B movie

Template:Redirect6 The term B movie originally referred to a motion picture made on a low or modest budget and intended for distribution as the less-publicized, bottom half of a double feature during the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood. Although the U.S. production of movies intended as second features largely ceased by the end of the 1950s, the term B movie continues to be used in a broader sense, referring to any low-budget, commercial motion picture meant neither as an arthouse film nor as pornography. In its post–Golden Age usage, there is ambiguity on both sides: on the one hand, many B movies display a high degree of craft and aesthetic ingenuity; on the other, the primary interest of many inexpensive exploitation movies is prurient. In some cases, both are true.

In either usage, most B movies are representative of a particular genre—the Western was a Golden Age B movie staple, while low-budget science-fiction and horror films became more popular in the 1950s. Early B movies were often part of series in which the star repeatedly played the same character. Almost always shorter than the top-billed films they were paired with, many had running times of 70 minutes or less. The term connoted a general perception that B movies were inferior to the more handsomely budgeted headliners; individual B films were often ignored by critics. Latter-day B movies still sometimes inspire multiple sequels, but series are less common. As the average running time of A films has increased, so has that of B pictures. In its current usage, the term has two primary and somewhat contradictory connotations: it may be used to indicate an opinion that a certain movie is (a) a genre film with minimal artistic ambitions or (b) a lively, energetic film uninhibited by the constraints imposed on more expensive projects and unburdened by the conventions of putatively "serious" independent film.

From their beginnings to the present day, B movies have been an important means of entry into the motion picture industry. Celebrated filmmakers such as Anthony Mann and Jonathan Demme learned their craft in B movies, which also gave émigré directors from Europe such as Douglas Sirk an opportunity to establish themselves in Hollywood. B movies are where actors such as Robert Mitchum and Jack Nicholson got their starts, and the B's have also provided work for former A-movie actors, such as Vincent Price and Karen Black. Some actors, such as Bela Lugosi and Sybil Danning, worked in B movies for most of their careers. The terms drive-in movie and midnight movie, which emerged in association with specific historical phenomena, are now roughly synonymous with B movie. The terms C movie and Z movie describe progressively lower grades of films in the category. A more recently coined synonym is psychotronic movie.

History

Roots of the B movie: 1920s

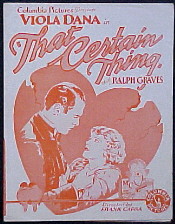

It is not clear that the term B movie (or B film or B picture) was in general use before the 1930s, but a similar concept was already well established. In 1927–28, at the end of the silent era, the production cost of an average feature from Hollywood's leading studios ranged from $190,000 at Fox to $275,000 at MGM. That average reflected both "specials" that might cost as much as $1 million and films made quickly for around $50,000. These cheaper films allowed the studios to derive maximum value from facilities and contracted staff in between a studio's more important productions, while also breaking in new personnel.[2] Studios in the minor leagues of the industry, such as Columbia Pictures and Film Booking Offices of America (FBO), focused on exactly those sort of cheap productions; their movies, with relatively short running times, targeted theaters that had to economize on rental and operating costs—particularly those in small towns and so-called neighborhood venues, or "nabes," in big cities. Even smaller, so-called Poverty Row outfits made films whose production costs might run as low as $3,000, seeking a profit through whatever bookings they could pick up in the gaps left by the larger concerns.[3]

With the widespread arrival of sound film in American theaters in 1929, many independent exhibitors began dropping the then-dominant presentation model, which involved live acts and a broad variety of shorts before a single featured film. A new programming scheme developed that would soon become standard practice: a newsreel, a short and/or a serial, and a cartoon, followed by a double feature. The second feature, which actually screened before the main event, cost the exhibitor less per minute than the equivalent running time in shorts. The majors' "clearance" rules favoring their affiliated theaters prevented the independents' timely access to top-quality films; the second feature allowed them to promote quantity instead.[4] The B movie also gave the program "balance"—the practice of pairing different sorts of features suggested to potential customers that they could count on something of interest no matter what specifically was on the bill. As the president of one Poverty Row company would later put it, "Not everybody likes to eat cake. Some people like bread, and even a certain number of people like stale bread rather than fresh bread."[5] The low-budget picture of the 1920s naturally transformed into the second feature, the B movie, of the 1930s and 1940s—the most reliable bread of Hollywood's Golden Age.

B's in the Golden Age of Hollywood (1): 1930s

The major studios, at first resistant to the B feature, soon adapted. All established "B units" to provide films for the expanding second-feature market. Block booking became standard practice: in order to get access to a studio's attractive A pictures, many theaters were obliged to rent the company's entire output for a season. With the B films rented at a flat fee (rather than the box office percentage basis of A films), rates could be set that virtually guaranteed the profitability of every B movie. The parallel practice of blind bidding largely freed the majors from worrying about the quality of their B's—even when booking in less than seasonal blocks, exhibitors had to buy most pictures sight unseen. The five largest studios—MGM, Paramount, Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO (descendant of FBO)—had the added advantage of belonging to companies with sizable theater chains, further securing the bottom line. Poverty Row studios, from modest outfits like Mascot Pictures and Sono Art–World Wide down to shoestring operations, made exclusively B movies, serials, and other shorts; they also distributed totally independent productions and imported films. These studios were in no position to directly block book; instead, they mostly sold regional distribution exclusivity to "states rights" distributors, who in turn peddled blocks of films to exhibitors, typically six or more movies featuring the same star (a relative status on Poverty Row).[6] Two studios in the middle—the "major-minors" Universal and Columbia, moving up in rank—had production lines roughly similar to the top Poverty Row concerns, if somewhat better endowed in general, and with a few up-market productions each year as well. They had few or no theaters, but they did have major-league-level distribution exchanges.[7]

In the standard Golden Age model, the industry's top product, its A films, premiered at a select number of first-run houses in major cities, virtually all of them owned by one of the five largest studios, the so-called Big Five. Across North America, there were approximately 450 first-run houses; a 100-screen debut was a grand opening. Double features were not the rule at these prestigious venues. As described by historian Edward Jay Epstein, "During these first runs, films got their reviews, garnered publicity, and generated the word of mouth that served as the principal form of advertising."[8] Then it was off to the subsequent-run market where the double feature prevailed. At the larger local venues controlled by the majors, movies might turn over on a weekly basis. At the thousands of smaller, independent theaters, programs often changed two or three time a week. To keep up with the constant demand for new B product, the low end of Poverty Row turned out a stream of micro-budget movies rarely much more than sixty minutes long; these were known as "quickies" for their tight production schedules—a week was about average, four days not unheard of.[9] As historian Brain Taves describes, "Many of the poorest theaters, such as the 'grind houses' in the larger cities, screened a continuous program emphasizing action with no specific schedule, sometimes offering six quickies for a nickel in all-night show that changed daily."[10] Many small theaters never saw a big-studio A film, getting their movies from the states rights concerns that handled almost exclusively Poverty Row product. Millions of Americans went to their local theaters as a matter of course: for an A picture, along with the trailers, or screen previews, that had presaged its arrival, "[t]he new film's title on the marquee and the listings for it in the local newspaper constituted all the advertising most movies got."[11] Aside from at the theater itself, B films might not be advertised at all.

The introduction of sound had driven costs higher. In 1930, the beginning of the Golden Age's first full decade, the average U.S. feature film cost $375,000 to produce.[12] A broad range of motion pictures occupied the B category. The leading studios made not only clear-cut A and B films, but also movies classifiable as "programmers" (also "in-betweeners" or "intermediates"): "Depending on the prestige of the theater and the other material on the double bill, a programmer could show up at the top or bottom of the marquee."[13] On Poverty Row, many B's were made on budgets that would have barely covered petty cash on a major's A film, with costs at the bottom of the industry running as low as $5,000.[14] By the middle of the 1930s, the double feature was the dominant exhibition model across the country, and the majors responded. In 1935, B-movie production at Warner Bros. was raised from 12 to 50 percent of the studio's total output. The unit was headed by Bryan Foy, known as the "Keeper of the B's."[15] At Fox, which also shifted half of its production line into B territory, Sol Wurtzel was similarly in charge of more than twenty movies a year during the late 1930s.

