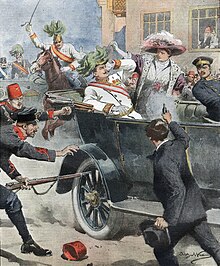

Assassination attempt in Sarajevo

During the assassination attempt in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 , the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie Chotek, Duchess of Hohenberg , were attacked by Gavrilo Princip , a member of the Serbian nationalist movement Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia) , during their visit to Sarajevo. , murdered. The assassination attempt in the Bosnian capital planned by the Serbian secret society “ Black Hand ” triggered the July crisis , which ultimately led to the First World War .

prehistory

Schedule the visit

Archduke Franz Ferdinand went to Sarajevo from a meeting with the German Emperor Wilhelm II at his country residence at Konopischt Castle in Beneschau ( Bohemia ) in order to complete the maneuvers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. and XVI. Corps in Bosnia to attend. The visit was scheduled for June 28th at the request of the Austro-Hungarian governor of Bosnia-Herzegovina , Feldzeugmeister Oskar Potiorek .

However, the assassins had been planning the attack since March 1914 because newspapers had announced Franz Ferdinand's visit without specifying the date. It was particularly important for the assassins to carry out an assassination attempt during Franz Ferdinand's visit, although the deeper meaning of June 28 was probably just a side effect.

On that day, Vidovdan coincided with the 525th anniversary of the Battle of the Blackbird Field - a symbolic date for many Serbs . According to a letter from the secretary of the Austro-Hungarian legation in Belgrade, Ritter von Storck, to Foreign Minister Count Leopold Berchtold on June 29, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian authorities must be informed about the extent of the extensive events planned months in advance in the Kingdom of Serbia for the 525th Celebration of the lost battle have been very knowledgeable.

On the one hand, early summer was a common season for maneuvers, and a visit to a maneuver was a good idea, since the heir to the throne had been making such troop visits in place of the emperor as Inspector General since 1909. Potiorek wanted to maintain the reputation of the Danube Monarchy , which had not been very high since the Bosnian annexation crisis of 1908, with a visit from the heir to the throne, to which a targeted provocation would hardly have contributed. The Finance Minister responsible for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Leon Ritter von Biliński , never objected to the visit because, according to him, the original plan approved by the Emperor did not include a visit to the city.

On the other hand, a possible provocation by the wing of government circles in the Danube Monarchy, which is striving for war, cannot be ruled out. Biliński mentions in his memoirs that Potiorek harbored a deep aversion to Serbs, which would have massively hampered Austria-Hungary's Bosnian policy and the consensus with the Bosnian Serbs. According to Biliński, the original plan approved by Emperor Franz Joseph I only provided for a visit to the troop maneuvers. The decision to visit the city, and in particular the Duchess's participation, was made at short notice and without Biliński's participation. Biliński also mentions that his ministry was the only office in Austria-Hungary that was expressly omitted from the distribution list for the heir apparent's visit plans so as not to “hinder the efforts of the head of the country to receive a worthy guest”.

Earlier attacks on high-ranking representatives of the dual monarchy, such as the attack on governor Marijan Freiherr Varešanin von Vareš on June 15, 1910 in Sarajevo, had failed, and the assassins would probably have chosen another, less symbolic date.

"Only in the interpretation of posterity and above all in the elaboration of the particular determination and symbolism did it then come about that ... June 28, the Vidovdan (St. Vitus's Day), the anniversary of the Serbian defeat against the Ottomans on the Amselfeld in 1389, as special Provocation has been put down. But here, too, chance reigned and not long-term or even subtle planning. Because when you set the time for the maneuvers of the XVI. Corps determined, only the season, the level of training of the troops and the exercise acceptance were decisive. "

But it is also argued that in Vienna in particular the Vidovdan should actually have been sufficiently known as the “holy day” of the Serbs. The visit to the recently annexed province on that day, even if it was not intended as a provocation, could therefore in fact have been viewed as a special humiliation - or, on the contrary, as a particularly attractive opportunity to strike against foreign rule.

The day before, Sophie von Hohenberg sent a telegram to a friend expressing her well-being. It is now archived in the Bautzen diocesan archive.

Warnings

Attacks had taken place in Sarajevo before. The student Bogdan Žerajić had planned an assassination attempt on Emperor Franz Joseph in 1910, but refrained from doing so due to the old age of the monarch. Instead, he shot the Bosnian governor, General Marijan Freiherr Varešanin von Vareš at the opening of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian state parliament on June 15, 1910 , but missed him, whereupon he killed himself with a head shot. Žerajić became the model for Princip: he is said to have solemnly sworn at Žerajić's grave to avenge him.

Even after vague warnings, Archduke Franz Ferdinand did not let himself be deterred from traveling to Sarajevo. “Under a glass lintel”, he had said on another occasion, “I will not allow myself to be placed. We are always in mortal danger. You just have to trust in God. ”Since no one expected any danger, the safety precautions were correspondingly low. The schedule and route were published in the newspapers weeks before the visit, probably also to attract as many cheering spectators as possible. Warnings were issued before almost every visit, and not just in relation to Bosnia. However, none of the warners had become so clear that the extent of the danger could really have been deduced from it.

Since the Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, according to a later testimony of the then cabinet member Ljuba Jovanović, allegedly found out about the murder plan in advance, probably from his spy in the "black hand", Milan Ciganović (Pašić always denied this), he was after Christopher's account Clark in a dilemma . If he let the plan come to fruition, he risked a war with Austria-Hungary because of the connection to the secret organization “Ujedinjenje ili Smrt” (“Unification or Death” or “ Black Hand ”); if he betrayed the plan, he risked being portrayed as a traitor by his countrymen. He allegedly entrusted Jovan Jovanović, the Serbian envoy in Vienna, with the task of warning Austria-Hungary of the attack with vague diplomatic statements. Jovanović, who was considered a nationalist and rarely received a warm welcome in Vienna, confided in a conversation to the kuk Finance Minister von Biliński , who is known to be open and sociable , that it would be good and sensible if Franz Ferdinand did not travel to Sarajevo, because otherwise “some young Serb take a sharp bullet instead of a blank cartridge and shoot it ”. Biliński replied with a laugh, “let's hope that something like this never happens” and kept the content of the conversation to himself. The authenticity of this portrayal of Clark and the content of the conversation is, however, uncertain, since the conversation was only portrayed in this way by Jovanović ten years later. On July 4, 1914, when Pašić asked for this, Jovanović only reported to Belgrade that he had talked to some ambassadors in general about the provocation by the maneuvers.

