Judaism in Regensburg

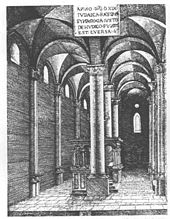

Etching by Albrecht Altdorfer

The history of the Jews in Regensburg goes back to the 10th century. Today (2013) the Jewish community in Regensburg has more than 1000 members.

middle Ages

A fully structured community already existed in Regensburg around the year 1000; it had a synagogue , a school, a civil court and a cemetery in the Argle forest near Großberg . The monk Arnold von Vohburg reports on a Jewish-Christian dialogue around 1130.

Center of Jewish learning

Around 1080 the famous rabbi , Talmudic scholar and poet Menachem ben Mekhir lived in the city . In connection with the First Crusade , the Regensburg Jewish community was forcibly baptized in 1096 , but was allowed to return to its original religion the following year due to a privilege granted by Emperor Heinrich IV . In 1107 the Bishop of Prague pledged precious church treasures to the Regensburg Jews. Between 1150 and 1170 an important rabbinical college took place in the city.

The Talmud commentators Rabbi Isak ben Mordechai (Ribam) and Rabbi Efraim ben Isaak ("Efraim the Great") continued to work in Regensburg . The latter is considered the most important Jewish scholar of his time and made significant contributions to the further development of the teaching traditions that had been dominated by France up to that point. He gathered Talmud students from all over Germany and made a name for himself as a writer of liturgical poems, 32 of which have been preserved.

In 1196 Rabbi Jehuda ben Samuel he-Chasid ("Jehuda the Pious") founded his famous yeshiva in Regensburg , which was to make the city a center of Jewish theology for a few years . Among other things, Jehuda wrote his "Book of the Pious" there. Jehuda belonged to the Haside Ashkenaz ("the pious Germany"), a pietistic movement. The scholars Rabbi Isaak ben Jakob ha-Laban and Baruch ben Isaak also lived in the city .

In 1180 Rabbi Petachjah ben Jakob ha-Laban traveled from Regensburg via Poland , the Ukraine ( Kievan Rus ) and the Middle East to the Holy Land . After his return via Greece ( Byzantine Empire ) and Bohemia , he published the travelogue Sibbub ("round trip"). Contrary to Jewish law, Abraham ben Mose gave a widow permission to remarry in 1215 , although the body of her husband, who was missing at sea, had not been found.

The synagogue building

At the beginning of the 13th century, the community acquired several properties from the monasteries of Emmeram and Obermünster .

The synagogue was completed in 1227, after Cologne, Trier, Speyer and Worms only the fifth in the empire . The builders came from the cathedral construction works in Reims and made architectural history insofar as they introduced both the Gothic style and the two-aisled hall church for the first time in the entire Danube region . In the years that followed, Christian architecture was to be based to a large extent on the new formal language that was encountered here for the first time. Influences can be demonstrated , for example, on the south portal of St. Ulrich or in the cloister of Emmeram Monastery. The Dominican Church and the cathedral were the first Regensburg churches to be built entirely in Gothic style a few decades after the synagogue. The synagogue offered over 300 seats.

In addition, at that time the community had a Talmudic college, a school, a rabbinical court , a community hall, a hospital, a ritual bath and a new cemetery near the Gallows Hill.

Economical meaning

There is evidence of trade between Jewish merchants from Regensburg and Russia and Hungary as early as 1050 . Later, due to multiple occupational restrictions, the Regensburg Jews increasingly withdrew to banking and - since the Regensburg Jewish privilege issued by Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa in 1182 - to trading in precious metals. The Regensburg Jews were active to a considerable extent as financiers u. a. for monasteries, aristocrats, merchants, the city treasury and even the Hanseatic League. In 1297 the Salzburg bishop bought the county of Gastein with money borrowed from Regensburg Jews .

The right to live in the then Reich or the city was tied to multiple tax payments. So u had to a. an "imperial Jewish tax " to the emperor , various taxes to the bishop of Regensburg , the Bavarian duke and the city are paid. In the course of the 15th century, the Jewish community became so impoverished that it could no longer pay its taxes. After the so-called ritual murder trial from 1476 to 1480, the community was economically ruined.

