Rostock city fortifications

The Rostock city fortifications surrounded the city of Rostock since the middle of the 13th century. After the original city centers of the three Rostock sub-cities officially united into one city in 1265, the common, approximately three-kilometer-long city wall , which had more than 20 city gates , was built. These were divided into “land” and “beach gates”, depending on whether they led into the Mecklenburg hinterland or into the city harbor on the Unterwarnow .

At the time of the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), the complex was expanded into a fortress, especially under Wallenstein . When the city first grew beyond the boundaries of the city wall in the 19th century, this was de-fortified and in some cases greatly reduced in height. Parts of the city fortifications were destroyed as a result of the bombing in the Second World War or removed in the post-war period. Nevertheless, three of the massive brick country gates (stone gate, cow gate, Kröpeliner gate) and a beach gate from the classical period (monk gate), a wall tower (lagebush tower), large parts of the city wall over a total length of around 1300 meters and parts of the fortress wall are still today receive. In some passages the fortification was reconstructed in the 1930s.

History of the Rostock city fortifications

See also: History of Rostock

The fortification in the Middle Ages

The beginnings of the Rostock fortifications go back to the founding time of the city in the 12th century. At first it probably only enclosed the Petrikirche and the old market on a hill that rises about eight meters above the Warnow bank . A short time later, the Petritor was built below this hill and the "Flöhburg" was also built in between to provide further protection for the church and town. As was customary at that time, the fortifications consisted of a simple rampart , dry and water-bearing trenches and wooden palisades in the beginning . With the upswing of the brick kiln around 1200, the sensitive points of the fortifications could initially be strengthened by gates and wall parts made of field and bricks and thus responded to further developments in weapon technology.

In 1218, the first part of town around the Petrikirche was confirmed to have the town charter of Lübeck . Extensions to the south created a second center around the Nikolaikirche , which did not have its own town hall. The fact that in the south of this city center the later wall at the Grube (today Grubenstrasse ), which later encloses all sub-cities, showed a clear kink, suggests that this settlement also already had a fortification. The later swineherd's tower was also aligned with the course of this part of the wall, so a west gate is to be opened at the level of today's Viergelindenbrücke. West of the old town, two more fortified settlements were built, the middle town around the Marienkirche and the new town around the Jakobikirche , each with its own town hall. It is possible that the enclosures of the four settlement cores already formed a closed system.

After the three sub-cities merged in 1265, the city fortifications were systematically expanded. The city wall was about three kilometers long, enclosed an area of about one square kilometer and was up to 1.20 meters thick. It consisted for the most part of brick bricks , on a granite foundation of erratic blocks . The wall had a sloping brick roof and narrow, inwardly extended loopholes, as they were reconstructed on parts of the wall in the northeast. Semicircular Wiekhäuser , especially in the southwest, reinforced them at regular intervals, and later some of them were extended to form towers. Since 1400 the city wall had two ramparts and two ditches, from which the outer water led. If necessary, wooden battlements could be built at a height of about three meters below the top of the wall. Such battlements were restored in 1982/83 in the area of the Holy Cross Monastery and the Lagebuschturm.

The city gates were created in the 13th century as simple, largely unadorned building blocks with simple brick Gothic shapes, as the cow gate preserves to this day. There were no massive city portals like the Holsten Gate in Lübeck or the Crane Gate in Danzig in Rostock. As a means of architectural representation, Rostock's city gates were generally more reserved than those of smaller Hanseatic cities such as Salzwedel , Stendal , Demmin , Anklam or Tangermünde . The more important Hanseatic cities of Mecklenburg and Pomerania , Wismar , Stralsund and Greifswald , on the other hand, shared the relative simplicity of the city entrances. In the 14th and 15th centuries, however, six land gates and nine beach gates were expanded into gate towers. Since the end of the 14th century, Rostock has demonstrated its importance primarily through the height of the Kröpeliner Tor. In front of the stone gate there was the Zwinger, a round tower that was begun in 1526, as additional protection for one of the most important entrances to the city.

