German Bohemia and German Moravians

The term German Bohemia is a collective name for the German-speaking inhabitants of Bohemia or all Bohemian countries as well as for the settlement area of this population group. In the countries of Moravia and Austrian Silesia , which belong to the Bohemian Crown , they spoke of German Moravians and German -Silesians . In the 20th century, the term Sudeten Germans or Sudetenlanders was increasingly coined for these groups .

German-speaking settlers mainly colonized the border areas of Bohemia and Moravia mainly in the 12th and 13th centuries - coming from Old Bavaria , Franconia , Upper Saxony , Silesia and Austria as part of the German settlement in the east . Later, as a result of the Hussite Wars , the plague epidemics and the Thirty Years' War , immigrants from German-speaking areas moved to depopulated areas of Bohemia and Moravia. Other immigrants came from German-speaking regions of the Habsburg Monarchy to Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia as part of internal migration , some of them also came from other-language regions of the Habsburg Monarchy and assimilated to German culture.

Concept history

The names German Bohemia , German Moravians and German Silesia came to the national upheaval in 1848 , simultaneously with the frequent use of the term Czechs gradually in use. In the 20th century the term Sudeten Germans became more common. However, this term in turn meant that other long-established, German-speaking population groups felt excluded. In addition, the terms German Bohemia and German Moravians are more precise than the term “Sudeten Germans” because many settlement areas were located far away from the Sudetes .

Until the end of the Dual Monarchy, German Bohemia and German Moravians, like the inhabitants of the Cisleithan Crown Lands that belong to today's Austria , were mostly perceived as Germans of the Austrian half of the empire and also saw themselves as such, as they could only compete with the Slavs of Old Austria in terms of population in this context . In addition, they felt they were part of the contiguous German-speaking area and thus did not perceive themselves as an ethnic minority . In today's Czech Republic , either the terms “German Bohemia” and “German Moravia” are used in connection with the German minority , but more often one speaks simply of the Germans in the Czech Republic .

history

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

German residents have existed in the Bohemian lands since the Middle Ages. The Přemyslids recruited settlers from Bavaria, Franconia, Upper Saxony, Silesia and Austria to settle the Bohemian and Moravian border areas in the course of German settlement in the east in the 12th and 13th centuries. Charles University in Prague was founded in 1348. From the end of the 18th century, when the Latin language of instruction was replaced by German, until the late 19th century, it was culturally and linguistically German. The prose work Der Ackermann von Böhmen from the 15th century by Johannes von Tepl is often cited as a culturally significant example of the Middle Ages .

For centuries, German Bohemians and Moravians played important roles in the economy and politics of the Bohemian countries. For example, glass production was an industry that was widespread in German-Bohemian regions. An independent German-Bohemian consciousness was not widespread for a long time or it did not play a decisive role in everyday life. The people concerned saw themselves mostly as Bohemians, Moravians, Silesians, subjects of the respective ruling ruler or of the Holy Roman Empire .

The decisive events were the Hussite Wars , the activities of the Bohemian Brothers , the Thirty Years' War , which severely affected the countries of the Bohemian Crown, and the wars of Frederick II against Austria for possession of Silesia , which resulted in the loss of much of this land for Austria and the Bohemian lands ended. The loss meant a weakening of the German element in the Bohemian lands. However, the depopulated areas again attracted German settlers.

The fact that the Bohemian lands were mostly ruled by the German Habsburgs from Vienna , and that the old Bohemian nobility had in fact become insignificant after the battle of the White Mountain , favored the increasing dominance of the German language and culture. Century develop increasing resistance.

The long 19th century

After 1848, when the Czech national movement brought about equality between Germans and Czechs , the Germans living in Bohemia tried to maintain their political and cultural sovereignty, at least in the regions in which they formed the majority. The demands were anchored at the congress in Teplitz in 1848.

In 1867 the equality of Austrian citizens of all nationalities was enshrined in the December constitution , the definitive beginning of the constitutional monarchy. The Reichsgesetzblatt was published in the Czech language as early as 1849. Maintaining German supremacy in the whole of Cisleithanien proved increasingly difficult and ultimately impossible.

