Hodegetria

The Madonna Hodegetria or Hodigitria or Odigitria ( ancient Greek ὁδηγήτρια "Wegweiserin" in classical Greek unknown feminine shape to ancient Greek ὁδηγητήρ hodegeter "guide, teacher", formed from ancient Greek ὁδός hodos "way" and ancient Greek ἡγεῖσθαι hegeisthai 'lead, go ahead ") - also known as Theotokos (" Theotokos "), Panagia (the "All Saints"), Platytera ("Our Lady of the Sign"), Nicopoia (the "Victory Bringer"), Eleusa (the "Merciful"), Glykophilusa (the "Caressing") or also Madonna of Constantinople - denotes a certain type of depictions of Mary , which was first to be found on Greek-Byzantine icons before iconoclasm, mainly in Constantinople . The type had an enormous influence on Christian art and spread in copies in the medieval world not only in countries with Orthodox rite from Greece to Russia , but also in China , Ethiopia and Italy , so that icons of Mary and later other images in this Type among the believers are considered to be the "most sublime representation of the Mother of God".

origin of the name

The term Hodegetria dates back to the Greek word hodigoi ( "leader," Sing. : Hodegos or odegos ) back which monks ( Calogeri called), the blind pilgrims to a wonderful strong source ( Zoodochos Pigi ) accompanied a sanctuary in Constantinople Opel. In the course of time the name of the Mother of God and her icon was given in the feminine form hodegetria ; for some based on the guides for the blind, for others based on the road ( ancient Greek ὁδός odos ) that led to the place of pilgrimage.

origin

When the former Greek colony of Byzantium was rebuilt by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great in 324 AD and made the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire in 330 AD under the name of Constantinople , there were no important religious figures who could have represented the city . The personality cult of Byzantine worship was mostly imported from the west of the Roman Empire and adopted passively.

In the first centuries of Christianity there was a fundamental difference in behavior between the two parts of the Roman Empire in relation to religion and the cult of personalities, which became increasingly evident.

In early Christian art there was no specific iconography of Mary because everything related to Christ and consequently the depiction of the Virgin carrying the baby Jesus fell into this perspective. The Virgin Mary, painted on the walls of the catacombs , occupied a humble but indispensable place as Mother of Christ, reinforced by the councils of Ephesus in 431 and Chalcedon in 451.

In the union formula of Ephesus of 433 Mary was recognized as the bearer of God (Theotokos). This led to a real cult around the veneration of Mary . Constantinople was the city protected by God and the Theotokos, and the Byzantine Empire was created by the will of God and the Theotokos.

Aelia Eudocia , wife of the Eastern Roman emperor Theodosius II , is said to have brought relics to Constantinople from her pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 438/439 . Among them should have been a miraculous image, the veil (Maphorion) and the belt (zone) of the Blessed Mother, which Aelia Eudocia later sent to her sister-in-law Aelia Pulcheria . The cult image of Hodegetria is said to have consisted of the head of the Madonna with the child, which is said to have been painted in Palestine by the evangelist Luke on a wooden panel using the encaustic technique. The cult image is said to have been supplemented in its iconography in Constantinople . The head of the Blessed Mother became an icon with the whole figure of Mary.

After the death of Theodosius II in 450, his older sister Aelia Pulcheria is said to have built three churches dedicated to the Mother of God in various districts of Constantinople:

- The first and most important church was the one near the church of the Hodigoi ("Führer", Sing . : hodegos or odegos ). east or south-east of Hagia Sophia , in which the cult image of the Mother of God is said to have been kept and venerated. The church and the monastery were given the name Hodegon , the cult image that of the Hodegetria . The name Hodegetria was later given an additional meaning due to Maria's arm-hand posture, whose fingers point to the son as “way, truth and life”. The famous image was considered the protector of the city of Constantinople and the whole Eastern Empire. The Byzantine emperors themselves are said to have carried them at the head of their triumphant processions as “signposts” and in this way affirmed the title of Hodegetria . Owning them was very important and meant the true Palladium of Constantinople. The icon of Hodegetria is said to have been destroyed with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire (1453). However, the type of representation has been preserved through copies of the original.

- This was followed in the Chalkoprateia district ( ancient Greek Χαλκοπρατεῖα , copper market) 150 meters west of Hagia Sophia, the Chalkoprateia church , in which the belt of the Blessed Virgin was kept and venerated. Infertile and pregnant women and women in labor turned to the “holy belt”. The Zeynep Sultan Mosque now stands on the site of the Chalkoprateia Church .

