Standard Chinese

|

Standard Chinese Mandarin 标准汉语 / 標準漢語 - Biāozhǔn Hànyǔ 普通话 / 普通話 - Pǔtōnghuà 国语 / 國語 - Guóyǔ 华语 / 華語 - Huáyǔ |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

People's Republic of China , Republic of China (Taiwan) , Singapore | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

zh (Chinese languages) |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) chi (Chinese languages) | ( T ) zho (Chinese languages) |

| ISO 639-3 | ||

Standard Chinese or (Modern) Standard Chinese (technical language: (現代) 標準 漢語 / (现代) 标准 汉语 , (Xiàndài) Biāozhǔn Hànyǔ ) is the standard variety of Chinese , the official language of the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) and one of the four official languages Singapore .

The standard language is based in its form on the Peking dialect of Mandarin (North Chinese). The official definition is: "The Beijing pronunciation as standard pronunciation, North Chinese as the basic dialect, the relevant modern báihuàwén works as standard grammar."

There are increasing numbers of younger Chinese and residents of larger cities who speak only or predominantly the standard language and none of the Chinese dialects. In large part, this is the result of efforts by the governments of the People's Republic and Taiwan to establish standard Chinese as a common language. According to a survey by the Ministry of Education in 2014, however, only 7% of the population of the PRC speak clear and fluent standard Chinese, and 30% are not able to communicate in this language at all.

The spelling of Chinese is also largely standardized. The Chinese written language báihuàwén ( 白話文 / 白话文 - "about: everyday writing") is based - unlike the classic written language wényánwén ( 文言文 - "about: literary writing ") - on modern colloquial language. Before that, texts in the classical written language, from which the spoken language had completely differentiated, had the highest prestige in society. The elimination of this diglossia situation in Chinese society, i.e. the establishment of the báihuàwén as the primary written language, only took place after the fall of the Qing dynasty at the beginning of the 20th century as a result of social upheavals in the May Fourth Movement .

In addition to Standard Chinese , there are other Chinese languages that are often referred to as dialects of Chinese. This designation primarily reflects the low status that these languages are accorded, but also the fact that they (apart from Cantonese ) do not have a generally accepted written language. Linguistically, a distinction is made between at least six languages or dialect groups of Chinese, which in turn are by no means uniform. However, since the founding of the People's Republic of China at the latest, learning the standard language has been propagated as a second language and taught in schools.

Designations

In Chinese itself, there are already several terms for the standard language, different in meaning: Pǔtōnghuà ( 普通话 or 普通話 , literally "normal lingua franca ") is the name commonly used in the People's Republic of China for the standard language as taught in schools and is used in official texts. In Taiwan the term Guóyǔ is used ( 国语 or 國語 "national language"). Among the overseas Chinese , especially in Southeast Asia, Standard Chinese is known as Huáyǔ ( 华语 or 華語 "Chinese language").

Běifānghuà (北方 话 or北方 話 , literally 'dialects of the north'), on the other hand, is the collective term for the dialects of the north on which the standard language is based. Individual dialects in the northern region show regional differences to the standard language, but these are less than in southern dialects.

The name Hànyǔ ( 汉语 or 漢語 , literally “language of the Hàn ”), which is commonly used in Chinese colloquial language , is often used synonymously with “Chinese” or “Standard Chinese”. However, not all Han Chinese speak the standard dialect as their mother tongue. Instead, Hànyǔ refers to all Han Chinese dialects . Hakka speakers emphasize that their dialect should also be referred to as Hànyǔ , as the grammar of the Hakka language is closest to classical Chinese texts.

The terms Peking dialect ( 北京 话 or 北京 話 Běijīnghuà or 北京 方言 Běijīng fāngyán ) or Peking Chinese are also imprecise. It is used as a derogatory term in Taiwan by those who advocate Taiwan's independence and believe that Taiwanese should be the national language of Taiwan.

