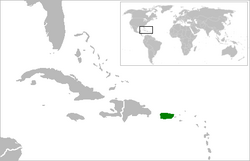

Puerto Rico fauna

The fauna of Puerto Rico , like the fauna of other archipelagos, is rich in endemic species. Bats are the only surviving native land mammals in Puerto Rico . All other land mammals found today, such as cats , small mongooses , domestic goats and sheep , were introduced by humans. Dolphins , manatees and whales also live in the sea belonging to the archipelago . Of the 349 bird species, around 120 breed on the archipelago , 47.5% of the species have only rarely or even only been identified as random visitors. Probably Puerto Rico's most notable and famous animal is the cave whistling frog, or coqui, a small endemic species of frog that is one of the 85 species of herpetofauna . There are no native fish in the fresh waters , although some species have been introduced by humans. Most of the species found are invertebrates .

The arrival of the first humans 4,000 years ago, and to an even greater extent that of Europeans 500 years ago, had a profound impact on the Puerto Rican fauna. Hunting , habitat destruction and the introduction of alien species led to the extinction or local extinction of some species. Conservation and conservation efforts, especially for the Puerto Rican Amazon , began in the second half of the 20th century. In 2002 there were 21 endangered vertebrate species (two mammals, eight breeding birds, eight reptiles , and three amphibians ).

Origin of the fauna of Puerto Rico

The Caribbean plate , on which Puerto Rico and the Antilles - with the exception of Cuba - are located, was formed in the Mesozoic . After Rosen, a volcanic archipelago, the so-called "Proto-Antilles", formed when South America split off from Africa . This archipelago later split into the Greater and Lesser Antilles, which still exist today, due to a new fault . Geologically, the Puerto Rico archipelago is young, as it only formed about 135 million years ago. Nowadays, Howard Meyerhoff's hypothesis is based on the assumption that the Puerto Rican bank, consisting of Puerto Rico, its offshore islands and the Virgin Islands , with the exception of Saint Croixs , were formed by volcanism in the Cretaceous period .

To this day, there is still disagreement about when and how the ancestors of the vertebrates colonized the Antilles. In particular, it is debatable whether the Proto-Antilles were islands in the ocean, or whether they once formed a land bridge between South and North America . The first and prevailing model favors an overwater spread of primarily South American species; The other theory is based on a emanating from the proto-West Indian fauna speciation from. Hedges et al. conclude that species distribution was the primary origin of species in the Caribbean islands . For example, genera like Eleutherodactylus were widespread before a species emerged. On the other hand, insectivores such as Nesophontes sp. and Solenodon marcanoi colonized the Caribbean islands earlier using other methods of dispersion. Woods provides evidence to support this thesis. If one analyzes the arrival of the ancestors of the Antillean tree rats and sting rats , it turns out that the first sting rats must have reached the Greater Antilles either by jumping over from the Lesser Antilles or by swimming in Puerto Rico or Hispaniola .

Alternatively, MacPhee and Iturralde suggest that the first animals of the land mammal tribe reached the Proto-Antilles in the Tertiary at the transition from the Eocene to the Oligocene . At that time, a land mass called "GAARlandia" (Greater Antilles + Aves Ridge land) existed for about 1 million years, connecting the northwest of South America with Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Then the different species would have developed during the break-up of the Proto-Antilles.

The last major changes in the Puerto Rican fauna occurred 10,000 years ago, with the rise in sea levels after the Ice Age and the associated environmental changes. Puerto Rico's transformation from a dry savannah landscape to the current moist, wooded state led to massive extinctions of species, especially among vertebrates. During this time, the connected Puerto Rico bank was also dissolved into individual islands.