To protect the property outside the city wall, the natural watercourses, ditches, ramparts and thorn barriers served as a land defense . This Zingel were partially block or half-timbered houses additionally secured and gates. Defense jumps have also been found in Rostock since the end of the 15th century. These were each occupied by certain guilds, after which they were also given their names. The wall vppe deme Küterbroke was built in 1494, and the Wullenwewer Wall at the beginning of the 16th century. In 1559 the city council decided to fortify Rostock with rondelles and ramparts, each of which was given its own commander or captain.

Confrontations with the princes in the 16th century

See also: First Rostock inheritance contract

Ongoing conflicts with the sovereigns culminated in the fact that Johann Albrecht I marched into the city with 500 riders in 1565 while working on the rondelles and ramparts. In the following year he left the stone gate, its front gate, the Zwingerhof with its gate, the part of the city wall from the Wiekhaus at the Dominican monastery to the cow gate and the "tower on the Rammelsberg" with ramparts, ditches and bridges as well as parts of the east and south sides of the Grind the monastery. The city was thus open at an important point and thus severely weakened. With the help of 500 farmers from the region, he had his own sovereign fortress built in today's Rosengarten from the stones of the demolished buildings, which protruded into the city. Duke Johann Albrecht himself got off his horse on February 25th to throw the first spade of earth up to the hill. He intended to expand his fortress literally " as solid as goat grove ". The city guns were placed in the fortress and aimed at Rostock itself. The sovereign had free access to the Hanseatic city at any time and was able to control it better. Construction continued for the next few years. The Rostockers protected themselves against attacks during this time with chains, barriers and guards.

It was not until the First Rostock Inheritance Treaty of September 21, 1573 that the city was able to end the conflict, giving up important privileges to which the city owed its independence from the sovereign. She had to grant the royal house inheritance and high jurisdiction over the city.

After the citizens had to buy the right to do so from the duke, they razed his fortress the following spring and proceeded from 1574 to 1577 to the expensive reconstruction of the wall. Master builder Anton Bawald was commissioned to build ramparts and walls instead of the fortress. On May 10, 1574, the reconstruction of the wall from the Kuhtor began and work on the wall from the Zwinger towards the Mühlentor began. On June 17th, the foundation of the lagebush tower was laid on the site of the former prisoner tower on the Rammelsberg, and work on the stone gate began in the summer of 1574. It was only this new building that placed significantly more emphasis on architectural decoration in the contemporary Renaissance style than the earlier Gothic gate structures. The front was on the city side, while the field side was characterized by great simplicity. In 1576 the construction of the wall was continued up to the St. Johannis monastery. Even after that, work continued. Especially on the ramparts, which were very difficult and were interrupted in 1582 because the workers were needed elsewhere. In 1586/87 there were again complaints about this work.

Fortification in the Thirty Years War

Politically, the Hanseatic cities tried to strengthen themselves against the princes in the period before the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) by entering into closer alliances. In 1605, five cities, including Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen, formed a closer alliance. Other cities like Rostock followed later via the detour of the treaty with the Netherlands. In 1608 these towns hired a colonel general, Count Friedrich zu Solms , who was to keep an engineer for the fortresses. Since trade was already badly affected by the events leading up to the war, the cities looked for a power that would offer them the support they needed. Lübeck under the mayor Heinrich Brockes saw only the States General capable of this, as well as their governor Moritz von Orange . Only Lübeck took this step on May 17, 1613, but the other cities soon followed due to the continuing grievances. Rostock in June 1616.

Rostock had already made some necessary changes to the fortifications in advance. On March 7, 1608, the construction of the fishing bastion began, a roundabout on the blue tower. On April 29, 1611 a stone bridge at the Steintor, on March 15, 1613, it was decided to manufacture the new Zingel as a gate and to restore the drawbridge, on April 26, to continue with construction on the wall and to block it with wood that the water couldn't get through the bridge. In 1617, as the first action after the treaty, the outermost gate in front of the Kröpeliner Gate, which had previously been made of wood, was built with bricks. In 1618, the simple, wooden barrier in front of the stone gate was replaced by an outer gate.

