Rojava

|

Autonomous Administration of Northern and Eastern Syria - Rojava Rêveberiya Xweser a Bakur û Rojhilatê Sûriyeyê (kurd.) |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

De facto regime , area is part of under international law |

Syria | ||||

| Official language | Kurmanji , Arabic and Aramaic | ||||

| Seat of government | Ain Issa | ||||

| Form of government | Democratic Confederalism | ||||

| Head of government |

de facto: Chair of the Executive Committee: Îlham Ehmed and Mansur Selum |

||||

| population | 4.6 million (2014 estimate) | ||||

| currency | Syrian pound | ||||

| founding | March 17, 2016 as the Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava | ||||

| Time zone | OEZ | ||||

| Telephone code | +963 | ||||

The Autonomous Administration of Northern and Eastern Syria - also known by the Kurdish name Rojava ( pronunciation: [roʒɑːˈvɑ] ; Kurdish رۆژاڤایا کوردستانێ, Rojavaya Kurdistanê ; Arabic كردستان السورية, DMG Kurdistān as-sūriyya , Aramaic ܦܕܪܐܠܝܘܬ݂ܐ ܕܝܡܩܪܐܛܝܬܐ ܕܓܪܒܝ ܣܘܪܝܐ Federaloyotho Demoqraṭoyto l'Gozarto b'Garbyo d'Suriya ), in German West Kurdistan , is a de facto autonomous area in Syria . On March 17, 2016, a meeting of Kurdish , Assyrian-Aramaic , Arab and Turkmen delegates proclaimed the autonomous federation of Northern Syria, which at that time consisted of the cantons of Afrin , Kobanê and Cizîrê .

Surname

In the Kurdish language Kurmanji , the term Rojava is made up of the Kurdish words roj (“sun / day”) and ava (“end / setting (of the sun)”) and literally means “sunset”. The term also means west and can be understood as the western sub-region of the historical settlement region of the Kurds.

Geography and administration

Rojava roughly corresponds to the predominantly Kurdish regions in northern Syria along the border with Turkey , which are separated from each other by areas populated by Arabs. Because of this territorial separation, older Kurdish authors did not speak of a "Syrian Kurdistan", but only of "Kurdish areas in Syria". The region is mountainous in the west around Afrin, while the rest consists of plains that are further east through various rivers such as the Euphrates and the Chabur are watered. The area around Hasakah, also known as Jazīra , consists of fertile plains. The Syrian Desert begins south of Rojava .

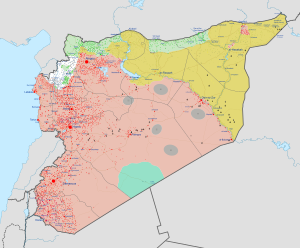

From an administrative point of view, Rojava consists of parts of the Syrian governorates of Aleppo , al-Hasakah and ar-Raqqa . After the Syrian army withdrew from the north as far as possible in 2012, three cantons (Afrin, Kobani and Cizre) were declared by the Kurdish rulers. However, in the course of the Syrian civil war, the borders of Rojava changed, so that both the name (away from Rojava towards the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria ) and the administration went through an evolution. With cities like Manbij , ath-Thaura , ar-Raqqa and al-Schaddadi , large non-Kurdish areas came under the Rojava administration. With the fall of the canton of Afrin to Turkey and its allied Syrian forces in February 2018, Rojava suffered a significant loss.

The difference between the claim of the Kurdish parties to an autonomous northern Syrian territory and the de facto state (military and political) should also be considered. As a result of a restructuring in 2017, the cantons were renamed into regions, which are then divided into further smaller units.

History of origin

The Kurdish minority in Syria was discriminated against for decades under the Arab nationalist Ba'ath regime. In the course of the civil war in Syria , the Syrian government gave up control of the regions on the northern border towards the end of 2013. Local Kurdish forces took control in many places. On November 12, 2013, the "Party of the Democratic Union" (decided Democratic Union Party , PYD), together with the Christian - Syrian Unity Party (an Assyrian / Aramaic Party) and set up a transitional administration other small parties in northern Syria, dating from around the by the war To counter deficiencies in administration and supply of the population. The administration was established in Cizîrê on January 21, 2014, in Kobanê on January 27, and a few days later in Afrin.

On March 17, 2016, a meeting of Kurdish, Assyrian, Arab and Turkmen delegates in Rumaylan proclaimed an autonomous federation of Northern Syria - Rojava , consisting of the three cantons of Rojavas. Neither the USA and Russia, nor the Assad regime and the Syrian opposition support the drive for autonomy.

The Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava has representations in Moscow , Stockholm and, since May 2016, also in Paris and Berlin . The aim of the representation is to establish diplomatic relations with the German state and to inform the public about the developments in Rojava, explained the representative of the autonomous region, Sipan Ibrahim. "We want to make it clear to the people in Germany that in Rojava Kurds, Arabs and other population groups live together like brothers and sisters." There is also a representative of the self-defense armed forces YPG in Prague .

population

The officially checked Rojavas in spring 2016 areas correspond approximately to the Syrian government units District Afrin , Ayn al-Arab district and Tall Abyad district and the Al-Hasakah Governorate . According to the 2004 census, these four administrative units had a population of around 1,900,000 people. The population consisted predominantly of Kurds, Arabs and Assyrian-Aramaeans . The civil war resulted in both emigration and immigration of refugees. In 2014 the population was estimated at around 4.6 million.