According to Christopher Clark , some warning was given, but not one appropriate to the situation. The official security measures did not meet the standards, so that the usual cordon of soldiers was missing and the bodyguard was left behind at the station due to a misunderstanding.

Jörn Leonhard , on the other hand, judges that "[t] he report by Count Harrach [...] on June 28, 1914 [...] reveals a barely comprehensible degree of naivety on the part of the authorities".

Preparations for the attack

Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević , known as Apis, head of the Serbian military secret service and leading figure of the “Black Hand”, was the main figure behind the plot to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand, but the idea probably came from his comrade Rade Malobabić . As part of this conspiracy, the former vigilante Voja Tankosić recruited the core of the commando sent to Bosnia, the three members of the pro-Serb Bosnian youth organization Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia): Gavrilo Princip , a 19-year-old high school student, Nedeljko Čabrinović, a 19-year-old printer, and Trifun “Trifko” Grabež, an 18-year-old dropout. The Serbian head of government had neither ordered the assassination attempt, nor was the government directly involved, but the Serbian prime minister as well as several ministers and the military knew about individual events of the conspiracy. According to the American historian Sean McMeekin , the Russian military attaché in Belgrade, General Viktor Artamonov, who was in virtually daily contact with the intelligence chief Dimitrijević, and the Russian ambassador Nikolai Hartwig were privy to the assassination plans.

Once the planning of the attack began in earnest, care was taken to ensure that there were no obvious links between the cell and the Belgrade authorities. The executive officer of the assassins was Milan Ciganović , who was subordinate to Tankosić or, through this, Dimitrijević. All orders were passed on orally. The tacit consent between the Serbian state and the networks involved in the conspiracy was deliberately secret and informal in nature.

Gavrilo Princip himself made the decision to kill Franz Ferdinand in the spring of 1914 in Belgrade at the grave of Bogdan Žerajić, after reading a report about his announced visit in an Austrian newspaper. According to other accounts, the real originator of the idea was Nedeljko Čabrinović, who was made aware of the upcoming visit by a newspaper clipping from a friend, the journalist Mihajlo Pušara. At that time the visit was still uncertain because of a serious illness of Emperor Franz Joseph I.

The assassins saw some personalities as worthwhile targets: the Austrian Emperor, Foreign Minister Berchtold , Finance Minister Biliński , Feldzeugmeister Potiorek , the Banus of Croatia Ivan Skerlecz, the Governor of Dalmatia Slavko Cuvaj, and of course Franz Ferdinand. According to Princip, Franz Ferdinand was not selected because of alleged hostility towards the Serbs, but because “as the future ruler he would have carried out certain ideas and reforms that stood in our way.” Princip informed Čabrinović and Grabež of his intentions and secured theirs Support. Since Princip was unable to implement the plan without outside help, he contacted Milan Ciganović, a Serbian secret service agent and well-known folk hero who worked as a railroad clerk and lived in the same house. Ciganović was in contact with Major Vojin P. Tankošić, who Princip already knew from his unsuccessful attempt in 1912 to volunteer in the Balkan Wars . Princip neither knew that Ciganović and Tankošić were leading members of the "Black Hand", nor was Princip, who was apparently thinking of a local project himself, informed about the background to the conspiracy.

Ciganović gave the militarily inexperienced young people in the Belgrade Park Topčider shooting lessons, with Princip being the best shooter, and on May 27, 1914 handed them four pistols with ammunition and six bombs from the Serbian army. The origin of the weapons could never be fully clarified because many Serb militia members owned such weapons. They also received some money for travel expenses and cyanide bottles to kill themselves after the attack.

One month before the attack, the three attackers traveled to Sarajevo via Tuzla . Ciganović helped them, with the help of Miško Jovanović, to bring the weapons unnoticed across the Bosnian border. In Tuzla they were joined as the fourth member Danilo Ilić, a 23-year-old teacher. Ilić recruited three more members of Mlada Bosna, the two high school students Vaso Čubrilović (17 years old) and Cvetko Popović (18 years old) as well as Muhamed Mehmedbašić, a 27-year-old Muslim Bosnian who was a carpenter. The real purpose of this second Sarajevo cell was to cover up the traces of the conspiracy.

Other members of Mlada Bosna who did not appear directly or armed were also involved in the conspiracy: Veljko Čubrilović, Vaso's brother and teacher from Priboj, Miško Jovanović, businessman and bank director from Tuzla, Mladen Stojaković, doctor and later a folk hero in the Second World War , his brother Sreten, sculptor; Jezdimir Dangić, Lieutenant Colonel of the Gendarmerie and later Chetnik - Vojwode , Mitar Kerović and his son Neđa, and finally Jakov Milović, a farmer from Eastern Bosnia.

Some of the group of assassins withdrew at the last moment because murder was unsuitable for protesting. But the younger assassins wanted to carry out the plan anyway.

The assassins positioned themselves on the Appel quay (today: Obala Kulina bana) along the Miljacka river. Mehmedbašić and Čabrinović were to act as the first and took up position west of the Ćumurija Bridge, while the other five assassins positioned themselves as reserves up to the Kaiser Bridge (today: Careva Čuprija). According to the Museum of Sarajevo , Mehmedbašić stood west of the first confluence of Ćumurija Street (forked confluence), Čabrinović east, both on the river side. Čubrilović and Popović stood a few meters further east on both sides of the road in front of the second confluence of Ćumurija Street and at the Ćumurija Bridge. Princip positioned himself on the river side shortly before the Latin bridge , across the way he later carried out the second, then “successful” attack. Grabež stood on the river side, west of the Kaiser Bridge, opposite the current confluence of Bazardžani Street. Ilić shuttled unarmed between the groups of assassins.

First stop

During the visit, the couple heir to the throne resided in Ilidža , a seaside resort about 12 kilometers west of Sarajevo. On June 28, 1914, they traveled by train from Ilidža to the city's western border, where there was a tobacco factory, which was a frequent departure point for Austro-Hungarian dignitaries to visit Sarajevo. According to Biliński, who bases his memories on a report from Archducal Marshal Colonel Count Rumerskirch to Minister of War Alexander Ritter von Krobatin , the security precautions were particularly low, which was in contrast to the comparatively strict precautions when Franz Joseph I visited Sarajevo in 1910. The policemen and secret policemen who should have gone ahead of the column were not equipped with cars or carriages for this purpose and were therefore heavily loaded with the Duchess's jewelery chests and stayed at the tobacco factory.

