Marienberg Fortress

| Marienberg Fortress | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Marienberg Fortress, south side |

||

| Castle type : | Hilltop castle | |

| Conservation status: | Received or received substantial parts | |

| Place: | Wurzburg | |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 47 '23 " N , 9 ° 55' 17" E | |

|

|

||

The Marienberg Fortress is a former fortification and a former prince-bishop's castle on the Marienberg 100 meters above the Main in Würzburg in Lower Franconia . It is also called the fortress of our women mountain . An older name for the complex, which served as the seat of the former government of the Würzburg monastery until the 18th century, was Marienberg Castle .

location

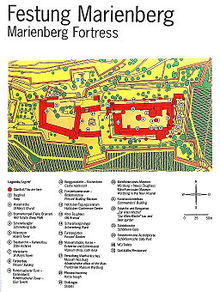

The fortress was built on a mountain tongue on the left side of the Main about 100 meters above the river. The west side is the only flat side of the mountain. On the north side are the gardens and allotments that were laid out in the course of the State Horticultural Show in 1990. The other two mountain slopes are vineyards. The small slope on the eastern flank of the castle is the Schlossberg , on the southern flank the Inner Bar .

history

Fortified settlements were probably located here as early as the late Bronze Age ( Urnfield Culture ) and the Early Iron Age ( Hallstatt Age ). After the Great Migration, the Franks came in the 6th century. At the beginning of the 8th century, the Marienkirche , the oldest church in Würzburg, was built, in which the Würzburg bishops were initially buried, as the tombstones testify to. Below the fortress facing the Main is the town's oldest church in the valley, St. Burkard .

The fortress has been rebuilt several times in the course of history. The oldest surviving parts are from 704 (small Marienkirche).

Around 1200 a castle complex with a keep and a deep well was built, the Palais des Konrad von Querfurt . From 1253 to 1719 Marienberg Fortress was the residence of the Würzburg prince-bishops .

Peasants' War

In 1525, during the Peasants' War , the Marienberg Fortress was defeated without success. For the supporters of Bishop Konrad II von Thüngen , the fortress remained a retreat in the otherwise devastated Diocese of Würzburg , until troops of the Swabian League and an army of the bishop returning from exile defeated the poorly organized farmers. The rebellious farmers suffered a heavy defeat at the gates of the city of Würzburg.

Fortress commander during the siege by the peasants was Provost Margrave Friedrich von Brandenburg (1497–1536). He commanded 18 squads , which were distributed according to plan on different sections of the fortress, in addition, he kept an intervention reserve with him. Rotenhan had drawn the troops together from the castle garrisons of Werneck, Rothenfels, Homburg and Karlburg in good time . There were a total of 400 people at the fortress, of which a little over 240 were capable of carrying weapons. The prominent people included Count Wolf von Castell , Canon Hans von Lichtenstein, Canon Melchior Zobel von Giebelstadt , Hans von Grumbach , Otto Groß , Sigmund Fuchs, Hainz von Stein, Wolf von Fulbach , Matern von Vestenberg , Werner von Stetten , Sebastian Geyer , Lorenz von Hutten , Wendel von Lichtenstein, Andreas Stein von Altenstein, Georg Wemckdinger, Barthel Truchseß , Götz von Thüngen and Philipp Bernheimer. The war council included the court master Sebastian von Rotenhan , Philipp von Herbilstadt , Eustachius and Bernhard von Thüngen , Carl Zöllner, Friedrich von Schwarzenberg , Hans von Bibra and Silvester von Schaumberg . Also present were dean Johann von Guttenberg , Konrad von Bibra and other Würzburg canons .

A small memorial near Tellsteige on the slope of the Marienberg Fortress reminds of the farmers' heaps and their concerns. Tilman Riemenschneider is said to have sided with the farmers as a member of the city council and was therefore imprisoned at Marienberg Fortress for six weeks after the collapse of the uprising. The historic Hof zum Stachel inn in Gressengasse was a meeting place for the revolting citizens and farmers at that time and was recognizable as a pub sign for the initiated on the Morgenstern (Stachelkugel).