The political alliance now required on the one hand the recruitment of additional armed forces, as well as the rapid reinforcement of the fortifications. These were not only out of date in Rostock, decayed and no longer able to cope with the technical developments in the gun sector. Solms was strongly committed to this work. The fortress construction engineer, who had received the appointment as engineer of the united Hanseatic cities on May 1st, 1609 , was that of Moritz von Orange himself, because with him the new methods of fortification had already proven themselves excellently in the fight against the Spaniards. This was Johan van Valckenburgh , who remained in the service of Prince Moritz. The assignment he received was: "To advise the cities of fortresses and buildings according to all his intelligence and ability, to correct the existing deficiencies and to correct them most detrimentally to the cities".

In 1613 the Rostock council wrote to Lübeck asking for a wall builder who knew how to build. He was informed of the approaching arrival of Captain Valckenburg in Lübeck. The council therefore decided on June 11th to invite him and received him on June 22nd, 1613. On July 9th he had obviously finished his work. The council reported that Valckenburg had drawn up two plans, including one that was more extensive. He also made a larger drawing with exact dimensions of two ravelins.

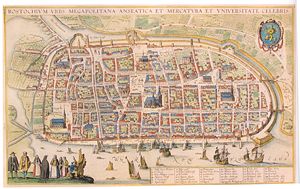

In 1620 the Dutch captain Kars joined the Rostock council in order to improve the condition of the fortification. Despite the constant improvements, he found this to be insufficient. It was only a matter of time before the war would reach Rostock as well. The wooden gate leaves were not adequately ironed and ironed, the gates themselves lacked stairs and floors for the guards, in the city center stables prevented the earthworks and galleries to get to the loopholes, ash and fruit trees also grew on the ramparts, and the city is as good as open at the cow gate, so Kars. In addition, he criticized the fact that no rows of stakes had been erected in the Unterwarnow and provided with a barrier to restrict the fairway and prevent enemy ships from entering. The citizens were then divided into quarters by him according to the parishes in order to take a position on the ramparts accordingly. In Kars' second report from 1623, he demanded that the council finally commissioned him to build more ramparts and walls; an engineer would also be needed to create a crescent moon (demi lune) in front of the Steintorzingel , where farmers fleeing to the city could protect themselves until they were helped. He also insisted on the entrenchment of Warnemünde. Ultimately, the captain was very dissatisfied with the situation that he hardly received any orders, and a short time later he joined Wallenstein's service. But even the council cannot have had a consistently positive relationship with Kars, since it asked Valckenburgh for advice again as early as 1620. But it was not until 1623 that he was able to make the first sketches of Rostock, and in 1624 after a visit, he made a first plan ( see illustration )

At the beginning of the 17th century, Rostock began to expand its fortifications according to his plans, but these could only be implemented in fragments. Valckenburg's plan only actually carried out the new work , which can still be viewed today , a three-wall bastion in front of the Kröpeliner Tor with an additional wall (fausse braye) at that time . The builder was a foreman Peter von Kampen, who had been recommended by Valckenburgh, who died in 1625.