According to Biliński, the arrival of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was announced to the minute, which made it easier to carry out the attack. Before the departure, the police captain Gerde, a Hungarian, informed the regional chief Potiorek that he was not able to take care of the safety of the passengers on the long distance from the tobacco factory to the town hall with a number of 30 to 40 police officers. and therefore need support from military units. Potiorek replied that because no military was stationed in the city due to the maneuvers, it could not arrive in time. Thereupon the chief of the Bosnian gendarmerie, General Šnjarić, proposed to set up a gendarmerie cordon along the route, but Potiorek also rejected this suggestion.

Franz Ferdinand and his wife drove in a column of six cars (plus the police car in front) on the Appel quay (today: Obala Kulina bana) along the Miljacka river to the town hall of Sarajevo . In the first vehicle sat the mayor, Efendi Fehim Čurčić , and the police chief Dr. Gerde. In the second vehicle, a double phaeton (28/32 hp) from Graef & Stift , sat Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, across from them, Head of State Potiorek. In the front sat the chauffeur Leopold Lojka and Franz Graf Harrach , the owner of the car. In the third vehicle sat Sophie's chambermaid, Alexander Graf von Boos zu Waldeck and the wing adjutant of the country chief, Lieutenant Colonel Merizzi, who drove the car. In the fourth and fifth vehicles sat, among others, Baron Morsey , Colonel Bardolff , the head of the archducal military chancellery, court marshal Rumerskirch and Bosnian officials like the government councilor Starch. The sixth vehicle was empty and was carried as a reserve.

Around ten o'clock the column drove past Mehmedbašić, who was supposed to drop a bomb but did nothing. He later explained his inactivity by stating that Ilić had instructed him not to drop the bomb unless he recognized the heir to the throne's car. But he did not succeed in doing this. One of the next assassins on the route, Čabrinović, stood across from Café Mostar (today property Ćumurija 1), where the also idle Čubrilović was sitting, and asked a police officer in which vehicle the Archduke was sitting. When he gave him the correct answer, he knocked off the fuse on his bomb on a tram pole west of the Ćumurija bridge and threw it in the direction of the car. The driver noticed the flying dark object and accelerated, while Franz Ferdinand raised his arm to protect his wife. The bomb ricocheted off Franz Ferdinand's arm, fell back over the roof of the car, and exploded shortly before the third automobile, injuring Lieutenant Colonel Merizzi and Count Boos-Waldeck, as well as half a dozen onlookers.

According to Clark, Čabrinović swallowed the cyanide provided by the Black Hand and jumped into the Miljacka. However, the poison was old and ineffective, so he just vomited. According to his own account, he spilled the powder in the excitement. In addition, the river was not very deep at the point in question. Čabrinović was caught by the crowd, almost lynched, and arrested. In view of this, the assassin Gavrilo Princip now went into hiding in the crowd, sat down in a coffee house and considered shooting and killing his chosen accomplice in order to avoid arrest.

After Lieutenant Colonel Merizzi was only slightly injured according to initial information and had been taken to the garrison hospital, Franz Ferdinand ordered that the journey be continued. On the way to the town hall, the column drove past the other assassins, but they did nothing. Vaso Čubrilović later testified that he did not shoot because he felt sorry for the Duchess, Cvetko Popović testified that he was afraid and at that moment did not know what was happening to him.

When he arrived at the town hall, the mayor started a prepared welcoming speech in front of many local dignitaries, but was immediately interrupted by Franz Ferdinand: “Mayor, you come to Sarajevo to visit and are bombed! That's outrageous. ”But he was finally able to calm down. After his visit to the town hall, he ordered a change of route. He did not want to go directly to the Bosnian-Hercegovinian State Museum (where the Serbian historian Vladimir Ćorović was waiting for his arrival) as planned, but also to visit Merizzi, who was injured in the neck in the attack by Čabrinović, in the hospital.

Unfortunately, the hospital was at the other end of town. According to Biliński, Rumerskirch reported that Franz Ferdinand, worried about his wife, consulted Potiorek and Gerde after his stay at the town hall about whether it was sensible to go there in view of the bombing. The alternative was to take a different road back to Ilidža or straight to the Konak , which was a few minutes' drive from the town hall. While Gerde hesitated, Potiorek is said to have exclaimed: "Your Imperial Highness can go on, I will take responsibility for it".

Second attack

Contrary to the instructions, the motorcade turned into the originally planned route at the level of the Latin bridge leading over the Miljacka and also cut the curve (left-hand traffic at the time) so that the distance to Princip was only a good two meters. Lojka, who was not sufficiently oriented about the new route (moreover, the two cars in front had also turned wrongly), put the car in reverse to get back onto the quay; the vehicle stood still for a few seconds. To his great surprise, Princip saw the car with the Archduke stop in front of the Moritz Schiller delicatessen, where he was having a coffee at a table in the street. He got up, stepped out into the street, pulled out his pistol, a 9 mm FN Browning model 1910 pistol made by the Belgian company Fabrique Nationale with serial number 19074, and shot Franz Ferdinand and his wife twice from a few meters away.

The first projectile penetrated the vehicle wall, causing the projectile to deform, become sharp-edged and begin to rotate. Then it hit Sophie in the abdomen and inflicted a number of injuries there, from which she bled to death within a very short time while still in the car itself. When Franz Ferdinand noticed that his wife had been hit, he allegedly called out: “Sopherl! Sopherl! Do not die! Stay alive for our children! ”Immediately afterwards the second shot was fired, which hit Franz Ferdinand in the neck, tore his jugular vein and injured his windpipe. Count Harrach , who stood on the left step as protection , turned around, grabbed the heir to the throne by the shoulder and shouted: "Your Majesty, what is it?", Whereupon Franz Ferdinand replied: "It is nothing ..." and a moment later passed out . The heir to the throne was not bleeding from the bullet wound itself, but mainly through the injured windpipe, which in turn was fed by the injured jugular vein. That is also the reason why the uniform of the heir to the throne has large traces of blood on the front.

Princip immediately swallowed his potassium cyanide, but vomited it, whereupon he tried to shoot himself with the pistol. However, the pistol was torn from his hand and the angry crowd tried to lynch him. While Princip was immediately arrested by the gendarmes, beaten with sabers and taken away, the driver turned around and drove quickly to Potiorek's residence, the Konak . There, first responders quickly called in frantically tried to save the life of the heir to the throne, cutting off his uniform in several places in a desperate effort to stop the flow of blood, which however did not succeed. Franz Ferdinand succumbed to his injuries shortly afterwards in the Konak.

Princip later testified that he did not want to hit Sophie at all, the shots were aimed at Franz Ferdinand and Potiorek.

