Om: Difference between revisions

Tag: Reverted |

Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 219: | Line 219: | ||

{{Quote| |

{{Quote| |

||

"Of this universe, I am the Father; I am also the Mother, the Sustainer, and the Grandsire. I am the purifier, the goal of knowledge, the '''sacred syllable ''Om'''''. I am the Ṛig Veda, Sāma Veda, and the Yajur Veda." |

" Of this universe, I am the Father; I am also the Mother, the Sustainer, and the Grandsire. I am the purifier, the goal of knowledge, the '''sacred syllable ''Om'''''. I am the Ṛig Veda, Sāma Veda, and the Yajur Veda." |

||

|[[Krishna]] to [[Arjuna]], Bhagavad Gita 9.17|<ref>https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/9/verse/16-17</ref><ref name=jfowler164>Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, {{ISBN|978-1845193461}}, page 164</ref>}} |

|[[Krishna]] to [[Arjuna]], Bhagavad Gita 9.17|<ref>https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/9/verse/16-17</ref><ref name=jfowler164>Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, {{ISBN|978-1845193461}}, page 164</ref>}} |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

{{Quote| |

{{Quote| |

||

"Therefore, uttering '''Om''', the acts of [[yagna]] (fire ritual), [[dāna]] (charity) and [[Tapas (Sanskrit)|tapas]] (austerity) as enjoined in the scriptures, are always begun by those who study the [[Brahman]]." |

" Therefore, uttering '''Om''', the acts of [[yagna]] (fire ritual), [[dāna]] (charity) and [[Tapas (Sanskrit)|tapas]] (austerity) as enjoined in the scriptures, are always begun by those who study the [[Brahman]]." |

||

|Bhagavad Gita 17.24|<ref name=jfowler271>Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), ''The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students'', Sussex Academic Press, {{ISBN|978-1845193461}}, page 271</ref><ref>Translator: KT Telang, Editor: [[Max Muller]], {{Google books|5cPKAgAAQBAJ|The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita}}, Routledge Print, {{ISBN|978-0700715473}}, page 120</ref>}} |

|Bhagavad Gita 17.24|<ref name=jfowler271>Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), ''The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students'', Sussex Academic Press, {{ISBN|978-1845193461}}, page 271</ref><ref>Translator: KT Telang, Editor: [[Max Muller]], {{Google books|5cPKAgAAQBAJ|The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita}}, Routledge Print, {{ISBN|978-0700715473}}, page 120</ref>}} |

||

Revision as of 08:53, 14 September 2021

Om or Aum (; ॐ, ओ३म्, IAST: Ōṃ , Tamil: ௐ, ஓம்) is the sound of a sacred spiritual symbol in Indian religions, mainly in Hinduism. It signifies the essence of the ultimate reality, consciousness or Atman.[1][2][3] More broadly, it is a syllable that is chanted either independently or before a spiritual recitation in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.[4][5] The meaning and connotations of Om vary between the diverse schools within and across the various traditions. It is also part of the iconography found in ancient and medieval era manuscripts, temples, monasteries and spiritual retreats in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.[6][7]

In Hinduism, Om is one of the most important spiritual symbols.[8][9] It refers to Atman (soul, self within) and Brahman (ultimate reality, entirety of the universe, truth, divine, supreme spirit, cosmic principles, knowledge).[10][11][12] The syllable is often found at the beginning and the end of chapters in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts.[12] It is a sacred spiritual incantation made before and during the recitation of spiritual texts, during puja and private prayers, in ceremonies of rites of passage (sanskara) such as weddings, and sometimes during meditative and spiritual activities such as Yoga.[13][14]

The syllable Om is also referred to as Onkara/Omkara (ओङ्कार, oṅkāra), omkara (ओंकार, oṃkāra) and pranav/pranava (प्रणव, praṇava).[15][16]

Common names and synonyms

The syllable Om (Devanagari: ॐ, Kannada: ಓಂ, Tamil: ௐ, Malayalam: ഓം, Telugu: ఓం, Bengali: ওঁ, Odia: ଓଁ or ଓଁ, Tibetan: ༀ) is referred to as praṇava.[17][18] Other used terms are akṣara (literally, letter of the alphabet, imperishable, immutable) or ekākṣara (one letter of the alphabet) and omkāra (meaning literally "Om-maker" denoting the first source of the sound "Om" and connoting the act of creation).[19][20][21][22] Udgītha (उद्गीथ; song, chant), a word found in Samaveda and bhasya (commentaries) based on it, is also used as a name of the syllable.[23] As o is the guṇa vowel grade of u, the word om can be considered to consist of three phonemes: "ā-u-m",[24][25][26][27] though it is often described as trisyllabic despite this being either archaic or the result of translation.

Origin and meaning

The etymological origins of ōm/āum have long been discussed and disputed, with even the Upanishads having proposed multiple Sanskrit etymologies for āum, including: from "ām" (आम्; "yes"), from "ávam" (आवम्; "that, thus, yes"), and from the Sanskrit roots "āv-" (अव्; "to urge") or "āp-" (आप्; "to attain"). [note 1][28] In 1889, Maurice Blumfield proposed an origin from a Proto-Indo-European introductory particle "*au" with a function similar to the Sanskrit particle "atha" (अथ).[28] However, contemporary Indologist Asko Parpola proposes a borrowing from Dravidian "*ām" meaning "'it is so', 'let it be so', 'yes'", a contraction of "*ākum", cognate with modern Tamil "ām" (ஆம்) meaning "yes".[28][29]

Regardless of its original meaning, the syllable Om evolves to mean many abstract ideas even in the earliest Upanishads. Max Müller and other scholars state that these philosophical texts recommend Om as a "tool for meditation", explain various meanings that the syllable may be in the mind of one meditating, ranging from "artificial and senseless" to "highest concepts such as the cause of the Universe, essence of life, Brahman, Atman, and Self-knowledge".[30][31]

