Historical Exodus Research

The Historical Exodus research deals with the question of how the exodus from Egypt , as described in particular in the Book of Exodus of (chapters 1-15) Hebrew Bible is portrayed on historical facts is due.

The Exodus narrative depicts mythical events and is enriched with many purely narrative elements, which is why it is by no means pure historiography . Also there was certainly no exodus from Egypt to the extent described. Nor does the narrative give a clear indication of a specific time in Egyptian history . It is therefore an almost inconceivable event for historians .

The extent to which “biblical” Israel corresponds to a historical Israel of the pre-exilic period (before 597 BC) is difficult to answer in view of the problematic source situation and is extremely controversial in research. On the one hand there are researchers who defend the historicity of Israel's excerpts from Egypt, at least in its basic features, on the other hand there are those who more or less radically deny the historicity of the Exodus and relegate the described events to the area of myth formation in later epochs.

Various researchers assume that the Exodus narrative is not tailored to a specific historical situation, but grew out of a long history of Israeli experience. The resulting openness of the narrative should enable the Israelite descendants to be able to equate “the pharaoh” with the currently threatening potentates again and again in changing political situations, be it the Egyptian pharaohs such as Ramses II , Merenptah or Ramses III. , their own kings like Solomon and Ahab , or the Assyrian and Babylonian foreign rulers like Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar II.

Jan Assmann shaped the memory-historical approach , which no longer asks “how it actually was”, but rather how it was remembered. The Exodus story is likely to have been linked to various historical memories, for example of the Hyksos , of the Egyptian colonial rule in Canaan during the late Bronze Age , of the Apiru group and of migrations during the Sea Peoples' era.

The question of historicity

The Book of Exodus is by no means a matter of simple historiography. The Exodus from Egypt deals with monstrous and mythological events such as the division of a sea, the ten biblical plagues and enormous revelations in the desert of the Sinai Peninsula . The Exodus narrative gives no clear indication of a specific time in Egyptian history. The fact that no Egyptian king is named by name contributes to the historical vagueness. The Egyptian sources also provide no direct reference to such an event. According to biblical information, there were around 600,000 men in the allegiance, which (with women and children) would result in a population of around 2 million people. Since the population of Egypt in the New Kingdom was an estimated 3 to 4.5 million people, an exodus of this size would have been a disastrous event. But there is no evidence of such a traumatic event for the New Kingdom. On the other hand, there was no reason for the later history of Israel to look for the type of brutal foreign ruler in Egypt of all places. Thus, for Donald B. Redford, the Exodus remains one of the most elusive events for historians of all the great events in Israeli history .

The extent to which “biblical” Israel corresponds to a historical Israel of the pre-exilic period is difficult to answer in view of the problematic sources and is extremely controversial in research. On the one hand there are researchers who defend the historicity of at least the main features of Israel's exodus from Egypt, on the other there are those who more or less radically deny the historicity of the Exodus and refer the events described to the myths of later epochs. In between there are numerous views that suggest some core of historicity, even if they differ widely.

So is James K. Hoff Meier estimates that "Israel" was living for some time in Egypt and "outside" of Canaan invaded. Werner H. Schmidt sees it similarly : “According to all historical insight, however, only one group stayed in Egypt, which later became part of the people of Israel - probably more precisely in the northern Reich. In such a restricted way, the tradition contains a reliable core. ”In contrast, Christian Frevel writes :“ The Exodus - as the Bible describes it - is not historical. [...] Since none of the biblical evidence is contemporary and their source value remains limited, the historical evidence of an exodus is hopeless. ”Donald B. Redford points out that the figure of Moses and the events around him are not historical Withstand the test. That is why Moses was a mythological founding figure for the Hebrews, comparable to Arthur for Britain or Aeneas for Rome .

Scientists who follow a “traditional” view largely assume that the biblical material reflects the situation in the Late Bronze Age (13th century BC). This is the period calculated according to the logic of biblical chronology. These scientists face two main problems:

- Until about 800 BC There was no significant written activity in Israel. For a period of more than four centuries they must therefore assume an oral transmission of the narrative, without it being infiltrated by realities from the period in between.

- There is not a single piece of evidence to support an origin of the tradition in the late Bronze Age that cannot be understood against the background of another, later epoch.

Supporters of the “critical” camp assume that the text describes the reality that prevailed at the time the text was written. This would correspond to the late monarchical to post-exilic period. The main difficulty these researchers face is the strong tradition of both the Exodus and the desert wandering in the writings of the northern prophets of the 8th century BC. Chr. Israel Finkelstein draws attention to the following points:

- This tradition had already existed in northern Israel in the 8th century BC. An important status.

- It already contains an “inner” literary history.

- Originally it was independent of - and earlier than - the stories of the patriarchs.

- The two blocs - Patriarch and Exodus - were joined at a relatively late date.

- In its current form, the narrative represents priestly (or even late-priestly and / or post-priestly) compilations.

In 2015, Israel Finkelstein examined toponyms of the desert migration tradition from an archaeological point of view and came to the following conclusion: The Exodus migration tradition is the final product of many centuries of accumulation and growth, first verbally and then in writing, with a complex history of editorial departments in the light of changing political and historical realities.

For Jan Assmann , questions about historical reality lead nowhere: “The biblical narratives are contradicting themselves and extra-biblical sources and traces could hardly be found. The 'historical Moses' has disintegrated into nothing and an excerpt from the stories cannot be reconstructed. ”That is why he uses the method of memory history, which no longer asks“ how it actually was ”, but rather how it remembers became, "that is, when, why, by whom, for whom, in what forms this past became important." In the opposite direction, one can also ask what well-known events could have been linked to the traditions. "What is of particular interest here are the unquestionably verifiable, centuries-old contacts between the Egyptians and their Western Semitic neighbors (let's call them Canaanites, residents of Palestine, Syrians or Hebrews), which are not only found in the archaeological remains, but also in the oral and literary tradition, that is, in the cultural memory of the peoples and tribes concerned, must have left traces. "

The word "Israel" in extra-biblical sources

"Israel" as the name of a person on a list of warriors from Ugarit

In 1954/1955, during excavations in Ugarit , a list of warriors was discovered which named a person named "Israel" (jšril) in second place. The cuneiform tablet lists the names of chariots who belonged to the Mitanni and formed one of the leading strata in the Ugaritic army. It was found in the kiln of a palace courtyard. Since it was probably still in the oven when it was destroyed, it is believed to have been dated to the end of the 13th century BC. To date - around the same time as the Merenptah stele.

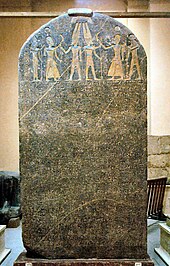

The Merenptah stele

The text of the Merenptah stele , which is also known as the Israel stele, is available in two versions: on the one hand as a detailed inscription in Karnak and on the other hand in a shorter version on an originally free-standing stele in Thebes-West . The text is a song of victory for the aforementioned successful military enterprise of Merenptah in his 5th year of reign (1208 BC). It contains the so-called "Israel punch": "Israel lies fallow and has no seed" or, according to different proposals: "Israel lies fallow and has no descendants (any more)" in a list that includes seven other towns in the Syro-Palestinian region Space calls.

In contrast to the other geographical names mentioned, the word "Israel" is not written here with the determinative for a place or country, but with that of a group of people or people. Thus, at the end of the 13th century, Israel was not understood as a state, but as a name for a group of people. The mention of a tribe of Israel is the oldest and only unambiguous non-biblical evidence of the existence of the name Israel in Ramessid times . It should be up to the 9th century BC. It took until the first time a state named House Omri was recorded in Assyrian inscriptions and the Mesha stele as equating with the name Israel. The question of historical similarities with the nomadic people of Israel described in the Merenptah stele and the later state has not yet been clarified. The other places mentioned, however, are partly to be assigned to some cities in historical Israel , at least Gezer and the Philistine city of Ashkelon . For Jenoam several come into consideration, including a place on the border of the tribe of Ephraim and Manasseh (see Twelve Tribes of Israel ) and Janoaḥ east of Tire ; Jokne'am , which still exists today, cannot be ruled out either.

