Tell el-Maschuta

| Tell el-Maschuta in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place name during the Second Intermediate Period (around 1600 to 1550 BC): |

|

||||

| Place name from 605 BC BC (namesake Necho II. ): |

Per Tem Pr Tm House of Atum (Tem) |

||||

| Place name from 2nd century AD: |

Necropolis "Ero" |

||||

| Place name from 19th century AD: |

Tell el-Maschuta |

||||

| Greek | Heroonpolis | ||||

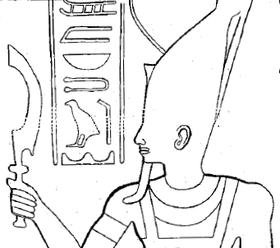

| Tem (Atum) as "Lord of Tju (Tjeku)" | |||||

Tell el-Maschuta ( Arabic تل المسخوطة Tell el-Maschūta , DMG Tall al-Masḫūṭa ) - the ancient Egyptian Per Tem / Pi-Tem - is located in the region of Wadi Tumilat in the eastern Nile Delta about 16 kilometers west of Ismailia and about 18 kilometers east of Tell er-Retaba .

The use of the place was subject to constant changes. Originally in the 16th century BC Founded as a two to three hectare settlement, Tell el-Maschuta was founded at the end of the 7th century BC. As a trading place and place of worship of the deity Atum (Tem) a new foundation, with which the name Per Tem (Atum) in Tjeku was connected under the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II . Herodotus mentioned the "Arab city of Patumos " located in this region in connection with the canal expansion begun by Necho II . In Hellenism contributed by Tem probably name Heroonpolis ; however, this is not certain. The name Ero , which comes from Roman times , is the short form of Heroonpolis .

Earlier results of the archaeological research initially suggested that Tell el-Maschuta was the biblical pitom . Thus, for example, on the salvaged statue of Ankh-nefer chered also by Tem mentioned, from which many historians connect to the cult of the deity Atum in Heliopolis , the biblical On , joined. The from the Ptolemaic period coming Pitom stele can be seen that a few centuries after Necho II. The old name by Tem as a place name for Tell el-Maschuta was in use.

At the beginning of the 2nd century AD, the function of Tell el-Maschuta changed again, which now served as a Roman cemetery. Since the beginning of the 5th century AD, Tell el-Maschuta is only a hill of ruins . From 1977 onwards, it was archaeologically examined several times during excavation campaigns .

Etymology and history of research

In earlier times the place was called Ahou Kachah or Abou Keycheyd . There a monolith was found on which Ramses II is depicted between two sun deities . The archaeologists therefore suspected an ancient Egyptian city with the silted up monolith as a typical distinguishing feature.

Archaeological teams identified the place as Pi-Ramesse , the "place of the Israelites during their oppression", based on the Ramses monolith . The supposed discovery prompted numerous archaeologists to intensify research and excavations in "Pi-Ramesse" around 1860. However, further research led to the conclusion that it was not pi-ramesse.

At around the same time, work on the Bubastis Canal was completed. After the workers and archaeologists left, interest in the hill of the monument , for which the modern translation Hill of the Damned / Heroes is also used, waned.

In 1883, Édouard Naville undertook another campaign in this region on behalf of the Egypt Exploration Society and discovered the ruins of Tell el-Maschuta. He examined the existing monuments , statues , inscriptions and building remains and made a floor plan of the ancient Tell el-Maschuta. However , Naville did not examine the numerous ceramic shards and other small finds in the Straten (horizontal excavation layers). In his final report he came to the conclusion that it must be about the biblical pithom , since the excavated objects also included several monuments from the time of Ramses II.

The French Egyptologist Jean Cledat carried out further investigations in the region of Wadi Tumilat between 1900 and 1910 and was able to recover additional finds. John S. Holladay and his team initiated extensive excavations as part of the Wadi Tumilat project launched by the Canadian University of Toronto . Five excavation campaigns took place from 1978 to 1985 . The research commissioned by the Egyptian Antiquities Administration has recently brought more information about Tell el-Maschuta.

Archaeological Studies

First settlement phase

The excavations show that Tell el-Maschuta was in the 16th century BC. At the end of the Second Intermediate Period (1600 to 1550 BC) by the Hyksos (immigrants from the Near East). The place name at that time could not yet be determined. The small town had the character of an outpost, as there were no special fortifications. The shape of the curved city walls used at this time is characteristic . During the construction phase of Tell el-Maschuta, a continuous increase in burials and the construction of round above-ground silos can be seen. The graves showed marked differences in terms of the status of the buried people. Warriors' burials contained the Asian style weapons typical of that time, such as daggers and chisel-shaped axes . The other mud brick graves contained numerous valuable grave goods such as headbands made of gold or silver as well as bracelets decorated with silver, earrings and hair rings, gold and silver scarabs , tools and semi-precious stones , as well as amulets and food. Children's graves and burials in the disused round silos, on the other hand, contained only a few grave goods.