Reactions to the attack

The death of the heir to the throne did not trigger general mourning in Austria-Hungary. The envoy in Bucharest and later Foreign Minister Ottokar Graf Czernin later recalled that there were more happy people than mourners in Vienna and Budapest. Franz Ferdinand and his confidants, often referred to as the “ Belvedere Bagage” in conservative Viennese circles , had enemies not only there. His plans for a trialist imperial constitution with special consideration of the Croats met with categorical rejection, especially in the Hungarian part of the empire.

The conspiracy theory was spread in völkisch and German national circles, especially with the journalist Friedrich Wichtl , that behind the attack were in truth Freemasons and Jews who wanted to get closer to their alleged goal of world domination .

Political consequences of the attack

At first, even at the Viennese court, it was not believed that the Serbian government was complicit in the assassination attempt on the Archduke. The Austro-Hungarian Section Councilor Friedrich Wiesner led the investigation and wrote in his report of July 13, 1914 to the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry:

“The Serbian government was also involved in the conduct of the assassination attempt or its preparation and provision of weapons by nothing proven or even suspected. Rather, there are indications that this is to be regarded as excluded. By testimony of the accused, it was established that the assassination attempt in Belgrade was decided and prepared with the assistance of Serbian state officials Ciganović 'and Major Tankošic', both of whom provided bombs, Brownings, ammunition and cyanide. "

In contrast, after the war, Wiesner argued that the Serbian government was complicit.

The assassination attempt in Sarajevo was finally used by Austria-Hungary, after some hesitation on the part of the Hofburg and after consultations in Berlin, as a justification for an initially regionally planned military attack against Serbia. In the government in Vienna there was initially a "peace party" and a "war party" facing each other. With the death of Franz Ferdinand, the “Peace Party” had lost one of its most important advocates; as a representative of the "war party", Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf had been pushing for military action against Serbia since 1907. Count Berchtold, the emperor and the Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza remained undecided for the time being.

The Serbian government was aware of the wait-and-see attitude of the Viennese court and was aware of the possible consequences. She regretted the incident, denied any connection with the attack and pointed out that all perpetrators came from annexed Bosnia and were formally Austrians. In addition, there is no evidence to suggest any official Serbian involvement. On the other hand, in Austria-Hungary the Serbian organization Narodna Odbrana (People's Defense) was officially designated as the instigator of the attack.

Austria-Hungary also clashed with the critical Serbian press, which was viewed as hostile, and blamed them for the heated political mood that favored the murder of the heir to the Austrian throne. Serbia, on the other hand, relied on the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of the press for private media and saw the officially controlled and nationalist Austro-Hungarian press (especially the conservative “ Reichspost ”) as the real source of problems.

In its indecision, Austria-Hungary sought support from Germany. The decision to strike against Serbia on July 5, 1914 was made during the “ Mission Hoyos ” in Potsdam , specifically also in the event that “serious European complications” should arise from it. On July 6, 1914, Germany assured Austria-Hungary by telegram that it would fully support the action against Serbia, thereby issuing a " blank check ". Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey also promised in good time that they would side with the Triple Alliance if Austria-Hungary should decide to “teach Serbia a lesson”.

Berchtold instructed the Austrian envoy in Belgrade the following day:

“However the Serbs react - you have to cut off relations and leave; there has to be a war. "

On July 8, 1914, Berchtold expressed concern that a “weak attitude could discredit our position towards Germany”. At its meeting on July 19, the Council of Ministers left open whether Serbia - as the diplomat Count Alexander Hoyos considered - should be divided between other Balkan states. Count Tisza only agreed to the sending of an ultimatum because no or only small strategically important relinquishment of territory was required from Serbia.

Vienna was now determined to go to war and not interested in a Serbian relent:

"It was agreed that the request note should be sent to Serbia at the earliest possible point in time and that it should be edited in such a way that Belgrade had to reject it."

On July 23, 1914, Austria-Hungary presented Serbia with an extremely sharp ultimatum limited to 48 hours . Officially, this was a demarche , because initially it was not threatened directly with war, but only with a break in diplomatic relations. In the note, Serbia was asked to condemn all efforts aimed at the separation of Austro-Hungarian territory and to proceed against this with the utmost severity in the future. Among other things, Serbia should suppress all anti-Austrian propaganda , take immediate steps against Narodna Obrana , remove those involved in the attack from the civil service and, above all, have

“To agree that in Serbia organs of the Austro-Hungarian government cooperate in the suppression of the subversive movement directed against the territorial integrity of the monarchy ... to initiate a judicial investigation against those participants in the plot of June 28 who are on Serbian territory; from the k. and k. Bodies delegated to the government will take part in the relevant surveys ... "

In response to the ultimatum, the Council of Ministers of Russia issued a memorandum to Serbia on July 24, 1914, promising that Russia would lobby the major European powers to postpone the ultimatum in order to give them the "opportunity to conduct a detailed investigation into the assassination attempt in Sarajevo." to offer. Russia also announced that it would mobilize its troops and withdraw its financial resources from Germany and Austria, and promised that it would not remain inactive in the event of an Austro-Hungarian attack on Serbia.

Serbia unconditionally accepted most of the ultimatum, but made the following statement on point 6:

“The royal government naturally considers it its duty to initiate an investigation against all those persons who were involved in the plot of 15/28. June were or should have been involved and who are in their field. As far as the participation of organs of the Austro-Hungarian government specially delegated for this purpose in this investigation is concerned, it cannot accept such an investigation, as this would be a violation of the Constitution and the Criminal Procedure Act. But in individual cases the Austro-Hungarian authorities could be informed of the results of the investigation. "

On July 25, 1914, one day before the deadline, Baron Hold von Ferneck in the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry worked out a negative answer to Serbia's reaction in advance. If Serbia accepts all the conditions of the ultimatum, but also expresses the slightest protest, the reaction should be judged as inadequate for the following reasons: 1.) Because Serbia, contrary to its 1909 commitment towards Austria-Hungary, had adopted a hostile attitude, 2 .) Because it obviously called into question Austria-Hungary's power to hold Serbia accountable at its own discretion, 3.) because there could be no question of an internal reversal of Serbia, although it had been warned to do so several times, 4.) because Serbia clearly lacked the honesty and loyalty to meet the terms of the ultimatum. Even if Serbia accepts all the conditions without objection, it can still be noted that it has neither taken the steps required in the ultimatum nor informed about them.

The Austrian Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh spoke of the dismissal of the Serbian royal family, and that the wording of the passage in question allowed the interpretation that the Serbian government gave it. The Démarche did not perceive foreign countries any differently than the Serbian government. The shocked British Foreign Minister Sir Edward Gray, for example, spoke of the "worst document that he had ever come across". At the same time, Serbia began mobilizing.

With the declaration of war by Austria-Hungary on Serbia three days after the expiry of the ultimatum, the First World War began on July 28, 1914 .

