Wenamun's travelogue

| Wenamun in hieroglyphics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surname |

Wenamun (Wen Amun) Wn Jmn |

||||||

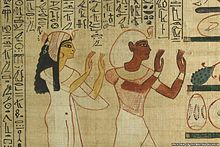

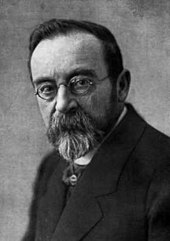

The travelogue of Wenamun (also report Wenamun , narrative of Wenamun , Papyrus Moscow 120 ) is an untitled original work of ancient Egyptian literature . The text is written in hieratic script as well as in the New Egyptian language and has only survived in Papyrus Moscow 120, which Vladimir Semjonowitsch Golenishchev acquired in an antique trade in 1891 and which was apparently found near the place el-Hibe . The action takes place in the transition period from the New Reich to the Third Intermediate Period(approx. 1075 BC) and reflects the political situation at that time very well, which is why it was sometimes used as a historical source. The actual time of writing should be to set about 150 years later, probably in front of the Palestinian campaign of Sheshonq I .

The story tells of the temple official Wenamun, who is sent by Herihor , a high priest of Amun in Thebes , to get lumber for Amun's boat in Byblos . Wenamun makes enemies of the Tjeker (a sea people ) and ends up penniless in Byblos, where he is not welcome. Only an oracle by an ecstatic at the court of Prince Tjeker-Baal there gives the instruction to receive Wenamun. So he can still get the wood he wants. On the way home, however, he meets the Tjekers again, gets caught in a storm while fleeing and ends up in Alašija ( Cyprus ), whereupon the story breaks off.

The story shows the dwindling political power of Egypt abroad, but tries to demonstrate the power of the god Amun beyond the national borders. According to the most recent presentation by Bernd U. Schipper , it is an artistic work that was deliberately placed in the field of tension between historical report, literary story and religious and political intention .

Finding circumstances

The papyrus with the story of Wenamun was acquired by Vladimir Semjonowitsch Golenishchev (1856 to 1947) in an antique trade in Cairo in 1891 . According to him, the Fellachians had recently found it together with other papyrus rolls in an earthen vessel near the town of el-Hibe (Teuzoi). The entire Golenishchev collection later became the property of the Pushkin Museum . The said papyrus bears the inventory number 120 (pMoskau 120). The other two texts that were found with him are Papyrus Moscow 127, the so-called Letter of Wermai , and Papyrus Moscow 169 with the so-called " Onomasticon des Amenope ".

The el-Hibe site is about 35 km as the crow flies south of Beni Suef . Other remains from the 21st Dynasty to the Coptic period have also been found there. A fortress was built for the rule of Upper Egypt in the 21st dynasty, which was equipped with a temple for the god Amun under Scheschonq I and Osorkon I , in which a local form of Amun ("Amun-great-an-roar" ) and the Theban Triad were worshiped. The city is inscribed in the so-called el-Hibe correspondence, the chronicle of Prince Osorkon and the demotic papyrus Rylands IX.

Mikhail Alexandrowitsch Korostowzew already suspected that the story of Wenamun was kept in the archives of the temple of el-Hibe:

“It is natural that the account or story of Wenamun, the messenger of the High Priest of Amun of Thebes at Byblos, should be stored somewhere in the archives of the Priesthood of Amun. Not only the object [of the plot] of the papyrus, but also the representation in its ideology show a related connection of this text to the priesthood of Amun. "

Geoffrey A. Wainwright interpreted the fact that the Wenamun papyrus was found in Teuzoi (el-Hibe) - and not in Thebes - even to the extent that “either the archives were in Teuzoi, or if he had the record of his Deeds had retained that a high official like Herihor's official representative had lived there and was buried. "

Of course, it cannot be concluded that the text originally belonged to el-Hibe and all connections between the text and this city remain speculation, also due to the fact that the narrative is only recorded on a papyrus. Still, it fits this place amazingly well. It is the secondary residence of the Theban high priests and station on the way to the Near East.

papyrus

Since the papyrus consists of individual fragments, it was initially unclear how many pages it was made up of. Vladimir Golenishchev assumed that the text would consist of three pages, of which one had the first quarter and the second half of the first sheet. Then there is the entire second leaf and the (very disheveled) beginning of the third leaf. It was only Adolf Erman who realized that the piece from what was supposed to be the third leaf actually belongs in the large gap on the first page. Erman's orders were largely followed by Gardiner and Korostowzew in their editions of the papyrus, as was the Egyptologist Lurje and the papyrus restorers Ibscher and Alexandrovsky. This results in the following arrangement: I, 1-27, then Gol.III, 1–14, then I, x + 1 to I, x + 24 and II, 1-83. Since apparently no line is missing from the first page, Alan Gardiner suggested that the lines should be numbered consecutively, that is: I, 1-59 and II, 1-83.

Vladimir Golenishchev also mentioned a small fragment of papyrus which he had received from his friend Heinrich Brugsch and which can also be assigned to this story. He later said that it referred to the second sheet. After that, however, it is no longer mentioned. Where it is is unexplored.

From the description of Korostowzew and Alexandrovsky it emerges that the pages consist of individual pieces of papyrus, approx. 18 cm in size, bonded with glue. The fibers of the papyrus run perpendicular to the direction of writing. On the back of the second page, between lines 1.56 and 1.48, there are also two lines of text perpendicular to these, which apparently have nothing in common with the story of Wenamun.

