Geology and landscape development in Brandenburg

The article describes the geology, landscape development and soils in Brandenburg and Berlin . The states of Brandenburg and Berlin (hereinafter referred to as Brandenburg) lie in the North German lowlands and were decisively shaped by the repeated advances of the Scandinavian inland ice during the Ice Age .

Solid rock deposits and deeper subsoil

As a specialty, there are geologically old solid rocks on the surface of the earth in six rather small-scale locations in Brandenburg, which protrude through the ceiling of the Tertiary and Ice Age deposits.

There are four deposits in southern Brandenburg. There you can find geologically very old rocks, quartzites and greywacke from the younger Precambrian . They mediate to the large solid rocks of Saxony further south. The two deposits on Koschenberg (near Großkoschen ) and near Großthiemig are also directly on the border with Saxony. The Rothsteiner Felsen in Rothstein is also known as an excursion destination . But just a few kilometers north of the Rothstein rock and the lesser-known quartzite occurrence of Fischwasser (Gem. Heideland ) are the so-called Central German Main Demolitions, locally known as the Lusatian Main Demolition. There, the old rocks quickly dive into great depths and therefore only play a subordinate role in the geological structure of Brandenburg.

Central and Northern Brandenburg therefore belong to the large North German-Polish Basin, which has been sinking more or less sharply since the Permian period and has been filled with deposits several kilometers thick. Sea deposits predominate, especially claystones , sandstones and limestones . They prove that in geological history Brandenburg was mostly a marine area and not a mainland.

The two hard rock deposits in Mittelbrandenburg, Sperenberg and Rüdersdorf owe their origin to the existence of a salt dome or a salt cushion in the subsurface. The upward migration of the zechsteinzeitlichen rock salt has in Sperenberg pierce all formerly overlying rocks, so that there gypsum is present as a solution of the residue salts. In Rüdersdorf, the rising salt lifted limestone from the Muschelkalk era to the surface.

All solid rock deposits were or are used as quarries for the extraction of building materials.

Deposits from the Lignite Age ( Tertiary )

Tertiary deposits are almost everywhere in Brandenburg, but mostly covered by the more recent ice age deposits. Their thickness varies greatly and is between a few meters and more than half a kilometer. The thickness of the tertiary deposits tends to increase from south to north, which well reflects the greater tectonic subsidence of Northern Brandenburg. During the Tertiary there were repeated sea advances from the northwest to beyond the southern border and vice versa to the retreat of the sea, so that there were also longer mainland times during this period.

In Brandenburg, the Oligocene and Miocene sections play a major role within the Tertiary . In the Oligocene (between 34 and 23 million years before today) almost all of Brandenburg was flooded by the sea, in which the so-called Rupel (or Septarian) clay was deposited. Wherever it can be found on the surface, it is extracted as a raw material for the construction industry. On the other hand, it is the most important underground reservoir in the country. It effectively prevents the rise of saline groundwater from greater depths.

In the following period of the Miocene (between 23 and 5 million years ago), the sea advanced several times and then retreated. Most of the sand was deposited in the mostly shallow water . But which are clearly known lignite , resulting in coastal bogs formed on the banks of the former sea. They are widespread throughout Brandenburg, but are only mined in southern Brandenburg. In central and northern Brandenburg, on the one hand, the cover of the overlying sediments is too large and, on the other hand, the thickness of the coal seams is less, since these regions were flooded more quickly when the sea advances.

Economically, lignite still plays a central role in Brandenburg today.

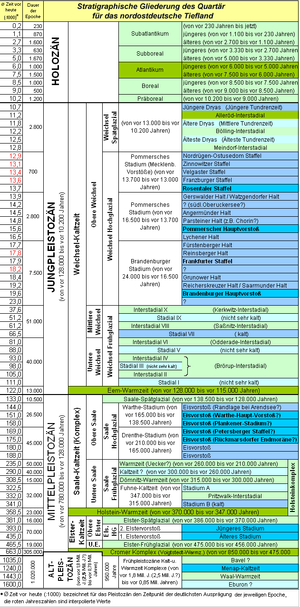

Elster ice age, Holstein warm time and early Saale ice age

Deposits from the Ice Age that are older than the Elster Ice Age have not yet been reliably detected in Brandenburg. The sediments of the first ice advances during the Elster Ice Age, which extended beyond the southern state borders, are, however, very widespread in the Brandenburg subsurface. They can be up to more than 100 m thick. They become particularly powerful when filling glacial channels . In Brandenburg, sediments from the Elster period consist mainly of marl boulder and sediments from ice reservoirs , which were deposited during two main advance phases. Meltwater sands and gravels are receding, especially in central and northern Brandenburg. Due to the overlay with the also very thick Saale-period sediments, Elster-period deposits are certainly only very sporadically directly on the earth's surface. The upper edge of the Elsterzeit deposits mostly shows no relation to today's surface.

