User talk:Tohd8BohaithuGh1/Archive 1 and Ming dynasty: Difference between pages

m stop sign |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses|Ming}} |

|||

{{message|User:Tohd8BohaithuGh1}} |

|||

{{Infobox Former Country |

|||

<!-- Template from Template:Welcomeg --> |

|||

|native_name = 大明 |

|||

{| style="background-color:#F5FFFA; padding:0;" cellpadding="0" |

|||

|conventional_long_name = Great Ming |

|||

|style="border:1px solid #084080; background-color:#F5FFFA; vertical-align:top; color:#000000;"| |

|||

|common_name = Ming Dynasty |

|||

{| width="100%" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="5" style="vertical-align:top; background-color:#F5FFFA; padding:0;" |

|||

| |

|||

| <div style="margin:0; background-color:#CEF2E0; font-family:sans-serif; border:1px solid #084080; text-align:left; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top:0.2em; padding-bottom:0.2em;">Hello, {{BASEPAGENAME}}! [[Wikipedia:Welcoming committee/Welcome to Wikipedia|Welcome]] to Wikipedia! Thank you for [[Special:Contributions/{{BASEPAGENAME}}|your contributions]] to this free encyclopedia. If you decide that you need help, check out ''Getting Help'' below, ask me on {{#if: |[[User talk:{{{1}}}|my talk page]]|my talk page}}, or place '''{{tl|helpme}}''' on your talk page and ask your question there. Please remember to [[Wikipedia:Signatures|sign your name]] on talk pages by clicking [[Image:Signature icon.png]] or using four tildes (<nowiki>~~~~</nowiki>); this will automatically produce your username and the date. Finally, please do your best to always fill in the [[Help:Edit summary|edit summary]] field. Below are some useful links to facilitate your involvement. Happy editing! - <font face="Verdana">[[User:Cobaltbluetony|CobaltBlueTony™]] <sub>[[User_talk:Cobaltbluetony#top|talk]]</sub></font> 20:06, 30 June 2008 (UTC) |

|||

|continent = Asia |

|||

|} |

|||

|region = China |

|||

{| width="100%" style="background-color:#F5FFFA;" |

|||

|country = China |

|||

|style="width: 55%; border:1px solid #FFFFFF; background-color:#F5FFFA; vertical-align:top"| |

|||

|era = |

|||

{| width="100%" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="5" style="vertical-align:top; background-color:#F5FFFA" |

|||

|status = Empire |

|||

! <div style="margin: 0; background-color:#084080; font-family: sans-serif; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #CEF2E0; text-align:left; color:#FFC000; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top: 0.2em; padding-bottom: 0.2em;">Getting started</div> |

|||

|status_text = |

|||

|- |

|||

|empire = |

|||

|style="color:#000"| |

|||

|government_type = Monarchy |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Tutorial|A tutorial]] • [[Wikipedia:Five pillars|Our five pillars]] • [[Wikipedia:Adopt-a-User|Getting mentored]] |

|||

| |

|||

* How to: [[Wikipedia:How to edit a page|edit a page]] • [[Wikipedia:Images|upload and use images]] |

|||

|year_start = 1368 |

|||

|- |

|||

|year_end = 1644 |

|||

! <div style="margin: 0; background:#084080; font-family: sans-serif; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #CEF2E0; text-align:left; color:#FFC000; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top: 0.2em; padding-bottom: 0.2em;">Getting help</div> |

|||

| |

| |

||

|year_exile_start = 1644 |

|||

| style="color:#000"| |

|||

|year_exile_end = 1662 |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:FAQ|Frequently asked questions]] • [[Wikipedia:Tips|Tips]] |

|||

| |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Questions|Where to ask questions or make comments]] |

|||

|event_start = Established in [[Nanjing]] |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Requests for administrator attention|Request administrator attention]] |

|||

|date_start = [[January 23]] [[1368]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|event_end = Fall of [[Beijing]] |

|||

! <div style="margin: 0; background:#084080; font-family: sans-serif; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #CEF2E0; text-align:left; color:#FFC000; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top: 0.2em; padding-bottom: 0.2em;">Policies and guidelines</div> |

|||

|date_end = [[June 6]] [[1644]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

| style="color:#000"| |

|||

|event1 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Neutral point of view|Neutral point of view]] • [[Wikipedia:No original research|No original research]] |

|||

|date_event1 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Verifiability|Verifiability]] • [[Wikipedia:Reliable sources|Reliable sources]] • [[Wikipedia:Citing sources|Citing sources]] |

|||

|event2 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:What Wikipedia is not|What Wikipedia is not]] • [[Wikipedia:Biographies of living persons|Biographies of living persons]] |

|||

|date_event2 = |

|||

<hr /> |

|||

|event3 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Manual of Style|Manual of Style]] • [[Wikipedia:Three-revert rule|Three-revert rule]] • [[Wikipedia:Sock puppetry|Sock puppetry]] |

|||

|date_event3 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Copyrights|Copyrights]] • [[Wikipedia:Non-free content|Policy for non-free content]] • [[Wikipedia:Image use policy|Image use policy]] |

|||

|event4 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:External links|External links]] • [[Wikipedia:Spam|Spam]] • [[Wikipedia:Vandalism|Vandalism]] |

|||

|date_event4 = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Deletion policy|Deletion policy]] • [[Wikipedia:Conflict of interest|Conflict of interest]] • [[Wikipedia:Notability|Notability]] |

|||

| |

| |

||

|event_post = End of the Southern Ming |

|||

|} |

|||

|date_post = April, 1662 |

|||

|class="MainPageBG" style="width: 55%; border:1px solid #FFFFFF; background-color:#F5FFFA; vertical-align:top"| |

|||

| |

|||

{| width="100%" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="5" style="vertical-align:top; background-color:#F5FFFA" |

|||

|p1 = Yuan Dynasty |

|||

! <div style="margin: 0; background-color:#084080; font-family: sans-serif; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #CEF2E0; text-align:left; color:#FFC000; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top: 0.2em; padding-bottom: 0.2em;">The community</div> |

|||

|s1 = Shun Dynasty |

|||

|- |

|||

|s2 = Qing Dynasty |

|||

|style="color:#000"| |

|||

|flag_s2 = China Qing Dynasty Flag 1889.svg |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Consensus|Build consensus]] • [[Wikipedia:Dispute resolution|Resolve disputes]] |

|||

| |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Assume good faith|Assume good faith]] • [[Wikipedia:Civility|Civility]] • [[Wikipedia:Etiquette|Etiquette]] |

|||

|image_flag = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:No personal attacks|No personal attacks]] • [[Wikipedia:No legal threats|No legal threats]] |

|||

|flag = |

|||

<hr /> |

|||

|flag_type = |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Community Portal|Community Portal]] • [[Wikipedia:Village pump|Village pump]] |

|||

| |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Wikipedia Signpost|Signpost]] • [[Wikipedia:IRC channels|IRC channels]] • [[Wikipedia:Mailing lists|Mailing lists]] |

|||

|image_coat = |

|||

|- |

|||

|symbol = |

|||

! <div style="margin: 0; background-color:#084080; font-family: sans-serif; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #CEF2E0; text-align:left; color:#FFC000; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top: 0.2em; padding-bottom: 0.2em;">Writing articles</div> |

|||

|symbol_type = |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

|style="color:#000"| |

|||

| |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Be bold|Be bold in editing]] • [[Wikipedia:Article development|Develop an article]] |

|||

|image_map = Ming-Empire2.jpg |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:The perfect article|The perfect article]] • [[Wikipedia:Manual of Style|Manual of style]] |

|||

|image_map_caption = Ming China under the [[Yongle Emperor]] |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Stub|Stubs]] • [[Wikipedia:Categorization|Categories]] • [[Wikipedia:Disambiguation|Disambiguation]] |

|||

| |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Pages needing attention|Pages needing attention]] • [[Wikipedia:Peer review|Peer review]] |

|||

|capital = [[Nanjing]]<br><small>(1368-1421)</small><br>[[Beijing]]<br><small>(1421-1644) |

|||

|- |

|||

<!-- |These were the capitals exile of Southern Ming: capital_exile = [[Nanjing]] <small>(1644)</small>, [[Fuzhou]] <small>(1645-1646)</small>, [[Guangzhou]] <small>(1646-1647),</small> [[Zhaoqing]] <small>(1446-1652)</small>etc. --> |

|||

! <div style="margin: 0; background-color:#084080; font-family: sans-serif; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #CEF2E0; text-align:left; color:#FFC000; padding-left:0.4em; padding-top: 0.2em; padding-bottom: 0.2em;">Miscellaneous</div> |

|||

|latd=39|latm=54|latNS=N|longd=116|longm=23|longEW=E |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

|style="color:#000"| |

|||

|common_languages = [[Chinese language|Chinese]] |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Username policy|User name]] • [[Wikipedia:User page|User pages]] • [[Wikipedia:Talk page|Talk pages]] |

|||

|religion = [[Buddhism]], [[Taoism]], [[Confucianism]], [[Chinese folk religion]] |

|||

* Clean up: [[Wikipedia:Cleanup|General]] - [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Spam|Spam]] - [[Wikipedia:Cleaning up vandalism|Vandalism]] |

|||

|currency = [[Chinese cash]], [[Chinese coin]], [[Banknote|Paper currency]] (later abolished) |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:WikiProject|Join a WikiProject]] • [[Wikipedia:Translation|Translation]] |