The Hanseatic city took the side of the imperial at Hanseatic days early on. Nevertheless, work on the fortification was not continued in Rostock until 1628, when they came into the country themselves. Despite apologies from the Rostock Council to Arnim, Wallenstein demanded that the work be interrupted. It was clearly important to him to leave the fortifications in the damaged state, and he occupied the city on October 17, 1628 (whereby the captain Kars, who worked for Rostock, gave him the necessary information) in order to then undertake the improvements himself to care. In July 1628 a parapet was built on the Mühlenrondell, in September the gun was repaired and on September 21st, the jumps began to be raised in front of the Mönchen-, Lager- and Wokrentertor, then in October also in front of the Bramower Zingel. A hill in front of the Petritor, on which up to 300 workers from the nearby villages had to come to help, could not be completed, but the loopholes in the city wall at the Petrikirche. After a further inspection of the fortification on March 26, 1630 it was decided that the ravelins in front of the Kröpeliner and Steintor should be made by the imperial with the help of entrenchment graves from surrounding villages, while the Rostock citizens should build the entrenchments in front of the Schwaanschen and the Petritor . The imperial were preparing for a siege. The city's windmills were also torn down to build horse mills on the ramparts. The terrain in front of the ramparts was also shaved, barracks were built to accommodate soldiers on the ramparts and St. George was torn down from August 22nd to 25th, 1630. Rostock was then also enclosed by the Dukes of Mecklenburg together with the Swedes under General Tott in 1631 and after a 4½ month siege, the imperial Colonel Virmond surrendered the city to them on October 6th against the free withdrawal of his troops. The winners took care of the further changes to the fortification.

On October 8, 1631, Duke Johann Albrecht gave the order to destroy the works of the Swedish camp and the Landwehr as quickly as possible (which, however, had already begun), and to repair the ramparts and extra works. The Rostockers were also supposed to get rifles again, as they had been disarmed by the imperial when they withdrew.

On October 1, 1635, the city undertook to garrison 1,400 men and repair the fortifications. The work was specified in a council memorial on January 28, 1636: the tower guards were to watch day and night, the corps de guarde in front of the Rotten Gate was repaired, the bridge demolished on the new plant, the holes in the parapets filled, below Palisades should be set at the plant and the fisherman's roundabout repaired as soon as possible and the barrier on the Unterwarnow closed to prevent enemy ships from entering the port.

The fortification until the 18th century

The actual destruction in the 17th century had less military causes than natural ones. During a storm surge in 1625, the entire city wall from the Heringstor to the Gerbhof was torn down, and another one severely damaged the fishing rondel in 1663. Especially during the great city fire of 1677, the wall suffered from the heat. The economic decline of Rostock after the end of the Hanseatic League and the devastation caused by the city fire contributed to the increasing decline of the city fortifications. Some of the destroyed areas could only be poorly repaired with palisades.

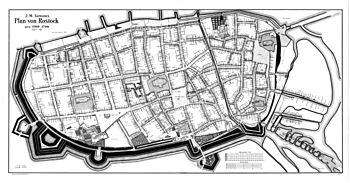

The threats posed by the Northern War , however, made it necessary to rebuild the facilities, which are now also obsolete from a military point of view. Immediately after taking office in 1713, Duke Karl Leopold set about securing Rostock according to the latest findings in fortress construction . Plans were drawn up in the same year (see Fig .: Knesebeck , Sturm ). After fierce resistance from the Rostock citizens who had to do trenching work or payments and whose gardens, houses and land adjacent to the wall would have been damaged by the work, from 1717 they were content with repairing the city fortifications. After the execution of the Reich against the Duke in 1719 and the withdrawal of the Mecklenburg and Russian troops from the city, plans for a simplified expansion did not seem to have been carried out.

Demolition and reconstructions

In the middle of the 18th century the city fortifications lost their military function and fell into complete disrepair. The city council perceived the costly maintenance of the facilities as a burden, the wall and the gates as an obstacle to the development of traffic. From 1832 a systematic softening began, beginning with the Mühlentor, after individual towers had been torn down and jumps leveled as early as 1720. Most of the wall to the city harbor was removed, and most of the beach gates were torn down. In other sections, the height of the wall was reduced. Wallstraße was built between Steintor and Schwaanscher Straße , and in 1857 the rose garden. From the middle of the 19th century, the city grew beyond the boundaries of the city wall for the first time.

