Relations between Japan and the United States

|

|

|

|

|

| United States | Japan |

The Japan-United States relations are characterized by close economic and military cooperation and intensive cultural exchange. Both countries have been allied with each other since the end of World War II . For Japan , the alliance with the United States is a central element of its security and defense policy; for the USA, Japan is considered to be a major non-NATO ally and the region's most important ally. Both countries are economically closely intertwined: 22.6% of Japanese exports went to the United States in 2006, which corresponds to 8% of imports. More than a third of all foreign direct investment in Japan comes from the US. At the cultural level there are diverse institutional and personal contacts, and the popular cultures of both countries influence one another.

Historical background

First contacts

The first indirect trade relations between North America and Japan existed during the era of the Namban trade in the early 17th century; however, there was no direct contact between Japan and the European colonies that later became part of the United States, as exchanges were always handled through European intermediaries.

Some Spanish ships reached Japan en route from Nueva España , now Mexico . The sailors Christopher and Cosmas were the first known Japanese to reach the American continent on board Spanish ships in 1587. In 1610 Tanaka Shōsuke traveled with 20 other Japanese envoys parts of America on the Japanese ship San Buena Ventura , which had been built with the help of William Adams based on European models. In 1611, the Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno made a return visit to establish formal relations between California and Japan.

In return for Vizcaínos mission, the embassy of the samurai Hasekura Tsunenaga traveled to California in 1613 on board the Japanese ship San Juan Bautista , from there to Nueva España and finally to Europe in 1614.

In 1650, the ruling Tokugawa passed the Sakoku laws and all foreign trade was suspended. Only the Dutch , Ryukyuans , Koreans and Chinese were allowed to enter the country under strict conditions. When the United States gained independence in the 18th century, there were no exchanges between the two states. For much of the 19th century, the USA, like the major European powers, endeavored to open up Japan and re-establish diplomatic and trade relations.

Early American expeditions to Japan

- In 1791, the American explorer John Kendrick landed with Lady Washington with William Douglas and Grace for 11 days on Kii-Ōshima , just under two kilometers south of the Kii Peninsula . He is the first American known to visit Japan.

- From 1797 to 1809 the Netherlands could not send ships to Japan because of their conflict with the United Kingdom during the Napoleonic Wars and asked the US to trade some American ships under the Dutch flag in Dejima .

- In 1837, Charles W. King , a Guangzhou businessman , saw an opportunity to open up Japan to foreign trade by bringing back to Japan three Japanese sailors who had been shipwrecked off the Oregon coast a few years earlier . He took the unarmed merchant ship Morrison to Uraga Strait , but had to turn back unsuccessfully after the ship was caught under fire several times.

- Commander (frigate captain) James Biddle anchored two ships in Edo Bay in 1846 on behalf of the US government to open Japan to trade ; one of the ships was armed with 72 cannons. However, his demands for a trade deal were not answered.

- In 1848, Captain James Glynn sailed for Nagasaki and conducted the first successful negotiations between an American and Japan during the Sakoku . Upon his return to North America, Glynn recommended to the US Congress that any negotiations to open up Japan should be accompanied by a show of strength. This paved the way for the later missions of the Commodore (Flotilla Admiral) Matthew Perry .

Commodore Matthew Perry and the "Black Ships"

The first visit 1852-1853

In 1852 Perry set out for Japan with a squadron from Norfolk to sign a trade agreement. On July 8, 1853, on board a steamship with a black hull, he anchored with the ships Mississippi , Plymouth , Saratoga , and Susquehanna in the port of Uraga (today: Yokosuka ) near Edo and met with representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate. These instructed him to continue to Dejima, where the Sakoku laws allowed limited trade with the Dutch. However, Perry refused, requested permission to deliver a letter from US President Millard Fillmore , and threatened the use of force if he refused. Since Japan had hardly imported modern technology for centuries, the Japanese military was in no position to fight back against Perry's ships. In Japan, these “black ships” became symbols of the technical superiority of the West and the threat of colonialism to Japan.

The Japanese government had to accept Perry's request to be allowed to go ashore to avoid a bombing. On July 14th, he landed in Kurihama (near today's Yokosuka ) and handed the letter to the representatives present. He then went to China and announced that he would come back later for an answer.

