The Chinese (Glauser)

The Chinese is the fourth Wachtmeister Studer novel by the Swiss author Friedrich Glauser . In this crime thriller, mainly written in 1937, Studer investigates mainly in a poor institution and a horticultural school. A special feature in the genesis of the novel is the fact that the original typescript was stolen shortly before the competition deadline for the Swiss Writers' Association . Within just ten days, Glauser then reconstructed the story and achieved 1st place with the Chinese .

Beginning of the novel

Studer turned off the gas, got off his motorcycle and was amazed at the sudden silence that fell on him from all sides. Walls emerged from the fog, which was felty and yellow and fat like unwashed wool, and the red tiles of a house roof shone. Then a ray of sun stabbed through the haze and hit a round shield: It glowed like gold - no, it wasn't gold, but some other, much less noble metal - two eyes, a nose, and a mouth were drawn on the plate; stiff strands of hair ran from its edge. An inscription dangled under this sign: Economy to the sun; Well-worn stone stairs led to a door, in the frame of which stood an ancient man who looked familiar to the sergeant.

content

Starting position

On a June evening, Sergeant Studer had to make a stop on his motorcycle in the hamlet of Pfründisberg to fill up with petrol. In the process, he met James Fahrni, a globetrotter who returned to his homeland in Bern at the end of his days . The stranger, whom Studer secretly dubbed “Chinese” because of his appearance, predicts that he will be killed within the next few months. Fahrni also seems to know the perpetrators in question and inconspicuously introduces them to the sergeant in the «Sonne» inn: Vinzenz Hungerlott, director of the poor institution, Ernst Sack-Amherd, director of the horticultural school and Rudolf Brönnimann, the innkeeper. Studer does not take the fears of the "Chinese" seriously and leaves Pfründisberg again after refueling his motorcycle. Exactly four months later the sergeant has to go back to Pfründisberg. The body of James Fahrni was discovered in the cemetery: The dead man was shot through the heart, a gun beside him, on the grave of the recently deceased wife of Vinzenz Hungerlott. Since the dead man's clothes have no bullet holes, Studer rules out suicide and begins an investigation.

detection

Apart from two farms, Pfründisberg consists only of the «Sonne» inn, a poor institution and a horticultural school. Studer quickly realizes that the solution to the case must be closely linked to the three “atmospheres”, as he calls the institutions for himself. On the first day, the investigator met James Fahrni's nephew, among others: Ludwig Fahrni, an illegitimate hiring boy who was very fond of the murdered man. The sergeant unceremoniously appoints the boy as his assistant and moves into the former room of the "Chinese" with him. Then Studer sets out to get to know the perpetrators in question in the three “atmospheres”. First he visits Vinzenz Hungerlott in the poor house and begins to doubt whether the recently deceased wife of the poor house father, Anna Hungerlott, actually died of an intestinal flu. The sergeant's suspicions are reinforced when he witnesses a rooster die in front of his eyes the following day after the animal has pecked at the dead clothes. An analysis by the coroner shows arsenic proportions . However, this chemical is also used in the horticultural school for pest control. More people are now in the focus of the suspects: For example, the horticultural teacher Paul Wottli, along with Vinzenz Hungerlott and James Fahrni's sister, would inherit a considerable amount of the deceased. At the end of the second day, another dead person is found: Ludwig Fahrni's brother is lying in the greenhouse of the horticultural school, poisoned by hydrogen cyanide . Although the key is inside and it looks like a suicide again, it is clear to Studer that it is another murder. Notary Münch, who is also in Pfründisberg because of the inheritance of the “Chinese”, finally explains to Studer about James Fahrni's will, and the sergeant suddenly realizes who was behind the murders.

resolution

On the fourth and last day of the investigation, Studer wants to find the real culprit. While a delegation of authorities and politicians is visiting the poor house, it turns out that the sergeant and notary Münch put their lives in danger due to the pending investigation of the case. But Studer has taken precautions: through the intervention of Corporal Murmann, Corporal Reinhard and the unexpected appearance of a witness, the perpetrators are exposed.

disagreements

In January 1938 Glauser wrote to his long-time pen friend and benefactor Martha Ringier: “A story as complicated and wrong as the fever chart shouldn't happen to me again. I have to simplify my fables, then I can limit myself to a few people and then paint everyone right. ». Long before this point in time, Glauser knew that he had to make his crime novels clearer. However, he always struggled with a logical structure, a plan that the plot had to adhere to. As early as 1936 the journalist and friend Josef Halperin gave him the well-meaning advice regarding the temperature curve : “But there is the trick of the detective novel that all advantages are heavily devalued if it fails to unravel in the end. (...) It [the plot] must open smoothly, otherwise the reader will get angry. " The publicist Friedrich Witz also replied: “There is no convincing justification for the events. [...] And because the end suddenly gives the impression of a bursting soap bubble, the disappointment remains, which I shouldn't expect our readers to do. " In spite of this advice, Glauser again ran into logic holes, contradictions and inconsistencies in the Chinese , which were later also criticized by the Competition Commission: The suit of James Fahrni has no bullet holes; it is not clear why the killers dressed the dead man anew. Why was the address on the wrapping paper in which Ernst Äbi the bloody laundry has packaged with a penknife erased? Glauser constructs a classic locked room mystery in the greenhouse , but does not provide the reader with a convincing explanation as to why the key is inside. Why is Hungerlott trying to poison Studer while he is eating, although nobody knew that the investigator was coming for lunch? Why is nobody taking care of the dead student in the horticultural school? And why in the penultimate chapter does Glauser let Studer recap the whole case on several pages in front of the assembled round table, although the reader already knows all this?

