Robert Havemann

Robert Hans Günther Havemann (born March 11, 1910 in Munich ; † April 9, 1982 in Grünheide ) was a German chemist , communist , resistance fighter against National Socialism ( Red Orchestra and resistance group European Union ) and critic of the regime in the GDR .

life and work

Family and education

Robert Havemann was the son of the painter Elisabeth Havemann (born of Schönfeldt) and the teacher, editor and writer Hans Havemann (1887-1985), among other things, the Dadaist piece of Judgment: The tragedy of the primal sounds AEIOU under the pseudonym Jan van Mehan published . In 1929 Robert Havemann began studying chemistry in Munich, moved to Berlin in 1931 and graduated there in 1933. On October 16, 1935, he received his doctorate from the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin .

In 1934 Robert Havemann and Antje Hasenclever married . The marriage ended in divorce in 1947. Two years later, Havemann and Karin von Trotha, née von Bamberg (* 1916), married. This marriage ended in divorce in 1966; her descendants are Frank Havemann (* 1949), Florian Havemann (* 1952) and Sibylle Havemann (* 1955, she has two children together with Wolf Biermann ). From 1962 to 1971 he was in a relationship with Brigitte Martin . He is the father of her two daughters.

Robert Havemann and Annedore (Katja) Grafe married on April 26, 1974 .

Nazi dictatorship

In 1933 he began a dissertation with the colloid researcher Herbert Freundlich on "Ideal and real protein solutions" at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry. Even before the National Socialists came to power , he joined the later resistance group Neu Beginnen . Freundlich emigrated at the end of July 1933 and Havemann, like all other remaining employees, had to leave the institute after restructuring. Before that, in the summer of 1933, he denounced Freundlich's plan to have Fritz Haber and Max Planck send some of the devices that had been purchased from the Rockefeller Foundation to the KWIpCh in exile in London. This delayed the project. Thanks to a DFG scholarship, he received his doctorate in Berlin in 1935 on the basis of a successfully defended physico-chemical dissertation .

He then worked for six years, from 1937 to 1943, on a scientific paper on a poison gas project for the Army Weapons Office and completed his habilitation in March 1943.

In 1943 Havemann initiated the " European Union " resistance group . Through his nephew Wolfgang Havemann , he was also in regular contact with Arvid Harnack and others from the Berlin Red Orchestra. After the Gestapo had received information about his conspiratorial activity, he was arrested on September 5, 1943 in Berlin and initially imprisoned in the Gestapo prison at Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 8 and later in the Brandenburg-Görden prison, where he did his research in one a laboratory specially prepared for him. On December 16, 1943 he was sentenced to death by the People's Court under Roland Freisler for high treason . Through the advocacy of several authorities, in particular Professor Wolfgang Wirth , Senior Physician at the Army Weapons Office, Havemann was able to postpone the execution of the sentence several times until the end of the war. It was argued that Havemann was needed for "war-important" research. During the war he was supplied from the United States by Gerhard Bry (1911-1996) with scientific publications and food shipments. The Red Army liberated him on April 27, 1945 .

Life between 1945 and 1965

In 1945 he was made head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, today's Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society , in Berlin-Dahlem and the head of all the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes that remained in Berlin. From this position he developed a plan to rescue the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes that remained in Berlin, which the educational reformer Fritz Karsen took up and developed the plan for a German research university based on .

On April 10, 1947, Havemann testified as a witness for the prosecution in the Nuremberg legal process against Ernst Lautz .

In the autumn of 1947, responsibility for the Dahlem Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was transferred from the Allied Command and / or the overall Berlin city administration to the American city commandant. In January 1948 Havemann was dismissed as head of the Berlin Kaiser Wilhelm Society (the umbrella association of the institutes). "The American military government justified this step with the fact that it had only inadequately complied with the 'Act on the Regulation and Monitoring of Scientific Research' (Act No. 25) issued by the Allied Control Council." His position as head of the department for colloid chemistry and biomedicine at the Kaiser -Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry he was allowed to keep until he left the company in 1950.