This list contains all cities in Rojava with more than 10,000 inhabitants according to the 2004 census. Cities in gray are in some areas under the control of the Syrian central government, such as the airport and the border crossing to Turkey in Qamishli. The capitals of the three cantons are in bold.

| Surname | (Kurdish) | (Arabic) | (Aramaic) | 2004 residents | Canton |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| al-Hasakah | Hesîçe | الحسكة | ܚܣܟܗ | 188.160 | Cizîrê |

| Qamishli | Qamişlo | القامشلي | ܩܡܫܠܐ | 184.231 | Cizîrê |

| Manbij | Minbic | منبج | ܡܒܘܓ | 99,497 | Afrin |

| Ain al-Arab | Kobanî | عين العرب | 44,821 | Kobane | |

| Afrin | Afrin | عفرين | ܥܦܪܝܢ | 36,562 | Afrin |

| Raʾs al-ʿAin | Serêkaniyê | رأس العين | ܪܝܫ ܥܝܢܐ | 29,347 | Cizîrê |

| Amude | Amûdê | عامودا | 26,821 | Cizîrê | |

| al-Malikiyah | Dêrika Hemko | المالكية | ܕܪܝܟ | 26,311 | Cizîrê |

| Tall Rifaat | Arpet | تل رفعت | 20,514 | Afrin | |

| al-Qahtaniyah | Tirbespî | القحطانية | ܩܒܪ̈ܐ ܚܘܪ̈ܐ | 16,946 | Cizîrê |

| Ash-Schaddadi | Şeddadê | الشدادي | 15,806 | Cizîrê | |

| al-Mu'abbada | Girkê Legê | المعبدة | 15,759 | Cizîrê | |

| Tall Abyad | Girê Spî | تل أبيض | 14,825 | Kobane | |

| as-Sab'a wa Arba'in | السبعة وأربعين | 14,177 | Cizîrê | ||

| Jindires | Cindarêsê | جنديرس | 13,661 | Afrin | |

| al-Manajir | Menacîr | المناجير | 12,156 | Cizîrê |

Political system

administration

The administration is supposed to reflect the multi-ethnic and multi-religious situation in Northern Syria and consists of one Kurdish, one Arab and one Christian-Assyrian minister per department. Overall, the plan is to build a democratic system in the sense of self-governing democratic confederalism based on the work of Abdullah Öcalan , for example a 40% quota of women in the administration is targeted. According to the PYD , the longer-term plan is to unite all three cantons under one administration. On July 27 and 28, 2017, the Constituent Council of the Federation of Northern Syria decided to reorganize the administrative regions. The federation therefore currently consists of the three federal regions Cizîrê, Firat and Afrin. The federal regions are divided into 6 cantons, namely Cizîrê in the cantons Hesekê and Qamişlo, Firat in the cantons Kobanê and Girê Spî and Afrin in the cantons Efrîn and Şehba.

With this move, however, the PYD met with criticism both within Syria and internationally. One point of criticism is that the PYD also claims predominantly non-Kurdish populated areas for the contiguous stretch of land "Rojava" in northern Syria, which v. a. meets resistance from the Arab-Sunni majority in these areas.

In the social contract of Rojava , the administration of the de facto autonomous areas pledges to respect human rights. In particular, to differentiate between the Syrian government and ISIS, the following are mentioned:

- Equal Rights for Women

- Religious freedom

- Prohibition of the death penalty

Syrian laws only apply insofar as they do not contradict the principles of the social contract.

elections

Local elections September 2017

Local elections took place on September 22, 2017, in which the co-chairs of the 3,732 local authorities were elected. One man and one woman are elected co-chairpersons for each municipality. For many it was the first time that they got to vote.

Regional council elections December 2017

Regional council elections were held on December 1, 2017. Two electoral alliances took part. The “List of the Democratic Nation” (Lîsteya Hevgirtina Neteweya Demokratîk, LND) consists of 17 parties that are related to the PYD . And the Kurdish National Alliance (Lîsteya Koalîsyona Neteweyî ya Kurd a Sûriyeyê, LKNKS) in Syria which consists of 5 parties, of which 4 parties were previously close to the Kurdish National Council (ENKS), which was boycotting the elections . The ENKS excluded the 4 parties because they work together with the PYD.

Results of the regional council elections December 2017

Cizre region:

Total number of seats on all councils that stood for election: 2902

- LND: 2718 seats

- LKNKS: 40 seats

- Independent: 144 seats

Euphrates region:

Total number of seats on all councils that stood for election: 954

- LND: 847 seats

- LKNKS: 40 seats

- Independent: 67 seats

Afrin region:

Total number of seats in all councils that stood for election: 1175 seats

- LND: 1056 seats

- LKNKS: 72 seats

- Independent: 40 seats

- Syrian Alliance list: 8 seats

economy

The economic order in Rojava is based on the principles of democratic confederalism based on the work of Abdullah Öcalan . Private property and entrepreneurship are protected according to the principle of "ownership through use". Dara Kurdaxi, an economist from Rojava, formulated the principle: "The method in Rojava is less directed against private property, but rather aims to private property to provide all citizens of Rojava in the service." The focus of the economic policy is based on an extension of public service and cooperative economic activity; several hundred cooperatives with mostly between 20 and 35 members have been founded since 2012. According to information from the Ministry of Economic Affairs, around three quarters of the land was under public management at the beginning of 2015 and one third of industrial production was provided by companies administered by workers' councils. There are no taxes in Rojava ; the administration's income comes from customs duties and the sale of extracted oil and other natural resources. Public administration employees are partially paid by the Syrian central government.

The economy in Rojava has experienced comparatively less destruction in the civil war than other parts of Syria and has coped with the circumstances comparatively well. In May 2016, Ahmed Yousef, Minister of Economics and President of Afrin University, estimated Rojava's economic output at that time to be 55 percent of Syria's gross domestic product.

Trade and investment

The production of crude oil and agricultural goods in Rojava exceeds demand; export goods are in particular crude oil , cotton and food ( wheat , sheep products ); Import goods are in particular industrial consumer goods and auto parts. Foreign trade and humanitarian assistance from the outside is made difficult by the total embargo of Turkey against Rojava. In general, Rojava solicits international investments, both in the form of donations for the development of community projects and as classic investments.

Oil production in Rojava

In cooperation with the Syrian government of Assad, the PYD's strategy also included maintaining control of the oil fields in the far north-east of Syria, which are mainly in operation in the small town of Rmeilan, near the PYD stronghold al-Malikiya (Dêrik) were. The large oil fields in northeast Syria thus remained under the control of a de facto alliance of the Assad regime and the PYD-led autonomous Kurdish administration. The Wall Street Journal correspondent Sam Dagher quoted representatives from the PYD-controlled part of Hasakah, according to which the oil fields in this region were producing 40,000 barrels a day under the supervision of the YPG . This oil was sold to local Arab tribal organizations for around $ 15 a barrel. The crude oil was then processed into diesel and gasoline through allegedly around 3,000 makeshift furnaces located in the area, which were sold to dealers for around $ 40 a barrel. One operator was quoted as saying that eight barrels of crude oil would produce six barrels of products in this way. According to Jihad Yazigi, editor of the Syrian business paper The Syria Report , a daily sales volume of 50,000 barrels of oil could secure the livelihood of around two million people. Since the PYD was responsible for distributing all fuels in the province of al-Hasakah, it was able to stop the black market and sell gas or heating oil at prices set by the state - that is, relatively low prices for the population in the region. Although the oil fields in Syria were more often fought over during the years of civil war, oil production was always quickly resumed. This was made possible because the local workers mostly remained the same and initially worked as Syrian government employees, in the meantime as employees of the radical Islamist Nusra Front and later, among others, employees paid by the IS. In both Syria and Iraq, oil smuggling worked across ideological and military borders.