A number of the top Poverty Row firms consolidated: Sono Art joined another company to create Monogram Pictures early in the decade. In 1935, Monogram, Mascot, and several smaller studios merged to form Republic Pictures. After just over a year, the heads of Monogram pulled out and revived their company. Into the 1950s, Republic and Monogram released films that tended to be roughly on par with the low end of the majors' output. Less sturdy Poverty Row concerns—with a penchant for grand sobriquets like Conquest, Empire, Imperial, and Peerless—continued to churn out dirt-cheap quickies.[16] Joel Finler has analyzed the average length of feature film releases in 1938, indicating the studios' relative emphasis on B production (United Artists directly produced no features, focusing instead on the distribution of prestigious films from independent outfits):[17]

Studio Category Avg. duration MGM Big Five 87.9 minutes Paramount Big Five 76.4 minutes 20th Century-Fox Big Five 75.3 minutes Warner Bros. Big Five 75.0 minutes RKO Big Five 74.1 minutes United Artists Little Three 87.6 minutes Columbia Little Three 66.4 minutes Universal Little Three 66.4 minutes Grand National[18] Poverty Row 63.6 minutes Republic Poverty Row 63.1 minutes Monogram Poverty Row 60.0 minutes

Taves estimates that half of the films produced by the eight majors in the 1930s were B movies. Calculating in the three hundred or so films made annually by the many Poverty Row firms, approximately 75 percent of Hollywood movies from the decade, more than four thousand pictures, are classifiable as B's.[19]

The Western was by far the predominant B genre in both the 1930s and, to a lesser degree, the 1940s.[20] Film historian Jon Tuska has argued that "the 'B' product of the Thirties—the Universal films with [Tom] Mix, [Ken] Maynard, and [Buck] Jones, the Columbia features with Buck Jones and Tim McCoy, the RKO George O'Brien series, the Republic Westerns with John Wayne and the Three Mesquiteers...achieved a uniquely American perfection of the well-made story."[21] At the far end of the industry, Poverty Row's Ajax put out oaters starring Harry Carey, then in his fifties. The Weiss outfit had the Range Rider series, the American Rough Rider series, and the Morton of the Mounted "northwest action thrillers."[22] One notable low-budget oater of the era, produced totally outside of the studio system, made money off an outrageous concept: a Western with an all-midget cast, The Terror of Tiny Town (1938) was such a success in its independent bookings that Columbia picked it up for distribution.[23]

Series of various genres were particularly popular during the first decade of sound film. At just one major studio, Fox, B series included "Charlie Chan, Mr. Moto, Sherlock Holmes, Michael Shayne, the Cisco Kid, George O'Brien Westerns [before his move to RKO], the Gambini sports films, the Roving Reporters, the Camera Daredevils, the Big Town Girls, the hotel for women, the Jones Family, the Jane Withers children's films, Jeeves, [and] the Ritz Brothers."[24] These feature-length series films are not to be confused with the short, cliffhanger-structured serials that sometimes appeared on the same program. As with serials, however, many series were specifically intended to interest young people—some of the theaters that twin-billed part-time might run a "balanced" or entirely youth-oriented double feature as a matinee and then a single film for a more mature audience at night. In the words of a contemporary Gallup industry report, afternoon moviegoers, "composed largely of housewives and children, want quantity for their money while the evening crowds want 'something good and not too much of it.'"[25] Series films are often unquestioningly consigned to the B-movie category, but even here there is ambiguity:

[T]he most profitable B pictures functioned much like the comic strips in the daily newspapers, showing the continuing adventures of Roy Rogers [Republic], Boston Blackie [Columbia], the Bowery Boys [Warner Bros./Universal], Blondie and Dagwood [Columbia], Charlie Chan [Fox/Monogram], and so on. Even a major studio like MGM [the industry leader from 1931 through 1941] was equipped with a so-called B unit that specialized in these serial [sic] productions. At MGM, however, the Andy Hardy, Dr. Kildaire, and Thin Man films were made with major stars and with what some organizations would have considered A budgets.[26]

For some series, even a major studio's B budget was far out of reach: Poverty Row's Consolidated Pictures, backed by Weiss, featured Tarzan, the Police Dog in a series with the proud name of Melodramatic Dog Features.[27]

B's in the Golden Age of Hollywood (2): 1940s

By 1940, the average production cost of an American feature was $400,000, a negligible increase over ten years.[28] A number of small Hollywood companies had folded around the turn of the decade, including the ambitious Grand National, but a new firm, Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), emerged as third in the Poverty Row hierarchy behind Republic and Monogram. The double feature, never universal, was still the prevailing exhibition model: in 1941, 50 percent of theaters were double-billing exclusively, with others screening under the policy part-time.[29] In the early 1940s, legal pressure forced the studios to replace seasonal block booking with packages generally limited to five pictures. Restrictions were also placed on the majors' ability to enforce blind bidding.[30] These were crucial factors in the progressive shift by most of the Big Five over to A-film production, making the smaller studios even more important as B-movie suppliers. Genre pictures made at very low cost remained the backbone of Poverty Row, with even Republic's and Monogram's budgets rarely climbing over $200,000. Among the established studios, Monogram was exploring fresh territory with what were being called "exploitation pictures." Variety defined these as "films with some timely or currently controversial subject which can be exploited, capitalized on in publicity or advertising."[31] Many smaller Poverty Row firms were folding because there simply wasn't enough money to go around: the eight majors, with their proprietary distribution exchanges, were now "taking in around 95 percent of all domestic (U.S. and Canada) rental receipts."[32]

Considerations beside cost made the line between A and B movies ambiguous. Films shot on B-level budgets were occasionally marketed as A pictures or emerged as sleeper hits: One of 1943's biggest films was Hitler's Children, an 82-minute-long RKO thriller made for a fraction over $200,000. It earned more than $3 million in rentals, industry language for a distributor's share of gross box office receipts.[33] A pictures, particularly in the realm of film noir, sometimes echoed visual styles generally associated with cheaper films. Programmers, with their flexible exhibition role, were ambiguous by definition, leading in certain cases to historical confusion. Ronald Reagan, frequently identified as a "B-movie star," in fact often had leading parts not only in programmers but also run-of-the-mill A movies that were B's only in the sense of perceived aesthetic quality. As late as 1948, the double feature remained a popular exhibition mode—it was the standard screening policy at 25 percent of theaters and used part-time at an additional 36 percent.[34] The leading Poverty Row firms began to broaden their scope: In 1947, Monogram established a subsidiary, Allied Artists, as a development and distribution channel for relatively expensive films, mostly from independent producers. Around the same time, Republic launched a similar effort under the "Premiere" rubric.[35] In 1947 as well, PRC was subsumed by Eagle-Lion, a British company seeking entry to the American market. Warners' former Keeper of the B's, Brian Foy, was installed as production chief.[36]

In the 1940s, RKO—the weakest of the Big Five throughout its history—stood out among the industry's largest companies for its focus on B pictures. From a latter-day perspective, the most famous of the major studios' Golden Age B units is Val Lewton's horror unit at RKO. Lewton produced such moody, mysterious films as Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and The Body Snatcher (1945), directed by Jacques Tourneur, Robert Wise, and others who would become renowned only later in their careers or entirely in retrospect. The movie now widely described as the first classic film noir—Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a 64-minute B—was produced at RKO, which would release many additional melodramatic thrillers in a similarly stylish vein during the decade. The other major studios also turned out a considerable number of movies now identified as noir during the 1940s. Though many of the best-known film noirs were A-level productions, most 1940s pictures in the mode were either of the ambiguous programmer type or destined straight for the bottom of the bill. In the decades since, these cheap entertainments, generally dismissed at the time, have become some of the most treasured products of Hollywood's Golden Age.[38]

In one sample year, 1947, RKO produced in addition to several noir programmers and A pictures, two straight B noirs: Desperate, directed by Anthony Mann, and The Devil Thumbs a Ride, directed by Felix Feist. Ten true B noirs that year came from Poverty Row's big three—Republic, Monogram, and PRC/Eagle-Lion—and one from tiny Screen Guild. Three majors beside RKO contributed a total of five more. In addition to those eighteen unambiguous B noirs, there were an additional dozen or so noir programmers out of Hollywood.[39] Still, most of the majors' low-budget production remained the sort now largely ignored. RKO's representative output included the Mexican Spitfire and Lum and Abner comedy series, thrillers featuring the Saint and the Falcon, Westerns starring Tim Holt, and Tarzan movies with Johnny Weissmuller. Jean Hersholt played Dr. Christian in six films between 1939 and 1941. The Courageous Dr. Christian (1940) was a standard entry: "In the course of an hour or so of screen time, the saintly physician managed to cure an epidemic of spinal meningitis, demonstrate benevolence towards the disenfranchised, set an example for wayward youth, and calm the passions of an amorous old maid."[40]

Down in Poverty Row, low budgets led to less palliative fare. Republic aspired to major-league respectability while making many cheap and modestly budgeted Westerns, but there wasn't much from the bigger studios that compared with Monogram "exploitation pictures" like juvenile delinquency exposé Where Are Your Children? (1943) and the prison film Women in Bondage (1943).[41] In 1947, PRC's The Devil on Wheels brought together teenagers, hot rods, and death. The little studio had its own house auteur: with his own crew and relatively free rein, director Edgar G. Ulmer was known as "the Capra of PRC."[42] Ulmer made films of every generic stripe: His Girls in Chains was released in May 1943, six months before Women in Bondage; by the end of the year, Ulmer had also made the teen-themed musical Jive Junction as well as Isle of Forgotten Sins, a South Seas adventure set around a brothel.