Trial of the assassin

Čabrinović, Princip and the other assassins, with the exception of Mehmedbašić, were gradually arrested. During the interrogations they remained silent at first until they gave up at Princip's request and confessed everything, whereupon most of the other conspirators were arrested.

From October 12 to October 23, 1914, the trial against a total of 25 accused of high treason and assassination took place in Sarajevo . In the trial, all of the defendants denied any connection with official Serbia. Three of them were executed.

Nedeljko Čabrinović

Nedeljko Čabrinović gave the reason for his act that Franz Ferdinand was an enemy of the Slavs and especially the Serbs. He also stated that in Austria-Hungary the Germans and Hungarians had the say, while the Slavs were oppressed. Since he was a minor at the time of the offense, the court sentenced him to 20 years of heavy imprisonment in the Small Fortress Theresienstadt , exacerbated by a monthly fast and on June 28 of each year by hard camp and dark arrest. He died of tuberculosis on January 23, 1916 . Franz Werfel , who visited Čabrinović in Theresienstadt at the end of 1915, described the terminally ill person as the “chosen man of fate”.

Vaso Čubrilović

Vaso Čubrilović referred to himself as a “Serbo-Croat” in court and stated that his goal was to unite Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Bulgarians in one state. He was sentenced to 16 years of hard imprisonment, intensified as with Čabrinović. He was also a minor at the time of the crime and could therefore not be sentenced to death. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, he was released. He studied history and later worked as a teacher and university professor and became Minister of Forestry under Josip Broz Tito .

Veljko Čubrilović

Veljko Čubrilović, Vaso's brother, was found guilty of complicity in murder and was executed on February 2, 1915 in the " Philippovich Camp" barracks in Sarajevo, together with Miško Jovanović and Danilo Ilić, by hanging on the choke .

Trifun "Trifko" Grabež

Trifun “Trifko” Grabež called the act “the greatest revolutionary act in history”. He was sentenced by the court to 20 years of heavy imprisonment in the Small Fortress Theresienstadt , tightened as with Čabrinović. He too was too young to be sentenced to death. He died of tuberculosis in 1918.

Danilo Ilić

Danilo Ilić was found guilty by the court and sentenced to death; he was of legal age at the time of the crime. He was finally executed on February 2, 1915 in the barracks " Philippovich Camp" in Sarajevo together with Miško Jovanović and Veljko Čubrilović by hanging on the choke barrels.

Miško Jovanović

In order not to attract attention during a possible control on the way to Sarajevo, Princip Jovanović had previously handed over the weapons that were to be used in the attack in Tuzla and received them back in Sarajevo. Jovanović was found guilty of complicity in murder and was executed on February 2, 1915 in the barracks " Philippovich Camp" in Sarajevo together with Danilo Ilić and Veljko Čubrilović by hanging on the choke bar.

Ivo Kranjčević

Ivo Kranjčević, a Croat who hid Čubrilović's weapons after the assassination attempt, was sentenced to 10 years of hard imprisonment, as with Čabrinović.

Muhamed Mehmedbašić

Muhamed Mehmedbašić was the only person involved who was not arrested and fled to Montenegro , where he publicly boasted about his participation in the attack, so that the Montenegrins finally had to arrest him. Austria-Hungary demanded his extradition, which brought Montenegro into an uncomfortable dichotomy because it did not want to turn its own Serbian population against it. As if by chance, Mehmedbašić was able to break out of prison and go into hiding, whereupon he initially behaved inconspicuously. In 1917 he was arrested together with Dragutin Dimitrijević Apis, the leader of the Black Hand, for a plot of murder against the Serbian Prince Regent Aleksandar Karađorđević and sentenced to 15 years in prison. He was eventually given amnesty in 1919 and returned to Sarajevo, where he led a modest life as a gardener and carpenter. He died during World War II .

Cvetko Popović

Cvetko Popović was sentenced to 13 years imprisonment for high treason and was released after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. He was also a minor at the time of the crime. He later became a curator in the Ethnographic Department of the Sarajevo Museum .

Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip testified that he did not regret the act and did not consider himself a criminal either, that he had just murdered a tyrant . He said that he was a Serb and a revolutionary, hates Austria-Hungary and wished for its downfall. Nobody instigated him to act, he denied any official connection to Serbia. In support of this, he alleged that Ciganović had warned him that the Serbian authorities would arrest them if they found out about their plan. He also said that he was sorry to have killed the Archduke's wife, a Czech woman, and that the shot was intended for Potiorek.

Princip was found guilty of high treason and assassination by the court and sentenced to 20 years of heavy imprisonment, as with Čabrinović. His young age at the time of the crime was decisive for the verdict, which saved him from the death penalty. He finally died of bone tuberculosis in 1918 in the prison hospital of the Small Fortress in Theresienstadt .

Local reception

On June 28, 1917, on the occasion of the third anniversary of the murder, Austria-Hungary left a twelve-meter-high monument in honor of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie on the railing of the Latin Bridge, which bears this name because it is the shortest connection to the Roman Catholic cathedral erect, on which the passers-by were asked for a short prayer for the victims of the attack. The monument consisted of two columns, a large plate with the figures of the murdered couple and a niche for mourning candles and flowers. At the end of 1918 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had the monument dismantled and stowed in a museum depot; the altar of the monument was blown up in 1919. While the pillars were reused for other purposes, the plate with the figures of the couple heir to the throne is today (2006) in the art gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the stop are the remains of a concrete bench that was an integral part of the monument. Bosnia-Herzegovina is considering renovating the monument.

After the First World War, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia erected a granite memorial plaque in honor of Princip at the site of the attack, which was inaugurated on February 2, 1930. In the Serbo-Croatian language and Cyrillic characters was the inscription Na ovom istorijskom mestu Gavrilo Princip navijesti slobodu na Vidovdan 15/28 1914. godine (German. Gavrilo Princip brought freedom to this historical place on Vidovdan 15/28 1914). The panel was inaugurated on the occasion of the 15th anniversary of the death of the assassins Danilo Ilić, Miško Jovanović and Veljko Čubrilović and was until removal on 17 April 1941 a personal wish of Adolf Hitler as German nationals , the panel at the invading soldiers of the Wehrmacht handed over, on Location of the Sarajev assassination.