Such discrepancies were closely related to Glauser's way of working, which was always linked to his difficult living conditions . The fact that Glauser's crime novels became so successful was mainly due to the fact that he was a master at describing moods and creating atmosphere. In addition, he succeeded time and again in describing fates succinctly and compassionately, such as the insertion of the chapter "The story of Barbara", which is immaterial for the course of the Chinese . The author Erhard Jöst writes about this: «With haunting milieu studies and gripping descriptions of the socio-political situation, he succeeds in casting the reader under his spell. […] Glauser illuminates the dark spots that are normally deliberately excluded because they disturb the supposed idyll. " And the literary critic Hardy Ruoss comes to the same conclusion when he states that «Glauser's crime novels cannot be reduced to the criminological framework, but rediscovered in him the social critic, the storyteller and human artist, but also the porter of the most dense atmospheres."

Emergence

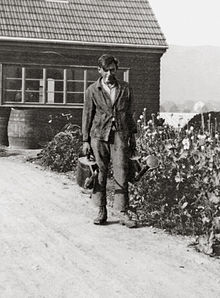

Overall, Glauser worked on the 27 chapters of the Chinese from the summer of 1936 to the summer of 1938 . And similar to the fever curve , this novel was based on an extremely complicated and lengthy genesis. Several factors contributed to this: The difficult working conditions in Angles, the simultaneous work on other texts, the participation of the Chinese in a writers' competition, six changes of location ( the Chinese was created in Angles near Chartres , La Bernerie , Marseille , Collioure , Basel and Nervi ) , the loss of the original typescript and, most recently, a withdrawal of morphine , during which Glauser suffered a fractured skull base before he could start the final revision .

Angles

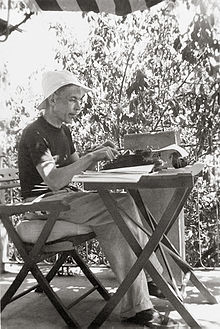

Glauser spent a total of eight years of his life in clinics , six of them in the Münsingen Psychiatry Center alone . When he was released from the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic on May 18, 1936 , Glauser, at the age of 40, finally seemed to have the freedom he had longed for. With his partner Berthe Bendel , whom he had met as a nurse in Münsingen, Glauser wanted to run a small farm in the hamlet of Angles near Chartres and write at the same time. As a condition for this, he had to submit his written declaration of incapacity to marry to the guardianship authorities on April 21 , including the obligation to voluntarily return to the hospital in the event of a relapse into drug addiction. On June 1, 1936, the couple finally reached Chartres. From there they came to the hamlet of Angles (municipality of Le Gué-de-Longroi ), about 15 kilometers to the east, where they stayed until February 1937.

The dream of freedom and independence gave way to various adverse circumstances over the coming months. This began as soon as they arrived at the "estate" which they had leased from the Swiss banker Ernst Jucker (who worked in Paris) . The dilapidated house and the surrounding piece of land were in an absolutely desolate condition; living was hard to think of. On June 18, Glauser wrote to his guardian Robert Schneider in this regard : “Dear Doctor, I would have given you notice of myself earlier, but a nasty tooth ulcer, which bothered me very much, only allowed me to do the most necessary gardening work. The dilapidation in which we found the Gütchen far exceeded all my expectations. There was nothing there. Mr. Jucker adored us a bed (i.e. a spring mattress with a mattress), nothing else. We had to buy everything else. It didn't even have garden tools. " For the next several months, the couple tried to make a living through a combination of self-sufficiency and literary work. Glauser wrote various features articles for Swiss newspapers and magazines. A few texts were written below that describe everyday life in the hamlet of Angles, its residents and peculiarities: a chicken farm (1936), school festival (1936), village festival (1936) or neighbors (1937).

On July 2, 1936, the Swiss Writers 'Association (SSV) and the Swiss Newspaper Publishers' Association announced a competition. The topic was freely selectable, but should be suitable for printing in a Swiss newspaper. The only condition for participation was membership of the Swiss Writers ' Association. Glauser was not a member out of conviction. Just seven weeks ago he wrote to Martha Ringier about this: “Yeah, you're not asking me to join the club? A writers' association is like a Protestant church ; eight horses don't bring me in, even if my dearest friend preaches in it. ». Nevertheless, Glauser began to play with the idea of participating in a competition; he already had an idea in what form. On August 16 he wrote to Friedrich Witz: “I've started a new Studer novel, which I think will be better than the 'fever curve'. [...] It will be called 'The Chinese'. " As of August 21, the expression "competitive novel" appeared in his correspondence for the first time. At the beginning of September, despite internal resistance, Glauser applied for membership in the Swiss Writers' Association . At the end of the month he wrote to Robert Schneider: “Please send me Witzen's letter (the one from the 'ZI') and the 'Hühnerhof' too. The conditions for the competition are on the back. Incidentally, the novel will be set in a poor house, in a horticultural school and in a pub, it will be called “The Chinese” and my friend Studer will call it: “The story of the three atmospheres”. Yes." Glauser found out that he had to deliver a 25-page work sample plus a work plan. On the basis of this, the jury would decide on the final approval. For the first murder in the planned novel, Glauser made use of a scene from the story A World End from 1933. Studer appeared there briefly: “In the village of Steffigen on January 25, 1932, the corpse of an older, well-dressed gentleman was found in the cemetery found in the village. The judicial commission, consisting of examining magistrate Jutzeler, his clerk Montandon and police sergeant Studer, ordered the body to be transported to the morgue. [...] The cause of death was determined to be a shot in the heart. Examining magistrate Jutzeler is said to have immediately stated that this was apparently a suicide, although Dr. Sieber reproached him that this was an impossibility: the clothes of the person shot were not only intact, but the shirt, gilet, skirt and coat had been buttoned by someone else's hand, because it was not to be assumed that a man who had been shot in the heart would still be able to keep his clothes to put in order. "