Transition I/The B movie in the television age: 1950s

In 1948, a Supreme Court ruling in a federal antitrust suit against the majors outlawed block booking and led to the Big Five divesting their theater chains. With audiences draining away to television and studios scaling back production schedules, the classic double feature vanished from many American theaters during the 1950s. The major studios promoted the benefits of recycling, offering former headlining movies as second features in the place of traditional B films.[43] With television airing many classic Westerns as well as producing its own original Western series, the cinematic market for B oaters in particular was drying up. After barely inching forward in the 1930s, the average U.S. feature production cost had essentially doubled over the 1940s, reaching $1 million by the turn of the decade—a 93 percent rise after adjusting for inflation.[44]

The first prominent victim of the changing market was Eagle-Lion, which released its last films in 1951. By 1953, the old Monogram brand had disappeared, the company having adopted the identity of its higher-end subsidiary, Allied Artists. The following year, Allied released Hollywood's last B series Westerns. Non-series B Westerns would continue to come out for a few more years, but Republic Pictures, long associated with cheap sagebrush sagas, was out of the filmmaking business by the end of the decade. In other genres, Allied Artists kept its Bomba the Jungle Boy series going through 1955, while Universal stuck with Ma and Pa Kettle into 1957.[45] RKO, weakened by years of mismanagement, exited the movie industry that year.[46] Hollywood's A product was getting longer—the top ten box-office releases of 1940 had averaged 112.5 minutes; the average length of 1955's top ten was 123.4.[47] In their modest way, the B's were following suit. The age of the hour-long feature film was past; 70 minutes was now roughly the minimum. While the Golden Age–style second feature was dying, B movie was still used to refer to any low-budget genre film featuring relatively unheralded performers ("B actors"). The term retained its earlier suggestion that such movies relied on formulaic plots, "stock" character types, and simplistic action or unsophisticated comedy. At the same time, the realm of the B movie was becoming increasingly fertile territory for experimentation, both serious and outlandish.

Ida Lupino, well known as an actress, established herself as Hollywood's sole female director of the era. In short, low-budget pictures made for her production company, The Filmakers, Lupino explored virtually taboo subjects such as rape in 1950's Outrage (released by RKO) and 1953's self-explanatory The Bigamist (an entirely independent project). Her most famous directorial effort, The Hitch-Hiker, a 1953 RKO release, is often referred to as the only classic film noir directed by a woman.[48] That same year, RKO put out another historically notable film made at low cost: Split Second concludes in a nuclear test range, making it perhaps the first example of an "atomic noir." The most famous such movie, the independently produced Kiss Me Deadly (1955), typifies the persistently murky middle ground between the A and B picture: a "programmer capable of occupying either half of a neighbourhood theatre's double-bill, [it was] budgeted at approximately $400,000. [Its] distributor, United Artists, released around twenty-five programmers with production budgets between $100,000 and $400,000 in 1955. For UA, these movies served to spread the overhead costs of their distribution operation rather than to make profits in themselves."[49] The film's length, 106 minutes, is A level, but its star, Ralph Meeker, had previously appeared in only one major film. Its source is pure pulp, one of Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer novels, but Robert Aldrich's direction is self-consciously aestheticized. The result is a brutal genre picture that also evokes contemporary anxieties about what was often spoken of simply as the Bomb.

The fear of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, along with less expressible qualms about the effects of radioactive fallout from America's own atomic tests, energized many of the era's genre films. Science fiction, horror, and various hybrids of the two were now of central economic importance to the low-budget end of the business. Most down-market films of the type—like those produced by William Alland at Universal (e.g., Creature from the Black Lagoon [1954]) and Sam Katzman at Columbia (e.g., Earth vs. the Flying Saucers [1956])—sought to provide no more than simple diversion. But these were genres whose fantastic nature could also be used as cover for mordant cultural observations often difficult to make in mainstream movies. Director Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), produced by Walter Wanger for $300,000 and released by Allied Artists, treats conformist pressures and the evil of banality in haunting, allegorical fashion.[51] The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), directed by Bert I. Gordon, is both a monster movie that happens to depict the horrific effects of radiation exposure and "a ferocious cold-war fable [that] spins Korea, the army's obsessive secrecy, and America's post-war growth into one fantastic whole."[52]

The Amazing Colossal Man was released by a new company whose name was much bigger than its budgets. American International Pictures (AIP), founded in 1956 by James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff in a reorganization of their American Releasing Corporation (ARC), soon became the leading U.S. studio devoted entirely to B-priced productions. American International helped keep the original-release double bill alive through paired packages of its films: these movies were low-budget, but the economic model was different from that of the traditional B movie—instead of a flat rate, they were rented out on a percentage basis, like A films.[53] I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) is perhaps the best known AIP film of the era. As its title suggests, the studio relied on both fantastic genre subjects and new, teen-oriented angles. If Hot Rod Gang (1958) worked, then why not hot rod horror? Result: Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow (1959). AIP is credited with having "led the way...in demographic exploitation, target marketing, and saturation booking, all of which would become standard procedure for the majors in planning and releasing their mass-market 'event' films" by the late 1970s.[54] In terms of content, the majors were already there, with "J.D." movies such as Warner Bros.' Untamed Youth (1957) and MGM's High School Confidential (1958), both starring Mamie Van Doren.

In 1954, a young filmmaker named Roger Corman received his first screen credits as writer and associate producer of Allied Artists' Highway Dragnet. Corman soon independently produced his first movie, The Monster from the Ocean Floor, on a $12,000 budget and a six-day shooting schedule.[55] Among the six films he worked on in 1955, Corman produced and directed the first official ARC release, Apache Woman, and Day the World Ended, half of Arkoff and Nicholson's first twin-bill package. Corman would go on to direct over fifty feature films through 1990. As of 2007, he remained active as a producer, with more than 350 movies to his credit. Often referred to as the "King of the B's," the historically sensitive Corman has said that "to my way of thinking, I never made a 'B' movie in my life," as B movies in the classic sense were dying out by the time he began making pictures. He prefers to describe his metier as "low-budget exploitation films."[56] In later years Corman, both with AIP and as head of his own companies, would help launch the careers of Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Robert Towne, and Robert De Niro, among many others.

In the late 1950s, William Castle became known as the great innovator of the B-movie publicity gimmick. Audiences of Macabre (1958), an $86,000 production distributed by Allied Artists, were invited to take out insurance policies to cover potential death from fright. The 1959 creature feature The Tingler, distributed by Columbia, featured Castle's most famous gimmick, Percepto: at the film's climax, buzzers attached to select theater seats would unexpectedly rattle a few audience members, prompting either appropriate screams or even more appropriate laughter.[57] With such films, Castle "combine[d] the saturation advertising campaign perfected by Columbia and Universal in their Sam Katzman and William Alland packages with centralized and standardized publicity stunts and gimmicks that had previously been the purview of the local exhibitor."[58]

The growth of the drive-in theater market was one of the major spurs to the expansion of the independent low-budget film industry. In 1946, there were approximately 300 drive-ins in the United States; a decade later, there were 4,500, one-quarter of all American cinemas.[59] Unpretentious pictures with simple, familiar plots and reliable shock effects were ideally suited for auto-based film viewing, with all its attendant distractions. The phenomenon of the drive-in movie became one of the defining symbols of American popular culture in the 1950s. At the same time, many local television stations began showing B genre films in late-night slots, popularizing the notion of the midnight movie.