- In 452, Empress Aelia Pulcheria had the Blachernenkirche built on the land wall of the Golden Horn , an important point in the north for the defense of the city, in the district of Blachernae , in order to keep Mary's dress and her shawls, which were found in the empty tomb after her death to worship. In special moments of danger one turned to the veil.

- It is reported that Emperor Michael III , who hastily returned from his campaign against the Arabs . and the Patriarch Photios I, after a solemn procession to the Golden Horn, threw the veil of Our Lady Mary into the sea on June 18, 860, whereupon the enemies ( Rus ) broke off their siege and sailed away.

The Church of St. Mary of Blachernae also had other images of the Virgin, a Deësis , a Hodegetria, which were also called Blacherniotissa or "praying Mary" (Latin Maria orans ). The Church of St. Mary of Blachernae burned down in 1433 and the icon Blachernae, which was considered the original prototype, was destroyed in the process.

Apparitions of Mary in Constantinople

There are five known apparitions of Mary , recognized by both the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church in the ancient capital of Constantinople.

- In 455 Maria appeared to the later Byzantine Emperor Leo I , who in 473 had a new church built near the Blachernen Church built by Pulcheria in 452, to which he named Saint Maria von Blachernae .

- In 522, Mary appeared to a Hebrew boy to save him from the cruelty of his father.

- In 714 Mary appeared to the mother of the later monk Stephanos the Younger , who resisted the iconoclast Emperor Constantine V.

- In 1325 Mary appeared to Abbot Gerontius, who had appropriated an icon of the Most Holy Mother of God in order to become Metropolitan of Russia , and persuaded him to return it.

Iconographic story

The Marian icons are the most numerous in iconography and are the ones most loved by the faithful. The Madonna is mainly shown as a half-length portrait , but also sitting or standing as a full-body portrait. Obligatory it is painted on a gold background, symbol of heaven where it is. She holds the Divine Son either on her left arm (sometimes on the right) or on her lap. Jesus has the stature of a child and the features of an adult. His robe is often illuminated by golden reflections. This seemingly unusual staging suggests that he, Immanuel (עִמָּנוּ אֵל “God (is / be) with us”), is the Son of God and God himself. Mary's divine motherhood is attested by two abbreviations on both sides of the head: "MP ΘY", for "Μητέρα του Θεού" (Mother of God).

Historically there are no contemporary representations of the Mother of God and soon the search for the archetype began. There are several historical testimonies, all of which give a different description.

There is a description by Georgios Kedrenos , Byzantine historian from the 11th and 12th centuries. After him, Maria was short in stature with dark skin, blond hair, with light and small eyes, marked eyebrows, a small nose and narrow fingers.

The Greek church historian Nikephoros Kallistu Xanthopulos (* around 1268/1274; † after 1328) takes up the texts of his predecessors on the somatic traits of Mary again in his Historia ecclesiastica and confirms the statements of the priest Epiphanius from the 8th / 9th centuries. Century that she was of medium stature and with the skin color gilded by the sun of the fatherland (the color of wheat), that she had blonde hair, a sharp look, somewhat bluish eyes with olive-colored pupils, curved black eyebrows, an elongated nose and red Had lips. The face was neither round nor angular, but elongated. Her hands and fingers were narrow. It is said that she preferred dresses of natural colors, as evidenced by her head veil, which has been kept in the Church of Saint Mary of Blachernae.

From the handbook of painting by the Greek painter monk Dionysios of Phourna (* around 1670, † after 1744) one reads the following picture about the "Character of the Theotokos":

“The Most Holy Mother of God (is) in middle age; others also say it is three cubits; wheat colored; yellow-haired with yellow eyes, beautiful hair, large eyebrows, medium nose, long hand; long fingers; beautiful dresses; humble, inconspicuous, not careless (in dress); loves natural colors on clothes; this is attested by the homophorium that lies in their temple. "

As already mentioned, there are no contemporary depictions of the Mother of God, which has led artists over the centuries to let their imaginations run wild. There are around 400 different icons of the Blessed Mother. Originally, however, there were mainly three different iconographies:

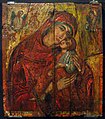

- the Hodegetria ( Greek Οδηγήτρια , signpost and patroness of Sicily and the wanderer). The Mother of God is depicted in a static, rigid and frontal position and holds on her left arm (Aristerokratusa), sometimes also on the right (Dexiokratusa), the no longer childlike, blessing Child Jesus , who often holds a scroll in her left hand. With the fingers of her right hand Mary points to the child, to the "path" of redemption . Jesus makes a rather transfigured expression, Mary radiates dignity. A variant of the Hodigetria are Eleusa , the "merciful" and Glykophilusa , the "caressing". The difference between the Eleusa and the Glykophilousa is not clear and lies in the intensity of the display of affection between the mother and her son. The Blessed Mother holds her child tenderly in her arms, Jesus hugs his cheek against his mother's. According to some scholars, the child in this icon touches the Virgin's chin with his hand.