At the end of September, Glauser received the notification that Morgarten-Verlag would print Die Fieberkurve as a book if he revised the novel again. So it came about that, in addition to all the other work, The Fever Curve moved back into focus. Once again, Glauser had to deal with inconsistencies and gaps in logic in a novel that he had long since finished. In order to avoid such hated reworking, he restricted the number of characters and locations in the new Studer novel from the start. This recipe had already proven itself in his last novel Matto reigns . In the case of the Chinese , Glauser tightened the radius: three buildings, a few main characters.

In October Glauser was accepted into the SSV and was thus able to submit his work sample with the work plan for the competition by the end of 1936. What caused Glauser a headache around the turn of the year was the fact that Hugo Marti was also a feature editor on the jury, who had to hear the Bernese government about the Matto ruling scandal . The fears, however, remained unfounded: of the total of 22 submitted contributions, five remained at the end of February 1937, including Glauser's synopsis on the Chinese . The four competitors were: Jakob Bührer , Emil Schibli, Wolf Schwertebach and Kurt Guggenheim (the latter had to do with his work again after Glauser's death: he wrote the dialogues for the adaptation of Wachtmeister Studer for the Praesens film ). All five authors received a bonus of 800 Swiss francs and were supposed to finish the work they had started by the end of 1937.

In the meantime, however, life in Angles became increasingly difficult for Glauser and Berthe: Living in a dilapidated house, financial worries and the climate drained the two of them. In addition, Glauser couldn't get out of being ill. Several animals that Berthe and Glauser had raised since June 1936 also died inexplicably at this time. Glauser canceled the lease and drove with Berthe to the seaside in La Bernerie. On March 18, he wrote to Martha Ringier from there: “It is wonderful that you can work here again: You are a completely different person than in Angles. One day I would have broken myself there. [...] We have been singing and whistling again for a long time. You'll laugh at me - but I think the house in Angles was bewitched. There are such things. [...] There is someone living in the house who would like to be alone and who is sick of all inmates with illnesses. "

La Bernerie

At the beginning of March 1937, the company moved to La Bernerie-en-Retz in Brittany . Glauser and Berthe rented a holiday bungalow, stayed there until December of the same year, and during this time repeatedly invited friends and acquaintances over. At Gotthard Schuh Glauser wrote on May 10: "It's happened to me long enough bad, why should I not now benefit a little if <just around the corner there is a little sunshine for me>? And if it's even a little, I paid it, the 'sunshine'. " In the new atmosphere Glauser became very productive, so that this is where most of the Chinese originated. In between, however, he always pushed other works, such as the fifth and final Studer novel Die Speiche (Krock & Co.), which was ordered as a serial by the Swiss Observer . And there was still the tiresome revision of the temperature chart , which Glauser found difficult. Under the increasing pressure, he wrote to Josef Halperin in the summer, plagued by doubts: “At the moment I have the impression again that everything is on the brink, the path to writing detective novels seems to be going nowhere. I want to go somewhere, as far away from Europe as possible, and I have a vague idea of a volunteer nurse. If you know anything about this, write to me. Indochina or India - you will still be able to use one somewhere. Because just being a writer - that is not possible in the long run. You lose all contact with reality. " “Studer” seemed to be increasingly a burden for Glauser, as evidenced by a letter from the same year that he wrote to a reader of his novels: “Of course, we, writers, are always happy when people give us compliments - and that's why we are happy I also say that you like the 'stud'. I feel a little like the sorcerer's apprentice , you know: the man who brings the broom to life with the sayings and then couldn't get rid of it. I brought the 'Studer' to life - and I should now, for the devil, write 'Studer novels' and would much rather write something completely different. "

Meanwhile, the deadline for the Chinese was getting closer; there were only ten weeks left. Glauser went back to work and wrote to Martha Ringier on October 18: «I've started again - on the competition novel, and I'm really looking forward to continuing to write it. For the time being I have the whole submitted beginning bypassed and now we want to see how it goes on. " In between, Glauser traveled back to Switzerland: In autumn he was asked whether he wanted to take part in the radio series “Lands and Peoples” with a short text. Glauser accepted, decided on the autobiographical story Kif (1937) and came to the radio company Basel studio on November 18 to record the text. The original recording of this story is the only sound document that Glauser has made. It was no longer broadcast during his lifetime.