The term Mandarin for the Chinese language is used in older German-language publications and is used more frequently again today under the influence of English. This word is derived from the Portuguese word mandarim (from the Malay menteri and the Sanskrit word mantrin- ), which means “counselor”, “ minister ”. This is the translation of the Chinese word Guānhuà ( 官 话 or 官 話 ), which can be translated literally as the “language of the mandarins” (the imperial officials ). Guānhuà is considered archaic by the Chinese today , but linguists sometimes use it as a term that includes all dialects and variations of North Chinese (not just Pǔtōnghuà and Guóyǔ).

standardization

The standardized forms of Chinese, Pǔtōnghuà and Guóyǔ, use the pronunciation of the Peking dialect as a basis without its regional specifics. Even so, there are regional variations in pronunciation , for two reasons:

- In the vast geographic area where Standard Chinese is a mother tongue, differences become apparent when moving from one place to another. The differences can be compared with the dialects and accents of the German language.

- People for whom Standard Chinese is a second language (i.e. their mother tongue is another of the Chinese languages) give their pronunciation a very strong regional accent. Taiwan residents, for example, often have a greater and more consistent deviation from standard Chinese, which the education authorities have defined as the standard language . Examples are the initials zh and sh in Hanyu Pinyin (e.g. si instead of shi, zong instead of zhong).

From an official point of view, there are two standard Chinese languages: that of the People's Republic of China (Pǔtōnghuà, "standard language") and that of Taiwan (Guóyǔ, " national language "). Officially, Pǔtōnghuà includes pronunciations from different regions, while Guóyǔ is at least theoretically based only on the Beijing pronunciation. In principle, there was no big difference between Pǔtōnghuà and Guóyǔ in the 1950s. But some have emerged over time. For example, 危 , 期 , 帆 , 椰 are pronounced in Pǔtōnghuà in the 1st tone, in Guóyǔ in the 2nd tone. 液 is pronounced as yè in Pǔtōnghuà and yì in Guóyǔ. It is interesting that the pronunciation of some characters in Guóyǔ is the same as in the Beijing dialect, but not in Pǔtōnghuà. For example, 和 with the meaning “and” is pronounced hé in Pǔtōnghuà and hàn in Guóyǔ. The later Beijing pronunciation is no longer used by the younger generation in Beijing and other parts of mainland China because of the implementation of Pǔtōnghuà, but it is used in Taiwan.

Not all variants of standard spoken Chinese are understandable everywhere. SIL International writes:

History of origin

There is a consciousness in China that the common national language and the individual dialects or regional languages in China descend from the language of the Han Chinese from prehistoric times and thus have the same origin.

Most of the Chinese who live in northern China, Sichuan and in a wide range from Manchuria in northeast China to southwest ( Yunnan ) have various northern Chinese dialects as their mother tongue. The predominance of these dialects in northern China is due to the large plains of this region. In the south, on the other hand, the rivers-rugged mountainous region has promoted linguistic diversity. The fact that a northern Chinese dialect is spoken in the mountainous Sìchuān is due to a plague epidemic that depopulated the region in the 12th century. It was later repopulated by northern Chinese people.

In spite of the linguistic diversity that still prevails in China today, one can name a national language in every Chinese dynasty ; these are the languages of the capital cities. However, it can be assumed that the degree of prevalence in the individual social classes was not particularly high, and there was no systematic language planning .

Only a relatively small number of officials, traders, and traveling scholars used the standard language. The reasons for the increase in the demand of the common population for a common national language are suspected to be the increase in supra-regional communication and mobilization after the beginning of industrialization with the onset of the Western powers in the Opium Wars at the end of the 19th century.

In the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty , the term Guanhua ( 官 話 , guānhuà - "language of officials, Mandarin") appeared for the general standard language (from today's perspective "Old Mandarin" 古 官 話 , Gǔ guānhuà or "Early -Mandarin “ 早期 官 話 , called zǎoqí guānhuà ). At that time, the capital was relocated to Beijing, and therefore the northern Chinese languages gained prestige. That is why the Guanhua is based on the northern regional languages .

At the end of the Qing Dynasty , with a strengthening of national consciousness after the humiliation of the lost Opium Wars in 1840 and 1856 and the lost war against Japan in 1894 , calls for a common language for the people were voiced, spoken by all parts of the population and in the should be uniform across the country.