During the warm Holstein period that followed the Elster Ice Age, large areas of lake deposits formed, especially in central and eastern Brandenburg . Very different types of sediments were sold. These include mudden , kieselguhr and clays with the characteristic snail species Paludina . These deposits can be found on the surface of the earth in the Fünfeichen Heights near Eisenhüttenstadt . At the height of the warm period there was a transgression (advance) of the sea from the North Sea basin into the Berlin area, so that marine-brackish deposits can be found up to that point.

Furthermore, the rivers coming from the south deposited significant amounts of sand and gravel during the warm Holstein period and especially in the long early phase of the Saale Ice Age , which today are of great importance as a groundwater reservoir and as a building material in southern and central Brandenburg . The Elbe flowed northwards from Torgau and crossed the Niedere Fläming, which did not exist at the time. The mostly sandy to gravelly deposits of this Berlin Elbe run are widespread in the underground of the Fläming and Teltow . The gravel of the Lusatian Neisse is just as widespread in southeastern Brandenburg, which is locally known as Tranitzer Fluviatil .

Saale ice age

The sediments deposited during the two Saale-age ice advances (Drenthe and Warthe) are thicker than both the Elster and Vistula ages. In many places they are significantly more than 100 m thick.

In the first advance phase, the Drenthe stage, Brandenburg was completely covered by the inland ice for the last time. The glacier reached its maximum extent on the northern edge of the low mountain range. In the advance phase, very thick meltwater sands were deposited and, during the ice cover, a relatively thick till , often more than 30 m thick. Deposits from ice reservoirs also occur in Lusatia in particular. South of the maximum extent of the younger Warthe advances are large areas of the Drenthe Age deposits on the surface of the earth. The meltwater sands in particular are often mined in gravel pits.

The younger Warthe advance only advanced as far as the Fläming and the Lausitz border wall ; nevertheless, this advance was very dynamic. The thickness of the wartime sediments, especially ice reservoir deposits and marl till, is very large in many places, on the other hand the inland ice has very strongly compressed the subsurface during this phase . In many places in Brandenburg, the significantly older tertiary deposits such as lignite or Rupelton were pressed to the surface (e.g. Rauensche Berge and near Bad Freienwalde (Oder) ). Furthermore, this advance noticeably revitalized the previously rather balanced relief. Many of today's high areas of Brandenburg, also in the northern part, which was later covered by the Vistula ice, were created at this time. The relief of the Fläming and the Lausitz border wall was decisively shaped. Several terminal moraine courses are still there. To the south, according to the glacial series, there are sand areas that flow into the Lusatian glacial valley , which was also created at this time. In the western Prignitz, on the other hand, which was also not reached by the Vistula, the situation is more complicated and has not yet been clearly clarified.

On the Fläming, the Lausitzer Grenzwall and in the Prignitz the deposits of the Warta advance are large areas. But also in the area later crossed by the Vistula ice, deposits from the time of the Saale are often found on the surface or in the immediate vicinity. The ice reservoir deposits in particular were or are being mined in numerous clay pits.

Eemwarmzeit and Weichsel ice age

In contrast to the deposits of the Holstein warm period, which occur over a large area in Brandenburg, those from the Eem warm period were deposited in numerous but rather small basins. They are spread all over the country; however, the focus is on southern Brandenburg, where the Eem deposits are mostly close to the surface. The interglacial deposits usually consist of various muds and peat deposits that have been deposited in lakes and swamps.