|||

| |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:Template messages|Useful templates]] • [[Wikipedia:Tools|Tools]] • [[Wikipedia:WikiProject User scripts|User scripts]] |

|||

|leader1 = [[Hongwu Emperor]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|leader2 = [[Chongzhen Emperor]] |

|||

|} |

|||

|year_leader1 = 1368-1398 |

|||

|} |

|||

|year_leader2 = 1627-1644 |

|||

|}<!--Template:Welcomeg--> |

|||

|title_leader = [[List of Emperors of the Ming Dynasty|Emperor]] |

|||

|deputy1 = [[Liu Ji]] |

|||

|deputy2 = [[Yan Song (Ming Dynasty)|Yan Song]] |

|||

|deputy3 = [[Tan Lun]] |

|||

|deputy4 = [[Zhang Juzheng]] |

|||

|deputy5 = [[Zhu Guozhen (Ming Dynasty)|Zhu Guozhen]] |

|||

|year_deputy1 = 1368–1398 |

|||

|year_deputy2 = – |

|||

|year_deputy3 = |

|||

|year_deputy4 = – |

|||

|year_deputy5 = |

|||

|title_deputy = [[Chancellor of China|Chancellor]] |

|||

| |

|||

|stat_year1 = 1393 |

|||

|stat_area1 = |

|||

|stat_pop1 = 72,700,000 |

|||

|stat_year2 = 1400 |

|||

|stat_area2 = |

|||

|stat_pop2 = 65,000,000¹ |

|||

|stat_year3 = 1600 |

|||

|stat_area3 = |

|||

|stat_pop3 = 150,000,000¹ |

|||

|stat_year4 = 1644 |

|||

|stat_area4 = |

|||

|stat_pop4 = 100,000,000 |

|||

|stat_year5 = |

|||

|stat_area5 = |

|||

|stat_pop5 = |

|||

|footnotes = Remnants of the Ming Dynasty ruled southern China until 1662, a dynastic period which is known as the Southern Ming.<br />¹ The numbers are based on estimates made by C.J. Peers in ''Late Imperial Chinese Armies: 1520-1840'' |

|||

}} |

|||

{{History of China}} |

|||

The '''Ming Dynasty''' ({{zh-cp|c=明朝|p=Míng Cháo}}), or '''Empire of the Great Ming''' ({{zh-tsp|t=大明國|s=大明国|p=Dà Míng Guó}}), was the ruling [[Dynasties in Chinese history|dynasty]] of [[China]] from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the [[Mongol]]-led [[Yuan Dynasty]]. The Ming was the last dynasty in China ruled by ethnic [[Han Chinese|Han]]s (the main Chinese ethnic group), before falling to the rebellion led in part by [[Li Zicheng]] (李自成) and soon after replaced by the [[Manchu]]-led [[Qing Dynasty]]. Although the Ming capital [[Beijing]] fell in 1644, remnants of the Ming throne and power (collectively called the '''Southern Ming''') survived until 1662. |

|||

Ming rule saw the construction of a vast [[Naval history of China|navy]] and a [[standing army]] of one million troops.<ref name="ebrey east asia 271">Ebrey (2006), 271.</ref> Although private maritime trade and official tribute missions from China had taken place in previous dynasties, the tributary fleet under the [[Muslim]] [[eunuch]] admiral [[Zheng He]] in the 15th century surpassed all others in sheer size. There were enormous projects of construction, including the restoration of the [[Grand Canal of China|Grand Canal]] and the [[Great Wall of China|Great Wall]] and the establishment of the [[Forbidden City]] in Beijing during the first quarter of the 15th century. Estimates for the population in the late Ming era vary from 160 to 200 million.<ref>For the lower population estimate, see {{Harvcol|Fairbank|Goldman|2006|pp=128}}, for the higher estimate see {{Harvcol|Ebrey|1999|pp=197}}.</ref> The [[University of Calgary]] states that "the Ming created one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/eurvoya/ming.html|title=The European Voyages of Exploration & The Ming Dynasty's Maritime History|publisher=The [[University of Calgary]]|accessdate=2008-06-27}}</ref> |

|||

== Redirect Pages == |

|||

[[Hongwu Emperor|Emperor Hongwu]] (r. 1368–1398) attempted to create a society of self-sufficient rural communities in a rigid, immobile system that would have no need to engage with the commercial life and trade of urban centers. His rebuilding of China's agricultural base and strengthening of communication routes through the militarized [[courier]] system had the unintended effect of creating a vast agricultural surplus that could be sold at burgeoning markets located along courier routes. Rural culture and commerce became influenced by urban trends. The upper echelons of society embodied in the [[Gentry (China)|scholarly gentry class]] were also affected by this new consumption-based culture. In a departure from tradition, merchant families began to produce examination candidates to become [[Scholar-bureaucrats|scholar-officials]] and adopted cultural traits and practices typical of the gentry class. Parallel to this trend involving social class and commercial consumption were changes in social and political philosophy, bureaucracy and governmental institution, and even arts and literature. |

|||

Please do not create redirect pages that redirect to nonexistent pages. They will be deleted. Addtitionally if these are test pages, please do not create test pages as they will also be deleted. [[User:Xp54321|<font color="191970">'''Xp54321''']]</font><sup> ([[User talk:Xp54321|<font color="FF8C00">'''''Hello!'''''</font>]] • [[Special:Contributions/Xp54321|<font color="FF8C00">'''''Contribs'''''</font>]])</sup> 22:34, 3 July 2008 (UTC) |

|||

By the 16th century the Ming economy was stimulated by maritime trade with the [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]], [[Spanish Empire|Spanish]], and [[Dutch Republic|Dutch]]. China became involved in a new global trade of goods, plants, animals, and food crops known as the [[Columbian Exchange]]. Trade with [[Early Modern Europe|European powers]] and the [[Japan]]ese brought in massive amounts of [[silver]], which then replaced copper and paper [[banknote]]s as the common [[medium of exchange]] in China. During the last decades of the Ming the flow of silver into China was greatly diminished, thereby undermining state revenues and indeed the entire Ming economy. This damage to the economy was compounded by the effects on agriculture of the incipient [[Little Ice Age]], natural calamities, crop failure, and sudden epidemics. The ensuing breakdown of authority and people's livelihoods allowed rebel leaders such as Li Zicheng to challenge Ming authority. |

|||

== [[Wikipedia: WikiProject Red Link Recovery]] == |

|||

howdy are how you guys doing? |

|||

There is no need to make redirects for the red links that only one or two articles link to. In those cases you need to go into the article and edit the red links to the correct links. |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Main|History of the Ming Dynasty}} |

|||

{{See|List of Emperors of the Ming Dynasty}} |

|||

===Founding=== |

|||

====Revolt and rebel rivalry==== |

|||

The [[Mongol Empire|Mongol]]-led [[Yuan Dynasty]] (1271–1368) ruled before the establishment of the Ming Dynasty. Alongside institutionalized ethnic discrimination against [[Han Chinese]] that stirred resentment and rebellion, other explanations for the Yuan's demise included overtaxing areas hard-hit by crop failure, [[inflation]], and massive flooding of the [[Yellow River]] as a result of the abandonment of irrigation projects.<ref name="gascoigne 150"/> Consequently, agriculture and the economy were in shambles and rebellion broke out among the hundreds of thousands of peasants called upon to work on repairing the dykes of the Yellow River.<ref name="gascoigne 150">Gascoigne, 150.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Chinese Cannon.JPG|thumb|left|170px|A [[cannon]] from the ''[[Huolongjing]]'', compiled by [[Jiao Yu]] and [[Liu Ji]] before the latter's death in 1375.]] |

|||

From the top of the page: "Pick any entry in the list below. If the red link noted is incorrect fix it, for example by adding a missing character. Even if the resulting link is still red, fixing the link may encourage someone to write the missing article." |

|||

A number of Han Chinese groups revolted, including the [[Red Turban Rebellion|Red Turbans]] (红巾军) in 1351. The Red Turbans were affiliated with the [[White Lotus]], a [[Chinese Buddhism|Buddhist]] secret society. Zhu Yuanzhang was a penniless peasant and Buddhist monk who joined the Red Turbans in 1352, but soon gained a reputation after marrying the foster daughter of a rebel commander.<ref>Ebrey (1999), 190–191.</ref> In 1356 Zhu's rebel force captured the city of [[Nanjing]],<ref name="gascoigne 151">Gascoigne 151.</ref> which he would later establish as the capital of the Ming Dynasty. |

|||

Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋) cemented his power in the south by eliminating his arch rival and rebel leader [[Chen Youliang]] (陈友谅) in the [[Battle of Lake Poyang]] (鄱阳湖水战) in 1363. After the dynastic head of the Red Turbans suspiciously died in 1367 while hosted as a guest of Zhu, the latter made his imperial ambitions known by sending an army toward the Yuan capital in 1368.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 191">Ebrey (1999), 191.</ref> The last Yuan emperor fled north to [[Shangdu]] and Zhu declared the founding of the Ming Dynasty after razing the Yuan palaces of [[Khanbaliq]] (Beijing) to the ground.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 191"/> |

|||

For the Unlikely brackets category most of the red links just need a "(" or a ")" to direct them to the right page. [[User:Aspects|Aspects]] ([[User talk:Aspects|talk]]) 22:46, 3 July 2008 (UTC) |