In January 1950, Robert Havemann was banned from his profession and house because of his agitation against the hydrogen bomb in the USA , which the city councilor Walter May (SPD) responsible for public education justified as follows:

"I have regretted that you have chosen New Germany as your publication organ (see from 5.2.50), i. H. the Berlin daily newspaper that systematically throws dirt at the liberal population of Berlin and their corporations. The introduction to your essay in particular shows a striking adaptation to the terminology used in New Germany. I can only see one affront you consciously brought about, with which you destroy the trust that I consider to be indispensable as a prerequisite for your activity at a Dahlem institute. "

In the same year he was appointed director of the Institute for Physical Chemistry at the Humboldt University in East Berlin and professor for physical chemistry. In 1951 he joined the SED . On this occasion, a retrospective declaration of Havemann's party membership in the KPD since 1932.

From 1946 to 1963 Havemann worked with the KGB , the Ministry for State Security and the Army Reconnaissance of the GDR. As a “secret informator” (GI, code name “Leitz”), he provided the State Security with more than 140 individual pieces of information at 62 meetings with his commanding officer - including incriminating personal information at 19 meetings. This emerges from a study by the federal authority for the records of the State Security Service of the former GDR published in 2005 , which for the first time examines in detail the content and intensity of Havemann's unofficial Stasi collaboration, which has been publicly known since the 1990s. Havemann was therefore given the task of reporting on the mood in the East German scientific community and was targeted specifically at West German scientists. In his reports he charged GDR scientists, among others, with statements about their possible intention to flee the GDR.

He was a member of the Scientific Council for the Peaceful Use of Atomic Energy . He was a member of the People's Chamber of the GDR until 1963 and was awarded the GDR National Prize in 1959 . Since 1950 he was a member of the German Peace Committee (later the Peace Council of the GDR ) and visited Albert Schweitzer in Gabon in January 1960 with Gerald Götting .

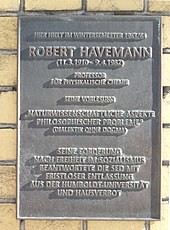

Exclusion from the SED in 1964

In the winter semester of 1963/64 Havemann held a series of lectures at the Humboldt University on the subject of scientific aspects of philosophical problems (published in the Federal Republic under the title: Dialectics without Dogma? ). A critical newspaper interview with him appeared in the Federal Republic of Germany. As a result, on March 12, 1964, an extraordinary general meeting of the SED party organization was called at the Humboldt University in East Berlin . The latter decided to expel Havemann from the party because he had deviated from the line of Marxism-Leninism “under the flag of the struggle against dogmatism ” and had “been guilty of betrayal of the cause of the workers and peasants”.

The State Secretariat for Higher Education and Technical Education in the GDR decided on March 12, 1964 to withdraw Havemann's teaching post, giving the following reasons on March 13, 1964, among other things:

“By publicly slandering our workers 'and peasants' power in interviews with Western press representatives and considering it not beneath his dignity to use the publication organs in West Germany and thus support the anti-GDR plans of the militarists and revanchists, he has the The obligation assumed by his appointment and the legally stipulated obligations of a university professor in the GDR grossly violated. "

At the beginning of February 1964 the SED had already raised sharp accusations against Havemann in connection with Havemann's philosophical lecture series on the subject of general freedom, freedom of information and dogmatism . On March 6, 1964, Havemann had a conversation with the Hamburg lawyer Karl-Heinz Neß (Ness) about these allegations and his intentions in the lecture series, which he allegedly sold as an interview to the newspaper Hamburger Echo without authorization. The conversation note was published on March 11, 1964 and subsequently denied by Havemann.