Infrastructure and traffic

The public infrastructure in what is now Rojava was deliberately neglected by the Arab nationalist Ba'ath regime before the civil war . In the canton of Kobanê, the civil war also led to considerable destruction in the battle for Kobanê . The establishment of public infrastructure across all areas is the priority of the Rojava administration. Since 2016, exemplary projects have been presented on the “Rojavaplan” website.

In contrast to other public infrastructure, the road network in the area of today's Rojava was well developed. The only airport in the Rojava area is Qamishli Airport , it is controlled and operated by the Syrian central government. The Rimelan and Minakh military airfields are under Kurdish control .

media

Independent and Kurdish-speaking media were banned in Rojava until the beginning of the civil war. After the Syrian troops withdrew from Rojava and the Kurds took over the government function, the working environment for the media became freer. The media in Rojava have more rights than in other parts of Syria and the international press is welcome. In August 2013 the Free Media Union (YRA) was founded, where the media have to apply for a license in order to be allowed to start their work. The majority of the media is very politicized, and there is a split between media that are close to the PYD and media that are close to the largest Kurdish party in Iraq, the KDP. There are also reports of arrests and expulsions, mainly of journalists, who are attributed to the opposition, but the duration of the arrests is short and no one remained in custody until the end of 2015.

The following is a selection of the media available in Rojava:

- Ronahi TV and Ronahi newspaper with a circulation of 10,000

- Zagros TV

- Bûyerpress, a newspaper that appears in Kurdish and Arabic, was founded on May 15, 2015.

- Arta FM radio

- Rudaw's license was revoked in August 2015 to report from the Cizre Canton in Rojava.

schools

Under the Baath regime, the school system was characterized by purely Arabic-speaking public schools, supplemented by Assyrian church private schools. In the summer of 2015, the Rojava administration introduced bilingual teaching in Kurdish and Arabic in public schools . The endeavor to gradually revise the curricula in the public schools, which are shaped by Ba'ath ideology, is characterized by complex negotiations between the Syrian central government, which basically continues to pay the teachers' salaries, the Rojava administration, which wants to displace the Ba'ath ideology, and the Assyrian community, to whose church private schools Kurdish and Arab parents now also want to send their children.

None of the universities in Syria that existed when the civil war began in 2011 is located on the territory of today's Rojava. In September 2014, the Mesopotamian Academy of Social Sciences in Qamishli began teaching as a new university . Other such academies with different subject orientations are in the foundation or planning stage. In August 2015, the University of Afrin in Afrin, designed as a classic university , began teaching.

In July 2016, another university was opened in Qamishlo with Rojava University. This includes the faculties of medicine, engineering, classical sciences and art and human sciences.

Militias

Rojava's armed forces are the PYD-affiliated People's Defense Units (YPG / YPJ ). In the articles of association they are referred to as the national institution of all three cantons. Their relationship with the army of the central government of Syria should therefore be determined by Rojava's laws. They are closely supported by the allied Christian Syrian-Aramaic Sutoro militias and FSA brigades such as u. a. Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa within the Burkān al-Furāt Alliance and through the PKK and MLKP . For a long time, the most important opponent was the terrorist organization Islamic State (IS), but since the Afrin offensive, Turkey in particular has developed into an opponent for the militias represented in Rojava. Since the defense of Kobanê in September 2014, the YPG have been supported by air strikes by the US-led international coalition . Since the fight over Kobane, the USA has begun to supply the Rojavas militias, which are involved in the fight against IS, with weapons. During the battle for Kobane they were supported by Peshmerga from the autonomous region of Kurdistan in Iraq .

On October 10, 2015, the YPG formed a military alliance with the Sunni-Arab Army of Revolutionaries (Jaish ath-Thuwwar) , the Sunni-Arab Shammar tribal militia Quwat as-Sanadid and the Assyrian-Aramaic Military Council of Assyrians (MFS), which under the name of Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) jointly with the US-led international coalition against IS in Syria. The anti-IS coalition also supports the militias represented in the Syrian Democratic Forces with arms deliveries.

Judicial system

In Rojava, the administration is trying to get international recognition of its courts because of the fact that it holds many foreign IS fighters as prisoners. Because their courts have not yet been internationally recognized, the handover of ex-IS fighters to their countries of origin is difficult or even impossible (as of July 2018). For example, the PYD has abolished the death penalty and the longest sentence is life, which means a 20-year prison sentence. It also tries to ensure that religions have equal rights in court, and so Christians can swear by the Bible and Muslims on the Koran in court .

IS tribunals

In the trials with IS fighters, the judges seek reconciliation. Last year, for example, amnesties were negotiated for 80 IS fighters in order to encourage other IS fighters to surrender to the SDF. The penalties for ex-ISIS fighters can be very low if they surrendered themselves and were, for example, minors when they joined ISIS.

But there is also criticism of the judicial system. So far there are no lawyers who speak up for the accused and no courts of appeal. In addition, the judges remain anonymous.

Detention centers

In 2015 the administration in Rojava started working with international organizations like Geneva Call to better run their prisons. The prison guards are said to have received training from Geneva Call. The prisons are called academies because the focus is on reintegration into society.

Human rights situation

For most of Rojava's population, the human rights situation has improved significantly after taking over government, but reports of human rights violations continue to exist.

Women as well as ethnic minorities are now more involved in politics. Teaching in the respective mother tongue is also encouraged. During the Assad government, the state offered classes only in Arabic. Underage marriages and polygamy, as was common during the Assad government, were also banned. Anyone who marries a second wife can be imprisoned for 1 year and has to pay a fine.