From 1868 to 1871 the demands of the Germans in Bohemia and Moravia for a constitutional solution from the Czechs grew louder. The postulate of a closed region sometimes took on forms that demanded that Czech be completely excluded. The demarcation should serve a completely new division of the district areas, which should be administered by offices of the respective nationality.

The division was recorded in the Pentecost program of May 20, 1899, which contained extensive regulations for non-German peoples. In 1900, proposals for the division of Bohemia into a German and a Czech zone followed. In 1903 the German People's Council for Bohemia was founded by the physician Josef Titta , which set itself the task of uniting the divided German parties in Bohemia in order to find a solution to the nationality problem. Although the People's Council was unable to bring about a coalition of German parties, it was considered the most important and influential German protective community in old Austria. Moravian Compensation is the collective name for four state laws passed in 1905, which were supposed to guarantee a solution to the nationality problems between Germans and Czechs in Moravia in order to bring about an Austrian-Czech compensation .

In 1907 the Reichsrat , the parliament of Cisleithania, was elected for the first time according to universal and equal male suffrage. (Some Czech politicians have long disputed the responsibility of the Reichsrat in Vienna for the Bohemian countries, disrupted negotiations by obstructing them and demanding their own parliament in Prague, but ultimately got actively involved in Vienna.) In the course of a new constituency division, the electoral districts of the German and Czech settlement areas as far as possible from each other. In 1909, the German Bifurcation Committee, a private initiative, drew up a draft for the complete division of Bohemia and the creation of the German Bohemia region on this basis.

The fundamental antagonism that the Czechs wanted to govern themselves in Prague, German Bohemians and German Moravians, who were in the minority in this solution, but relied on old Austria, could not be resolved in the monarchy.

Settlement areas and number 1910

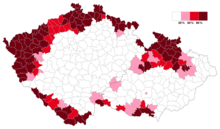

The settlement area of the German Bohemia and German Moravians was geographically distributed in the Bohemian Forest , the Egerland , Northern Bohemia , Eastern Bohemia, Moravian-Silesia , Northern Moravia and Southern Moravia . There were also some German language islands such as the Schönhengstgau (see picture) and German minorities in cities with predominantly Czech-speaking populations.

According to the 1910 census, around 3.25 million Germans (almost a third with a downward trend) out of a total population of just under ten million lived in the Bohemian countries of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy .

Proportions of colloquial languages after the 1910 census:

| Crown land | Residents | German | Czech | Polish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohemia | 6,712,944 | 2,467,724 | 4,241,918 | 1,541 |

| Moravia | 2,604,857 | 719.435 | 1,868,971 | 14,924 |

| Silesia | 741.456 | 325,523 | 180.348 | 235.224 |

| total | 10.059.257 | 3,512,682 | 6.291.237 | 251,689 |

Conflicts over statehood in 1918 and 1919

Projected province of German Bohemia as a desired part of German Austria

On October 28, 1918, Czechoslovakia proclaimed itself an independent state. In the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia and Moravian-Silesia, which are predominantly populated by Germans, the majority of residents refused to be included in the new state. The province of German Bohemia and the province of Sudetenland as well as the districts of Böhmerwaldgau and German South Moravia declared - with reference to the just proclaimed right of peoples to self-determination - their affiliation with German Austria . Czechoslovakia insisted on the "historic lands of the Bohemian crown" and in November 1918 Czech troops occupied these areas. The demonstrations held on March 4, 1919 against it were bloodily broken up by Czech armed forces. The Treaty of Saint-Germain of September 10, 1919 confirmed that the areas inhabited by Germans would remain in Czechoslovakia. The state's own organization was at an end.

The demand for self-determination of the German Bohemians and German Moravians was later taken up again by the Sudeten German Party . The term Sudeten Germans increasingly prevailed in linguistic usage for the German population of the Bohemian countries , although this term was in part not accepted by those affected because they were far away from the Sudeten Mountains, e.g. B. in Prague or in South Moravia, lived ( see also Sudeten Germans ).