Professional ban and house arrest

On March 12, 1964, the London Times reported that Havemann had said in an interview to a Hamburg evening newspaper that what intellectual freedom is possible in other socialist countries must also be possible in East Germany. His lectures at Humboldt University served the purpose of openly criticizing “the excesses of the Stalin era”. Havemann was banned from practicing his profession in 1965 and was expelled from the GDR Academy of Sciences on April 1, 1966 . In the following years he published numerous SED-critical publications in the West German media in the form of newspaper articles and books (including questions, answers, questions ; Robert Havemann: Ein deutscher Kommunist ; Morgen ).

In 1976 he protested against the expatriation of his friend, the dissident songwriter Wolf Biermann , from the GDR. Havemann did this in the form of an appeal to the chairman of the State Council, Erich Honecker , which he published on November 22, 1976 in the West German news magazine Der Spiegel .

Because of the collection of news (§ 98 StGB-GDR ) on the basis of Havemann's contacts to West German media, the Fürstenwalde district court imposed a sentence on November 26, 1976 for "activities [...] that. Because he was incapable of imprisonment due to his tuberculosis illness threaten public safety and order ”, an unlimited residence restriction , which corresponded to house arrest on his property in Burgwallstraße in Grünheide. His house and his family (and also the family of his friend Jürgen Fuchs , whom he took into his garden house in 1975) were monitored around the clock by the Stasi . House arrest was lifted after three years, but surveillance continued. The State Security also drew up a list of over 70 GDR citizens who were refused entry to Havemann's house. Havemann was also prohibited from contacting diplomats and journalists.

In 1979, criminal proceedings for “foreign exchange offenses ” were opened. This served mainly to suppress Havemann's publications in the Federal Republic of Germany. In 1982 he joined the pastor Rainer Eppelmann in the “ Berlin Appeal ” for an independent all-German peace movement . Havemann died shortly afterwards. At his funeral in the Grünheider cemetery, Am Schlangenluch, around 250 mourners were found, who were also photographed by the state security as part of the permanent surveillance. On November 28, 1989, the Central Party Control Commission (ZPKK) of the SED carried out his posthumous rehabilitation. In 2000, two former East German public prosecutors were sentenced to prison terms because of house arrest for perverting the law .

Honors

- On May 6, 1955 Havemann received the Patriotic Order of Merit in silver.

- In 1959 he received the GDR's National Prize, Second Class, one of the highest honors for scientists.

- In 2005 he was posthumously awarded the title Righteous Among the Nations at the Yad Vashem Memorial because of his membership in the "European Union" resistance group. The Union had hidden Jews to save them from deportation, and from 1942 onwards it also supported foreign forced laborers .

- A memorial plaque was placed on the building of the former Institute for Chemistry at Berlin's Humboldt University in Berlin-Mitte , informing about Havemann's teaching activities at this location.

- On January 31, 1992, Erich-Glückauf-Strasse in Berlin-Marzahn was renamed Havemannstrasse.

- In March 1991 in Gera in the Bieblach -Ost development area, Dr.- Hans-Loch -Strasse was renamed Robert-Havemann-Strasse.

- Robert Havemann has been an honorary citizen of Grünheide (Mark) since 1999 . He is buried in the forest cemetery in Grünheide (Mark).

- In the House of Democracy and Human Rights in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg , the largest conference room is named after Robert Havemann.

The Robert-Havemann Gymnasium in Berlin-Karow was named after him.

See also

- History of the German Democratic Republic

- Opposition and Resistance in the GDR

- Robert Havemann Society

- Rudolf Bahro

Works (selection)

- 1951: Nuclear technology secret? Ed. By Dt. Peace Committee and the Chamber of Technology. Verlag Technik, Berlin 1951, 31 p., Ill ., DNB 573694060

- 1957: Introduction to chemical thermodynamics. Edited by Franz X. Eder and Robert Rompe . German Verlag der Wiss. , Berlin 1957, 296 pp., 95 illustrations, DNB 451876849

- 1964: dialectics without dogma? Science and worldview. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1964. Extended edition 1990, ed. by Dieter Hoffmann and with an essay by Hartmut Hecht. German Verlag der Wissen., Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-326-00628-4 .