On the basis of the paleobotanical findings, the archaeological team of the Wadi Tumilat project drew the conclusion that Tell el-Maschuta fulfilled all the criteria of an urban settlement, but was only inhabited seasonally from the beginning of the sowing in autumn until the end of the summer wheat harvest in spring . Because of these features, Tell el-Maschuta had the character of a caravan station set up for long-distance trade. Tell el-Maschuta remained uninhabited during the hot summer months. The inhabitants probably settled in the vicinity of Tell er-Retaba , where housing camps existed in the Middle Bronze Age . The materials used for the construction of Tell el-Maschuta show parallels to the finds in Straten E1 to D3 by Auaris . Residential houses were built with ever closer distances to each other. The extent of agriculture , especially wheat and barley cultivation to supply the residents, increased sharply. In addition, were cattle , sheep , goats and pigs kept. The horse breeding was already known. The residents also hunted various species of birds, hartebeest and gazelles .

The workers employed in agriculture were also used for other activities, for example in the craft with pottery and for the production of bronze tools . In addition, looms were used, clothes were made and sickles with prefabricated blades were used. The exact purpose of the high-temperature furnaces found during the excavations is unclear. In an industrial process, ocher-colored stakes were driven into the ground. The ovens may have been needed to make leather with metal fittings, as well as anvils or grinders. The final examination of the found pottery revealed that after the Hyksos were driven out by Kamose and Ahmose I, the settlement fell into disrepair and remained uninhabited for at least the period from the New Kingdom to the end of the Third Intermediate Period (1550 to 652 BC).

Second settlement phase

String dynasty from Necho II. (610-525 BC)

Tell el-Maschuta was not used again until the end of the 7th century BC. Newly founded not far from Tell er-Retaba . During this time, Necho II. Between 610 and 605 BC. Create the Bubastis Canal to connect the Pelusian arm of the Nile to the Red Sea . The new canal ran through Wadi Tumilat and Egypt promised strategic and agricultural advantages from it.

The newly created site of Tell el-Maschuta initially served as a warehouse for the workers involved in building the canal. A short time later, Apis bulls were sacrificed there and facilities were built for the later temple, House of Atum . Houses, barns and ovens were built north of the temple. In the midst of this building phase, sudden changes can be seen, which are probably due to Nechos' Karkemisch defeat in 605 BC. And the loss of its sovereignty in Retjenu . Shortly thereafter, a fortification wall about nine meters wide was built around Tell el-Maschuta, enclosing an area of 200 m × 200 m. Settlement came to a standstill, however, as the protected area was not used for further building of houses during the Saitic dynasty.

The community on a four hectare area was 601 BC. And destroyed for the second time 15 years later. Previously, the attempt of the Egyptian pharaoh Apries in association with Zedekiah to prevent the capture of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II had failed . The devastation can thus be attributed to the Babylonian king. In Tell el-Maschuta two pieces of Jewish ceramic from the year 568 BC were found. Found that a presence of Jewish refugees around 582 BC. In Tell el-Maschuta attest. Larger quantities of similar ceramic ware appeared in Tahpanhes , which is about 22 km away from the mouth of the Pelusian arm of the Nile , and in a place in the western Sinai region that has been provisionally identified as Migdol .

Map of Egypt |

After the destruction and reconstruction, Tell el-Maschuta developed during the String Dynasty under the pharaohs Apries, Amasis and Psammetich III. a highly frequented trading place. The reason for this may have been the central location between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea as well as the trade connection to the Indian Ocean , especially since Tell-el Maschuta was about halfway between Suez and Bubastis . The archaeologically proven large quantities of Phoenician merchandise coincide with the statement by Herodotus that numerous Phoenicians settled in a "Phoenician camp near Memphis " during the reign of Apries :

“Then the kingdom came to a man in Memphis, in the language of the Hellenes called Proteus . He now has a sanctuary in Memphis, which is very beautiful and well furnished and is located after noon by the Temple of Hephaestus . Around this sanctuary live the Phoenicians of Tire and this whole place is called 'Camp of the Tyrians'. "

The Phoenician trade, which increased in size through the use of the Bubastis Canal, is documented by numerous finds of Phoenician amphorae in Tell el-Maschuta. The amphorae served as storage containers for the merchandise. As further evidence is considered one in the ruins of a limestone - shrine salvaged terracotta statue, as seated goddess probably Tanit or Ashera embodies. Greek amphorae were represented in smaller numbers , mostly from Thasos or Chios . There were also imported thick-walled mortars and the associated pestles , which are probably of Anatolian origin.