By December, The Chinese was practically over; the only thing missing was the end. However, another move was imminent: after Glauser and Berthe had given notice of their apartment, they wanted to travel to Marseille in order to cross over to Tunis . The last letter from La Bernerie, dated December 19, reported to Martha Ringier: “I have to finish my novel on the way - my brain is frozen here. [...] Why do I always fail to draw conclusions? Heaven knows. Hopefully he won't be a mistake for me with the newspaper novel. So far I'm not entirely dissatisfied - and neither is Berthe. In any case, it will be very different from the novels my competitors will send in. " When the two reached Marseille, it became apparent that the plan with Tunis could not be implemented due to pass problems. They moved into a room in the “Hôtel de la Poste”, where Glauser took turns looking after the sick Berthe and most likely wrote the end of the Chinese . After Christmas they decided to continue their journey to Collioure. In a letter (which was never sent) to Otto Kleiber on December 27, 1937, Glauser wrote: “Dear Doctor Kleiber, send you a copy of the competition novel by the same post - and not to make money any faster, but to do so to be sure that not all copies are lost. " [Kleiber, head of the features section of the National Zeitung , had the right to the first edition of the Chinese ].

Glauser had probably planned to make final corrections to the Chinese on the train to Collioure before he could post the Chinese typescript mentioned in the letter at a post office so that Kleiber would have it shortly after the New Year. That didn't happen because the entire competition novel was stolen.

Loss of typescript

On December 28, 1937, the train from Marseille to Collioure was overcrowded with French troops who were on their way to the border as a result of the Spanish Civil War . According to Glauser, he and Berthe fell asleep in their train compartment. When they woke up at Sète station , the folder with the typescript, the plans and all the notes had disappeared. On January 1, 1938, Glauser wrote to Martha Ringier from Collioure: “Probably some soldiers thought that they found espionage material in the folder because they saw us reading it. There are always stupid people in this world. " Also on that day he reported to his guardian Robert Schneider: “I lost the three copies of my competition novel including my correspondence […] on the journey between Montpellier and Sète (rather, it was stolen from us). Despite telegraphing and writing and telephoning, the folder did not come out, and you can perhaps imagine what mood I am in. You are right to argue that I should have finished the novel in the Bernerie - but I couldn't find the last ten pages, that is to say the final punch line. And without a final punchline, a novel is like rabbit pepper that one has forgotten to pickle - excuse the culinary comparison. I have to Dr. Naef and all the other gentlemen wrote - they were very friendly and gave me a month's deadline. " After the competition jury was postponed, Glauser began, under enormous pressure and with the help of Opium , to rewrite the Chinese in Collioure. However, he was afraid that the prescriptions he got from various doctors would attract the attention of the French authorities and so he and Berthe fled back to Switzerland.

Much has been speculated about the loss of Glauser's original typescript. In the course of time, doubts about the theft theory repeatedly surfaced. The literary scholar and Glauser connoisseur Bernhard Echte explains one reason for a possible lie : “Thus, the assumption that Glauser turned an insignificant loss into a comprehensive one when he noticed that he had the deadline of 31.12. would not be able to keep. "

Completely new version in Basel

The “ Odyssey ” in the history of the origin of the Chinese reached a new high point with the flight from Collioure to Basel . On January 8, Glauser and Berthe found accommodation with Martha Ringier and the help they needed to tackle the complete revision of the Chinese . All of the work took place in a specially rented room next to Ringier's apartment. In the ten days that followed, Glauser dictated the entire novel to Berthe Bendel and Martha Ringier from bed. Handwritten corrections to the typescript can be found by Glauser and both women. In a letter to Georg Gross a month later, Glauser described the work on the new version as follows: “In Basel I managed to dictate the novel, which had to be delivered by a certain date, within ten days, which was eight hours of work Dictating meant three hours a day of correcting. Then I finished it, the novel, and was done afterwards. " And Martha Ringier remembered: “It was an agonizing time, it weighed heavily on Glauser. His features were tense, his forehead mostly furrowed. He was easily irritated and sensitive. We two women tried to put every stone out of his way and often just asked ourselves with our looks: What will the result of this overexertion be? " The consequences of this ordeal became apparent shortly afterwards: on January 28th, the three newly written competition copies of the Chinese were presented to the SSV , but Glauser suffered a collapse.

Friedmatt Clinic and 1st prize

The fact that Glauser used drugs when writing was nothing new. And so it was almost foreseeable that during the literary show of strength of the Chinese , he would fall back again into morphine and opium consumption. There were also sleeping problems and sleeping pills. After the collapse, Glauser was admitted to the Friedmatt Psychiatric Clinic in Basel from February 4 to March 17 . Another momentous incident occurred there on February 15: Glauser fainted during insulin shock therapy and fell with the back of his head on the bare tiles in the bathroom. The consequences were a fracture of the base of the skull and severe traumatic brain injury . The aftermath of this accident affected Glauser until his death ten months later.

On February 23, Glauser's efforts and sacrifices were rewarded: With his fourth Wachtmeister Studer novel, he won first prize in the competition of the Swiss Writers' Association and won the prize money of 1,000 Swiss francs. However, the jury attached one condition to the victory: Glauser should revise the Chinese .