Dating

The plot of the story takes place in the transition period from the New Kingdom to the Third Intermediate Period (end of the 20th dynasty, beginning of the 21st dynasty). Ancient times refer to the year of a ruler's reign, and the text itself indicates the beginning of the action as the 16th Schemu IV (April) in the fifth year, but the ruler is not named. From the beginning it was disputed which ruler this date refers to. The text mentions Smendes I and Herihor , who shared power over Egypt at the beginning of the 21st dynasty, with their seat in Tanis and Thebes. The last king of the 20th dynasty, Ramses XI. , is not mentioned. Adolf Erman and James H. Breasted said that the year was still based on Ramses XI. refer to the fact that Smendes I and Herihor already held power in Egypt during his lifetime.

Ramses XI. tried in vain to counteract the fall of the New Kingdom. In his 19th year of reign he ushered in a period of renaissance, the so-called Wehem-mesut era (“renewal of births”). This should be a conscious new beginning and a flowering period should begin after a period of decay. It is documented that at the beginning of the "Wehem-mesut era" was re-dated. Accordingly, Hermann Kees argued that the date of the Wenamun narration referred to this era. Accordingly, Wenamun would be in the 23rd year of Ramses XI's reign. set out on his journey. Many Egyptologists followed this view.

Jürgen von Beckerath raised a number of objections to this view:

- In the text Tanis is mentioned as the metropolis in the north, not Pi-Ramesse , the residence of Ramses XI.

- Wenamun and the Byblos prince make derogatory comments about a Chaemwese. However, this name is only available under Ramses IX. and Ramses X. proves what is against a dating to the time of Ramses XI. speaks.

- The designation of Chaemwese as "man" (rmṯ) is explained against the background of the new kingship of the 21st dynasty.

- The talk of the "other great Egyptians" refers to the division of Egypt into individual principalities and thus to the 21st dynasty.

The year five thus relates to the time after Ramses XI. The question remains whether the date is after the reigning Pharaoh Smendes or after the Theban high priest Herihor. Depending on the assessment of their role, research tends either in one direction or the other. Regardless of this, according to the current approaches of Egyptian chronology, one can assume that Wenamun was around in 1065 BC. Started on his journey.

The script itself is dated to the 21st or (early) 22nd dynasty on the basis of paleographic studies, i.e. approx. 100–150 years after the time of the action. For reasons of content, the reign of Scheschonq I is assumed to be the time of writing . Under him, Egypt again had central power for the first time, and through its successful Palestine campaign it again played a role in foreign policy, which was legitimized by the idea of Amun-Re as king and god over Syria / Palestine.

In a literary critical analysis, Schipper could not work out an older model - the text is literarily uniform and contains no breaks or duplications. His historical analysis has shown, however, that the events may well have had a real core, which leaves the question of whether there was an orally told template.

content

Herihor is the high priest of the god Amun in the city of Thebes . He sends Wenamun to fetch timber for the Amun's boat . Wenamun first went to Tanis to see the regent Smendes I and his wife Tanotamun. After a waiting period of several months, he will be equipped with a ship and crew on New Year's Day 1st Achet I (month of February) of the following year so that he can sail into the great Syrian Sea.

First Wenamun arrives at Der , a port city of the Tjeker , a sea people . There he is received by a city prince named Bedjer, while a crew member steals Wenamun's gold and silver and flees. Wenamun asks Prince Bedjer for damages. However, the prince points out that the thief belongs to Wenamun's own crew. But he offers Wenamun his hospitality for a few days so that the thief can be found. After nine days of waiting, Wenamun complains again to the prince about the unsuccessful search and continues to travel. The following lines are difficult to understand due to the severe destruction of the papyrus. As Wenamun approaches the city of Byblos , he apparently steals silver from a ship of the Tjeker; he wants to keep it until his own money is found. In doing so, Wenamun turns the Tjeker into enemies. It is also unclear what happened to Wenamun's ship, as it is no longer mentioned in the episode.

In the port of Byblos, Wenamun pitched his tent on the seashore on Peret I (June). He hides the looted money and an Amun statuette that he is carrying in a safe place. Here he waited 29 days for a ship going to Egypt. Tjeker-Baal, the prince of Byblos, is not happy about his presence and sends a message to him every day: “Get out of my harbor!” Wenamun obviously failed in his mission.

Wenamun finally finds a ship to Egypt. But then it happens at a sacrificial ceremony of Prince Tjeker-Baal that the god Amun takes power over an ecstatic. Amun lets him tell the prince that he must not let Wenamun leave, but rather bring the Amun statuette, because it is Amun himself who sent Wenamun. Wenamun was given the opportunity to present his concerns to the prince on 1st Peret II (July). Wenamun also explains that it has now been a full five months since he left Tanis.

Tough negotiations ensue. Tjeker-Baal does not take Wenamun seriously at first and does not recognize the Egyptian rulers as his. Wenamun, however, refers to Amun's omnipotence. His commission goes back to a divine oracle of Amun. The required purchase price for the wood is ultimately purely material, what Amun has to offer is far more valuable: the ideal values of life and health.

In the end, Tjeker-Baal does - albeit not without material equivalent - still go into the trade. Wenamun sends a messenger to Smendes and Tanotamun, who then bring the necessary currency from Egypt. Tjeker-Baal has the timbers prepared and brought to the port. At this point in time, almost two years have passed since Wenamun's departure: “Can't you see the migratory birds that have already migrated to Egypt twice? Look at them as they move to Qebehu ”. When Wenamun goes back to the sea to finally return to Egypt, he sees eleven Tjeker ships that have been ordered to arrest him.