Mammals

Puerto Rico, like many other Caribbean islands, had a small number of mammal species compared to the American mainland, but a high proportion of endemics. In addition to Puerto Rico's 18 marine mammals, such as manatees, dolphins and whales. The original land mammal fauna now only consists of 13 bat species. Three other leaf noses have become extinct ( Macrotus waterhoussii , Monophyllus plethodon , and Phyllonycteris major ). All other land mammals originally living here have also died out. Including the largest species of Caribbean shrews the Puerto Rico shrew ( Nesophontes edithae ), five exceptional Rodents: A Riesenhutia ( Elasmodontomys oblique ), a tree rat ( Isolobodon portoricensis ) and three echimyidae ( Heteropsomys antillensis , Heteropsomys insulans , Puertoricomys corozalus ). The two-toed sloths endemic to Puerto Rico are also extinct. Hunting and habitat changes by humans, as well as introduced species are discussed as causes of extinction. However, some researchers believe that these species became extinct because they could not adapt quickly enough to environmental changes after the Ice Age.

The vast majority of land mammals living in Puerto Rico today were introduced by humans. The first settlers introduced dogs and guinea pigs from South and Central America . Later Taínos introduced tree rats (hutias) from Hispaniola as a food source. With the colonization by the Spaniards in the early 16th century, domesticated animals such as cats, domestic goats, pigs, domestic cattle , horses and donkeys were added. Other species such as the house rat ( Rattus rattus ), the brown rat ( Rattus norvegicus ) and mice ( Mus sp. ) Were accidentally introduced as stowaways. More recently, animals have also been introduced for biological pest control . For example, the little mongoose ( Herpestes javanicus ) was introduced in the 19th century to get the damage to sugar cane under control. However, the rats were not decimated as intended, but the local fauna and especially the yellow-shouldered blackbird Agelaius xanthomus were badly affected.

As part of an evolutionary adaptation study , 57 rhesus monkeys were introduced to Desecheo Island and other southern islands and reefs in 1967 . Before its introduction, Desecheo was one of the largest breeding grounds for the brown booby ( Sula leucogaster ). Nowadays, due to the egg robbery by the monkeys, no species of birds breed on the island. Efforts to remove the monkeys failed and they have meanwhile expanded their range to the southwest of Puerto Rico. But other primates have established populations in Puerto Rico as well. In the late 1970s, 107 squirrel monkeys escaped from a research station near Sabana Seca as a result of vandalism . The latest estimates assume that this population now consists of 35 individuals.

Probably the most famous marine mammals of Puerto Rico are the Caribbean manatees ( Trichechus manatus manatus ). The waters of the archipelago are part of the main breeding areas of this species. Manatees are very popular and culturally anchored in Puerto Rico. There is a song by Tony Croatto in which he sings about an animal raised by humans. The municipality of Manatí (Spanish for manatee) is said to be named after the animals.

The waters around Puerto Rico are also an important breeding ground for humpback whales in the northern hemisphere during winter . Humpback whale watching is also a popular tourist attraction.

Bats

The 13 surviving species of bats are five different families to: hare mouths (Noctilionidae) mormoopidae (Mormoopidae), leaf-nosed bat (Phyllostomidae) Myotis bats (Vespertilionidae) and free-tailed bat (Molossidae). In addition, six of the species are endemic to the archipelago. A total of seven species are insectivores, four are frugivores and one species each feeds on fish or nectar . Compared to other parts of the Greater Antilles, 13 species are relatively few. By comparison, 21 species live in Jamaica , i.e. 1.6 times as many, although the area is only about 1.2 times larger. One possible explanation for this is that Jamaica is closer to the mainland or can be reached via Cuba for species from the mainland.

Bats play an important role in Puerto Rico's forest and cave ecology and help keep mosquito populations under control. Ten of the 13 species are cave dwellers with low reproduction rates. The area with the highest species density is in the Caribbean National Forest , where eleven species occur. The fruit-eating red fruit vampire ( Stenoderma rufum) endemic to the Puerto Rico Bank is the only species that spreads the seeds of the balata trees ( Manilkara bidentata ) in the Dacryodes excelsa forest on the Luquillo Mountains , and is therefore very important for this ecosystem. The guano produced by the bats ensures species-rich cave ecosystems, as many of the invertebrate cave dwellers are either guano or scavengers, saprophages or hunters of the same.