Post-processing in Nervi

Nervi near Genoa was Glauser's last place of residence from June to December 1938. During that six months he wrote several pages a day on various texts and projects. Among other things, he also worked on the Studer Roman fragments , one of which was even supposed to be set in Angles. In addition, Der Chinese was still waiting for its revision, which, once more, was torture for Glauser. Most of the jury's requests for revisions were not carried out and so Otto Kleiber wrote to Glauser on July 13th: «I only got around to reading your new version yesterday […]. Based on your letter, in which you write that 'very little was left of the first draft', I believed that a revision according to the intentions and the like would really be necessary. The jury's suggestions. Now I have seen that a very intensive reworking actually took place, but essentially only in terms of the stylistic, while in the appendix u. the psychological constellation everything stayed the same. But it was precisely in this direction that the jury's wishes [elimination of improbabilities and exhausted motifs] ». However, it was too late for a further revision, as Der Chinese was already ducked on July 26th.

Four days after Kleiber's letter, Glauser wrote to his guardian Schneider in this regard: “I was happy that I was finally able to rework the award-winning novel and sent it to Switzerland. It seems that his printing will begin next week in the "Nat-Ztg." Strange - but with this novel - despite the first prize it won - I was just unlucky. First it was stolen from me, then I dictated it down in ten days and was then able to go to Friedmatt. I fell on my head just before the jury made its decision, and I was able to work on that for almost half a year. Really, a couple of times I was scared - I thought I wouldn't be able to write at all. " On July 23, in a letter to Alfred Graber , Glauser titled the Chinese as a “ trash novel ”: “A few things got in my way that prevented me from answering earlier. At first I got here pretty badly, then I had to rewrite the award-winning trash novel (or, if you think that's more decent: the newspaper novel) - and that was a nasty thing. "

The last few months in Nervi seemed to have been very stressful for Glauser and Berthe, as there was an increasing lack of money and writing jobs. A letter from Glauser from October 4th to Max Ras from the Swiss observer also testifies to this : “We have run out of black horses, our marriage is just around the corner, we should live, and worries make me break up. [...] Apart from you, I have no one else I can turn to. [...] I don't know what to do anymore. My God, I think you know me enough to know that I am not the kind of person who likes to curry favor with others and whine in order to get something. You know my life has not always been rosy. It's just that I'm tired now and don't know whether it's worth going on. " On the eve of his wedding to Berthe Bendel, Glauser collapsed unexpectedly and died at the age of 42 in the first hours of December 8, 1938.

Biographical background

Locations

In Der Chinese, Glauser limited himself to just one village with three building complexes (including the cemetery). One of them was a horticultural school, as he had a detailed background in this regard: Glauser had already worked as an auxiliary gardener from 1926 to 1928; In March 1930 he even entered the cantonal horticultural school in the hamlet of Oschberg in the Emmental and graduated with a diploma in February of the following year.

Oeschberg

In his fourth Studer novel, Glauser redesigned the experience in Oeschberg in detail into a main scene and crime scene. So he changed the real place name of the horticultural school to the fictional Pfründisberg. Glauser used the old people's home on the edge of the forest east of the horticultural school as a model for the poor house; Until 1880 this building was a tavern called "Gasthof zur Sonne". Glauser then adopted the name for the village pub in the crime thriller. In the novel, Gampligen, two kilometers away, is mentioned several times; behind it is the town of Koppigen (also two kilometers away) .

characters

For the Chinese , Glauser borrowed very few figures from his circle of friends. One of them was the teacher Kienli from the Oeschberg Horticultural School; this served as a model for the teacher Paul Wottli. And behind the student name Walter Amstein, Leo Amstein, a fellow patient of Glauser in 1920 in the Burghölzli psychiatric clinic, hid .

Martha Ringier

The chatty and wealthy Basel woman, Ms. Wottli, the mother of the horticultural teacher at Aarbergergasse 25 in Bern, deserves special attention : Glauser describes the older woman in the bourgeois, honest and meticulously clean apartment with white hair and a wrinkle-free face, whose flow of speech in the Basel dialect is nothing could insulate. Studer's head starts to growl after a short time. This figure has some similarities with Martha Ringier (1874–1967), who lived in St. Alban-Anlage 65 in Basel , was single and from 1935 onwards became Glauser's maternal friend and patron. Ringier understood her life in the service of literature (in 1924 she rented an apartment to Hermann Hesse , where he began his work on the Steppenwolf ) and wrote poems and stories herself. In addition, she worked as an editor for the family magazine Die Garbe , the Swiss Animal Welfare Calendar and was in charge of the Gute Schriften series . In this context and through her relationship with the publishing industry, she repeatedly passed Glauser's texts to various newspapers and magazines. Glauser had already described a figure similar to that of his mother Wottli in the fever curve : Sophie Hornuss, who died of gas poisoning, was a rich, lonely and also greedy woman. The fact that the two portraits of the old and single women were not very advantageous has to do with the fact that the differences between Glauser and Ringier reached their climax when the Chinese in La Bernerie was created, as he still owed her a story and, above all, owed money .