The second visit in 1854

Perry returned in February 1854 with twice as many ships. The representatives of the Japanese government awaited him with an agreement that fulfilled almost all of the demands of President Fillmore's letter. Perry signed the Treaty of Kanagawa on March 31 and departed on the mistaken belief that he had signed a contract with representatives of the Tennō .

The Japanese Legation to the United States

Main article: Japanese legation to the United States in 1860

Six years later, the Shogun sent the Japanese warship Kanrin Maru on a mission to the United States. It was his intention to demonstrate to the world that Japan now possessed western navigation and shipbuilding technology. On January 19, 1860, the Kanrin Maru left Uraga Street for San Francisco . In addition to Captain Katsu Kaishū , the embassy included Nakahama Manjirō and Fukuzawa Yukichi . On board American ships, the Legation traveled on to Washington, DC via Panama

The official aim of the mission was to send a Japanese embassy to the United States for the first time and to sign the new Japan-US friendship and trade treaty . The delegation also tried unsuccessfully to revise some of the clauses in the unequal contracts concluded with Matthew Perry.

Relationships in the Meiji Period

During the Meiji period , Japan pursued rapid industrialization and social modernization, drawing primarily on Western models. The most important partners were Great Britain and Prussia (or the German Empire ), but there was also increasing exchange with the United States. Many ancestors of Japanese Americans emigrated to the United States during this time. Conversely, many American scholars came to Japan; one of them was the English professor Horace Wilson , to whom the Japanese owe their national sport when he introduced baseball in Japan in 1872 .

At the government level, Japan first endeavored to revise the unequal treaties, and later to find a compromise with the major Western powers to secure the expansion policy in East Asia. Through the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, Japan was bound to the Western powers and fought on the side of the Allies in the First World War .

Increasing tension between the world wars

Japan was only partially satisfied with the outcome of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 : Although it was allowed to keep the German colonies in the Pacific and Qingdao , the racial equality clause originally adopted with eleven votes was not included on the initiative of US President Woodrow Wilson . Tensions also developed in other areas: at the Washington Naval Conference , Japan saw itself at a disadvantage compared to the USA and Great Britain in terms of armament, and the Japanese expansionist efforts in China, despite the Lansing-Ishii Agreement and the Nine Powers Agreement, increasingly challenged the USA, which continued to do so adhered to the open door policy in vain .

During the time of Taishō democracy in the 1920s, parts of both societies continued to strive for good relations. B. in the exchange of Friendship Dolls or the US aid after the Great Kanto earthquake manifested. However, the militarization on the Japanese side and the isolationist attitude of the USA before and during the world economic crisis led to increasing alienation. Racist perspectives also contributed to the cooling: On the American side, laws were passed against land purchase and immigration by Asians.

As the military took control of Japan in the 1930s, the two countries moved further apart. After the beginning of the war with China in 1937, the relationship was largely characterized by distrust and rivalry. US sanctions such as the scrap embargo, incidents such as the Panay incident , Japanese war crimes such as the Nanking massacre, and finally Japan's accession to the Axis powers increased expectations of a military confrontation on both sides. With the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese military put an end to all diplomatic efforts and drew the USA into the Pacific War , which only ended with the surrender of Japan in 1945 after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the USSR entered the war .

Political Relations

Occupation after World War II

After the end of World War II , Japan was occupied by the Allies under the leadership of the United States; Troops from Australia, British India, the United Kingdom and New Zealand also contributed. For the first time in recorded history, the Japanese islands were occupied by a foreign power.

The occupation formally ended with the Peace Treaty of San Francisco , which was signed on September 8, 1951 and entered into force on April 28, 1952.

1950s: After the occupation

With the end of the occupation in April 1952, Japan and the United States were for the first time equal partners, which was legally recorded in the Treaty of San Francisco. However, equality was initially only formal; for in the early post-war period Japan was heavily dependent on American economic and military aid. In 1954 Japan achieved a balance of payments surplus with the US for the first time , mainly due to the return of US military and aid spending to Japan.