Increasingly, American-made genre films were being joined by foreign movies acquired cheaply and dubbed for the U.S. market. In 1956, promoter Joseph E. Levine financed the shooting of new footage with American actor Raymond Burr that was edited into the Japanese sci-fi horror film Godzilla. In 1959, Levine's Embassy Pictures acquired the worldwide rights to a cheaply made movie starring American-born bodybuilder Steve Reeves. On top of a $125,000 purchase price, Levine then spent $1.5 million on advertising and publicity, a virtually unprecedented amount.[60] The New York Times was nonplussed: "Hercules, an Italianmade spectacle film dubbed in English, is the kind of picture that normally would draw little more than yawns in the film market...had it not been [launched] throughout the country with a deafening barrage of publicity. The exploitation film, which has been taken over by Warner Brothers for distribution, opened yesterday at 135 theatres in the New York area alone."[61] Levine counted on opening-weekend box office for his profits, booking the film "into as many cinemas as he could for a week's run, then withdrawing it before poor word-of-mouth withdrew it for him."[62] The strategy was a smashing success: the film earned $4.7 million in domestic rentals alone. Just as valuable to the bottom line, it was even more successful overseas.[63] Within a few decades, Hollywood would be dominated by both movies and an exploitation philosophy very like Levine's.

The golden age of exploitation (1): 1960s

Despite all the transformations in the industry, by 1961 the average production cost of an American feature film was still only $2 million—after adjusting for inflation, less than 10 percent more than it had been in 1950.[64] The traditional twin bill of B film preceding and balancing a subsequent-run A film had largely disappeared from American theaters. The AIP-style dual genre package was the new model. In July 1960, the latest Joseph E. Levine sword-and-sandals import, Hercules Unchained, opened at neighborhood theaters in New York. An 82-minute-long suspense film, Terror Is a Man, ran as a "co-feature" with a now familiar sort of exploitation gimmick: "The dénouement helpfully includes a 'warning bell' so the sensitive can 'close their eyes.'"[65] That year, Roger Corman took American International down a new road: "When they asked me to make two ten-day black-and-white horror films to play as a double feature, I convinced them instead to finance one horror film in color."[66] House of Usher typifies the continuing ambiguities of B-picture classification. It was clearly an A film by the standards of both director and studio, with the longest shooting schedule and biggest budget Corman had ever enjoyed. But it is seen in retrospect as a B movie—the schedule was still a mere fifteen days, the budget just $200,000, one-tenth the industry average.[67] B-movie aficionado John Reid reports once asking a neighborhood theater manager to define "B picture." The response: "Any movie that runs less than 80 minutes."[68] House of Usher's running time is close, 85 minutes. And despite its high status in studio terms, it was not screened alone, but in tandem with a crime melodrama asking the eternal question Why Must I Die?[69]

With the loosening of industry censorship constraints, the 1960s saw a major expansion in the production and commercial viability of a variety of B-movie subgenres that have come to be known collectively as exploitation films. The term gained broader application as well: Exploitation-style promotional practices had become standard practice at the lower-budget end of the industry; with the majors having exited traditional B production, exploitation became a way to refer to the entire field of low-budget genre films. The combination of intensive and gimmick-laden publicity with movies featuring vulgar subject matter along with often outrageous imagery dated back decades—before even The Terror of Tiny Town. Exploitation had originally defined truly fringe productions with a dose of shocking content, made at the lowest depths of Poverty Row or entirely outside the Hollywood system. Many graphically depicted the wages of sin in the context of promoting prudent lifestyle choices, particularly "sexual hygiene." Audiences might see explicit footage of anything from a live birth to a ritual circumcision.[70] Such films were not generally booked as part of movie theaters' regular schedules but rather presented as special events by traveling roadshow promoters (they might also appear as fodder for "grind houses," which typically had no regular schedule at all). The most famous of those promoters, Kroger Babb, was in the vanguard of marketing low-budget, sensationalistic films with a "100% saturation campaign," inundating the target audience with ads in almost any imaginable medium.[71] In the era of the traditional double feature, no one would have characterized these exploitation films as "B movies." As production and exhibition practices changed, so did the terms of definition.

In the early 1960s, exploitation movies in the original sense continued to appear: 1961's Damaged Goods, a cautionary tale about a young lady whose boyfriend’s promiscuity leads to venereal disease, comes complete with enormous, grotesque closeups of VD's physical manifestations.[72] At the same time, the concept of fringe exploitation was merging with a closely related and similarly venerable tradition: “nudie" films featuring nudist-camp footage or striptease artists like Bettie Page had simply been the softcore pornography of previous decades. As far back as 1933, This Nude World was "Guaranteed the Most Educational Film Ever Produced!"[73] In the late 1950s, as more of the old grind house theaters devoted themselves specifically to "adult" product, a few filmmakers began making nudies with greater attention to plot. Best known was Russ Meyer, who released his first successful narrative nudie, The Immoral Mr. Teas, in 1959. Five years later, on a sub-$100,000 budget, Meyer came out with Lorna, "a harder-edged film that combined sex with gritty realism and violence."[74] A talented director, Meyer would gain renown for what became known as sexploitation pictures such as Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) and Vixen! (1968). These films were largely relegated to the fringe circuit of "adult" theaters, while AIP teen movies with wink-wink titles like Beach Blanket Bingo (1965) and How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1966), starring Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon, played drive-ins and other reputable venues. Roger Corman's The Trip (1967) for American International, written by veteran AIP/Corman actor Jack Nicholson, never shows a fully bared, unpainted breast, but flirts with nudity throughout. The Meyer and Corman lines were drawing closer.

One of the most influential films of the era, on both B's and beyond, was Paramount's Psycho. Its $8.5 million in earnings against a production cost of $800,000 made it the most profitable movie of 1960.[75] Its mainstream distribution without the Production Code seal of approval helped weaken U.S. film censorship. And, as William Paul notes, this move into the horror genre by respected director Alfred Hitchcock was made, "significantly, with the lowest-budgeted film of his American career and the least glamorous stars. [Its] greatest initial impact...was on schlock horror movies (notably those from second-tier director William Castle), each of which tried to bill itself as scarier than Psycho."[76] Castle's first film in the Psycho vein was Homicidal (1961), an early step in the development of the slasher subgenre that would take off in the late 1970s. Blood Feast (1963), a movie about human dismemberment and culinary preparation made for approximately $24,000 by experienced nudie-maker Herschell Gordon Lewis, established a new, more immediately successful subgenre, the gore or splatter film. Lewis's business partner David F. Friedman drummed up publicity by distributing vomit bags to theatergoers—the sort of gimmick Castle had mastered—and arranging for an injunction against the film in Sarasota, Florida—the sort of problem exploitation films had long run up against, except Friedman had planned it.[77] This new breed of gross-out movie typifies the emerging sense of "exploitation"—the progressive adoption of traditional exploitation and nudie elements into horror, into other classic B genres, and into the low-budget film industry as a whole. Later in the decade, imports of the Italian giallo subgenre, often highly stylized films mixing sexploitation and ultraviolence, would fuel this trend.

The Production Code was officially scrapped in 1968, to be replaced by the first version of the modern rating system. That year, two horror films came out that heralded directions American filmmaking would take in the next decade, with major long-range consequences for the B film. One was a high-budget Paramount production, directed by the celebrated Roman Polanski and based on a bestselling novel by Ira Levin. Produced by B-horror veteran William Castle, Rosemary's Baby "took the genre up-market for the first time since the 1930s."[78] It was a critical success and the seventh-biggest box office hit of the year. The other was George Romero's now classic Night of the Living Dead, produced on weekends in and around Pittsburgh for $114,000. Essentially a war movie pitting a small group of humans against a zombie corps, it built on the achievement of B-genre predecessors like Invasion of the Body Snatchers in its subtextual exploration of social and political issues. The movie doubled as a highly effective thriller and an incisive allegory for both the Vietnam War and domestic racial conflicts. Its greatest influence, though, derived from its clever subversion of genre clichés and the connection made between its exploitation-style imagery, low-cost, truly independent means of production, and high rate of return: $3 million in earnings in 1968, with much more to come from various revivals.[79] With the Code gone and the X rating established, major studio A films like Midnight Cowboy could now show "adult" imagery, while the market for increasingly hardcore pornography exploded. In this transformed commercial context, work like Russ Meyer's gained a new legitimacy. In 1969, for the first time a Meyer film, Finders Keepers, Lovers Weepers!, was reviewed in the New York Times.[80] Soon, Corman would be putting out nudity-filled sexploitation pictures such as Private Duty Nurses (1971) and Women in Cages (1971).