First Czechoslovak Republic

During the First Czechoslovak Republic , various political currents , known as negativism and activism , existed within the German-speaking population. For these in turn, the term Sudeten Germans has now become established . This name was derived from the term Sudetenländer , which in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy referred to the countries of the Bohemian Crown. The negativists boycotted the Czechoslovak state, with which they did not identify. In negativistic hand, the German national joined German National Socialist Workers' Party (DNSAP) and the German National Party of Rudolf Lodgman of floodplains in appearance. Opposite these were the farmers ' union , the German Christian Social People's Party , the German Democratic Freedom Party and the German Social Democratic Party on the activist side .

During their existence until 1933, the DNSAP and DNP already approached the NSDAP in Germany more and more ideologically . The Sudeten German home front of Konrad Henlein formed a new nationalist reservoir since October 1, 1933. The Sudeten German Home Front, which later referred to itself as the Sudeten German Party (SdP), increasingly moved closer to the NSDAP and became financially dependent on it. This tendency was also favored by opposing economic developments in the unemployed German-speaking areas of Czechoslovakia and the neighboring, up-and-coming German Empire. Many German-speaking minorities in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia now demanded the connection of their settlement areas to the German Empire. The SdP gained increasing importance in this population group in elections.

On November 5, 1937, Henlein expressed the wish to "incorporate the Sudeten German area, indeed the entire Bohemian-Moravian-Silesian area into the Reich". Finally, under the slogan “ Home in the Reich ”, the Sudeten crisis broke off with the autonomy negotiations with the government in Prague and terrorist activities by the Sudeten German Freikorps culminated in the Munich Agreement.

1938 to 1945

On September 29, 1938, as part of the Munich Agreement, the annexation of the German-speaking areas by the German Reich was decided without the participation of Czechoslovakia . 580,000 Czechs lived in the affected areas. Of these, 150,000 to 200,000 had to leave their places of residence in the direction of central Bohemian and Moravian parts of the country. After integration into the National Socialist sphere of influence, the persecution of Jews, Sinti and Roma and other minorities as well as opponents of the regime began. The Reichsgau Sudetenland , founded on October 30, 1938 under Gauleiter Konrad Henlein, comprised a large part of the German-speaking settlement areas in northern Bohemia and northern Moravia. The other areas were incorporated into neighboring regional authorities in Bavaria and Austria.

On March 15, 1939, in breach of the Munich Agreement, Hitler had the central areas of Bohemia and Moravia, known as “rest of Czechia”, occupied. Hitler declared this territory the " Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ".

From 1939 to 1945, the German-speaking regions of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia shared the history of National Socialist Germany .

expulsion

During and after the capture by American and Soviet troops, many Sudeten Germans fled and there were "spontaneous expulsions " of Germans from the area of former Czechoslovakia. In May, Edvard Beneš propagated the need to remove the Germans, thus triggering a series of sometimes bloody “wild expulsions” through which up to 800,000 people lost their homes. The Beneš decree 108 confiscated all of the German property. In 1946 another 2,256,000 people were officially evacuated.

From the expulsion until today

German minority in the Czech Republic

A small part of the German Bohemians, German Moravians and German Silesians now live as a German minority in the Czech Republic. Most of these remained in the country when they were driven out, as they were seen as necessary to maintain the economy. In 2001 there were still 39,000 German Bohemians, German Moravians and Silesians living in the Czech Republic, who are grouped together as the German minority . The share of the German minority in the total population was 0.4% in 2001. They live mainly in the north and west of Bohemia. Younger generations are sometimes under strong pressure to assimilate the Czech majority population. The numerically largest German minority with 9500 people lives in the northern Bohemian Aussiger region . Almost 3% of the total population of the Czech Republic live in the Karlovy Vary region , and here again the Sokolov district, with 4.5%, is the largest proportion of Germans in the total population.