First Persian dynasty from Cambyses (525–404 BC)

With the conquest of Egypt in 525 BC BC by Cambyses II was accompanied by another destruction of Tell el-Maschuta at the battle of Pelusion . In the following period, the construction work on the site is well documented. The settlement area, which was expanded during the Saiten Dynasty, was used for new buildings during the Persian period with an expansion in the southwestern area. In the northern part of Tell el-Maschuta, an area was uncovered that was used in Persian times from the end of the 6th century BC. Until about 404 BC Served as a necropolis south of the temple area on the Bubastis Canal .

Darius I expanded the Bubastis Canal to a total length of 84 kilometers after he came to power. On four large steles , the first of which was in Tell el-Maschuta, Darius I had his achievements written down in the languages Egyptian , Old Persian , Elamite and Akkadian . In the course of 487 BC When the Egyptian rebellion against the Persians began in the 4th century, another stone wall was built outside the city wall of Tell el-Maschuta, which was filled with rubble, ceramics and other materials. The archaeological evidence confirms the battles for Tell el-Maschuta associated with the rebellion. In the period that followed, new warehouses were built in the entire local area. After 404 BC The Persians were driven out of Egypt until about 379 BC. Uninhabited.

The last independent ancient Egyptian dynasty (379–341 BC)

Fragments of monuments of the 30th dynasty testify to the enormous building program of the pharaohs Nectanebos I and Nectanebos II , which, in addition to promoting the ancient Egyptian religion, brought about a short-term " renaissance " for Tell el-Maschuta as well. With the resettlement, trade and imports of goods skyrocketed during the 30th Dynasty, although the Bubastis Canal slowly silted up .

The trade revived by the Phoenicians mainly focused on wine , olive oil , fish sauces, and other long-life foods . More distant regions such as Thasos, Chios and Anatolia also participated in the exchange of goods, as did Arabia and Athens in particular . The temple cult of the Egyptian god Atum experienced a renewed heyday, as demonstrated by the cube-shaped altars made with South Arabian influence. The existing ink inscriptions on pieces of glass were mostly written in demotic script . The use of incense , which was also imported from southern Arabia, is documented as part of the sacrifices for the Atum Temple .

The accidental discovery of a camp containing thousands of Athenian tetradrachms caused a particular stir . The exceptionally high amount refers to donations as gifts to the Atum temple. In addition, four bowls were discovered whose style and design suggest a Persian origin and probably reached Tell el-Maschuta via southern Arabia. All four dishes wore similar inscriptions, taking on one of the shells of Aramaic entry " What Qaynu, son of Gaschmu , King of Qedar for Han'Ilat offered up " can be read. Maybe this is gashmu. identical to the figure of the same name in the book of Nehemiah of the Old Testament . The inscriptions on the bowls and additional silver coins found , which show the owl of Athena on their reverse , are dated to the transition from the fifth to the fourth century BC. Dated. The end of the 31st dynasty , which was replaced by Alexander's conquest of Egypt, caused the inhabitants of Tell el-Maschuta to emigrate, which was a period without settlement until around 285 BC. Followed.

Reconstruction of the Atum temple and construction of trading houses (285 BC to 1st century BC)

Pharaoh Ptolemy II (285 to 246 BC) began after taking over his rule with the desanding and renewal of the Bubastis Canal, which was connected with a modernization program for Tell el-Maschuta. Due to the extensive construction work, the place developed again into an important trading post. The Pharaoh had his project inscribed and celebrated on a stele that Ptolemy II erected in Tell el-Maschuta.

For the reconstruction of the Atum temple, numerous larger limestone blocks were transported from other places in Egypt to Tell el-Maschuta. A two-room building that had already collapsed from the Persian period was used as a pottery after reconstruction . In addition, towards the end of Ptolemy II's reign, there were probably up to six-room granaries or multi-room warehouses on the banks of the Bubastis Canal, to which several melting furnaces for the production of bronze goods for the Atum Temple and export were connected.