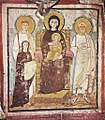

- The Blacherniotissa or praying Madonna goes back to three images of grace in the Blachernenkirche and is standing and praying with arms raised to the side ( Orantenpose ) without the Child Jesus or with the full or half-length Child Jesus in the form of a breast medallion at the height of the belly ( Blacherniotissa Platytera ; Greek: platys, “wide”, “wide”). Another form of Blacherniotissa is the depiction of Mary, with or without baby Jesus, flanked by saints and angels ( Panagia , Greek: "Most Holy").

- The Nicopoia (the "victory-bringing"; also: Nikopea , Nikopeia , Nicopeia ) or the Madonna Enthroned ; the Mother of God, seated on the throne, holds the baby Jesus on her lap in front of her breast. This representation is the most commonly used in the Christian world.

Modern icon of Hodegetria in the Greco-Byzantine Chiesa San Basilio Magno in Ejanina

Icon of Glykophilusa from 1547 ( Musée d'art et d'histoire in Geneva )

Fresco of the Blacherniotissa Orantenpose from the 13th century in the Theotokos Peribleptos Church in Ohrid in Macedonia

Nicopeia, fresco in the Commodilla Catacombs in Rome, 528

According to tradition, the icons of Mary reproduce an original portrait of Mary, which the Evangelist Luke is said to have painted on a wooden panel (icon) after Pentecost , when Mary was still living in Jerusalem . In the 5th century the portrait is said to have been brought to Constantinople and kept in the Marian sanctuary Hodegetria, from which the picture is said to have been named later ( see above ). This explains why many icons of Mary in Italy are venerated as the Madonna of San Luca, Greek Madonna, Madonna of Constantinople or Madonna Odigitria. The latter is also abbreviated as Madonna d'Itria (also: dell'Itria, dell'Idria). After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the icon is lost. The appearance of the Madonna can be deduced from the countless replicas, since she was probably the most reproduced icon.

It should be mentioned that Italian art has remained true to the model for many centuries, which is evident in many Madonnas in Florence , Naples, Sicily and Venice from the 13th / 14th centuries. Century can be observed.

The Renaissance (mid-14th - end of the 16th century) marked a task for this art. In their place came the art of the so-called "Madonnari" (Madonna painter, street artist ), who immortalized the memory of the Madonna Hodegitria in Venice and in the neighboring regions.

Succession

Hodegetria as a type of depictions of Mary found numerous successors to the original icon, both in the Eastern and Western churches .

A mirror-image copy of the cult image of Mary is said to have been made on canvas in Constantinople, so that the child was on the right arm of the Madonna (Dexiokratusa). Aelia Eudocia would have given this copy to the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III between 439 and 440 . and his wife Licinia Eudoxia to Ravenna, who personally brought the cult image to Rome, where it was kept in the imperial palace complex Domus Augustana on the Palatine Hill . Later it was brought to the nearby Chiesa Santa Maria Antiqua at the foot of the Palatine Hill, where the Madonna was copied in one of the frescoes . From here the cult image is said to have been brought to the Chiesa Santa Maria Nova (today: Santa Francesca Romana ). The " Salus populi Romani " is said to have originated from this picture , which is also attributed to Saint Luke and is venerated in the Cappella Paolina in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore .

Among the famous replicas of the type revered in Italy are

- the icon of the Madonna Consolata (the Consoling One) in the Santuario della Consolata in Turin

- the icon of the Madonna Mesopanditissa (Mediator of Peace) or Madonna della Salute (Madonna of Health) in the Basilica della Salute in Venice

- the icon of the Madonna di San Luca (from Saint Luke) in the Santuario della Madonna di San Luca in Bologna

- the icons of the Madonnas Hodegetria in the crypt Santa Maria di Costantinopoli in the Cathedral di San Sabino in Bari , Apulia and in the Cathedral of San Demetrio Megalomartire di Tessalonica in Piana degli Albanesi , Sicily from the 16th century

- the fresco of the Madonna Achiropita (considered as "not made by human hands") in the Cathedral di Maria Santissima Achiropita in Rossano , Calabria , etc.