In May 1969, the most important of all exploitation movies premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Much of its significance owes to the fact that it was produced for a respectable, if still modest, budget and released by a major studio. The project was first taken by one of its cocreators, Peter Fonda, to American International. Fonda had become AIP's top star in the Corman–directed The Wild Angels (1966), a biker movie, and The Trip, as in LSD. The idea Fonda pitched would combine those two proven themes. AIP was intrigued but balked at giving his collaborator, Dennis Hopper, also a studio alumnus, free directorial rein. Eventually they arranged a financing and distribution deal with Columbia, while two more graduates of the Corman/AIP exploitation mill joined the project: Jack Nicholson and cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs. The film (which incorporated another favorite exploitation theme, the redneck menace, as well as a fair amount of nudity) was brought in at a cost of $501,000. Easy Rider earned $19.1 million in rentals and became "the seminal film that provided the bridge between all the repressed tendencies represented by schlock/kitsch/hack since the dawn of Hollywood and the mainstream cinema of the seventies."[81]

The golden age of exploitation (2): 1970s

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a new generation of low-budget film companies emerged that drew from all the different lines of exploitation as well as the sci-fi and teen themes that had been a mainstay since the 1950s. Operations such as Roger Corman's New World Pictures, Cannon Films, and New Line Cinema brought exploitation films to mainstream theaters around the country. The major studios' top product was continuing to inflate in running time—in 1970, the ten biggest earners averaged 140.1 minutes.[82] The B's were keeping pace: In 1955, Corman had a producorial hand in five movies averaging 74.8 minutes. He played a similar part in five films originally released in 1970, two for AIP and three for his own New World: the average length was 89.8 minutes.[83] These films could turn a tidy profit. The first New World release, the biker movie Angels Die Hard, cost $117,000 to produce and took in more than $2 million at the box office.[84]

The biggest studio in the low-budget field remained a leader in exploitation's growth. In 1973, American International gave a shot to young director Brian De Palma. Reviewing Sisters, Pauline Kael observed that its "limp technique doesn't seem to matter to the people who want their gratuitous gore.... [H]e can't get two people talking in order to make a simple expository point without its sounding like the drabbest Republic picture of 1938."[85] Many examples of the so-called blaxploitation genre, featuring stereotype-filled stories revolving around drugs, violent crime, and prostitution, were the product of AIP. One of blaxploitation's biggest stars was Pam Grier, who began her career with a bit part in Russ Meyer's Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), followed by appearances in several New World pictures, including The Big Doll House (1971) and The Big Bird Cage (1972), both directed by Jack Hill. Hill also directed her best-known performances, in two AIP blaxploitation films: Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974). Grier has the distinction of starring in the first widely distributed movie to climax with a castration scene.

Blaxploitation was the first exploitation genre in which the major studios were central. Indeed, the United Artists release Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), directed by Ossie Davis, is seen as the first significant film of the type. Crossing over before the genre was even well established, Laurence Merrick's micro-budget independent The Black Angels (1970) followed by a few months.[86] But the movie that truly ignited the blaxploitation phenomenon, again completely independent, came in 1971: Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song is also perhaps the most outrageous example of the form—wildly experimental, borderline pornographic, and essentially a manifesto for a black American revolution. Melvin Van Peebles wrote, co-produced, directed, starred in, edited, and composed the music for the film, which was completed with a $50,000 loan from Bill Cosby.[87] Its distributor was small Cinemation Industries, then best known for releasing dubbed versions of the Italian Mondo Cane "shockumentaries" and the Swedish skin flick Fanny Hill, as well as for its one in-house production, The Man from O.R.G.Y. (1970). These were the sort of films that played in the "grind houses" of the day—many of them not outright porno theaters, but rather venues for all manner of exploitation cinema. The days of six quickies for a nickel were gone, but a continuity of spirit was evident.

In 1970, a low-budget crime drama shot in 16 mm by first-time American director Barbara Loden won the international critics' prize at the Venice Film Festival. Wanda is both a seminal event in the independent film movement and a classic B picture. The crime-based plot and often seedy settings would have suited a straightforward exploitation film or an old-school B noir. The sub-$200,000 production, for which Loden spent six years raising money, was praised by Vincent Canby for "the absolute accuracy of its effects, the decency of its point of view and...purity of technique."[88] Like Romero and Van Peebles, other filmmakers of the era made pictures that combined the gut-level entertainment of exploitation with biting social commentary. The first three features directed by Larry Cohen, Bone (1972), Black Caesar (1973), and Hell Up in Harlem (1973), were all nominally blaxploitation movies, but Cohen used them as vehicles for a satirical examination of race relations and the wages of dog-eat-dog capitalism. The gory horror film Deathdream (1974), directed by Bob Clark, is also an agonized protest of the war in Vietnam. Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg made serious-minded low-budget horror films whose implications are not so much ideological as psychological and existential: Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977), The Brood (1979). An Easy Rider with conceptual rigor, the movie that most clearly presaged the way in which exploitation content and artistic treatment would be combined in modestly budgeted films of later years was United Artists' biker-themed Electra Glide in Blue (1973), directed by James William Guercio.[89] The New York Times reviewer thought little of it: "Under different intentions, it might have made a decent grade-C Roger Corman bike movie—though Corman has generally used more interesting directors than Guercio."[90]

In the early 1970s, the growing practice of screening nonmainstream motion pictures as late shows, with the goal of building a cult film audience, brought the midnight movie concept home to the cinema, now in a countercultural setting—something like a drive-in movie for the hip.[91] One of the first films adopted by the new circuit in 1971 was the three-year-old Night of the Living Dead. The midnight movie success of low-budget pictures made entirely outside of the studio system, like John Waters's Pink Flamingos (1972), with its campy spin on exploitation, spurred the development of the independent film movement. The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), an inexpensive film from 20th Century-Fox that spoofed all manner of classic B-picture clichés, became an unparalleled hit when it was relaunched as a late show feature the year after its initial, unprofitable release. Even as Rocky Horror generated its own subcultural phenomenon, it contributed to the mainstreaming of the theatrical midnight movie.

Asian martial arts films began appearing as imports regularly during the 1970s. These "kung fu" films as they were often called, whatever martial art they featured, were popularized in the United States by the Hong Kong–produced movies of Bruce Lee and marketed to the same audience targeted by AIP and New World. Horror continued to attract young, independent American directors. As Roger Ebert explained in one 1974 review, "Horror and exploitation films almost always turn a profit if they're brought in at the right price. So they provide a good starting place for ambitious would-be filmmakers who can't get more conventional projects off the ground."[92] The movie under consideration was The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Made by Tobe Hooper for no more than $250,000, it earned $14.4 million in domestic rentals and become one of the most influential horror films of the decade.[93] John Carpenter's Halloween (1978), produced on a $320,000 budget, grossed over $80 million worldwide and effectively established the slasher flick as horror's primary mode for the next decade. Just as Hooper had learned from Romero's work, Halloween, in turn, largely followed the model of Black Christmas, directed by Deathdream's Bob Clark.[94]

On television, the parallels between the weekly series that became the mainstay of prime-time programming and the Hollywood series films of an earlier day had long been clear. In the 1970s, original feature-length programming increasingly began to echo the B movie as well. As production of TV movies expanded with the introduction of the ABC Movie of the Week in 1969, soon followed by the dedication of other network slots to original features, time and financial factors shifted the medium progressively into B-picture territory. Television films inspired by recent scandals—such as The Ordeal of Patty Hearst, which premiered a month after her release from prison in 1979—harkened all the way back to the 1920s and such movies as Human Wreckage and When Love Grows Cold, FBO pictures made swiftly in the wake of celebrity misfortunes. Many 1970s TV films—such as The California Kid (1974), starring Martin Sheen—were action-oriented genre pictures of a type familiar from contemporary cinematic B production. Nightmare in Badham County (1976), headed straight into the realm of road-tripping-girls-in-redneck-bondage exploitation.