Presumed mention on a fragment in Berlin

Manfred Görg was the first to notice in 2001 that the relief with inventory number 21687 in the possession of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin contains a hieroglyphic inscription with a name that could be read as an archaic form of "Israel". So one could understand j-š3-ir as "I-schra-il". The granite block is a typical representation of three prisoners of war with a list of place names, two of which are clearly legible: "Canaan" and "Ashkelon". Görg dated the fragment to the 19th dynasty - perhaps the time of Ramses II - mainly because the names are very similar to those on the Merenptah stele and because this dating is supported by iconographic features.

James K. Hoffmeier speaks out against an identification with "Israel" for linguistic reasons: If it were a mention of the biblical people, an "s" would be expected - and not a "š" (pronunciation: "sch") . Against this argument, Görg, the biblical archaeologist Peter van der Veen , the Egyptologist Christoffer Theis and colleagues argue that, firstly, the rules and habits of transcription kept changing, and secondly, examples that have been handed down have shown that the pronunciation with “sch” is widespread in some dialects thirdly, one does not know how the Egyptian scribe had found out about the name, since he might have known it from an Akkadian text that used other transcription methods, and fourthly, one does not know how old the Egyptian one was Was a scribe, but he could have been so old that he came from a time (early 18th dynasty) when transcription with "sch" was still common practice; just because “Israel” was written with an “s” on the Merenptah stele, this does not mean that this has to apply to all other mentions as well. In addition, Görg, van der Veen and colleagues cite chronological-historical-contextual plausibility arguments for the thesis represented. It is received positively by Bible archaeologists and Egyptologists such as Bryant G. Wood and Stefan Jakob Wimmer .

Location information

The most important basis for the historical localization are the two cities of Ramses and Pitom named in Ex 1,11 : “And bondmasters were placed over them, who were supposed to oppress them with forced labor. And they built the cities of Pitom and Ramses for Pharaoh as storage cities. "

Ramses

The Old Testament place name "Ramses" (in Ex 1,11 raˁamses, written in 12,37 raˁmˁses) is mostly equated with Pi-Ramesse , the seat of the Ramesside Pharaohs. For example, Ramses is a short form of Pi-Ramesse, since the “Pi-” or “Per-” could be left out in ancient Egyptian under certain conditions. However, some researchers point out that many other place names were constructed with the name Ramses, which is why the identification is not clear. Since several Bible passages indicate the living area of the "Children of Israel" near the palace and an administrative center, according to Manfred Bietak only the famous Pi-Ramesse residence can be meant.

Older research identified the biblical Ramses with the location Tanis / Ṣān al-Ḥaǧar, which in ancient Israel had been around since the 8th century BC at the latest. Was known under the name Zoan ( soˁan ) (Isa 19:11, 13; 30,4; Ez 30:14). In Ps 78:12, 43 even the exodus events are localized in the “realms of Zoan”. However, this is due to the fact that the archaeological remains from the Ramesside period were built secondarily in Tanis / Zoan. Nevertheless, the Old Testament authors could change the situation from the middle of the 1st millennium BC onwards. Describe when Tanis / Zoan was identified in Egypt with the delta residence of the Ramessids. The designation as “storage city” could also be an indication that there is an old memory here, because this category is rather unsuitable for a metropolis like Pi-Ramesse.

Pithome

Pithom is the Hebrew form of the ancient Egyptian Pi-Tum (also Pi-Atum or Per-Atum, from pr-Jtm - "House of Atum "). The place was definitely in Wadi Tumilat , a 50 km long valley in the eastern Nile Delta . It is disputed which archaeological site the name is associated with. There are Tell el-Maschuta or Tell er-Retaba in question.

The place name is first mentioned in the Anastasi VI papyrus, which dates to the time of Merenptah . It says that Shasu Bedouins came to the lakes of Pi-Atum, in the Tjeku region, to feed their herds. Tjeku probably originally referred to the entire region of Wadi Tumilat. But it is also connected to the Tell el-Maschuta site.

In Tell el-Maschutta, a statue and the so-called pithom stele were also found, which refer to Pi-Atum. However, this site was not re-established until the 7th century. Before that, however, there was a temple in Tell er-Retaba, 15 km away, for the cult of "Atum, Lord of Tjeku". Karl Jansen-Winkeln therefore assumes that both Tell er-Retaba and the successor settlement Tell el-Maschuta were named Tjeku (in the narrower sense) and Per-Atum (Pithom), although the latter was only for Tell el-Maschuta is explicitly assigned. Donald B. Redford, on the other hand, advocates a clear identification of Pithom with Tell el-Maschuta. On this basis, the mention of the city in the Bible should be an anachronism . Manfred Bietak, on the other hand, clearly identified the place name Pithom with Tell er-Retaba: The identification with Tell el-Maschuta could at best be interpreted as the relocation of the temple of Pi-Atum from Tell er-Retaba to Tell el-Maschuta.

However, the designation storage city does not seem to fit the function of the city of Pi-Atum: "Storage cities" are stations that were created with supplies to supply the army and with garrisons to secure the major campaign routes.

Goschen

The Israelites inhabited (according to Ex 8,18 and 9,26) in Egypt a "land of Goshen". According to Gen 45,10 and 46,29, this area is to be thought of in the vicinity of Joseph's whereabouts. It could mean one of the royal cities of Lower Egypt, either Pi-Ramesse or Bubastis . So the Septuagint suggests a localization in the eastern Nile Delta, because in some places this Goschen gives as "Gosem Arabia (s)" (Gen 45,10; 46,34) or "Heroonpolis" (Gen 46,28 f). "Arabia" refers to the 20th district in Lower Egypt on the eastern edge of the Nile Delta. Heroonpolis is the Greek name of Pithom (see also other names of Pithom ).

Due to the localization in the eastern Nile Delta, some researchers advocated equating Goschen with the Egyptian name gsm (pronounced: "gesem"). This is documented, among other things, on an inscription from the Ptolemaic period, which comes from Saft el-Henna , which is about 12 km southwest of Pi-Ramesse / Qantir. The reading and philological connection to Goshen is, however, controversial.

In the book of Joshua (Jos 10:41; 11:16) the "land of Goshen" denotes the southern border of the area conquered by Joshua and the Israelites, that is, a region in southern Palestine. It remains unclear how this relates to the "Land of Goshen" located in Egypt. If the Egyptian and the Palestinian Goshen are equated, a connection to a prince of the Arab Kedar named Geschem (Neh 2,19; 6,1.2.6) in Persian times (5th / 4th century BC) would be possible . The "Land of Goschen" means in this case the area ruled by Prince Geschem. Its area of influence was south of the Persian province of Judah, but it is also documented on an inscription from Tell el-Maschuta. This assumption therefore presupposes that the biblical narrative depicts the conditions of the early Hellenistic (Ptolemaic) period by identifying the area previously controlled by Geschem under the name "Land Goschen" as a settlement area of Jacob / Israel.

Sukkot

The Israelites first set out from Ramses for Sukkot (Ex 12:37). Sukkot is identified by many researchers with the Egyptian Tjeku, which originally referred to the region of the Wadi Tumilat around Pithom (for example in the Anastasi VI papyrus, see section "Pithom").

The word Sukkot is likely to be of Semitic origin and was therefore taken over into Egyptian. It roughly means tabernacle (Hebrew Sukka , Pl. Sukkot). This could reflect the fact that Semitic-speaking people, shepherds and traders on their way to Egypt have always set up camp along Wadi Tumilat. The finds of seasonal dwellings by Asians in Tell el-Maschuta from the Second Intermediate Period also fit in with this . Alan Gardiner had strong reservations about equating Sukkot with Tjeku , since Tjeku was not written in syllabic, as would be expected with a foreign place name.