The trading houses and warehouses discovered by Édouard Naville and assigned to the “Children of Israel” probably date from the early days of the building program under Ptolemy II, since only these were in direct proximity to the melting furnaces on the banks of the Bubastis Canal. Ptolemy III (246 to 222 BC) and his successors must have initiated further extensive construction work by trading houses and workshops, as the Wadi Tumilat project was only able to excavate a small number of the numerous and sometimes up to 75 m long trading houses in its campaigns . The trading houses researched so far could be based on the period between the second half of the 3rd century BC. Until about 125 BC To be dated. After the end of the Ptolemaic rule, Tell el-Maschuta experienced a decline, so that the place at the beginning of the 1st century BC. BC lost its main function as a trading post and was therefore abandoned again by the residents.

Tell el-Maschuta as a Roman necropolis

After the residents of Tell el-Maschuta at the beginning of the 1st century BC Had left, the facilities fell into disrepair. The place remained unused until the beginning of the 2nd century AD. When Trajan again expanded the Bubastis Canal after taking office , the region of Tell el-Maschuta functioned as a Roman necropolis and experienced the largest expansion in area since it was founded under the Hyksos . A new settlement did not take place, however, as numerous graves were built on the ruins of the former trading place. Earlier smaller excavation campaigns had already partially uncovered the Roman cemetery, which is why the archaeological team from Toronto did not conduct any further intensive investigations at this point, but was able to confirm the large quantities of ceramic finds in the uppermost strate.

The findings showed that the necropolis was mostly laid out for “ privileged Roman citizens” from square underground graves and was provided with vaulted superstructures. These mud brick grave complexes each had an additional access path or walled dromos , which made it possible to enter the grave rooms on the east side of the graves. The vaulted grave entrances, which had only one easy access route, were bricked up after each burial. On the other hand, the relatives of the grave owner filled the dromos burial passage with sand. Gold-coated figures of gods, earrings, glass vessels and hairpins made of bone served as grave goods . During the active use as a necropolis, the valuable grave goods were partially looted .

There were also simple burials that were embedded in the free space between the mud-brick graves without any special additions of statuettes . The majority of the burials had the characteristic forms of the Roman style, which is also visible in the symbolic alignment of the graves. The necropolis also had a burial area for children. A Christian child funeral is noteworthy in this context . In the upper part one from Gaza coming amphora , a was Coptic inscription , the two " Chi-Rho symbol " as Christ monogram was provided that n since the second century. AD. Christians used to represent their faith and to be to recognize each other. However, this form of burial was only found in very few grave goods.

In the early 4th century AD, Tell el-Maschuta was abandoned as a Roman necropolis, which is evidenced by the lack of ornate grave lighting. Around 381 AD the existence of a Roman " garrison of heroes" stationed in the region of Tell el-Maschuta is attested, but at that time it was relocated to Abu Suwerr , only about two kilometers away , and its military function preserved and so today houses a military airfield .

Identifications with the biblical pitom or sukkot

For a long time, controversial discussions have been held about the question of whether Tell el-Maschuta can be identified with the Old Testament Pitom or Sukkot . Édouard Naville saw his archaeological findings confirmed that it was the "Children of Israel " who built the "trading houses" in Tell el-Maschuta. Kenneth Anderson Kitchen , on the other hand, considers Tell el-Maschuta to be the biblical Sukkot, at which the Israelites camped when they left Egypt . Kitchen still stands by his hypothesis that both Tell er-Retaba and Tell el-Maschuta coexisted as settlements in the New Kingdom , without taking into account the ceramic findings of the archaeological team of John S. Holladay. Donald B. Redford , on the other hand, followed Holladay's results and sees Tell el-Maschuta as the biblical Pitom, which, however, was only built 600 years after the exodus from Egypt.

The references to Sukkot in the Pentateuch ( Ex 12.37 EU , Num 33.5–6 EU ) remain unclear and leave open whether it is a city, a village, a fort or a region. The “construction of the city of Pitom” mentioned in Ex 1.11 EU can hardly be reconciled with the past of Tell el-Maschuta. Against the background of the excavations, those historians who assessed the story of the Exodus from Egypt as a fiction or saw it as an anachronistic supplementary report, which did not appear until the 6th century BC , felt encouraged . Was recorded in the scriptures.

Exact examinations of the ancient Egyptian papyri show that the name “Tjeku / Tscheku”, from which the Hebrew equivalent “Sukkot” is derived, almost always referred to a larger area in the 19th and 20th dynasties and only once with the city determinative

|

literature

- Hans Bonnet : Pithom. In: Lexicon of Egyptian Religious History. Nikol, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-937872-08-6 , p. 596.

- William J. Dumbrell: The Tell-el-Maskhuta Bowls and the "Kingdom" of Qedar in the Persian Period. In: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR). No. 203. American Schools of Oriental Research, Baltimore 1971, pp. 33-44.