Prince Tjeker-Baal calls a council meeting with the Tjekers and explains to them that he cannot have Wenamun arrested in the middle of his country. He had Wenamun sent out, only then could they arrest him on the open sea. Wenamun escapes arrest and the wind blows him to Alašija (Cyprus). The inhabitants of the country want to kill him, but he manages to get through to Hatiba, the princess of the city. With good arguments, he gets her to spare his life. The princess then reprimands the people who threatened Wenamun. The text ends quite abruptly at this point with the words "lie down" / "goodbye".

Historical background

The story of Wenamun takes place in the transition period from the New Kingdom to the Third Intermediate Period and reflects the political situation of this time very precisely, which is why it has often been used as a historical source.

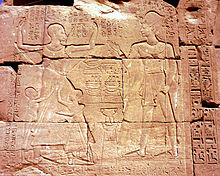

Under the reign of Ramses XI. the unrest in Thebes, which developed in the previous decades, intensified: problems with predatory Libyan tribes, famine, grave robbery, theft in temples and palaces and even civil war-like conditions. With the help of the Viceroy of Nubia , Panehsi and Nubian mercenaries, Ramses XI. The riots in Thebes ended, but there were disputes over competence between Panehsi and the high priest of Amun , Amenophis , which resulted in a war that spread to Pi-Ramesse . Ramses XI. sent General Pianch to Thebes and Panehsi could be driven back to Nubia. The king tried to initiate a new beginning, a Renaissance era ( Wehem-mesut era ), which was also made clear in the counting of the year: “The king founded a 'repetition of creation', in which the year 19 of Ramses XI. The year 1 of the Renaissance became, but every effort in this marauded state was in vain. ”The reliefs of this time in the Karnak temple are impressive evidence of the shrinking power of the Egyptian king and the increasing claim to power of the high priests of Amun in Thebes. In these the high priest Amenhotep is the same size as the king Ramses XI. presented what would have been unthinkable in earlier times.

In Thebes Pianch became high priest of Amun and after his death his son-in-law Herihor , who after the death of Ramses XI. even assumed royal titles. In the north of the country Smendes I ascended the throne and with these two men the 21st dynasty begins. This situation is also found in the story of Wenamun, in which Thebes is ruled by Herihor and Tanis by Smendes. The Thebais (and in theory actually all of Egypt) was considered to be the property of Amun. Eduard Meyer speaks of a divine state of Amon of Thebes . On a stele of Herihor at the entrance door to the interior of the Chons temple in Karnak the official course of this transition is indicated, in which it is stated that the intervention of the god Amun replaced the royal regiment with that of the high priest.

The story also shows the conditions in maritime trade at that time, when individual seafaring groups, so-called sea peoples , controlled the trade. There was a regionalization and "democratization" of sea trade, that is, trade was no longer a royal privilege, but was open to every seafaring group. It was split into several smaller trading rooms. The island of Cyprus in particular gained importance in maritime trade. Michal Artzy describes the sea peoples as "nomads of the sea", a group of traders who played an important role in the late Bronze Age long-distance trade. With the collapse of the economic system at the end of the Late Bronze Age, the sea peoples probably went over to piracy more and more, which gave rise to the image of them that the Egyptian and ancient oriental sources reflect. Research does not agree on the origin of the sea peoples; the Mycenaean - Aegean area or the Mycenaean influenced Anatolia would be possible .

In relation to Egypt, the city of Byblos was of great importance as a trading center. There had been close trade contacts between Egypt and Byblos since the Old Kingdom , and Byblos in particular was an important timber supplier. This trade relationship eventually turned into a political dependency. The city kings of Byblos were vassals of the Egyptian pharaohs, even wrote their names in Egyptian hieroglyphics and carried Egyptian titles. Thutmose III. had a temple of Hathor built in Byblos. The Amarna correspondence also makes the close ties to Egypt visible. Due to the imprecise stratigraphy, it is difficult to determine from the archaeological finds and findings from Byblos what significance the city had at the transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age I and how strong the contacts with Egypt were. Finds of Egyptian king statues of Scheschonq I , Osorkon I and Osorkon II suggest, however, that the political importance of the city as a supraregional trading metropolis continued.

During the entire 21st dynasty there was a confrontation between the Theban high priests and the Tanite pharaohs. Only Scheschonq I, the founder of the 22nd dynasty, was able to reunite Egypt domestically by being able to bring the priesthood of Thebes under control with a clever personnel policy. Like the Tanite kings of the 21st dynasty, Scheschonq I was descended from an ethnic group that invaded Egypt from Libya towards the end of the New Kingdom. For the first time under him, Egypt played a role in foreign policy again. In the last years of the government he undertook a successful campaign to Syria / Palestine. It was probably about the control of the trade routes, but also about realpolitical implementation of Egypt's traditional claims in this area. In the religious field, this claim is connected with the god Amun-Re, which fits well with the intention of the Wenamun story.

Benjamin Sass thinks it is possible that the descriptions of the Levantine coast in the Wenamun story are anachronistic , that is, that they do not reflect the conditions at the time of the action but at the time of writing, i.e. about 150 years later. For example, the city of Dor could have been under the influence of the Tjekers at the time of Scheschonq I, which is confirmed by recent C14 data.

Language and style

In terms of content, form and style, the story of Wenamun appears simple and lackluster , for example in comparison to the story of Sinuhe . It is stylistically different from most other Egyptian stories and on the surface it appears realistic in the representation of events, which is why it was often viewed as a copy of an official statement of accounts instead of a work that was fictitious. The language is pure New Egyptian .

The format, arrangement of titles, names of officials, dates and the built-in lists of goods are reminiscent of files from Egyptian chancelleries. In terms of content, the story also has a lot in common with reports of foreign experiences by officials who recorded them in honor of their rulers and on memorial stones in the expedition area.

