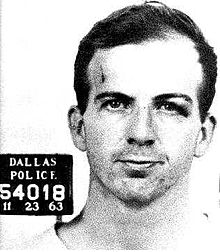

Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (born October 18, 1939 in New Orleans , Louisiana , † November 24, 1963 in Dallas , Texas ) was the alleged murderer of the American President John F. Kennedy . Two days after the attack , Oswald was shot dead by nightclub owner Jack Ruby while in police custody .

Life

youth

Oswald was one of two sons of Robert Edward Lee Oswald (1896-1939) and his wife Marguerite Frances Claverie (1907-1981). His father died three months before he was born. Oswald had a biological brother, Robert EL Oswald Jr., and a half-brother named John Pic from his mother's previous marriage. At the end of 1942 the mother placed the three boys in an orphanage , from which she brought them back to herself in early 1944. In 1945 she married the businessman Edwin Ekdahl, the marriage was divorced in 1948. The family moved frequently in Oswald's youth - around twenty addresses of his are known, including in Fort Worth , New Orleans and the Bronx in New York City . Oswald was a rather introverted child who often skipped school . In 1953, a New York court ordered a three-week psychiatric examination in a juvenile detention center, which showed a personality disorder with schizoid aspects and passive-aggressive tendencies. In particular, the relationship with his mother, a dominant and emotionally unstable woman, is described as problematic. The mother withdrew him from the subsequent placement in an institution for emotionally disturbed young people by moving again. During this time he developed a keen interest in Marxism . He entered into a lively correspondence with the Socialist Workers Party , but did not join it.

Military career

At the age of 16, he briefly joined a militia called Civil Air Patrol (CAP) in New Orleans. The unit also temporarily included the pilot and later private detective David Ferrie , who had been involved in secret operations against Cuba covered by the CIA during those years . On October 26, 1956, at the age of 17, Oswald began training with the United States Marine Corps . There he proved to be a slightly below-average shooter: When checked with the M1 rifle , he just achieved the required shooting performance for qualified shooters in the three-stage American system, which corresponded to a medium classification ("sharpshooter"). He later worked in air surveillance and trained on radar at the Naval Air Technical Training Center in Jacksonville , Florida . Oswald stood out because he confessed to being a Marxist-Leninist . During this time he learned Russian and had a subscription to Pravda .

On August 22, 1957, after completing his training, he was stationed at the secret air force base Atsugi in Japan , from where the Lockheed U-2 - at that time one of the most secret projects of the United States Air Force - started on spy flights towards the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China . It was there that Oswald came into contact with top secret information for the first time. To avoid being transferred to the Philippines , where he was to continue his training, Oswald deliberately shot himself in the arm with his pistol in October 1957. A military court sentenced him to twenty days of hard labor for illegally possessing weapons, and was subsequently transferred. A second military sentence , this time 28 days of detention, followed in June 1958 after he had poured a drink on a sergeant's head. In November 1958 Oswald was stationed at the El Toro naval base in California , but asked for early release in August 1959 because of the poor health of his mother, which he was granted on September 11, 1959, four weeks before his regular service expired.

In the Soviet Union

Oswald's original plan was to move to Cuba , where Fidel Castro's July 26th Movement had just taken power. Instead, he went to Europe by ship from New Orleans and entered the Soviet Union via Helsinki . On October 16, 1959, he reached Moscow . In a letter dated October 17, Oswald wrote to the Soviet authorities that he wanted to become a Soviet citizen . The authorities then informed him that his tourist visa had expired. A suicide attempt (he cut his wrists) saved him time. On October 31, he went to the American embassy in Moscow to give up his American citizenship. However, he was turned away because the department responsible was vacant that day.

The Soviet authorities did not know at the time whether they could trust Oswald or whether he was an American agent. With the appearance in the American embassy he obviously wanted to underline his trustworthiness. The KGB recommended that he be granted a one-year residence permit and put him through its paces. In the first year he was around the clock by agents intercepted the Soviet secret service, and every word was recorded. He lived largely isolated in a Moscow hotel.