The reverberations of Easy Rider could be felt in such pictures, as well as in a host of big-screen exploitation films. But its greatest influence on the fate of the B movie was less direct. By 1973, the major studios were catching on to the commercial potential of genres once largely consigned to the bargain basement. Rosemary's Baby had been a big hit, but it had little in common with the exploitation style. Warner Bros.' The Exorcist demonstrated that a heavily promoted horror film could be an absolute blockbuster: it was the biggest movie of the year and by far the highest-earning horror movie yet made. In William Paul's description, it is also "the film that really established gross-out as a mode of expression for mainstream cinema.... [P]ast exploitation films managed to exploit their cruelties by virtue of their marginality. The Exorcist made cruelty respectable. By the end of the decade, the exploitation booking strategy of opening films simultaneously in hundreds to thousands of theaters became standard industry practice."[95] Universal and writer-director George Lucas's American Graffiti did something similar. Described by Paul as "essentially an American-International teenybopper pic with a lot more spit and polish," it was 1973's third biggest film and, likewise, by far the highest-earning teen-themed movie yet made.[96] A-grade B movies of even greater historical import would follow in their wake.

Decline of the B (1): 1980s

Most of the B-movie production houses founded during the exploitation era collapsed or were subsumed by larger companies as the field's financial situation changed in the early 1980s. Even a comparatively cheap, efficiently made genre picture intended for theatrical release began to cost millions of dollars, as the major movie studios steadily moved into the production of expensive genre movies, raising audience expectations for spectacular action sequences and realistic special effects. Intimations of the trend were evident as early as Airport (1969) and especially in the mega-schlock of The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Earthquake (1973), and The Towering Inferno (1974). Their disaster plots and dialogue were B-grade at best; from an industry perspective, however, these were pictures firmly rooted in a tradition of star-stuffed extravaganzas. The Exorcist demonstrated the drawing power of big-budget, effects-laden horror. But the tidal shift in the majors' focus owed largely to the enormous success of three films: Steven Spielberg's creature feature Jaws (1975) and George Lucas's space opera Star Wars (1977) had each, in turn, become the highest-grossing film in motion picture history. Superman, released in December 1978, had proved that a studio could spend $55 million on a movie about a children's comic book character and turn a big profit—it was the biggest box-office hit of 1979.[97] Blockbuster fantasy spectacles like the original, 1933 King Kong had once been exceptional; in the new Hollywood, increasingly under the sway of multi-industrial conglomerates, they would rule.[98]

It had taken a decade and half, from 1961 to 1976, for the production cost of the average Hollywood feature to double from $2 million to $4 million—actually a decline if adjusted for inflation. In just four years it more than doubled again, hitting $8.5 million in 1980 (a constant-dollar increase of about 25 percent). Even as the U.S. inflation rate eased, the average expense of moviemaking would continue to soar.[100] With the majors now routinely saturation booking in over a thousand theaters, it was becoming increasingly difficult for smaller outfits to secure the exhibition commitments needed to turn a profit. Revival houses were now the almost-exclusive preserve of the double feature. One of the first leading casualties of the new economic regime was venerable B studio Allied Artists, which declared bankruptcy in April 1979.[101] In the late 1970s, AIP had moved into the production of relatively expensive comedies and genre films like the very successful Amityville Horror and the disastrous, $20 million Meteor in 1979. The studio was soon sold off and dissolved as a moviemaking concern by the end of 1980.[102]

Despite the mounting financial pressures, distribution obstacles, and overall risk, a substantial number of genre movies from small studios and independent filmmakers were still reaching theaters. Horror was the strongest low-budget genre of the time, particularly in the "slasher" mode as with The Slumber Party Massacre (1982), directed by Amy Holden-Jones and written by feminist author Rita Mae Brown. The film was produced for New World on a budget of $250,000.[103] At the beginning of 1983, Corman sold New World; New Horizons, later Concorde–New Horizons, became his primary company. In 1984, New Horizons released a critically applauded movie set amid the punk scene written and directed by Penelope Spheeris. The New York Times review concluded: "Suburbia is a good genre film."[104]

Larry Cohen continued to twist genre conventions in pictures such as Q (aka Q: The Winged Serpent; 1982): "the kind of movie that used to be indispensable to the market: an imaginative, popular, low-budget picture that makes the most of its limited resources, and in which people get on with the job instead of standing around talking about it."[105] In 1981, New Line put out Polyester, a John Waters movie with an estimated $300,000 budget and an old-school exploitation gimmick: Odorama. That October, a gore-filled yet stylish horror movie made for less than $400,000 debuted in Detroit.[106] The writer, director, and co–executive producer of The Book of the Dead, Sam Raimi, was a week shy of his twenty-second birthday; star and co–executive producer Bruce Campbell was twenty-three. "A shoestring tour de force,"[107] it was picked up for distribution by New Line, retitled The Evil Dead, and became a hit.

One of the most successful B-movie companies of the 1980s was a survivor from the heyday of the exploitation era, Troma Pictures, founded in 1974. Troma's most characteristic productions, including Class of Nuke 'Em High (1986), Redneck Zombies (1986), and Surf Nazis Must Die (1987), take exploitation for an absurdist spin. Troma's best-known production is The Toxic Avenger (1985); its hideous hero, affectionately known as Toxie, became the symbol of Troma and an icon of the 1980s B movie. One of the few successful B-studio startups of the decade was Rome-based Empire Pictures, whose first production, Ghoulies, reached theaters in 1985. The video rental market was also becoming central to B-film economics: Empire's financial model relied on seeing a profit not from theatrical rentals, but only later, at the video store.[108] A number of Concorde–New Horizon releases also went this route, appearing only briefly in theaters, if at all. The growth of the cable television industry also helped support the low-budget film industry, as many B movies quickly wound up as "filler" material for 24-hour cable channels or were made expressly for that purpose.

Decline of the B (2): 1990s

By 1990, the cost of the average U.S. film had passed $25 million.[109] Of the nine films released that year to gross more than $100 million at the U.S. box office, two would have been strictly B-movie material before the late 1970s: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Dick Tracy. Three more—the science-fiction thriller Total Recall, the action-filled detective thriller Die Hard 2, and the year's biggest hit, the slapstick kiddie comedy Home Alone—were also far closer to the traditional arena of the B's than to classic A-list subject matter.[110] The growing popularity of home video and access to unedited movies on cable and satellite television along with real estate pressures were making survival more difficult for the sort of small- or non-chain theaters that were the primary home of independently produced genre films. Drive-in screens were rapidly disappearing from the American landscape.

Surviving B-movie operations adapted in different ways. Releases from Troma now frequently went straight to video. New Line, in its first decade, had been almost exclusively a distributor of low-budget independent and foreign genre pictures. With the smash success of exploitation veteran Wes Craven's original Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), whose nearly $2 million cost it had directly backed, the company began moving steadily into higher-budget genre productions. In 1994, New Line was sold to the Turner Broadcasting System; it was soon being run as a midsized studio with a broad range of product alongside Warner Bros. within the Time Warner conglomerate. The following year, Showtime launched Roger Corman Presents, a series of thirteen straight-to-cable movies produced by Concorde–New Horizons. A New York Times reviewer found that the initial installment qualified as "vintage Corman...spiked with everything from bared female breasts to a mind-blowing quote from Thomas Mann's Death in Venice."[112]

At the same time as exhibition venues for B films vanished, the independent film movement was burgeoning; among the results were various crossovers between the low-budget genre movie and the "sophisticated" arthouse picture. Director Abel Ferrara, who built a reputation with violent B movies such as The Driller Killer (1979) and Ms. 45 (1981), made two works in the early nineties that marry exploitation-worthy depictions of sex, drugs, and general sleaze to complex examinations of honor and redemption: King of New York (1990) was backed by a group of mostly small production companies and the cost of Bad Lieutenant (1992), $1.8 million, was financed totally independently.[113] Larry Fessenden's micro-budget monster movies, such as No Telling (1991) and Habit (1997), reframe classic genre subjects—Frankenstein and vampirism, respectively—to explore issues of contemporary relevance. The budget of David Cronenberg's Crash (1996), $10 million, wasn't comfortably A-grade, but it was hardly B-level either. The film's imagery was another matter: "On its scandalizing surface, David Cronenberg's Crash suggests exploitation at its most disturbingly sick."[114] Financed, like King of New York, by a consortium of production companies, it was picked up for U.S. distribution by Fine Line Features. This result mirrored the film's scrambling of definitions: Fine Line was a subsidiary of New Line, recently merged into the Time Warner empire—specifically, it was the old exploitation distributor's arthouse division.