The feeling of dependency among the Japanese people diminished as the devastating aftermath of World War II gradually faded into the background and trade with the United States increased. Economic reconstruction boosted self-esteem and created a need for greater independence from American influence. During the 1950s and 1960s, this was particularly evident in attitudes towards the military bases on the four main islands and on the Ryūkyū Islands , which, like the Ogasawara Islands (Bonin Islands), remained under US sovereignty even after the peace treaty was signed . In recognition of the public desire to return these areas, the United States gave up its control of the Amami Islands , the northern part of the Ryūkyū Islands, as early as 1953 . A firm promise to return Okinawa , which according to Article 3 of the peace treaty was to remain under US military administration for an indefinite period, was not made. The public sentiment was reflected in a resolution by the Japanese parliament in June 1956 calling for Okinawa to be returned to Japan.

The Japanese government had to balance between pressure from the left for detachment from the US and the need for military protection, which, given the final victory of the communists in (mainland) China and the Korean War, seemed essential for a West-bound Japan.

1960s: Military alliance and return of Okinawa

In 1959 bilateral talks began on a modified version of the 1952 Security Treaty . The Treaty on Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States was signed on January 19, 1960 in Washington, DC. When the ratification process of the treaty began in the Japanese parliament on February 5, this was the starting point for a massive wave of protests from the political left, which was mainly supported by the trade unions and student associations. In Shūgiin , the Japanese lower house, he was ratified on May 20; however, boycotts of the SPJ , the CPJ and large demonstrations and riots by students and trade unions prevented ratification in the upper house, the Sangiin . The turmoil continued: a planned visit by President Dwight D. Eisenhower was postponed (and never took place) after the motorcade was besieged by James Hagerty , his press secretary, during a June 1960 visit to Haneda Airport . Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke resigned on July 15; but only after the treaty entered into force on June 19. (After 30 days without a vote in the Sangiin, the vote in the Shūgiin was considered binding and the contract was automatically ratified.)

According to the security treaty, both sides were required to provide mutual assistance in the event of an armed attack on areas under Japanese administration. In accordance with the interpretation of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution at the time that Japan was not allowed to send troops overseas, direct support to the United States by Japanese troops was not intended. The treaty did not include the Ryūkyū Islands, which were still under US administration; however, an additional protocol stipulated that in the event of an attack on these areas, both governments would coordinate and take appropriate action. It was also agreed that changes to the stationing of US troops and their equipment should be coordinated in advance between the two governments. Agreements on deepening international cooperation and improving economic relations were also recorded. The new contract had a term of ten years; thereafter the contract can be terminated by either party with one year's notice.

The two countries worked closely to fulfill the United States' promise, enshrined in Article 3 of the peace treaty, that all war-acquired territories from Japan should be returned. In June 1968, the Ogasawara Islands (Bonin Islands) including Iōjima were returned. In 1968 and 1969 the continued occupation of Okinawa and the security treaty sparked another wave of protests from the left. The situation only calmed down after Prime Minister Satō Eisaku traveled to Washington in 1969; there he signed an agreement with President Richard Nixon that an agreement should be found for the return of Okinawa in 1972. After 18 months of negotiations, the contract for the return of Okinawa in 1972 was signed in June 1971.

The Japanese government's firm stance on the Security Treaty and the settlement of the return of Okinawa removed two issues from the political debate over US relations. Soon new topics dominated the discussion: When President Nixon announced his visit to China in July 1971, the Japanese government was surprised. Many Japanese were upset that they had not been consulted about such a fundamental change in foreign policy. A ten percent increase in US import tariffs in the following month - again without prior discussion - which hindered Japanese exports, caused further resentment. In December 1971, relations were further strained by the financial crisis following the revaluation of the Japanese yen .

The events of 1971 ushered in a new phase of relations, during which both sides reacted to changing global circumstances and political and economic tensions emerged, without, however, fundamentally endangering the close partnership. At the political level, the focus was on the US effort to induce Japan to make greater contributions to its own defense and regional security. In economic terms, Japan's growing export surplus caused irritation, which led to an ever greater imbalance in the bilateral balance of payments and trade - Japan's trade balance with the USA was positive for the first time in 1965.

1970s: closer security cooperation and first trade conflicts

The end of the Vietnam War with the US withdrawal in 1975 meant that the assessment of Japan's role in the security architecture of East Asia and its own defense came back on the agenda. US dissatisfaction with Japan's contribution was expressed in 1975 when Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger publicly criticized Japan. The Japanese government - bound by the constitution and strongly pacifist public opinion - slowly reacted to calls for an expansion of the self-defense forces . However, it steadily increased the defense budget and showed its willingness to contribute more to the maintenance costs of US military bases. In 1976, both countries formally established a subcommittee to the Consultative Council of the Security Treaty of 1960, which was supposed to deal with defense cooperation. This subcommittee developed new guidelines for military cooperation, according to which new joint operational plans were established in the event of an attack on Japan.