On January 8, 1960, Oswald arrived in Minsk . On January 13th, he started a job as a metal worker in a factory that manufactured radio and television sets, among other things. He received 700 rubles a week, had affairs and enjoyed the courtesies given to a defector. His temporary residency permit was easily renewed, although the change from his honorable release from the Marines to a dishonorable one in September seemed to suit him. He later met the pharmacology student Marina Nikolajewna Prussakowa (born July 17, 1941 in Molotovsk, today Severodvinsk , Russia), the niece of a colonel in the Soviet secret service, who initially thought he was Baltic because of his accent . They married on April 30, 1961. Their first child, June Lee Oswald, was born on February 15, 1962.

Return to the United States

Oswald was soon dissatisfied in the Soviet Union: The Soviets had "perverted" the teachings of Karl Marx , so his impression. On February 13, 1961, he asked the American embassy for help with his return, and his wife applied for a visa for the United States. Over a year later, on May 10, 1962, he was informed that his return to the United States had been arranged. The Soviet authorities did not put any obstacles in their way either. On June 13, 1962, Oswald returned to the United States with his family. The State Department advanced the travel expenses and issued him a passport.

Immediately after the Oswalds arrived in New York City, the family moved to Fort Worth, Texas. There Oswald sought contacts with exiled Russians because his wife could not yet speak English and was homesick. In this way he met George de Mohrenschildt (1911-1977), a wealthy Russian nobleman with intelligence contacts. Mohrenschildt also introduced him to Michael (* 1928) and Ruth Paine (* 1932), who lived in Irving (Texas) , a suburb of Dallas. The separated couple were politically left-wing and wanted to learn Russian. Ruth Paine in particular began to take care of the Oswalds, whose marriage was in crisis. On October 8, 1962, the Oswalds moved to Dallas. There Oswald initially worked in a welding shop , but quit after three weeks and took a job at Jaggars-Stovall-Chiles , which produced, among other things, military maps for the United States Army, the United States Department of Defense and other authorities. Oswald had no access to the areas with the documents classified as secret. However, he used the company's available equipment to produce false identification papers in the name of Alek James Hidell. After his superiors had already had reason to complain about Oswald's poor work performance and his rude behavior - there had almost been fights in the company on several occasions - they fired him on April 1, 1963 because he was reading the Soviet satirical magazine Krokodil in the canteen would have.

One day before his resignation, Oswald had himself photographed in the back yard of his Dallas home. In the pictures he posed with a rifle , a pistol and the communist newspapers The Militant and The Worker . To prove his revolutionary sentiments, he sent it to The Militant , where one was amazed at the naivety of the sender, who presented a Trotskyist and a Stalinist paper at the same time. Marina Oswald later repeatedly stated that she had taken the pictures; the Warren Commission accepted them as Exhibits 133-A and CE 133-B. The House Select Committee on Assassinations also came to the conclusion in 1979 that they were authentic. After his arrest, Oswald described the photos as fakes. New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison thought the picture was a photomontage because the shadow of Oswald's body was pointing in a different direction than that of his nose. This line of reasoning was followed by various theories that question the single perpetrator theory. According to research by Hany Farid, a professor of computer science at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire , the shadow fall is natural, so the images are not manipulated.

Ten days later, on April 10, 1963, Oswald tried to shoot the out-of-service right-wing radical Major General Edwin A. Walker . He had been removed from his command by President Kennedy in 1961 because he had distributed propaganda pamphlets from the John Birch Society among his subordinates. As a result, Walker left the military and returned to Texas. For this attack, Oswald used the rifle that can be seen in the photo taken on March 31, which he had sent to a post office box that same month under his false name A. Hidell. He also bought a revolver by post at this time. Oswald had observed Walker's house several days beforehand and had also taken photos. In case he was arrested after the attack, he left a note in Russian for his wife. Walker was working on his tax return in the dining room of his house when he was shot at from about thirty yards on April 10, 1963. The bullet was deflected by the wooden window frame and only injured the ex-general on the forearm. The Dallas police did not suspect Oswald after the failed murder attempt. It was only after the assassination attempt on the president that the aforementioned note and photos of Walker's house were found in his apartment. Thereupon his widow also stated that Oswald had planned to shoot the general, but had only told her about it after the attack.