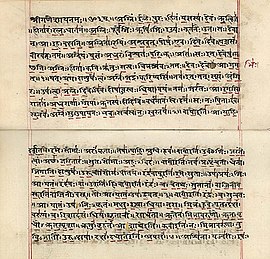

The syllable Om is first mentioned in the Upanishads, the mystical texts associated with the Vedanta philosophy. It has variously been associated with concepts of "cosmic sound" or "mystical syllable" or "affirmation to something divine", or as symbolism for abstract spiritual concepts in the Upanishads.[12] In the Aranyaka and the Brahmana layers of Vedic texts, the syllable is so widespread and linked to knowledge, that it stands for the "whole of Veda".[12] The symbolic foundations of Om are repeatedly discussed in the oldest layers of the early Upanishads.[32][33] The Aitareya Brahmana of Rig Veda, in section 5.32, for example suggests that the three phonetic components of Oṃ (a + u + ṃ) correspond to the three stages of cosmic creation, and when it is read or said, it celebrates the creative powers of the universe.[12][34] The Brahmana layer of Vedic texts equate Om with Bhur-bhuvah-Svah, the latter symbolizing "the whole Veda". They offer various shades of meaning to Om, such as it being "the universe beyond the sun", or that which is "mysterious and inexhaustible", or "the infinite language, the infinite knowledge", or "essence of breath, life, everything that exists", or that "with which one is liberated".[12] The Samaveda, the poetical Veda, orthographically maps Om to the audible, the musical truths in its numerous variations (Oum, Aum, Ovā Ovā Ovā Um, etc.) and then attempts to extract musical meters from it.[12]

Written representation

South Asia

Phonologically, the syllable ओम् represents /aum/, which is regularly monophthongised to [õː] in Sanskrit phonology. When occurring within spoken Sanskrit, the syllable is subject to the normal rules of sandhi in Sanskrit grammar, however with the additional peculiarity that after preceding a or ā, the au of aum does not form vriddhi (au) but guna (o) per Pāṇini 6.1.95 (i.e. 'om').

It is sometimes also written ओ३म् (ō̄m [oːːm]), notably by Arya Samaj, where ३ (i.e., the digit "3") is pluta ("three times as long"), indicating a length of three morae (that is, the time it takes to say three syllables) — an overlong nasalised close-mid back rounded vowel.

The Om symbol, ॐ, is a ligature in Devanagari, combining ओ (au) and chandrabindu (ँ, ṃ). In Unicode, the symbol is encoded at U+0950 ॐ DEVANAGARI OM and at U+1F549 🕉 OM SYMBOL ("generic symbol independent of Devanagari font").

The Om or Aum symbol is found on ancient coins, in regional scripts. In Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura era coins (dated from the 1st to 4th centuries) are embossed with Aum along with other symbols.[35] Nagari or Devanagari representations are found epigraphically on medieval sculpture, such as the dancing Shiva (ca. 10th to 12th century); Joseph Campbell (1949) even argued that the dance posture itself can be taken to represent Om as a symbol of the entirety of "consciousness, universe" and "the message that God is within a person and without".[36]

East and Southeast Asia

The Om symbol, with epigraphical variations, is also found in many Southeast Asian countries.

In Cambodia, the symbol is known as Om, Aom, or Unalaom. In Khmer literature, the symbol is called Komutr (Khmer: គោមូត្រ). The Khmer adopted the symbol since the 1st century during the Kingdom of Funan as seen on artifacts from Angkor Borei, once the capital of Funan. The symbol is seen on numerous Khmer statues from Chenla to Khmer Empire periods and still in used until the present day. This Khmer version of Om symbol is popularly used in Khmer sacred tattoos known as Sak Yant and Khmer Buddhist texts and literatures.[37][38] The Cambodian official seal has similarly incorporated the Aum symbol.[39]

It is also called Unalom or Aum in Thailand and has been a part of various flags and official emblems such as in the Thong Chom Klao of King Rama IV (r. 1851–1868).[40]

In traditional Chinese characters, it is written as 唵 (pinyin: ǎn), and as 嗡 (pinyin: wēng) in simplified Chinese characters.[citation needed]

There have been proposals that the Om syllable may already have had written representations in Brahmi script, dating to before the Common Era. A proposal by Deb (1848) held that the swastika is "a monogrammatic representation of the syllable Om, wherein two Brahmi /o/ characters (U+11011 𑀑 BRAHMI LETTER O) were superposed crosswise and the 'm' was represented by dot".[41] A commentary in Nature considers this theory questionable and unproven.[42] Roy (2011) proposed that Om was represented using the Brahmi symbols for "A", "U" and "M" (𑀅𑀉𑀫), and that this may have influenced the unusual epigraphical features of the symbol ॐ for Om.[43][44]

Representation in various scripts

Northern Brahmic

Southern Brahmic

East Asian

Hinduism

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

It is the most sacred syllable symbol and mantra of Brahman, the highest Universal Principle, the Ultimate Reality.[45] Om connotes the metaphysical concept of Brahman. The syllable is often chanted either independently or before a mantra;[46][4][5] it signifies the Brahman as the ultimate reality, consciousness or Atma.[1][2][3] The Om sound is the primordial sound and is called the Shabda-Brahman (Brahman as sound).[47] In Hinduism, Om is one of the most important spiritual sounds.[8][9]

Om refers to Atman (soul, self within) and Brahman (ultimate reality, entirety of the universe, truth, divine, supreme spirit, cosmic principles, knowledge).[10][11][12] The syllable is often found at the beginning and the end of chapters in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts.[12] It is a sacred spiritual incantation made before and during the recitation of spiritual texts, during puja and private prayers, in ceremonies of rites of passages (sanskara) such as weddings, and sometimes during meditative and spiritual activities such as Yoga.[13][14]

Om came to be used as a standard utterance at the beginning of mantras, chants or citations taken from the Vedas. For example, the Gayatri mantra, which consists of a verse from the Rigveda Samhita (RV 3.62.10), is prefixed not just by Om but by Om followed by the formula bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ.[48] Such recitations continue to be in use in Hinduism, with many major incantations and ceremonial functions beginning and ending with Om.[5]

Upanishads

The syllable Om is described with various meanings in the Upanishads. Descriptions include "the sacred sound, the Yes!, the Vedas, the Udgitha (song of the universe), the infinite, the all encompassing, the whole world, the truth, the ultimate reality, the finest essence, the cause of the Universe, the essence of life, the Brahman, the Atman, the vehicle of deepest knowledge, and Self-knowledge".[31]

Chandogya Upanishad

The Chandogya Upanishad is one of the oldest Upanishads of Hinduism. It opens with the recommendation that "let a man meditate on Om".[49] It calls the syllable Om as udgitha (उद्गीथ; song, chant), and asserts that the significance of the syllable is thus: the essence of all beings is earth, the essence of earth is water, the essence of water are the plants, the essence of plants is man, the essence of man is speech, the essence of speech is the Rig Veda, the essence of the Rig Veda is the Sama Veda, and the essence of Sama Veda is the udgitha (song, Om).[50]