Siege in the German Peasants' War

During the German Peasant War in 1525 there were widespread uprisings of the common man in the Würzburg monastery , in which some representatives of the (lower) nobility also took part, for example Count Georg von Wertheim. The then incumbent Prince-Bishop of Würzburg, Konrad II von Thüngen , had already fled on May 6, 1525 when the rebellious peasants approached the city (the peasants had already looted his ancestral castle in Thüngen ). The city of Würzburg joined the uprising on May 8th and 9th, 1525 respectively. On the part of the Würzburgers, the "Häcker" (wine-growing workers) and the "security guard " set up by Würzburg citizens took part: "... which initially prevented a lot of mischief, but then took part in the plunder itself." that the pauern ufruhr most parts of the uss the constant khome ... ”“ In Würzburg alone 63 castles were demolished. ”In addition, 31 monasteries in the Hochstift Würzburg were plundered, including, for example, the monasteries Oberzell and Unterzell as well as Himmelspforten . Today's estimates assume around 15,000 besiegers. The contemporary Würzburg city clerk Martin Cronthal estimated the number of attackers at 38,000. The attacking commanders included Florian Geyer and Götz von Berlichingen . Sebastian von Rotenhan , as the commander of the Marienberg, had 240 to 250 able-bodied men under his command to defend this last castle in the bishopric, which he divided into 18 squads. Each of these squads had to provide 4 men as tactical reserves.

The area to be defended was approx. 45 m × 100 m, with the long side very close to the east-west axis and the broad side on the north-south axis. The current designation " fortress " is not technically correct for the development of the facility at that time. At this point in time it was rather a " castle ". It was a concentric fortification system that lay on the ridge of a hill and had slopes sloping down on three sides and could only be reached more or less at ground level from the west. In the middle of the area was the still standing keep with a height of approx. 40 m, which was surrounded by a rectangular ring wall with the above dimensions, which was also the castle complex. This circular wall (= castle complex) was in turn surrounded by a wall with the original name "Wolfskeelscher Bering", later called Scherenbergring. (Each named after the prince-bishops Otto II. Von Wolfskeel 1333-1345 and Rudolf II. Von Scherenberg 1466-1495, who were responsible for buildings .) The Scherenbergring, with its round towers, was at the level of weapon technology and offered better resistance than outdated, angular ones against fire from heavy weapons towers also enabled the terrain in front of it by appropriate defenders, loopholes to spread, could without attacking troops in blind spots operate undisturbed.

The geographical weak point (to the west) was protected by the Scherenberg Gate, which still exists today, and a ditch in front of it .

The forward-looking (cartographer) Sebastian von Rotenhan had started preparing for the defense at an early stage. It is said that on April 20, 1525 the mayor and some councilors of the city of Würzburg presented themselves on the Marienberg to inquire about the reason for these measures. A visible element of this willingness to defend was above all the deforestation of the slopes and a pleasure garden in the northeastern area of the site that no longer exists today. A palisade wall was built from this wood outside the Scherenberg ring. In addition, additional loopholes were broken into walls and towers. Among the elements of this readiness to defend that are not visible from the outside are above all the ammunition of the castle with "fireworks" (pitch and sulfur) and the breaking of connecting corridors within the castle grounds, which later allowed the defenders to defend the defenders much faster in the event of an alarm To reach points of the castle or to strengthen them with additional forces. (Comparable to modern paratrooper tactics, for example during the siege of Bastogne in December 1944.) Sebastian von Rotenhan had alarm bells set in all directions for this purpose. Further measures were the conversion of the "Ratsstube" (to the north) and the "Haferboden" (to the east) into gun emplacements.

The actual siege began with troop movements on May 13, 1525: First, the fortress area was enclosed. In the north, coming from the Mainviertel from Zell, the Karlstadt farmers camped, who were later reinforced by the Odenwälder Haufen. In the west, in Höchberg, the Odenwälder ( Lichte ) Haufen had been encamped since May 7th . In the south of the Black Heap , Florian Geyer's troops, coming from Heidingsfeld and Eibelstadt. The Main runs in the east below the Marienberg, and parts of the city of Würzburg lie on the other side of the Main. The demand for the surrender of the fortress and other conditions (acceptance of the Twelve Articles of the Peasants; 100,000 guilders ; razing of the facility) were rejected.