- 1970: questions, answers, questions. From the biography of a German Marxist. Piper, 1970, ISBN 3-492-01860-2 . rororo 1972, ISBN 3-499-11556-5 . Structure 1990, ISBN 3-351-01775-8 .

- 1971: Responses to the head office ›Eternal Truths‹. Edited by Hartmut Jäckel . Piper 1971. Extended: 287 p., Dt. Verlag der Wissen., 1990, ISBN 3-326-00657-8 .

- 1976: Berlin writings. Essays, interviews, conversations and letters from 1969 to 1976. Edited by Andreas W. Mytze. european ideas, Berlin 1976.

- 1976: About censorship and the media. DeutschlandArchiv 1976, pp. 798-800.

- 1978: a German communist. Retrospectives and perspectives from isolation. Edited by Manfred Wilke. Reinbek, Rowohlt 1978.

- 1980: tomorrow. The industrial society at a crossroads. Criticism and Real Utopia. Piper-Verlag 1980, ISBN 3-492-02617-6 . Copenhagen 1981, DNB 368960064 . Stockholm 1981, DNB 368960072 . Fischer-TB 1982, ISBN 3-596-23472-7 . Mitteldeutscher Verlag 1990, ISBN 3-354-00702-8 . Edition Zeitsprung 2010, ISBN 978-3-8391-3657-7 .

- 1990: The voice of conscience. Texts by a German anti-Stalinist. Edited by Rüdiger Rosenthal. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990, 224 pages, ISBN 3-499-12813-6 .

- 1990: Why I was a Stalinist and became an anti-Stalinist. Texts of an inconvenient. Edited by Dieter Hoffmann and Hubert Laitko . Dietz, Berlin 1990, ISBN 978-3-320-01614-2 .

- 2007: Werner Theuer: Robert Havemann Bibliography. On behalf of the Robert Havemann Society. Edited and appended by Bernd Florath. Akademie, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-05-004183-8 , ISBN 978-3-05-004183-4 (A selection of secondary literature on H. is also listed for the years from 1945 onwards. The appendix contains previously unpublished texts and documents from the direct post-war period to the conception of Germany R.Hs.)

literature

- Hartmut Jäckel (ed.): A Marxist in the GDR. For Robert Havemann. Piper, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-492-02539-0 .

- Silvia Müller and Bernd Florath (eds.): The discharge: Robert Havemann and the Academy of Sciences 1965/66. A documentation. Series of the Robert Havemann Archive, Volume 1, Berlin 1996.

- Clemens Vollnhals : The Havemann case. A lesson in political justice . .Links, Berlin 1998

- Manfred Wilke , Werner Theuer: The proof of treason cannot be produced. Robert Havemann and the European Union resistance group. In: Germany Archive , Cologne, 32nd year, 1999, no. 6, pp. 899–912.

- Simone Hannemann: Robert Havemann and the "European Union" resistance group. A presentation of the events and their interpretation after 1945. Series of publications by the Robert Havemann Society, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-9804920-5-2 .

- Christof Geisel, Christian Sachse: Rediscovery of a non-person. Robert Havemann in autumn 1989 - Two studies. Berlin 2000.

- Friedrich Christian Delius : My year as a murderer . Rowohlt • Berlin, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-87134-458-3 .

- Arno Polzin: Robert Havemann's change from unofficial employee to dissident as reflected in the MfS files . BStU Berlin, BF informs, issue 26, 2005, PDF .

- Christian Sachse: The political explosive power of physics. Robert Havemann in the triangle between science, philosophy and socialism (1956–1962). Lit Verlag, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-8979-3 .

- Hubert Laitko : chemist - philosopher - dissident. In: News from chemistry. 58, 2010, pp. 655-658, doi: 10.1002 / nadc.201071446 .

- Konrad Fuchs : Havemann, Robert. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 25, Bautz, Nordhausen 2005, ISBN 3-88309-332-7 , Sp. 535-544.

- Andreas Heyer: Ecology and Opposition - The political utopias of Wolfgang Harich and Robert Havemann . Philosophical Conversations Volume 14. Helle Panke. Berlin, 2009.