The long period of the early early glacial period in the Vistula, in which Brandenburg was not yet reached by the Scandinavian glaciers, is represented by periglacial sediments, i.e. sediments deposited under cold climatic conditions. Sands and silts predominate here . Above all, the Lusatian glacial valley was raised by several meters. On the other hand, there were erosion processes in the high altitudes. The young moraine landscape that existed after the Saale and Eem times was gradually transformed into an old moraine landscape. All the Eemzeit lakes silted up. Wind canters formed on the plateaus due to the sand carried by the wind .

It was not until the most recent high phase of the Vistula glaciation, less than 25,000 years ago, that Brandenburg was reached by the inland ice for the last time. About 20,000 years ago, the glacier reached its maximum extent at the Brandenburg ice edge and covered about two thirds of the country's area. The so-called Rixdorfer Horizont (after Rixdorf, today's Neukölln ) can be found at the base of the deposits from the Mollusc period, especially in Central Brandenburg . It is coarse-grained (gravel and pebbles), often contains the bones of large Ice Age mammals such as mammoth and woolly rhinoceros and is therefore of great value to fossil collectors. Above this mostly sands from the advancing phase of the ice follow, which are on average 10–20 m thick. The hanging glacial till is noticeably thin, especially in Central Brandenburg. It rarely reaches a thickness of more than 5 m; often it is even absent. Overall, therefore, the thickness of the Vistula period deposits remains significantly behind that of the older glaciation phases.

The ice advances from the Vistula Age are divided into two major phases, the Brandenburg and Pomeranian stages. While in the Brandenburg Stadium the ice advanced to the south - up to approx. 50 km south of Berlin - the maximum advance during the Pomeranian phase remained 60 km northeast of the city. Similar to the Saale Ice Age at the Warth stage, however, the Weichselian sediments of the Pomeranian stage are significantly thicker than those of the Brandenburg stage.

The line of the furthest penetration of the Weichselian glaciers is called the Brandenburger Eisrandlage . Locally, the ice pushed a little further south in an initial advance. Their expression varies greatly. Areas with very strong terminal moraines and large upstream sanders alternate with stretches where both terminal moraines and sanders may be missing. The Baruther glacial valley was formed at the time of the Brandenburg ice edge . The next terminal moraine to be followed over longer stretches, the Frankfurt Eisrandlage runs north of Berlin over the Lebus and Barnim regions . However, it is not without controversy in the specialist literature, as its course is strongly based on the older compression moraines that formed during the Saale period . Real terminal moraines were only formed to a subordinate extent during the Frankfurt ice rim location. The glacial till north of the ice edge corresponds to that of the Brandenburg advance. The associated sand pebbles are also rather thin and do not exist across the board. They form so-called tube sand, which has only partially buried or eroded the older ground moraine . The Berlin glacial valley was formed during the time of the Frankfurt ice rim . The numerous glacial valleys between the Baruther and Berlin glacial valleys were created when the two neighboring main valleys were not yet fully operational or out of operation. Typical of the Brandenburg Stadium are numerous glacial channels , which, as elongated hollow forms, often filled with lakes, noticeably enliven the landscape.

The Pomeranian ice rim (approx. 16,000 years ago) can be described as the best developed terminal moraine in northern Germany. He has received exemplary training from Chorin , for example . The terminal moraines are strong, often designed as a block packing. To the south there are extensive sands, z. B. the Schorfheide , which flow into the Eberswalder glacial valley . The ground moraine landscape north of the terminal moraine is also very well developed and sometimes extremely wavy. Regularly shaped drumlins can only be found very rarely. The marl boulder of the Pomeranian phase is up to 40 m thicker than that of the Brandenburg advance. Some smaller terminal moraine north of the Pomeranian main terminal moraine are present, albeit more indistinct. Their sands also drained to the Eberswalder glacial valley (nesting of the glacial series ). Brandenburg finally became ice-free around 14,000 years ago. Melt waters that still drained over the Brandenburg area formed the Randow valley , an glacial valley .

Ending Ice Age and Post Ice Age ( Holocene )

Immediately after the inland ice melted back, periglacial processes started under the still cold climate . The most important of these are the formation of permafrost and the blowing of sand by the wind. For example, while permafrost contributed significantly to the formation of the dry valleys that are widespread in Brandenburg today , the wind created inland dunes through the removal of wind edges and deflation troughs on the one hand, and the deposition of sand on the other .