On May 14, 1525, fire on the Marienberg Fortress was opened at 4 a.m. from Nikolausberg to the south. Additional (urban) guns were erected to the southeast near St. Burkhard below the fortress. However, the peasant artillery only managed to damage the outer palisade fence because the shooting distance (approx. 550 m) was too great for the field snakes used at the time . The potentially dangerous "Rothenburg Gun" was not brought by the farmers in time. The crew of the Marienberg Fortress did not allow themselves to be provoked and instead opened fire against the Main Bridge at around 6 a.m. in order to disrupt this connection line . Further targets of the fortress artillery were the German House (to the north) and the Judenplatz (to the east / today marketplace) in order to dissolve the crowds in these areas. The Main could only be crossed by the farmers and the townspeople using a wooden pontoon , which was erected below the Main Bridge in response to the bombardment.

The shelling caused considerable material damage in the city and became a psychological burden. On May 15th, the farmers decided on a nightly surprise attack on the important cannon position on the main side of the fortress in order to “ try to pull down the entrenchment against the place and the jacks behind it. “The picket fence fell, but the defenders held their own with firearms, pitch and brimstone, stones and boiling water. Most of the fighting probably took place in the northeastern part (" gein der Täle " = hollow path from the city beginning in the area of the Main Bridge up to the fortress) of the defense system. Martin Cronthal, however, also reports of dead in the (neck) ditch that was " severely chopped up and buried in it " facing west. Given the mass of attackers, it is obvious that there was fighting around the entire defense system. The noise of the fight could be heard as far as the city. There was a general mood among the citizens that one should not let the “ Christian brothers ” perish in such a “ way ”. However, no one dared to leave the city to assist the attackers, because the night " pitch black " and the " Geschies so great " was.

During a second storm, the farmers managed to take parts of the forecourt enclosure for a short time (today the Echterscher forecourt with horse troughs). However, they were quickly thrown back. However, this was by no means a militarily sensitive area that was not part of the core area, but merely an enclosure for a coal store and accommodation for 21 craftsmen and other workers. Even if the farmers had been able to hold their position, the neck ditch, the barrier wall and the curtain wall would still have to be overcome and that from a position that was permanently under fire and could only be reached via long and easily disruptive supply routes. A total of around 200 farmers were killed in these attacks.

After the failed storms, the farmers dug two entrenchments in the area of the “ Tael ”, but they could not develop any offensive potential and only insufficient protection against the gun emplacements laid out by Rotenhan in the east (“Haferboden”) and north (“Ratsstube”) of the Fortress grounds. The exact timing of the quickly abandoned attempt by some farmers in the St. Burkhard area to dig a tunnel in the Marienberg and to blow it up cannot be determined.

On May 18, 1525, the farmers tried again with additional guns from Nikolausberg to shoot the fortress ready for a storm. This time von Rotenhan returned fire and smeared the opposing positions with such intensity that their attendants had to take cover to such an extent that it was not possible for the farmers to continue the duel. The siege ended on May 23 with the withdrawal of the Neckartaler and Odenwälder heaps and the subsequent desertion of Götz von Berlichingen on May 28, 1525.

However, the actual escalation of violence did not begin until after the failed siege, when the relief army of the Swabian Confederation, led by Bauernjörg, arrived in the region. On June 2, 1525 there was a battle against approx. 7,000 farmers near Königshofen (approx. 30 km south-southwest of Würzburg), in which approx. 6,000 farmers were killed. The enormous failure rate of 85% on the part of the farmers resulted from a combination of weak leadership and the breaking of tactical discipline. Despite a favorable spatial starting position in the face of the enemy, the peasants moved haphazardly backwards and were massacred by the enemy cavalry . On June 4, 1525, the events of Königshofen near Giebelstadt (approx. 15 km south of Würzburg) were repeated . Here a peasant army of 4,000 to 5,000 men was wiped out.