Transition II/The B movie in the digital age: 2000s

By the turn of the millennium, the average production cost of an American feature had already spent three years above the $50 million mark.[115] In 2005, the top ten movies at the U.S. box office included three adaptations of children's fantasy novels (including one extending and another initiating a series), a child-targeted cartoon, a comic book adaptation, a sci-fi series installment, a sci-fi remake, and a King Kong remake.[116] It was a slow year for Corman: he produced just one movie, which had no American theatrical release, true of most of the pictures he had been involved in recently. As big-budget Hollywood movies further usurped traditional B genres, the ongoing viability of the familiar brand of B movie was in grave doubt. Critic A. O. Scott of the New York Times warned of the impending "extinction" of

the cheesy, campy, guilty pleasures that used to bubble up with some regularity out of the B-picture ooze of cut-rate genre entertainment. Those cherished bad movies—full of jerry-built effects, abominable acting, ludicrous story lines—once flickered with zesty crudity in drive-ins and grind houses across the land. B-picture genres—science fiction and comic-book fantasy in particular, but also kiddie cartoons and horror pictures—now dominate the A-list, commanding the largest budgets.... [F]or the most part, the schlock of the past has evolved into star-driven, heavily publicized, expensive mediocrities....[117]

On the other hand, recent industry trends suggest the reemergence of something that looks very like the traditional A-B split in major studio production, though with fewer "programmers" bridging the gap. According to a 2006 report by industry analyst Alfonso Marone, "The average budget for a Hollywood movie is currently around $60m, rising to $100m when the cost of marketing for domestic launch (USA only) is factored into the equation. However, we are now witnessing a polarisation of film budgets into two tiers: large productions ($120-150m) and niche features ($5-20m).... Fewer $30-70m releases are expected."[118] Fox launched a new subsidiary in 2006, Fox Atomic, to concentrate on teen-oriented genre films, mostly variations of horror. The genre focus is similar to that of Sony's Screen Gems division and the Weinsteins' Dimension Films, but the economic model is deliberately low-rent, at least by major studio standards. According to a Variety report, "Fox Atomic is staying at or below the $10 million mark for many of its movies. It's also encouraging filmmakers to shoot digitally—a cheaper process that results in a grittier, teen-friendly look. And forget about stars. Of Atomic's nine announced films, not one has a big-name."[119] In sum, this is an updated version of a Golden Age big studio B unit targeting a market very similar to the one Arkoff and Nicholson's AIP helped define in the 1950s.

In a development hinted at in this Variety piece, recent technological advances are greatly facilitating the production of truly low-budget motion pictures. Although there have always been economical means with which to shoot movies, including Super 8 and 16 mm film and video cameras recording onto analog videotape, these mediums could hardly rival the image quality of 35 mm film. The development and widespread usage of digital cameras and postproduction methods allow even low-budget filmmakers to produce films with excellent (and not necessarily "grittier") image quality and precise editing effects. As Marone observes, "the equipment budget (camera, support) required for shooting digital is approximately 1/10th that for film, significantly lowering the production budget for independent features. At the same time, over the past 2-3 years, the quality of digital filmmaking has improved dramatically."[120] Independent filmmakers, whether working in a genre or arthouse mode, continue to find it difficult to gain access to distribution channels, though so-called digital end-to-end methods of distribution offer new opportunities. In a similar way, Internet sites such as YouTube have opened up entirely new avenues for the presentation of low-budget motion pictures.

Associated terms

C movie

The C movie is the grade of motion picture at the low end of the B movie, or—in some taxonomies—simply below it.[121] In the 1980s, with the growth of cable television, the C grade began to be applied with increasing frequency to low-quality genre films used as filler programming for that market. The "C" in the term then does double duty, referring not only to quality that is lower than "B" but also to the initial c of cable. Helping to popularize the notion of the C movie was the successful TV series Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1988–99), which ran on national cable channels (first Comedy Central, then the Sci Fi Channel) after its first year; updating a concept introduced by TV hostess Vampira over three decades before, MST3K presented cheap, low-grade movies, primarily science fiction of the 1950s and 1960s, along with running voiceover commentary highlighting the films' shortcomings. Director Ed Wood has been called "the master of the 'C-movie'" in this sense, although the term Z movie (see below) is perhaps even more applicable to his work.[122] The rapid expansion of niche cable and satellite outlets such as Sci Fi (with its Sci Fi Pictures) and HBO's genre channels in the 1990s and 2000s has meant an ongoing market for contemporary C pictures, many of them "direct to cable" movies—modestly budgeted genre films never released in theaters.[123]

Z movie

The term Z movie (or grade-Z movie) arose in the mid-1960s as an informal description of certain unequivocally non-A films. It was soon adopted to characterize low-budget pictures with quality standards well below those of most B and even C movies.[124] While B movies may have mediocre scripts and actors who are relatively unknown or past their prime, they are for the most part competently lit, shot, and edited. The economizing shortcuts of films identified as C movies tend to be evident throughout; nonetheless, C movies are the products of relatively stable entities within the commercial film industry and thus still adhere to certain production norms.

In contrast, most films referred to as Z movies are made on very small budgets by operations on the fringes of the industry. As a result, scripts are often laughably bad, continuity errors tend to arise during shooting, and nonprofessional actors are frequently cast. Many Z movies are also poorly lit and edited. The micro-budget "quickies" of 1930s fly-by-night Poverty Row production houses may be thought of as Z movies avant la lettre.[125] Latter-day Z's are often characterized by violent, gory, and/or sexual content and a minimum of artistic interest—much of this product is destined for the subscription TV equivalent of the grind house.

Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959), directed by Ed Wood, is frequently cited as exemplifying the Z movie: It features an incoherent plot, bizarre dialogue, inept acting, intrusive narration, the cheapest conceivable special effects, and cardboard sets that the actors occasionally bump into and knock over. Stock footage is used throughout, entire passages appear multiple times, and boom mics are visible. Outdoor scenes include both day and night shots in the same sequence. The movie stars Maila Nurmi, in her Vampira persona, and Bela Lugosi, who died before the film was made. Test footage of Lugosi taken for another project is intercut with shots of a double with a different physique and hair color—he holds a cape over his face in every scene.[126]

Psychotronic movie

Psychotronic movie is a term coined by film critic Michael J. Weldon—referred to by a fellow critic as "the historian of marginal movies"—to denote the sort of low-budget genre pictures that are generally disdained or ignored entirely by the critical establishment.[127] Weldon's immediate source for the term was the Chicago cult film The Psychotronic Man (1980), whose titular character is a barber who develops the bizarre ability to kill using psychic energy.[128] According to Weldon, “My original idea with that word is that it’s a two-part word. 'Psycho' stands for the horror movies, and 'tronic' stands for the science fiction movies. I very quickly expanded the meaning of the word to include any kind of exploitation or B-movie.”[129] The term, popularized beginning in the 1980s with publications of Weldon's such as The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film and Psychotronic Video magazine, has subsequently been adopted by other critics and fans. Use of the term tends to emphasize a focus on and affection for those B movies that lend themselves to appreciation as camp.[130]

See also

Notes

- ^ Hirschhorn (1999), pp. 9–10, 17.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36; Balio (1995), p. 29.

- ^ See, e.g., Taves (1995), p. 320.

- ^ Balio (1995), p. 29. See also Schatz (1999), pp. 16, 324.

- ^ Steve Broidy, president of Monogram/Allied Artists, quoted in Schatz (1999), p. 75.

- ^ Taves (1995), pp. 326–327.

- ^ See, e.g., Balio (1995), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Epstein (2005), p. 6. See also Schatz (1999), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 325.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 326.