In 1936/37 the section between Steintor and Grubenstrasse was restored. The cow gate, which had been plastered up until then and served as a simple residential building, was restored to its original form. During the Second World War , large parts of the historic city fortifications were badly damaged by the bombing of Rostock on the night of April 23-24, 1942. While the Kröpeliner Tor was hardly damaged, the Stein, Kuh and Petritor burned out completely and were only stumps of the wall. In 1948 the western city wall between Kröpeliner Tor and the Fishermen's Bastion was torn down to make room for a parade ground that was never realized. The stone gate received a copy of its curved tower helmet in 1953; the ruins of the Petritores, however, were demolished in May 1960, as they allegedly represented an obstacle to motor traffic and trams. In 1982/83 the city fortifications were restored. Since the 1990s, walls at the stone gate and at the Petrikirche have been brought up to the streets. At the stone gate, twelve steles that glow green at night serve as a visual merging of the wall and gate.

Land gates

In the west, south and east up to nine gates led into the Mecklenburg hinterland of Rostock. As land gates, these were distinguished from the so-called beach gates , which led to the city harbor on the Unterwarnow in the north . In terms of defense, the land gates were more important for Rostock and were therefore more strongly fortified. All land gates were probably preceded by front gates and drawbridges about 20 meters away. The gates are listed in their order from west to east.

Bramower Gate

The Bramower Tor (Bramowsches Thor) was the westernmost city gate of Rostock. It got its name from the former village of Bramow in the Rostock city field, which is now part of the city. It was also known as the Green Gate because of its slate roof .

The gate, first mentioned in 1265, led from Langen Straße to Warnemünde . According to the representation on the Vicke Schorler roll, it was nevertheless given a multi-storey structure. There was a front gate beyond the moat.

In 1722 the Bramower Tor was demolished. Today only the street name at the Green Gate reminds of this part of the Rostock city fortifications.

Kröpeliner Tor

The Kröpeliner Tor (Crepelin's Thor) was first mentioned around 1260. Whether it was named after the small Mecklenburg town of Kröpelin or after a patrician family of the same name is a matter of dispute. It represents the western end of Kröpeliner Straße and led to the important trade route to Wismar and Lübeck .

In the course of time, the gate was expanded considerably and raised by five floors in 1400 to 54 meters today, making it the most representative of the Rostock city gates. The original two storeys can still be recognized by the different colors of the stones. In addition, traces of the extension and the city wall as well as a wooden battlement that was previously attached below the top of the tower are visible.

In 1847 a neo-Gothic porch was added to the gate tower . During restoration work in 1905, a griffin was inserted into the large pointed arch panel on the field side. In 1945 the porch was removed for aesthetic reasons, although it was undamaged during the war. In addition, a piece of the city wall to the north of the Kröpeliner Tor up to the fishermen's bastion was demolished in favor of unrealized traffic plans. There are plans to close the gap between the gate and the city wall again, but these were initially rejected in April 2006.

A tram line ran through the gate and Kröpeliner Strasse until 1960; later it was moved to Lange Strasse . During restoration work from 1966 to 1969, the gate to the Museum of City History was rebuilt, but it was closed in 2004. Since then it has been the seat of the Rostock History Workshop.

Schwaansches Gate

The Schwaansche Tor stood at the end of Schwaanschen Strasse and was built in the 13th century as a sideline gate . It was a slender gate tower with a tent roof and tall Gothic window facing the city. The gate and street take their name from the small Mecklenburg town of Schwaan of the same name . Its function quickly transferred to the nearby stone gate, so that the Schwaan Gate lost its importance and was closed in the course of the fortification of the city during the Thirty Years' War. In the 1830s it was demolished in favor of the building of the Great City School that still exists today .

Stone gate

The stone gate (Porta lapidea) was built in its present form between 1574 and 1577 in the Renaissance style. The original gate, built in 1279, soon replaced the Kuhtor, a little further to the east (at that time the Old Stone Gate ) as the city's main portal to the south. Its size probably resembled the early Kröpeliner Tor , which was built at the same time. From the stone gate, the paved stone road led directly to the Neuer Markt, the political and economic center of the city. The stone gate stood in its original form for almost 300 years until it was razed by Johann Albrecht I in 1565 .