Above all, Manfred Bietak has topographical and geographical objections: The route from Ramses to Sukkot / Tjeku is not a realistic plan, because one would have had to cross the extensive swamps of the Bahr el-Baqar. In addition, Wadi Tumilat is not on the (direct) route from Pi-Ramesse to Sinai. Bietak therefore considers it possible that two different routes merged in the Exodus narrative. One is linked to the city of Ramses, while the other started from the second “storage city” Pithom.

According to Moshier and Hoffmeier, on the other hand, the Israelites avoided the heavily fortified Horus Trail, which leads directly out of Egypt, by taking the route via Tjeku .

Etham

After the Israelites had moved on from Sukkot, they set up camp in Etham "on the edge of the desert" (Ex 13:20).

Some researchers suggested that Etham was referring to a fortification in the area of Wadi Tumilat. So it would be a spelling for Egyptian ḫtm (pronounced: chetem). For linguistic reasons, however, this identification is problematic.

Manfred Görg suggested that Etham is a short form of Pithom (omitting the element "Pi") and that it is the actual spelling for Atum at the time of the 21st Dynasty. This, in turn, is problematic, since pithom is spelled correctly in Ex 1.11. However, an association with Atum is possible: Phonetically, the most natural correspondence (Egyptian) with “Atum”. Atum was the patron god of the Tjeku region and his influence over the centuries is also reflected in the fact that the name Atum has been preserved in the Arabic name “Wadi Tumilat”. Kenneth A. Kitchen suggests a spelling for i (w) itm "Isle of Atum", since iw is a toponym that can be associated with a deity.

The remark that Etham is on the edge of the desert could indicate that it is just outside Wadi Tumilat, possibly near Lake Timsah .

Possible historical background

The Hyksos

The word Hyksos is the Greek rendering for the ancient Egyptian Heka-chaset ( Ḥq3-ḫ3st , "ruler of foreign lands"). It is a ruler title that was used in later times for immigrants from Asia. Especially in the case of the historian Manetho (3rd century BC) who wrote in Greek , this refers to a group of immigrants who lived towards the end of the 18th century BC. BC invaded Egypt from the northeast and settled in the Nile Delta. Its center was the city of Auaris , which is in close proximity to Pi-Ramesse. In the politically unstable Second Intermediate Period , the Hyksos were able to make themselves politically independent. After staying in Egypt for around 200 years, they were finally expelled by a Theban dynasty. This culture of the East Delta, which is influenced by the Near East, can be archaeologically proven and described. Most of the birth names of the kings of the 15th dynasty can be interpreted as Semitic.

So there is a large group of Semitic immigrants who settled in the biblical area "Goschen" and after about 200 years emigrated to the Middle East. A connection between the Hyksos and the Israelites seems obvious and was already made by Flavius Josephus . After Jan Assmann, however, Flavius Josephus was not the first Jew whom Egyptian traditions reminded of the Exodus. These stories were still very much alive in Egypt in the later days , when the Jews fled to Egypt after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple and came into contact with Egyptian traditions. However, there are also differences:

- The Hyksos were not enslaved by the Egyptians, but ruled over them.

- The Hyksos were not freed from Egypt after lengthy negotiations and coercion, but were driven out of it by force.

Many researchers point out that the 400 or 430 years given for the Israelites' stay in Egypt (Gen. 15.13 and Ex. 12.40) go surprisingly well with the 400 years given on the so-called 400 -Year stela . This stele comments on the restoration of the cult for Seth - Baal , who perished after the Hyksos were driven out. The memorial puts the age of the Seth Baal cult in Auaris at 400 years. It is the first and for a very long time the only historical anniversary known to history.

This Seth-Baal played a central role in the religious imagination of Canaan and in particular southern Palestine, and there is even evidence of an equation with YHWH. For Jan Assmann, the “four hundred years” of his stay in Egypt therefore represent a resonance phenomenon in the cultural memory associated with the Egyptized Baal: “It is anything but improbable that under Ramses II the four hundredth anniversary of Seth -Ba'al cult of Auaris also radiated into the Egyptian-ruled Canaan and was thus able to form and keep the association of Egypt and four hundred years of residence in the cultural memory of this area. "

With the monotheism Jan Assmann connects another motive that could have played a role in the History and Memory. In the dispute between Apopi and Seqenenre , a literary story from the late 19th dynasty (around 1200 BC), it is said that the Hyksos ruler Apopi I allegedly practiced a monotheistic religion: “King Apopi made Seth for himself Lord, by not serving any other god in the whole land except Seth. ”This reminiscence could also be a response to the Amarna period , in which King Akhenaten carried out a religious overthrow and only worshiped the sun god Aton . As all traces of this overthrow were later destroyed, this traumatic experience did not find its way into the official Egyptian tradition. Nevertheless, according to Assmann, it left traces in the collective memory: The postponed Amarna recollection was increasingly projected onto the Hyksos and the god Baal / Seth. They subsequently appeared as "Seth monotheists" and "religious wicked". Othmar Keel also sees a connection between Seth and JHWH based on iconographic studies: First, Seth was merged with the Syrian-Palestinian god Baal to form a new kind of “god molecule”, a warlike weather god. This image of God in turn shaped the image of the Jahweh of the Iron Age I (approx. 1200–1000 BC).

Overall, Jan Assmann is considering the following options:

- Canaanite memories of the two hundred year stay in Egypt and the final forced expulsion from it could have been preserved in various forms of oral tradition, at least in certain tribes.

- Egyptian memories of the Hyksos as tyrants and religious offenders could have provoked a Jewish counter-memory or counter-narrative in which, conversely, the Israelites appear as suffering oppressed and the Egyptians as tyrants.

For Manfred Görg , Hyksos and Amarna memories enter into a symbiosis as negative phenomena in order to simultaneously serve as a traditional foil and as a myth-forming constellation for the historically subsequent processes of the unloved dominance of the Assyrians , Persians and Greeks . For Donald B. Redford , the memory of the Hyksos expulsion is likely not only preserved in Egyptian sources, but also lived on in the folklore of the West Semitic population of Palestine. Thus the Exodus narrative is the "Canaanite" version of this event. The Hyksos memory became the central basis of myths in the Canaanite culture. Over time this became blurred and subconsciously altered with the intention of "preserving the face".

Manfred Bietak, on the other hand, clearly rejects any identification of “proto-Israelites” with the Hyksos. The population under the Hyksos rule was an urban society associated with trade and seafaring. The Hyksos experienced the glory of rule over the Delta and the Nile Valley for over 100 years. This is in no way compatible with the tradition of the Israelites and their experiences of oppression in Egypt.

Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman also see chronological problems: According to Egyptian sources, the expulsion of the Hyksos dates to around 1570 BC. In the 1st book of Kings 6 : 1 it says that the construction of the first temple dates in the fourth year of Solomon's reign, 480 years after the exodus from Egypt. This places an excerpt from Egypt around 1440 BC. Near. On the other hand, the Exodus story explicitly mentions the city name Ramses. The first pharaoh named Ramses ( Ramses I ) did not climb until 1320 BC. The throne.

Near East under Egyptian rule in the late Bronze Age

Between 1500 and 1100 BC Canaan was under Egyptian rule for around 400 years. Especially with the campaigns of Thutmose III. an Egyptian imperialism developed in the Middle East. The forms of colonization at that time included not only local oppression, but also the deportation of workers into the Nile Valley. Some of these returned to their homeland when Egypt around 1100 BC. BC lost control of his Canaanite vassals.