Rik (ऋच्, Ṛc) is speech, states the text, and Sāman (सामन्) is breath; they are pairs, and because they have love for each other, speech and breath find themselves together and mate to produce a song.[49][50] The highest song is Om, asserts section 1.1 of Chandogya Upanishad. It is the symbol of awe, of reverence, of threefold knowledge because Adhvaryu invokes it, the Hotr recites it, and Udgatr sings it.[50][51]

The second volume of the first chapter continues its discussion of syllable Om, explaining its use as a struggle between Devas (gods) and Asuras (demons).[52] Max Muller states that this struggle between gods and demons is considered allegorical by ancient Indian scholars, as good and evil inclinations within man, respectively.[53] The legend in section 1.2 of Chandogya Upanishad states that gods took the Udgitha (song of Om) unto themselves, thinking, "with this song we shall overcome the demons".[54] The syllable Om is thus implied as that which inspires the good inclinations within each person.[53][54]

Chandogya Upanishad's exposition of syllable Om in its opening chapter combines etymological speculations, symbolism, metric structure and philosophical themes.[51][55] In the second chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad, the meaning and significance of Om evolves into a philosophical discourse, such as in section 2.10 where Om is linked to the Highest Self,[56] and section 2.23 where the text asserts Om is the essence of three forms of knowledge, Om is Brahman and "Om is all this [observed world]".[57]

Katha Upanishad

The Katha Upanishad is the legendary story of a little boy, Nachiketa – the son of sage Vajasravasa – who meets Yama, the vedic deity of death. Their conversation evolves to a discussion of the nature of man, knowledge, Atman (Soul, Self) and moksha (liberation).[58] In section 1.2, Katha Upanishad characterizes Knowledge/Wisdom as the pursuit of good, and Ignorance/Delusion as the pursuit of pleasant,[59] that the essence of Veda is to make man liberated and free, look past what has happened and what has not happened, free from the past and the future, beyond good and evil, and one word for this essence is the word Om.[60]

The word which all the Vedas proclaim,

That which is expressed in every Tapas (penance, austerity, meditation),

That for which they live the life of a Brahmacharin,

Understand that word in its essence: Om! that is the word.

Yes, this syllable is Brahman,

This syllable is the highest.

He who knows that syllable,

Whatever he desires, is his.— Katha Upanishad, 1.2.15-1.2.16[60]

Maitri Upanishad

The Maitrayaniya Upanishad in sixth Prapathakas (lesson) discusses the meaning and significance of Om. The text asserts that Om represents Brahman-Atman. The three roots of the syllable, states the Maitri Upanishad, are A + U + M.[61] The sound is the body of Soul, and it repeatedly manifests in three: as gender-endowed body – feminine, masculine, neuter; as light-endowed body – Agni, Vayu and Aditya; as deity-endowed body – Brahma, Rudra[am] and Vishnu; as mouth-endowed body – Garhapatya, Dakshinagni and Ahavaniya;[62] as knowledge-endowed body – Rig, Saman and Yajur;[63] as world-endowed body – Bhūr, Bhuvaḥ and Svaḥ; as time-endowed body – Past, Present and Future; as heat-endowed body – Breath, Fire and Sun; as growth-endowed body – Food, Water and Moon; as thought-endowed body – intellect, mind and psyche.[61][64] Brahman exists in two forms – the material form, and the immaterial formless.[65] The material form is changing, unreal. The immaterial formless isn't changing, real. The immortal formless is truth, the truth is the Brahman, the Brahman is the light, the light is the Sun which is the syllable Om as the Self.[66][67]

The world is Om, its light is Sun, and the Sun is also the light of the syllable Om, asserts the Upanishad. Meditating on Om, is acknowledging and meditating on the Brahman-Atman (Soul, Self).[61]

Mundaka Upanishad

The Mundaka Upanishad in the second Mundakam (part), suggests the means of knowing the Self(Atman) and the Brahman to be meditation, self-reflection and introspection, that can be aided by the symbol Om.[68][69]

That which is flaming, which is subtler than the subtle,

on which the worlds are set, and their inhabitants –

That is the indestructible Brahman.[70]

It is life, it is speech, it is mind. That is the real. It is immortal.

It is a mark to be penetrated. Penetrate It, my friend.

Taking as a bow the great weapon of the Upanishad,

one should put upon it an arrow sharpened by meditation,

Stretching it with a thought directed to the essence of That,

Penetrate[71] that Imperishable as the mark, my friend.

Om is the bow, the arrow is the Self(Atman), Brahman the mark,

By the undistracted man is It to be penetrated,

One should come to be in It,

as the arrow becomes one with the mark.

Adi Shankara, in his review of the Mundaka Upanishad, states Om as a symbolism for Atman (soul, self).[74]

Mandukya Upanishad

The Mandukya Upanishad opens by declaring, "Om!, this syllable is this whole world".[75] Thereafter it presents various explanations and theories on what it means and signifies.[76] This discussion is built on a structure of "four fourths" or "fourfold", derived from A + U + M + "silence" (or without an element).[75][76]

- Aum as all states of Kala

- In verse 1, the Upanishad states that time is threefold: the past, the present and the future, that these three are "Aum". The four fourth of time is that which transcends time, that too is "Aum" expressed.[76]

- Aum as all states of Atman

- In verse 2, states the Upanishad, everything is Brahman, but Brahman is Atman (the Soul, Self), and that the Atman is fourfold.[75] Johnston summarizes these four states of Self, respectively, as seeking the physical, seeking inner thought, seeking the causes and spiritual consciousness, and the fourth state is realizing oneness with the Self, the Eternal.[77]

- Aum as all states of consciousness

- In verses 3 to 6, the Mandukya Upanishad enumerates four states of consciousness: wakeful, dream, deep sleep and the state of ekatma (being one with Self, the oneness of Self).[76] These four are A + U + M + "without an element" respectively.[76]

- Aum as all of knowledge

- In verses 9 to 12, the Mandukya Upanishad enumerates fourfold etymological roots of the syllable "Aum". It states that the first element of "Aum" is A, which is from Apti (obtaining, reaching) or from Adimatva (being first).[75] The second element is U, which is from Utkarsa (exaltation) or from Ubhayatva (intermediateness).[76] The third element is M, from Miti (erecting, constructing) or from Mi Minati, or apīti (annihilation).[75] The fourth is without an element, without development, beyond the expanse of universe. In this way, states the Upanishad, the syllable Om is indeed the Atman (the self).[75][76]