In April 1963 Oswald went to New Orleans, where he initially lived with his uncle Charles Murret, a bookmaker and petty criminal with ties to the American mafia . Murret lent him money until Oswald found a job with the Reily Coffee Company. In May 1963 his family also moved to New Orleans.

The summer before the attack

In the summer of 1963 Oswald tried to infiltrate the anti-communist Cuban exile scene in New Orleans. So he offered Carlos José Bringuier , as an ex-marine, he could train Cuban exiles and help in the fall of Castro. At the same time he was committed to the organization Fair Play for Cuba Committee , of which he was the only member in New Orleans. He protested against a possible American invasion of Cuba on leaflets that he distributed. The address was stamped on New Orleans at 544 Camp Street . FBI agent Guy Banister lived in the same building, albeit at a different address. How Oswald financed the printing of the leaflet is unknown. His attorney Dean Andrews later reported to the Warren Commission that Oswald had been paid to distribute it; there is also a testimony according to which Oswald was given an envelope. When Oswald was distributing copies of this leaflet on Canal Street, he was confronted and beaten up by Bringuier and two other Cubans in exile. The police arrested the four. Oswald was charged with disturbing public order by a fine 10 US dollars occupied. His uncle Murret contacted the Mafioso Emile Bruneau, who released Oswald by depositing bail.

These events caught the attention of local reporter William Stuckey, who reported about it on his radio show Latin Listening Post on WDSU . The radio station gave Oswald two appointments to present his position, which he took on August 17 and 21 and in which he posed as a supporter of Fidel Castro and a Marxist-Leninist .

On September 24, 1963, Oswald left New Orleans. His wife and daughter June had already been taken to Dallas by car from Ruth Paine on September 23. Oswald himself traveled by bus to Mexico City, where he tried in vain to get a visa for Cuba. He returned to New Orleans on October 4, 1963. Nine days later, through the mediation of Ruth Paine, he got a job at the Texas School Book Depository . His second daughter, Audrey Marina Rachel Oswald, was born on October 20th. The couple were already separated at the time: Marina lived with the children in Irving, her husband under a false name in Dallas. One reason for the overall unhappy outcome of the marriage was Oswald's continued violence against his wife.

The assassination

→ Main article: Assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy

On the morning of November 22, 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald began work at 8:00 a.m. at the Texas School Book Depository . From there he is said to have fired the fatal shots at US President John F. Kennedy at around 12:30 p.m. Afterwards Oswald is said to have left his work and went to his room, which he rented under the name OH Lee .

Around 40 to 45 minutes after the assassination attempt on Kennedy, Oswald shot and killed JD Tippit , a police officer who was on patrol in the Oak Cliff residential area. The scene of the crime was about a mile from Oswald's apartment, where, according to his landlady, he arrived at around 1 p.m., only to leave it a few minutes later. It is believed that because of the now widespread description of the suspect in the Kennedy murder, Tippit stopped Oswald, whereupon Oswald lost his nerve, shot the police officer and fled on foot. When Oswald was arrested by around 15 police officers in the nearby Texas Theater at around 1:50 p.m. , he was carrying a revolver that could be used as a weapon based on the bullets seized in Tippit's body and the cartridge cases at the scene.

After his arrest, Oswald was interrogated for twelve hours. His testimony was not recorded, as the standard Dallas police procedure at the time did not provide for during interrogation. Paraffin casts were taken from his hands and cheek , which were chemically examined for traces of nitrate . This was to check whether he had fired any firearms in the past few hours. The test results on his hands were positive, the one on his cheek negative, which Vincent Bugliosi attributes to differences in the design of the two types of weapon: While there is a gap between the chamber and barrel in a revolver from which gun smoke can escape, this is the case with one Rifle not the case.