In a 2014 report, the human rights organization Human Rights Watch raised serious allegations against the ruling PYD and the YPG, including arbitrary arrests of political opponents, mistreatment of prisoners, unsolved kidnapping and murder cases, and the use of child soldiers as war crimes . However, HRW also makes it clear in the report that the human rights violations proven by the PYD are far less blatant and widespread than those documented by the Syrian government and other rebel groups since 2011.

In August 2015, the Kurdish television broadcaster Rudaw Media Network urged the PYD to refrain from restricting press freedom after the canton of Cizîrê had withdrawn his license.

After the YPG conquered the corridor between the Syrian cantons of Cizîrê and Kobanê, which was previously dominated by IS and where more Arabs than Kurds live, reports of expulsions of Arabs and Turkmens became loud. While the Turkish and Arab media and blogs in particular had reported on it, Western newspapers and broadcasters hardly took up the allegations. The YPG denied the allegations and spoke against it of offers that had been made to civilians from the combat areas in order to prevent IS from using them as living shields.

In October 2015, Amnesty International (AI) accused the US-supported YPG war crimes in the form of displacement or forced resettlement of the civilian population and the destruction of their villages and spoke of a real wave of expulsions of thousands, primarily non-Kurdish (especially Turkmen and Arab) residents after the YPG took their villages. In particular, what happened in Hassaka Province, where Kurds and Christians as well as Sunni Arabs lived. The expulsion was viewed by AI as a “targeted and coordinated campaign for collective punishment” by the YPG against villages in which the YPG perceived residents to have sympathized with IS or other non-state armed groups (such as the FSA). AI accused the Kurdish-led administration of abusing their power and disregarding international law in a way that equated to war crimes. In their allegations, AI relied on satellite images and eyewitness reports from dozens of residents in Hasakah and Raqqa provinces that the YPG threatened to request air strikes by the US-led alliance.

A YPG spokesman has denied the allegations, describing them as "arbitrary", "partisan" and "unprofessional" and further accused Amnesty International of fueling ethnic tensions between Kurds and Arabs. He claimed that many of the areas investigated were destroyed by ISIS and other terrorist organizations using mines and booby traps. He also suspected Amnesty's witnesses to be complicit in ISIS. Finally, he pointed out alliances with Arab militias in the villages.

In a report from March 2017, the UN Human Rights Council also rejected the allegations of ethnic cleansing. Although isolated (sometimes temporary) resettlements were necessary due to mines and self-made explosive devices, there is no evidence that the cantonal governments took action against Arab communities, nor that the “demographic composition of the areas they control through acts of violence against certain ethnic groups systematically changed ”.

Course of war

The middle canton was almost completely destroyed in the course of the battle for Kobanê in September 2014 by the terrorist organization Islamic State (IS), but was held after months of fighting and the IS was pushed back.

In February 2015, the YPG and its allies, supported by air strikes by the US-led international coalition, began a counter-offensive with the aim of capturing the city of Tall Abyad in order to interrupt the IS supply route from the Turkish border town Akçakale to the Syrian IS capital Raqqa to connect the two cantons of Kobanê and Cizîrê. On June 16, 2015, the YPG announced it had taken control of Tall Abyad.

As a result of the fighting that broke out in northern Syria in June 2015, according to UNHCR, over 23,000 people from the Syrian governorate of Ar-Raqqa fled to Turkey, over 70% of whom were women and children. Shortly after the complete expulsion of IS from Tall Abyad and the surrounding area, thousands of refugees returned.

At the end of December 2015, the SDF , an alliance of the Kurdish YPG with Arab militias, liberated the Tischrin Dam from IS and took control of the foreland of the dam on the west bank of the Euphrates.

On February 13, 2016, Turkey began bombarding Kurdish positions near the city of Azaz and the canton capital Afrin with heavy artillery after the SDF began to fight against Arab rebel groups supported by Turkey and recorded land gains (capture of Tall Rifaat and the Menagh military airfield ). The US government has repeatedly called on both Turkey and the Kurds to cease hostilities.

On February 19, 2016, the SDF freed the city of Ash-Shaddadi and the surrounding area south of al-Hasakah from the IS occupation in northeast Syria, supported by air strikes by the US-led coalition .

On 31 May 2016, the SDF started, supported by a small number of US - special forces and air strikes by the US-led coalition launched an offensive with the aim of liberating the city manbij and its surroundings from the IS. In order to prevent Turkish countermeasures, it was declared that the majority of the fighters involved were Arabs and not Kurds on the part of the SDF. As part of the offensive, a siege ring was closed around the city on June 10th and the surrounding area was secured until June 17th. In a protracted house-to-house war, the SDF drove away the IS fighters and took full control of the city on August 12th. Thousands of refugees returned the very next day. Immediately after the Manbij offensive, the SDF marched west and north to connect with the canton of Afrin. But Turkey started a military offensive against IS and SDF with allied FSA groups in August 2016 , which ended with the capture of the city of al-Bab in February 2017.

After lengthy operations, the SDF was able to drive IS from its self-declared capital ar-Raqqa in mid-October 2017 with the help of the international coalition in the battle for ar-Raqqa . At the same time as the Syrian army, IS was displaced along the Euphrates and the long besieged city of Deir ez-Zor was liberated by the Syrian army at the end of November 2017. Since then, the Euphrates has been considered the demarcation line between the Syrian army and the SDF.

In mid-July 2017, it became known that the Turkish government was apparently gathering troops on the border with Syria in order to possibly use them against the canton of Afrin. The background to this should be an agreement with Russia, according to which the Russians and their allies would no longer defend the area against a Turkish attack. On January 20, 2018, Turkish armed forces, supported by FSA rebels, began their military offensive on Afrin and captured the city of Afrin on March 18, 2018 after the Rojavas government had evacuated the city.