The bat species found in the Puerto Rico archipelago are:

- Artibeus jamaicensis

- Brachyphylla cavernarum

- Eptesicus fuscus

- Erophylla sezekoni bombifrons

- Lasiurus borealis

- Molossus molossus

- Monophyllus redmani

- Mormoops blainvillei

- Noctilio leporinus

- Pteronotus parnellii

- Pteronotus quadridens

- Stenoderma rufum

- Tadarida brasiliensis

Birds

Puerto Rico's avifauna is made up of 349 species, 16 of which are endemic to the archipelago. Almost half of the species (166) are random visitors , so they have only been sighted once or twice. 42 species are considered neobiota and were introduced either directly or indirectly by humans. An estimated 120 species also breed regularly on the archipelago.

The avifauna of West India has predominantly North American (southern North America and Central America) origin. However, more recently aggressive South American species have colonized the area. The South American families that occur in the Greater Antilles are hummingbirds (Trochilidae), tyrants (Tyrannidae), sugar birds (Coerebidae) and tanagers (Thraupidae), all of which have representatives in Puerto Rico. The currently prevailing theory assumes that the birds colonized the West Indies across the ocean during the Ice Ages in the Pleistocene . The most primitive birds of West India are the Todis , which are present in Puerto Rico with an endemic species, the Todus mexicanus .

Puerto Rico's avifauna has been greatly reduced in size due to extinction and extinction, partly due to natural influences, partly due to human influences. For example, fossils of a sailor , Tachornis uranoceles , have been found that can be classified as belonging to the late Pleistocene . It is believed that the way due to habitat change after the Würm extinct. At least six endemic species have died out in the last millennium: Puerto Rican barn owl (Tyto cavatica) , a crested caracara species (Polyborus latebrosus ), Puerto Rican parakeet (Aratinga (chloroptera) maugei ), Puerto Rican woodcock (Scolopax anthonyi ), Puerto Rican pigeon ( Geotrygon larva ) and a presumably flightless rallen species ( Nesotrochis debooyi ). In 1975 the Puerto Rico Amazon threatened to become the seventh species with only 13 representatives left. But it could be saved by protective measures. Nevertheless, it is still considered one of the ten most threatened bird species in the world. In addition, the Haitian parakeet , Antilles crow , Cuban crow, and black-wheeled crane were all extinct in Puerto Rico as the population grew in the second half of the 19th century . Three other species, the fall whistled goose , slate rail and Cuban flamingo , no longer breed on the archipelago.

Amphibians and reptiles

Puerto Rico's herpetofauna consists of 24 amphibian and 61 reptile species . The majority of the reptile species of West India are believed to have come to the islands with debris. But there are also indications that support the thesis of allopatric speciation . The rest of the herpetofauna are believed to have reached the West Indies, and thus also Puerto Rico, in the same way and then participated in allopatric speciation. As a result, Puerto Rico, and the entire Caribbean in general , has one of the highest proportions of endemic reptiles and amphibians in the world. The amphibians of Puerto Rico belong to four families: toads (Bufonidae) (2 species), tree frogs (Hylidae) (3), southern frogs (Leptodactylidae) (17) and real frogs (Ranidae) (2). The reptiles include fresh and saltwater turtles , lizards , double snakes , snakes and the crocodile caiman .

All species of Puerto Rico's real frogs and tree frogs were introduced. One species of toad, the cane toad , was introduced, while the other, Bufo lemur , is endemic and endangered. The cane toad was introduced to Puerto Rico in the 1920s to control the population of a beetle of the genus Phyllophaga that was a sugarcane pest. All 17 species of southern frogs are native to the region and 16 species belong to the genus of the Antilles whistling frogs ( Eleutherodactylus ), which are known as Coquís in Puerto Rico. Three Antilles whistling frogs , E. karlschmidti , E. jasperi and E. eneidae , are believed to have died out. E. jasperi is the only viviparous species of the southern frogs and E. cooki is the only Eleutherodactylus species that exhibits sexual dimorphisms in size and color. The Cave Whistle Frog or Coqui (Eleutherodactylus coqui ) is the unofficial national symbol of Puerto Rico and an important part of Puerto Rico's culture. Since 13 of the 16 Coqui species are endemic to the archipelago, a common saying of the Puerto Ricans is: " De aquí como el coquí " (From here [Puerto Rico] like the coquí).