One of the first Chinese who coined the term Putonghua (in German: "general language") was the linguist Zhu Wenxiong in 1906. The idea of a common national language was also supported by Li Jinxi , Qu Qiubai and Lu Xun and took on concrete dimensions in 1913 after the overthrow of the imperial government in the " National Conference on the Unification of Pronunciation " held by the Beiyang government , at which the pronunciation standard for a uniform national language was defined in detail. Because of a dispute between northern and southern linguists, a democratic decision was initially made in favor of the Beijing pronunciation with southern phonetic peculiarities, but in 1924 it was decided that the Beijing pronunciation should become the standard pronunciation.

The name Guoyu (in German: "National Language ") for a national language was also introduced at the end of the Qing Dynasty . It was from the Beiyang Government and the Government of the Guomindang used Taiwan uses this designation today still.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China , the "National Conference on Writing Reform" in 1955 continued to discuss the spread of the general Chinese language. Among other things, it was decided that the name Guoyu should be avoided out of respect for the other national minorities living in China and that the name Putonghua should be used instead .

The linguistic diversity is promoted overall, no dialects should be eradicated. However, the standard language was put on the agenda of national compulsory education in connection with the auxiliary phonetic transcription pinyin from Latin letters. In 1982 the state established the spread of the "nationally used common language" in the Chinese constitution, and the standard language is thus becoming more and more popular in large parts of China.

With Deng Xiaoping's “Journey to the South” in 1992 as a blow against the economically conservative forces and the opening of further special economic zones in the south of the country, a large number of non-Cantonese from other parts of China also come to southern China, for example Canton . Despite the assertiveness of their canton dialect, it became inevitable for the cantonese to use the general language to a greater extent.

Standard Chinese and Beijing dialect

It is a common misconception that standard dialect and the Beijing dialect are the same thing. It is true that the standard pronunciation and grammar of the language of instruction are based on the Beijing dialect, but the standard dialect is an artificial idiom, similar to written German. In the vast area from Manchuria in northeast China to Yúnnán in the southwest, it is the mother tongue in the broader sense, but these mother tongues differ more or less from standard Chinese in pronunciation, vocabulary, semantics and grammar.

As for the Beijing dialect proper, the retroflex initials ( zh-, ch-, sh-, r- ) are pronounced in accordance with standard Chinese, but an er ( 兒 / 儿 ) is often added to the syllable , often as a diminutive , or simply to denote nouns . This is not done in other regions of China, which is why the Beijing dialect is called éryīn ( 兒 音 / 儿 音 ). There are also a large number of words that are not used or not understood outside of Beijing. In addition, as in major German cities, Beijing has more than one local accent.

With the exception of these examples, the Beijing pronunciation is largely identical to that of standard Chinese. In general, it can be said that the further you get from Beijing, the greater the difference in pronunciation. The residents of the city of Tiānjīn also have a pronunciation that corresponds to standard Chinese.

In northeastern China, the j sounds often become g sounds or k sounds; likewise, people pronounce the r sounds differently.

In the southern parts of China, the retroflex initials of the standard dialect are not pronounced. For example, zh- becomes z- , ch- becomes c- , sh- becomes s- and r- sounds more like z- , especially for speakers whose mother tongue is Min (e.g. Taiwan, Fujian), Wu (e.g. Shanghai, Suzhou) or Cantonese (e.g. Guangdong, Hong Kong). In other areas no distinction is made between l and n , while in still other areas the ng tones are spoken like n tones.

The standard dialect knows the "light tone " for syllables that are pronounced too short and unstressed to have a recognizable tone. However, especially in the south, all syllables and their tones are pronounced clearly and differently.

phonetics

Consonants

Standard Chinese (both Putonghua and Guoyu) uses the following consonants (after Lee & Zee 2003):

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

dental / alveolar |

postalveolar |

alveopalatal / palatal |

velar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nasp | asp | nasp | asp | nasp | asp | nasp | asp | nasp | asp | nasp | asp | |

| Plosives | p | pʰ | t | tʰ | k | kʰ | ||||||

| Affricates | ts | tsʰ | tʂ | tʂʰ | tɕ | tɕʰ | ||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||

| Fricatives | f | s | ʂ | ɕ | x | |||||||

| Approximants | w | ɹ̺ | j | |||||||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||||||