Madonna Mesopanditissa in the Basilica della Salute in Venice

Rome has no fewer than ten such icons.

- The oldest from the 5th / 6th Century, the Madonna del Conforto or Santa Maria Nova is kept in the Basilica of Santa Francesca Romana .

- The icon of the Madonna Hodegetria of the Pantheon is from the 7th century

- Fresco of the enthroned Madonna in Cosmedin in the Melkite Greek Catholic basilica of the same name near the bank of the Tiber in Piazza Bocca della Verità from the 12th century

- The icon of the Madonna della Salute (Health) in the Basilica dei Santi Cosma e Damiano from the 12th century

- The icon of the Madonna del Rosario (Virgin Mary of the Rosary) in the 15th century Basilica di Santa Maria sopra Minerva , attributed to Fra Angelico

- The fresco of the Madonna, called del Bessarione, in the Bessarion Chapel in the Basilica dei Santi XII Apostoli from the 15th century.

Even if it is not possible to give the exact date, it is worth mentioning

- the icon of the Madonna of Constantinople, icon of the high altar in the Basilica of Sant'Agostino in Campo Marzio

- the Madonna d'Itria in the Chiesa Santa Maria d'Itria

- the Santa Maria dei Miracoli in the Chiesa di San Giacomo in Augusta

- the icon of Madonna Odighitria in the Chiesa del Santissimo Nome di Maria al Foro Traiano u. at the

Among the well-known representations in Europe that are still called pilgrimage sites today

- the icon of Our Lady of the Gate in the Iviron Orthodox Monastery on Mount Athos in Greece

- the icon of Our Lady of Smolensk in Smolensk in Russia, painted by Dionisius (1444 - ca.1502)

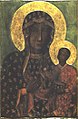

- the miraculous image of the Black Madonna of Czestochowa in the pilgrimage site of Częstochowa in Poland

Modifications

- The Kazan Mother of God also corresponds to the Hodegetria type , but is only designed as a head image, so that the right hand of the Madonna is not shown.

- In Byzantine mosaics in Italy, such as the Basilica of Torcello in Venice, the image of a standing Hodegetria is sometimes represented.

Hodegetria icons in Italy

Hodegetria icons are to be found in Italy both in the Greek-Byzantine churches of the Arbëresh in Abruzzo , in Basilicata , Calabria and in Sicily, as well as in Roman Catholic churches.

Greco-Byzantine churches

- Chiesa Santa Maria Assunta in Villa Badessa

Icon of Hodegetria in the chancel ( Bema ) in the Chiesa Santa Maria Assunta in Villa Badessa

Icon of the Hodegetria in the Chiesa Santa Maria Assunta in Frascineto

Icon of the Hodegetria in the Chiesa San Basilio Magno in Ejanina

Icon of the Hodegetria in the Chiesa Santissimo Salvatore in Cosenza

Icon of the Glykophilousa (the "Caressing") in the Chiesa Santa Maria Assunta in Civita

Icon of the Hodegetria (Dexiokratusa) in the Chiesa San Costantino il Grande in San Costantino Albanese

Roman Catholic churches

- Chiesa della Madonna di Loreto in Villalago , Abruzzo

- Abbazia di Santa Maria di Pulsano (Monte Sant'Angelo) in Monte Sant'Angelo in the province of Foggia

- Chiesa Madonna di Loreto (Torremaggiore) in Torremaggiore in the province of Foggia

- Concattedrale di Sant'Eustachio (Acquaviva delle Fonti) in Acquaviva delle Fonti in the province of Bari

- Cappella Madonna di Costantinopoli in the Chiesa Santa Maria Assunta in Binetto in the province of Bari

- Chiesa dell'Immacolata (Novoli) in Novoli in the province of Lecce

Hodegetria icon in the Chiesa della Madonna di Loreto in Villalago

Hodegetriakirchen

The Hodegetria are consecrated u. a. the churches

- Chiesa di Santa Maria Odigitria in Rome

- Hodegetria Church (Mistra)

- Hodegetria Church (Vyasma)

- Hodegetria Church (Constantinople)

literature

- Peter W. Hartmann: Art Lexicon . Beyars GmbH, Neumarkt 1996, ISBN 978-3-9500612-0-8 ( beyars.com ).