Oswald denied the policeman's murder. And when asked whether he had shot President Kennedy, he replied: “I did not shoot anyone!” And “I was arrested for living in the Soviet Union!” When Oswald found out at the first public performance the following day, that he should be charged with the murder of Kennedy, he exclaimed, “I'm just a scapegoat ! (I'm just a patsy!) ".

Up to a third of all hearing witnesses of the Kennedy murder stated that the shots did not come from the school book warehouse, but from a grassy hill on Dealey Plaza . Just under 9% heard four or more shots. In academic historical research on Kennedy's life and politics, the prevailing view is that Oswald shot the president as a lone perpetrator.

assassination

On November 24, 1963, two days after his arrest, Oswald was shot in the stomach by nightclub owner Jack Ruby while he was being transferred to Dallas State Prison at 11:21 a.m. Oswald died at 1:07 p.m. in the city's Parkland Hospital.

Ruby had been able to enter the police building unhindered, the murder took place in front of the cameras. The fact that key witnesses were not admitted to the preliminary investigation by the Warren Commission and that evidence was withheld contributed significantly to the controversies and conspiracy theories in the murder case that have continued to this day, as has the role of the victim - a symbol of a renewing America . In 1981, Oswald's body was exhumed to investigate the suspicion that had arisen in the course of these theories that someone else had been buried in his place and that Oswald's body was in a secret location. The suspicion could not be confirmed.

Oswald was buried on November 25, 1963 (the same day as John F. Kennedy) in Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park in Fort Worth , Texas.

Reception in the novel

The American writers Don DeLillo and Norman Mailer processed the life story of Oswald in their books Seven Seconds (1988) and Oswald's Tale: An American Mystery (1995), respectively . The work The attack by the writer Stephen King is an extensively researched time travel novel based on the events of the Kennedy assassination.

literature

- Scott P. Johnson: The Faces of Lee Harvey Oswald: The Evolution of an Alleged Assassin. Lexington Books, Lanham 2013, ISBN 978-0-7391-8682-4 .

- Dorian Hayes: Oswald, Lee Harvey. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 564-569.

- Gerald Posner : Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK . Random House, New York 1993, ISBN 978-0-679-41825-2 .

Movie and TV

- Ruby and Oswald - Mel Stuart's 1978 televised film is largely based on the findings of the Warren Commission.

- In the film JFK - Tatort Dallas (1991) by Oliver Stone , Oswald is played by Gary Oldman .

- In the 2006 documentary Rendezvous with Death: Why John F. Kennedy Had to Die , Wilfried Huismann argues that Lee Harvey Oswald acted on behalf of the Cuban secret service.

- Parkland - Feature film (2013) by Peter Landesman , in which it remains open whether Oswald is Kennedy's killer.

- 11.22.63 - The attack (2016), a television series in which a time traveler tries to prevent the assassination attempt on Kennedy. Oswald is played by Daniel Webber .

Pop Culture

Oswald is mentioned by name in the Manic Street Preachers song I'm just a patsy . A sample of the “Patsy” claim is also used.

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerald Posner : Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Random House, New York 1993, pp. 5-19.

- ^ A b Dorian Hayes: Oswald, Lee Harvey. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / London 2003, Volume 2, p. 564.

- ^ Gerald Posner: Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Random House, New York 1993, pp. 142 f.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato : The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Dorian Hayes: Oswald, Lee Harvey. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / London 2003, Volume 2, p. 565.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 161 f.

- ^ David Kaiser : The Road to Dallas. The Assassination of John. F. Kennedy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2008, p. 33 f.

- ^ Gerald Posner: Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Random House, New York 1993, p. 56.

- ^ Gerald Posner: Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Random House, New York 1993, p. 64.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, pp. 166-169.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 168 f.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Volume XIX , p. 288 at The Assassination Archives and Research Center

- ^ John McAdams: JFK Assassination Logic. How to Think About Claims of Conspiracy. Potomac Books, Dulles, VA 2011, p. 162.