On October 28, 2018, one day after a four-way meeting between the heads of government of Germany, Russia, France and Turkey, Turkey began bombing additional targets in northern Syria, whereupon the SDF temporarily suspended its offensive against IS and the US set up observation posts announced on the Syrian-Turkish border. Nevertheless, on December 12, Turkey announced its intention to invade Syria east of the Euphrates, at the expense of US losses. Barriers were dismantled at the border and military equipment was put into position. After the US announced a few days later that it would withdraw its troops from Syria within 60 to 100 days, Turkey postponed the attack until after the withdrawal. However, Turkey continued to gather troops on the border, and Russia offered to station soldiers from the Syrian government on the border with Turkey. On December 25, in view of the announced Turkish attack, the SDF handed over the city of Arima west of Manbij to troops of the Syrian government. On January 6, 2019, the USA announced that it would make the withdrawal of troops dependent on a Turkish security guarantee for the Kurdish fighters. In March, SDF troops captured the last IS-held areas in Syria.

At the end of July 2019, the Turkish government threatened to invade again after talks with the US about the establishment of a buffer zone had failed. According to the request of the Turkish government, this should be 30 to 40 kilometers wide; the USA rejected the invasion plans and, after further negotiations, decided, together with Turkey, to create a coordination center for the establishment of a security zone of still unknown size, which the Syrian government criticized as a violation of Syrian sovereignty. According to the Turkish Ministry of Defense, the zone should the return of Syrian refugees permit from Turkey, which is why in the time warned of the possibility of expulsions and "ethnic land consolidation" as they had already taken place in Afrin. From September, Turkish and US troops carried out joint patrols in the Syrian border area with Turkey. However, after a security zone had not been established, Turkish President Erdoğan announced another invasion on October 5, and on October 7, the US withdrew its own troops and announced that it would not support or commit to the planned military offensive to contribute. The offensive began on October 9th.

Rejection by Turkey

The Turkish President Erdoğan accuses the Rojava ruling PYD of ethnic cleansing of Arabs and Turkmens. He is taking up allegations of Syrian (including Islamist) rebel groups. Rami Abdulrahman, head of the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights , found these allegations unfounded in an interview conducted by the Society for Threatened Peoples , while Amnesty International documented that the YPG had committed war crimes against and expulsions of the non-Kurdish population.

The background to the allegations is above all the conflict between the Republic of Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), in which Turkey has been fighting for decades against the PKK, which is allied with the PYD. Turkey fears a strengthening of the PKK in the region.

In the Syrian civil war, the Turkish government was not a direct party to the war, but its main political goal is the overthrow of the Syrian government. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights accuses Turkey of supporting Islamist groups that are fighting not only the Syrian government but also the administration of Rojava established by the PYD.

Turkey has long been calling for the creation of a "protection zone" in the Syrian border areas and is therefore in a direct conflict of interests with the PYD and its territorial claims, known as "Rojava", in northern Syria. Two weeks after the Kurds took Tall Abyad, Turkey increased its military presence along the border. Speculations that Turkey would set up a buffer zone up to 40 kilometers deep in the areas between Jarabulus and Azaz that had been held by IS up to now were sparked by President Erdoğan when he immediately stated the goal of preventing a Kurdish state in northern Syria, "Cost what it may". As a result, ISIS began to mine its border with Turkey and dig trenches. Although the largest ethnic groups in the area in question are not Kurds, but Arabs and Turkmens, the PYD announced that it would consider Turkish troops as occupation troops in these areas previously held by IS and want to fight them if they intervene without a UN mandate. Furthermore, the PKK leadership threatened Turkey to wage war on its entire national territory if Turkey intervened in Rojava. The US ambassador to Ankara, John Bass, made the US position clear, according to which IS is the common enemy and everyone who has a border with IS must fight against it.

With its two military offensives ( Euphrates Shield and Operation Olive Branch ) in northern Syria, Turkey attacked IS and YPG areas. After the capture of Afrin, President Erdoğan emphasized that the YPG and SDF would cleanse the entire border from Manbidsch or create a corridor through Operation Peace Source.

Future of Rojava

From the beginning, despite the support of the Syrian Kurds by the USA, the existence of Rojava was endangered. This threat became acute with the announcement and implementation of the withdrawal of US troops from Syria in 2018/2019. In view of this situation, there were negotiations in 2018/2019 between the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and the central government in Damascus on the design of the post-war order in the north-east of the country. Some points of the Kurdish offer to the central government in Damascus were announced in mid-January 2019. They include, among other things, the “protection of the sovereignty of the state of Syria” and the formation of a “democratic republic”, of which the Kurdish plan includes the autonomous administration as a part.

In addition, the Kurdish offer from January 2019 provided:

- The representatives of the Autonomous Administration are to become part of the National Assembly.

- The flag of the Autonomous Administration is to be hoisted together with the national flag of Syria.

- The Autonomous Administration should be allowed to maintain its own diplomatic relations as long as they are in line with the interests of the Syrian nation-state and the constitution.

- The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) are to be integrated into the Syrian national army and form part of the border protection.

- Internal security forces are said to be under the control of regional assemblies in the autonomous region.

- In the Syrian regions of the Autonomous Administration, the mother tongue is to be established as the language of education, while Arabic is to be retained as the official language.

- Faculties for history, culture, language, literature and other subjects are to be set up where teaching is to take place in the respective regional language.

- All natural resources should be distributed “fairly and equally” across the entire country.

On January 23, 2019, Russia suggested applying the Adana Agreement to the areas east of the Euphrates, which can be interpreted as authorizing Turkey to take cross-border action against "Kurdish terrorists" in northeastern Syria, with Syria tolerating the action. As early as April 2019, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation took the view that Russia had “considerable indirect power to define the framework conditions for Kurdish autonomy within the Syrian nation state”.

See also

literature

- Elke Dangeleit: Rojava: Proclamation of a Kurdish-Syrian "Democratic Federation" . Telepolis, March 20, 2016.

- Elke Dangeleit: The Rojava model . Telepolis, October 12, 2014.

- Dr. Bawar Bammarny: The Legal Status of the Kurds in Iraq and Syria . In: Constitutionalism, Human Rights, and Islam After the Arab Spring. Oxford University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0-19-062764-5 , pp. 475-495.

- Thomas Schmidinger : War and Revolution in Syrian Kurdistan. Analysis and voices from Rojava. Mandelbaum Verlag, Vienna, fourth, expanded and updated edition 2017 (first 2014), ISBN 978-3-85476-636-0 .