In response to the Allies' call for a stronger role for Japan, Prime Minister Ōhira Masayoshi developed a "comprehensive security and defense strategy to keep the peace". After that, Japan should work more closely with the United States to achieve more balanced cooperation and greater autonomy at the global level. This new policy was put to the test in November 1979 when 60 hostages were held in the US embassy in Tehran when Tehran was taken hostage. Japan condemned the incident as a violation of international law; at the same time, however, Japanese companies allegedly were willingly importing Iranian oil made available after the US import ban. This led to harsh criticism from the US government of the Japanese government's lack of sensitivity in allowing these imports. Japan then apologized and, like other US allies, participated in the sanctions against Iran.

As a result of this incident, the Japanese government made greater efforts to support US international policy “in the interests of stability and prosperity”. Japan responded quickly to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and imposed sanctions on the USSR. In 1981 Japan accepted calls from the US to take on greater responsibility for the maritime defense of Japan, to participate more in the US military presence in Japan, and to further expand the self-defense forces.

Japan sought to ease tensions in economic relations by agreeing to orderly market arrangements (OMRs) that set export quotas without the US increasing tariffs and other trade restrictions. In 1977 an OMR for color television was signed, before the textile trade had already been regulated in this way. Steel exports to the USA were also restricted in this way. However, there were other controversial issues such as the American restrictions on the development of Japanese reprocessing plants, the Japanese import restrictions in the agricultural sector (e.g. beef, oranges) and the strict regulation of the Japanese capital market.

1980s: Fear of the economic giant

With the election of Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro in 1982, a qualitatively new phase of US-Japanese cooperation seemed to begin. Officials in President Ronald Reagan's administration worked closely with their Japanese partners to develop a personal relationship between the two leaders based on shared views on security and foreign policy. Nakasone assured the US leadership of Japan's determination to stand together against the Soviet threat, to develop a coordinated policy for Asian trouble spots such as the Korean Peninsula and Southeast Asia, and to find a common position towards China. The Japanese government welcomed the increase in the US troop contingent in the western Pacific and even further expanded the self-defense forces . Even after Nakasone's reign, cooperation remained close, but the internal political turmoil of the late 1980s ( recruit scandal ) and the associated change of government hampered the development of close personal relationships between Reagan's successor George HW Bush and his Japanese counterparts.

An example of close cooperation was Japan's quick response to a US request for greater assistance after the cost of the military presence in Japan skyrocketed due to the rapid appreciation of the yen in the mid-1980s. The Japanese government was ready to compensate for the increase in costs. Another example was the willingness of Japan to concentrate its aid payments, at the request of the US, on countries that were of strategic importance to the West. Representatives from the United States expressed their satisfaction with the strategic support for countries such as Pakistan , Turkey , Egypt and Jamaica . Prime Minister Kaifu Toshiki's announcement in 1990 that he would support countries in Eastern Europe and the Middle East also followed this pattern. Despite complaints from Japanese businessmen and diplomats, the Japanese government also essentially supported the US policy towards China and Indochina and refrained from major aid projects as long as the conditions there were not compatible with the common interests of Japan and the US.

During the Gulf War 1980-88, the US government asked for assistance in guarding tankers in the Persian Gulf and in mine clearance operations. Instead, the Japanese government helped set up a navigation system in the Persian Gulf, made loans to Oman and Jordan, and expanded its contributions to the US military presence in Japan. The United States also expressed understanding for the constitutional situation that made it impossible to send Japanese troops; In some cases, however, it was noted that Tōkyō was unwilling to cooperate on sensitive issues.

However, the most important area where cooperation deteriorated progressively in the 1980s was economic relations. The US pushed Japan to open markets and deregulate in certain areas. The Japanese government was also unwilling to give in because of its close ties with interest groups. Since she did not want to strain relations with the USA either, she relied on lengthy negotiations that could drag on for years. In this way, it gave the domestic sectors concerned the opportunity to adapt and at the same time was able to weaken the corresponding market opening agreements. In the end, these were often vaguely worded and subsequently the subject of disputes over interpretation.