→ Detailed chapter: Glauser and Martha Ringier

A rooster named Hans

Glauser also gave autobiographical space to an animal: “'Hansli!' Called the laundress. The rooster trotted closer, tried to crow, shook itself - and began to peck at the sheets that lay on the floor. […] The little chicken that had pecked around in the dirty laundry and worked on Studer's find with its sharp beak fell over. From below his lid pushed over his eye, Hansli croaked weakly, stretched his claws - and then he was dead. " The literary death of the rooster had a special reason: After Glauser had already portrayed a mule in the fever chart , he now described a rooster in Chinese that had unmistakably played a role in the household of Glauser and Berthe in Angles. In his short text Ein Hühnerhof from 1936, he describes how they found the animal, integrated it into their chicken yard, and then philosophizes about the all too human behavior of the animals: “We picked up an abandoned chick on a Sunday walk. [...] Yes, I named the animal Hans before I knew what gender it was. [...] But Hans is of a simple nature - a proletarian . The intellectual fuss of the ducks gets on his nerves. […] A chicken yard is an instructive matter. It encourages philosophy and humility. " Glauser also comes to the realization that “we have in vain set up the barrier between humans and animals, between humans and animals and plants” (the feature section appeared in the National-Zeitung on August 21, 1936 through the mediation of Martha Ringier).

In the summer of 1936 Glauser also taught Hans tricks; on August 15th he wrote to Martha Ringier: “The weather is fine, today I taught Hans how to dance the tightrope, on the linen rope, he's a little clumsy, but otherwise docile. And if everything goes wrong, I appear in the Küchlin as a chicken dresser - the young Swiss writer, whose name you will have to remember, in a solo act, surrounded by his flock of chickens. If that doesn't work! " There is a photo of Glauser's “Chicken Dressage on the Rope”, which is also included in the publication “Friedrich Glauser. Memories »is printed.

adventures

Since Glauser was unable to make a living from his literary work throughout his life, he repeatedly wanted to be independent through a profession. One profession that he pursued for years and finally completed an annual course was that of gardening.

Gardening

For the first time Glauser worked as a handyman from June 1926 to March 1927 in Liestal at Jakob Heini's nursery. Glauser built this experience into his first Wachtmeister Studer novel (" Baumschule Ellenberger" in Schlumpf Erwin Mord ). In April 1927 he began psychoanalysis with Max Müller , which lasted about a year; During this time he worked in the Jäcky nursery in Münsingen . On April 1, 1928, he took up a position as an auxiliary gardener in Riehen with R. Wackernagel, a son of the historian Rudolf Wackernagel ; At that time he lived with his then girlfriend Beatrix Gutekunst at Güterstrasse 219 in Basel . In September 1928 he moved to the E. Müller commercial nursery in Basel, where he worked until December 1928. In the short story tree nurseries (1934) Glauser first processed his earliest experiences in nurseries in literature.

In March 1930 Glauser entered the cantonal horticultural school in the hamlet of Oeschberg. This was mediated by Max Müller , who had also agreed that Glauser could obtain controlled opium without becoming a criminal. Emil Weibel, a former horticultural teacher, recalled in 1975 the documentary Friedrich Glauser - An Investigation : «Glauser came here in the spring of 1930 as a year-old student. Nothing else was known about him. In the course of time it turned out that he had traveled far around the world. We learned from the director that he was a writer and wrote novels. In the evening off, he wrote, always smoking. Probably so that he had ideas for a crime novel, he needed drugs. " Glauser himself described the Oeschberg year in letters to his friend from the Asconesian days , Bruno Goetz , as a rather painful time. In November 1930 he reported: “After that I'll be back in the horticultural school. I took on the ordeal because I felt it was necessary and I needed some fresh air work in addition to writing. But I have not yet found the right connection between the two. " In the two other letters of February 1932 he wrote: “The society I was with for a year is completely disgusted. Well, only three more weeks, thank God. " And: “I count the days to the end. I've learned something, even if it's not a lot, but so much that I can stay afloat if it's not enough to write. And you starve to death. " In February 1931 Glauser graduated with a diploma. Two months later, Max Müller wrote to Glauser: “In any case, it's very nice that you were able to finish the Oeschberg in spite of everything. [...] I consider this to be an achievement that you would certainly not have been able to achieve in the past, and I congratulate you on your exams afterwards. "

In Chinese , the reader encounters a number of technical terms for the gardening profession. There is talk of "Krauterer" [a professional insult], fertilizer apprenticeship or tree pruning when teacher Wottli lectures: "When you cut a pyramid, you have to make sure that the construction, that the structure of the tree does not suffer." In Glauser's exercise book there is an entry “Fruit culture and fruit processing” with a sketch and description of the pyramid section. Chemicals and poisons such as uspulun as a dressing agent for cyclamen seeds also play a role in the determination; Glauser has also received a booklet on toxins: “Pests and diseases of fruit and vegetable growing”. In the novel, Wottli says to Studer: «I suggested that he run a competition - among my students. Everyone should draw a plan, the best one should be awarded a price of five hundred francs. " Glauser had also borrowed the idea of the competition from reality; on April 27, 1930 he wrote to his first guardian Walter Schiller: “We have to submit a competition every month, which is rewarded with points. […] We already have one behind us and I was third with 26 points and very satisfied. I had tried something new and it was half successful. To be successful, I still lack practice. But drafting a plan is just as interesting as writing a novella , I think. "

Publications

Newspapers

From July 26 to September 13, 1938, Der Chinese was the first edition to appear in the National-Zeitung ; Otto Kleiber, feuilleton boss of the newspaper, had the right to the first edition of the continuing story in 42 episodes. The Thurgauer Zeitung began printing just a week after the National-Zeitung . In total, Der Chinese appeared in sixteen Swiss German daily newspapers.