Modern times

After a fire (triggered by Prince-Bishop Friedrich von Wirsberg ) on February 22, 1572, parts of the castle and the court library had been destroyed, from 1573 onwards, under the new Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, the center of prince-bishopric power in the Würzburg monastery was redesigned . operated as a renaissance castle , which has been preserved in its former form and which helped shape the silhouette of the city of Würzburg. Initially, repairs were carried out on the prince's building on the city side, and from 1575 the architect Georg Robin from Ypres advised the prince-bishop on the reconstruction of the west wing, the old armory and the inner castle. In 1579, Julius Echter had his new library, which later became famous, set up in the south wing.

The castle presented itself as a four-wing Renaissance palace complex with 17 gable gables (which disappeared again in the 19th century) after the north wing with the Marienkirche and the fountain house were restored after another fire from 1601 to 1607 according to plans by the Nuremberg architect Jakob Wolff .

During the Thirty Years' War , the Swedes under Gustav II Adolf conquered the fortress on October 18, 1631. The conversion to a baroque fortress was only carried out by the Frankish prince-bishops who returned after the Swedes were driven out.

Prince-Bishop Johann Philipp von Schönborn (1642–1673) and his successors had numerous other military fortifications and bastions built. A total of twelve kilometers of walls were built.

As a "new" access to the Prince Bishop's palace was 1652/1653 by Johann Philipp Preuss, the Neutor completed. The rich ornamental and figurative decoration of the sandstone fronts probably comes from Zacharias Juncker the Elder. J. , however, was largely renewed in the 20th century. The Neutor shows motifs relating to the ruler's government, such as allusions to the Peace of Westphalia that took place a few years earlier with Johann Philipp von Schönborn .

Next to the keep inside the castle is a well house, in which the 102 meter deep fortress well is located. It was excavated around 1200 and is fed by two springs and seepage water. The well is bricked to a depth of 75 meters and then carved into the rock. The shaft has an average diameter of two meters at the top and widens to four meters at the bottom. Up to 1600 the water was pumped with a winch and a pedal bike .

The prince's garden was first mentioned in 1523 and was essentially laid out by Johann Philipp von Schönborn (1605–1673). At that time it was still a medieval-style garden. From 1699 to 1719 it received its present form under Prince-Bishop Johann Philipp von Greiffenclau zu Vollraths . The figures were originally created by Jakob von der Auwera. Today there are replicas here.

Johann Philipp von Greiffenclau had already started further restoration work on the prince-bishop's palace at the beginning of his tenure in 1699. The Marienkirche, which served as the palace chapel, was refurbished . In the meantime, the ( acanthus ) stucco work of the rooms in the bishop’s apartment, which was in some cases overly ornate, was no longer in existence a decoration created by Pietro Magno have been preserved in the southern pavilion of the Fürstengarten). The gate of the Ravelins “Teutschland”, which was probably built in 1708 by Andreas Müller (1667–1720), is called “Äusses Höchberger Tor” and has cannon-shaped column shafts with relief depictions of Saints John and Philip, the namesake of the Prince-Bishop.

The Maschikuliturm was built from 1724.

Maria Renata Singer von Mossau was held as a prisoner at the Marienberg Fortress, she is considered the last Franconian victim of the witch burns.

In the Main Campaign in 1866, the Prussian army took the Marienberg, which served as a royal Bavarian fortress , under fire. The bombardment triggered a violent fire on the Marienberg, but the Bavarian fortress artillery was able to return fire effectively, and the Marienberg remained undefeated until the armistice, which was concluded on the same day as the first bombardment (July 26, 1866).

In 1871 the fortress housed over 5000 French prisoners of war . Also in 1917 there were around 80 French, Russian and English officers as prisoners there.

On April 30, 1933, a camp for voluntary labor service opened at Marienberg Fortress, which initially accepted 200 unemployed people placed by the employment office. The National Socialists used the castle as an " SA relief organization camp, whose important social and educational task is to retrain unemployed young SA comrades". The Marienberg court has become “a celebration of the community spirit”.

Under the Lord Mayor Theo Memmel , supported by the Bavarian Prime Minister Ludwig Siebert , extensive renovation measures were carried out on the Marienberg Fortress.

In 1938, the city history museum opened on the fortress and the Institute for Student History and University Studies , sponsored by the German Student Union and the Reichsstudentenführung .