Despite the increasing economic interdependence, the relationship went into a crisis in the second half of the 1980s. The US administration continued to stress the positive aspects but also expressed an urgent need for a "new conceptual framework". The Wall Street Journal published a number of reports on the changing relationship and raised the question of whether close cooperation between the two countries was possible or desirable in the 1990s. In 1990, the Washington Commission on US-Japan Relations for the Twenty-first Century , in an assessment of public and public opinion, expressed concern that a "new orthodoxy of suspicion, criticism and considerable self-righteousness" could jeopardize close relationships.

The change in the relative strengths of the Japanese and American economies was particularly rapid in the 1980s. This affected not only the annual trade balance which was between $ 40-48 million, but in particular it led to a strong appreciation of the yen (especially after the Plaza Agreement in 1985), which gave Japan the opportunity to import more goods from the US and vice versa to invest significantly there. By the end of the decade, Japan had become the second largest foreign investor after Great Britain, which worried some Americans. In addition, Japan, with its economic power, now seemed able to invest in the high-tech areas in which the US was still world market leader. In contrast, the USA appeared to be disadvantaged by the high level of corporate debt and by public and private households, and by the low savings rate.

At the end of the 1980s, the increasing demands on the USSR with its internal and economic problems, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Eastern bloc led to a reassessment of the alliance by the governments of Japan and the USA. Both put security relations in the foreground and gave them priority over economic disputes. Some continued to stress the threat that the Soviet military presence in Asia posed to both countries: as long as the USSR does not confirm its moderate course in Europe by reducing troops in the Far East, the US and Japan should remain vigilant and operational. Increasingly, however, other positive aspects of security relations also came to the fore, in particular the deterrent effect against other potentially threatening forces, above all the Democratic People's Republic of Korea . At the same time, there were some voices in the USA who, in view of Japan's economic rise, saw the alliance as a means of keeping Japan's military potential under US control.

1990s: After the Cold War

In the 1990s, the future of US-Japanese relations seemed more uncertain than it had ever been since the end of World War II. As long-standing military allies and increasingly economic interdependencies, the United States and Japan worked closely in many areas to safeguard their international interests and democratic values.

Closer integration

Despite the upset at the end of the 80s, relationships had improved and intensified considerably over the past few decades. In 1990 the two economies together accounted for around a third of the global gross domestic product (GDP). Eleven percent of US exports went to Japan (the second largest share after Canada), 34% of Japanese exports went to the USA. In 1991, there was $ 148 billion in direct investment from Japan to the United States, and $ 17 billion in the opposite direction. $ 100 billion in US Treasuries were held by Japanese institutions, funding a significant portion of the budget deficit. In addition to the economic, there were diverse forms of scientific, technological, tourist and cultural exchange; and in both societies, the partner continued to be viewed as the most important ally in the Asia-Pacific region. And despite developments in the late 1980s, polls showed that majorities in both countries saw the alliance as vital.

In the environment after the end of the Cold War , the importance of economic as opposed to military power grew as a means of world politics. As a result, expectations of Japan grew to assume greater responsibility in international issues.

Changed public perceptions

With the decrease in the threat posed by the USSR, closer economic ties and the associated conflicts, the public perception of the alliance also changed in both countries, especially in the USA. There, Japan's economic power was increasingly perceived as a threat that was greater than the threat posed by the Soviet Union - a series of surveys in 1989 and 1990 confirmed this. At the same time, surveys of the Japanese public showed that they attributed the Americans' more negative view of the US's declining economic importance. In addition, the self-confidence grew to regulate one's own affairs without constant reference to the United States: Confidence in the reliability of the United States as a leading power was shaken.

In both countries new, "revisionist" perspectives on mutual relations developed. Some observers in Japan advocated a more independent course, since the US is too weak to keep up with global competition. On the American side, some warned of an uncontrollable economic giant.

Despite these shifts in emphasis, the public view of the relationship remained essentially the same: For Japan the USA continued to be the closest ally, guarantor of external security, most important economic partner and cultural point of reference; and most Americans continued to have a positive view of Japan, respecting Japan's successes, and advocating military support.