Book editions

The book edition of the Chinese fared like the novels Gourrama , The Speiche and The Tea of the Three Old Ladies : They all appeared only after Glauser's death. In 1939 Morgarten-Verlag was the first to print the Chinese , in 1957 it appeared in the Sphinx crime series of the Gutenberg Book Guild and in 1970 in the work edition of the Arche Verlag .

"The Chinese" in Chinese

In 1995, Chinese Wen-huei Chu, a Taiwanese award-winning writer, translated Glauser's crime thriller into Chinese. It was thanks to Chu's translation that Georges Simenon's « Maigret » investigated in Taiwan. With Glauser, however, the transfer turned out to be far more difficult. Chu in the news magazine Facts : “What on earth does 'finger off de Röschti' mean? Wen-huei Chu groans at his desk. [...] For expressions like ‹ Bätziwasser › or ‹ Tschugger ›, the Chinese equivalent has to be found first, preferably in the Cantonese or Taiwanese dialect, which then corresponds to Studer's Bern German . But sometimes there is no such equivalent. Then only the description remains. Page after page of the translation, Chu's notebook computer spits out. [...] Friedrich Glauser? Chu also had to transfer the name and write it in writing. But in Chinese there is neither an r nor a rough ch, and every single consonant is paired with a vowel . So the Swiss author is called Fu-li-dö-li-si Gö-lau-sö. "

reception

The Chinese was very successful when it appeared (in the newspapers and as a book edition). For example, the federal government wrote: “It should be noted that the book is not about a real Chinese and therefore does not take place in the Far East, but the 'Chinese' is the nickname for a Swiss abroad who has returned home, whose mysterious death is the core and starting point the fable that is skilfully treated. With the exception of Studer, who has already become dear to us, all figures are made from such down-to-earth material; they act and speak so lively and unaffected that you not only devour the book in extreme tension, but read it carefully a second time in order to be able to enjoy all its psychological, criminalistic and linguistic peculiarities in peace. Can you ask for more from a detective novel? We don't believe. "

filming

In 1979, Der Chinese was filmed in a co-production by Bavaria Film and Swiss Radio and Television under the direction of the film director Kurt Gloor . In the epilogue to Hannes Binder's Knarrende Schuhe , Gloor tells how he discovered Glauser: “I remember how much I read the Glauser stories with great pleasure, back then, twelve years ago, when I was slurping them all down one after the other. I was drunk by the vivid stories, by Glauser's accuracy in detail and by his exact descriptions of moods, situations and characters. He had done it to me, this wonderful narrator, this astute human observer who knows the world of his characters - from his own bitter experience. "

The adaptation of the novel turned out to be more difficult than expected. Gloor said: “I was looking forward to making The Chinese a television film. But I was very disappointed when I received the script from Bavaria Film in Munich. That was no longer a real Glauser, it was more like a dozen thriller. It was gone, the witty-cunning, occasionally bilious-ironic view of Glauser on his staff and their sensitivities, vanities, hopes, longings and stupidities. [...] The scriptwriter had purged the Chinese with German thoroughness. So I got down to it myself, tried to replant the lost Glauser so that the story smells again, of Bätzi water and Brissagos , not just of milk from happy cows. But that was difficult. Because all the artfully intertwined narrative garlands and ivy that make up Glauser's reading pleasure drive a cold sweat on the forehead of a screenwriter who is forced to simplify, cut, omit and disentangle. Glauser, it seemed to me, is the undisputed Swiss champion in hundreds of meters of dramatic traps. Sometimes I wonder if the writer Glauser could have had anything against scriptwriters and filmmakers - in a way, prophylactically. "

Hans Heinz Moser , who appeared in the 1976 film adaptation of "Krock & Co." Slipped into the role of the investigator, played the sergeant again. Moser was forced to oppose the archetype of Studer in Heinrich Gretler's interpretation of the figure in Wachtmeister Studer (1939) and Matto reigns (1946). The Neue Zürcher Zeitung wrote in this regard: “Beyond every questioning whether Glauser really meant his sergeant that way, Gretler was the ideal figure in this role, which met a broad mood among the Swiss people. [...] Moser wanted and could not play this Studer in the socially coherent way screwed down by Gretler - also and especially according to the artistic will of Kurt Gloor [...]. "

Theater adaptation

The Chinese has been performed regularly by amateur theater ensembles over the years. For example, the 75th anniversary of Glauser's death was commemorated by the Swiss crime writer's “Volkstheater Wädenswil ” with the play “Der Chinese”: The premiere was on September 7, 2013, for which Andri Beyeler wrote the stage version and Jürg Schneckenburger directed. In April 2014, the “Theatergesellschaft Willisau ” staged Simon Ledermann's adaptation in the Zeughaus , directed by theater pedagogue Christine Faissler.

Comic

In the mid-1980s, graphic artist and illustrator Hannes Binder was commissioned by Arche Verlag to design the covers for the six-volume paperback edition of Glauser's detective novels. Thereupon Binder read Glauser's books, whereby Der Chinese especially fascinated him. So the idea came up to draw this crime thriller as a comic. Binder then researched the Emmental by photographing landscapes, buildings and details in order to obtain optical specifications for Glauser's Pfründisberg. Apart from a few interruptions, the graphic implementation of the novel took three years. Binder used the scrapboard technique : a cardboard box is covered with a very thin layer of black plaster paint, which is scraped away with a penknife so that a white line is created.