“But the witty dialogues, which take up far more space than the description of the facts, and lovingly painted individual features [...] do not belong in a sober factual report. [...] Especially in the variedly designed alternate speeches, the story of Wen-Amun is close to a group of NR stories that, like them, are written in New Egyptian, that is, in contemporary colloquial language, and various topics from mythology and history are frank and sometimes treated with humor in order to entertain an educated audience. "

The events are usually described in the first person, from Wenamun's point of view, but this perspective is not strictly adhered to. In some events, the protagonist was not present and it is unclear how he learned about them.

In terms of text type, the story of Wenamun with a number of other New Egyptian stories such as the two-brother fairy tale , the fight between Horus and Seth or the prince's story can be assigned to the prose texts , which are characterized by “phenomena such as sentence introductions such as .n. sḏm.n = f, wn.jn sḏm.n = f (ie then he heard ...) or the like, due to strong differences in the number of syntactic elements and thus the sentence lengths, due to the use of finite verbal forms, u. Ä. ”. A prose text is mainly defined by the lack of verse-constructing elements and the artistic form is also revealed in Wenamun's analysis of the entire text.

Helmut Satzinger made the discovery that many unsolved grammatical problems arise from passages spoken by non-Egyptians. After an analysis, he came to the conclusion that the Wenamun narrative may contain the unique case that the foreigners were imitated by their typical foreign language:

“He [the author] let them [the foreigners] make exactly those linguistic careless mistakes that a listener or reader would expect them to do, such as wrong pronouns and wrong verb forms. Of course, it did not tire the listener / reader by not continuing with it all the time - just here and there, as a masterful trick to catch the reader's attention and reaction. "

However, this thesis met with a rather negative attitude among Egyptologists.

Individual questions

The ecstatic of Byblos

The figure of the ecstatic at the court of the Byblos prince gave rise to many interpretive approaches. This evidence of ecstatic seerism has no parallel in Egyptian literature. He is referred to as ˁḏd ˁ3 , which literally means “big boy”. Many translations and edits stay close to this literal translation.

Since this episode leads into the realm of Syrian prophecy, more recent studies also try to explain the term for the ecstatic with terms from this area. These refer mainly to the Aramaic CCNR inscription from Hamath , in which a seer is mentioned who bears the title ˁdd there ; Something similar can be found in the Mari letters.

Although ˁḏd is not the correct Egyptian transcription of the Semitic ˁdd , since Egyptian ḏ does not correspond to d but to z / s, it is possible that the term was Egyptized based on the word “boy”. The addition of ˁ3 (“large”) may serve to rule out the misunderstanding that it is a child.

However, the use of the determinative “child seated with hand to mouth” indicates that they were young people.

The largest collection of prophetic documents comes from the city-state of Mari from the Old Babylonian period, that is, from the 18th century BC. It contains 50 letters in which prophetic words are quoted. The Mari letters also report prophetic appearances in Aleppo and Babylon . The second largest corpus of this prophecy comes from the Assyrian state archives in the ruins of Nineveh , the Assyrian capital. This Neo-Assyrian prophecy corpus from the 7th century BC BC consists of eleven clay tablets with a total of 29 individual oracles of the prophets to the kings Asarhaddon (681–669 BC) and Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC). Most of these oracles were created in a situation that a rule was endangered and required special legitimation or the support of a god.

Pharaoh's shadow

The passage II, 45-II, 47 with the “Shadow of the Pharaoh” aroused particular interest in research: After the wood has been prepared for Wenamun, he and Tjeker-Baal meet again. Wenamun comes so close to him that the shadow of the lotus leaf of Tjeker-Baal falls on Wenamun. A servant of the prince intervenes with the words: "The shadow of Pharaoh - he live, be safe and sound - your master, has fallen on you." The prince becomes angry about this and says: "Leave him!"

Adolf Erman interpreted the passage as a joke on the part of the servant. Building on this, H. Bauer saw it as a play on words with the Phoenician word for "twig, palm twig, frond" and therefore suggested: "the shadow of his frond" fell on him. Adolf Leo Oppenheim saw Mesopotamian - Assyrian ideas in the passage , such as the "merciful shadow of the king" and that those who stay in the king's shadow enjoy special privileges. Eyre thought the passage was ironic . In principle, however, it is difficult to recognize fine, ironic allusions in a text in another language. You run the risk of interpreting clichés and reading stereotypes .

If one does not accept a pun, the meaning is different. In the ancient Orient, the shadow of a deity was associated with a protective and preserving effect. It is an integral part of the ancient oriental royal ideology. According to Schipper, the passage means nothing else than that Wenamun comes under the protection of the "Pharaoh". The designation as pharaoh only expresses that Wenamun is under very special protection and does not mean the qualification of the prince as pharaoh.

Missing end

It was widely believed that a third page of the papyrus was missing at the end of the narrative. In any case, the short end of such an extensive story is astonishing. Elke Blumenthal suspects that "further adventures of the hero and his return to Egypt were reported". Bernd U. Schipper thinks it is also possible that this end was intended, because “the problems have been solved and it is clear that Wenamun will get back to Egypt safely”, which means that it is a piece of literature “that is deliberately kept open in order to give the reader the opportunity to continue telling the story and make it their own ”. Friedrich Haller sees it similarly: “A final sentence about the happy homecoming, if one had missed him, could easily have found a place on the papyrus. Why should the scribe who wrote the very long story have put down the brush shortly before the end? "

Interpretations

Historicity and fictionality

Since the beginning of research into the text, views on historicity and fictionality have diverged widely, and a wide range of interpretive approaches was available early on. For a long time the central question was whether it was a real factual report or a fictional work of literature. In 1900, Adolf Erman and W. Max Müller saw the text as a factual report with little literary character, as an original or a record-based copy of a report in which Wenamun wanted to justify his unsatisfactory success of the company.