- Dieter Hoffmann : Havemann, Robert . In: Who was who in the GDR? 5th edition. Volume 1. Ch. Links, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86153-561-4 .

- Karl-Heinz Bernhardt , Hannelore Bernhardt : Robert Havemann (1910-1982) and the German Academy of Sciences. Meeting reports of the Leibniz Society of Sciences in Berlin , Volume 109, pp. 157-160. Trafo Wissenschaftsverlag Dr. Wolfgang Weist, Berlin 2011.

- Alexander Amberger: Bahro, Harich, Havemann. Marxist criticism of the system and political utopia in the GDR. Verlag F. Schöningh, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 3-506-77982-6 .

- Ines Weber: Socialism in the GDR. Alternative social concepts by Robert Havemann and Rudolf Bahro. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-86153-861-5 .

- Bernd Florath (Ed.): Approaches to Robert Havemann. Biographical studies and documents. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-525-35117-8 .

family

- Florian Havemann : Havemann. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 2007, 1092 pp., ISBN 978-3-518-41917-5 , review:

- Katja Havemann and Joachim Widmann : Robert Havemann or How the GDR did away with itself. Ullstein, Berlin 2003, ISBN 978-3-550-07570-4 .

Documents

- Dieter Hoffmann (Hrsg.): Robert Havemann: Documents of a life . Links, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-86153-022-8

- Werner Theuer, Bernd Florath: Robert Havemann Bibliography . With unpublished texts from the estate. Edited by the Robert Havemann Society. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-05-004183-4

- Werner Theuer, Arno Polzin: Havemann files landscape: Estate and archive holdings on Robert Havemann in the Robert Havemann Society and at the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic . Edited by the Robert Havemann Society and the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records. Berlin, 2008, ISBN 978-3-938857-07-6

Movie

- Thinking about Robert Havemann. (Alternative title: Naja, der Robert. ) Documentation, BR Germany, 1991, 45 min., Script and direction: Hans-Dieter Rutsch, production: DEFA -Studio for Documentary Films, DFF , WDR , first broadcast: February 3, 1991 in the DFF. With interviews by Katja Havemann, Wolf Biermann , Horst Nieswandt, Hartmut Jäckel , Jürgen Fuchs , Brigitte Haeseler, Bärbel Bohley , Robert Jungk and others. a.

- Contradiction - Havemann and Communism. Documentation, BR Germany, 2014, 45 min., Script and direction: Ute Bönnen and Gerald Endres, production: Ute Bönnen - Gerald Endres film production, first broadcast: October 21, 2014 on RBB .

Web links

- Literature by and about Robert Havemann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Robert Havemann in the German Digital Library

- Havemann's biography at the Robert Havemann Society

- Regina Haunhorst, Irmgard Zündorf: Robert Havemann. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG ), last updated on January 22, 2016

- Short biography of the German Resistance Memorial Center

- Robert Havemann in the Munzinger archive ( beginning of article freely available)

- Life data, publications and academic family tree of Robert Havemann at academictree.org, accessed on April 22, 2018.

- Robert Havemann at Theoretical Chemistry Genealogy Project

- The Havemann estate and archive holdings on Robert Havemann at the BStU

- Robert Havemann in the Biographical Lexicon Resistance and Opposition in Communism 1945–91 of the Federal Foundation for Coming to terms with the SED dictatorship

- BStU , topic: Robert Havemann: From IM to Public Enemy

Individual evidence

- ↑ 1921; New edition: Verlag Peter Ludewig, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-9810572-5-6 .

- ↑ Dieter Hoffmann (Ed.): Robert Havemann: Documents of a life . Links, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-86153-022-8 , page 23.

- ↑ biographical data, publications and Academic pedigree of Robert Havemann in academictree.org, accessed on February 8 2018th

- ↑ Georg Diez : "We are a damaged family" Robert Havemann's children fight over their dead father. A visit to Sibylle Havemann . In: Die Zeit , No. 4/2008.