Growing oppression

Nevertheless, especially as a result of the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, there was increasing persecution and oppression of the Regensburg Jews. Their right of residence was limited to the walled ghetto around Neupfarrplatz with 40 residential units. A special Jewish costume was also introduced , and in 1233 contacts between Christians and Jews and religious discussions were forbidden; Jews were no longer allowed to show themselves in public during Holy Week . Berthold von Regensburg accused the Jews of usury ; The “ Judensau ”, a medieval sculpture on Regensburg Cathedral , also bears witness to the growing anti-Judaism .

The congregation in the free imperial city of Regensburg was largely spared from the pogroms that shook large parts of Bavaria in the 14th century , not least because of the solidarity shown there by Christian fellow citizens. In the period that followed, surviving Jews from Augsburg , Nuremberg and Austria also sought protection in Regensburg.

In the second half of the 15th century, however, there was also a change in mood in Regensburg, to which penitential and conversion preachers such as Johannes von Capistrano and Peter Schwartz ("Petrus Nigri") also contributed. In 1474 the latter preached seven times three hours in the presence of the bishop to Jews who had been summoned to court - although without being able to convince them to convert. In particular, the traditional accusations of poisoning and the ritual murder of Christian children were raised again. As early as 1474, the nationally known Talmudist Rabbi Israel Bruna was charged with an alleged ritual murder, and he was only released from the resulting imprisonment after an intervention by the emperor. In 1470 the cantor Kalman was sentenced to death for allegedly abusing Christ and Mariae , in 1474 the Jew Mosse was sent to the stake .

In March 1476 six prominent members of the Jewish community were charged by the city of Regensburg with ritually murdering six Christian children. The Jewish quarter was cordoned off and the property was inventoried. A short time later, eleven other Jews with the same accusations were taken into what is known as “protective custody”. The so-called ritual murder trial was closely related to the Trento ritual murder trial (1475–1478), which in turn was based on the above. Accusations against Rabbi Israel Bruna (1474) related. The seventeen were only released in 1480 after violent intervention by Emperor Friedrich III. and the Bavarian Rabbinical Synod in Nuremberg. Although no verdict was pronounced, city prosecutors forced the released and their descendants to pledge not to take revenge for the economic ruin they had suffered. According to the specialist historian Peter Herde, “there can be no doubt” about the innocence of the accused. The emperor imposed a fine of 8,000 guilders on the city for the offense against the Jews who were under his protection. However, in 1479 he admitted to the city of Regensburg that the Jews should pay the penalty themselves. Neither the Jewish community nor the city of Regensburg could raise the money, so these financial questions remained open for a long time and only after the expulsion of the Jews in 1519 at the Reichstag in Worms in 1521 in the negotiations to settle all old debts with the imperial governor Thomas Fuchs von Wallburg have been clarified.

The religiously motivated hostility towards Jews experienced a further boost in Regensburg when in 1516 the avowed anti-Semite Balthasar Hubmaier was appointed cathedral preacher and the ritual murder accusations were raised again.

Expulsion 1519

After two unsuccessful applications to the emperor to allow the deportation of the Jews, the city council of Regensburg took advantage of the power vacuum created after the death of Emperor Maximilians I on January 12, 1519 and let the Jewish community pass the resolution on February 21 Evacuation of the synagogue and delivery for the expulsion of the Jews. The bearer of the resolution, which had already been passed on February 6, was the imperial governor Thomas Fuchs von Wallburg, who was not present when the resolution was passed, but had promoted the city's intentions. So his role in driving out the Jews was seedy. This is also supported by the fact that his name is engraved on the floor of the pilgrimage chapel that was newly built in place of the synagogue. The Jews had to leave the city within two weeks. Two “child prayer women” lost their lives in the eviction. Some of the deportees found refuge in what is now Stadtamhof and Sallern , from where they were sold in 1555 and 1577 respectively. A large part went to Poland and Tyrol .