As early as 1906, Alfred Wiedemann answered the question of the literary character completely differently and considered the text to be fictional literature and an adventure story. Even Gaston Maspero was followed this view, pointing out the importance of the god Amun.

In 1952 Jaroslav Černý referred to two points in favor of an administrative document: the non-literary language and the direction of writing across the fibers of the papyrus. Many Egyptologists followed this view and the narrative has therefore often been used as the main historical source.

Elke Blumenthal assessed the literary character differently again in 1982:

“The dialogues are probably literary fiction, perhaps even the figure of Wen-Amun, but the experiences described here were undoubtedly made by Egyptian travelers, and so the basic narrative contains more historical truth than the success stories the official travel reports and as the political historiography, the trade relations to vassal relationships and goods to tributes reinterpreted. "

Wolfgang Helck in particular questioned Černý's arguments in 1986 and as a result the text was again largely regarded as literary: The fact that the text is written in the manner of an administrative text does not hide its literary character. Despite the good knowledge of the Syrian conditions at the time, this would be the only larger text that delivers a report based on real events. For example, The Story of Sinuhe is also a political text. In addition, the papyrus containing the Wenamun story was not found as part of an official archive, but rather in a small library.

In general, for Antonio Loprieno it is a sign of fictional creation when a text appears outside of its given framework - for example, the story of Sinuhe, which is presented as an autobiographical grave inscription, appears outside of the grave context, and the Wenamun story lacks a direct reference for administration, as it was found together with two other literary papyri.

In 1999 John Baines did not consider it possible to assign the text to a genre due to the direction of writing, but saw the fact that the papyrus was written on pieces that were glued together as atypical for an administrative document: The “greatest distinguishing feature of the type of inscription seems to be the use of different ones being separate pieces of papyrus rather than a single roll. That is not the normal practice with official documents. "

Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the narrative is based on actual events and that an orally narrated original has been literarily expanded. An inscription by Herihor in the Temple of Chon in the Karnak Temple shows that during the Wehem-Mesut era Ramses XI. actually a new barge was built for the god Amun from Lebanon cedar wood. In the Papyrus Berlin 10494 of the Late Ramesside Letters , which presumably dates to the year 2 of the Wehem-mesut era, a person named Wenamun is listed, the name being spelled exactly as in the Wenamun story. The text mentions that Wenamun was under the supervision of Betehamun, who in turn was closely associated with Herihor. Thus Wenamun named in the list could actually have been the envoy sent by Herihor.

In Russian research, the main view was that it was a narrative based on real events that were subsequently embellished.

Travel motive and international experience

Antonio Loprieno examined the relationship between the two poles of social expectation and individual experience on the basis of the foreign motif and sees foreign countries as the main component in the story of Wenamun (and for the outgoing New Kingdom in general), from which Egypt's crisis of meaning can be read: “not foreign countries only take part in the narrative, they shape it directly ”. In the post-Ramessid period, foreign countries are the variable “by which the Egyptian world of meaning can read and establish its own crisis”, Wenamun proclaims “through his humiliating experience in Lebanon, in literary terms, the extent of the social and political crisis in the Egyptian world of meaning”.

Gerald Moers assigned the Wenamun story to the genre of "travel literature", in which the "type of wanderer and seafarer, in the first person subjunctive and abruptly reports on his own experiences and experiences". He contrasted this genre with the larger part of the Egyptian stories, in which the author describes in the third person and mostly only takes part in the events narrative. It is limited to a few works such as The Story of Sinuhe , the Letter of Wermai , the Story of the Shipwrecked and the Story of Wenamun. Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert considers the term “travel literature” to be inappropriate, as the hero does not act on his own initiative and does not travel to get to know foreign places and regions. Nevertheless, in his opinion, travel reports by returnees from the Levant may have had an impact on the story.

According to Gerald Moers, the function of foreign countries as a "schema of reflection" in the Sinuhe story differs significantly from that in the Wenamun story. In contrast to Sinuhe, who flees abroad in order to experience his identity as an Egyptian in the mirror image of the foreign country and who returns successfully, Wenamun suffers a loss of identity. Wenamun no longer reaches the point from which he started; The starting point and destination of his journey are no longer identical.

Religious-political message

Wolfgang Helck suspected a fictional creation in Wenamun's travelogue, the purpose of which is to demonstrate the power of the god Amun beyond the country's borders: but to 'prove' a very realistic narrative. "

Bernd U. Schipper assumed that an orally told story at the time of Scheschonq I. was developed into a complex work of literature. It was no longer about a temple official who procured timber, but about a religious-political message: “The literary analysis showed that the meaning of the god Amun and his work in the text is clearly unfolded in opposition to the actions of the human envoy Wenamun . [...] Wenamun as a human messenger must fail so that the work of the god Amun-Re can come to light all the more clearly. "

Wenamun has to learn painfully that in the Syrian-Palestinian area the actual power no longer lies with the pharaohs, but with local city rulers, whereby the text on this point reflects the actual political conditions in this area at the end of the New Kingdom. However, this is contrasted with Amun's claim to power: “Even if the pharaohs no longer have any de facto power in Syria / Palestine, that of the god Amun still exists. [...] The text ultimately formulates a religious-political claim which realpolitics first had to be caught up with. "

The gap between Egypt's political claims at the time and reality was cleverly exploited as a moment of tension. In its drafting, the narrative was deliberately placed in the area of tension between historical report, literary narrative, and religious and political intention.

literature

Editions

- Alan Gardiner : Late-Egyptian Stories. (= Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca . Volume 1). Édition de la Fondation égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Brussels 1932; 1981 = reproduction of the 1932 edition, pp. 61–76. ( Online , as a zip file to download)

- Wladimir Semjonowitsch Golenishchev (Wladimir Golénischeff): Papyrus hiératique de la Collection W. Golénischeff, contant la description du voyage en Phénicie. Bouillon, Paris 1899, pp. 74-102.