Puerto Rico's turtle fauna consists of five, including two extinct, freshwater turtles and five sea turtles. Two of these ten species, the hawksbill sea turtle and the leatherback turtle are considered endangered. They are particularly threatened by the destruction of their habitats and the robbery of their eggs. The introduced crocodile caiman is the only representative of the crocodile order in Puerto Rico. The largest land-dwelling lizard Puerto Rico is endemic to Mona Iceland living Mona Island Iguana ( Cyclura (cornuta) stejnegeri ). Another Cyclura species of similar size is the Anegada ground iguana (Cyclura pinguis ), which was once at home in the archipelago, but now only as a result of hunting by dogs, cats and humans, as well as habitat destruction and competition from domestic goats and pigs occurs on Anegada .

Puerto Rico's eleven species of snake are considered non-poisonous, although research has shown that at least one species, the Puerto Rican smooth snake (Alsophis portoricensis) , produces venom. The species belong to three families and 4 genera: Typhlopidae ( Thyplops ), Boidae ( Epicrates ) and Colubridae ( Alsophis and Arrhyton ). The largest snake in Puerto Rico is the endemic Puerto Rico boa (Epicrates inornatus ), with a maximum length of 3.7 m. The diet of the snakes in Puerto Rico consists of reptiles ( Ameiva , Anolis , Geckos , Coquís and other frogs) and to a small extent mice, birds and bats, but this only with Epicrates inornatus .

The most common lizard in Puerto Rico is Anolis pulchellus . The Anolis -Echsen Puerto Rico in particular - and the Greater Antilles in general - are an interesting example of adaptive radiation . So are Anolis -Echsen related to the representatives of the same island much closer than neighboring with representatives Islands. Surprisingly, the same habitat specialists have developed on the individual islands.

fishes

The first descriptions of fish in Puerto Rico were published by Cuvier and Valenciennes in 1828. They reported 33 taxa in the archipelago. Puerto Rico itself has no native freshwater fish, but has 24 introduced species, mostly from Africa, South America, and the southeastern United States . Another 60 saltwater fish use the fresh waters of Puerto Rico at times a year. Some of the introductions were made intentionally, and some accidentally. The intentions in introducing the species were sport fishing , nutrition, mosquito control, and bait fish for largemouth bass . Inadvertently introduced species such as the catfish Pterygoplichthys multiradiatus can largely be traced back to released aquarium fish. The Puerto Rican Department of Natural and Environmental Resources has been operating breeding sites near Maricao since 1936 . Around 25,000 fish, including largemouth bass, the cichlid Cichla ocellaris and some turtle species are raised there every year to fill the waters of Puerto Rico.

There are three types of habitats in the marine waters of Puerto Rico: mangroves , coral reefs, and seagrass beds . A total of 667 species of fish live there. 242 of which are reef species . The fish species of the Puerto Rican reefs are representatives of the Caribbean fish fauna. Common reef fish include wrasse , damselfish , the grunt Haemulon plumieri and Haemulon sciurus , the parrotfish Scarus vetula , and requiem sharks (Carcharhinidae). Gerres cinereus and the sea bream Archosargus rhomboidalis and are two typical mangrove inhabitants. Other interesting species include flatfish (21 species), and sharks (> 20). Whitetip deep sea sharks and silky sharks are typical in the Mona Passage .

Invertebrates

The invertebrate fauna of Puerto Rico is rich, but has a lower biodiversity compared to the mainland of the neotropics . Compared to other islands in the Antilles, Puerto Rico is the best-explored area.