Cultural memory of the Egyptian colonial rule

Ronald Hendel in particular advocates the thesis that the Exodus story is primarily linked to memories of the Egyptian colonial rule in Canaan during the late Bronze Age (15th – 12th centuries BC). The Exodus myth took its decisive motives from an anti-colonial, "nativist" resistance movement against the colonial power and gained all the more assertiveness when colonial oppression began to develop from the middle of the 8th century BC. Later repeated among the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Seleucids and Romans.

Nadav Na'am sees a problem in the development of a fundamental collective memory such as the Exodus narrative from fragmentary groups. The forced laborers were probably used in various pharaonic projects and in this case would not have been able to live through a collective collective experience, as described in the Bible. Such a communal experience could therefore only arise from the inhabitants of Canaan themselves, who suffered under the Egyptian occupation, which also included the deportation of groups of people to Egypt. After Na'am, the Egyptian rule found the way into collective memory in a different form - with Canaan and Egypt in exchanged roles and "reverse" route. In addition, the story has been rebuilt with the background of Assyrian oppression.

Donald B. Redford objects that the biblical story has no knowledge of Egypt and the Levant in the 2nd millennium BC. Was processed. There is no mention of Egyptian rule spanning the eastern Mediterranean, no Egyptian campaigns to stop burgeoning rebellions, no governors, no Egyptian principalities ruling Canaanite cities, no oppressive tributes and no cultural exchanges.

Apiru and Hebrews

The Apiru are a group of people who appear in Egyptian, Babylonian and Canaanite sources from the 14th to 12th centuries BC. Appear. It is known in ancient Egyptian sources as ʻprw (aper (u)) and in cuneiform sources as ḫabiru. Many researchers see an etymological relationship to the Hebrew self- designation ʻibrî (see Hebrews ). In the Old Testament there are 33 or 34 documents in which the term “Hebrews” or “Hebrew” stands for people who are otherwise called “Israelites”. In the Exodus story, too, the terms “Hebrews” and “Israelites” seem to be used synonymously. There are even six pieces of evidence in which YHWH introduces himself as "God of the Hebrews".

However, the ʻprw / ḫabiru in ancient oriental studies are largely interpreted as an ethnically heterogeneous group that is not integrated into the contemporary world of states. So it is not necessarily an ethnic group , but above all a pejorative term for a way of life and social position. This is why many historians and theologians are reluctant to equate ʻprw / ḫabiru with Hebrews. In the Exodus story, on the other hand, the expression "Hebrews" is clearly used as a popular name, as an ethnicon: "There is only a rudimentary or sociological understanding that characterizes the" Hebrews "as a group of foreign slave laborers."

For Jan Assmann it seems plausible that a group of Canaanites who opposed the Egyptian occupying power and their vassals and led a semi-nomadic wandering life in the spirit of an opposition use this swear word as a self-designation:

“The term 'apiru (“ wanderers ”,“ tramps ”,“ bandits ”,“ outlaws ”) fits not only phonetically but also semantically particularly well to a group that does not (only) belong to a biological relationship, but rather is (especially) based on a common (alternative, oppositional) way of life. These ḫabiru or 'apiru appear in the sources, especially in the correspondence found in an archive in Amarna between the Egyptian court, the Palestinian vassals and the neighboring empires Mitanni, Hatti and Babylonia, as a not only nomadic but also rebellious movement, the is directed primarily against the city kings who are dependent on Egypt and thus also against Egypt. Even without going so far as to simply identify the ḫabiru or 'apiru with the Hebrews, the question arises as to whether anti-Egyptian memories of this group might not have entered the later Exodus-Moses mythology. "

Finkelstein and Silberman also do not rule out a possible connection between the Hebrews and Apiru: "It is possible that the Apiru phenomenon was remembered in later centuries and included in the biblical texts."

Labor in the 18th and 19th dynasties

The fact that, as a result of victorious campaigns, rich tributes in slaves were demanded from the conquered is already documented for the 19th century and increasingly for the period from the 15th century to the Amarna period . The vanquished and tributaries are in most cases Canaanites. A stele of Pharaoh Amenophis II gives figures for the deportation of prisoners, which according to some historians point to a policy of mass deportation: around 100,000 men, of which 15,000 are Shasu Bedouins, 3,600 Apiru.

From the time of Ramses II , two papyri have been preserved that explicitly mention the Apiru people who had to carry out construction work: In the Leiden papyrus 348 it is said that Apiru have to haul stones for a pylon . For James K. Hoffmeier , the building, which cannot be clearly identified, is a temple, for Ricardo Caminos it is a palace. A parallel to this is the damaged papyrus Leiden 349, which also names Apiru in the civil service. Accordingly, Bible historians such as Georg Fohrer and Helmut Engel have concluded that the Israelites were prisoners of war in Egypt.

Hoffmeier assumes that from the early 18th dynasty to the accession of Ramses II to the throne in Egypt, it was teeming with Semitic-speaking people. Therefore the presence of “Israelites” / “Hebrews” in this “mix” during the New Kingdom is entirely plausible. The Semites who already lived in Egypt were treated the same as the prisoners of war who had to do labor.

However, Finkelstein and Silberman point out that the Merenptah stele mentions Israel as a group that already lived in Canaan. In addition, there is not a single evidence of Israelites in Egypt: neither on monumental inscriptions, nor in grave inscriptions, nor on papyrus: Israel does not exist - neither as a possible enemy of Egypt, nor as a friend, nor as an enslaved nation. Nor are there any archaeological finds in Egypt that could be directly linked to a specific ethnic group that settled in the Eastern Delta - in contrast to a concentration of migrant workers from many areas.

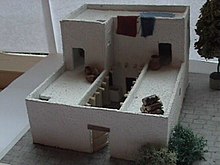

Canaanite four-room house and temple slaves of the 20th Dynasty

Manfred Bietak sees archaeological evidence for the deportation of people from the Canaanite region to Egypt in the discovery of the so-called four - room house within the temple district of Eje and Haremhab in Medinet Habu ( West Thebes ), which is dated to the time of Ramses IV . The excavators suspected that there would be quarters for workers who were supposed to demolish the temple for the extraction of building material, presumably for a new temple project by Ramses IV. The floor plan shows a rectangular courtyard surrounded on three sides by spatial elements. The same room configuration can be found in the so-called Israelite four-room house. Even with its size of 9.5 × 10 m, the Theban floor plan corresponds very well to the four-room house. The only difference is that the entrance does not lead through the southern perimeter wall into the courtyard, but from the north through the central room element. According to Bietak, however, there are such specific details on the house floor plan that “there is no doubt that it is identified as a four-room house in the Iron Age culture of Palestine”.

Temple slaves from the region of Palestine, who were killed by a campaign by Ramses III, are primarily considered as builders . come. These could have been sea peoples , especially Philistines , or Shasu Bedouins. The Harris I papyrus provides information on the distribution of such prisoners of war to the temples of Egypt. Bietak considers identifying the workers with the Shasu Bedouins in particular because they come from the Seïr desert , which is connected to YHWH in biblical sources (Deut. 33.2; Ju. 5.4-5; Habakuk 3, 3) - and possibly since the 15th or 14th century BC. BC also in Egyptian sources. Therefore, Bietak thinks it is possible to look for the origin of YHWH worship in the Seir region, and perhaps even the core group of proto-Israelites.

However, no prisoners of war or temple slaves are mentioned in the Exodus narrative. But it could be incidental evidence of a widespread phenomenon in Egypt. Although the four-room house is usually referred to as an “Israelite dwelling house”, the ethnic allocation is not clear, “although the majority of the Israelites came from this pool”. For Bietak there is therefore some evidence that proto-Israelites were represented among the contingent of temple slaves of the 20th dynasty.