The artist Albrecht Altdorfer was among the delegation of councilors who ordered the deportation of the Jews on the same day . Altdorfer's etchings shown above were made shortly before the expulsion, he also produced paintings, pilgrimage badges and probably sold souvenir graphics for sale while the synagogue was demolished. The Jewish quarter, including the synagogue and school, was destroyed, pledges confiscated, and valuable parchment manuscripts misused as binding material for files and books. The cemetery was desecrated, the more than four thousand gravestones were stolen, mostly used as building material, but in some cases also built into house walls by Regensburg citizens with the approval of the council as a visible macabre trophy of the “victory” over the Jews. Today about 60 of these " Jew stones " are still preserved. The street name “Am Judenstein” has been used in Regensburg since the beginning of the 17th century. It goes back to an oversized tombstone set in the earth, which was removed around 1928 when the nearby church was built. The well-known gravestone shown next door, which is currently attached to the outer wall of the “ Realschule am Judenstein ”, is a smaller one, the inscription of which was smeared with mortar or defaced with pseudo-Hebrew characters.

Just a few weeks after the expulsion, the pilgrimage to the beautiful Maria took place on the square of the former Jewish quarter , in whose creation and propagation the cathedral preacher Balthasar Hubmaier played a major role. A legal dispute arose between Bishop Johann and the city council about the income from the pilgrimage . As reasons for the illegal expulsion, the historian Peter Herde cites, in addition to the “hatred of Jews that the clergy intensified through religious and economic arguments”, the fact that “the taxpower of the Jews had greatly diminished as a result of their impoverishment,” and probably also the hope to improve the catastrophic financial situation of the city with the help of their mobile and immobile belongings. "

Modern times

Revival of the Jewish community

A small amount of Jewish life in Regensburg can only be proven again from 1669. At that time Rabbi Isaak Alexander was working there - the first Jew to publish philosophical works in German. For 140 years a house in the street Hinter der Grieb served the community as a meeting place and place of prayer .

In 1813 the Kingdom of Bavaria granted Jews citizenship ( Bavarian Edict of Jews from 1813 ); Nevertheless, numerous settlement and marriage restrictions remained. In 1822 the cemetery, which still exists today , was laid out on Schillerstraße, at the western end of the city park . In 1832 a Jewish elementary school was built , and in 1841 a prayer room was inaugurated in Untere Bachgasse. In the ten years before the founding of the Reich , the number of members of the Jewish community in Regensburg tripled from 150 to 430; the city rabbinate was elevated to the district rabbinate .

After the prayer room in Untere Bachgasse was closed in 1907 due to the risk of collapse, a synagogue in neo-Romanesque style was built on Schäffnerstrasse (today: Brixener Hof) . The building, inaugurated in 1912, offered space for 290 men and 180 women. Attached was a community center with a prayer room, a Jewish adult education center, a meeting room, a ritual bath, and apartments for the cantor , religious servant and caretaker. Last but not least, the numerous Jewish associations, which in addition to the Association for Jewish History and Literature and the Talmud Circle, also included a women's and youth association, a local branch of the Makkabi sports club , several welfare organizations and a section of the Reichsbund of Jewish Front Soldiers, gave testimony to community life . In the First World War were eleven Jewish Regensburg. In 1926 the Jewish cemetery was expanded. Tensions arose within the community between the representatives of a liberal and a more orthodox Judaism , both of which were about equally strong.

The history of the Jews in Bavaria, especially in Regensburg, was researched from 1927 onwards by the historian Raphael Straus (1887–1947), who emigrated in 1933, on behalf of the Association of Bavarian Israelitic Congregations. He wrote the works Die Judengemeinde Regensburg in the late Middle Ages (Heidelberg 1932) and Regensburg and Augsburg (Philadelphia 1939, English). Straus' documents and files on the history of the Jews in Regensburg 1453–1738 were not published again posthumously until 1960, after the entire first edition had fallen victim to the book burning .

time of the nationalsocialism

In the course of the rise of National Socialism , the new Jewish cemetery was first desecrated in 1924 and 1927. After the takeover of power , 107 Regensburg Jews were imprisoned. National Socialist thugs destroyed Jewish shops and threatened their customers - in a particularly spectacular way on March 29, 1933, when SA people with a machine gun positioned themselves in front of the entrance to the Merkur department store, which is owned by Jews. In 1934 Jews were no longer allowed to trade in the municipal market, in 1936 they were no longer allowed to trade in the municipal slaughterhouse. A total of 233 people successfully emigrated.