- Михаи́л Алекса́ндрович Коросто́вцев: Путeшecтвиe Ун-Амуна в Библ . 1960 ( Michail Alexandrowitsch Korostowzew : Die Reise des Wenamun nach Byblos. 1960.) ( online ) In particular Chapter 6 with Korostowzew's hieroglyphic transcription and Chapter 7 with the photographic publication of the hieratic text.

- Georg Möller: Hieratic reading pieces for academic use. 2nd issue. Literary texts of the New Kingdom. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1927; Reprint: Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1961.

Translations

- Elke Blumenthal : Ancient Egyptian travel stories. Reclam, Leipzig 1982, 1984, pp. 27-40 (translation), pp. 47-52 (notes).

- Elmar Edel : The travelogue of the Wn-'mn. In: Kurt Gallig (Ed.): Text book on the history of Israel. 2nd, revised edition, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1968, pp. 41-48.

- Miriam Lichtheim : Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press, Berkley 1976, ISBN 0-520-03615-8 , pp. 224-230. ( Preview of the book ).

- Gerald Moers : Wenamun's travel story . In: Otto Kaiser : Texts from the environment of the Old Testament . (TUAT), Volume 3: Wisdom Texts, Myths and Epics. Delivery 5. Myths and Epics. Mohn, Gütersloh 1995, pp. 912-921, ISBN 3-5790-0082-9 .

- Edward F. Wente, in: William K. Simpson (Ed.): The Literature of Ancient Egypt. An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry. Yale University Press, Cairo 2003, ISBN 978-977-424-817-7 , pp. 116-124 ( online ).

- Bernd U. Schipper : The expedition of the Wen-Amūn (1071?). In: Manfred Weippert (Hrsg.): Historical text book for the Old Testament (= floor plans for the Old Testament. Volume 10). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-51693-5 , No. 100, pp. 214-223

General overview

- Günter Burkard , Heinz J. Thissen : Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history II. New Kingdom. Lit, Münster 2008, 2009, ISBN 3-8258-0987-0 .

- Hans Goedicke : The Report of Wenamun. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore 1975, ISBN 0-8018-1639-4 .

- Wolfgang Helck : Article Wenamun. In: Wolfgang Helck, Wolfhart Westendorf (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Volume VI. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1986, Sp. 1215-1217.

- G. Höber-Kamel: The Adventures of Wen-Amun. In: Kemet. No. 9, Berlin 2000, ISSN 0943-5972 .

- M. Коростовцев: Путeшecтвиe Ун-Амуна в Библ. 1960 (M. Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960.)

- Antonio Loprieno (Ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms (= Problems of Egyptology. Volume 10). Brill, Leiden / New York / Cologne 1996, ISBN 90-04-09925-5 ( preview of the book ).

- Bernd U. Schipper: The story of Wenamun - A literary work in the field of tension between politics, history and religion (= Orbis biblicus et orientalis. (OBO) No. 209). Freiburg 2005, ISSN 1015-1850 .

Individual questions

- John Baines : On Wenamun as a Literary Text. In: Jan Assmann , Elke Blumenthal (Hrsg.): Literature and politics in Pharaonic and Ptolemaic Egypt. Lectures of the conference in memory of Georges Posener 5.-10. September 1996 in Leipzig. Institut français d'archéologie orientale (IFAO), Cairo 1999, ISBN 2-7247-0251-4 .

- John Baines: On the background of Wenamun in inscriptional genres and in topoi of obligations among rulers. In: Günter Burkard, Dieter Kessler u. a .: Texts, thebes, sound fragments. Festschrift for Günter Burkard (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 76). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-447-05864-3 .

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Tanis and Theben. Historical foundations of the Ramesside period in Egypt (= Egyptological research. Volume 16). Augustin, Glückstadt 1951.

- Arno Egberts: Hard Times: The Chronology of “The Report of Wenamun” Revised. In: Journal of Egyptian Language and Antiquity. No. 125, 1998, pp. 93-108. ( Online ).

- Christopher J. Eyre: Irony in the Story of Wenamun: the Politics of Religion in the 21st Dynasty. In: Jan Assmann, Elke Blumenthal (ed.): Literature and politics in Pharaonic and Ptolemaic Egypt. Lectures of the conference in memory of Georges Posener 5.-10. September 1996 in Leipzig (= Bibliothèque d'Étude. Volume 127). Publication de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire (IFAO), Cairo 1999, pp. 235-252.

- Adolf Erman : A trip to Phenicia in the 11th century BC. In: Journal of Egyptian Language and Antiquity. No. 38, Berlin 1900, pp. 1-14. ISSN 0044-216X ( online ).

- Wladimir Semjonowitsch Golenishchev (Wladimir Golénischeff): Open letter to Professor G. Steindorff. In: Journal of Egyptian Language and Antiquity. No. 40, Berlin 1902/1903 , ISSN 0044-216X .