Proto-Israelite settlement of the Palestine region

The first archaeologically proven traces of an early or proto-Israelite settlement in the Palestine region date back to the 12th and 11th centuries BC. BC back. According to Lawrence E. Stager, 93% of people are between 12 and 11 months old. In the 19th century, settlements in the Palestinian hill country inhabited new unfortified villages. Most were inhabited for several generations up to the royal times. For these settlements, which are described as “early” or “proto-Israelite”, a number of features have been identified that are interpreted as signs of the ethnic uniformity of the population of this region: The inhabited areas are usually small (around 100 inhabitants) unpaved villages, the houses of which are grouped in blocks of 2 or 3 with shared walls and partly shared facilities. The typology of these houses - with 3 to 4 rooms and an inner courtyard divided by stone pillars (pillar-courtyard houses) has no equivalent in the Canaanite Bronze and Iron Ages I and points to a social organization based on large families. The lack of military installations, temples, palaces and other monumental structures also suggested that the population of these villages had a tribal, non-hierarchical form of society.

Finkelstein and Silberman therefore assume that the ethnic group Israel settled in the late 13th century BC. Developed as an independent group. So around 1200 BC A significant social change took place for which there is no evidence of a violent invasion or infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group. Instead, a revolution in the way of life seemed to have taken place: “In the previously sparsely populated areas of the Judean Mountains in the south to the mountains of Samaria in the north, far from the Canaanite cities that were on the verge of collapse and dissolution, two hundred and fifty emerged Communities on mountaintops. The first Israelites lived here. ”(See also Landing by the Israelites )

Migrations and Sea Peoples

Towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC The Mediterranean was hit by a great wave of migration that generally marked the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age in the eastern Mediterranean. Peoples operating at sea formed a coalition with peoples operating on land and destroyed many cities and empires in the eastern Mediterranean. The Egyptians also had to fight hard against the sea peoples .

The prophet Amos also connects the memory of these wanderings with the Exodus:

“Are you more to me than the Cushites , you Israelites? - Saying of the Lord. I did bring Israel up from Egypt, but also the Philistines from Kaftor and the Arameans from Kir . "

The Philistines bring a new material culture and drive the inhabitants of the coastal region into the mountains, where in the 12th and 11th centuries BC. The proto-Israelite settlements emerged. Accordingly, the Israelites do not come from anywhere else, but have only moved within Canaan. The Merenptah stele with the mention of Israel comes from this or a little earlier time (around 1220 BC). Therefore Assmann believes it is possible "that a Canaanite tribe of this name once entered Egypt and later emigrated from there again, possibly under the leadership of a man named Moses."

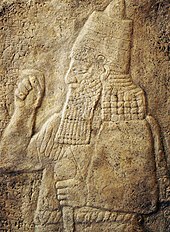

Assyrian threat

Since the Exodus tale probably its earliest form in the 7th century BC. Has accepted it, Helmut Utzschneider sees it from Old Testament specifications (initially) as a reaction to an Assyrian threat to the late Judean state. It could, for example, reflect the siege of Jerusalem in 701 by the Assyrian great king Sennacherib . This is justified primarily on the basis of a theological experience of liberation. It thus has the function of a theological auxiliary construction and helps to make the oppressive and confusing reality transparent and to find one's way around it.

"In the mirror of the Exodus story, the reader gets to know himself as a political subject between despair and hope. In all his shortness of breath he shares in God's long breath. This is probably also where - to speak with Hegel - 'general and substantial', the epic overall view that the Exodus narrative is able to convey. "

Eckart Otto develops a similar view from Assyrian sources . In his opinion, the Exodus story refers to events under King Manasseh of Judah (approx. 696–642 BC), during whose reign the Judeans had to perform forced labor for the Assyrian king Asarhaddon (680–669 BC). The figure of Moses is said to be a counter-draft of political theology to the New Assyrian royal ideology in the 7th century BC. And to be understood as an adaptation of the Sargon legend .

Forced laborers under Pharaoh Necho II.

Necho II ruled as the second pharaoh (king) of the Saïten dynasty from 610 to 595 BC. He made the first attempt to build a canal through Wadi Tumilat to connect the Nile to the Red Sea. It can be assumed that foreign prisoners of war and slave labor were used for this construction project. Herodotus (Hist. 2,158) speaks of 120,000 workers who perished in the construction. According to the theologian Wolfgang Oswald , the number should not be assessed quantitatively, but qualitatively. It therefore gives an impression of the cruelty of the forced labor used in building canals. A historical clue is perhaps the mention of the city of Pitom, which may have been founded in the course of the canal construction.

There is no explicit evidence of Judean prisoners of war, but in 2 Kings 23: 33-35 it is reported that Necho II abducted the Judean king Jehoahaz to Egypt and demanded a very high tribute. Judah was definitely there until the Battle of Karkemiš in 605 BC. A vassal state of the strings.

For Oswald there is therefore a high probability “that either after the Egyptian defeat at Karkemish or after the demolition of the canal and the demonization of Nechos II that followed, such forced laborers would return to Judah.” This is not to say that the Exodus tradition is only around the turn of the 7th to the 6th century, “rather, the supremacy of Nechos II over Judah and his canal construction project seem to have been the occasion for the updating of the old Exodus tradition, which is reflected in the formulation of the Exodus tradition as it can be reconstructed from the Book of Exodus, ".

Multiple past

Various researchers assume that the Exodus narrative is not tailored to a specific historical situation. It has outgrown Israel's long and painful history of experience and sums up these experiences in a general and substantial way: "So it is then ready for its readers who, with its help, interpret their respective situation." According to Oswald, the Exodus narrative could cover all three hegemony of the 7th century BC Have as background: the Assyrian (up to about 612), the Egyptian (up to 605) and the Babylonian (from 604).

Rainer Albertz illustrates this with the nameless pharaoh: “The pharaoh of the Exodus story is obviously deliberately not depicted as a historical person, but as a type of despot who brutally and cynically suppressed the ancestors of Israel (5: 3-19) and cheekily their god JHWH challenged (5: 1-2). This openness of the narrative is intended to enable the Israelite descendants to equate 'the pharaoh' with the currently threatening potentates in changing political situations, be it the Egyptian pharaohs like Ramses II , Merenptah or Ramses III. , their own kings like Solomon and Ahab , or the Assyrian and Babylonian foreign rulers like Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar II. With the help of the Exodus story, Israel should be able to reassure itself of its identity as the liberated people of God in the face of changing threats. "

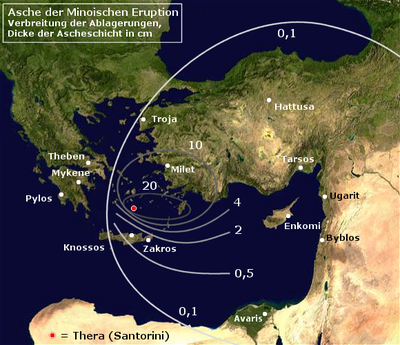

Middle Bronze Age and Minoan Eruption

So u. a. the geologist Sivertsen (2009) a connection between the plagues described in the Pentateuch of the Old Testament , the Second Intermediate Period in the history of Egypt and the Minoan eruption (also Thera or Santorin eruption) in the Middle Bronze Age . In the Old Testament narrative that was later written down, a large number of the phenomena as described in the ' Plagues ' can be explained by the consequences of the eruption . This is dated differently (see also table dating of the Minoan eruption ), some more recent 14 C dates again speak for the years 1620 to 1600 BC. BC : The radiocarbon dating of the branch of an olive tree buried by volcanic eruption on Thera in 2006 , which was found in the pumice layer of the island in November 2002 , revealed an age of 1613 BC. Chr. ± 13 years.