- Thomas Schmidinger : Battle for the Kurdish Mountain - Past and Present of the Afrin Region . Bahoe Books , Vienna 2018. ISBN 978-3-903022-84-3 .

- Ismail Küpeli (Ed.): Kampf um Kobanê - Struggle for the future of the Middle East , edition assemblage, Münster 2015, ISBN 978-3-942885-89-8 .

- Wes Enzinna: Utopia in War , Philosophie Magazin 3/2016.

- Anja Flach / Ercan Ayboğa / Michael Knapp: Revolution in Rojava. Women's movement and communalism between war and embargo , 3rd updated edition, VSA Verlag, Hamburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-89965-736-4 .

- Oso Sabio: Rojava. The alternative to imperialism, nationalism and Islamism in the Middle East. , Unrast Verlag, Münster 2016, ISBN 978-3-89771-058-0 .

- Doc Sportello (Ed.): Rojava - Has the uprising come? Three texts by Gilles Dauvé, Il Lato Cattivo and Becky, translated from the French by Doc Sportello. Bahoe Books , 2nd updated edition, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-903022-14-0 .

- Matthias Hofmann: Kurdistan from the beginning. Saladin Publishing House. Berlin 2019. ISBN 978-3-947765-00-3 .

Web links

- “Kurds become self-employed” , SZ online , March 17, 2016.

- Christian Wirth: "Apo" and dream dancers: Utopia in Rojava Libertarian municipalism

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Terry Glavin: "In Iraq and Syria, it's too little, too late" , http://ottawacitizen.com , / November 14, 2014. Query date: March 19, 2016.

- ↑ Kurds proclaim autonomous area , tagesschau.de, March 17, 2016

- ^ The war in Western Kurdistan and Northern Syria: The role of the US and Turkey in the Battle of Kobani , fourwinds10.net

- ↑ Mustafa Nazdar (pseud.), The Kurds in Syria , in: Gérard Chaliand (ed.), Kurdistan und die Kurden, Vol. 1, Göttingen 1988, ISBN 3-922197-24-8 , p. 400 f.

- ↑ Syria: The silenced kurds report by HRW from October 2006

- ↑ Syria: End persecution of human rights defenders and human rights activists ( Memento of March 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Article of December 7, 2004 from amnestyusa.org

- ^ Kurds declare an interim administration in Syria. www.reuters.com, November 12, 2013.

- ^ "Kurdish Autonomy Plans" , Neue Zürcher Zeitung , March 17, 2016.

- ^ Rojava: Proclamation of a Kurdish-Syrian "Democratic Federation" , Telepolis , March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Autonomy plans isolate Kurds" , tagesschau.de, March 17, 2016.

- ^ Syrian Kurds open diplomatic mission in Moscow. The Telegraph, February 10, 2016.

- ^ Syrian Kurds inaugurate representation office in Sweden , Ara News, April 18, 2016

- ^ Syrian Kurds open unofficial representative mission in Paris . Al Arabiya. May 24, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ [1] , Evrensel, May 7, 2016.

- ^ Rojava agency in Germany. Young World, May 9, 2016.

- ↑ [2] , Prague Monitor, April 3, 2016.

- ↑ http://www.cbssyr.org/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf ( Memento from March 10, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Onur Burçak Belli: Sad winners . Zeit Online from March 22, 2014, accessed on March 22, 2014

- ↑ Rojava artık özerk , article in the Radikal from January 31, 2014 (Turkish)

- ^ Restructuring of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria , Civaka Awad, August 11, 2017

- ↑ The Siege Of Kobani: Obama's Syrian Fiasco In Motion , analysis by US political scientist David Stockman from October 11, 2014 (English)

- ^ Will Syria's Kurds benefit from the crisis? , BBC analysis by diplomatic correspondent Jonathan Marcus, August 10, 2012

- ↑ http://civaka-azad.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/info7.pdf Articles of Association of Rojava

- ^ A b Rodi Said: Syrians vote in Kurdish-led regions of north . In: US ( reuters.com [accessed July 28, 2018]).

- ^ A b Syrian Kurds in Rojava Vote for a Democratic System After ISIS . In: The Globe Post . September 23, 2017 ( theglobepost.com [accessed July 28, 2018]).

- ^ A b c Voting in the civil war: regional council elections in Rojava. Retrieved July 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Michael Knapp, 'Rojava - the formation of an economic alternative: Private property in the service of all' .

- ↑ http://sange.fi/kvsolidaarisuustyo/wp-content/uploads/Dr.-Ahmad-Yousef-Social-economy-in-Rojava.pdf

- ^ A Small Key Can Open a Large Door: The Rojava Revolution , 1st. 3rd edition, Strangers In A Tangled Wilderness, March 4, 2015: “According to Dr. Ahmad Yousef, an economic co-minister, three-quarters of traditional private property is being used as commons and one quarter is still being owned by use of individuals ... According to the Ministry of Economics, worker councils have only been set up for about one third of the enterprises in Rojava so far. "

- ↑ Efrin Economy Minister Yousef: Rojava challenging norms of class, gender and power . Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ↑ Flight of Icarus? The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria (PDF) International Crisis Group. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ↑ Zamana LWSL .

- ↑ Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency? . Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ^ Striking out on their own . In: The Economist .

- ^ Kurds Fight Islamic State to Claim a Piece of Syria . In: The Wall Street Journal .

- ^ Syrian Kurds risk their lives crossing into Turkey . Middle East Eye. December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ a b Mona Sarkis: The fight for oil in the Kurdish region? Retrieved August 4, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Syria's Economy - Administrative Institutions | Chatham House . In: Chatham House . ( chathamhouse.org [accessed August 4, 2018]).

- ↑ Raniah Salloum: Smuggling Channels of IS: The Oil Empire of the Islamists . In: Spiegel Online . September 25, 2014 ( spiegel.de [accessed August 4, 2018]).

- ↑ Rojavaplan . Rojava administration. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d Syria. Retrieved July 26, 2018 .

- ↑ www.karwan.tv: Ronahi TV ZINDÎ پەخشی راستەوخۆی - www.Karwan.TV. Retrieved July 17, 2018 (UK English).

- ↑ blid: “#SRFglobal” from March 1, 2018. Swiss Radio and Television SRF, March 1, 2018, accessed on July 17, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Syria. Retrieved July 26, 2018 (American English).