|||

Instead of the traditional way of naming a dynasty after the first ruler's home district, Zhu's choice of 'Ming' or 'Brilliant' for his dynasty followed a Mongol precedent of an uplifting title.<ref name="gascoigne 151"/> Zhu Yuanzhang also took [[Hongwu Emperor|Hongwu]], or 'Vastly Martial' as his reign title. Although the White Lotus had fomented his rise to power, Hongwu later denied that he had ever been a member of their organization and suppressed the religious movement after he became emperor.<ref name="gascoigne 151"/><ref name="wakeman">Wakeman, 207.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Information.svg|25px]] Welcome to Wikipedia. It might not have been your intention, but your recent edit removed content from {{#if:Black hole|[[:Black hole]]|Wikipedia}}. When removing text, please specify a reason in the [[Help:Edit summary|edit summary]] and discuss edits that are likely to be controversial on the article's [[Wikipedia:Talk page|talk page]]. If this was a mistake, don't worry; the text has been restored, as you can see from the [[Help:Page history|page history]]. Take a look at the [[Wikipedia:Welcome|welcome page]] to learn more about contributing to this encyclopedia, and if you would like to experiment, please use the [[Wikipedia:Sandbox|sandbox]]. {{#if:|{{{2}}}|Thank you.}}<!-- Template:uw-delete1 --> A link to the edit I have reverted can be found here: <span class="plainlinks">[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_hole&diff=next&oldid=227989103 link]</span>. If you believe this edit should not have been reverted, please contact me. <!-- 65--> [[User:Spinningspark|<font style="background:#FFF090;color:#00C000">'''Sp<font style="background:#FFF0A0;color:#80C000">in<font style="color:#C08000">ni</font></font><font style="color:#C00000">ng</font></font><font style="color:#2820F0">Spark'''</font>]] 16:45, 27 July 2008 (UTC) |

|||

====Reign of the Hongwu Emperor==== |

|||

==Proposed deletion of [[Properties of black holes]]== |

|||

[[Image:Hongwu1.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Portrait of the [[Hongwu Emperor]] (r. 1368 - 1398)]] |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning yellow.svg|left|48px|]] |

|||

Hongwu immediately set to rebuilding state infrastructure. He built a 48 km (30 mile) long [[City Wall of Nanjing|wall around Nanjing]], as well as new palaces and government halls.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 191"/> The ''[[History of Ming|Mingshi]]'' 明史 states that as early as 1364 Zhu Yuanzhang had begun drafting a new [[Confucianism|Confucian]] law code known as the ''Daming Lu'', which was completed by 1397 and repeated certain clauses found in the old [[Tang Code]] of 653.<ref name="andrew rapp 25">Andrew & Rapp, 25.</ref> Hongwu organized a military system known as the ''weisuo'', which was similar to the [[Fubing system|''fubing'' system]] of the [[Tang Dynasty]] (618–907). The goal was to have soldiers become self-reliant farmers in order to sustain themselves while not fighting or training.<ref name="fairbank 129">Fairbank, 129.</ref> The system of the self-sufficient agricultural soldier, however, was largely a farce; infrequent rations and awards were not enough to sustain the troops, and many deserted their ranks if they weren't located in the heavily-supplied frontier.<ref name="fairbank 134"/> |

|||

A [[Wikipedia:Proposed deletion|proposed deletion]] template has been added to the article [[Properties of black holes]], suggesting that it be deleted according to the proposed deletion process. All contributions are appreciated, but this article may not satisfy Wikipedia's [[Wikipedia:Criteria for inclusion|criteria for inclusion]], and the deletion notice should explain why (see also "[[Wikipedia:What Wikipedia is not|What Wikipedia is not]]" and [[Wikipedia:Deletion policy|Wikipedia's deletion policy]]). You may prevent the proposed deletion by removing the <code>{{[[Template:dated prod|dated prod]]}}</code> notice, but please explain why you disagree with the proposed deletion in your edit summary or on [[Talk:Properties of black holes|its talk page]]. |

|||

Although a Confucian, Hongwu had a deep distrust for the [[Scholar-bureaucrats|scholar-officials]] of the [[Gentry (China)|gentry class]] and was not afraid to have them beaten in court for offenses.<ref name="ebrey 191 193">Ebrey (1999), 191–192.</ref> He halted the [[Imperial examinations|civil service examinations]] in 1373 after complaining that the 120 scholar-officials who obtained a ''jinshi'' degree were incompetent ministers.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 192">Ebrey (1999), 192.</ref><ref name="hucker 13">Hucker, 13.</ref> After the examinations were reinstated in 1384,<ref name="hucker 13"/> he had the chief examiner executed after it was discovered that he allowed only candidates from the south to be granted ''jinshi'' degrees.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 192"/> |

|||

Please consider improving the article to address the issues raised because even though removing the deletion notice will prevent deletion through the [[WP:PROD|proposed deletion process]], the article may still be deleted if it matches any of the [[Wikipedia:Criteria for speedy deletion|speedy deletion criteria]] or it can be sent to [[Wikipedia:Articles for deletion|Articles for Deletion]], where it may be deleted if [[Wikipedia:Consensus|consensus]] to delete is reached.<!-- {{PRODWarning|Properties of black holes}} --> [[User:Spinningspark|<font style="background:#FFF090;color:#00C000">'''Sp<font style="background:#FFF0A0;color:#80C000">in<font style="color:#C08000">ni</font></font><font style="color:#C00000">ng</font></font><font style="color:#2820F0">Spark'''</font>]] 17:14, 27 July 2008 (UTC) |

|||

In 1380 Hongwu had the Chancellor Hu Weiyong (左丞相 胡惟庸) executed upon suspicion of a conspiracy plot to overthrow him; after that Hongwu abolished the [[Chancellor of China|Chinese Chancellery]] and assumed this role as chief executive and emperor.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 192 193">Ebrey (1999), 192–193.</ref><ref>Fairbank, 130.</ref> With a growing suspicion of his ministers and subjects, Hongwu established the [[Jinyi Wei]] (锦衣卫), a network of [[secret police]] drawn from his own palace guard. They were partly responsible for the loss of 100,000 lives in several purges over three decades of his rule.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 192 193"/><ref>Fairbank, 129–130.</ref> |

|||

==Proposed deletion of [[2021 in sports]]== |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning yellow.svg|left|48px|]] |

|||

A [[Wikipedia:Proposed deletion|proposed deletion]] template has been added to the article [[2021 in sports]], suggesting that it be deleted according to the proposed deletion process. All contributions are appreciated, but this article may not satisfy Wikipedia's [[Wikipedia:Criteria for inclusion|criteria for inclusion]], and the deletion notice should explain why (see also "[[Wikipedia:What Wikipedia is not|What Wikipedia is not]]" and [[Wikipedia:Deletion policy|Wikipedia's deletion policy]]). You may prevent the proposed deletion by removing the <code>{{tl|dated prod}}</code> notice, but please explain why you disagree with the proposed deletion in your edit summary or on [[Talk:2021 in sports|its talk page]]. |

|||

====South-Western Frontier==== |

|||

Please consider improving the article to address the issues raised because even though removing the deletion notice will prevent deletion through the [[WP:PROD|proposed deletion process]], the article may still be deleted if it matches any of the [[Wikipedia:Criteria for speedy deletion|speedy deletion criteria]] or it can be sent to [[Wikipedia:Articles for deletion|Articles for Deletion]], where it may be deleted if [[Wikipedia:Consensus|consensus]] to delete is reached.<!-- Template:PRODWarning --> --[[User:Alinnisawest|Alinnisawest]]([[User talk:Alinnisawest|talk]]) 21:16, 12 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

[[Image:Dali-puerta-sur-c01.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The old south gate of [[Dali, Yunnan]], which was established as a Chinese-style city in 1382 shortly after the Ming conquest of the region.]] |

|||

In 1381, the Ming Dynasty annexed the areas of the southwest that had once been part of the [[Kingdom of Dali]]. By the end of the 14th century, some 200,000 military colonists settled some 2,000,000 ''mu'' (350,000 acres) of land in what is now [[Yunnan]] and [[Guizhou]].<ref name="ebrey cambridge 195">Ebrey (1999), 195.</ref> Roughly half a million more Chinese settlers came in later periods; these migrations caused a major shift in the ethnic make-up of the region, since more than half of the roughly 3,000,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty were non-Han peoples.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 195"/> In this region, the Ming government adopted a policy of dual administration. Areas with majority ethnic Chinese were governed according to Ming laws and policies; areas where native tribal groups dominated had their own set of laws while [[tusi|tribal chiefs]] promised to maintain order and send tribute to the Ming court in return for needed goods.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 195"/> From 1464 to 1466 the [[Miao people|Miao]] and [[Yao people]] revolted against what they saw as oppressive government rule; in response, the Ming government sent an army of 30,000 troops (including 1,000 Mongols) to join the 160,000 local troops of [[Guangxi]] and crushed the rebellion.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 197">Ebrey (1999), 197.</ref> After the scholar and philosopher [[Wang Yangming]] (1472–1529) suppressed another rebellion in the region, he advocated joint administration of Chinese and local ethnic groups in order to bring about [[Sinicization|sinification]] in the local peoples' culture.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 197"/> |