It is unclear how the Minoan eruption also directly or indirectly affected the civilization of the Minoans , as they left behind neither written nor pictorial representations of the catastrophe. The already mentioned archaeological evidence “only” speaks against a sudden destruction of the Minoan culture by the eruption. There were close ties between the Minoan culture, which can be traced far into the eastern Mediterranean, and Egypt in particular. Until around 1400 BC Chr. In Egyptian tombs representations of Cretan embassies can be found again and again.

| System of Evans | Chronology v. BC ( New Palace period ) | Egyptian Dynasties ( Second Intermediate Period ) | System of Plato | Chronology v. Chr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Minoan III | 1700-1600 | 13-17 dynasty | Older palace period III | 1800-1700 |

Protosinaitic script

On the Sinai Peninsula, which the Israelites wandered through to Num 32.13 EU for 40 years, inscriptions in the so-called Protosinaite script were found. It is believed that this writing dates from around 1700 BC. BC under the influence of the Egyptian hieroglyphs on the Sinai Peninsula and was the forerunner of the ancient Hebrew script .

See also

- Land conquest by the Israelites

- 2. Book of Moses

- Section History of Pentateuch Research in the Torah article

literature

- Jan Assmann : Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015.

- Jan Assmann: Exodus and Memory. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, pp. 3–16.

- Jan Assmann: Moses the Egyptian. Deciphering a memory trace. Hanser, Munich 1998.

- Manfred Bietak : On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, pp. 17–38.

- Manfred Bietak: Israelites Found In Egypt, Four-Room House Identified in Medinet Habu. In: Biblical Archeology Review. Volume 29 (Sept / Oct), pp. 40-47, 49, 82-83.

- Manfred Bietak: Comments on the "Exodus". In: Anson F. Rainey (ed.): Egypt, Israel, Sinai. Archaeological and Historical Relationships in the Biblical Period. Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 1987, pp. 163-172.

- Manfred Bietak: The sojourn of “Israel” and the time of the “conquest” from today's archaeological point of view. In: Egypt and Levant. No. 10, 2000, pp. 179-195.

- John J. Bimson: Moving Out and Landing - Myth or Reality? In: Peter van der Veen, Uwe Zerbst (Ed.): Biblical Archeology at the Crossroads? Pros and cons of re-dating archaeological epochs in Old Testament Palestine. (1988) 2nd edition, Hänssler, Holzgerlingen 2003, ISBN 3-7751-3851-X , pp. 395-414.

- Gordon F. Davies: Israel in Egypt. Reading Exodus 1-2. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1992, ISBN 0-567-59988-4 .

- William G. Dever: Who Were the Israelites and Where Did They Come From? William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids / Cambridge 2003.

- Herbert Donner : History of the people of Israel and its neighbors in outline, Volume 1: From the beginnings to the formation of states. 3rd, revised and supplemented edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000–2001, ISBN 3-525-51679-7 .

- Israel Finkelstein , Neil Asher Silberman : No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Munich, Beck 2002 (Original edition: The Bible Unearthed. Archeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origins of Its Sacred Text. Simon & Schuster, 2002).

- Israel Finkelstein, Amihai Mazar : The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archeology and the History of Early Israel. Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta GA 2007, ISBN 1-58983-277-9 .

- Ernest S. Frerichs, Leonard H. Lesko, William G. Dever (Eds.): Exodus: The Egyptian Evidence. Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake IN 1997, ISBN 1-57506-025-6 .

- Lawrence T. Geraty: Exodus Dates and Theories. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider , William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, pp. 55–64.

- Manfred Görg : The so-called exodus between memory and polemics. In: Irene Shirun-Grumach (Ed.): Jerusalem Studies in Egyptology (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 40). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, pp. 159-172.

- Ronald Hendel: The Exodus in Biblical Memory. In: Journal of Biblical Literature. No. 120, number 4, 2001, pp. 601-622.

- James K. Hoffmeier : Israel in Egypt. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1999.

- James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005.

- Kenneth A. Kitchen : On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Eerdmans, Cambridge 2003.

- Samuel E. Loewenstamm: The Evolution of the Exodus Tradition. Magnes Press, Hebrew University, 1992, ISBN 965-223-784-1 .

- Nadav Na'aman: The Exodus Story: Between Historical Memory and Historical Composition. In: Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. No. 11, 2011, pp. 39-69.

- Nadav Na'aman: Out of Egypt or Out of Canaan? The Exodus Story Between Memory and Historical Reality. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, pp. 527-536.

- Michael D. Oblath: The Exodus Itinerary Sites: Their Locations from the Perspective of the Biblical Sources. Peter Lang, New York 2004, ISBN 0-8204-6716-2 .

- Wolfgang Oswald: Extract from the vassal: The Exodus story (Ex 1–14) and ancient international law. In: Theological Journal. Volume 67, Issue 3, Basel 2011, pp. 263–288.

- Donald B. Redford : Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ) 1992.

- Donald B. Redford: An Egyptological Perspective on the Exodus Narrative. In: Anson F. Rainey (ed.): Egypt, Israel, Sinai. Archaeological and Historical Relationships in the Biblical Period. Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 1987, pp. 137-162.

- Donald B. Redford: Observations on the Sojourn of the Bene-Israel. In: Ernest S. Frerichs, Leonard H. Lesko, William G. Dever (Eds.): Exodus. The Egyptian Evidence. Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake (IN) 1997, pp. 57-66.

- Lawrence E. Stager: Forging an Identity. The Emergence of Ancient Israel. In: MD Coogan (Ed.): The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press, New York 1998, pp. 123-175.

- Helmut Utzschneider : God's staying power. The Exodus story (Ex 1–14) from an aesthetic and historical perspective (= Stuttgart Biblical Studies. Volume 166). Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 112–118.

- Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, Manfred Görg : Israel in Canaan (Long) Before Pharaoh Merenptah? A Fresh Look at Berlin Statue Pedestal Relief 21687. In: Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. Volume 2, Number 4, 2010, pp. 15-25 ( online ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 53.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002, p. 110.

- ^ A b Donald B. Redford: Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ) 1992, p. 408.

- ↑ a b Rainer Albertz: Exodus 1–18. In: R. Albertz: Exodus. (= Zurich Bible Commentaries. AT;, 2., 2.2). Theological Publishing House Zurich, Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-290-17642-6 , p. 30.

- ^ Rainer Albertz: Exodus 1-18. Theological Publishing House Zurich, Zurich 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Lawrence T. Geraty: Exodus Dates and Theories. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp (Eds.): Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, pp. XI and 235.

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Introduction to the Old Testament. 5th edition, de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 1995, p. 10.

- ↑ Christian Frevel: Outline of the history of Israel. In: Erich Zenger, u. a .: Introduction to the Old Testament. 7th edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 600–601.

- ^ Donald B. Redford: An Egyptological Perspective on the Exodus Narrative. In: Anson F. Rainey (ed.): Egypt, Israel, Sinai. Archaeological and Historical Relationships in the Biblical Period. Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 1987, p. 137.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein: The Wilderness Narrative and Itineraries and the Evolution of the Exodus Tradition. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp (Eds.): Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 39 refers to Kenneth A. Kitchen: Egyptians and Hebrews, from Ramses to Jericho. In: The Origin of Early Israel - Current Debate (= Beer-Sheva. XII). Ben Gurion University, Jerusalem 1995, pp. 65-131; Baruch Halpern: The Exodus and the Israelite Historians. In: Eretz Israel. Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies , Volume 24, 1993, pp. 89 * -96 *; James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005; James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press, New York 1997.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein: The Wilderness Narrative and Itineraries and the Evolution of the Exodus Tradition. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp (Eds.): Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 39 refers to Donald B. Redford: Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1992, pp. 408-422; John Van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. In: JA Dearman, MP Graham (Eds.): The Land that I Will Show You: Essays on the History and Archeology of the Ancient Near East in Honor of J. Maxwell Miller. Academic, Sheffield 2001, pp. 255-276; Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: The Bible Unearthed: Archeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts. The Free Press, New York 2001, pp. 48-71; Mario Liverani: Israel's History and the History of Israel. Equinox, London 2005, pp. 277-282.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein: The Wilderness Narrative and Itineraries and the Evolution of the Exodus Tradition. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp (Eds.): Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 40.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein: The Wilderness Narrative and Itineraries and the Evolution of the Exodus Tradition. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp (Eds.): Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 50.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 54.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 56.