- ^ Kurdistan24: Syrian Kurds celebrate Kurdish Language Day . In: Kurdistan24 . ( kurdistan24.net [accessed July 18, 2018]).

- ^ Journalists' watchdog: PYD must let Rudaw work in Rojava . In: Rudaw . ( rudaw.net [accessed July 26, 2018]).

- ↑ David Commins, David W. Lesch: Historical Dictionary of Syria . Scarecrow Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8108-7966-9 , pp. 239 ( google.com [accessed May 10, 2016]).

- ^ After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools. In: Al-Monitor. November 6, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2016 (American English).

- ^ Rojava schools to re-open with PYD-approved curriculum . Rudaw. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Kurds introduce their own curriculum at schools of Rojava . Macaw News. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ Hassakeh Schools Switch to Kurdish Language Education. In: www.newsdeeply.com. Retrieved May 10, 2016 .

- ↑ A war over school books determines Syria's future . The world. May 20, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS 'Backyard . New York Times. November 29, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Syria's first Kurdish university attracts controversy as well as students . Al monitor. May 18, 2016. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved on May 19, 2016.

- ↑ Kurdistan24: Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability . In: Kurdistan24 . ( kurdistan24.net [accessed July 18, 2018]).

- ↑ Julian Borger, Fazel Hawramy: US providing light arms to Kurdish-led coalition in Syria, officials confirm. September 29, 2016, accessed November 6, 2018 .

- ^ Kurds unite as Iraqi Peshmerga join battle in Kobane . In: ABC News . October 31, 2014 ( net.au [accessed November 6, 2018]).

- ^ Declaration of Establishment by Democratic Syria Forces. October 15, 2015, archived from the original on February 24, 2016 ; Retrieved November 4, 2015 .

- ↑ Fight against terrorist militia: Syrian Kurds and Arabs ally against IS. In: The world. October 12, 2015, accessed November 4, 2015 .

- ^ Anti-ISIS Coalition: We will continue to arm, train, SDF in Syria . In: The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com . ( jpost.com [accessed November 6, 2018]).

- ↑ Rodi Said: SDF to study any request to hand over British IS militants captured ... In: US ( reuters.com [accessed July 26, 2018]).

- ↑ a b c d e Syria’s Kurds Put ISIS on Trial With Focus on Reconciliation . In: Haaretz . May 8, 2018 ( Haaretz.com [accessed July 26, 2018]).

- ↑ a b North Syria: Sad winners . In: ZEIT ONLINE . ( zeit.de [accessed October 29, 2018]).

- ^ Zana Omar: Syrian Kurds Get Outside Help to Manage Prisons . In: VOA . ( voanews.com [accessed July 26, 2018]).

- ↑ Sardar Mila Drwish: The Kurdish school curriculum in Syria: A Step Towards Self-Rule? In: Atlantic Council . ( atlanticcouncil.org [accessed October 29, 2018]).

- ↑ Syrian Kurds tackle conscription, underage marriages and polygamy - ARA News . In: ARA News . November 15, 2016 ( aranews.net [accessed October 29, 2018]).

- ↑ Human Rights Watch: Under Kurdish Rule - Abuses in PYD-Run Enclaves of Syria , Annual Report June 19, 2014, accessed July 7, 2015

- ↑ Rudaw blasts PYD ban in Rojava as like 'North Korea' .

- ↑ a b c d Amnesty International accuses Kurds of expelling Arabs ( memento from October 14, 2015 on WebCite ) , Telepolis, October 13, 2015, by Peter Mühlbauer .

- ↑ Ethnic cleansing charged as Kurds move on Islamic State town in Syria ( Memento from October 14, 2015 on WebCite ) , mcclatchydc.com, June 13, 2015, by Mousab Alhamadee and Roy Gutman.

- ↑ Erdogan fears fall of Syria's Tell Abyad ( Memento from October 15, 2015 on WebCite ) (English), al-monitor.com, June 14, 2015, by Fehim Taştekin.

- ↑ Kurdish forces deny claims of abuse in towns They liberate from IS ( Memento of 15 October 2015 Webcite ) (English) The Sydney Morning Herald, June 19, 2015 by Ruth Pollard.

- ↑ a b Syria: Amnesty International accuses Kurds of displacement - PYD fighters supported by the USA are said to have forced thousands of civilians to flee and destroyed villages in northern Syria. Amnesty speaks of a war crime ( memento from October 14, 2015 on WebCite ) , zeit.de, October 13, 2015 (Zeit Online, Reuters, ap, ces).

- ↑ a b c Syria: Amnesty accuses Kurdish militia of expulsions ( memento from October 14, 2015 on WebCite ) , spiegel.de, October 13, 2015 (anr / Reuters / dpa).

- ↑ Amnesty International accuses Kurdish YPG of war crimes ( Memento from October 14, 2015 on WebCite ) (English), al-monitor.com, October 13, 2015, by Amberin Zaman.

- ↑ a b 'We had nowhere to go' - Forced displacement and demolitions in Northern Syria ( Memento of 15 October 2015 Webcite ) (English), Amnesty International, Index number: MDE 24/2503/2015, October 12, 2015 ( PDF ( Memento from October 15, 2015 on WebCite ). See also: "We had nowhere else to go": Forced displacement and demolitions in northern Syria (English; video: 7:43 min.), YouTube, published on the YouTube channel Amnesty International on October 13, 2015.

- ↑ a b c Report from Amnesty International - Satellite images pollute the Kurdish militia - Crimes are committed on all sides in Syria. Now human rights activists are also accusing Kurds of serious offenses. Eyewitnesses reported how the PYD party abused its power and violated international law ( memento from October 14, 2015 on WebCite ) , n-tv.de, October 13, 2015 (n-tv.de, kpi / dpa).

- ↑ Revenge for alleged IS support? - The human rights organization Amnesty International (AI) raises violent allegations against the Syrian Kurdish militia YPG. Entire villages and cities were systematically destroyed. It is a "targeted and coordinated campaign for collective punishment" of the inhabitants of the villages previously controlled by the terrorist militia Islamic State (IS) ( memento of October 16, 2015 on WebCite ) , orf.at, October 13, 2015.