During the bombing of Würzburg on March 16, 1945 , the fortress was badly damaged and was rebuilt from 1950 onwards.

architecture

- The towers

Outer courtyard

Around the outer courtyard there are other buildings, including the Andreas Müller designed until 1712 built 1,704 new armory on the esplanade in front of the Real Bastion. The castle is surrounded by several bastions and other gates, on its south side in the vineyards is the Maschikuliturm , a four-storey battery tower built by Balthasar Neumann in 1728 . A rare perspective of the fortress is shown in the picture View of the Marienberg Fortress by Erich Heckel , which is exhibited in the museum in the Kulturspeicher near the Würzburg pictures .

Inner courtyard

The mountain height was already around 1000 BC. Inhabited by the Celts in the 6th century, the Franks took possession of the hill. The first St. Mary's Church was built around 706 ; the Merovingian rotunda, which was later rebuilt several times, is one of the oldest buildings in Germany. The church is located in the inner courtyard, also the octagonal wells and the round in which in 1200 built the keep is. It was then that Bishop Konrad I of Querfurt began to fortify the castle.

The castle surrounding the castle courtyard is bordered on three sides by towers, the Randersackerer Turm (sun tower ) in the southeast, the Marienturm in the northeast and the Kiliansturm in the northwest. On the Marienturm there is the same image of Maria in a halo as on the tower of the Marienkapelle on the market (in line of sight). The inner courtyard is accessed through the Scherenberg gate. Around 1500, the "Bibra staircase" commissioned by Prince-Bishop Lorenz von Bibra was built as access to the bishop's apartment in the prince's building and in 1511 the new stair tower was completed. From 1572 onwards, Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn initiated major new buildings and renovations in the Renaissance style. Between the Scherenberg Gate and the Museum for Franconia is the outer portal of the Echter Bastion with the Echtertor, completed in 1606, above which a statue of the Archangel Michael, the “Imperial Patron and Guardian Angel of the Counter Reformation”, is attached.

Prince's garden

The Fürstengarten is a viewing platform with a garden at the eastern end of the fortress on a former gun platform. It was built from 1650 to 1700 in the style of the hidden Renaissance gardens of Italy ("giardini secreti") by Elector Johann Philipp von Schönborn . It can be reached from the innermost courtyard next to the fortress church. It is geometrically arranged with fountains, flower beds and pavilions.

Use today

Museums

The fortress now houses the Museum for Franconia with the Princely Building Museum . In addition, there are several restaurants (the castle restaurants ) with event rooms and some apartments that are rented out by the Bavarian Palace and Garden Administration.

Parking area

After the state horticultural show in 1990, the state horticultural show park was created within the extensive fortifications that extend as far as the Main. This also includes the garden by the Friedensbrücke, named after Philipp Franz von Siebold .

Monument protection

The building complex is a monument .

The description reads:

"Marienberg 239; Marienberg 240; Marienberg 241;

Marienberg Fortress

In front of the fortress: Maschikuliturm

Near fortress; Oberer Burgweg 2: Marienberg Fortress

- Celtic ring wall in the 1st millennium BC BC, Franconian-Thuringian ducal fort since the early 8th century, expansion into an episcopal castle since the beginning of the 13th century, reinforced in the 14th and 15th centuries. Under Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn (1573–1617) it was converted into an episcopal residential palace. Expansion into a fortress under Elector Johann Philipp von Schönborn and his successors through extensive bastion fortifications from 1650. Restoration 1936–1939. Reconstruction since 1945.

- Main castle: extensive square with corner towers, the wings in the core medieval, before and around 1600 by Georg Robin , Wolf Behringer and Jakob Wolff d. Ä. renewed;

- In the courtyard:

- Marienkirche, early Romanesque rotunda with rectangular choir around 1600; with equipment;

- Free-standing keep, 12th century;

- Fountain house, around 1600;

- The main castle is enclosed on three sides by a tower-reinforced, medieval ring, and in the west the Scherenberg gate;

- On the east side of the baroque prince's garden, around 1650.

- Outer bailey: three-wing complex with real bastion, around 1600;

- Portal by Michael Kern, 1605;

- Horse pond. Armory and commanders' building, a two-wing complex surrounding a second forecourt, 1709–1713 with the collaboration of Joseph Greissing (seat of the Mainfränkisches Museum).