- ^ Epstein (2005), p. 4.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 317. Taves (like this article) adopts the usage of "programmer" argued for by author Don Miller in his 1973 study B Movies (New York: Ballantine). As Taves notes, "the term programmer was used in a variety of different ways by reviewers" of the 1930s (p. 431, n. 8). Some present-day critics employ the Miller–Taves usage; others refer to any B movie from the Golden Age as a "programmer" or "program picture."

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 325.

- ^ Balio (1995), p. 102.

- ^ See Taves (1995), pp. 321–329.

- ^ Adapted from Finler (1988), pp. 21–22.

- ^ In operation from 1936 to 1940, Grand National was something like the United Artists of Poverty Row. Most of the films it released were the work of independent producers; in its peak year, 1937, Grand National did produce approximately twenty pictures of its own. See Taves (1995), p. 323; McCarthy and Flynn (1975), p. 20.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 313.

- ^ Nachbar (1974), p. 2.

- ^ Tuska (1974), p. 37.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 327–328.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 316.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 318.

- ^ Quoted in Schatz (1999), p. 75.

- ^ Naremore (1998), p. 141.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 328.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 73.

- ^ Schatz (1999), pp. 19–21, 45, 72, 160–163. See also Taves (1995), pp. 314–315.

- ^ Quoted in Schatz (1999), p. 175.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 16.

- ^ Jewell (1982), 181; Lasky (1989), 184–185.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 78.

- ^ Schatz (1999), pp. 340–341.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 295; Naremore (1998), p. 142; PRC (Producers Releasing Corporation) essay by Mike Haberfelner, August 2005; part of the (re)Search my Trash website. Retrieved 12/30/06.

- ^ Robert Smith, "Mann in the Dark," quoted in Ottoson (1981), p. 145.

- ^ See, e.g., Dave Kehr, "Critic's Choice: New DVD's," New York Times, August 22, 2006; Dave Kehr, "Critic's Choice: New DVD's," New York Times, June 7, 2005; Robert Sklar, "Film Noir Lite: When Actions Have No Consequences," New York Times, "Week in Review," June 2, 2002.

- ^ For a detailed consideration of classic B noir, see Arthur Lyons, Death on the Cheap: The Lost B Movies of Film Noir (New York: Da Capo, 2000).

- ^ Jewell (1982), p. 147.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 175.

- ^ Naremore (1998), p. 144.

- ^ Strawn (1974), p. 257.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36.

- ^ Lev (2003), p. 205.

- ^ Lasky (1989), p. 229.

- ^ See Finler (1988), pp. 276–277, for top films. Finler lists The Country Girl as 1955, when it made most of its money, but it premiered in December 1954. The Seven Year Itch replaces it in this analysis (the two films happen to be virtually identical in length).

- ^ See, e.g., Eddie Muller, Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir (New York: St. Martin's, 1998), p. 176.

- ^ Maltby (2000).

- ^ Shapiro (2002), p. 96. See also Atomic Films: The CONELRAD 100 part of the CONELRAD website.

- ^ Lev (2003), pp. 186, 184; Braucort (1972), 75.

- ^ Auty (1999), p. 24. See also Shapiro (2002), pp. 120–124.

- ^ Strawn (1974), p. 259; Lev (2003), p. 206.

- ^ Cook (2000), p. 324. See also p. 171.

- ^ Di Franco (1979), p. 3.

- ^ Corman (1998), p. 36. In fact, it appears that Corman made at least one true B picture—according to Arkoff, Apache Woman, to his displeasure, was handled as a second feature (Strawn [1974], p. 258).

- ^ Heffernan (2004), pp. 102–104.

- ^ Heffernan (2004), pp. 95–98.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 15.

- ^ Cook (2000), p. 324.

- ^ Nason (1959).

- ^ Hirschhorn (1979), p. 343.

- ^ Cook (2000), p. 324.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36.

- ^ Thompson (1960).

- ^ Quoted in Di Franco (1979), p. 97.

- ^ Per Corman, quoted in Di Franco (1979), p. 97.

- ^ Quoted in Reid (2005a), p. 5.

- ^ Archer (1960).

- ^ Schaefer (1999), pp. 187, 376.

- ^ Schaefer (1999), p. 118.

- ^ Something Weird Traveling Roadshow Films review of DVD release with historical analysis by Bill Gibron, July 24, 2003; part of the DVD Verdict website. Retrieved 11/17/06.

- ^ Halperin (2006), p. 201.

- ^ Halperin (2006), p. 201.

- ^ Cook (2000), p. 222.

- ^ Paul (1994), p. 33.

- ^ Rockoff (2002), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Cook (2000), pp. 222–223.

- ^ Cook (2000), p. 223.

- ^ Canby (1969).

- ^ Quote: Cagin and Dray (1984), p. 53. General history: Cagin and Dray (1984), pp. 61–66. Financial figures: per associate producer William L. Hayward, cited in Biskind (1998), p. 74.

- ^ See Finler (1988), p. 277, for top films. Finler lists Hello, Dolly! as 1970, when it made most of its money, but it premiered in December 1969. The Owl and the Pussycat, 51 minutes shorter, replaces it in this analysis.

- ^ From 1955: Apache Woman, The Beast with a Million Eyes, Day the World Ended, The Fast and the Furious, and Five Guns West. From 1970: Angels Die Hard, Bloody Mama, The Dunwich Horror, Ivanna (aka Scream of the Demon Lover; U.S. premiere: 1971), and The Student Nurses. For purchase of Ivanna: Di Franco (1979), p. 164.

- ^ Di Franco (1979), p. 160

- ^ Kael (1976), p. 269.

- ^ Puchalski (2002), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Van Peebles (2003).

- ^ Quoted in Reynaud (2006). See Reynaud also for Loden's fundraising efforts. For production cost: Schickel (2005), p. 432. See also "For Wanda" essay by Bérénice Reynaud, 2002 (1995); part of the Sense of Cinema website. Retrieved 12/29/06.

- ^ See, e.g., Tom Milne, "Electra Glide in Blue," in Time Out Film Guide, 8th ed., ed. John Pym (London et al.: Penguin, 1999), p. 303.

- ^ Greenspun (1973).

- ^ See, e.g., Jack Stevenson, Land of a Thousand Balconies: Discoveries and Confessions of a B-Movie Archaeologist (Manchester: Headpress/Critical Vision, 2003), pp. 49–50; Joanne Hollows, "The Masculinity of Cult," in Defining Cult Movies: The Cultural Politics of Oppositional Taste, ed. Mark Jancovich (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2003), pp. 35–53; Janet Staiger, Blockbuster TV: Must-see Sitcoms in the Network Era (New York and London: New York University Press, 2000), p. 112.

- ^ Ebert (1974).

- ^ For the film's cost: Rockoff (2002), p. 42. For its U.S. rentals: Cook (2000), p. 229. For its influence: Sapolsky and Molitor (1996), p. 36; Rubin (1999), p. 155.

- ^ For the film's cost and worldwide gross: Harper (2004), pp. 12–13. For its influence and debt to Black Christmas: Rockoff (2002); Paul (1994), p. 320.

- ^ Paul (1994), pp. 288, 291.

- ^ Paul (1994), p. 92.

- ^ Superman (1978) part of Box Office Mojo website. Retrieved 12/29/06.

- ^ See The eight majors in the post-system era for a record of the sales and mergers involving the eight major studios of the Golden Age.

- ^ David Handelman ("The Brothers from Another Planet," Rolling Stone, May 21, 1987), quoted in Russell (2001), p. 7.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36. Prince (2002) gives $9 million as the average production cost in 1980, and a total of $13 million after adding on costs for manufacturing exhibition prints and marketing (p. 20). See also p. 21, chart 1.2. The Box Office Mojo website gives $9.4 million as the 1980 production figure; see Movie Box Office Results by Year, 1980–Present. Retrieved 12/29/06.

- ^ Lubasch (1979).

- ^ Cook (2000), pp. 323–324.

- ^ Collum (2004), pp. 11–14.

- ^ Canby (1984). Note that IMDb.com's entry on the film incorrectly states that it was released by New World.

- ^ Petit (1999), p. 1172.

- ^ Cost per Bruce Campbell, cited in Warren (2001), p. 45

- ^ David Chute (Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, May 27, 1983), quoted in Warren (2001), p. 94.

- ^ Morrow (1996), p. 112.