At the end of the Ice Age, the permafrost subsided in the first warm phases, known as Bölling and Alleröd . As a result, the remaining blocks of dead ice finally melted and most of the Brandenburg lakes were created.

In the post-glacial period, deposition processes occurred, especially in the depressions and lowlands. Mudde in particular formed in the lakes , so that today a large part of the formerly existing lake basins has silted up again. On the old lakes, but also directly on the ice age deposits, peat increasingly grew up due to rising groundwater levels ; Moors formed. Today, Brandenburg is one of the federal states with the most bogs.

In the post-ice age, there were also major changes in the large river valleys of the Elbe and Oder . The Havel , the Spree and the other, rather small rivers only had a spatially limited reshaping and changing effect.

In the course of the post-ice age, humans also increasingly became a geological factor.

Floors

Due to the diversity of the Ice Age deposits in Brandenburg, the resulting soil associations are very heterogeneous. Their productivity ranges from extremely low in nutrients and sterile to very fertile.

The most productive and fertile soils can be found on the one hand on the Fläming in a sand loess belt between the cities of Bad Belzig and Dahme . On the other hand, there are very fertile soils similar to black earth in parts of the Uckermark in the north-east of the country. The soils there developed on silty glacial till or silty ice reservoir deposits . The other extensive ground moraine areas in Brandenburg, on which glacial till grows, are also comparatively fertile. Lessivés are most widespread in these locations , mostly in the form of pale earth . But parabrown earths and transition types to brown earth are also common. Waterlogging that led to the formation of pseudogleyen is present; due to the relatively dry climate, however, they are much less common in Brandenburg than in western Germany. The floodplains of the Elbe valley in the west and the Oder valley in the east of the country are also counted among the fertile soils of Brandenburg. They are most widely used in terms of area and at the same time most intensively used in the Oderbruch . The main types of soil there are Vegen .

The soils on the meltwater sand areas, which are also widespread and which have an extremely high quartz and feldspar content with simultaneous soil dryness, are significantly less productive . Minerals that can release or store nutrients when weathered are therefore hardly available. Brown soils , which show features of podsolization , were therefore preferred as soil . Real Podsols developed only to a minor extent due to the relative drought on these locations. These areas are currently mostly used for forestry and bear pine forests . Podsole and soils related to Podsol are often found on the extremely nutrient-poor dune areas that are very widespread in Brandenburg.

Due to the extensive lowlands, both gleye and bog soils are widespread in the state of Brandenburg . The gleye are found over a large area, especially within the glacial valleys, where the groundwater is a few decimeters below the surface. Transition types , especially to the brown soils and podsoles , are common. Due to the strong amelioration and the associated lowering of the groundwater, the occurrence of many gley soils must currently be viewed as a relic. In Brandenburg, moors can be found in large areas in the waterlogged glacial valleys. There it is mostly swamp bogs. However, the peat thickness is usually small. The bogs on the ground moraine areas and within the dead ice landscapes, on the other hand, usually have a smaller extent; however, they are very numerous and the thickness of the bog can be significant, especially in the case of silting bogs. The bog soils have also been intensively changed by man, so that the majority of the Brandenburg bogs have been drained and no longer actively grow.

In the settlements, especially in Berlin, anthropogenic (man-made) soils and urban soils are widespread. You can address them as young raw floors . Loose syrosemes and pararendzines predominate . Hortisols (garden floors), regosols and kolluvisols are also found here and there .

literature

- Gerd W. Lutze (author), Lars Albrecht, Joachim Kiesel, Martin Trippmacher (landscape visualization): Natural spaces and landscapes in Brandenburg and Berlin. Structure, genesis and use . Be.Bra Wissenschaft Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-95410-030-9 .

- Werner Stackebrandt, Volker Manhenke (Ed.): Atlas for the geology of Brandenburg . State Office for Geosciences and Raw Materials Brandenburg , Kleinmachnow 2002, 2nd edition, ISBN 3-9808157-0-6 .

- N. Hermsdorf, L. Lippstreu, A. Sonntag: Geological overview map of the state of Brandenburg 1: 300,000 - explanations . Land survey office Brandenburg, Potsdam 1997. ISBN 3-7490-4576-3 .

- Michael Succow, Leberecht Jeschke: Moors in the landscape . Urania Verlag Leipzig 1990, ISBN 3-332-00021-7 .