Shvetashvatara Upanishad

The Shvetashvatara Upanishad, in verses 1.14 to 1.16, suggests meditating with the help of syllable Om, where one's perishable body is like one fuel-stick and the syllable Om is the second fuel-stick, which with discipline and diligent rubbing of the sticks unleashes the concealed fire of thought and awareness within. Such knowledge, asserts the Upanishad, is the goal of Upanishads.[78][79] The text asserts that Om is a tool of meditation empowering one to know the God within oneself, to realize one's Atman (Soul, Self).[80]

Ganapati Upanishad

The Ganapati Upanishad asserts that Ganesha is same as Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, all deities, the universe, and Om.[83]

(O Lord Ganapati!) You are (the Trimurti) Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesa. You are Indra. You are fire [Agni] and air [Vāyu]. You are the sun [Sūrya] and the moon [Chandrama]. You are Brahman. You are (the three worlds) Bhuloka [earth], Antariksha-loka [space], and Swargaloka [heaven]. You are Om. (That is to say, You are all this).

— Gaṇapatya Atharvaśīrṣa 6, [84]

Aranyakas

Aitareya Aranyaka

Aitareya Aranyaka in verse 23.6,[clarification needed] explains Om as "an acknowledgment, melodic confirmation, something that gives momentum and energy to a hymn".[8]

Om (ॐ) is the pratigara (agreement) with a hymn. Likewise is tatha (so be it) with a song. But Om is something divine, and tatha is something human.

— Aitareya Aranyaka 23.6, [8]

Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita, in the Epic Mahabharata, mentions the meaning and significance of Om in several verses. According to Jeaneane Fowler, verse 9.17 of the Bhagavad Gita synthesizes the competing dualistic and monist streams of thought in Hinduism, by using "Om which is the symbol for the indescribable, impersonal Brahman".[85]

" Of this universe, I am the Father; I am also the Mother, the Sustainer, and the Grandsire. I am the purifier, the goal of knowledge, the sacred syllable Om. I am the Ṛig Veda, Sāma Veda, and the Yajur Veda."

The significance of the sacred syllable in the Hindu traditions, is similarly highlighted in other verses of the Gita, such as verse 17.24 where the importance of Om during prayers, charity and meditative practices is explained as follows,[87]

" Therefore, uttering Om, the acts of yagna (fire ritual), dāna (charity) and tapas (austerity) as enjoined in the scriptures, are always begun by those who study the Brahman."

Yoga Sutra

The aphoristic verse 1.27 of Pantanjali's Yogasutra links Om to Yoga practice, as follows,[89]

तस्य वाचकः प्रणवः ॥२७॥

His word is Om.

— Yogasutra 1.27, [89]

Johnston states this verse highlights the importance of Om in the meditative practice of Yoga, where it symbolizes three worlds in the Soul; the three times – past, present and future eternity, the three divine powers – creation, preservation and transformation in one Being; and three essences in one Spirit – immortality, omniscience and joy. It is, asserts Johnston, a symbol for the perfected Spiritual Man (his emphasis).[89]

Puranas

The medieval era texts of Hinduism, such as the Puranas adopt and expand the concept of Om in their own ways, and to their own theistic sects. According to the Vayu Purana, Om is the representation of the Hindu Trimurti, and represents the union of the three gods, viz. A for Brahma, U for Vishnu and M for Shiva. The three sounds also symbolise the three Vedas, namely (Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda).[citation needed]

In Vaishnava traditions Krishna is revered as Svayam Bhagavan and Om is interpretted accordingly; A is said to represent Bhagavan Krishna (avatar of Vishnu), U represents Srimati Radharani (avatar of Mahalakshmi), and M represents jiva, the soul of the devotee. Accordingly, the Vaishnava Garuda Purana equates the recitation of Om with obeisance to Vishnu.[90][91]

Shaiva traditions

In Shaiva traditions, the Shiva Purana highlights the relation between deity Shiva and the Pranava or Om. Shiva is declared to be Om, and that Om is Shiva.[92]

Shakta traditions

In the thealogy of Shakta traditions, Om connotes the female divine energy, Adi Parashakti, represented in the Tridevi: A for the creative energy (the Shakti of Brahma), Mahasaraswati, U for the preservative energy (the Shakti of Vishnu), Mahalakshmi, and M for the destructive energy (the Shakti of Shiva), Mahakali. The 12th book of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana describes the Goddess as the mother of the Vedas, she the Adya Shakti (primal energy, primordial power), and the essence of the Gayatri mantra.[93][94][95]

Jainism

In Jainism, Om is considered a condensed form of reference to the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi by their initials A+A+A+U+M (o3m).

The Dravyasamgraha quotes a Prakrit line:[96]

- ओम एकाक्षर पञ्चपरमेष्ठिनामादिपम् तत्कथमिति चेत "अरिहंता असरीरा आयरिया तह उवज्झाया मुणियां"[an]

- Translation: AAAUM (or just "Om") is the one syllable short form of the initials of the five supreme beings (Pañca-Parameṣṭhi): "Arihant, Ashiri, Acharya, Upajjhaya, Muni".[97]

By extension, the Om symbol is also used in Jainism to represent the first five lines of the Namokar mantra,[98] the most important part of the daily prayer in the Jain religion, which honours the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi. These five lines are (in English): "(1.) veneration to the Arhats, (2.) veneration to the perfect ones, (3.) veneration to the masters, (4.) veneration to the teachers, (5.) veneration to all the monks in the world".[96]

Buddhism

Om is often used in some later schools of Buddhism, for example Tibetan Buddhism, which was influenced by Indian Hinduism and Tantra.[99][100]

In Chinese Buddhism, Om is often transliterated as the Chinese character 唵 (pinyin ǎn) or 嗡 (pinyin wēng).