- asp = aspirated ; nasp = not aspirated

- postalveolar, more precisely apico -postalveolar (<lat. apex "[tongue] Peak") = retroflex

- The two nasals / n / and / ŋ / are the only consonants that can close syllables (unlike in Cantonese )

Vowels

Standard Chinese has 21 vowels :

i, y, a, ə, u, ɤ

ai, au, ou, uo, ei (only in open syllable, i.e. CV)

ye, ie, ia, ua (in open and closed syllable, CV / CVN)

uə, iu (only in closed syllable, i.e. CVN)

(C : Consonant, V: vowel (s), N: nasal sound)

iau, uai, iou, uei (CV only)

A table with all phonotactic possibilities can be found in Article Pinyin .

Sounds

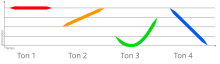

Standard Chinese, like all other Chinese languages, is a tonal language . A syllable can have one of the four tones or none at all. A different tone usually has a different meaning, but a syllable can only have one tone at a time, regardless of the mood of the speaker or the position of the word in the sentence; a rising pitch is not to be equated with a question and a falling pitch is not equated with a statement. The different tones are:

-

First tone ( high tone ):

- The pitch is constant and high. Example: mā (mother).

-

Second tone ( rising tone ):

- The pitch rises from the lower to the middle to the high pitch, similar to the intonation of a question in German. Example: má (hemp).

-

Third tone ( low or low-falling-rising tone ):

- The pitch sinks down from the middle level and usually rises again to the middle level. Example: mǎ (horse).

-

Fourth tone ( falling tone ):

- The pitch falls sharply downwards and the syllable is pronounced shorter with more affect, comparable to the German accentuation of a command (e.g. “go!”). Example: mà (rant).

The light tone , neutral tone , zeroth tone or fifth tone ( 輕聲 / 轻声 , qīng shēng - "light tone") is often treated separately: It sounds short and light and is therefore often not regarded as a separate tone. Most North Chinese dialects have polysyllabic words in which the second syllable is less pronounced than the first; see above. In pinyin this tone is marked by a point or not at all. Examples: 媽媽 / 妈妈 māma = mom and 爸爸 bàba = papa.

The pronunciation of the tones changes according to the rules of Tonsandhi . The most common occurrence of tone sandhi is when the first syllable of two consecutive syllables in the third tone is pronounced in the second tone. If three syllables follow one another in the third tone, it depends on regional habits and personal preferences whether the first syllable has a third or second tone.

With a number below 450 in standard Chinese, the number of syllables is relatively small. Each syllable is formed according to the pattern (optional) initial + vowel + (optional) nasal final . Not every syllable that could be formed according to this pattern is actually used. That is why there are only a few hundred syllables (and consequently, very pronounced homophony ). There is no m -authentication in standard Chinese, but there is in other "dialects", e.g. B. in the Hakka .

grammar

Loan words in standard Chinese

Manifestations

In the case of a borrowing, the phonemes of the model are replaced by phonemes of the borrowing language. In principle, Chinese has about the same number of phonemes as English, for example . It is characteristic, however, that consonant clusters from other languages have to be replaced with other phoneme sequences when borrowing into Chinese due to existing phonetic differences; the affected syllable must be segmented in Chinese. If you also want to fix the loanwords in Chinese in writing, the characters from your own script are normally used. Since the Chinese script is a syllable or morphemic script, it is often not possible to reproduce individual sounds in the script, only syllables. This type of borrowing from mostly European languages is often referred to as yinyi 音譯 / 音译 (phonetic borrowing). Examples:

- 幽默 youmo <English humor

- 邏輯 / 逻辑 luoji <English logic

Another special feature is that when borrowing from other Asian countries such as Japan, a pronunciation that differs from the superstrate language is created with constant graphics, due to the presence of Japanese characters, which themselves go back to a Chinese origin ( Kanji ). These characters are integrated into the Chinese character system, but spoken according to the Chinese sound. This type of borrowing is sometimes called xingyi 形 譯 / 形 译 (form transference). The peculiarity is that this borrowing took place via the written, i.e. visual, not via the auditory path. Examples:

- 手續 / 手续 shouxu <Japanese. 手 続 き te-tsuzuki (formality)

- 場合 / 场合 changhe <Japanese 場合 baai ( state of affairs , circumstances)

- 服務 / 服务 fuwu <Japanese 服務 fukumu (service)

The Japanese scholars of the early Meiji period in particular admitted that they were inspired by Confucian and Buddhist scriptures from China as well as reference works on classical Chinese literature, and that they were based on Japanese wordings. So certain words between Japan and China were borrowed back and forth in the other direction, especially after the lost Sino-Japanese War (1894/95), so that thorough research is required to determine the exact origin of the word.

Since the Chinese writing consists of morphemes, each fixed syllable in principle has its own meaning. If the phonetic sequence was therefore fixed with Chinese syllables (= morphemes), it may be that the meaning of this sequence cannot be inferred from the translation of the individual morphemes. In order to be able to recognize a loan word as such in the Chinese language, graphemes are often used on the one hand, which otherwise rarely appear in the Chinese script. In this context, there are also phonetic borrowings in Chinese with the formation of new characters. Examples:

- 咖啡 kafei <English coffee

- 檸檬 / 柠檬 ningmeng <English lemon

- 乒乓 pingpang <English ping-pong

New character formation can also be found in the designation of chemical elements. On the other hand, one tries in China to find corresponding graphemes due to the meaning of the morphemes, which are also related to the meaning of the loan word. This is how so-called hybrid formations ( 混合 词 hunheci ) arise , a mixture of sound and meaning transmission (often reduced to two or three syllables), e.g. B.

- 維他命 / 维他命 weitaming (vitamin, lit. "sustaining another's life")

- 可口可樂 / 可口可乐 kekoukele (Coca-Cola, lit. "thirst-quenching and refreshing")

- 啤酒 pi-jiu (beer, lit. "beer-alcohol")

- 芭蕾舞 balei-wu (ballet, lit. "ballet dance")

Purely semantic borrowings are referred to as yiyi 意譯 / 意译 ( meaning transference ) following the classification indicated above . Example:

- 熱狗 / 热狗 regou <English hotdog (lit. "hot dog")

Often sound transmissions and meaning transmissions or hybrids coexist. B. with 因特網 / 因特网 yintewang - wang = "network" and 互聯 網絡 / 互联 网络 hulian wangluo - hulian = to be mutually connected; wangluo = network (both stand for "Internet").

Historical categorization

In the Han dynasty , the influence of borrowings from Central Asia and the northern nomadic tribes was demonstrable, such as

- 獅 / 狮 , shī (lion) <Persian sher / shir

- 葡萄 putao (grapes) < Proto-Iranian bataka, budawa > literary Persian bada, bade (wine)

- 胭脂 yanzhi (blush, red make-up) <? (borrowed from the Xiongnu people )

From the Han to the Tang dynasties , the influence of Buddhism was reflected in a variety of borrowings from Sanskrit . Example:

- 玻璃 boli (glass) <Sanskrit sphatika (rock crystal)

- 蘋果 / 苹果 pingguo (apple) < pinpoluo <sanskrit bimba (ra)

- 佛陀 fotuo (Buddha) <Sanskrit Buddha (the enlightened one)

- 刹那 chana (moment) <Sanskrit ksana

A few Mongolian loanwords have survived from the Yuan dynasty :

- 衚衕 / 胡同 hutong (alley) <Mongolian gudum (fountain)

- 蘑菇 mogu (mushroom) <Mongolian moku

- 俄羅斯 / 俄罗斯 eluosi (Russian) <Mongolian oros

The first Christian missionaries appeared in China at the end of the Ming to the middle Qing dynasties . Terms from Western sciences, Christian terminology and political-diplomatic terms were borrowed from European languages, such as

- 幾何 / 几何 jihe (geometry) < Italian geometria

- 彌撒 / 弥撒 misa (mass) < late Latin missa

- 伯 理 璽 天 德 / 伯 理 玺 天 德 bolixitiande (President) <English president

From the middle of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, the influence of English dominated through the lost Opium Wars , and through the defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894/95 up to the 1930s, the influence of Japanese . Typical examples from this era are:

- 密 司 特 misite <English mister

- 古 的 拜 gudebai <English good-bye

- 苦力 kuli <English coolie / cooly < hindi Kuli ( ethnic group in Gujarat , whose relatives served as foreign workers)

- 德謨 克拉西 / 德谟 克拉西 , démókèlāxī <English democracy

- 德 律 鳳 / 德 律 凤 , délǜfèng <English telephone

- 工業 / 工业 , gōngyè (industry) <Japanese kogyo

- 文化 , wénhuà (culture) <Japanese bunka

The majority of the English and other European borrowings soon went out of fashion again; instead, the written borrowings from Japanese were later used again, such as democracy = 民主 , mínzhǔ , telephone = 電話 / 电话 , dìanhuà .

Some of the borrowings from English into the standard Chinese language took place via Hong Kong , where they arose during the colonial era:

- chocolate (chocolate)> Cantonese 朱古力- Zyugulik > Chinese qiaokeli 巧克力

- tip (tip / hint)> Cantonese 貼士 / 贴士 - tipsi > Chinese tieshi 貼士 / 贴士

Especially when considering the modern Chinese standard language, the influence via the detour of the Chinese regional languages, such as Beijing, Guangzhou (Canton) and Shanghai , for example via television series, must not be neglected. The borrowing of English via the detour of Cantonese is said to be numerous, but only regionally influential. The borrowings via the Shanghai dialect should be more pronounced in the standard language. For example, you can see the dominant influence of the Shanghai dialect when borrowing from the pronunciation of

- 沙發 / 沙发 shafa <Shanghai dialect sa-fa <English sofa , pronunciation actually [sou-fa]

Further examples of borrowing via regional languages:

- 小蜜 xiaomi pretty girl (Beijing dialect)

- 大腕 dawan influential person, v. a. in the entertainment industry (Beijing dialect)

- 減肥 / 减肥 jianfei lose weight, get slim (Guangzhou / Canton)

- 炒魷魚 / 炒鱿鱼 chao youyu jm. to quit, jn. dismissed (Guangzhou / Canton)

- 發燒友 / 发烧友 fashaoyou fan, follower of a hobby (Guangzhou / Canton)

- 搭脈 / 搭脉 damai power to find out sth. About someone (Shanghai)

- 搖 張 / 摇张 yaozhang to earn a lot of money through sth. (Shanghai)

Another special feature are borrowings in which graphemic elements such as Latin letters have found their way into Chinese. For loan words from the English language, acronyms are formed from the first letters of the English word:

- ATM- 機 / ATM- 机 ( ATM-ji ) = ATM

- T- 恤 ( T-xu ) = T-shirt

- X- 光 ( X-Guang ) = X-rays

Transcription systems

Ever since travelers from the west came to China and tried to learn Chinese, there was a need for a phonetic transcription system (romanization system, transcription ) to write down the pronunciation of Chinese characters. Several such systems have emerged since then. The first to find widespread use was the 19th century Wade-Giles system, named after its inventors . This system is still used today, but not in the People's Republic of China. It can be found in old (or English language) textbooks and history books.

In the 20th century, linguists introduced various transcription systems. The most successful of these systems was the Hànyǔ Pīnyīn , which was recognized by the People's Republic of China in 1958 as the official transcription system for the Chinese language. The United Nations and other international organizations later decided to take over Pīnyīn. In the 1950s, when the fight against illiteracy was waged, there were even considerations to abolish the Chinese characters in favor of pīnyīn. However, this was rejected for various reasons, such as the high number of homonyms in Chinese and the fact that the Chinese script is practically the same for all “dialects”, while an alphabet makes the great linguistic differences visible and tangible and possibly a problem for the unity of the state.

A number of different transcription systems are used in Taiwan . The government of the Republic of China decided to use Tongyong Pinyin in 2002 and switched to Hànyǔ Pīnyīn in 2009, but local governments are also allowed to use other transcriptions. In schools, pronunciation is taught with the help of zhùyīn . Efforts to abolish Zhùyīn in favor of Pīnyīn have not progressed very far.