|||

==Speedy deletion of [[:2021 in sports]]== |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning_pn.svg|48px|left]] A tag has been placed on [[:2021 in sports]] requesting that it be speedily deleted from Wikipedia. This has been done under [[WP:CSD#A3|section A3 of the criteria for speedy deletion]], because it is an article with no content whatsoever, or whose contents consist only of external links, "See also" section, book reference, category tag, template tag, interwiki link, rephrasing of the title, or an attempt to contact the subject of the article. Please see [[Wikipedia:Stub#Essential information about stubs|Wikipedia:Stub]] for our minimum information standards for short articles. Also please note that articles must be on [[Wikipedia:Notability|notable]] subjects and should provide references to [[Wikipedia:Reliable sources|reliable sources]] that [[Wikipedia:Verifiability|verify]] their content. |

|||

====Relations with Tibet==== |

|||

If you think that this notice was placed here in error, you may contest the deletion by adding <code>{{tl|hangon}}</code> to '''the top of [[:2021 in sports|the page that has been nominated for deletion]]''' (just below the existing speedy deletion or "db" tag), coupled with adding a note on '''[[ Talk:2021 in sports|the talk page]]''' explaining your position, but be aware that once tagged for ''speedy'' deletion, if the article meets the criterion it may be deleted without delay. Please do not remove the speedy deletion tag yourself, but don't hesitate to add information to the article that would would render it more in conformance with Wikipedia's policies and guidelines. Lastly, please note that if the article does get deleted, you can contact [[:Category:Wikipedia administrators who will provide copies of deleted articles|one of these admins]] to request that a copy be emailed to you. <!-- Template:Db-nocontent-notice --> <!-- Template:Db-csd-notice-custom --> --[[User:cocomonkilla|Cocomonkilla]] <sup>([[User_talk:Cocomonkilla|talk]]) ([[Special:Contributions/Cocomonkilla|contrib]])</sup> 21:22, 12 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

{{main|Tibet during the Ming Dynasty}} |

|||

[[Image:17th century Central Tibeten thanka of Guhyasamaja Akshobhyavajra, Rubin Museum of Art.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A 17th century Tibetan [[thangka]] of Guhyasamaja Akshobhyavajra; the Ming Dynasty court gathered various tribute items which were native products of Tibet (such as thangkas),<ref name="information office of the state council 73">Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, ''Testimony of History'', 73. </ref> and in return granted Tibetan tribute-bearers with gifts.<ref>Wang Jiawei & Nyima Gyaincain, ''The Historical Status of China's Tibet'' (China Intercontinental Press, 1997), 39–41.</ref>]] |

|||

Scholarship outside China generally regards Tibet as having been independent during the Ming Dynasty, whereas historians in China today take an opposing point of view. The ''[[History of Ming|Mingshi]]''— the official history of the Ming Dynasty compiled later by the [[Qing Dynasty]] in 1739—states that the Ming established itinerant commanderies overseeing Tibetan administration while also renewing titles of ex-Yuan Dynasty officials from [[Tibet]] and conferring new princely titles on leaders of [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibet's Buddhist sects]].<ref name="mingshi">''[[Mingshi]]''-Geography I «明史•地理一»: 東起朝鮮,西據吐番,南包安南,北距大磧。; Geography III «明史•地理三»: 七年七月置西安行都衛於此,領河州、朵甘、烏斯藏、三衛。; Western territory III «明史•列傳第二百十七西域三»</ref> However, Turrell V. Wylie states that [[censorship]] in the ''Mingshi'' in favor of bolstering the Ming emperor's prestige and reputation at all costs obfuscates the nuanced history of Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming era.<ref name="wylie 470"/> Modern scholars still debate on whether or not the Ming Dynasty really had [[sovereignty]] over Tibet at all, as some believe it was a relationship of loose [[suzerainty]] which was largely cut off when the [[Jiajing Emperor]] (r. 1521–1567) persecuted Buddhism in favor of [[Daoism]] at court.<ref name="wang nyima 1 40">Wang & Nyima, 1–40.</ref><ref name="laird 106 107">Laird, 106–107.</ref><ref name="wylie 470">Wylie, 470.</ref> Helmut Hoffman states that the Ming upheld the facade of rule over Tibet through periodic missions of "tribute emissaries" to the Ming court and by granting nominal titles to ruling lamas, but did not actually interfere in Tibetan governance.<ref name="Hoffman 65">Hoffman, 65.</ref> Wang Jiawei and Nyima Gyaincain disagree, stating that Ming China had sovereignty over Tibetans who did not inherit Ming titles, but were forced to travel to Beijing to renew them.<ref name="wang nyima 37">Wang & Nyima, 37.</ref> Melvyn C. Goldstein writes that the Ming had no real administrative authority over Tibet since the various titles given to Tibetan leaders already in power did not confer authority as earlier Mongol Yuan titles had; according to him, "the Ming emperors merely recognized political reality."<ref name="goldstein 4 5">Goldstein, 4–5.</ref> Some scholars argue that the significant religious nature of the relationship of the Ming court with Tibetan lamas is underrepresented in modern scholarship.<ref name="norbu 52">Norbu, 52.</ref><ref name="kolmas 32">Kolmas, 32.</ref> Others underscore the commercial aspect of the relationship, noting the Ming Dynasty's insufficient amount of horses and the need to maintain the [[Tibet during the Ming Dynasty#Tribute and exchanging tea for horses|tea-horse trade]] with Tibet.<ref name="wang nyima 39">Wang & Nyima, 39–40.</ref><ref name="sperling 474 475">Sperling, 474–475, 478.</ref><ref name="perdue 273">Perdue, 273.</ref><ref name="kolmas 28 29">Kolmas, 28–29.</ref><ref name="laird 131">Laird, 131</ref> Scholars also debate on how much power and influence—if any—the Ming Dynasty court had over the ''de facto'' successive ruling families of Tibet, the Phagmodru (1354–1436), Rinbung (1436–1565), and Tsangpa (1565–1642).<ref name="kolmas 29">Kolmas, 29.</ref><ref name="chan 262">Chan, 262.</ref><ref name="norbu 58">Norbu, 58.</ref><ref name="laird 137"/><ref name="wang nyima 42">Wang & Nyima, 42.</ref><ref name="dreyfus 504">Dreyfus, 504.</ref> |

|||

==Speedy deletion of [[:September 2021]]== |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning_pn.svg|48px|left]] A tag has been placed on [[:September 2021]] requesting that it be speedily deleted from Wikipedia. This has been done under [[WP:CSD#A3|section A3 of the criteria for speedy deletion]], because it is an article with no content whatsoever, or whose contents consist only of external links, "See also" section, book reference, category tag, template tag, interwiki link, rephrasing of the title, or an attempt to contact the subject of the article. Please see [[Wikipedia:Stub#Essential information about stubs|Wikipedia:Stub]] for our minimum information standards for short articles. Also please note that articles must be on [[Wikipedia:Notability|notable]] subjects and should provide references to [[Wikipedia:Reliable sources|reliable sources]] that [[Wikipedia:Verifiability|verify]] their content. |

|||

The Ming initiated sporadic armed intervention in Tibet during the 14th century, while at times the Tibetans also used successful armed resistance against Ming forays.<ref name="langlois">Langlois, 139 & 161.</ref><ref name="geiss 417 418">Geiss, 417–418.</ref> Patricia Ebrey, Thomas Laird, Wang Jiawei, and Nyima Gyaincain all point out that the Ming Dynasty did not garrison permanent troops in Tibet,<ref name="ebrey 1999 227">Ebrey (1999), 227.</ref><ref name="laird 137">Laird, 137.</ref><ref name="wang nyima 38">Wang & Nyima, 38.</ref> unlike the former Mongol Yuan Dynasty.<ref name="laird 137"/> The [[Wanli Emperor]] (r. 1572–1620) made attempts to reestablish Sino-Tibetan relations in the wake of a [[History of Tibet#The origin of the title of 'Dalai Lama'|Mongol-Tibetan alliance]] initiated in 1578, the latter of which affected the foreign policy of the subsequent Manchu [[Qing Dynasty]] (1644–1912) of China in their support for the [[Dalai Lama]] of the [[Gelug|Yellow Hat]] sect. <ref name="wylie 470"/><ref name="kolmas 31">Kolmas, 30–31.</ref><ref name="goldstein 8">Goldstein, 8.</ref><ref name="laird 143 144">Laird, 143–144.</ref><ref name="The Ming Biographical History Project of the Association for Asian Studies 23">The Ming Biographical History Project of the Association for Asian Studies, ''Dictionary of Ming Biography'', 23.</ref> By the late 16th century, the Mongols proved to be successful armed protectors of the Yellow Hat Dalai Lama after their increasing presence in the [[Amdo]] region, culminating in [[Güshi Khan]]'s (1582–1655) [[Tibet during the Ming Dynasty#Civil war and Güshi Khan|conquest of Tibet in 1642]].<ref name="wylie 470"/><ref name="kolmas 34 35">Kolmas, 34–35.</ref><ref name="goldstein 6 8">Goldstein, 6–9.</ref><ref name="laird 152">Laird, 152.</ref> |

|||

If you think that this notice was placed here in error, you may contest the deletion by adding <code>{{tl|hangon}}</code> to '''the top of [[:September 2021|the page that has been nominated for deletion]]''' (just below the existing speedy deletion or "db" tag), coupled with adding a note on '''[[ Talk:September 2021|the talk page]]''' explaining your position, but be aware that once tagged for ''speedy'' deletion, if the article meets the criterion it may be deleted without delay. Please do not remove the speedy deletion tag yourself, but don't hesitate to add information to the article that would would render it more in conformance with Wikipedia's policies and guidelines. Lastly, please note that if the article does get deleted, you can contact [[:Category:Wikipedia administrators who will provide copies of deleted articles|one of these admins]] to request that a copy be emailed to you. <!-- Template:Db-nocontent-notice --> <!-- Template:Db-csd-notice-custom --> --[[User:Alinnisawest|Alinnisawest]]([[User talk:Alinnisawest|talk]]) 21:37, 12 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