- Gaetano Passarelli: Le icone e le radici. Le icone di Villa Badessa . Fabiani Industria Poligrafica, Sambuceto 2006 (Italian).

- Alfredo Tradigo: Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church (Guide to Imagery) . Getty Trust Publications, Los Angeles 2008, ISBN 978-0-89236-845-7 , pp. 163 ff . (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ The Church of the Hodigoi was so named because it was located near a monastery where the guides (monks) lived, who accompanied those suffering from eye diseases (mostly the blind) to the miraculous spring not far away, where they were expected would get their eyesight back.

Individual evidence

- ^ Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church, p. 163

- ↑ Odigitria. In: Treccani.it. Retrieved July 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Alfredo Tradigo: Picture Dictionary of Art / icons and saints of the Eastern Church: Picture Dictionary of Art . tape 9 . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-936324-05-1 , pp. 169 .

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin: L'iconografia dell'immagine della madonna . Storia e Letteratura, Rome 2005, ISBN 88-8498-155-7 , p. 8 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c d Michele Scaringella: La Madonna Odigitria o Maria Santissima di Costantinopoli e San Nicola venerati a Bari. (PDF) p. 5 , accessed on July 5, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin, p. 7

- ↑ Sercan Yandım: The icons from the museums in Antalya and Tokat in Turkey . VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, Saarbrücken 2008, p. 52 .

- ↑ Gigi Montenegro: Origine del titolo mariano di Madonna di Costantinopoli: il mistero di Montevergine. (PDF) In: Lavesterossa.com. P. 4 , accessed on July 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Origine del titolo mariano di Madonna di Costantinopoli: il mistero di Montevergine, p. 5

- ^ Ernest Mamboury , Robert Demangel: Le Quartier des Manganes et la premiere region de Constantinople . E. de Boccard, Paris 1939, p. 71 ff . (French).

- ↑ Origine del titolo mariano di Madonna di Costantinopoli: il mistero di Montevergine, p. 2

- ↑ Michele Scaringella: La Madonna Odigitria o Maria Santissima di Costantinopoli e San Nicola venerati a Bari. (PDF) p. 6 , accessed on July 25, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Church of St Mary Chalkoprateia Istanbul. In: Veryturkey.com. Retrieved June 9, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Patrizia Morelli, Silverio Saulle: Anna Comnena: la poetessa epica (c. 1083-c. 1148-1153) . Jaca Book SpA, Milan 1998, ISBN 88-16-43506-2 , pp. 27 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Quel capolavoro di Dio. In: Stpauls.it. Retrieved July 30, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Ingeborg Bauer, p. 70

- ↑ Mary. Heiligenlexikon.de, accessed on June 9, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ On the basics of composition: The Icon and the Akathistos - Hymnos. (PDF) In: Ulrichgasser.ch. P. 2 , accessed August 1, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Georges Gharib: Testi mariani del primo millennio . tape 2 . Città Nuova, Rome 1988, ISBN 978-88-311-9216-3 , p. 845 ff . (Italian, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin, p. 41

- ↑ Marian apparitions. Heiligenlexikon.de, accessed on June 11, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d e Le icone della Madre di Dio. In: Latheotokos.it. Retrieved August 2, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Meter Theou. In: Beyars.com. Retrieved August 2, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin, p. 38

- ↑ Dionysius of Phourna: The manual of painting from Mount Athos . Lintz, Trier 1855, p. 418 .

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin, p. 5

- ↑ Our Lady icons. In: Orthodoxicon.eu. Retrieved July 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Glycophilousa. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 27, 2018 ; Retrieved August 1, 2017 (Italian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Eleousa. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 27, 2018 ; Retrieved August 1, 2017 (Italian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin: L'iconografia dell'immagine della madonna . Storia e Letteratura, Rome 2005, ISBN 88-8498-155-7 , p. 113 (Italian, online version (preview) in Google Book search).

- ↑ Blacherniotissa. In: Beyars.com. Retrieved July 30, 2017 .

- ^ Hans Belting: Image and cult: a history of the image before the age of art . CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-406-37768-6 , pp. 87 ( online version (preview) in Google Book search).

- ↑ Michele Scaringella: La Madonna Odigitria o Maria Santissima di Costantinopoli e San Nicola venerati a Bari. (PDF) p. 5 , accessed on July 5, 2017 (Italian).