- Fortifications in the Vauban system approx. 1650 - approx. 1730 by Michael Kaut, Johann Fernauer, Johann Philipp Preiß, Wilhelm Schneider, Giovanni Domenico Fontana, Andreas Müller, Maximilian von Welsch, Balthasar Neumann

- With the following bastions: Caesar, St. Johann Nepomuk, St. Johann Baptist, St. Nikolaus, Mars, Bellona, Werda, St. Sebastian, St. Michael,

- As well as the external works: Franconia, Reichsravelin , Teutschland, Teufelsschanze, Höllenschlund and the Maschikuliturm.

- Gates:

- Neutor, 1652/1653;

- Schönborntor, 1649;

- inner Höchberger Tor, 1684;

- outer Höchberger Tor, 1708;

- between the bastions vineyard walls, dry stone walls, 17th / 18th centuries century

Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation ( Monument List Bavaria 663000 , PDF) "

literature

- Daniel Burger : Fortresses in Bavaria. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7954-1844-1 , pp. 187-196.

- Georg Dehio , Tilmann Breuer: Handbook of German art monuments . Bavaria I: Franconia - The administrative districts of Upper Franconia, Middle Franconia and Lower Franconia. 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-422-03051-4 , pp. 1190–1196.

- Marianne Erben: Our Würzburg fortress. Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1998, ISBN 3-429-01988-5 .

- Helmut Flachenecker , Dirk Götschmann , Stefan Kummer (eds.): Castle - Castle - Fortress. The Marienberg in transition. (= Mainfränkische Studien, Volume 78). Echter Verlag, Würzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-429-03178-7 .

- Max Hermann von Freeden : Marienberg Fortress. (= Mainfränkische Heimatkunde. Volume 5). Stürtz, Würzburg 1982, ISBN 978-3-8003-0187-4 .

- Verena Friedrich: Castles and palaces in Franconia. 2nd Edition. Elmar Hahn Verlag, Veitshöchheim 2016, ISBN 978-3-928645-17-1 , pp. 140-149.

- Werner Helmberger: Marienberg Fortress Würzburg with the Princely Building Museum . Official leader of the Bavarian Administration of State Palaces, Gardens and Lakes. Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-941637-20-7 .

Web links

- Marienberg Fortress . In: Website of the Bavarian Palace Administration

- Marienberg Fortress . In: Website of the Museum für Franken

- Marienberg Fortress . In: Wuerzburg.de

- Marienberg Fortress . In: Burgenarchiv.de

- Marienberg Fortress . In: WürzburgWiki

- Entry on Marienberg Fortress in the private database "Alle Burgen".

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner Hess: Martin Luther. An introduction to his life. Evangelisches Verlagswerk, Stuttgart 1954, p. 55.

- ↑ List of persons according to Dr. Karl Heinrich Freiherr Roth von Schreckenstein : History of the former free imperial knighthood in Swabia, Franconia and on the Rhine, edited from sources . Second volume, Tübingen 1862, p. 265.

- ^ Carlheinz Gräter: The Peasants' War in Franconia . Stürtz Verlag, Würzburg 1975, p. 111.

- ^ W. Dettelbacher: Würzburg a walk through its past. Würzburg 1974, pp. 67/68.

- ^ Klaus Arnold: The peasant war. In: Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig (Hrsg.): Lower Franconian history. Würzburg 1995, p. 70.

- ^ A b Klaus Arnold: The Peasants' War. In: Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig. (Ed.): Lower Franconian history. Würzburg 1995, p. 73.

- ^ Rudolf Endres: The Peasants' War in Franconia. In: Peter Blickle (Ed.): The German Peasants' War of 1525. Darmstadt 1985, p. 172.

- ^ A b Andreas Lerch: The Peasants' War in Würzburg from a social historical perspective 1525. In: Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst. Volume 61, Volkach 2009, p. 84.

- ^ A b Max H. Von Freeden: Marienberg Fortress. Würzburg 1982, p. 53.