Puerto Rico's insect fauna is also considered to be poorly developed compared to the mainland. For example, there are 300 species of butterflies in Puerto Rico , compared to 600 in Trinidad . In Brazil , 1500 species can already be found on 750 hectares . Out of 925,000 insects known in 1998, only 5,573 were found in Puerto Rico. Of the 31 insect orders known worldwide, 27 are represented in Puerto Rico. There are no rock jumpers ( Microcoryphia ), cricket cockroaches (Grylloblattidae), stone flies ( Plecoptera ) and beaked flies ( Mecoptera ) on the archipelago . The largest insect repository in Puerto Rico is located in the Museo de Entimología y Biodiversidad Tropical (Museum of Entomology and Tropical Biodiversity).

Arachnids play an important role in forest ecology, both as predators and as prey. In some forest types, such as the Dacryodes excelsa forest, they are the most important tree-dwelling invertebrate hunters, with spiders (Araneae) as the most common representatives. In the Maricao Commonwealth Forest , 27 species of spiders belong to five families: curled-wheel- web spiders (Uloboridae), quiver spiders (Pholcidae), crested-web spiders (Theridiidae), canopy spiders (Linyphiidae) and true orb-web spiders (Araneidae). From Theotima minutissima , a small one in the Caribbean National Forest frequent spider, it is believed that they are using parthenogenesis propagates.

18 earthworms , eleven of which belong to the Glossoscolecidae family , three to the Megascolecidae and four to the Exxidae , have been described. 78 invertebrates are known to be cave dwellers. Six of these species occur exclusively in the Antilles, 23 are endemic to Puerto Rico and 23 come from North America. Only two species are restricted to life in caves as troglobionts . 45% of the species are hunters, the rest are guanoas, detrivores and herbivores . It is believed that most of this fauna reached Puerto Rico in the Pleistocene.

The marine invertebrate fauna of Puerto Rico consists of 61 sponges , 171 cnidarians , 8 cordworms , 1,176 molluscs , 129 polynesian animals , 342 crustaceans , 165 echinoderms , 131 bog animals , 117 stony corals , 99 soft corals and gorgonians , 13 disc anemones and 8 hydrocorallina s. The coral species found in Puerto Rican waters are representatives of the Caribbean fauna. Typical corals that occur are Montrastaea annularis , Porites porites , and Acropora palmata .

Introduced invertebrates have had an observable impact on the Puerto Rican fauna. Native freshwater snails , such as Physa cubensis , have been adversely affected. Tarebia granifera, imported from Africa, is currently the most common snail in Puero Rico. And the introduced honeybees make life difficult for a native species, the Puerto Rican Amazon, in the competition for nesting sites in the Caribbean National Forest. And the more aggressive Africanized honeybees in terms of nesting sites have recently expanded their range to include Puerto Rico. In addition, 18 species of ants were introduced.

Human influences and nature conservation

Since the Ortoiroids first settled Puerto Rico about 4000 years ago , the country has been exposed to numerous human influences. The native fauna was partly used by the indigenous people as a source of food, other parts were used for clothing and trade. A significant decline in biodiversity and population sizes probably only began with the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. Habitat destruction as a result of deforestation for sugar cane plantations had a decisive and far-reaching impact on fauna in the late 19th century. The previously mentioned introduced, alien animals also had an effect. It is assumed that rats have had a clearly negative impact on the population of Sphaerodactylus micropithecus on the island of Monito . Furthermore, feral cats have been observed hunting sparrow dust and endemic reptiles. They were also associated with the decline of the Cyclura cornuta stejnegeri boys. Mongoose, on the other hand, have been spotted hunting Puerto Rico Amazons.

There are conservation programs both for the country itself and for the individual species. An estimated 895 hectares (3.4% of the total area) are divided into 34 reserves. According to the IUCN, there are 21 endangered species in Puerto Rico: 2 mammals, 8 breeding birds, 8 reptiles, and 3 amphibians. The U.S. federal government lists 5 mammals, 2 amphibians, 8 birds, and 10 reptiles in the Endangered Species Act . The Puerto Rico government has its own list of 3 amphibians, 7 birds, 3 reptiles, 2 fish and 3 invertebrates.