- ↑ see footnote 29 in: Was Robert Havemann an anti-Semite? Federal Agency for Civic Education , July 25, 2012; Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ An often rumored assumption. By contrast, Reinhard Rürup : fates and careers. Memorial book for the […] displaced researchers. Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89244-797-9 , p. 98: “However, there is no evidence for a politically motivated expulsion of doctoral student Havemann from the institute. Rather, it is documented that in the summer of 1933 Havemann informed the former managing director of the NSDAP parliamentary group, who had meanwhile become the personal assistant to the Reich Minister of the Interior, that some of the [sc. expelled] researchers […] intended to relocate the apparatus and instruments that the Rockefeller Foundation […] had made available to them to their new workplaces. ”These relocations were stopped and a“ rigorous investigation ”followed. Rürup reflects the common assumption that this denunciation was committed out of “political disorientation and confusion” and is thus glossed over. But there is no evidence that Havemann was in any way oppositional. In autumn 1933, H. and Georg Groscurth were dismissed by Gerhard Jander .

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze : Fritz Haber. 1st edition 1998, p. 670ff. ISBN 3-406-43548-3 .

- ↑ Gert Rosiejka: The Red Chapel. 2nd, ex. Edition 1990.

- ^ Robert Havemann: A German Communist. Review and perspectives from isolation . Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek 1978, ISBN 3-498-02846-4 , p. 56-59 .

- ^ Robert Havemann: Questions, Answers, Questions. From the biography of a German Marxist . R. Piper & Co. Verlag, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-492-11324-9 , pp. 83 .

- ^ Robert Havemann: Documents of a life . Edited by Dirk Draheim. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 1991. ISBN 978-3-86153-022-0 , pp. 58-59, 70-73.

- ^ Inga Meiser: The German Research University (1947–1953) . Publications from the archive of the Max Planck Society, Volume 23, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-927579-27-9 . The study is the revised version of a dissertation submitted in 2010; it is available online at Inga Meiser: Die Deutsche Forschungshochschule (PDF) p. 79

- ↑ Dirk Draheim u. a. (Ed.): Robert Havemann. Documents of a life. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 1991, p. 106, Document 2-9.

- ^ Robert Havemann (March 11, 1910 to April 9, 1982.) ( Memento of November 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Bundesarchiv

- ↑ Arno Polzin: Robert Havemann's change from unofficial employee to dissident as reflected in the MfS files . BStU Berlin, BF informs, issue 26, 2005.

- ↑ For IM activities see also: Nordkurier January 4, 2006.

- ↑ Like Socrates . In: Der Spiegel . No. 12 , 1964 ( online ).

- ↑ The Times notes in the short article at the end that another GDR academic, “Professor Mothes from Halle”, had recently made similar public statements.

- ↑ Biermann must remain a citizen of the GDR . In: Der Spiegel . No. 48 , 1976 ( online ).

- ^ Robert Havemann 1976. jugendopposition.de; Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ↑ Joachim Widmann: House arrest should isolate the regime critic. How the GDR tried to silence Havemann . In: Berliner Zeitung , October 1, 1997

- ^ Prison sentences for ex-GDR public prosecutors , dpa / Rheinische Post , August 15, 2000.

- ↑ Robert Havemann on the website of Yad Vashem (English)

- ↑ Havemannstrasse. In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert )

- ^ From March (1991) new street names. Stadt-Anzeiger Gera, 1991, accessed October 26, 2013 .

- ^ House of Democracy and Human Rights - Event Rooms , accessed on October 1, 2018.

- ↑ Havemann 1980 (morning) - meeting at Umweltdebatte.de

- ↑ Wolfgang Templin : A look into the cupboards. In: Tagesspiegel , December 3, 2007

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Havemann, Robert |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Havemann, Robert Hans Günther; Havemann, Robert H. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German chemist, politician (SED), MdV and regime critic in the GDR |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 11, 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 9, 1982 |

| Place of death | Grünheide |