After the attack by the Wehrmacht on Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941 and the capture of Sarajevo on April 17, 1941, Hitler described the plate as the only war souvenir of relevance to him in occupied Yugoslavia and wished it on the occasion of his 52nd birthday on April 20, 1941 in the Command post of the Balkan War, the Führer headquarters "Spring Storm" in the so-called Führer special train America , in the presence of the Wehrmacht and Nazi party celebrities such as Wilhelm Keitel , Walther von Brauchitsch and Hermann Göring . The train, which was positioned in front of the 2,500-meter-long Great Hartberg Tunnel station near Mönichkirchen during the Balkan offensive , was 50 kilometers from the Yugoslav border. The presentation ceremony was captured by Hitler's personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann on April 20, 1941. Hoffmann's photograph was found by Muharem Bazdulj in the holdings of the Bavarian State Library in Munich for the weekly magazine Vreme . When it was published on October 31, 2013, it was considered a sensational find. Adolf Hitler is pictured in front of the Gavrilo Princip memorial plaque in the parlor of the train.

One day after May 6, 1945, on which Sarajevo was liberated by the Tito partisans, a new memorial plaque was put back on May 7 in place of the one that had been taken to the Berlin Zeughaus . On this was a golden inscription, in which a connotation to the partisan war was formed by the still ongoing war of liberation: U znak vječite zahvalnosti Gavrilu Principu i njegovim drugovima borcima protiv germanskih osvajača, 7. posvećuje ovu ploču omladina 1945 . godine (German: In the sign of eternal gratitude to Gavrilo Princip and his fighting friends against the Germanic conquerors, this plaque donates the youth of Bosnia and Herzegovina - Sarajevo May 7, 1945). On June 28, 1952, this was again replaced by a new plaque with a different message, this time again with an inscription in Cyrillic, which refers to the desire for freedom of the peoples of Yugoslavia: Sa ovoga mjesta June 28, 1914. godine Gavrilo Princip svojim pucnjem izrazi narodni protest protiv tiranije i vjekovnu težnju naših naroda za slobodom (German: From this place on June 28, 1914 Gavrilo Princip had with his shots expressed the people's protest against tyranny and the centuries-long striving of our peoples for freedom). This record was destroyed during the Bosnian War in 1992.

In Tito's Yugoslavia, Princip and the Mlada Bosna movement were revered as “young fighters for the freedom and independence of the Yugoslav peoples” and a small museum was opened in Sarajevo. Bosnian communists decided on May 7, 1945 in the first session of the USAOBiH (“United Alliance of the Antifascist Youth of Bosnia-Herzegovina”) to erect a new memorial plaque “as a token of eternal gratitude to Gavrilo Princip and his comrades, fighters against the Germanic conquerors” . The Latin Bridge was renamed Gavrilo Princip Bridge. At the place where Princip is said to have stood during the assassination, a stone slab with footprints was erected, which was destroyed during the Bosnian War in the 1990s. In 1977 a memorial plaque was erected to depict Princip as a national hero.

After the Bosnian War in the 1990s, the Princip Bridge was renamed Latin Bridge again. At the site of the attack there is now a plaque with a neutral inscription in Bosnian and English.

Museum reception

Konopiště Castle, Artstetten Castle, Capuchin Crypt

The death masks of the Archduke and Countess, made of plaster after the attack, are exhibited in the Czech Konopiště Castle . Identical examples made of marble can be viewed in Artstetten Castle . The medals and decorations worn by Franz Ferdinand on the day of his murder are also there, and the blood-stained dress of the Duchess of Hohenberg has been preserved. In Artstetten Castle, the two victims of the attack rest in the crypt below the castle church. The castle itself also houses an “Archduke Franz-Ferdinand Museum”, which shows him not only as an official and dignitary, but also as a private person. The blood-soaked shirt of the Archduke, which his descendants entrusted to the order of the Jesuits for preservation, is kept in the Army History Museum in Vienna. In 1984 a plaque made of white marble was placed in the Capuchin Crypt . This reminds us that Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess von Hohenberg are buried in the crypt of Artstetten Castle. Both (historically incorrect) as the first victims of the First World War are engraved on the war memorial in the municipality of Artstetten as well as on the memorial plaque in the Capuchin Crypt.

Army History Museum Vienna

The exhibition is located in the so-called “Sarajevo Hall” of the Army History Museum (HGM) in Vienna. The automobile in which Franz Ferdinand and his wife were shot is shown. This is a six-seater passenger car from the Gräf & Stift brand , type: double Phaeton body , four cylinders, 115 mm bore, 140 mm stroke, 28/32 hp, engine no.287, Vienna registration number: A III-118. From the first stop, splinter impacts can be seen on the left and on the rear side of the car. On the right wall of the carriage through the shot pistols projectile visible Duchess of Hohenberg was killed by at the second stop.

The vehicle belonged to Count Harrach , a friend of the imperial family. The car was delivered by the manufacturer to Harrach on December 15, 1910 and, as a member of the Voluntary Automobile Corps, made it available to the heir to the throne for the maneuvers in June 1914. After the attack, the automobile was initially kept in the Konak of Sarajevo . Owner Count Harrach dedicated it to Emperor Franz Joseph, who in July 1914 ordered the vehicle to be transferred to the then Austro-Hungarian Army Museum. There the car was exhibited for inspection in the general hall of the museum from 1914 to 1944. During the bombing of the Vienna Arsenal , the car suffered damage to the upholstery and the wheels, which could, however, be restored. The car has been at its current location in the Army History Museum since June 1957. Harrach's descendants claimed the car back in 2003 without success, so it is still in state ownership.

The Archduke's uniform is also on display, consisting of a gauntlet with a green plume for German generals, a pike-gray tunic for generals of III. Rank class, blue-gray pantaloons (trousers) with scarlet lampasses , a field band for generals and white deerskin gloves. The tunic has a small bullet hole at the seam to the collar base, below the three general stars on the right-hand side, through which the steel-jacketed bullet from the assassin's pistol penetrated, tore the heir to the throne's neck vein and injured the trachea. The skirt is soaked in blood on the inside and front, there are also traces of blood on the trousers. Incisions on the left chest part of the skirt and on the left sleeve are from the first attempts to rescue the dying person. The back of the skirt is cut open from the collar to the left part of the lap, a measure that was intended to make it easier for the archduke to put on the already rigid corpse for laying out. In the inside of the skirt the middle part of the right back lining is almost completely removed. This is due to the fact that strangers, probably when cutting open the back, cut small pieces out of the white silk lining as souvenirs . Such pieces of fabric later came into circulation and were still to be found in Yugoslavia after the Second World War . This even led to rumors that the uniform of the heir to the throne had been dismembered after the assassination and that the tunic on display at the HGM was therefore wrong.

Pictures from the Army History Museum in Vienna

The uniform of the heir to the throne, consisting of a hat, field bandage, tunic and trousers as well as a pair of train ankle boots with spurs, which are not exhibited, was given to the Imperial and Royal Army Museum on July 22, 1914 at the request of the children of the heir to the throne. The Archduke's gloves were not given to the museum by private parties until 1915.