Political discussions

To the displeasure of many Chinese whose mother tongue is not Standard Chinese or the northern dialect, the predominant role of Standard Chinese has led to Standard Chinese being seen as the only Chinese language outside of China. Although both the People's Republic of China and Taiwan have made a standardized Beijing dialect the official language and are campaigning for its nationwide dissemination, there are efforts to preserve the local languages and dialects. Standard Chinese is far from being able to replace it, because the native languages are still used in everyday life, especially in the south of the People's Republic and on Taiwan. Those who only speak standard Chinese are socially disadvantaged in these areas, because many people there speak very poorly or no standard Chinese at all; this is especially true of old people; the younger ones have mostly learned the standard language in school.

In the regions of the People's Republic of China where the majority of Han Chinese live, the coexistence between standard Chinese and the other languages and dialects is generally problem-free. Standard Chinese is promoted as a common working and communication language, at the same time the leadership of the People's Republic of China is careful about the status of the other languages and does not want to restrict their use. Standard Chinese is mainly learned and spoken for practical reasons, as it is often the only way of communication between people from different regions. Sometimes it even happens that two Chinese languages from very close areas are not understandable for the speakers of the other language.

In the Republic of China (Taiwan) , the relationship between standard Chinese and the local languages and dialects, especially Taiwanese, is significantly more complex. Only a minority of Taiwanese speak a northern dialect as their mother tongue, even among the Chinese who fled to Taiwan after the founding of the People's Republic, they mainly speak the Min dialect . There are also a number of native languages and dialects. Until the 1980s, the government tried to restrict the use of Taiwanese and gave it an image of the more primitive. Standard Chinese was promoted in order to uphold the claim to be the rightful successor to the Republic of China founded in 1911. This changed significantly in the 1990s, which is reflected, among other things, in the increased use of Taiwanese in film, radio and television. Extreme proponents of Taiwan's independence oppose Standard Chinese in favor of the Taiwanese language, so the use of Taiwanese is increasingly a question of political leanings. The degree of their use differs from region to region, there is a clear north-south divide with north (Taipei) as standard Chinese and south (Kaohsiung) as Taiwanese stronghold. Efforts to replace Standard Chinese as the official language with Taiwanese or a multilingual standard have so far shown no progress.

Didactics of standard Chinese

In the past ten years, there have been considerable changes in the teaching of Chinese for Chinese as well. The previously common method of teaching how to speak and write Chinese in three successive phases, namely first teaching the characters , then practicing reading, then writing essays, has been reformed by newer approaches, in which primarily speaking in the standard language and performing it in the classroom special oral training in elementary schools is emphasized.

This is mainly justified by the fact that speaking and listening comprehension are most important in everyday life, almost everyone can speak and listen, but not necessarily read and write. In the language courses for Europeans, too, there is a tendency to place greater emphasis on oral skills, starting with listening and imitating simple Chinese sentences and carrying out simple dialogues.

Oral training is supported in the People's Republic of China and in non-Chinese language courses by learning the romanization Hanyu Pinyin . In China, under the slogan Zhuyin shi zi, tiqian du xie ( 注音 识字 , 提前 读写 , in German: "Learn the characters with phonetic transcription and thus learn to read and write earlier"), language teaching in China's primary schools was promoted. The watchword stands for the attempt at reform in the teaching of standard Chinese in elementary schools, which began in 1982 with Heilongjiang at the head. If the children can speak the standard language fluently, then they can fix it quickly and easily with the romanization. The vocabulary is not kept in check by an insufficient amount of learned Chinese characters.

During reading lessons, the Chinese characters are gradually incorporated into the reading and writing process. Only when the linguistic abilities have fully developed are reading large quantities practiced and the conception of essays.

Learning Hanyu Pinyin early on has the further advantage that it is easy to use the Chinese-language input on the computer later.

Chinese as a Foreign Language

Around 40 million people around the world are currently learning (standard) Chinese as a foreign language. China supports learning Chinese with the Confucius Institutes , of which there are a total of 322 in 96 countries and regions (as of Dec. 2010). The number of Chinese learners is increasing rapidly, in 2005 the figure was 30 million. With dong bu dong? ( 懂 不懂? ) The first German-language textbook for standard Chinese, which is designed for secondary school, was published in 2008 .