- W. Голенищев: Гиератический папирус из коллекции В. Голенищева, содержащий отчет о путешествии египтянина Уну-Амона в Финикию (Сборник отчет о путешествии Рорнина Уну-Амона в Финикию (Сборник отчет остатей Рорник). 1897. (Vladimir Golenishchev: Hieratic papyrus from the collection of W. Golénischeff, containing an account of the journey of the Egyptian Wenamun to Phenicia. Compilation of articles by students of Professor WR Rosen. Petersburg 1897.)

- Ronald J. Leprohon: What Wenamun Could Have Bought: The Value of his Stolen Goods. In: GN Knoppers, A. Hirsch (Ed.): Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World. Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford. Brill, Leiden 2004, pp. 167-77, ( Online ( Memento from July 26, 2004 in the Internet Archive ); PDF; 37 kB).

- Antonio Loprieno: Topos and Mimesis. To the foreigner in Egyptian literature. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-447-02819-X .

- Antonio Loprieno: Travel and Fiction in Egyptian Literature. In: D. O'Connor, S. Quirke (Ed.): Mysterious Lands (= Encounters with Ancient Egypt. ). University College, London 2003, ISBN 978-1-84472-004-0 .

- Gerald Moers: The departure into the fictional. Travel motif and border crossing in stories of the Middle and New Kingdom. Brill, Leiden 1996, 2001, ISBN 90-04-12125-0 ( mostly online ).

- Benjamin Sass: Wenamun and his Levant - 1075 BC or 925 BC? In: Egypt and Levant. No. 12, Vienna 2002, ISSN 1015-5104 ( online ).

- Renaud de Spens: Droit international et commerce au début de la XXIe dynasty. Analysis juridique du rapport d'Ounamon. In: N. Grimal, B. Menu (Ed.): Le commerce en Egypte ancienne (= Bibliothéque d'étude. [BdE] Volume 121). Cairo 1998, pp. 105-126, ( online ).

- Б. А. Тураев: Египетская литература. 1920 ( Boris Alexandrowitsch Turajew : Ägyptische Literatur. 1920.).

- Anja Wieder: Ancient Egyptian Tales. Form and function of a literary genre. Doctoral thesis in Egyptology, Philosophical Faculty at Ruprecht Karls University, July 9, 2007. ( Online ).

Web links

- reshafim: Wenamen's Journey (English translation)

- Serge Rosmorduc, Patricia Cassonnet: Les mésaventures d'Ounnamon ( Memento of February 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (Hieroglyphic transcription)

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae: Wenamun (transcription and German translation)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b B. U. Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 325 ff.

- ↑ Mikhail Alexandrowitsch Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 5 and BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 5 f.

- ↑ E. Graefe: Article El Hibe. In: Lexikon der Ägyptologie, Volume II. 1977, pp. 1180 ff.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 320.

- ↑ Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 7.

- ↑ GA Wainwright: El Hibah and esh Shurafa and Their Connection with Herakleopolis and Cusæ. In: Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte (ASAE). No. 27, 1927, p. 79.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 323.

- ↑ Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 5.

- ↑ A. Erman: A trip to Phenicia in the 11th century BC. Chr. In: Journal of Egyptian language and archeology. (ZÄS) No. 38, p. 1.

- ↑ Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 20ff.

- ^ Alan H. Gardiner: Late-Egyptian stories. Brussels 1932, p. XI f.

- ↑ Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 5 and p. 19.

- ↑ Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 24ff. and BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 24ff.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 154.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 164.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 165 and H. Kees: Herihor and the establishment of the Theban state of God. In: News from the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. (NAWG) Vol. II / I, 1936, p. 14.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 165 with reference to Jürgen von Beckerath: Thanis and Theben. Historical bases of the Ramesside period in Egypt. 1951, p. 99 f. and also Karl Jansen-Winkeln: The End of the New Kingdom. In: Journal of Egyptian Language and Antiquity. (ZÄS) No. 119, 1992, p. 25 f.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 165.

- ↑ B. Sass: Wenamun and his Levant - 1075 BC or 925 BC? Vienna 2002, p. 248ff.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 332.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 328.

- ↑ The date of 1st Schemu I mentioned in the papyrus results from an oversight by the writer, according to Günter Burkard, Heinz-Josef Thissen: Introduction to the Ancient Egyptian Literary History, Part 2 . P. 53.

- ↑ In the book of the day , the Qebehu region is mentioned in connection with Crete , among other things .

- ^ Table of contents based on the translations by Lichtheim: Literature, II. P. 224 ff. And BU Schipper: Die Erzählung des Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 103 ff. And his historical commentary, p. 164 ff. As well as the summary of Höber Camel: The Adventures of Wen-Amun. In: Kemet No. 1/2000.

- ↑ Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. The history of the Pharaonic high culture from the early days to the end of the New Kingdom approx. 4000-1070 BC. Chr. 2005, p. 270 f. and also J. van Dijk: The Amarna Period and Later New Kingdom. In: Ian Shaw: The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. 2000, pp. 301ff.

- ↑ Thomas Kühn: Karnak - The temple complex of Amun. The religious and political power center of the Third Intermediate Period. In: Kemet Volume 17, Issue 4, 2008, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Edouard Meyer: God's State, Military Rule and Estates in Egypt. On the history of the 21st and 22nd dynasties. 1928, p. 3 ff.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient Records of Egypt. Historical Documents. From the Earliest times to the Persian Conquest . Vol. IV: The Twentieth to the Twenty-Sixth Dynasties. P. 614 ff.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 127 ff.

- ↑ Michal Artzy: Nomads of the Sea. In: S. Gitin, A. Mazar, E. Stern (Eds.): Miditerranean Peoples in Transition (FS T. Dothan). Jerusalem 1989, pp. 7-21.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 136.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 151 ff.

- ^ BU Schipper: Die Erzählung des Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, pp. 161–163.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 315.