Tibetan Buddhism and Vajrayana

In Tibetan Buddhism, Om is often placed at the beginning of mantras and dharanis. Probably the most well known mantra is "Om mani padme hum", the six syllable mantra of the Bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteśvara. This mantra is particularly associated with the four-armed Shadakshari form of Avalokiteśvara. Moreover, as a seed syllable (bija mantra), Aum is considered sacred and holy in Esoteric Buddhism.[101]

Some scholars interpret the first word of the mantra oṃ maṇipadme hūṃ to be auṃ, with a meaning similar to Hinduism – the totality of sound, existence and consciousness.[102][103]

Oṃ has been described by the 14th Dalai Lama as "composed of three pure letters, A, U, and M. These symbolize the impure body, speech, and mind of everyday unenlightened life of a practitioner; they also symbolize the pure exalted body, speech and mind of an enlightened Buddha."[104][105] According to Simpkins, Om is a part of many mantras in Tibetan Buddhism and is a symbolism for "wholeness, perfection and the infinite".[106]

Japanese Buddhism

A-un

The term A-un (阿吽) is the transliteration in Japanese of the two syllables "a" and "hūṃ", written in Devanagari as अहूँ. In Japanese, it is often equated with the syllable Om. The original Sanskrit term is composed of two letters, the first (अ) and the last (ह) letters of the Devanagari abugida, with diacritics (including Anusvara) on the latter indicating the "-ūṃ" of "hūṃ". Together, they symbolically represent the beginning and the end of all things.[107] In Japanese Mikkyō Buddhism, the letters represent the beginning and the end of the universe.[108] This is comparable to Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, similarly adopted by Christianity to symbolize Christ as the beginning and end of all.

The term a-un is used figuratively in some Japanese expressions as "a-un breathing" (阿吽の呼吸, a-un no kokyū) or "a-un relationship" (阿吽の仲, a-un no naka), indicating an inherently harmonious relationship or non-verbal communication.

Niō guardian kings and Komainu lion-dogs

The term is also used in Buddhist architecture and Shinto to describe the paired statues common in Japanese religious settings, most notably the Niō (仁王) and the komainu (狛犬).[107] One (usually on the right) has an open mouth regarded by Buddhists as symbolically speaking the "A" syllable; the other (usually on the left) has a closed mouth, symbolically speaking the "Un" syllable. The two together are regarded as saying "A-un", which is called the vajra-breath. The generic name for statues with an open mouth is agyō (阿形, lit. "a" shape), that for those with a closed mouth ungyō (吽形, lit. "'un' shape").[107]

Niō statues in Japan, and their equivalent in East Asia, appear in pairs in front of Buddhist temple gates and stupas, in the form of two fierce looking guardian kings (Vajrapani).[109][110]

Komainu, also called lion-dogs, found in Japan, Korea and China, also occur in pairs before Buddhist temples and public spaces, and again, one has an open mouth (Agyō), the other closed (Ungyō).[111][112][113]

Sikhism

Ik Onkar, iconically represented as ੴ in Sikhism are the opening words of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh scripture.[114] It is the statement that 'there is one God',[115] and that there is 'singularity despite seeming plurality'.[116] Ik Onkar is a phrase, which is a compound of the numeral one (ik) and onkar, states Doniger, canonically understood in Sikhism to refer to "absolute monotheistic unity of God".[114] Ik Onkar is part of the "Mul Mantra" in Sikh teachings and represents "One God", states Gulati.[117]

Onkar is, states Wazir Singh, a "variation of Om (Aum) of the ancient Indian scriptures (with a change in its orthography), implying the unifying seed-force that evolves as the universe".[118] Guru Nanak wrote a poem entitled Onkar in which, states Doniger, he "attributed the origin and sense of speech to the Divinity, who is thus the Om-maker".[114]

Onkar ('the Primal Sound') created Brahma, Onkar fashioned the consciousness,

From Onkar came mountains and ages, Onkar produced the Vedas,

By the grace of Onkar, people were saved through the divine word,

By the grace of Onkar, they were liberated through the teachings of the Guru.— Ramakali Dakkhani, Adi Granth 929-930, Translated by Pashaura Singh[119]

Ik Aumkara appears at the start of Mul Mantra, states Kohli, and it occurs as "Aum" in the Upanishads and in Gurbani.[120]

According to Pashaura Singh, Onkar is a foundational word (shabad, Mul Mantar), the seed of Sikh scripture, and the basis of the "whole creation of time and space".[119] It is interpreted differently than other Indian religions, and is used frequently as invocation in Sikh scripture, and is central to Sikhism.[119]

Thelema

For both symbolic and numerological reasons, Aleister Crowley adapted aum into a Thelemic magical formula, AUMGN, adding a silent 'g' (as in the word 'gnosis') and a nasal 'n' to the m to form the compound letter 'MGN'; the 'g' makes explicit the silence previously only implied by the terminal 'm' while the 'n' indicates nasal vocalisation connoting the breath of life and together they connote knowledge and generation. Om appears in this extended form throughout Crowley's magical and philosophical writings, notably appearing in his Gnostic Mass. Crowley discusses its symbolism briefly in section F of Liber Samekh and in detail in chapter 7 of Magick (Book 4).[121][122][123][124]

Modern reception

The Brahmic script om-ligature has become widely recognized in Western counterculture since the 1960s, mostly in its standard Devanagari form (ॐ), but the Tibetan alphabet om (ༀ) has also gained limited currency in popular culture.[125]

Notes

- ^ Praṇava Upaniṣad in Gopatha Brāhmaṇa 1.1.26 and Uṇādisūtra 1.141/1.142

- ^ ওঁ (U+0993 & U+0981)

- ^ ॐ (U+0950)

- ^ ૐ (U+0AD0)

- ^ ੴ (U+0A74)

- ^ ꣽ (U+A8FD)

- ^ ᰣᰨᰵ (U+1C23 & U+1C28 & U+1C35)

- ^ ᤀᤥᤱ (U+1900 & U+1925 & U+1931)

- ^ ꫲ (U+AAF2)

- ^ 𑘌𑘽 (U+1160C) & (U+1163D)

- ^ ଓଁ (U+0B13 & U+0B01)

- ^ ଓଁ (U+0B13 & U+200D & U+0B01)

- ^ 𑑉 (U+11449)

- ^ 𑇄 (U+111C4)

- ^ 𑖌𑖼 (U+1158C & U+115BC)

- ^ 𑩐𑩖𑪖 (U+11A50 & U+11A55 & U+11A96)

- ^ 𑚈𑚫 (U+11688) & (U+116AB)

- ^ ༀ (U+0F00)

- ^ 𑓇 (U+114C7

- ^ ᬒᬁ (U+1B12 & U+1B01)

- ^ ဥုံ (U+1025 & U+102F & U+1036)

- ^ 𑄃𑄮𑄀 (U+11103 & U+1112E & U+11100)

- ^ ꨀꨯꨱꩌ (U+AA00 & U+AA2F & U+AA31 & U+AA4C)