In the course of the November pogroms in 1938 , the synagogue on Schäffnerstrasse was burned down and destroyed as part of a planned operation. Well over 100 students from the National Socialist Motor Vehicle Training Center (NSKK) were involved in the destruction . At about 1:20 a.m. on November 10, the dome collapsed; around 2:30 a.m. the synagogue was burned out. The summoned fire brigade received strict instructions from Lord Mayor Otto Schottenheim, who was personally present , to only protect the surrounding buildings. Schottenheim prevented possible extinguishing work on the synagogue. The SS and SA devastated Jewish shops and detained the Jewish population at the police stations on Minoritenweg and Jakobstor or harassed them in various ways on the grounds of the NSKK's motorsport school on the Irler Höhe. Around 11:00 am, the Nazis drove Jews from Regensburg in a "shameful march" through Maximilianstrasse , where passers-by hit, spat at or pelted with stones. After the train ended at 12:00 p.m., a bus took around 21 Jewish men to the Dachau concentration camp , where they were held for up to six weeks. On November 10th, the Lord Mayor of Regensburg ordered the demolition of the burned-out synagogue. The costs were billed to the Jewish community. The Regensburger Anzeiger celebrated the demolition of the synagogue as the removal of a “disgrace in the heart of the city”. The Regensburg Jews were systematically expropriated . On November 25, 1940, the property of the synagogue was acquired by the City of Regensburg for 29,840 RM under the leadership of the Second Mayor, Hans Herrmann , and was soon sold on to the Volksbank Regensburg at a profit. In October 1938, the building at Unteren Bachgasse 5, which was used as a synagogue from 1841 to 1907, was demolished by order of the state - despite protests from the owner and the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments. The last Jewish shops and houses were " Aryanized ".

From 1940 the Jewish population was obliged to wear the yellow star. She was only allowed to shop in two shops, and even this only between 1:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. Other harassment included banning radios and buying pets.

On April 2, 1942, 106 Regensburg Jews were deported from the site of the destroyed synagogue to the Piaski transit camp near Lublin , and ultimately all of them were murdered in the Belzec and Sobibor extermination camps . On July 15, another family was deported to Auschwitz . After the retirement home on Weißenburger Strasse was cleared on September 23, 1942, another 39 Jewish citizens were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto . On February 15, 1945, the last ten Regensburg Jews who lived in “ mixed marriage ” with Christian partners were deported to Theresienstadt. You alone stayed alive. In total, around 250 of the Jews deported from Regensburg were murdered during the National Socialist era.

post war period

After the liberation of the concentration camps by the Allied associations in early 1945, numerous survivors arrived in Regensburg. Due to the minor damage caused by the war, there was a comparatively large amount of usable living space in Regensburg and also other accommodation options, such as B. the barracks of Messerschmitt GmbH , where 2,200 Italian concentration camp refugees were housed. The city was therefore particularly suitable for the at least temporary accommodation of Jewish refugees. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), and later the American Joint Distribution Committee, took care of their supplies . In October 1945 the establishment of the Jewish Community followed with a Jewish Chaplain's Office in Regensburg .

On May 30, 1945, Josef Glatzer was installed as rabbi ; he held this office until his emigration to the United States at the end of 1949. In the post-war period, several thousand Jews lived in Regensburg, but a large number of them emigrated to Palestine very soon as part of the migration programs of Zionist organizations and the Jewish Agency . The USA also took in hundreds of thousands of so-called displaced persons .

On August 1, 1950, the Regensburg Jewish Community was established, the successor organization to the Jewish Community . In that year the community had 288 members (June 1, 1950), in 1951 a good 200 people. Together with the 12 other Bavarian communities that were resurrected after the war, she founded the State Association of Jewish Religious Communities in Bavaria . The first rabbi was Yakob Simcha Avidor, Rabbi Kraus followed in 1956, and finally Nathan David Liebermann from 1958–1969.