- ↑ B. Sass: Wenamun and his Levant - 1075 BC or 925 BC? Vienna 2002, p. 252 ff.

- ↑ J. Baines: On Wenamun as a Literary Text. Cairo 1999, p. 209 ff.

- ^ E. Blumenthal: Ancient Egyptian travel stories. Leipzig 1982, p. 62 ff.

- ↑ J. Baines: On Wenamun as a Literary Text. Cairo 1999, p. 217 ff.

- ^ Günter Burkard: Metrics, prosody and formal structure of Egyptian literary text. in: Loprieno, AEL, p. 447 ff.

- ↑ Helmut Satzinger: How good was Tjeker-Ba'l's Egyptian? In: LingAeg Lingua Aegyptia. Journal of Egyptian Language Studies. No. 5, Göttingen 1997, p. 176.

- ↑ So z. B. Arno Egberts: Double Dutch in the Report of Wenamun? In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM) No. 172, 1999, pp. 17-22.

- ↑ see Rainer Hannig : Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German. von Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , p. 167.

- ↑ Miriam Lichtheim describes him as a “young man”, Adolf Erman as a “great youth” and EF Wente in the broader sense as a “page”.

- ↑ J. Ebach, U. Rüterswörden: The byblitische ecstatic in the report of Wn-mn and the seer of the inscription of the CCR of Hamath. In: GM No. 20, 1976.

- ↑ J. Ebach, U. Rüterswörden: The Byblitische Ekstatiker in the report of the Wn-Imn and the seers of the inscription of the CCNR of Hamath. In: GM No. 20, 1976, p. 20

- ↑ Martti Nissinen: Article prophecy (Old Orient). In: The scientific Bible lexicon on the Internet (www.wibilex.de). Direct link (Accessed June 12, 2011)

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 207, p. 270.

- ^ H. Bauer: A Phoenician pun in the travelogue of Un-Amun? In: Orientalische Literaturzeitung 28, 1925, pp. 571-572.

- ^ A. Leo Oppenheim: The Shadow of the King. In: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 107, 1947, pp. 7-11.

- ^ CJ Eyre: Irony in the Story of Wenamun: the Politics of Religion in the 21st Dynasty. Cairo 1999, p. 240.

- ^ CJ Eyre: Irony in the Story of Wenamun: the Politics of Religion in the 21st Dynasty. Cairo 1999, p. 235; Caption Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 270.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 203 f.

- ↑ E. Blumenthal: Ancient Egyptian travel stories. Leipzig 1982, p. 52.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 279.

- ^ F. Haller: Refutation of the general assumption that the Wenamun report (Papyrus Moscow No. 26 120) breaks off suddenly towards the end and the conclusion is lost. In: Göttinger Miscellen. (GM) No. 173, 1999, p. 9, see also: E. Graefe: The last line of "Wenamun" and sdr ("strong"), sdr ("secure"). In: GM No. 188, 2002.

- ↑ Adolf Erman: A trip to Phenicia in the 11th century BC Chr. In: Journal of Egyptian language and archeology. (ZÄS) No. 38, 1900, p. 2 ff. And WM Müller: Studies on Near Eastern History II. The original home of the Philistines. The Gelénischeff papyrus. The chronology of the Philistine movement. In: Communications of the Middle East-Egyptian Society. (MVAeG) Vol. 5, No. 1, 1900, p. 28.

- ↑ A. Wiedmann: Ancient Egyptian sagas and fairy tales. 1906, p. 94 ff.

- ^ Gaston Maspero: Les contes populaires de l'Egypte ancienne. 3. édition, entièrement remaniée et augmentée, E. Guilmoto, Paris 1906, pp. 214ff.

- ↑ B. Sass: Wenamun and his Levant - 1075 BC or 925 BC? Vienna 2002, p. 247 with reference to Jaroslav Černý: Paper and books in Ancient Egypt. An inaugural lecture delivered at University College, London, 29 May 1947. London 1952, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ E. Blumenthal: Ancient Egyptian travel stories. Leipzig 1982, p. 63.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Wenamun. In: Wolfgang Helck, Wolfhart Westendorf (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Vol. VI. Wiesbaden 1986, Col. 1215-1217.

- ↑ B. Sass: Wenamun and his Levant - 1075 BC or 925 BC? Vienna 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Antonio Loprieno: Defining Egyptian Literature: Ancient Texts and Modern Theories. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. Leiden / New York / Cologne, 1996, p. 51.

- ↑ J. Baines: On Wenamun as a Literary Text. Cairo 1999, p. 233.

- ↑ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 328f. with reference to Jaroslav Černý: Late Ramesside letters. Brussels 1939, p. 24.

- ↑ Korostowzew: The journey of Wenamun to Byblos. 1960, p. 14 ff. And Turajeff: Ägyptische Literatur. 1920, p. 199 ff.

- ^ A. Loprieno: Topos and Mimesis. To the foreigner in Egyptian literature. Wiesbaden 1988, p. 65.

- ^ A. Loprieno: Topos and Mimesis. To the foreigner in Egyptian literature. Wiesbaden 1988, p. 69.

- ^ Moers: The travel story of Wenamun. In: TUAT III / 5, p. 873.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert: Review of G. Moers, Fingierte Welten. In: Orientalist literary newspaper. (OLZ) No. 99, 2004, p. 414.

- ↑ Gerald Moers: The departure into the fictional. Travel motif and border crossing in stories of the Middle and New Kingdom. P. 273.

- ↑ Helck: Wenamun. In: Lexicon of Egyptology. Vol. VI, p. 1216.

- ^ BU Schipper: The story of Wenamun ... Freiburg 2005, p. 329 ff.