At the moment, the greatest efforts to preserve the species are being made in the area of bird life. Probably the most successful campaign started in 1968 for the Puerto Rico Amazon. The main goals are to establish two viable populations with more than 500 animals of this species by 2020 and to protect their habitats. There are currently 44 parrots in the wild and another 105 in captivity.

The Puerto Rico Breeding Bird Survey (PRBBS), established in 1997, is a program aimed at determining the status and trends of Puerto Rico's bird fauna. The information collected is used by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to prioritize its conservation programs.

The protection of the oceans has also recently taken off in Puerto Rico. The archipelago has an approximately 1126.5 km long coastline and 3370 km² of coral reefs . The Department of Natural Resources of Puerto Rico maintains 25 areas, of which only two are designated as so-called no-take areas. By Earthwatch and federal government programs and an awareness was created that all turtle species in the waters of Puerto Rico are considered threatened. This contributed to a decrease in animal consumption and egg theft.

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles A Woods, Jason H Curtis, Florence E Sergile: Biogeography of the West Indies . CRC, 2001, ISBN 0-8493-2001-1 .

- ↑ Dr. Hans-Joachim Herrmann: Terrarium Atlas 2: Frogs MERGUS Verlag GmbH for nature and pet science. Hans A. Baensch - Melle - Germany

- ^ Caribbean - Human impacts . In: Biodiversity Hotspots . Conservation International. Archived from the original on May 15, 2005. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ↑ a b Biodiversity and protected areas - Puerto Rico (pdf) EarthTrend. P. 1-2. 2003. Archived from the original on October 27, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ↑ Martin Meschede, Wolfgang Frisch: The evolution of the Caribbean Plate and its relation to global plate motion vectors: geometric constraints for an inter-American origin . In: Transactions of the Fifteenth Caribbean Geological Conference . S. 1 .

- ↑ DE Rosen: A vicariance model of Caribbean biogeography . In: Systematic Zoology . tape 25 , 1975, pp. 431-464 .

- ^ A b H. Heatwole, R. Levins, MD Byer: Biogeography of the Puerto Rican Bank . In: Atoll Research Bulletin . tape 251 , July 1981, p. 8 ( PDF [accessed July 30, 2006]).

- ^ S. Blair Hedges, Carla A. Hass, Linda R. Maxson: Caribbean biogeography: Molecular evidence for dispersal in West Indian terrestrial vertebrates . In: Proceeding of National Academic Scientist USA . tape 89 , March 1992, p. 1909-1913 .

- ^ CA Woods: A new capromyid rodent from Haiti: the origin, evolution, and extinction of West Indian rodents, and their bearing on the origin of New World hystricognaths . In: CC Black, MR Dawson (Eds.): Papers on fossil rodents in honor of Albert Elmer Wood . Nat. Hist. Museum, Los Angeles County 1989.

- ^ MA Iturralde-Vinent, RDE MacPhee: Paleogeography of the Caribbean region: implications for Cenozoic biogeography . Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., 1999.

- ^ RDE MacPhee, Manuel A. Iturralde Vinent: Origin of the Greater Antillean Land Mammal Fauna, 1: New Tertiary Fossils from Cuba and Puerto Rico . In: Novitates . No. 3141 , June 30, 1995 ( Digitallibrary [accessed October 26, 2016]).

- Jump up ↑ a b Storrs L. Olson: A new species of Palm Swift ( Tachornis : Apodidae) from the Pleistocene of Puerto Rico . In: The Auk . tape 99 , April 1982, pp. 230–235 ( pdf [accessed on August 3, 2006]).

- ↑ a b c Ernesto Weil: Marine Biodiversity of Puerto Rico: Current Status . Archived from the original on May 23, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2006.

- ↑ Morgan, G. (2001). Patterns of Extinction of West Indian Bats. Pages 369-408 in Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. Boca Raton, Florida.

- ↑ Woods, CA, R. Borroto Paéz, and CW Kilpatrick. (2001). Insular Patterns and Radiations of West Indian Rodents. Pages 335-353 in Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. Boca Raton, Florida.