- ↑ a b Christian Leo: The Marienberg Fortress around 1525 - An attempt at a historical-topographical construction. In: Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst. Volume 61, 2009, p. 55.

- ^ W. Dettelbacher: Würzburg a walk through its past, Würzburg, 1974, p. 68.

- ^ Ulrich Wagner: The city of Würzburg in the peasant war. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. Volume III, Stuttgart 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ Christian Leo: The Marienberg Fortress around 1525 - attempt of a historical-topographical construction. In: Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst. Volume 61, 2009, p. 53.

- ↑ a b c Martin Cronthal: Attempt of the farmers to storm the Würzburgische Feste Unserfrauenberg. Report by the town clerk Martin Cronthal. In: Günther Franz (Ed.): Sources on the history of the peasant war. Darmstadt 1963, p. 359.

- ^ Klaus Arnold: The peasant war. In: Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig. (Ed.): Lower Franconian history. Würzburg 1995, p. 75.

- ↑ Max. H. Von Freeden: Marienberg Fortress. Würzburg 1982, p. 53.

- ↑ a b Christian Leo: The Marienberg Fortress around 1525 - An attempt at a historical-topographical construction. In: Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst. Volume 61, 2009, p. 54.

- ↑ Martin Cronthal: Attempt of the farmers to storm the Würzburgische Feste Unserfrauenberg. Report by the town clerk Martin Cronthal. In: Günther Franz (Ed.): Sources on the history of the peasant war. Darmstadt 1963, p. 358.

- ↑ Martin Cronthal: Attempt of the farmers to storm the Würzburgische Feste Unserfrauenberg. Report by the town clerk Martin Cronthal. In: Günther Franz (Ed.): Sources on the history of the peasant war. Darmstadt 1963, p. 57.

- ^ Andreas Lerch: The Peasants' War in Würzburg from a social-historical perspective 1525. In: Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst. Volume 61, Volkach 2009, p. 85.

- ↑ Max H. Von Freeden: Marienberg Fortress. Würzburg 1982, p. 54.

- ^ Klaus Arnold: The peasant war. In: Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig. (Ed.): Lower Franconian history. Würzburg 1995, p. 74.

- ^ Klaus Arnold: The peasant war. In: Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig (Hrsg.): Lower Franconian history. Würzburg 1995, p75.

- ^ A b Ulrich Wagner: The city of Würzburg in the peasant war. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. Volume III, Stuttgart 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer : Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 576–678 and 942–952, here: pp. 589–592.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer : Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 576–678 and 942–952, here: pp. 589 f.

- ↑ from Christophorus Marianus: Encaenia et tricennalia Juliana […]. Wuerzburg 1604.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer : Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 576–678 and 942–952, here: pp. 589 f.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer : Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 576–678 and 942–952, here: pp. 613 f.

- ↑ U. Steffens: Giovanni Pietro Magni .

- ↑ Winfried Romberg (Ed.): The Diocese of Würzburg 8: The Würzburg bishops from 1684–1746. De Gruyter, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-039295-1 , p. 252.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer: Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the rise of the Baroque. 2004, p. 628 f. and 633 f.

- ^ Sybille Grübel: Timeline of the history of the city from 1814-2006. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Volume 2, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 1225-1247; here: p. 1231.

- ^ Hans-Peter Baum : Fundamentals of the Würzburg Social History 1814-2004. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Volume 2, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , p. 1327, note 63

- ↑ Peter Weidisch: Würzburg in the "Third Reich". In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 196-289 and 1271-1290; here: p. 244 f.

- ↑ Die Woche magazine . Issue 21, May 20, 1936, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Peter Weidisch (2007), p. 249 f.

- ↑ Peter Weidisch (2007), pp. 256-258.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer: Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. 2004, p. 633 f.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer : Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 576–678 and 942–952, here: p. 578.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer: Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. 2004, p. 590 f.

- ^ City of Würzburg, Garden Department and Own Business Congress, Tourism, Economy (Ed.): Würzburger Gardens and Parks. Leaflet around 2003.

- ^ Burggaststätten Würzburg: Website .

- ↑ List of monuments Bavaria, file number D-6-63-000-317 ( List of monuments Bavaria: Würzburg , p. 50; PDF)

- ↑ D-6-63-000-317