- James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-515546-7 .

- John S. Holladay: Pithom. In: Donald B. Redford: The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt. Volume 3: P-Z. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-19-513823-6 , pp. 50-53.

- John S. Holladay: Tell el-Maskhuta. In: Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt . Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 786-789.

- John S. Holladay: Tell el-Maskhuta: Preliminary report on the Wadi Tumilat Project 1978-1979. Undena Publications, Malibu 1982, ISBN 0-89003-084-7 .

- Édouard Naville: The store-city of Pithom and The route of the Exodus. Trübner, London 1903, online (first published in 1888) .

- Eliezer Oren: Migdol: A new fortress on the edge of the Eastern Nile Delta. In: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR). No. 256. American Schools of Oriental Research, Baltimore 1984, pp. 7-44.

- Patricia Paice: A preliminary analysis of some elements of the Saite and Persian period pottery at Tell el-Maskhuta. In: Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar (BES). No. 8th Seminar, New York 1987, pp. 95-107.

- John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. In: John Andrew Dearman: The land that I will show you: Essays on the History and Archeology of the Ancient near East in Honor of J. Maxwell Miller. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield 2001, ISBN 1-84127-257-4 , pp. 255-276.

Web links

- Granite statue of Ankh-chered-nefer from Tell el-Maschuta

- wibilex: Technical article “Pitom” by Karl Jansen-Winkeln

Individual evidence

- ↑ Instead of the hieroglyphs U15, Aa15 and X1 the god Atum can be seen in the original, who is depicted with a double crown and scepter. The illustration of this hieroglyph cannot currently be represented in the Wikipedia font, hence the representation in the otherwise used hieroglyphs; Place name "Pi-Tem" and other hieroglyphs according to Édouard Naville: The store-city of Pithom and The route of the Exodus. P. 5.

- ↑ Herodotus Historien , II 158; John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. P. 273.

- ↑ a b c d James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Autenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. P. 62.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Autenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. P. 61; John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. P. 273.

- ^ NYPL Digital Gallery: Monoliths d'Abou-Keycheyd (1847) .

- ^ A b Édouard Naville: The Store-city of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus . London, 1885, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Edouard Naville: The Store-city of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus . London, 1885, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. Pp. 256-257.

- ↑ a b c d James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Autenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. P. 59.

- ^ Excavations of the Wadi Tumilat project .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k John S. Holladay: Tell el-Maskhuta. In: Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt. P. 787.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i John S. Holladay: Tell el-Maskhuta. In: Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt. P. 788.

- ^ Isaac Rabinowitz: Aramaic Inscription of the Fifth Century BCE from A North-Arab Shrine in Egypt. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies No. 15, 1956, pp. 1-9.

- ↑ Nehemiah 2:19 and 6: 1-6.

- ^ Walter C. Kaiser: A history of Israel: From the bronze age through the Jewish Wars - The Returns under Ezra and Nehemia (chap. 28) . Broadman & Holman Publications, Nashville 1998, ISBN 0-8054-6284-8 , p. 19; David Janzen: Witch-hunts, purity and social boundaries: The Expulsion of the foreign women in Ezra 9-10 . Sheffield Press, London 2002, ISBN 1-84127-292-2 , p. 139.

- ↑ John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus . P. 262.

- ^ A b John S. Holladay: Tell el-Maskhuta. In: Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt. P. 786.

- ↑ a b c d John S. Holladay: Tell el-Maskhuta. In: Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt. P. 789.

- ↑ Kenneth Anderson Kitchen: Ramesside Inscriptions, Translations: Merenptah and the Late Nineteenth Century. Blackwell Publications, 2003, ISBN 0-631-18429-5 , pp. 256-259 and 555.

- ^ Barry J. Kemp: Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a civilization - Who were the ancient Egyptians? - The intellectual foundations of the early state - The dynamics of culture - The bureaucratic mind - Model communities - New Kingdom Egypt: The mature state - The birth of economic man - Moving on - . Routledge, London 2006, ISBN 0-415-23549-9 , pp. 290-291.

- ↑ John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. P. 270.

- ^ Alan Gardiner: The Delta Residence of the Ramessides. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology (JEA) 5. Egypt Exploration Society, London 1918, pp. 268-269; John van Seters: The Geography of the Exodus. P. 262.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Autenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. P. 64.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier: Ancient Israel in Sinai. The Evidence for the Autenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Pp. 63-64; Karl Jansen-Winkeln: Pitom. In: "Pitom". wibilex 2007 .

Coordinates: 30 ° 33 '10 " N , 32 ° 5' 58" E