Displaced persons and their descendants

A far larger number of German Bohemians and German Moravians settled in Germany after the war, where they are more publicly perceived as Sudeten Germans . Some of them also settled in Austria and other countries.

The Germans expelled from Czechoslovakia to Germany after the war and their descendants now live throughout Germany. Here they mainly settled in the area of the former US occupation zone, especially in Bavaria, but also in Hesse and northern Baden-Württemberg . It was here in particular that some companies or cultural institutions were founded, which see themselves in the tradition of formerly Bohemian, Moravian and Silesian institutions and businesses. Displaced towns such as Neutraubling near Regensburg, Neugablonz , Geretsried , Traunreut , Waldkraiburg and Trutzhain , which belong to Kaufbeuren, were newly founded. Other large groups of displaced persons settled in the area of the former GDR . Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia were particularly hard hit. But German Bohemians, German Moravians and their descendants also live in the other areas of the former GDR and in the north of West Germany as well as in Austria. Some of them are organized in the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft or in other organizations such as Ackermann-Gemeinde , Seliger-Gemeinde or Adalbert-Stifter-Verein . The vast majority of this group of people, however, is not a member of a corresponding group and has largely assimilated. Often one can only recognize a Bohemian, Moravian or Silesian ancestry by means of less conspicuous features, including, for example, typical family names, family customs and traditions, dialect colors, an extended family living scattered throughout the German-speaking area or belonging to the mostly Roman Catholic diaspora in the majority Protestant Area or belong to the Old Catholic Church widespread in Bohemia and Moravia .

Dealing with the Munich Agreement and the Beneš Decrees

Despite many friendly contacts on a private or communal level, the relationship between some Czechs and displaced persons from the Sudetenland - and vice versa - is still tense today and in some cases burdened with considerable prejudices. Reconciliation and reconciliation are still problematic and the dialogue between neighbors is still hampered by mistrust on both sides. The Beneš decrees were not declared invalid by the Czech side, contrary to the demands of the expellees' associations.

The fears of many Czechs mainly relate to the possible assertion of property claims should the Beneš decrees be repealed for other former sections of the population. In fact, the Czech people would only have a small part of their own country if they were to B. the claims of the Catholic Church , which called significant parts of the country its own, and those of the former German, Hungarian and Polish landowners, as they were raised immediately after the fall of the 1990/91.

The Federal Republic of Germany initially regarded the Munich Agreement as binding under international law . In contrast, the Czech government has in the past demanded its declaration of invalidity from the outset (legally ex tunc ) as an indispensable prerequisite for the complete repeal of the Beneš decrees. The agreement was later declared null and void ( ex nunc ) in the “normalization treaty” between the Federal Republic of Germany and Czechoslovakia (ČSSR) of December 11, 1973, ratified in 1974 ; the contracting states of the agreement had reached an agreement in 1938 at the expense of a third country, Czechoslovakia.

Since the end of the bloc confrontation , many Czechs have considered the Beneš decrees to be an elementary part of the state's self-image (e.g. President Václav Klaus - although he was so benevolent towards the “German Bohemians” when he took office that he was sometimes very violent Received criticism) - not least for the reasons mentioned. The accession of the Czech Republic to the European Union puts the effectiveness and consequences of the agreement and the decrees on mutual relations into perspective.

Key sentences from the German-Czech Declaration agreed on January 21, 1997 by the governments of both countries :

- From the introduction: "... injustice inflicted cannot be undone, but at best can be alleviated, and that no new injustice may arise ..."

- From paragraph I: "the common path into the future requires a clear word on the past, whereby cause and effect in the sequence of events must not be misunderstood."

- From paragraph II: "The German side ... regrets the suffering and injustice that Germans did to the Czech people through the National Socialist crimes."

- From paragraph III: "The Czech side regrets that after the end of the war, as well as the forced resettlement of the Sudeten Germans from what was then Czechoslovakia, the expropriation and expatriation of innocent people caused a lot of suffering and injustice."

- From paragraph IV: "Both sides agree that the injustice committed belongs to the past and ... that they will not burden their relations with political and legal questions from the past."