===Reversal of Hongwu's policies=== |

|||

== August 2008 == |

|||

====Imposing standards and relocations==== |

|||

[[Image:Information.svg|25px]] Please do not delete content or templates from pages on Wikipedia{{#if:Joe jonas|, as you did to [[:Joe jonas]],}} without giving a valid reason for the removal in the [[Help:Edit summary|edit summary]]. Your content removal does not appear constructive, and has been [[Help:Reverting|reverted]]. Please make use of the [[Wikipedia:Sandbox|sandbox]] if you'd like to experiment with test edits. {{#if:|{{{2}}}|Thank you.}}<!-- Template:uw-delete2 --> ''I changed the content for a [[WP:REDIRECT|redirection]], as the page was about a subject already on Wikipedia. Could you explain your reasoning for changing the back to a previous revision and then adding a deletion tag?'' [[User:Booglamay|<b style="color:#bdd8e7">B</b><b style="color:#9bc6de">o</b><b style="color:#74aecf">o</b><b style="color:#4d97c1">g</b><b style="color:#3485b3">l</b><b style="color:#1f6e9c">a</b><b style="color:#0b5a88">m</b><b style="color:#013d5f">a</b><b style="color:#003d60">y</b>]] (<font style="color:#6699cc">[[User talk:Booglamay|talk]] '''·''' [[Special:Contributions/Booglamay|contributions]]</font>) - 23:14, 13 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

[[Image:Nj02.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The [[City Wall of Nanjing]]]] |

|||

According to historian Timothy Brook, the Hongwu Emperor attempted to immobilize society by creating rigid, state-regulated boundaries between villages and larger townships, discouraging trade and travel in society not permitted by the government.<ref name="brook 19">Brook, 19.</ref> Hongwu attempted to instill austere values by imposing uniform dress codes, standard methods of speech, and standard style of writing [[Chinese literature#Classical prose|classical prose]] that did not flaunt the skills of the highly educated.<ref name="brook 30 32">Brook, 30–32.</ref> His suspicion for the educated elite matched his disdain for the commercial elites, imposing inordinately high taxes upon the hotbed of powerful merchant families in the region of [[Suzhou]] in [[Jiangsu]].<ref name="ebrey cambridge 192"/> He also forcibly moved thousands of wealthy families from the southeast and resettled them around Nanjing in the [[Jiangnan]] region, forbidding them to move once they were settled.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 192"/><ref name="brook 28 29">Brook, 28–29.</ref> To keep track of the merchants' activities, Hongwu forced them to register all of their goods once a month.<ref name="brook 65 67">Brook, 65–67.</ref> One of his main goals as ruler was to permanently curb the influence of merchants and landlords, yet several of his policies would eventually encourage them to amass more wealth. |

|||

Hongwu's oppressive system of massive relocation and the desire to escape his harsh taxes encouraged many to become [[itinerant]] retailers, peddlers, or migrant workers finding tenant landowners who would rent them space to farm and labor on.<ref>Brook, 27–28, 94–95.</ref> By the mid Ming era, emperors had abandoned Hongwu's relocation scheme and instead trusted local officials to document migrant workers in order to bring in more revenue.<ref name = "brook 97"/> An elite of wealthy landlords and merchants reigning over land tenants, wage laborers, domestic servants, and migrant workers was hardly the vision of Hongwu's: strict adherence to the hierarchic status system of the [[four occupations]].<ref>Brook, 85, 146, 154.</ref> |

|||

==Speedy deletion of [[:Document conversion]]== |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning_pn.svg|48px|left]] A tag has been placed on [[:Document conversion]], requesting that it be speedily deleted from Wikipedia. This has been done under [[WP:CSD#G11|section G11 of the criteria for speedy deletion]], because the article seems to be blatant advertising which only promotes a company, product, group, service or person and would need to be fundamentally rewritten in order to become an encyclopedia article. Please read [[Wikipedia:Spam|the guidelines on spam]] as well as the [[Wikipedia:Business' FAQ]] for more information. |

|||

====Self-sufficient agriculture, surplus, and urban trends==== |

|||

If you think that this notice was placed here in error, you may contest the deletion by adding <code>{{tl|hangon}}</code> to '''the top of [[:Document conversion|the page that has been nominated for deletion]]''' (just below the existing speedy deletion or "db" tag), coupled with adding a note on '''[[ Talk:Document conversion|the talk page]]''' explaining your position, but be aware that once tagged for ''speedy'' deletion, if the article meets the criterion it may be deleted without delay. Please do not remove the speedy deletion tag yourself, but don't hesitate to add information to the article that would would render it more in conformance with Wikipedia's policies and guidelines. Lastly, please note that if the article does get deleted, you can contact [[:Category:Wikipedia administrators who will provide copies of deleted articles|one of these admins]] to request that a copy be emailed to you. <!-- Template:Db-spam-notice --> <!-- Template:Db-csd-notice-custom --> [[User:Minkythecat|Minkythecat]] ([[User talk:Minkythecat|talk]]) 10:33, 14 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

[[Image:Porcelaine chinoise Guimet 271108.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A [[Chinese ceramics|porcelain]] vase from the [[Jiajing Emperor|Jiajing reign period]] (1521–1567); Chinese culture became a consumptionary-based culture by the late Ming. Social elites were expected to know the difference between shoddy crafts and fine wares, and even which type of plants were to be appreciated as rare and exotic enough for [[Chinese garden|one's garden]].<ref>Brook, 136–137.</ref>]] |

|||

Hongwu revived the agricultural sector to create self-sufficient communities that would not rely on commerce, which he assumed would remain only in urban areas.<ref name="brook 69">Brook, 69.</ref> Yet the surplus created from this revival encouraged rural farmers to make profits by first selling their goods at thoroughfares; by the mid Ming era they began selling their goods in regional urban markets.<ref>Brook, 65–66, 112–113.</ref> As the countryside and urban areas became more connected through commerce, households in rural areas began taking on traditionally urban specializations, such as production of silk and cotton textiles.<ref>Brook, 113–117.</ref> By the late Ming there was a growing concern amongst conservative Confucians that the metaphorical delicate fabric holding together the communal social order was being undermined by country rustics accepting every manner of urban life and decadence.<ref name="brook 124 125">Brook, 124–125.</ref> |

|||

The rural farmer was not the only social group affected by growing commercialization of Chinese society; it also heavily influenced the landholding gentry that traditionally produced scholar-officials for [[civil service]]. The scholar-officials were traditionally held as frugal individuals who deterred themselves from arrogance in the wealth garnered from a prestigious career; they were known even to walk from their country homes into the city where they were employed.<ref name="brook 144 145">Brook, 144–145.</ref> By the time of the [[Zhengde Emperor]] (1505–1521), officials chose to be hauled around in luxurious [[Litter (vehicle)|sedan chairs]] and began purchasing lavish homes in affluent urban neighborhoods instead of living in the countryside.<ref name="brook 144 145"/> By the late Ming era, gaining wealth became the prime indicator of social prestige, even more so than gaining a scholarly degree.<ref>Brook, 128, 144.</ref> |

|||

==[[:September 2021]]== |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning pn.svg|left|48px|]]<!-- use [[Image:Ambox warning yellow.svg|left|48px|]] for YELLOW flag --> |

|||

A tag has been placed on [[:September 2021]], requesting that it be speedily deleted from Wikipedia. This has been done under the [[WP:CSD#Articles|criteria for speedy deletion]], because it is a very short article providing no content to the reader. Please note that external links, "See also" section, book reference, category tag, template tag, interwiki link, rephrasing of the title, or an attempt to contact the subject of the article don't count as content. Please see [[Wikipedia:Stub#Essential information about stubs|Wikipedia:Stub]] for our minimum information standards for short articles. Also please note that articles must be on [[Wikipedia:Notability|notable]] subjects and should provide references to [[Wikipedia:Reliable sources|reliable sources]] that [[Wikipedia:Verifiability|verify]] their content. |

|||

====Fusion of the merchant and gentry classes==== |

|||

Please do not remove the speedy deletion tag yourself. If you plan to expand the article, you can request that [[Wikipedia:Administrators|administrators]] wait a while for you to add contextual material. To do this, affix the template '''<code>{{tl|hangon}}</code>''' to the page and state your intention on the article's [[Help:Talk page|talk page]]. Feel free to leave a note on my talk page if you have any questions about this.<!-- Template:Empty-warn --> [[User:Apparition11|Apparition11]] ([[User talk:Apparition11|talk]]) 14:10, 14 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