- ↑ Dartmouth Professor finds that iconic Oswald photo was not faked ( Memento of the original from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Dartmouth College press release November 5, 2009

- ↑ Christopher Schrader: The human stain. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung of November 13, 2009.

- ^ John McAdams: JFK Assassination Logic. How to Think About Claims of Conspiracy . Potomac Books, Dulles, VA 2011, pp. 165 ff .; David Kaiser: The Road to Dallas. The Assassination of John. F. Kennedy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2008, pp. 182-186; Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 170 f.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 173.

- ^ David Kaiser: The Road to Dallas. The Assassination of John. F. Kennedy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2008, pp. 210-219; Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 173.

- ^ David Kaiser: The Road to Dallas. The Assassination of John. F. Kennedy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 2008, pp. 210-219; John McAdams: JFK Assassination Logic. How to Think About Claims of Conspiracy . Potomac Books, Dulles, VA 2011, pp. 88-96; Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, pp. 173 and 469.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 177 f.

- ↑ Vincent Bugliosi : Four Days in November. The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. WWNorton, New York 2007, pp. 1 ff.

- ^ Gerald Posner: Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Random House, New York 1993, pp. 82, 92 and 98.

- ↑ Vincent Bugliosi: Four Days in November. The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy , WWNorton, New York 2007, p. 116 f .; Larry J. Sabato: The Kennedy Half-Century. The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy . Bloomsbury, New York 2013, p. 249.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Vol. III , p. 512 (testimony by Joseph Nicol)

- ^ Gerald Posner: Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Random House, New York 1993, p. 343 (note).

- ^ Gerald Posner: Case Closed. Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK , Random House, New York 1993, p. 348 f; Vincent Bugliosi: Four Days in November. The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy . WW Norton, New York 2007, pp. 260 ff.

- ↑ Vincent Bugliosi: Four Days in November. The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy , WWNorton, New York 2007, p. 256.

- ^ John McAdams, Dealey Plaza Earwitnesses ( accessed online July 18, 2011).

- ↑ This is the assessment of the Berlin history professor Knud Krakau: "As a result, historiography and serious journalism tend to assume that Oswald was the sole perpetrator - even if only because all the alternatives are even less convincing (Norman Mailer; Gerald Posner)", Knud Krakau: John F. Kennedy. November 22, 1963. In: Alexander Demandt (Ed.): Das Attentat in der Geschichte , area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 421; Alan Posener , John F. Kennedy in personal reports and picture documents , Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek 1991, pp. 126–138; Seymour Hersh , Kennedy. The end of a legend. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1998; Robert Dallek : John F. Kennedy. An unfinished life. DVA, Munich 2003, p. 645; Jürgen Heideking : John F. Kennedy 1961–1963. The imperial president. In: The American Presidents. 42 historical portraits from George Washington to George W. Bush. ed. by Jürgen Heideking and Christof Mauch, 4th edition. CH Beck 2005, p. 359; Michael O'Brien: John F. Kennedy. A biography. Thomas Dunne Books, New York 2005, pp. 903f; Jürgen Heideking , Christof Mauch : History of the USA. 5th edition. A. Francke, Tübingen 2007, p. 326; Willi Paul Adams : The USA in the 20th Century. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, p. 99.

- ↑ Vincent Bugliosi: Four Days in November. The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy , WWNorton, New York 2007, p. 510 f.

- ^ Peter D. Knight: Conspiracy Culture. From the Kennedy Assassination to the X-Files. Routledge, London and New York 2000, p. 97.

- ↑ http://www.stephenking.com/index.html

Web links

- Lee Harvey Oswald in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Lee Harvey Oswald in the catalog of the German National Library

- Lee Harvey Oswald in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Biography of Oswald with many photographs

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Oswald, Lee Harvey |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hidell, Alek J .; Oswald, Leon; Lee, OH |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | alleged murderer of John F. Kennedy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 18, 1939 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New Orleans , Louisiana |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 24, 1963 |

| Place of death | Dallas , Texas |