The weapon used by Princip, a 9 mm FN Browning pistol model 1910 from the Belgian company Fabrique Nationale with the serial number 19074, can also be seen there, as well as a large number of photos clearly documenting the assassination. The 9 mm FN Browning model 1910 pistol with the serial number 19074 was in the possession of the Viennese Jesuits who received it from the Viennese court after the assassination attempt. It is assumed that this pistol was most likely the murder weapon. In the possession of the Jesuits, who were commissioned by the descendants to preserve this memory, there was also a blood-soaked rose that was worn on the belt by the Duchess of Hohenberg on the day of her murder. These objects were given to the Army History Museum on special loan in 2004.

Every year, around the anniversary of the assassination, the blood-soaked shirt of the heir to the throne is shown in the Army History Museum. For conservation reasons, the exhibit can only be exhibited to a limited extent. The exhibit is on loan from the Austrian Province of the Society of Jesus , which the descendants received for safekeeping. The undershirt that Franz Ferdinand was wearing on the day of the attack was originally intended for a memorial room in a youth home run by the Jesuits in Sarajevo. The Jesuit Father Anton Puntigam , who donated the last unction to the Archduke in the town hall of Sarajevo and consecrated the body, was no longer able to realize his planned project of a Franz Ferdinand Museum. Due to the course of the war and the events in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the shirt was finally brought to Vienna to the headquarters of the Austrian province of the Society of Jesus, where it was kept in the archive for 90 years. At the request of the order and with the consent of the family members and in particular of Artstetten Castle, the HGM took over this unique and historically valuable shirt to make it accessible to visitors.

Sarajevo Museum 1878–1918

The museum shows aspects of the history of Sarajevo during the time of the Austro-Hungarian occupation since the Berlin Congress . The focus is on the attack. a. the weapons used and maps with the position of the assassins are shown. The branch of the Museum of Sarajevo is located in the building in front of which Princip shot the heir to the throne and his wife.

Movies

- Sarajevo - About Throne and Love , Austrian film from 1955

- The Man Who Defended Gavrilo Princip , a 2014 Serbian feature film

- The assassination attempt - Sarajevo 1914 , a German-Austrian cooperation from 2014

Historical novels

- Ulf Schiewe : The assassin. Historical thriller . Bastei Lübbe TB, Cologne 2019, ISBN 978-3-404-17903-9 .

literature

- Wladimir Aichelburg : Sarajevo. The assassination. June 28, 1914. The assassination attempt on Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Este in photo documents. Verlag Österreich, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-7046-1386-X .

- Volker R. Berghahn : Sarajevo, June 28, 1914. The fall of old Europe. (= 20 days in the 20th century. - dtv 30601) Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-30601-7 .

- Gordon Brook-Shepherd : The Victims of Sarajevo. Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Sophie von Chotek. Engelhorn, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-87203-037-X .

- Milo Dor : The shots in Sarajevo. Roman (= dtv 11079). Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-423-11079-1 (Also called: The Last Sunday. Report on the assassination attempt in Sarajevo. Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna et al. 1982, ISBN 3-85002-161-0 ).

- Hans Fronius : The assassination attempt in Sarajevo. With a foreword by Dieter Ronte and an essay by Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck . Styria, Graz et al. 1988, ISBN 3-222-11851-5 .

- Michael Gehler , René Ortner (Eds.): From Sarajewo to September 11th. Individual assassinations and mass terrorism , Innsbruck 2007.

- Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ed.): A onda, odjeknuo per onaj HITAC u Sarajevo ... / And then, in Sarajvo the shot fired ... what . Self-published, Sarajevo 2015, ISBN 978-9958-9569-2-8 .

- Hermann Kantorowicz : Expert opinion on the war guilt issue 1914. European publishing company, Frankfurt am Main 1967.

- Christian Ortner , Thomas Ilming: The Sarajevo Car. The most historic oldtimer in the world , Verlag Edition Winkler-Hermaden, Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-9503611-4-8 .

- Erich Pello: Sarajevo, crime scene Latin bridge. The author spoke to people and took photos on site. Verlag Edition Winkler-Hermaden, Vienna, 2014, ISBN 978-3-9503611-5-5 .

- Vahidin Preljević, Muamar Spahić: Sarajevo assassination . From Bosnian to English by Coral Petkovich. Vrijeme, Zenica 2015. ISBN 978-9958-18-072-9 .

- Friedrich Würthle: The trail leads to Belgrade. The background to the Sarajevo drama in 1914. Molden, Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1975, ISBN 3-217-00539-2 .

Web links

- Historical e-paper facsimile and transcribed historical edition of the Frankfurter Zeitung from June 30, 1914 on the course of the assassination attempt in Sarajevo.

- Film of Franz Ferdinand's arrival at Sarajevo City Hall on June 28, 1914 and of his funeral

- The attack in the mirror of the Austro-Hungarian press (Austrian National Library)

- The Austro-Hungarian documents on the outbreak of war

- DeutschlandRadio Berlin, broadcast on June 28, 2004

- A hand grenade against the heir to the throne - State Exhibition 2009

- Erich Follath: Sarajevo assassination 100 years ago . In: Spiegel Online . September 24, 2013.

- Gregor Mayer: Princip, Gavrilo , among others , in: Kurt Groenewold , Alexander Ignor, Arnd Koch (Ed.): Lexicon of Political Criminal Processes , online, as of January 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Manfried Rauchsteiner : The First World War and the end of the Habsburg Monarchy 1914–1918. Böhlau, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-205-78283-4 , p. 87.

- ^ Austro-Hungarian Red Book. Diplomatic files on the prehistory of the war in 1914. Popular edition. Manzsche kuk Hof-Verlags- und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Vienna 1915, Doc. 1, p. 8.

- ^ Leon Biliński : Bosna i Hercegovina u uspomenama Leona Bilińskog. Institut za istoriju, Sarajevo 2004, ISBN 9958-9642-4-4 , p. 101.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle: Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne ²1994, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 , p. 63 f.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 , p. 64.

- ↑ a b Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 89.

- ↑ Würthle: The trail leads to Belgrade. The background to the Sarajevo drama in 1914. Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1975, pp. 32 ff., 276 (end note 29).

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , pp. 95, 477.