In a Gallup survey of "opinion leaders" carried out annually since 1960 on behalf of the Japanese Foreign Ministry , Japan remained the United States' most important partner in Asia, ahead of China, until 2009. In 2010, a majority of 56 percent of those surveyed considered China the more important partner for the first time. 90 percent of the “opinion leaders” considered Japan a reliable ally.

Market opening

With the end of the Cold War and the change of government in both countries, relations went through a period of uncertainty and tension. With the conclusion of the Uruguay Round of GATT negotiations, a number of issues were resolved: In view of the declining domestic rice production, Japan had for the first time agreed to imports on a limited scale; but the growing bilateral trade deficit in the US led to further demands by Washington for specific goals in opening up the market. After fifteen months of negotiations, the two governments signed an agreement on October 1, 1994 that opened three major markets for US imports: the insurance market, the telecommunications sector and the medical technology market. An agreement on cars and auto parts had failed for the time being, but should be concluded within thirty days.

In the new millennium: a stronger alliance

Relationships improved significantly in the late 1990s. The deflationary crisis in Japan after the bursting of the bubble economy , the upswing in the USA and the rise of China reduced the perceived threat to the Japanese economic power. After the end of the Soviet Union, the “rogue state” of North Korea and the coming great power China found new legitimacy for the alliance. And with the increasing willingness of the Japanese government to take part in military operations abroad, security cooperation intensified. Japan, for example, took part in the Iraq operation with a small contingent of troops - as in other countries of the “coalition of the willing” against the resistance of large sections of the population - and is included in the US anti-missile shield, with the North Korean missile tests providing a concrete justification for the government. Japan is sometimes referred to as "Great Britain of the Pacific" in security studies, and the extent to which this comparison is accurate is still the subject of scientific debate.

Diplomatic missions

The Japanese Embassy is located on Embassy Row in Washington, DC ; In addition, Japan has 14 consulates general, another one in Guam and two consulates in Alaska and Saipan .

The US embassy in Japan is now located in Akasaka in Tokyo's Minato district ; five American consulates are in Japan, plus five associated American Centers , which serve to maintain cultural relations.

Economic relations

Trade volume and direct investment

For the Japanese economy , the US has long been the most important trading partner: 20.12% of exports, 11.41% of imports (No. 2 to China), 21.3% of outgoing and 57.3% of incoming foreign direct investment Settled with the USA in 2007. Conversely, Japan is the fourth largest trading partner for the United States' economy, accounting for 5.4% of exports, 7.4% of imports, and the second largest trade deficit after China. The export goods of the USA mainly include industrial goods (machines, transport) and agricultural products (fish, meat, grain, soy); conversely, mainly consumer goods and semi-finished products (especially automobiles) are traded.

Decreasing tensions

After the increasing disputes over trade relations in the 1970s and 1980s, tensions have decreased significantly since the 1990s. For one thing, the deflationary crisis has slowed Japan's economic rise considerably, and China has replaced Japan as the largest net importer in the USA; on the other hand, reforms in Japan, such as the “Big Bang” liberalization of the financial market, have opened up important markets for American products. There are still some controversial issues, especially in the agricultural sector, which is protected by trade barriers on both sides - for example, the Japanese government has repeatedly used the BSE crisis to impose import bans on US beef. Overall, however, common interests dominate, which are occasionally expressed in joint initiatives in a multilateral context, such as in APEC or the WTO .

Military relations

The 1952 Security Treaty and its 1960 revision form the basis of military cooperation between the United States and Japan. According to the agreements, the military of both countries will work together in the event of an attack on Japan - Japan will not be allowed to send troops there in the event of an attack on the USA because of the pacifist constitution - and a number of military bases will allow the USA to maintain a permanent presence in the region, whereby Japan contributed to their maintenance (1995: around 5 billion dollars) and the United States informed the Japanese government about changes in the stationed contingents.

The two countries are also working together on the development and purchase of weapon systems. Until the 1960s, Japan received military aid from the USA, later the security treaty formed the basis for agreements on the purchase and licensing of sensitive technology as well as the exchange of intelligence and intelligence information and for coordination of the interoperability of weapon systems.

Crimes committed by members of the US military, such as crimes, continue to strain relationships and lead to public protests. E.g. the kidnapping and rape of a twelve-year-old girl by three soldiers in Okinawa in 1995 or the murder of a taxi driver in Yokosuka by a Nigerian serving in the Navy in 2008.