- ^ 𑍐 (U+11350)

- ^ ꦎꦴꦀ (U+A98E & U+A980 & U+A9B4)

- ^ ಓಂ (U+0C93 & U+0C82)

- ^ ឱំ (U+17B1 & U+17C6)

- ^ ⁄ (U+17DA)

- ^ ໂອໍ (U+0EAD & U+0EC2 & U+0ECD)

- ^ ഓം (U+0D13 & U+0D02)

- ^ ඕං (U+0D95) & (U+0D82)

- ^ ௐ (U+0BD0)

- ^ ఓం (U+0C13 & U+0C02)

- ^ โอํ (U+0E2D & U+0E42 & U+0E4D)

- ^ ๛ (U+0E5B)

- ^ 唵 (U+5535)

- ^ 옴 (U+110B & U+1169 & U+1106)

- ^ オーム (U+30AA & U+30FC & U+30E0)

- ^ ᢀᠣᠸᠠ (U+1826 & U+1838 & U+1820 & U+1880)

- ^ later called Shiva

- ^ oma ekākṣara pañca-parameṣṭhi-nāmā-dipam tatkathamiti cheta "arihatā asarīrā āyariyā taha uvajjhāyā muṇiyā"

References

- ^ a b James Lochtefeld (2002), "Om", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931804, page 482

- ^ a b Barbara A. Holdrege (1996). Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture. SUNY Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7914-1640-2.

- ^ a b "Om". Merriam-Webster (2013), Pronounced: \ˈōm\

- ^ a b Jan Gonda (1963), The Indian Mantra, Oriens, Vol. 16, pp. 244–297

- ^ a b c Julius Lipner (2010), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415456760, pp. 66–67

- ^ T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993), Elements of Hindu Iconography, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808775, p. 248

- ^ Sehdev Kumar (2001), A Thousand Petalled Lotus: Jain Temples of Rajasthan, ISBN 978-8170173489, p. 5

- ^ a b c d Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus (2011), Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110181593, page 435

- ^ a b Krishna Sivaraman (2008), Hindu Spirituality Vedas Through Vedanta, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812543, page 433

- ^ a b David Leeming (2005), The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195156690, page 54

- ^ a b Hajime Nakamura, A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120819634, page 318

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus (2011), Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110181593, pages 435–456

- ^ a b David White (2011), Yoga in Practice, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691140865, pp. 104–111

- ^ a b Alexander Studholme (2012), The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791453902, pages 1–4

- ^ Nityanand Misra (25 July 2018). The Om Mala: Meanings of the Mystic Sound. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-93-87471-85-6.

- ^ "OM". Sanskrit English Dictionary, University of Köln, Germany

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2002), Pranava, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931804, page 522

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 74-75, 347, 364, 667

- ^ Diana Eck (2013), India: A Sacred Geography, Random House, ISBN 978-0385531924, page 245

- ^ R Mehta (2007), The Call of the Upanishads, Motilal Barnarsidass, ISBN 978-8120807495, page 67

- ^ Omkara, Sanskrit-English Dictionary, University of Koeln, Germany

- ^ CK Chapple, W Sargeant (2009), The Bhagavad Gita, Twenty-fifth–Anniversary Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438428420, page 435

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 12 with footnote 1

- ^ Osho (2012). The Book of Secrets, unpaginated. Osho International Foundation. ISBN 9780880507707.

- ^ Mehta, Kiran K. (2008). Milk, Honey and Grapes, p.14. Puja Publications, Atlanta. ISBN 9781438209159.

- ^ Misra, Nityanand (2018). The Om Mala, unpaginated. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9789387471856.

- ^ Vālmīki; trans. Mitra, Vihārilāla (1891). The Yoga-vásishtha-mahárámáyana of Válmiki, Volume 1, p.61. Bonnerjee and Company. [ISBN unspecified].

- ^ a b c Parpola, Asko (1981). "On the Primary Meaning and Etymology of the Sacred Syllable ōm". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 50: 195–214. ISSN 2323-5209.

- ^ Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism : the Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. New York. ISBN 9780190226909.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 1-21

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 67-85, 227, 284, 308, 318, 361-366, 468, 600-601, 667, 772

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 207

- ^ John Grimes (1995), Ganapati: The Song of Self, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791424391, pages 78-80 and 201 footnote 34

- ^ Aitareya Brahmana 5.32, Rig Veda, pages 139-140 (Sanskrit); for English translation: See Arthur Berriedale Keith (1920). The Aitareya and Kauṣītaki Brāhmaṇas of the Rigveda. Harvard University Press. p. 256.

- ^ Henry Parker, Ancient Ceylon (1909), p. 490.

- ^ Joseph Campbell (1949), The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 108f.

- ^ "ឱម: ប្រភពនៃរូបសញ្ញាឱម". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "ឱម : អំណាចឱមនៅក្នុងសាសនា". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ James Minahan (2009), The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems, ISBN 978-0313344961, pages 28-29

- ^ Deborah Wong (2001), Sounding the Center: History and Aesthetics in Thai Buddhist Performance, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226905853, page 292

- ^ HK Deb, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume XVII, Number 3, page 137

- ^ The Swastika, p. PA365, at Google Books, Nature, Vol. 110, No. 2758, page 365

- ^ Ankita Roy (2011), Rediscovering the Brahmi Script. Industrial Design Center, IIT Bombay. See the section, "Ancient Symbols".

- ^ SC Kak (1990), Indus and Brahmi: Further Connections. Cryptologia, 14(2), pages 169-183

- ^ "Om".

- ^ Ellwood, Robert S.; Alles, Gregory D. (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. pp. 327–328. ISBN 9781438110387.

- ^ Beck, Guy L. (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 42–48. ISBN 9788120812611.

- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1893), Indian Wisdom, Luzac & Co., London, page 17

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 1-3 with footnotes

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 68-70

- ^ a b Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 171-185

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 70-71 with footnotes

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-6 with footnotes

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 178-180

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-19 with footnotes

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 28 with footnote 1

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 35

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 269-273

- ^ Max Muller (1962), Katha Upanishad, in The Upanishads – Part II, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0486209937, page 8

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 284-286

- ^ a b c Max Muller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 307-308

- ^ this is a reference to the three major Vedic fire rituals

- ^ this is a reference to the three major Vedas

- ^ Maitri Upanishad – Sanskrit Text with English Translation[permanent dead link] EB Cowell (Translator), Cambridge University, Bibliotheca Indica, page 258-260

- ^ Max Muller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 306-307 verse 6.3

- ^ Sanskrit Original: द्वे वाव ब्रह्मणो रूपे मूर्तं चामूर्तं च । अथ यन्मूर्तं तदसत्यम् यदमूर्तं तत्सत्यम् तद्ब्रह्म तज्ज्योतिः यज्ज्योतिः स आदित्यः स वा एष ओमित्येतदात्माभवत् | Maitrayani Upanishad Wikisource;

English Translation: Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 347 - ^ Maitri Upanishad – Sanskrit Text with English Translation[permanent dead link] EB Cowell (Translator), Cambridge University, Bibliotheca Indica, page 258

- ^ Paul Deussen (Translator), Sixty Upanisads of the Veda, Vol 2, Motilal Banarsidass (2010 Reprint), ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 580-581

- ^ Eduard Roer, Mundaka Upanishad[permanent dead link] Bibliotheca Indica, Vol. XV, No. 41 and 50, Asiatic Society of Bengal, page 144

- ^ Hume translates this as "imperishable Brahma", Max Muller translates it as "indestructible Brahman"; see: Max Muller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Mundaka Upanishad, Oxford University Press, page 36

- ^ The Sanskrit word used is Vyadh, which means both "penetrate" and "know"; Robert Hume uses penetrate, but mentions the second meaning; see: Robert Hume, Mundaka Upanishad, Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, page 372 with footnote 1

- ^ Robert Hume, Mundaka Upanishad, Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 372-373

- ^ Charles Johnston, The Mukhya Upanishads: Books of Hidden Wisdom, (1920–1931), The Mukhya Upanishads, Kshetra Books, ISBN 978-1495946530 (Reprinted in 2014), Archive of Mundaka Upanishad, pages 310-311 from Theosophical Quarterly journal

- ^ Mundaka Upanishad, in Upanishads and Sri Sankara's commentary – Volume 1: The Isa Kena and Mundaka, SS Sastri (Translator), University of Toronto Archives, page 144 with section in 138-152

- ^ a b c d e f Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 605-637

- ^ a b c d e f g Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 391–393

- ^ Charles Johnston, The Measures of the Eternal – Mandukya Upanishad Theosophical Quarterly, October, 1923, pages 158-162

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 308

- ^ Max Muller, Shvetashvatara Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part II, Oxford University Press, page 237

- ^ Robert Hume (1921), Shvetashvatara Upanishad 1.14 – 1.16, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 396-397 with footnotes

- ^ John A Grimes (1995). Ganapati: Song of the Self. State University of New York Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-7914-2439-1.

- ^ Stephen Alter (2004), Elephas Maximus, Penguin, ISBN 978-0143031741, page 95

- ^ Grimes 1995, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Chinmayananda 1987, p. 127, In Chinmayananda's numbering system, this is upamantra 8..

- ^ a b Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, page 164

- ^ https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/9/verse/16-17

- ^ a b Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, page 271

- ^ Translator: KT Telang, Editor: Max Muller, The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita at Google Books, Routledge Print, ISBN 978-0700715473, page 120

- ^ a b c The Yogasutras of Patanjali Charles Johnston (Translator), page 15

- ^ The Vishnu-Dharma Vidya [Chapter CCXXI]. 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Indian Century - OM". www.indiancentury.com.

- ^ Guy Beck (1995), Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812611, page 154

- ^ Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Purāṇas. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447025225.

- ^ "Adi Parashakti - The Divine Mother". TemplePurohit - Your Spiritual Destination Bhakti, Shraddha Aur Ashirwad. 1 August 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Swami Narayanananda (1960). The Primal Power in Man: The Kundalini Shakti. Health Research Books. ISBN 9780787306311.

- ^ a b von Glasenapp 1999, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Om – significance in Jainism, Languages and Scripts of India, Colorado State University

- ^ "Namokar Mantra". Digambarjainonline.com. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Samuel, Geoffrey (2005). Tantric Revisionings: New Understandings of Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120827523.

- ^ "Vajrayana Buddhism Origins, Vajrayana Buddhism History, Vajrayana Buddhism Beliefs". www.patheos.com. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ ""OM" - THE SYMBOL OF THE ABSOLUTE". Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Olsen, Carl (2014). The Different Paths of Buddhism: A Narrative-Historical Introduction. Rutgers University Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-8135-3778-8.

- ^ Getty, Alice (1988). The Gods of Northern Buddhism: Their History and Iconography. Dover Publications. pp. 29, 191–192. ISBN 978-0-486-25575-0.

- ^ "Om Mani Padme Hum by The Dalai Lama". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ C. Alexander Simpkins; Annellen M. Simpkins (2009). Meditation for Therapists and Their Clients. W.W. Norton. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0-393-70565-2.

- ^ C. Alexander Simpkins; Annellen M. Simpkins (2009). Meditation for Therapists and Their Clients. W.W. Norton. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-393-70565-2.

- ^ a b c Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JAANUS), "A un" (阿吽), 2001, retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ Daijirin Japanese dictionary, 2008, Monokakido Co., Ltd.

- ^ a b Snodgrass, Adrian (2007). The Symbolism of the Stupa, Motilal Banarsidass. p. 303. ISBN 978-8120807815.

- ^ a b Baroni, Helen J. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism. Rosen Publishing. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6.

- ^ Komainu and Niô Dentsdelion Antiques Tokyo Newsletter, Volume 11, Part 3 (2011)

- ^ Ball, Katherine (2004). Animal Motifs in Asian Art. Dover Publishers. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-486-43338-7.

- ^ Arthur, Chris (2009). Irish Elegies. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-230-61534-2.

- ^ a b c Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2002). "The Sikhs". In Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo (ed.). The religious traditions of Asia: religion, history, and culture. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 114. ISBN 0-7007-1762-5.

- ^ Singh, Wazir (1969). Aspects of Guru Nanak's philosophy. Lahore Book Shop. p. 20. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

the 'a,' 'u,' and 'm' of aum have also been explained as signifying the three principles of creation, sustenance and annihilation. ... aumkār in relation to existence implies plurality, ... but its substitute Ik Onkar definitely implies singularity in spite of the seeming multiplicity of existence. ...

- ^ Mahinder Gulati (2008), Comparative Religious And Philosophies : Anthropomorphlsm And Divinity, Atlantic, ISBN 978-8126909025, pages 284-285; Quote: "While Ek literally means One, Onkar is the equivalent of the Hindu "Om" (Aum), the one syllable sound representing the holy trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva - the God in His entirety."