[[Image:旋转 DSCN1782.JPG|thumb|right|200px|[[Pagoda of Cishou Temple|Cishou Temple Pagoda]], built in 1576; the Chinese believed that building pagodas on certain sites according to [[Feng shui|geomantic principles]] brought about auspicious events;<ref name="brook 7">Brook, 7.</ref> merchant-funding for such projects was needed by the late Ming period.]] |

|||

In the first half of the Ming era, scholar-officials would rarely mention the contribution of merchants in society while writing their local [[gazetteer]];<ref name="brook 73">Brook, 73.</ref> officials were certainly capable of funding their own public works projects, a symbol of their virtuous political leadership.<ref>Brook, 6–7, 90–91.</ref> However, by the second half of the Ming era it became common for officials to solicit money from merchants in order to fund their various projects, such as building bridges or establishing new schools of Confucian learning for the betterment of the gentry.<ref name="brook 90 93">Brook, 90–93.</ref> From that point on the gazetteers began mentioning merchants and often in high esteem, since the wealth produced by their economic activity produced resources for the state as well as increased production of books needed for the education of the gentry.<ref>Brook, 90–93, 129–130, 151.</ref> Merchants began taking on the highly-cultured, [[connoisseur]]'s attitude and cultivated traits of the gentry class, blurring the lines between merchant and gentry and paving the way for merchant families to produce scholar-officials.<ref>Brook, 128–129, 134–138.</ref> The roots of this social transformation and class indistinction [[Society of the Song Dynasty#Social class|could be found in the Song Dynasty]] (960–1279),<ref>Gernet, 60–61, 68–69.</ref> but it became much more pronounced in the Ming. Writings of family instructions for lineage groups in the late Ming period display the fact that one no longer inherited his position in the categorization of the four occupations (in descending order): [[Four occupations#The shi (士)|gentry]], [[Four occupations#The nong (农)|farmers]], [[Four occupations#The gong (工)|artisans]], and [[Four occupations#The shang (商)|merchants]].<ref name="brook 161">Brook, 161.</ref> |

|||

====Courier network and commercial growth==== |

|||

:In regards to articles like these, they are not yet notable enough for inclusion in Wikipedia. If you can't put anything on the page, likely you shouldn't create it. Cheers. <font color="green">[[User:Lifebaka|''lifebaka'']]</font>[[User talk:Lifebaka|'''++''']] 14:39, 14 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

Hongwu believed that only government [[courier]]s and lowly retail merchants should have the right to travel far outside their home town.<ref name="brook 65 67"/> Despite his efforts to impose this view, his building of an efficient communication network for his military and official personnel strengthened and fomented the rise of a potential commercial network running parallel to the courier network.<ref>Brook, 10, 49–51, 56.</ref> The shipwrecked Korean [[Choe Bu]] (1454–1504) remarked in 1488 how the locals along the eastern coasts of China did not know the exact distances between certain places, which was virtually exclusive knowledge of the [[Three Departments and Six Ministries|Ministry of War]] and courier agents.<ref name="brook 40 43">Brook, 40–43.</ref> This was in stark contrast to the late Ming period, when merchants not only traveled further distances to convey their goods, but also bribed courier officials to use their routes and even had printed geographical guides of commercial routes that imitated the couriers' maps.<ref>Brook, 10, 118–119.</ref> |

|||

====Merchants, an open market, and silver==== |

|||

== Speedy deletion tags == |

|||

[[Image:MingLacquerTable1.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The only surviving piece of furniture from the "Orchard Factory" (the Imperial [[Lacquer]] Workshop) set up in [[Beijing]] in the early Ming Dynasty. Decorated in [[dragon]]s and [[Phoenix (mythology)|phoenixes]], it was made during the [[Xuande Emperor|Xuande]] era (1426–1435). The imperial workshops in the Ming era were overseen by a eunuch bureau.<ref name="hucker 25"/> ([[media:MingLacquerTable2.jpg|See closeup for detail]])]] |

|||

The scholar-officials' dependence upon the economic activities of the merchants became more than a trend when it was semi-institutionalized by the state in the mid Ming era. Qiu Jun (1420–1495), a scholar-official from [[Hainan]], argued that the state should only mitigate market affairs during times of pending crisis and that merchants were the best gauge in determining the strength of a nation's riches in resources.<ref name="brook 102">Brook, 102.</ref> The government followed this guideline by the mid Ming era when it allowed merchants to take over the state [[monopoly]] of salt production. This was a gradual process where the state supplied northern frontier armies with enough grain by granting merchants licenses to trade in salt in return for their shipping services.<ref name="brook 108">Brook, 108.</ref> The state realized that merchants could buy salt licenses with silver and in turn boost state revenues to the point where buying grain was not an issue.<ref name="brook 108"/> The governments of both Hongwu and [[Zhengtong]] (r. 1435–1449) attempted to cut the flow of silver into the economy in favor of [[Banknote|paper currency]], yet mining the precious metal simply became a lucrative illegal pursuit practiced by many.<ref>Brook, 68–69, 81–83.</ref> Hongwu was unaware of economic inflation even as he continued to hand out multitudes of banknotes as awards; by 1425, paper currency was worth only 0.025% to 0.014% its original value in the 14th century.<ref name="fairbank 134">Fairbank, 134.</ref> The value of standard copper coinage dropped significantly as well due to [[counterfeit]] minting; by the 16th century, new maritime trade contacts with Europe provided massive amounts of imported silver, which increasingly became the common [[medium of exchange]].<ref name="fairbank 134 135">Fairbank, 134–135.</ref> As far back as 1436, the southern grain tax had been partially commuted to payments in silver.<ref name="brook xx">Brook, xx.</ref> In 1581 the Single Whip Reform installed by [[Grand Secretary]] [[Zhang Juzheng]] (1525–1582) finally assessed taxes on the amount of land paid entirely in silver.<ref>Brook, xxi, 89.</ref> |

|||

===Reign of the Yongle Emperor=== |

|||

Thank you for helping with assessing new pages. Your changes of speedy deletion categories and the addition of templates to already tagged pages is unneccessary though, if you ask me. It doesn't help if pages are swapped from one category to another and adding an additional tag won't speed up their deletion as well. [[User:De728631|De728631]] ([[User talk:De728631|talk]]) 14:13, 14 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

[[Image:Yongle-Emperor1.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Portrait of the [[Yongle Emperor]] (r. 1402–1424).]] |

|||

====Rise to power==== |

|||

Hongwu's grandson Zhu Yunwen assumed the throne as the [[Jianwen Emperor]] (1398–1402) after Hongwu's death in 1398. In a prelude to a three-year-long civil war beginning in 1399,<ref name="robinson 2000 527">Robinson (2000), 527.</ref> Jianwen became engaged in a political showdown with his uncle Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan. Jianwen was aware of the ambitions of his princely uncles, establishing measures to limit their authority. The militant Zhu Di, given charge over the area encompassing Beijing to watch the Mongols on the frontier, was the most feared of these princes. After Jianwen arrested many of Zhu Di's associates, Zhu Di plotted a rebellion. Under the guise of rescuing the young Jianwen from corrupting officials, Zhu Di personally led forces in the revolt; the palace in Nanjing was burned to the ground, along with Zhu Di's nephew Jianwen, his wife, mother, and courtiers. Zhu Di assumed the throne as the [[Yongle Emperor]] (1402–1424); his reign is universally viewed by scholars as a "second founding" of the Ming Dynasty since he reversed many of his father's policies.<ref name="atwell 2002 84">Atwell (2002), 84.</ref> |

|||

====New capital and a restored canal==== |

|||

== Splitting Microsoft articles == |

|||

Yongle demoted Nanjing to a secondary capital and in 1403 announced the new capital of China was to be at his power base in [[Beijing]]. Construction of a new city there lasted from 1407 to 1420, employing hundreds of thousands of workers daily.<ref name="ebrey east asia 272"/> At the center was the political node of the [[Imperial City (Beijing)|Imperial City]], and at the center of this was the [[Forbidden City]], the palatial residence of the emperor and his family. By 1553, the Outer City was added to the south, which brought the overall size of Beijing to 4 by 4½ miles.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 194">Ebrey (1999), 194.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Noel 2005 Pékin tombeaux Ming voie des âmes.jpg|thumb|left|190px|The [[Ming Dynasty Tombs]] located 50 km (31 miles) north of [[Beijing]]; the site was chosen by Yongle.]] |

|||

Why do you keep creating small articles with very little information, and then undoing my attempts to merge them into bigger articles? - [[User:Josh the Nerd|Josh]] ([[User talk:Josh the Nerd|talk]] <nowiki>|</nowiki> [[Special:Contributions/Josh_the_Nerd|contribs]]) 18:00, 14 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