In the course of negotiations between the Jewish associations and the Bavarian state, which began in 1959, regarding the return of the Jewish property expropriated by the Nazis and the corresponding compensation payments, the Jewish community believed that it failed to adequately and adequately explain its claims.

present

Despite the relatively small number of members, the unfavorable demographic structure and the resulting problematic financial situation, Jewish community life soon developed again in Regensburg. Traditionally, great value was placed on education and training. As early as 1951 and 1953, a Jewish kindergarten and a Hebrew school were established again. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain and the associated immigration from the states of Eastern Europe, the number of members of the Regensburg Jewish Community has increased again to almost 1000 members. In addition, there are 200 to 300 people who have not yet received recognition as Jews, particularly because of missing papers. Another 200 people belong to the community, mostly non-Jewish family members. Until his death in 2007 Otto Schwerdt was the long-time chairman of the Israelite Community of Regensburg.

Relations with the non-Jewish environment developed positively after the war, with the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation playing a central role, but also the good contacts between the Jewish community and the city of Regensburg, the government of the Upper Palatinate and the district assembly. The dialogue also received considerable impetus from the construction of the new multi-purpose parish hall in 1969, which has become a place of encounter between religions: In addition to meetings with the most diverse population groups, with parties, churches and parishes, numerous guided tours, short seminars and lectures take place there.

The local political disputes over the excavation of the ghetto at Neupfarrplatz (1995–1997) aroused strong civic engagement, which had an impact on the extent and type of excavations. In 2005, the Israeli artist Dani Karavan erected the Misrach monument, a floor relief made of white granite blocks, on the exact site of the medieval synagogue that was destroyed in 1519, which reproduces the floor plan and the foundations of the building. A documentation center was set up in the immediate vicinity. On September 13, 2006, on the mediation of Bishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, the Jewish Community of Regensburg hosted during Pope Benedict XVI's visit to Bavaria . part of their entourage with kosher food.

Since 2016, the Jewish Community Center and Synagogue of Regensburg have been built on the site of the synagogue that was destroyed in 1938 . The building planned by Staab Architekten was inaugurated on February 27, 2019.

literature

- Karl Bauer : Regensburg. 4th edition. Regensburg 1988, ISBN 3-921114-00-4 , especially pp. 126-129.

- Barbara Beuys : Home and Hell - Jewish life in Europe through two millennia. Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-498-00590-1 .

- Herbert E. Brekle : The Regensburg Ghetto. Photo impressions from the excavations. MZ Buchverlag, Regensburg 1997, ISBN 3-931904-17-2 .

- Christoph Daxelmüller : The rediscovered world of the Regensburg Jews of the Middle Ages. In Regensburger Almanach 1996. Regensburg 1996, pp. 146–155.

- Arno Herzig : Jewish History in Germany. Munich 1997, ISBN 3-406-47637-6 .

- Barbara Eberhardt, Cornelia Berger-Dittscheid (arrangement): Regensburg. In: Wolfgang Kraus , Berndt Hamm, Meier Schwarz (eds.): More than stones ... Synagogue memorial volume Bavaria. Volume I. Kunstverlag Josef Fink, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, ISBN 978-3-89870-411-3 , pp. 261–285.

- Sylvia Seifert: Insights into the life of Jewish women in Regensburg. Part 1 and 2. In: Ute Kätzel, Karin Schrott (eds.): Regensburger Frauenspuren, a historical journey of discovery. Regensburg 1995, ISBN 3-7917-1483-X , pp. 86-106 and pp. 151-161.

- Roman Smolorz : Displaced Persons. Authorities and leaders in the budding Cold War in eastern Bavaria. 2nd Edition. Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935052-53-5 , especially pp. 128-139.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Herde: Regensburg (local article). In: Arye Maimon, Mordechai Breuer (ed.): Germania Judaica Volume III, 2nd Part, Tübingen 1995, pp. 1178-1229, here 1186 and 1202.

- ↑ Peter Herde: Regensburg (local article). 1995, p. 1193.

- ^ Robert Werner: The Regensburg ritual murder accusations - Sex pueri Ratisbonae. Developments, connections with Trient and Rinn, relics. In: Historischer Verein Regensburg, Oberpfalz (ed.): Negotiations of the Historischer Verein für Oberpfalz and Regensburg 150 (VHV0) 2010, pp. 33–117, here p. 41.