- ↑ Amnesty: US-backed Syrian Kurds May Have Committed War Crimes ( Memento of 16 October 2015 Webcite ) (English), voanews.com, October 13, 2015.

- ↑ Syria Kurds denounce Amnesty 'war crimes' report .

- ↑ Human rights abuses and international humanitarian law violations in the Syrian Arab Republic, 21 July 2016–28 February 2017

- ↑ Mireille Court: From Le Monde diplomatique: Democratic enclave in Northern Syria . 15th September 2017.

- ↑ Casper Schliephack: decisive battle between the Kurds and IS for the Tall Abyad lifeline . In: Deutsch Türkisches Journal , March 9, 2015, accessed on June 14, 2015.

- ↑ Peter Mühlbauer : Kurdish commander reports control of Tall Abyad . heise online from June 16, 2015, accessed on June 16, 2015

- ↑ Le groupe EI perd Tall Abyad, son plus grand revers en Syrie ( Memento from July 5, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). Liberation on June 16, 2015, accessed June 16, 2015

- ↑ Fighting in Northern Syria: 23,000 flee to Turkey. ( Memento of June 17, 2015 in the Internet Archive ): UNHCR report , June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ↑ Syria: Thousands of refugees return home as Kurds capture more territory from Isis [Photo report ] . 23rd June 2015.

- ^ Syrian Refugees Return to Tal Abyad .

- ↑ Success of the Kurds against IS disturbs Turkish interests heise online from December 27, 2016, accessed on February 21, 2016

- ^ Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com): Turkey remains stubborn in Kurdish policy - DW - 02/14/2016 .

- ↑ Turkish army bombs Syrian-Kurdish enclave Afrin. Heise.de from February 20, 2016, accessed on February 21, 2016

- ↑ Obama calls on Turkey and the Kurds to show restraint. ( Memento from February 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Deutschlandfunk from February 20, 2016, accessed on February 21, 2016

- ↑ YPG conquers IS bastion in Syria. Euronews of February 19, 2016, accessed on February 21, 2016

- ↑ SDF take control on Menbej city Syrian Observatory for Human Rights on Facebook, accessed on August 7, 2016

- ↑ [3] ORF news, accessed on August 14, 2016

- ↑ Thousands return to the liberated Syrian city of Manbij Deutsche Welle, accessed on August 14, 2016

- ↑ Hannes Heine and Muhamad Abdi: "Turkey apparently wants to occupy Kurdish territory" Tagesspiegel from July 20, 2017

- ↑ Afrin: The capture of an abandoned city heise.de from March 18, 2018

- ↑ Turkish army bombs US-backed Kurdish militia . Time online. October 28, 2018. Accessed October 31, 2018.

- ↑ US Army sets up observation posts in Syria . orf.at . November 22, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ Kurdish fighters in Syria. Turkey wants to attack again . taz.de . December 13, 2018. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- ^ Turkish military offensive: President Erdoğan wants to "cleanse" northern Syria of IS and YPG . Time online. December 21, 2018. Accessed December 21, 2018.

- ↑ Turkey masses troops near Kurdish-held town in northern Syria . In: The Guardian .

- ↑ Russia offers to deploy border guards of the regime on the borderline between the two rivers and a delegation of SDF arrives in Moscow to discuss it and discuss the future of east Euphrates . In: SOHR , December 23, 2018.

- ↑ Syrian army reinforced close to front with Turkish-backed forces . In: Reuters . December 25, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ↑ Trump Adviser: US to Leave Syria Once IS Beaten, Kurds Safe . In: New York Times . January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ↑ Isis caliphate defeated: Victory declared as Islamic State loses last of its territory . In: The Independent . March 23, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ↑ Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announces offensive in Syria . In: ZEIT ONLINE . July 26, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ↑ US Secretary of Defense warns Turkey of military offensive . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ Turkey and the USA are planning a joint operation center for the security zone . In: ZEIT ONLINE . August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ Syria condemns US and Turkey plan for buffer zone . In: ZEIT ONLINE . August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ There must be no second Afrin . In: ZEIT ONLINE . August 9, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ USA and Turkey start patrols . In: Der Tagesspiegel . September 8, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ↑ Turkey and USA start second joint patrol in northern Syria . In: ZEIT ONLINE . September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ↑ Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatens military operations in Syria . In: ZEIT ONLINE . October 5, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ↑ USA clear the way for Turkish military offensive . In: ZEIT ONLINE . October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ↑ Turkey begins offensive against Kurds . In: ZEIT ONLINE . October 9, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ↑ Ethnic cleansing claims as Kurds take fight to Islamic State in Syria. : Article on The Sydney Morning Herald , June 14, 2015, accessed July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Syria: Kurdish YPG accused of 'ethnic cleansing' of Arabs in battle for Tel Abyad , International Business Times, June 15, 2015 (English)

- ↑ “There can be no question of 'ethnic cleansing' in Til Abyad against the Arabs or Turkmens.” ( Memento from July 15, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), Society for Threatened Peoples, June 26, 2015

- ↑ Turkey and the USA at odds over protection zones at the border , Tagesspiegel, November 23, 2014, accessed on July 7, 2015

- ↑ Turkey pulls tanks together at the border , Tagesspiegel, July 3, 2015, accessed on July 7, 2015

- ↑ Jordi Tejel, Jane Welle: Syria's kurds history, politics and society , 1st publ. Edition, Routledge, London 2009, ISBN 0-203-89211-9 , pp. XIII-XIV, p. 10.

- ↑ Are Turkish troops marching into Syria? : Welt.de, June 30, 2015, accessed July 8, 2015

- ↑ Karayılan: 'Rojava'ya müdahale ederlerse biz de onlara müdahale ederiz' Rojeva Kurdistan, June 29, 2015, accessed on July 8, 2015

- ↑ Bayık: Rojava'ya müdahale olursa Türkiye'de savaş başlar ( Memento from July 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Yüksekova Haber, July 3, 2015, accessed on July 8, 2015

- ↑ US committed to 'unified' Syria, in communication with PYD Hürriyet Daily News, July 3, 2015, accessed July 8, 2015

- ↑ Syria: Turkish Invasion or Agreement with Damascus? Since the US decision to withdraw, the struggle over northern and eastern Syria has come to a head . Rosa Luxemburg Foundation , April 2019.