- ↑ Jörn Leonhard : Pandora's box. The history of the First World War. Chapter 3: Derailment and escalation: Summer and autumn 1914. Munich 2014, Kindle edition item 1572.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 79 ff.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg Monarchy 1914–1918. Böhlau, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-205-78283-4 , p. 106.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson : The False War. The First World War and the 20th Century. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-421-05175-5 , p. 191.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: Russia's Road to War. The First World War - the origin of the catastrophe of the century . Europa Verlag, Berlin / Munich / Vienna 2014, p. 84 ff.

- ↑ a b Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 85.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 79.

- ↑ a b Manfried Rauchsteiner: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg Monarchy 1914–1918. Böhlau, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-205-78283-4 , p. 89.

- ↑ Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2013, p. 80.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 88.

- ↑ Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ed.): A onda, odjeknuo per onaj HITAC u Sarajevo ... / And then, in Sarajvo the shot fired ... what . Self-published, Sarajevo 2015, p. 42 f.

- ↑ Preljević, Spahić: Sarajevo assassination . Zenica 2015, p. 108 f.

- ↑ Würthle: The trail leads to Belgrade. The background to the Sarajevo drama in 1914 . Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1975, p. 12.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Translated from the English by Norbert Juraschitz. DVA, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 480 (there, however, without attributable source information).

- ^ Interrogation protocol p. 50, quoted in Würthle: The trail leads to Belgrade. The background to the Sarajevo drama in 1914 . Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1975, p. 12.

- ↑ Würthle: The trail leads to Belgrade. The background to the Sarajevo drama in 1914. Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1975, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Translated from the English by Norbert Juraschitz. DVA, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 481 f.

- ↑ Prager Tagblatt. No. 176, June 29, 1914, p. 2/2 ( weblink ÖN ).

- ↑ John S. Craig: Peculiar Liaisons. In War, Espionage, and Terrorism in the Twentieth Century. Algora Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-87586-333-7 , p. 24.

- ↑ Würthle: The trail leads to Belgrade. The background to the Sarajevo drama in 1914. Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1975, p. 14 ff.

- ^ Theodor von Sosnosky : Franz Ferdinand the Archduke heir to the throne. A picture of life. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1929, p. 208.

- ^ A b c d Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck : The Army History Museum Vienna. Hall VI - The k. (U.) K. Army from 1867 to 1914. Vienna 1989, p. 53.

- ↑ Armin Pfahl-Traughber : The anti-Semitic-anti-Masonic conspiracy myth in the Weimar Republic and in the Nazi state , Braumüller, Vienna 1993, p. 34.

- ↑ Wiesner's telegram of July 13, 1914 at World War I Document Archive .

- ↑ Friedrich Wiesner: The murder of Sarajevo and the ultimatum. In: Reichspost of June 28, 1924, p. 2 f.

- ↑ a b c d Sebastian Haffner : The seven deadly sins of the German Empire in the First World War . Verlag Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1981, ISBN 3-7857-0294-9 , p. 26.

- ^ Austro-Hungarian Red Book. Diplomatic files on the prehistory of the war in 1914. Popular edition. Manzsche kuk Hof-Verlags- und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Vienna 1915, Doc. 19, pp. 32–48.

- ^ Telegram from the Imperial Chancellor from Bethmann Hollweg to the German Ambassador in Vienna Tschirschky on July 6, 1914.

- ^ Correspondence from German embassies June-July 1914 with comments from Kaiser Wilhelm II.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Graz et al. 1993, p. 75.

- ^ Letter from Count Berchtold to Count Tisza of July 8, 1914 .

- ^ Minutes of the meeting of the Council of Ministers for Common Affairs on July 19, 1914 .

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Graz et al. 1993, p. 79.

- ^ Austro-Hungarian Red Book. Diplomatic files on the prehistory of the war in 1914. Popular edition. Manzsche kuk Hof-Verlags- und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Vienna 1915, Doc. 7, pp. 15–18 .

- ↑ Count Berchtold's telegram to Baron von Giesl in Belgrade on July 23, 1914 .

- ↑ Notifying memorandum of the Russian Council of Ministers to Serbia from 11./24. July 1914 .

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria Verlag, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 , p. 79.

- ^ Austro-Hungarian Red Book. Diplomatic files on the prehistory of the war in 1914. Popular edition. Manzsche kuk Hof-Verlags- und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Vienna 1915, Doc. 37, p. 117.

- ↑ Friedrich Heer : Youth on the move. Gütersloh 1973, p. 101.

- ↑ Vladimir Dedijer : Sarajevo 1914. Prosveta, Beograd 1966, p. 456.

- ↑ Ernst Trost : That stayed with the double-headed eagle. On the trail of the sunken Danube monarchy. Fritz Molden Verlag , Vienna 1966, p. 332.

- ↑ Indira Kučuk-Sorguč: Prilog historiji svakodnevnice: Spomenik umorstvu - okamenjena prošlost na izdržavanju stoljetnje kazne . In: Prilozi (Contributions) . No. 34 , 2005, pp. 63-65 ( ceeol.com ).

- ↑ a b c Muharem Bazdulj: Srećan rođendan, gospodine Hitler Srećan rođendan, gospodine Hitler (German: Happy birthday Herr Hitler) . In: Vreme , No. 1191, October 31, 2013.

- ↑ BArch MSg 2/5876 The commander Führerhauptquartier ( Memento of 10 November 2013, Internet Archive ).

- ↑ When a piece of (war) history was being written in southern Lower Austria in April 1941 .

- ↑ Bild hoff-35114 and Bild hoff-35336 , Photo archive Hoffmann P.83, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- ↑ Andrej Ivanji: The leader's epochal vengeance - A picture as a bracket for two world wars . In: Der Standard , November 29, 2013.

- ↑ ORF online: 1914–2014: Photography causes a stir , November 1, 2013.

- ^ Robert J. Donia: Sarajevo: a biography. University of Michigan Press, 2006, ISBN 0-472-11557-X , p. 206.

- ^ Archives Schloss Artstetten / Museum / Count Romee de La Poeze d'Harambure / 1984.

- ↑ a b c Archive of Artstetten Castle / Sarajevo / Estate.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner, Manfred Litscher (ed.): The Army History Museum in Vienna. Graz, Vienna 2000, p. 63.

- ↑ Information from Father Thomas Neulinger SJ , in: Das Assentat von Sarajevo ( ORF documentary), online interview at 0:01:25 min.

- ^ Archive Artstetten Castle / Sarajevo / Estate / Correspondence.

- ↑ The heir to the throne's bloody shirt exhibited again until July 11, 2010. (No longer available online.) Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; Retrieved June 28, 2010 .

- ^ Sarajevo Museum 1878-1918

- ^ The Man Who Defended Gavrilo Princip (2014) I. IMDb.com, accessed on January 21, 2017 (English).

Coordinates: 43 ° 51 ' N , 18 ° 26' E