After laying dormant and dilapidated for decades, the [[Grand Canal (China)|Grand Canal]] was restored under Yongle from 1411–1415. The impetus for restoring the canal was to solve the perennial problem of shipping grain north to Beijing. Shipping the annual 4,000,000 ''shi'' (one shi is equal to 107 liters) was made difficult with an inefficient system of shipping grain through the [[East China Sea]] or by several different inland canals that necessitated the transferring of grain onto several different barge types in the process, including shallow and deep water barges.<ref>Brook, 46–47.</ref> Yongle commissioned some 165,000 workers to dredge the canal bed in western [[Shandong]] and built a series of fifteen [[canal lock]]s.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 194"/><ref name="brook 47">Brook, 47.</ref> The reopening of the Grand Canal had implications for Nanjing as well, as it was surpassed by the well-positioned city of [[Suzhou]] as the paramount commercial center of China.<ref name="brook 74 75">Brook, 74–75.</ref> |

|||

Although Yongle ordered episodes of bloody purges like his father—including the execution of Fang Xiaoru who refused to draft the proclamation of his succession—Yongle had a different attitude about the scholar-officials.<ref name="ebrey east asia 272">Ebrey (2006), 272.</ref> He had a selection of texts compiled from the [[Cheng Yi (philosopher)|Cheng]]-[[Zhu Xi|Zhu]] school of Confucianism—or [[Neo-Confucianism]]—in order to assist those who studied for the civil service examinations.<ref name="ebrey east asia 272"/> Yongle commissioned two thousand scholars to create a 50-million word (22,938-chapter) long encyclopedia—the ''[[Yongle Encyclopedia]]''—from seven thousand books.<ref name="ebrey east asia 272"/> This surpassed all previous encyclopedias in scope and size, including the 11th century compilation of the [[Four Great Books of Song]]. Yet the scholar-officials weren't the only political group that Yongle had to cooperate with and appease. Historian Michael Chang points out that Yongle was an "emperor on horseback" who often traversed between two capitals like in the Mongol Yuan tradition and constantly led expeditions into Mongolia.<ref name="chang 2007 66 67">Chang (2007), 66–67.</ref> This was opposed by the Confucian establishment while it served to bolster the importance of eunuchs and military officers whose power depended upon the emperor's favor.<ref name="chang 2007 66 67"/> |

|||

====Treasure fleet==== |

|||

==Repost of [[:Seed7]]== |

|||

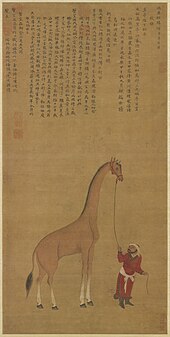

[[Image:ShenDuGiraffePainting.jpg|thumb|170px|A [[giraffe]] brought from [[Africa]] in the [[1414|twelfth year of Yongle (1414)]]; the Chinese associated the giraffe with the mythical [[qilin]].]] |

|||

[[Image:Information_icon.svg|left]]Hello, this is a message from [[User:CSDWarnBot|an automated bot]]. A tag has been placed on [[:Seed7]], by {{#ifeq:{{{nom}}}|1|[[User:{{{nominator}}}|{{{nominator}}}]] ([[User talk:{{{nominator}}}|talk]] '''·''' [[Special:Contributions/{{{nominator}}}|contribs]]),}} another Wikipedia user, requesting that it be [[Wikipedia:Speedy deletions|speedily deleted]] from Wikipedia. The tag claims that it should be speedily deleted because [[:Seed7]] was previously deleted as a result of an [[Wikipedia:Articles for deletion|articles for deletion]] (or another [[Wikipedia:Deletion policy#Deletion discussion|XfD]])<br><br>To contest the tagging and request that administrators wait before possibly deleting [[:Seed7]], please affix the template <nowiki>{{hangon}}</nowiki> to the page, and put a note on its talk page. If the article has already been deleted, see the advice and instructions at [[WP:WMD]]. Feel free to contact the [[User:CSDWarnBot|bot operator]] if you have any questions about this or any problems with this bot, bearing in mind that '''this bot is only informing you of the nomination for speedy deletion; it does not perform any nominations or deletions itself. To see the user who deleted the page, click [http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Log&page={{urlencode:Seed7}} here]''' [[User:CSDWarnBot|CSDWarnBot]] ([[User talk:CSDWarnBot|talk]]) 07:10, 15 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

Beginning in 1405, the Yongle Emperor entrusted his favored eunuch commander [[Zheng He]] (1371–1433) as the naval admiral for a gigantic new fleet of ships designated for international tributary missions. The Chinese had [[Foreign relations of Imperial China|sent diplomatic missions]] over land and west since the [[Han Dynasty]] (202 BCE–220 CE) and had been engaged in [[Economy of the Song Dynasty|private overseas trade]] leading all the way to [[Chinese exploration|East Africa for centuries]]—culminating in the Song and Yuan dynasties—but no government-sponsored tributary mission of this grandeur and size had ever been assembled before. To service seven different tributary missions abroad, the Nanjing shipyards constructed two thousand vessels from 1403 to 1419, which included the large [[treasure ship]]s that measured 112 m (370 ft) to 134 m (440 ft) in length and 45 m (150 ft) to 54 m (180 ft) in width.<ref name="fairbank 137">Fairbank, 137.</ref> The first voyage from 1405 to 1407 contained 317 vessels with a staff of 70 eunuchs, 180 medical personnel, 5 astrologers, and 300 military officers commanding a total estimated force of 26,800 men.<ref>Fairbank, 137–138.</ref> |

|||

The enormous tributary missions were discontinued after the death of Zheng He, yet his death was only one of many culminating factors which brought the missions to an end. Yongle had [[Fourth Chinese domination (History of Vietnam)|conquered Vietnam]] in 1407, but Ming troops were pushed out in 1428 with significant costs to the Ming treasury; in 1431 the new [[Lê Dynasty]] of Vietnam was recognized as an independent tribute state.<ref name = "fairbank 138"/> There was also the threat and revival of Mongol power on the northern steppe which drew court attention away from other matters; to face this threat, a massive amount of funds were used to build the [[Great Wall of China|Great Wall]] after 1474.<ref name="fairbank 139">Fairbank, 139.</ref> Yongle's moving of the capital from Nanjing to Beijing was largely in response to the court's need of keeping a closer eye on the Mongol threat in the north.<ref>Robinson (1999), 80.</ref> Scholar-officials also associated the lavish expense of the fleets with eunuch power at court, and so halted funding for these ventures as a means to curtail further eunuch influence.<ref>Fairbank, 138–139.</ref> |

|||

== Nomination of [[The Car & Bike Show]] for speedy deletion == |

|||

===Tumu Crisis and the Ming Mongols=== |

|||

Hi! Thanks for your efforts in cleaning up Wikipedia - much appreciated. However, I haven't deleted [[The Car & Bike Show]], as it isn't a candidate for speedy deletion. The reason is that it does give an indication of notability, albeit a very small, unreferenced amount. I don't believe that the article should exist as it stands, but I can't delete it through the speedy deletion process. I would suggest you [[WP:PROD|PROD]] it or go through the [[WP:AFD|AFD]] process. If you have any questions, please drop me a line on my talk page. [[User:StephenBuxton|StephenBuxton]] ([[User talk:StephenBuxton|talk]]) 12:02, 15 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

{{main|Tumu Crisis|Rebellion of Cao Qin}} |

|||

The [[Oirats|Oirat]] Mongol leader [[Esen Tayisi]] launched an invasion into Ming China in July of 1449. The chief eunuch [[Wang Zhen (eunuch)|Wang Zhen]] encouraged [[Zhengtong Emperor|Emperor Zhengtong]] (r. 1435–1449) to personally lead a force to face the Mongols after a recent Ming defeat; marching off with 50,000 troops, Zhengtong left the capital and put his half-brother [[Zhu Qiyu]] in charge of affairs as temporary regent. In the battle that ensued on September 8, his force of 50,000 troops were decimated by Esen's army and Zhengtong was captured and held in captivity by the Mongols—an event known as the [[Tumu Crisis]].<ref name="ebrey east asia 273">Ebrey (2006), 273.</ref> After Zhengtong's capture, Esen's forces plundered their way across the countryside and all the way to the suburbs of Beijing.<ref>Robinson (2000), 533–534.</ref> Following this was another plundering of the Beijing suburbs in November of that year by local bandits and Ming Dynasty soldiers of Mongol descent who dressed as invading Mongols.<ref>Robinson (2000), 534.</ref> Many Han Chinese also took to brigandage soon after the Tumu incident.<ref>''Yingzong Shilu'', 184.17b, 185.5b.</ref><ref>Robinson (1999), 85, footnote 18.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Chemin de ronde muraille long.JPG|thumb|left|200px|The [[Great Wall of China]]; although the [[rammed earth]] walls of the ancient [[Warring States]] were combined into a unified wall under the [[Qin Dynasty|Qin]] and [[Han Dynasty|Han]] dynasties, the vast majority of the brick and stone Great Wall as it is seen today is a product of the Ming Dynasty.]] |

|||

{{talkback|StephenBuxton}} |

|||

The Mongols held the Zhengtong Emperor for ransom. However, this scheme was foiled once Zhengtong's younger brother assumed the throne as the [[Jingtai Emperor]] (r. 1449–1457); the Mongols were also repelled once Jingtai's confidant and defense minister [[Yu Qian]] (1398–1457) gained control of the Ming armed forces. Holding Zhengtong in captivity was a useless bargaining chip for the Mongols as long as another sat on his throne, so they released him back into Ming China.<ref name="ebrey east asia 273"/> Zhengtong was placed under house arrest in the palace until the coup against Jingtai in 1457 known as the "Wresting the Gate Incident".<ref name="robinson 1999 83">Robinson (1999), 83.</ref> Zhengtong retook the throne as the Tianshun Emperor (r. 1457–1464). |

|||

Tianshun's reign was a troubled one and Mongol forces within the Ming military structure continued to be problematic. On August 7, 1461, the Chinese general Cao Qin and his Ming troops of Mongol descent [[Rebellion of Cao Qin|staged a coup against Tianshun]] out of fear of being next on his purge-list of those who aided Jingtai's succession.<ref>Robinson (1999), 84–85.</ref> Mongols serving the Ming military also became increasingly circumspect as the Chinese began to heavily distrust their Mongol subjects after the Tumu Crisis.<ref>Robinson (1999), 96–97.</ref> Cao's rebel force managed to set fire to the western and eastern gates of the [[Imperial City (Beijing)|Imperial City]] (doused by rain during the battle) and killed several leading ministers before his forces were finally cornered and he was forced to commit suicide.<ref>Robinson (1999), 79, 103–108.</ref><ref>Robinson (1999), 108.</ref> |