- ^ Wazir Singh (1969), Guru Nanak's philosophy, Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 1, Issue 1, page 56

- ^ a b c Pashaura Singh (2014), in The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies (Editors: Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199699308, page 227

- ^ SS Kohli (1993), The Sikh and Sikhism, Atlantic, ISBN 81-71563368, page 35, Quote: "Ik Aumkara is a significant name in Guru Granth Sahib and appears in the very beginning of Mul Mantra. It occurs as Aum in the Upanishads and in Gurbani, the Onam Akshara (the letter Aum) has been considered as the abstract of three worlds (p. 930). According to Brihadaranyaka Upanishad "Aum" connotes both the transcendent and immanent Brahman.

- ^ "Liber Samekh". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Magick in Theory and Practice - Chapter 7". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (1997). Magick : Liber ABA, book four, parts I-IV (Second revised ed.). San Francisco, CA. ISBN 9780877289197.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Crowley, Aleister (2016). Liber XV : Ecclesiae Gnosticae Catholicae Canon Missae. Gothenburg. ISBN 9788393928453.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Messerle, Ulrich. "Graphics of the Sacred Symbol OM". Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

Sources

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1376-6

Further reading

- Just say Om Joel Stein, Time Magazine Archives

- Kumar, S.; Nagendra, H.; Manjunath, N.; Naveen, K.; Telles, S. (2010). "Meditation on OM: Relevance from ancient texts and contemporary science". International Journal of Yoga. 3 (1): 2–5. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.66771. PMC 2952121. PMID 20948894.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Autonomic changes during "OM" meditation Telles et al. (1995)

- Francke, A. H. (1915). "The Meaning of the "Om-mani-padme-hum" Formula". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 397–404. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00048425. JSTOR 25189337.

- "Analysis of Acoustic of "OM " Chant to Study It's [sic] Effect on Nervous System". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.186.8652.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kumar, Uttam; Guleria, Anupam; Khetrapal, Chunni Lal (2015). "Neuro-cognitive aspects of "OM" sound/syllable perception: A functional neuroimaging study". Cognition and Emotion. 29 (3): 432–441. doi:10.1080/02699931.2014.917609. PMID 24845107. S2CID 20292351.

- The Mantra Om: Word and Wisdom Swami Vivekananda

External links

Media related to Aum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aum at Wikimedia Commons

![Assamese, Bengali[a]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/47/Om_symbol.gif/100px-Om_symbol.gif)

![Devanagari[b], Gujarati[c]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Aum_Om_black.svg/97px-Aum_Om_black.svg.png)

![Gurmukhi[d], Ik Onkar](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Ek_onkar.svg/100px-Ek_onkar.svg.png)

![Jain symbol[e]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d7/Om_ja%C3%AFn_orange.svg/80px-Om_ja%C3%AFn_orange.svg.png)

![Lepcha[f]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Lepcha_Om.png/100px-Lepcha_Om.png)

![Limbu[g]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Limbu_Om.png/100px-Limbu_Om.png)

![Meitei Mayek- Anji symbol[h]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Om_-_Anji_in_Meetei_Mayek.png/60px-Om_-_Anji_in_Meetei_Mayek.png)

![Modi[i]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Om_in_Modi_script.png/88px-Om_in_Modi_script.png)

![Odia[j]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/24/Odia_Om_symbol.png/80px-Odia_Om_symbol.png)

![Odia (Om joint symbol)[k]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Odia_Om_sign.png/99px-Odia_Om_sign.png)

![Pracalit[l]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Om_in_Pracalit%28Newa%29_script.png/71px-Om_in_Pracalit%28Newa%29_script.png)

![Sharada[m]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Om_in_Sharada_script.png/75px-Om_in_Sharada_script.png)

![Siddham[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Om_in_Siddham_script.png/86px-Om_in_Siddham_script.png)

![Soyombo[o]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/Soyombo_Om_symbol.png/54px-Soyombo_Om_symbol.png)

![Takri[p]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Om_in_Takri_script.png/81px-Om_in_Takri_script.png)

![Tibetan[q]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Om_tibetain-red.svg/100px-Om_tibetain-red.svg.png)

![Tirhuta/Mithilakshar[r]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Om_in_Tirhuta_script.png/100px-Om_in_Tirhuta_script.png)

![Balinese[s]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/47/Bali_Omkara_Red.png/75px-Bali_Omkara_Red.png)

![Burmese[t]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Om_in_Burmese_script.png/73px-Om_in_Burmese_script.png)

![Chakma[u]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Om_in_Chakma_script.png/86px-Om_in_Chakma_script.png)

![Cham- Homkar symbol [v]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Cham_Homkar_%28Om%29_symbol.jpg/92px-Cham_Homkar_%28Om%29_symbol.jpg)

![Grantha[w]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8b/Om_in_Grantha_script.png/87px-Om_in_Grantha_script.png)

![Javanese[x]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/de/Simbol_aum.png/60px-Simbol_aum.png)

![Kannada[y]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Kannada_OM.png/100px-Kannada_OM.png)

![Khmer[z]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Om_in_Khmer_script.png/52px-Om_in_Khmer_script.png)

![Khmer sacred symbol- known as Aom, Unalaom or Komutr[aa]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Khmer_Sacred_Symbol%2C_Om_or_Unalom.png/75px-Khmer_Sacred_Symbol%2C_Om_or_Unalom.png)

![Lao[ab]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Om_in_Lao_script.png/100px-Om_in_Lao_script.png)

![Malayalam[ac]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Ohm_Malayalam.png/100px-Ohm_Malayalam.png)

![Sinhala[ad]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/71/Sinhala_Om_symbol.png/100px-Sinhala_Om_symbol.png)

![Tamil[ae]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Tamil_Om.svg/100px-Tamil_Om.svg.png)

![Telugu[af]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Om_in_telugu.png/100px-Om_in_telugu.png)

![Thai[ag]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Thai_Om_symbol.png/95px-Thai_Om_symbol.png)

![Thai sacred symbol- known as Om, Unalome or Khomut[ah]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Thai_Khomut_symbol.png/54px-Thai_Khomut_symbol.png)

![Chinese[ai]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/Om_cinese.JPG/100px-Om_cinese.JPG)

![Hangul[aj]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/Korean_Om.png/97px-Korean_Om.png)

![Mongolian[al]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Om_in_Mongolian_script.png/72px-Om_in_Mongolian_script.png)