- From paragraph VIII: "Both sides ... advocate the continuation of the previous successful work of the German-Czech Commission of Historians."

Current German-Czech relations

In recent years there has been an increasing relaxation in the German-Czech relationship. In the Czech Republic there are initiatives such as the Antikomplex association , which deals with research into the German past of the Bohemian countries. In Ústí nad Labem, the Collegium Bohemicum opened as a scientific institution with the same focus. Documentary filmmaker David Vondráček caused a sensation in 2010 with the documentary Zabíjení po Česku about the expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia. The Sudeten German Landsmannschaft, which is often accused by critics of a rather hostile attitude towards understanding, is making increasing efforts to relax contact with the Czech Republic, especially after the visit of the then Czech Prime Minister Petr Nečas to Bavaria in 2013.

Dialects

In the German areas of the Bohemian countries, the same dialects were spoken as in the neighboring Bavarian, East Franconian, Thuringian-Upper Saxon and Lusatian-Silesian dialect areas:

- Bavarian in the south and west. In detail, Middle Bavarian was spoken in the southern areas along the border with Lower and Upper Austria and in the Bohemian Forest, as well as in the language islands of the Schönhengstgau , Budweis, Wischau , Brünn and Olomouc, as well as North Bavarian along the border with the Upper Palatinate, in the Egerland and in the Iglauer mountains Language island.

- East Franconian or Erzgebirge in the area between the city of Saaz and the Erzgebirge and in language enclaves in Schönhengstgau and in northern Moravia

- Lusatian - Silesian in Northern and Eastern Bohemia (including Upper Lusatian dialect and Glätzischer dialect ) and Northern Moravia ( mountain Silesian ).

- Thuringian-Upper Saxon in sections along the border with Saxony in the area of the Elbe and as a mixed dialect with Northern Bavarian in the Iglauer Sprachinsel and in Prague .

The dialects of the German-Bohemian and German-Moravian regions were lexicographically recorded and described in the Sudeten German dictionary . Linguistic geography is recorded in the atlas of historical German dialects in the Czech Republic . Since there is no longer a closed German-Bohemian and German-Moravian settlement area, some of these dialects are acutely threatened with extinction. This applies in particular to the Silesian dialects and the vernaculars of the former language islands.

literature

- Wilhelm Weizsäcker : Source book for the history of the Sudetenland , Volume I: From primeval times to the renewed state regulations (1627/1628) , Lerche, Munich 1960 DNB 455444889 .

- Karl Bosl : Handbook of the history of the Bohemian countries. 4 volumes, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1966–1971, ISBN 3-7772-6602-7 .

- Emil Franzel : Sudeten German history. Mannheim 1978, ISBN 3-8083-1141-X .

- Hermann Raschhofer, Otto Kimminich: The Sudeten Question. Your development under international law from the First World War to the present. 2nd, supplemented edition, Olzog, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7892-8120-4 .

- Walter Kosglich, Marek Nekula, Joachim Rogall (eds.): Germans and Czechs. History - culture - politics. - With a foreword by Václav Havel (= Beck series. Volume 1414). Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-45954-4 (In Czech: Češi a Němci. Dějiny - Kultura - Politika. Slovo úvodem: Václav Havel. Paseka, Prague 2001, ISBN 80-7185-370-4 ).

- Robert Luft u. a. (Ed.): Ferdinand Seibt - Germans, Czechs, Sudeten Germans. Festschrift for his 75th birthday. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56675-X ( urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00092911-0 ).

- Rudolf Meixner: History of the Sudeten Germans. Preußler, Nuremberg 1988, ISBN 3-921332-97-4 .

- Friedrich Prinz (Ed.): German history in Eastern Europe: Bohemia and Moravia. Siedler, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-88680-773-8 .

- Julia Schmid: "German Bohemia" as a construct of German nationalists in Austria and the German Empire. In: Bohemia . Volume 48, 2008, No. 2, pp. 464-479 ( digitized version ).