- ^ Thomas Wagner: Israel (AT) In: www.bibelwissenschaft.de with verse on CAT 4.632; G. Sauer: Comments on Ugaritic texts edited in 1965. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society. Volume 116, Number 2, 1966, pp. 239-240; H.-J. Sable: ישׂראל. In: Theological dictionary of the Old Testament. (ThWAT) Volume 3, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1982, p. 988.

- ↑ Thomas Wagner: Israel (AT) In: www.bibelwissenschaft.de

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Israel in Egypt. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1999, p. 28 with note 26.

- ^ Thomas Wagner: Israel (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on May 30, 2012.

- ^ W. Gesenius, F. Buhl: Hebrew and Aramaic Concise Dictionary on the Old Testament. Vogel, Leipzig 1915, p. 303.

- ↑ Manfred Görg: Israel in hieroglyphs. In: Biblical Notes'. Volume 106, 2001, pp. 21-27.

- ↑ Jan Dönges: Since when has Israel existed: Extract from Egypt's archives . In: Spectrum - Die Woche , 19th KW 2011 ( online ).

- ↑ Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, Manfred Görg: Israel in Canaan (Long) Before Pharaoh Merenptah? A Fresh Look at Berlin Statue Pedestal Relief 21687 . In: Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections . Volume 2, Number 4, 2010, pp. 15-25 ( online ).

- ↑ Peter James and Peter van der Veen: Palestine: Historical Image in Shards? . In: Spectrum of Science , December 2008 ( online ).

- ↑ Detlef Jericke: The location information in the book Genesis. A historical-topographical and literary-topographical commentary. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, 2013, p. 241.

- ^ Alan H. Gardiner: The Delta Residence of the Ramessides. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology 5, 1918, pp. 137-138, 180, 188, 265.

- ↑ Donald B. Redford: Exodus I.11. In: Vetus Testamentum 13, 1963, pp. 409-413.

- ↑ John Van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. In: JA Dearman, MP Graham: The Land that I Will Show You. Essays on History and Archeology of the Ancient Near East in Honor of J. Maxwell Mille (= Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series. Volume 343). Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield 2001, pp. 255-276.

- ^ Manfred Bietak, On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ a b Rainer Albertz: Exodus 1–18. Theological Publishing House Zurich, Zurich 2012, p. 28.

- ↑ Detlef Jericke: The location information in the book Genesis. A historical-topographical and literary-topographical commentary. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, 2013, p. 241.

- ↑ Eric P. Uphill: Pithom and Raamses. Their Location and Significance. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies Volume 27, Number 4, 1968, p. 291.

- ↑ Raphael Giveon: Les bedouins Shosou of documents égyptiens. Brill, Leiden 1971, pp. 131-134.

- ^ Karl Jansen-Winkeln: Pitom . In: www.bibelwissenschaft.de (created: March 2007; accessed on July 12, 2019).

- ^ Donald B. Redford: Pithom. In: Wolfgang Helck (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie (LÄ). Volume IV, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1982, ISBN 3-447-02262-0 , Sp. 1054-1058.

- ^ Rainer Albertz: Exodus 1-18. Theological Publishing House Zurich, Zurich 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Manfred Bietak, On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, pp. 25–26 and note 39.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 123.

- ↑ Detlef Jericke: The location information in the book Genesis. A historical-topographical and literary-topographical commentary. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, 2013, p. 239.

- ↑ Jericke: The location information in the book of Genesis. 2013, p. 239 refers to Wolfgang Helck : Die oldägyptischen Gaue. (= TAVO 5) Wiesbaden, 1974, 197 f. and Farouk Gomaà: The Settlement of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom. II. Lower Egypt and the adjacent areas. (Supplements to the Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orient, Series B, issue 66/2) Wiesbaden, 1987, pp. 127–129.

- ↑ Jericke: The location information in the book of Genesis. 2013, p. 239 refers to Helmut Engel: The ancestors of Israel in Egypt. Research history overview of the representations since Richard Lepsius (1849). (= Frankfurt Theological Studies 27) Frankfurt a. M., 1979, pp. 50–52 and Manfred Görg: The relationships between ancient Israel and Egypt. From the beginning to exile. (= Income from research 290), Darmstadt, 1997, p. 135 f.

- ^ Donald B. Redford: An Egyptological Perspective on the Exodus Narrative. In: Anson F. Rainey (ed.): Egypt, Israel, Sinai. Archaeological and Historical Relationships in the Biblical Period. Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 1987, pp. 139-140; Detlef Jericke: The location information in the book Genesis. A historical-topographical and literary-topographical commentary. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, 2013, p. 240.

- ↑ Detlef Jericke: The location information in the book Genesis. A historical-topographical and literary-topographical commentary. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, 2013, p. 240.

- ^ Manfred Bietak, On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Alan H. Gardiner: The Geography of the Exodus. In: Recueil d'études égyptologiques dédiées à la mémoire de Jean-François Champollion. 234, p. 213, no. 2.

- ^ Manfred Bietak, On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Stephen O. Moshier, James K. Hoffmeier: Which Way Out of Egypt? Physical Geography Related to the Exodus Itinerary. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 106.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, p. 69 with reference to Kenneth A. Kitchen: Egyptians and Hebrews, from Raamses to Jericho. In: The Origin of Early Israel - Current Debate (= Beer-Sheva. XII). Ben Gurion University, Jerusalem 1995, p. 78 and Yoshiyuki Muchiki: Egyptian Proper Names and Loanwords in North-west Semitic. Scholar Press: Atlanta (GA), 1999, p. 230.

- ↑ Manfred Görg: Etham and Pithom. In: Biblical Notes 51, 1990, pp. 9-10; P. Weimer: The sea miracle story. An editorial critical analysis of Ex 13.17–14.31. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, 1985, pp. 264-265.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, p. 69.

- ↑ Yoshiyuki Muchiki: Egyptian Proper Names and loanwords in North-West Semitic. Scholar Press: Atlanta (GA), 1999, p. 230.

- ↑ a b Stephen O. Moshier, James K. Hoffmeier: Which Way Out of Egypt? Physical Geography Related to the Exodus Itinerary. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 105.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Kitchen: On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Eerdmans, Cambridge 2003, p. 259.

- ↑ Manfred Bietak: Tell el-Dab'a II. The place of discovery as part of an archaeological-geographical investigation of the Egyptian eastern delta. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1975.

- ^ Manfred Bietak: Avaris, the Capital of the Hyksos. Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab'a. The British Museum Press, London 1996.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: Foreigners in Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos period. Part 1: The Foreign Kings. (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 42). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998.

- ^ Manfred Bietak, On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 31 with reference to Flavius Josephus, Contra Apionem I, 26–31.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ a b c Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 57.

- ↑ Helmut Engel: The ancestors of Israel in Egypt. Research history overview of the representations since Richard Lepsius (1849). (= Frankfurt Theological Studies. Volume 27). Knecht, Frankfurt am Main 1979, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Thomas Schneider: The First Documented Occurrence of the God Yahweh? (Book of the Dead. Princeton 'Roll 5'). In: Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religion. No. 7, 2008, p. 119.

- ↑ Manfred Bietak: On the Historicity of the Exodus. What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 31.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 57.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume II: New Kingdom. (= Introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Volume 6). 2nd edition, Lit, Münster 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Moses the Egyptian. The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MA) / London 1997, pp. 24-29 (German edition: Moses the Egyptian. Deciphering a memory trace. Hanser, Munich 1998).

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, pp. 57–60.

- ↑ Othmar Keel: To identify the falcon-headed person on the scarabs of the late 13th and 15th dynasties. In: Othmar Keel, Hildi Keel-Leu, Silvia Schroer (eds.): Studies on the stamp seals from Palestine / Israel. Volume II (= Orbis biblicus et orientalis. [OBO] Volume 88). Universitätsverlag / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Freiburg (CH) / Göttingen, pp. 243–280.

