea of the self-contradiction of the ego as the cause of evil is deepened again above all in the philosophy of idealism . Schelling differentiates between a “self-will” that denies all ties and a “universal will” that takes shape in relationships. The possibility of evil consists in the fact that self-will opposes its integration into universal will.

“The principle, insofar as it comes from the ground and is dark, is the self-will of the creature, which, however, if it has not yet been raised to perfect unity with the light (as the principle of understanding) (cannot grasp it), mere addiction or Desire, d. H. blind will is. The mind opposes this self-will of the creature as a universal will that uses it and subordinates itself as a mere tool. "

The radical evil causes an overthrow of the order in myself and in relation to others. It takes place for its own sake, because "just as there is an enthusiasm for good, there is also an enthusiasm for evil".

According to the classical teaching (Augustine, Thomas Aquinas etc.), evil itself is ultimately insubstantial. As a privative opposition to the good, it consists only in a lack (of good). In contrast to the absolutely good (God) there is no such thing as absolutely bad.

Enforcement problem

The enforcement problem of ethics is that the insight into the correctness of ethical principles may exist, but it does not automatically follow that people also act in an ethical sense. The insight into the right action requires additional motivation or compulsion.

The problem is explained by the fact that ethics on the one hand and human self-interest as egoism on the other hand often form a contradiction. The enforcement problem is also gaining a new dimension through globalization , which leads to a neo-modern ethic .

example

The fact that the people in country X are hungry and that they should be helped, and that it is morally necessary to help them, will not be denied. The insight to do so, to give up a large part of one's wealth for it, will only exist to a significant extent when an additional motivation emerges, such as the imminent danger of migration to one's own country due to hunger.

The enforcement problem also shows up in a different way in upbringing, for example when firmly internalized rules of conduct later meet developed ethical principles.

Possible solutions

Findings from evolutionary game theory allow conclusions to be drawn that the assertion problem can be solved through self-penetration. This view was first represented by representatives of the New Institutional Economics . Eirik Furubotn and Rudolf Richter pointed out that building a reputation can be a dominant game strategy.

See also

literature

Philosophy Bibliography : Ethics - Additional references on the topic

- Introductions

- Arno Anzenbacher : Introduction to Ethics. 3. Edition. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-491-69028-5 (easy to read introduction)

- Dieter Birnbacher : Analytical Introduction to Ethics. De Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2003, ISBN 3-11-017625-4 (systematic presentation of normative ethics from the point of view of an analytical philosopher ; modern approaches are in the foreground)

- Dagmar Fenner: Ethics. How should i act? UTB, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8252-2989-4 (well-structured introduction, somewhat like a textbook)

- Dietmar Hübner : Introduction to Philosophical Ethics . UTB, 2nd edition, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8252-4991-5 (clear systematics with historical depths)

- Annemarie Pieper : Introduction to Ethics. 5th edition. Francke, Tübingen et al. 2003, ISBN 3-8252-1637-3 , ISBN 3-7720-1698-7 (much-cited introduction to ethics)

- Louis P. Pojman, James Fieser: Ethics. Discovering Right and Wrong. Wadsworth Pub. 2008, ISBN 978-0-495-50235-7 . (excellent, very clear, first introduction, often used as a textbook) (table of contents) ( MS Word ; 177 kB)

- The blue Rider. Journal of Philosophy . Special issue: ethics. No. 3, 1995. Verlag der Blaue Reiter, ISBN 978-3-9804005-2-7 .

- Karl Hepfer. Philosophical ethics. An introduction. Göttingen 2008 (UTB 3117), ISBN 978-3-8252-3117-0 (very clear and easy-to-read presentation of all common reasoning models)

- Michael Quante: Introduction to General Ethics. Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-15464-9 (textbook-like work with summaries, reading tips and exercises at the end of each chapter; goes into detail on metaethical questions)

- Hans Reiner : Ethics. An introduction. Study edition, PAIS-Verlag, Oberried 2010, ISBN 978-3-931992-27-9 (easy to understand introduction)

- Andreas Vieth: Introduction to Philosophical Ethics. Münster / Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-7380-2658-0 , PDF (topic-oriented, metaethical, visual topic preparation, textbook)

- Overall representations

- Marcus Düwell, Christoph Hübenthal, Micha H. Werner (eds.): Handbook Ethics. 2nd act. Edition. Metzler, Stuttgart et al. 2006, ISBN 3-476-02124-6 (currently the standard handbook on ethics; contains a historical and a conceptual part; broad consideration of the current discussion; sometimes very demanding)

- Hugh LaFollette (Ed.): Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory. Blackwell, Oxford 2000. ( Table of Contents )

- Friedo Ricken : General ethics. 4th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-017948-9 (very well-founded and demanding; attempts a synthesis of Aristotelian and Kantian approaches with borrowings from analytical philosophy)

- Hugh LaFollette (Ed.): Ethics in Practice: An Anthology. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-470-67183-2 .