- ↑ Some researchers assume there are two two-toed sloths , namely Acratocnus major and Acratocnus odontrigonus .

- ↑ Woods, CA (1990). The fossil and recent land mammals of the West Indies: an analysis of the origin, evolution, and extinction of an insular fauna. Pages 641-680 in International symposium on biogeographical aspects of insularity. Rome, Italy.

- ^ A b c d Wiley, James W. and Vilella, Francisco J .: Caribbean Islands . United States Geological Survey . Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ↑ Oficina de Turismo de Manatí ( Spanish ) Municipio Autónomo de Manatí. Archived from the original on July 15, 2006. Retrieved on August 5, 2006.

- ↑ Cuevas, Victor M .: Wildlife Facts - February 2002 - Bats . Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ Robert H. MacArthur, Edward O. Wilson: The Theory of Island Biogeography . Princeton University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-691-08836-5 , pp. 99 .

- ^ Mark Oberle: Las aves de Puerto Rico en fotografías . Editorial Humanitas, 2003, ISBN 0-9650104-2-2 , p. 5 . (span.)

- ^ A b James Bond: Origin of the bird of the West Indies . (PDF) In: Wilson Bulletin . 60, No. 4, December 1948, pp. 210-211. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

- ↑ Evidence also suggests that the fossils date from the Worm Ice Age.

- ^ Lindsey M. Hower and S. Blair Hedges: Molecular Phylogeny and Biogeography of West Indian Teiid Lizards of the Genus Ameiva Archived from the original on May 1, 2004. (pdf) In: Caribbean Journal of Science . 39, No. 3, 2003, pp. 298-306. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- ↑ Jennifer B. Pramuk, Carla A. Hass, and S. Blair Hedges: Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of West Indian Toads (Anura: Bufonidae) Archived from the original on November 20, 2003. (pdf) In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution . 20, No. 2, August 2001, p. 7. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- ↑ Javier A. Rodriguez Robles and Richard Thomas: Venom function in the Puerto Rican Racer, Alsophis portoricensis Archived from the original on August 24, 2006. Information: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (pdf) In: Copeia . 1, 1992, pp. 62-68. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- ↑ Wildlife facts - Sharp-mouthed Lizard . UDSA Forest Service. June 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- ↑ AK Knox, JB Losos, and CJ Schneider: Adaptive radiation versus intraspecific differentiation: morphological variation in Caribbean Anolis lizards Archived from the original on 13 May 2005. (pdf) In: Journal of Evolutionary Biology . 14, 2001, p. 904. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ History of Ichthyology in Puerto Rico . USGS. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- ↑ Parasites of Puerto Rican freshwater sport fishes . Dept. of Marine Sciences, 1994, ISBN 0-9633418-0-4 , pp. 122 ( uprm.edu [PDF]). Parasites of Puerto Rican freshwater sport fishes ( Memento of the original from August 22, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Lucy Bunkley Williams, et al .: The South American Sailfin Armored Catfish, Liposarcus multiradiatus (Hancock), a New Exotic Established in Puerto Rican Fresh Waters. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. In: Caribbean Journal of Science . 30, No. 1-2, 1994.

- ↑ Morton N. Cohen. "The other side of Puerto Rico," The New York Times, April 26, 1987. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- ^ Clive Wilkinson (ed.): Status of coral reefs of the world: 2004 . S. 438 .

- ↑ a b Essential fish habitat assessment - Naval activity Puerto Rico (pdf) p. August 15, 2005. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved on August 4, 2006.

- ↑ a b Alejandro Acosta: Use of Multi-mesh Gillnets and Trammel Nets to Estimate Fish Species Composition in Coral Reef and Mangroves in the Southwest Coast of Puerto Rico Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. In: Caribbean Journal of Science . 33, No. 1-2, 1997. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ↑ Robin Gibson: Flat Fishes: Biology and Exploitation . Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2005, ISBN 0-632-05926-5 , pp. 53 .