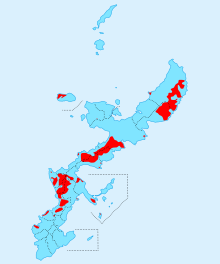

Ryūkyū Islands

The Ryūkyū Islands were placed entirely under Japanese sovereignty in 1972; however, the US government retained the right to station troops, and to date around 20% of the area of the main island of Okinawa is military territory. About 30,000 American soldiers are stationed there. This concentrated presence has helped Okinawa become a center of opposition from US bases and pacifist demonstrations.

United States Forces Japan

The US troops stationed in Japan are organized as United States Forces Japan (USFJ) and are subordinate to the United States Pacific Command . In 2007 over 33,000 soldiers were stationed in Japan, mainly on Okinawa and some bases on Honshū and Kyūshū . Of these, over 14,000 were members of the US Marines , over 13,000 of the Air Force , almost 4,000 members of the Navy and almost 2,000 Army soldiers.

In 1992 there were still over 50,000 soldiers, and that was already significantly fewer than the contingent stationed in Japan during the Cold War. During the 1990s, the US had promised to keep at least 100,000 soldiers stationed in East Asia over the long term to ensure the security of Japan, Taiwan and South Korea (where about as many soldiers are stationed as in Japan).

Joint operations and exercises

Since the establishment of common defense guidelines in 1978, the two armed forces have been working closely together on an ongoing basis. This also includes long-term joint exercises by the USFJ and the ground self-defense forces . The marine self-defense forces have also carried out joint exercises with the US Navy since 1955 ; In 1980 they were allowed to take part in the RIMPAC maneuver for the first time (together with Australia, Canada and New Zealand), to which they, like the South Korean Navy and other Pacific allies, are now regularly invited. The Air Self-Defense Forces have now held numerous defense, rescue and command exercises with the US Air Force . The coast guards of both countries have already carried out maneuvers together.

Since 1986, the maneuver Keen Sword , in Japanese mostly only Nichibei Kyōdō Tōgō Enshū ( 日 米 共同 統 合 演習 , German for "Joint Japanese-American maneuver for integration") has been carried out every two years in order to ensure smooth cooperation between American people in the event of a defense and to train Japanese armed forces. In 2010, foreign observers participated for the first time with the armed forces of the Republic of Korea. The now independent exercise Keen Edge (Japanese 日 米 共同 統 合 指揮所 演習 , Nichibei kyōdō tōgō shikijo enshū ), which takes place in years without Keen Sword , is intended to improve the crisis response ability of the command structures of both countries through computer simulations.

literature

- Morinosuke Kajima: History of Japanese Foreign Relations. Volume 1: From the opening of the country to the Meiji restoration . Wiesbaden 1976. ISBN 3-515-02554-5

See also

Web links

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs : Japan-US Relations , December 2011 (English)

- United States Department of State , Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs: US-Japan Relations , in: Background Note: Japan , 23 August 2011 (English)

Supporting documents and comments

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento of the original from October 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ ヘ メ ッ ト 市 . Kushimoto City, Retrieved March 18, 2015 (Japanese).

- ↑ State Department , June 1, 2010: Opinion Poll: 2010 US Image of Japan

- ↑ China tops Japan in US poll on key ties. In: The Japan Times . June 1, 2010, accessed June 1, 2010 .

- ↑ JETRO: Japan's International Trade in Goods 2007 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Outward FDI flow by Country and Region ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. and Inward FDI flow by Country and Region ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ US Census: Top Trading Partners - Total Trade, Exports, Imports 2007

- ^ Top Ten Countries with which the US has a Trade Deficit

- ↑ Chapter 4: National Defense, Peace Movements and Peace Education in Miki Y. Ishida: Toward Peace: War Responsibility, Postwar Compensation, and Peace Movements and Education in Japan. iUniverse 2005. ISBN 0-595-35063-1

- ↑ Website of 13 AF: Keen Sword ( Memento of the original from December 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ministry of Defense : Nichibei Kyōdō Tōgō Enshū Heisei 22 (2010) ( Memento of the original of March 2, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ USFJ Public Affairs Office, January 15, 2010: Bilateral exercise Keen Edge 10 set to begin ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ground Self Defense Forces: Keen Edge

- Japan in the Library of Congress (English)

- Japan at the Department of State (English)