In 1988 the graphic novel Der Chinese was finally published . Binder comments: “The Glauser was not yet available in paperback and that was the first test balloon for me,“ The Chinese ”. That more or less succeeded, it sold very well because there was nothing like it in the German-speaking area, a literature adaptation. " Like Kurt Gloor when he made the film version of the "Chinese", Binder also had similar problems with the implementation: "If you have to leave out too much of it, in the end you only have the framework of a shaky story and you can no longer feel the Glauser." Nevertheless, Binder stuck very closely to the literary model in his implementation: After all the important characters have been introduced, a total of 443 panels follow , which retell Glauser's novel 1: 1. Binder also adopts its chapter headings and introduces brief text introductions to the plot. He works with cinematic means such as long shots, close-ups and sometimes extreme angles. Binder only left out Chapter 9, “The Story of Barbara”, because this episode about the fate of Ludwig Fahrni is not essential for the plot of the crime thriller. To this end, the comic is supplemented by four pictures showing the incident of the typescript loss in Sète .

Looking back in 1990, in the epilogue to “Creaky Shoes”, Binder stated that he was not completely satisfied with the Chinese comic because he was perhaps striving to be too faithful to the work, but had neglected a lot of visual things so that the plot would stand. In his next Glauser comic, "Krock & Co./Die Speiche" (1990), Binder corrected this by making the implementation more visual.

Audio books

- The Chinese. Christoph Merian Verlag, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-85616-308-2 .

Documentaries

- 1975: Felice Antonio Vitali: Concerns Friedrich Glauser - An investigation.

- 2011: Christoph Kühn (Director): Glauser - The eventful life of a great writer. With Berthe Bendel , Max Müller , Martin Borner , Hardy Ruoss , Hansjörg Schneider , Frank Göhre , illustrations by Hannes Binder . DVD . Limmat, Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-85791-701-1 .

literature

- Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser, two volumes, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main / Zurich 1981.

- Volume 1: A biography. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052534 ; NA: 1990, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 .

- Volume 2: A work history. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052683 .

- Bernhard Echte and Manfred Papst (eds.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 .

- Frank Göhre: Contemporary Glauser - A Portrait. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2077-X .

- Hannes Binder: The Chinese (Friedrich Glauser). Crime comic, Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2067-2 .

- Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 .

- Rainer Redies: About Wachtmeister Studer - Biographical Sketches. Edition Hans Erpf, Bern 1993, ISBN 3-905517-60-4 .

- Friedrich Glauser: The Chinese. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-244-8 .

- Heiner Spiess and Peter Edwin Erismann (eds.): Memories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-274-X .

- Hannes Binder: Nüüd Appartigs… - Six drawn stories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-85791-481-5 .

- Martina Wernli: Writing in the margin - “The Bernese cantonal mental institution Waldau” and its narratives (1895–1936). Transcript, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-8376-2878-4 (Dissertation Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule ETH Zurich, No. 20260, 2011, 388 pages).

Web links

- The Chinese in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ART-TV: The "Theatergesellschaft Willisau" with the play Der Chinese

- Friedrich Glauser's estate in the HelveticArchives archive database of the Swiss National Library in Bern

- Friedrich Glauser's estate inventory in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 816.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, pp. 129/130.

- ↑ Erhard Jöst: Souls are fragile - Friedrich Glauser's crime novels illuminate the dark side of Switzerland. In Die Horen - magazine for literature, art and criticism. Wirtschaftsverlag, Bremerhaven 1987, p. 75.

- ↑ Hardy Ruoss: Do not scoff at detective novels - reasons and backgrounds of Friedrich Glauser's stories. In Die Horen - magazine for literature, art and criticism. Wirtschaftsverlag, Bremerhaven 1987, p. 61.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 315.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 192.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 164.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 192.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 4: Broken glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 9.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 296.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 343/344.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 373.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , pp. 335/341.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 572.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 603.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 624.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 803.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 774.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 4: Broken glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 90.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 799/800.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 807.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 157.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 813.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 808.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 833.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 158.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 844/845.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 851.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 854.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , pp. 874/875.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The Chinese. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-244-8 , pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 192.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , pp. 172-174.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 341.

- ↑ Peter Erismann, Heiner Spiess (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser. Memories. Limmat, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-274-X , p. 81.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 21.

- ^ Documentary about Friedrich Glauser - An investigation by Felice Antonio Vitali, 1975

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 156, 159/169.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 342.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The Chinese. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-244-8 , p. 139.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 301.

- ↑ Glauser in Chinese - Friedrich becomes Fu-li-dö-li-si. In: Facts. April 6, 1995.

- ↑ Hannes Binder: Nüüd Appartigs… - Six drawn stories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-85791-481-5 , p. 226

- ↑ Look at the screen. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. January 19, 1994.

- ↑ Sergeant Studer investigates in the cold house. In: Zürichsee Zeitung. 5th September 2013.

- ^ A tricky case for Sergeant Studer. In: Willisauer Bote. March 18, 2014.

- ↑ The black painter with the scrapboard technique. Hannes Binder in conversation with Ute Wegmann , Deutschlandfunk 2016

- ↑ Hannes Binder: Nüüd Appartigs… - Six drawn stories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-85791-481-5 , p. 226

- ↑ Creaky shoes (Friedrich Glauser). Picture thriller. Afterword by Kurt Gloor , Arche, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-7160-2155-5

- ↑ Publishing information