- Ferdinand Seibt : Germany and the Czechs. History of a neighborhood in the middle of Europe. 3rd edition, Piper, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-492-11632-9 .

- Tomáš Staněk : internment and forced labor. The camp system in the Bohemian countries 1945–1948 (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum. Volume 92). Oldenbourg / Collegium Carolinum, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-56519-5 / ISBN 978-3-944396-29-3 ( urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00092903-6 ; Original title: Tábory v českých zemích 1945–1948 , translated by Eliška and Ralph Melville, supplemented and updated by the author, with an introduction by Andreas R. Hofmann).

- Tomáš Staněk: Persecution 1945. The position of the Germans in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia (outside the camps and prisons) (= book series of the Institute for the Danube Region and Central Europe . Volume 8). Translated by Otfrid Pustejovsky, edited and partially translated by Walter Reichel. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-205-99065-X .

Today the Collegium Carolinum is the outstanding research institution for joint German-Czech history and publisher of other important literature.

Web links

- Katrin Bock: October 28, 1918. In: Radio Praha , October 26, 2002

Individual evidence

- ^ Antonín Měšťan: Bohemian national consciousness in Czech literature. In: Ferdinand Seibt (Ed.): The chance of understanding. Intentions and approaches to supranational cooperation in the Bohemian countries 1848–1918 . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-53971-X , pp. 31-38, here p. 35.

- ^ Friedrich Prinz (ed.): German history in Eastern Europe: Böhmen und Moravia , Siedler, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-88680-773-8 . (Part of a ten-volume complete work)

- ↑ Manfred Alexander: Small history of the Bohemian countries , Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-010655-6 .

- ^ Alex - Historical legal and legal texts online, website of the Austrian National Library

- ↑ a b c The results of the census of December 31, 1910 in the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council. 1. Booklet: The summary results of the census.

- ↑ Peter Glotz : The expulsion. Bohemia as a lesson. Munich 2003, p. 119.

- ↑ Alena Mípiková, Dieter Segert: Republic under pressure , Federal Agency for Civic Education , November 6th of 2002.

- ^ Speech by MP Sandner on June 25, 1935

- ↑ Statistics: Unemployed 1933–1939 , LeMO website , accessed on March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Helmuth KG Rönnefarth / Henry Euler / Johanna Schomerus, conferences and treaties. Contract Ploetz, a handbook of historically significant meetings and agreements. Part II / Vol. 4 (most recent time 1914-1959) , 2nd exp. u. change Ed., Ploetz, Würzburg 1959, p. 154.

- ↑ Ralf Gebel: "Heim ins Reich!", Konrad Henlein and the Reichsgau Sudetenland (1938–1945) , Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2000, p. 278. Matthias Lichter, Senior Government Councilor in the Reich Ministry of the Interior, wrote in his 1943 at Carl Heymanns Verlag Berlin published work The Citizenship Law in the Greater German Reich to Section 2 of the Treaty between the German Reich and the Czechoslovak Republic on Citizenship and Options Issues of November 20, 1938 ( RGBl. II p. 896), concerning the possibility of one granted until July 10, 1939 Mutual population exchange at the request of the other government: "Incidentally, on March 4, 1939, it was additionally agreed between the Reich government and the then Czechoslovak government that - subject to a different agreement - both sides would not apply § 2 for the time being."

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch, History of the Czechoslovak Republic , Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1978, p. 168.

- ^ Sudeten Germans outraged by Václav Klaus ( Memento of May 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (NetZeitung, June 7, 2005); Declaration by the President of the Czech Republic Václav Klaus on the German-Czech relationship ( Memento of November 18, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (KAS, March 2003).

- ^ Anti-complex

- ^ Collegium Bohemicum

- ↑ “Killing the Czech Way” - a controversial film about mass murders after May 8, 1945 , Radio Praha , May 6, 2010.

- ↑ Zabíjení po česku , Video, Česká televize

- ^ Nečas regrets the expulsion of the Sudetes , report on Petr Nečas' speech in the Bavarian state parliament, SRF, February 21, 2013.