- Lexicons and basic terms

- Otfried Höffe (Ed.): Lexicon of Ethics. 6th edition. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-47586-8 (the standard lexicon for the introduction to the terms of ethics)

- Gerhard Schweppenhäuser : Basic concepts of ethics as an introduction. 2nd Edition. Junius, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-88506-632-7 (concentrates on the treatment of central basic concepts of ethics)

- Ethics in science

- Hans Lenk (Ed.): Science and Ethics , Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-15-008698-1

Web links

- Karl-Heinz Brodbeck : Ethics and Morals. a critical introduction. ( Memento of June 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.5 MB) Verlag BWT, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-9808693-1-8 . (Free introductory e-book)

- Roger Crisp: Ethics. In: E. Craig (Ed.): Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy . London 1998.

- James Fieser: Ethics. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Henry S. Richardson: Moral Reasoning. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Individual evidence

- ^ Lexicon Philosophy - Hundred Basic Concepts , Reclam, 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Cicero: De fato 1; Moral, moral, moral philosophy. In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy . Volume 6, p. 149.

- ↑ Viktor Cathrein SJ : Moral philosophy. A scientific exposition of the moral, including the legal, order. 2 volumes, 5th, newly worked through edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1911, pp. 1-6 ( concept of moral philosophy ).

- ↑ See A Greek-English Lexicon 9. A. (1996), p. 480.766.

- ↑ Viktor Cathrein: Moral Philosophy. A scientific exposition of the moral, including the legal, order. 2 volumes, 5th, newly worked through edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1911, pp. 17-27 ( History of Moral Philosophy ), here: pp. 24 f., And p. 27 ( Classification of Moral Philosophy ).

- ^ FH Bradley: Why should I be moral? In: Ethical Studies. The Clarendon Press, Oxford 1876.

- ↑ Kurt Bayertz: Why be moral at all? CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52196-7 .

- ^ Friedo Ricken: General ethics. P. 96.

- ↑ § 17 StGB

- ↑ See Ricken: Allgemeine Ethik. P. 136f.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas : Summa theologica .

- ^ Ricken: General Ethics. P. 84.

- ↑ Aristotle : Nicomachean Ethics . Politics .

- ↑ CD Broad: Five Types of Ethical Theory. London 1930.

- ^ William K. Frankena: Ethics. 2nd Edition. Englewood Cliffs 1973, p. 14, translated in Albert Keller: Philosophy of Freedom. Styria, Graz 1994, p. 212.

- ^ Robert Spaemann: Christian ethics of responsibility. In: Johannes Gründel (Hrsg.): Living out of Christian responsibility, 1. Foundations. Düsseldorf 1991, p. 122.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Albert Keller: Philosophy of Freedom. Styria, Graz 1994, ISBN 3-222-12294-6 .

- ↑ See Mark Murphy: Theological Voluntarism. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . ; Michael W. Austin: Divine Command Theory. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . .

- ^ Vittorio Hösle: Morals and Politics . Foundations of Political Ethics for the 21st Century. Beck, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-406-42797-9 , p. 127.

- ^ Hösle: Morality and Politics. P. 242.

- ↑ See Kant: KpV. P. 106.

- ↑ Cf. Walter Schulz : Philosophy in the changed world . 7th edition. Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-608-91040-9 , p. 723ff.

- ^ Plato: Meno . 77a-78b.

- ↑ Schelling: Philosophical investigations into the nature of human freedom and the objects connected with it. P. 468.

- ↑ A. Schopenhauer: The two basic problems of ethics. 1839/40.

- ↑ Helga E. Hörz and Herbert Hörz : Is egoism immoral? Basics of a neo-modern ethic. trafo Verlagsgruppe, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86464-038-4 .

- ^ HJ Niemann: The strategy of reason. Rationality in Knowledge, Morality and Metaphysics. Vieweg, Braunschweig et al. 1993, ISBN 3-528-06522-2 .

- ^ R. Richter, E. Furubotn: New Institutional Economics Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, p. 277, ISBN 3-16-148060-0 .