- ^ Peter Herde: Formation and crisis of the Christian-Jewish relationship in Regensburg at the end of the Middle Ages. In: Journal for Bavarian State History. (ZBLG) 22, 1959, pp. 359–395, here 382. In view of the historical fact that not a single Christian child was missing in this context, Herde speaks of a “ritual murder psychosis”.

- ↑ Peter Brielmeier, Uwe Moosburger, Regensburg Metropole im Mittelalter, Verlag Pustet, 2007, p. 244/245, ISBN 978-3-7917-2055-5

- ↑ Tobias Beck, Emperor and Imperial City at the Beginning of the Early Modern Age. The Reich Main Team in the Regensburg Regimental Orders 1492–1555 , Regensburger Studien 18, 2011, pp. 116–117, ISBN 978-3-935052-89-4 ( table of contents )

- ^ Carl Theodor Gemeiner: Regensburgische Chronik Volume IV, 1824, ND 1987, p. 356.

- ↑ Achim Hubel: The beautiful Maria of Regensburg. In: Helmut-Eberhard Paulus (Hrsg.): Regensburger Herbstsymposion Vol. 3, Regensburg 1997, p. 93. One of the etchings bears the significant heading: "In 1519 the Jewish synagogue in Regensburg was completely destroyed according to God's righteous advice" .

- ^ Robert Werner: The Regensburg ritual murder accusations. 2010, p. 109.

- ↑ Peter Herde: Regensburg. (Ortschaftsartikel), In: Arye Maimon, Mordechai Breuer u. a. (Ed.): Germania Judaica. (GJ) Volume III, 2nd part, Tübingen 1995, pp. 1178-1229, here 1202.

- ^ Regensburg. In: More than stones ... Synagogue Memorial Band Bavaria. Volume 1, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, p. 274.

- ↑ a b c d e Regensburg. In: More than stones ... Synagogue Memorial Band Bavaria. Volume 1, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, p. 275.

- ↑ Helmut Halter: City under the swastika. Local politics in Regensburg during the Nazi era. (edited by the museums and the archives of the city of Regensburg), 1994, pp. 77–87, here 189. In the so-called “synagogue fire trial” in 1949, Schottenheim was acquitted, although he was at the scene of the crime before the fire brigade arrived .

- ↑ Reichspogromnacht in Regensburg: Spitting, looting and forgetting ... on Regensburg-digital.de

- ↑ Helmut Halter: City under the swastika. 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Regensburg. In: More than stones ... Synagogue Memorial Band Bavaria. Volume 1, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Andreas Angerstorfer : Until the Holocaust , article on the homepage of the Jewish community. ( Memento of the original from August 16, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Eugen Trapp: Regensburg in the summer of 1945, literary mood pictures by the Milanese painter Aldo Carpi . In: Negotiations of the historical association for Upper Palatinate and Regensburg . tape 154 . Historical Association for Upper Palatinate and Regensburg, 2014, ISSN 0342-2518 , p. 261-274 .

- ^ Regensburg. In: More than stones ... Synagogue Memorial Band Bavaria. Volume 1, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, p. 281.

- ^ Regensburg. In: More than stones ... Synagogue Memorial Band Bavaria. Volume 1, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, p. 278.

- ^ Regensburg. In: More than stones ... Synagogue Memorial Band Bavaria. Volume 1, Lindenberg im Allgäu 2007, p. 280.

- ^ Herbert E. Brekle: The Regensburg Ghetto. 1997, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ synagoge-regensburg.de

- ^ House of the New Beginning, accessed on March 5, 2019

- ^ Mittelbayerische.de: Regensburgs Synagoge: Certainly very open

Web links

- Jewish community of Regensburg

- Jewish community of Regensburg on Alemannia-Judaica (including many photos)

- Jewish Life in Regensburg - Synagogue, Ghetto, Scholars ( Memento from February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (MP3; 20.9 MB) Podcast for the radioWissen broadcast on January 20, 2014.

- Everything Kosher !? Jewish life in Regensburg. (Documentation of a project of the Realschule am Judenstein )