|||

== Small suggestion == |

|||

The Mongol threat to China was at its greatest level in the 15th century, although periodic raiding continued throughout the dynasty. Like in the Tumu Crisis, the Mongol leader [[Altan Khan]] (1507–1582) invaded China and raided as far as the outskirts of Beijing.<ref name="robinson 1999 81">Robinson (1999), 81.</ref><ref>Laird, 141.</ref> Interestingly enough, the Ming employed troops of Mongol descent to fight back Altan Khan's invasion, as well as Mongol military officers against Cao Qin's abortive coup.<ref>Robinson (1999), 83, 101.</ref> The Mongol incursions prompted the Ming authorities to construct the Great Wall from the late 15th century to the 16th century; John Fairbank notes that "it proved to be a futile military gesture but vividly expressed China's siege mentality."<ref name="fairbank 139"/> Yet the Great Wall was not meant to be a purely defensive fortification; its towers functioned rather as a series of lit beacons and signalling stations to allow rapid warning to friendly units of advancing enemy troops.<ref>Ebrey (1999), 208.</ref> |

|||

Hi, in reference to your [[Link flooding]] article, a small suggestion - instead of saving changes to the article several times in a row with very minor changes, consider using the preview button to tweak your editing until you like it, and then save it. Helps save clutter in the history, and if someone else is editing as well, helps cut down on edit conflicts. [[User:Unforgiven24|Unforgiven24]] ([[User talk:Unforgiven24|talk]]) 13:57, 19 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

=== Isolation to globalization === |

|||

== SpyScan == |

|||

====Illegal trade, piracy, and war with Japan==== |

|||

[[Image:Wokou.jpg|thumb|200px|16th century [[Wokou|Japanese]] pirate raids.]] |

|||

{{see|Qi Jiguang}} |

|||

In 1479, the vice president of the Ministry of War burned the court records documenting Zheng He's voyages; it was one of many events signalling China's shift to an inward foreign policy.<ref name="fairbank 138">Fairbank, 138.</ref> Shipbuilding laws were implemented that restricted vessels to a small size; the concurrent decline of the Ming navy allowed the growth of piracy along China's coasts.<ref name="fairbank 139"/> Japanese pirates—or [[wokou]]—began staging raids on Chinese ships and coastal communities, although much of the piracy was carried out by native Chinese.<ref name="fairbank 139"/> |

|||

Instead of mounting a counterattack, Ming authorities chose to shut down coastal facilities and starve the pirates out; all foreign trade was to be conducted by the state under the guise of formal tribute missions.<ref name="fairbank 139"/> These policies were known as the [[hai jin]] laws, which enacted a strict ban on private maritime activity until the laws' formal abolishment in 1567.<ref name="fairbank 138"/> In this period government-managed overseas trade with [[Japan]] was carried out exclusively at the seaport of [[Ningbo]], trade with the [[Philippines]] exclusively at [[Fuzhou]], and trade with [[Indonesia]] exclusively at [[Guangzhou]].<ref name="ebrey cambridge 211"/> Even then the Japanese were only allowed into port once every ten years and were allowed to bring a maximum of three hundred men on two ships; these laws encouraged many Chinese merchants to engage in widespread illegal trade and smuggling.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 211"/> |

|||

This page is not a speedyable page, hence why I PRODed it; if you read the tag itself it is for pages that read as adverts; things aren't worthy of being CSDed like that just because they are about a product. [[User:Ironholds|<b style="color:#D3D3D3">Ir</b><b style="color:#A9A9A9">on</b><b style="color:#808080">ho</b>]][[User talk:Ironholds|<b style="color:#696969">ld</b><b style="color:#000">s</b>]] 14:47, 19 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

:However, then how do you get the page deleted, because it has or is: |

|||

* no references |

|||

* sounds like advertising |

|||

* is not notable |

|||

* about a rouge spyware app that is spyware |

|||

* written like vandalism |

|||

Seeking your opinion on this. [[User:Tohd8BohaithuGh1|Tohd8BohaithuGh1]] ([[User talk:Tohd8BohaithuGh1#top|talk]]) 14:52, 19 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

:A PROD is a proposed deletion; it gets deleted in 7 days if nobody has a problem with that; if they do, it's sent to AfD and gets deleted that way. In reply to your points: |

|||

The low point in relations between Ming China and Japan occurred during the rule of the great Japanese warlord [[Hideyoshi]], who in 1592 announced he was going to conquer China. In two campaigns that are known collectively as the [[Imjin War]], the Japanese fought with the Korean and Ming armies. Both sides won victories in the war but with Hideyoshi's death in 1598, the Japanese gave up their last Korean bases and returned to Japan. Despite this and the great leadership of Koreans such as the admiral [[Yi Sun-sin]], the Ming generals took credit for the victory. However, the victory came at an enormous cost to the Ming government's treasury: some 26,000,000 ounces of silver.<ref name="ebrey cambridge 214">Ebrey (1999), 214.</ref> |

|||

*Lack of references do not make something deletion-worth |

|||

*It's written nothing like advertising; does calling something "spyware" sound like good advertising to you? personally i'd fire my agent. |

|||

*lack of notability, fine, but it is not "non-notable" within a CSD criteria. You can CSD things if they are non notable people, bands, webcontent or companies/clubs, but for other things it gets more complex and you should take it to PROD or AfD. In addition, you didn't tag it as non-notable you tagged it as advertising, something it clearly is not. |

|||

*yes, it's about spyware; I fail to see how that makes it deletion-worthy |

|||

*It isn't/wasn't written like vandalism, just badly formatted. |

|||

====Trade and contact with Europe==== |

|||

I've replied to your contribution to the Meaburn Staniland AfD, by the way. [[User:Ironholds|<b style="color:#D3D3D3">Ir</b><b style="color:#A9A9A9">on</b><b style="color:#808080">ho</b>]][[User talk:Ironholds|<b style="color:#696969">ld</b><b style="color:#000">s</b>]] 13:31, 20 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||

[[Image:Ming foreign relations 1580.jpg|thumb|right|210px|Military command centers in 1580, concentrated mostly along the seacoast, the northern border, and the southwest; major courier routes shown are based on a map from Timothy Brook's ''The Confusions of Pleasure''.]] |

|||

==[[Imam Mohamud Imam Cumar]]== |

|||

Although [[Jorge Álvares]] was the first to land on Lintin Island in the [[Pearl River Delta]] in May of 1513, it was [[Rafael Perestrello]]—a cousin of the famed [[Christopher Columbus]]—who became the first European explorer to land on the southern coast of mainland China and trade in [[Guangzhou]] in 1516, commanding a [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] vessel with a crew from a Malaysian junk that had sailed from [[Malacca]].<ref name="brook 124"/><ref name="pfoundes 89">Pfoundes, 89.</ref><ref>Nowell, 8.</ref> The Portuguese sent a large subsequent expedition in 1517 to enter port at Guangzhou and open formal trade relations with Chinese authorities.<ref name="brook 124">Brook, 124.</ref> During this expedition the Portuguese attempted to send an inland delegation in the name of [[Manuel I of Portugal]] to the court of the Ming emperor Zhengde; instead the diplomatic mission languished in a Chinese jail and died there.<ref name="brook 124"/> After the death of Zhengde in April 1521, the conservative faction at court that was against expanding commercial relations ordered that the [[Portuguese Malacca|Portuguese conquest of Malacca]]—a loyal vassal to the Ming—was grounds enough to reject the Portuguese embassy.<ref name="cambridge 339">Mote et al., 339.</ref> Simão de Andrade, brother to ambassador [[Fernão Pires de Andrade]], had also stirred Chinese speculation that the Portuguese were kidnapping Chinese children to eat them; Simão had purchased kidnapped children as slaves who were later found in [[Diu]], [[India]].<ref name="mote cambridge 337 338">Mote et al., 337–338.</ref> In 1521, Ming Dynasty naval forces fought and repulsed Portuguese ships at [[Tuen Mun]], where some of the first [[breech-loading weapon|breech-loading]] culverins were introduced to China.<ref>Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 369.</ref> Despite initial hostilities, by 1549 the Portuguese were sending annual trade missions to [[Shangchuan Island]].<ref name="brook 124"/> In 1557 the Portuguese managed to convince the Ming court to agree on a legal port treaty that would establish [[Macau]] as an official Portuguese trade colony on the coasts of the [[South China Sea]].<ref name="brook 124"/> The Portuguese friar [[Gaspar da Cruz]] (c. 1520 – February 5, 1570) traveled to Guangzhou in 1556 and wrote the first complete book on China and the Ming Dynasty that was published in Europe (fifteen days after his death); it included information on its geography, provinces, royalty, official class, bureaucracy, shipping, architecture, farming, craftsmanship, merchant affairs, clothing, religious and social customs, music and instruments, writing, education, and justice.<ref name="dictionary of ming biography">The Ming Biographical History Project of the Association for Asian Studies, 410–411.</ref> |

|||

Hello |

|||

i am the writer of the article Imam Mohamud imam cumar and u sent me a letter that says the article will be deleted. |

|||

please i would like to expand as soon as possible. |

|||

thanks.--[[User:Abgaaloow|Abgaaloow]] ([[User talk:Abgaaloow|talk]]) 15:50, 19 August 2008 (UTC) |

|||