See also

literature

- Chen, Ping: Modern Chinese. History and Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 0-521-64572-7 .

- Hauser, Françoise: Instructions for use Chinese: This is how the most spoken language in the world works . Reclam, 2015. ISBN 978-3-15-010993-9 .

- Karlgren, Bernhard : Writing and language of the Chinese. 2nd Edition. Springer 2001, ISBN 3-540-42138-6 ( Note: Karlgren's views have been largely refuted today )

- Kneussel, Gregor: Grammar of Modern Chinese. Foreign Language Literature Publishing House, Beijing 2005, ISBN 7-119-04262-9 .

- Lackner, Michael (Ed.): New Terms for new Ideas: western knowledge and lexical change in late imperial China. Brill, Leiden 2001, ISBN 90-04-12046-7 .

- Lee, Wai-Sum; Zee, Eric: Standard Chinese (Beijing). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 33 (1): 109-112. Cambridge University Press 2003, doi : 10.1017 / S0025100303001208 .

- Li, Charles N. and Sandra A. Thompson: Mandarin Chinese. A Functional Reference Grammar. University of California Press, Berkeley 2003, ISBN 0-520-06610-3 .

- Norman, Jerry: Chinese. Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-521-29653-6 .

- Mey, Monika: Chinese. Reading - Understanding - Speaking Wiesbaden, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89500-635-7 .

Web links

General

- Christian Lehmann : Chinese

- Professional Association Chinese eV

- XuexiZhongwen.de (non-commercial site for learning Chinese for Germans)

- Growing up with Chinese , online video course in 100 lessons (English) from Chinese television CCTV

Dictionaries

- DeHanCi : «德 汉 词» Chinese – German, German – Chinese dictionary of words and sentences

- HanDeDict 漢 德 詞典 Chinese-German, German-Chinese dictionary (project discontinued - database transferred to HanDeDict @ Zydeo and continued)

- HanDeDict @ Zydeo 汉 德 词典 Chinese-German, German-Chinese dictionary with handwritten input of characters

- Leo dictionary Chinese-German, German-Chinese

- Index-based Chinese-German dictionary (with stroke order and example sentences)

- Zhongwen.com (Chinese-English)

- Tasty Mantou Chinese (Chinese – German, German – Chinese)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bingwen Liu, Lei Xiong (ed.): 100 under 1 billion: Conversations with the Chinese about everyday life, hopes and fears . From the Chinese by Liangjion Li and Renate Zantis, Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen, 1989, DOI: 10.1007 / 978-3-322-91586-3_89 .

- ↑ Lin Liu, Hwei Ann: The division of China and its linguistic consequences . In: Living Languages . Volume 40, No. 1, 2009, pp. 5-8, DOI: 10.1515 / les.1995.40.1.5 .

- ↑ In the original: 「以 北京 语音 为 标准音 , 以 北方 话 为 基础 方言 , 以 典型 的 现代 白话文 著作 为 语法 规范」 . Conference on the Standardization of Modern Chinese, 1956. Quoted in Ping Chen: Modern Chinese. History and Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ Jerry Norman: Chinese. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988, p. 251.

- ↑ Sihua Liang: Language Attitudes and Identities in Multilingual China. A Linguistic Ethnography. Springer, Cham u. a. 2015, p. 45.

- ↑ Chris Luo: One-third of Chinese do not speak Putonghua, says Education Ministry. In: South China Morning Post (online), September 22, 2014.

- ↑ [1] . Evaluated on January 12, 2006

- ↑ [2] . Evaluated on January 12, 2006.

- ↑ [3] . Evaluated on January 12, 2006.

- ↑ 清 薛福成 «出使 四 国 日记 · 光绪 十六 年 十二月 二十 九日»: “美洲 各国 及 欧洲 之 瑞士 与 法国 皆 民主 之 国 国 也 , 其 政权 全 在 议院 , 而 伯 理 璽 天 德(译作 总统) 无权 焉. ”亦 省 作“ 伯 理 ”.

- ↑ According to china.org.cn of December 14, 2010, accessed May 25, 2011

- ↑ According to China Radio International , accessed May 25, 2011.