- ^ A b Douglas P. Reagan, Robert B. Waide (eds.): The Food Web of a Tropical Rain Forest . University Of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-70600-1 , pp. 190-192 .

- ↑ Puerto Rico's comprehensive wildlife conservation strategy (pdf) Department of Natural and Environmental Resources. S. 1. 2005. Archived from the original on December 23, 2005. Retrieved on August 22, 2006.

- ^ The "Museo de Entimología y Biodiversidad Tropical" of the Agricultural Experimental Station, University of Puerto Rico (pdf; 108 kB). Retrieved on August 11, 2006.

- ↑ Reagan and Waide, p. 267

- ^ Allan F. Archer: Records of the web spiders of the Maricao Forest Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. (pdf) In: American Museum of Natural History . February 1961. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Robert L. Edwards, Eric H. Edwards, and Annabel D. Edwards: Observations of Theotima minutissimus (Araneae, Ochyroceratidae), a parthenogenetic spider . (pdf) In: The Journal of Arachnology . 31, 2003, pp. 274-277. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- ^ Paul F. Hendrix: Earthworm Ecology and Biogeography in North America . CRC, 1995, ISBN 1-56670-053-1 , pp. 76 .

- ↑ Hendrix's (1995) taxonomic classification has been revised, and this article is the revised version.

- ↑ Steward B. Peck: The invertebrate fauna of tropical American caves, Part II: Puerto Rico, an ecological and zoogeographic analysis . (preview) In: Biotropica . 6, No. 1, April 1974, pp. 14-31. Retrieved August 4, 2006.

- ^ Wilkinson, p. 434.

- ↑ Fact Sheet for Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1822) . Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved on August 11, 2006.

- ↑ Reagan and Waide, p. 159-160.

- ^ MA García, CE Diez, and AO Alvarez :: The eradication of Rattus rattus from Monito Island, West Indies . Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ↑ Wiewandt, TA 1975. Management of Introduced Fauna: Appendix to the Department of Natural Resources Management Plan for the Mona Island Unit. USDI Bureau of. Sport Fish and Wildlife. Project W-8-18, Study III. Atlanta. Georgia.

- ↑ Richard Engeman, Desley Whisson, Jessica Quinn, Felipe Cano, Pedro Quiñones, and Thomas H. White Jr: Monitoring invasive mammalian predator populations sharing habitat with the Critically Endangered Puerto Rican parrot Amazona vittata Archived from the original on May 7, 2006. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Oryx . 40, No. 1, August. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ↑ Puerto Rico's wildlife comprehensive strategy, p.2

- ↑ For the complete list, see Apéndice 1. Lista de especies protegidas ( Memento of March 15, 2003 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Technical / Agency Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the Puerto Rican Parrot ( Amazona vittata ) (PDF; 3.7 MB) US Fish and Wildlife Service. April 1999. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- ^ BBS - Puerto Rico . Archived from the original on March 6, 2003. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ Wilkinson, p.435.

- MR Gannon, M. Rogriguez-Duran, A. Kurta, and MR Willig: The Bats of Puerto Rico . Archived from the original on April 21, 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- Placer, José: The Bats of Puerto Rico - Bats have few friends on the island of Puerto Rico, but the dedicated few are working hard for their survival. . . Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. In: Bat Conservation International membership magazine . 16, No. 2, pp. 13-15. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- Mark Oberle: Las aves de Puerto Rico en fotografías . Editorial Humanitas, 2003, ISBN 0-9650104-2-2 (Spanish).

- The Geology of Puerto Rico . Retrieved July 31, 2006.

More reading

- Albert Schwartz: Amphibians and Reptiles of the West Indies: Descriptions, Distributions, and Natural History . University Press of Florida, 1991, ISBN 0-8130-1049-7 .

- Charles L. Hogue: Latin American Insects and Entomology . University of California Press, 1993, ISBN 0-520-07849-7 .

- Juan A. Rivero: Los Anfibios y reptiles de Puerto Rico . University of Puerto Rico Press, San Juan (Puerto Rico) 1998, ISBN 0-8477-0243-X .