- ↑ Othmar Keel: Early Iron Age Glyptik in Palestine / Israel. In: Othmar Keel, Menakhem Shuval, Christoph Uehlinger: Studies on the stamp seals from Palestine / Israel. Volume III: The Early Iron Age. A workshop. (= OBO Band 100). Universitätsverlag / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Freiburg (CH) / Göttingen 1990, pp. 331–421.

- ↑ Michael Brinkschröder: Sodom as a symptom. Same-sex sexuality in the Christian imaginary - a history of religion. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006, p. 199.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 62.

- ↑ Manfred Görg: The so-called exodus between memory and polemics. In: Irene Shirun-Grumach (Ed.): Jerusalem Studies in Egyptology (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 40). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, p. 168.

- ^ Donald B. Redford: Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ) 1992, pp. 408-429.

- ^ Manfred Bietak, On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002.

- ^ Donald B. Redford: The wars in Syria and Palestine of Thutmose III (= Culture and history of the ancient Near East. Volume 16). Brill, Leiden et al. 2003.

- ↑ Christian Langer: Aspects of Imperialism in the Foreign Policy of the 18th Dynasty (= Northeast African / West Asian Studies. Volume 7). International Science Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 2013.

- ^ Ronald Hendel: The Exodus in Biblical Memory. In: Journal of Biblical Literature. Volume 120, Number 4, 2001, pp. 601-622.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 67 with reference to Bernhard Lang: From warlike to nativistic culture. Ancient Israel in the light of cultural anthropology. In: Evangelical Theology. No. 68, 2008, pp. 430-443.

- ↑ Nadav Na'aman: The Exodus Story: Between Historical Memory and Historical Composition. In: Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. No. 11, 2011, pp. 39-69.

- ^ Donald B. Redford: Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ) 1992, p. 257.

- ^ Oswald Loretz: Habiru-Hebrews. A socio-linguistic study on the origin of the gentilizium'ibrî from the appellative ḫabiru (= supplement to the journal for Old Testament science. Volume 160). Wde Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1984, p. 42.

- ↑ a b Detlef Jericke: Hebrews / Hapiru . In: www.bibelwissenschaft.de (created 2016, accessed on July 12, 2019).

- ^ Oswald Loretz: Habiru-Hebrews. A socio-linguistic study on the origin of the gentilizium'ibrî from the appellative ḫabiru (= supplement to the journal for Old Testament science. Volume 160). de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1984, pp. 181-182.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 66.

- ↑ Herbert Donner: History of the people of Israel and its neighbors in outline. Part 1. 4th edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 66.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002, p. 166.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Israel in Egypt. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1999, p. 61.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Israel in Egypt. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1999, pp. 112-113; there cited: Amin Amer: A list of booty from Amenhotep II and the problem of slavery in ancient Egypt. In: Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux. (JEOL) No. 17, Leiden 1963, pp. 141–147.

- ↑ a b c James K. Hoffmeier: Israel in Egypt. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Ricardo Caminos: Late-Egyptian Miscellanies. Oxford University Press, London 1954, p. 491.

- ^ WH Schmidt: Exodus, Sinai and Mose. Considerations on Ex 1–19 and 24. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1983, p. 25.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002, pp. 102-103.

- ^ Manfred Bietak: An Iron Age Four Room House in Ramesside Egypt. In: Eretz Israel (A. Biran Volume) No. 23, pp. 10-12.

- ↑ Manfred Bietak: The stay of "Israel" and the time of the "conquest" from today's archaeological point of view. In: Egypt and Levant. No. 10, 2000, pp. 179-195.

- ↑ a b Manfred Bietak: The stay of "Israel" and the time of the "land grab" from today's archaeological point of view. In: Egypt and Levant. No. 10, 2000, p. 181.

- ^ A b Manfred Bietak: On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt. In: Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, William HC Propp: Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Manfred Bietak: The stay of "Israel" and the time of the "conquest" from today's archaeological point of view. In: Egypt and Levant. No. 10, 2000, p. 182.

- ↑ Lawrence E. Stager: Forging an Identity. The Emergence of Ancient Israel. In: MD Coogan (Ed.): The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press, New York 1998, pp. 123-175.

- ^ William G. Dever: Who Were the Israelites and Where Did They Come From? William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids / Cambridge 2003, pp. 102-128.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002, pp. 123-126.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002, pp. 171-174.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The Archaeological Truth About the Bible. Beck, Munich 2002, p. 174.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Exodus. The Old World Revolution. Beck, Munich 2015, p. 68.

- ↑ Helmut Utzschneider: God's long breath. The Exodus story (Ex 1–14) from an aesthetic and historical perspective (= Stuttgart Biblical Studies. Volume 166). Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 112–118.

- ↑ Helmut Utzschneider: God's long breath. The Exodus story (Ex 1–14) from an aesthetic and historical perspective (= Stuttgart Biblical Studies. Volume 166). Catholic Biblical Work, Stuttgart 1996, p. 112.

- ↑ Eckart Otto: Moses and the Law. The figure of Moses as an alternative political theology to the neo-Assyrian royal ideology in the 7th century BC. Chr. In: Eckart Otto (Ed.): Mose, Egypt and the Old Testament (= Stuttgart Biblical Studies. Volume 189). Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 2000, pp. 43–83.

- ^ A b Wolfgang Oswald: State theory in ancient Israel. The political discourse in the Pentateuch and in the history books of the Old Testament. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Wolfgang Oswald: State theory in ancient Israel. The political discourse in the Pentateuch and in the history books of the Old Testament. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ Helmut Utzschneider: God's long breath. The Exodus story (Ex 1–14) from an aesthetic and historical perspective (= Stuttgart Biblical Studies. Volume 166). Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 1996, p. 118.

- ↑ Wolfgang Oswald: Exodus book . In: www.bibelwissenschaft.de (created: Dec. 2005; accessed on July 12, 2019).

- ↑ Barbara J. Sivertsen : The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Story of Exodus . Princeton University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-13770-4 (online: excerpt from the topic ( Memento from January 22, 2013 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ 2. Book of Moses , Hebrew שְׁמוֹת Schemot , German 'name'

- ^ Riaan Booysen: Thera and the Exodus: The Exodus explained in terms of natural phenomena and the human response. John Hunt Publishing, Alresford 2013, ISBN 978-1-78099-449-9

- ↑ W. Woelfli: Thera as the focal point of the Egyptian and Israelite chronologies. November 8, 2018 PDF; 128 kB, pp. 1–10 here p. 4

- ^ Siro Igino Trevisanato : The Plagues of Egypt. Archeology, History and Science Look at the Bible. Euphrates, Piscataway NJ 2005, ISBN 1-59333-234-3 .

- ↑ Newly dated - 100 years are missing from the ancient calendar . Scientists are well ahead of the Santorini eruption. Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, April 27, 2006, accessed on May 2, 2011 .

- ↑ Walter L. Friedrich: Fire in the sea . The Santorini volcano, its natural history and the legend of Atlantis. 2nd Edition. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8274-1582-9 , p. 86 .

- ^ Friedrich WL, Kromer B., Friedrich M., Heinemeier J., Pfeiffer T., Talamo S. (2006): Santorini eruption radiocarbon dated to 1627–1600 BC. In: Science 312 (5773), pp. 548-548; doi: 10.1126 / science.1125087

- ↑ Charlotte L. Pearson, Peter W. Brewer, David Brown, Timothy J. Heaton, Gregory WL Hodgins, AJ Timothy Jull: Annual radiocarbon record indicates 16th century BCE date for the Thera eruption. Science Advances. August 15, 2018, Vol. 4, no.8, eaar8241

- ↑ Volker Jörg Dietrich: Greece in fire - from Prometheus to the fire devil. Summary of the lecture of February 26, 2013, pp. 25–44 PDF; 15.9 MB, 20 pages here pp. 35–39