In the depiction of the gate on the Vicke-Schorler roll , it can be seen that its roof was still covered with shingles instead of slate towards the end of the 16th century . The shrine at that time to the gateway passage went over the entire width of the building. In contrast to today, Schorler's depiction also includes cartouches next to the coat of arms-bearing lions. In the left is the beginning of a chorale by Joachim Magdeburg from 1572: Whoever God trawt has probably bawt . In the right one says: By being stylish and hoping you will be sterile (according to Isaiah 30:15). The inscription under the coats of arms also differs from today's, although the meanings do not differ significantly. Both relate directly to the conflict with the duke that led to the demolition of the old gate. At Schorler it is called: Dominus confortet seras portarum et benedicat / filiis tuis. Intra te concordia, publica felicitas perpetua (May the Lord strengthen the bars of your gates and bless your children in you. May there be unity and public welfare in you). The first part is the transformation of a statement into a request from Psalm 147:13 of the Bible, which says: Quoniam confortavit seras portarum tuarum; benedixit filiis tuis in te. (According to Luther : Because he ( Yahweh ) tightens the bars of your (Jerusalem) gates, and blesses your children in your midst.) In the line below in Schorler's description: Common peace a beautiful stand, through this one preserves city and country. One can assume that this part was added by Schorler. In today's version, the inscription on the gate simply reads: Sit intra te concordia et publica felicitas (Within your walls, unity and general welfare prevail).

The field side deliberately only bears the city and state coat of arms in a small rectangle. The stones for the portcullis and the loopholes can still be seen today. The simplicity on the side facing away from the city symbolizes resistance and demonstrated strength. On the other hand, wealth was represented on the city side. Two lions there bear three historical coats of arms: that of the prince with the griffin, the large city seal with the bull's head and the Hanseatic city arms, the three-colored shield with the griffin.

On the field side of the gate stood the Zwinger, a squat round tower with six meter thick walls, which was removed in 1849 as a traffic obstacle. In addition, the gate had a direct connection to the city wall for a long time, which was removed in favor of the course of the street. It was not until the destruction caused by the Allied bombardment in 1942 that an extensive restoration of the building became necessary, which was carried out by the builder Grützmacher in 1950–1954. In 2005, the missing connection to the city wall was symbolically restored by twelve steles that glow green at night , as well as a five-meter extension of the still existing city wall on the east side.

Cow gate

The cow gate was first mentioned as such in 1325, but dates from the second half of the 13th century. It was described as the Old Stone Gate in 1260 . This makes it not only the oldest of the still existing gates, but also one of the oldest buildings in Rostock and the oldest preserved city gate in Northern Germany. It led to the road to Bützow and Werle . As the city's most important exit gate to the south, however, it was soon replaced by the (new) stone gate . The only thing left to do was to lead the cattle through to the Warnow meadows , which gave it its later name, Kuhtor . The four-storey defense tower is 8 by 9 meters wide and has a wall thickness of 2 meters. The gate is 3.5 meters wide and 3 meters high.

At the end of the 14th century, the field side was walled up and when it was used as a light prison (custody) from 1608, so was the city side. It was later made usable as an apartment. The town's gunsmith lived in the Kuhtor since 1671. Since 1825 it had been completely converted into a residential building, which was available as an apartment for city officials, craftsmen and day laborers until 1937. In 1938 it was partially reconstructed and on the field side the passage arch with the early Gothic pointed arch, the blinds and the German ribbon were restored. Four years later, bombs hit the gate badly. 1962–1964 the building received a roof again, but it was not fully reconstructed until 1984 and from 1985–90 it was the seat of the district executive of the GDR Writers' Association . Until 1993 the gate belonged to the cultural office, from 1998 to 2000 it was again fundamentally restored and handed over to a literary support group as an independent sponsor when it reopened. Since then it has housed the Rostock Literature House, which regularly hosts readings and events, as well as the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania Literature Council.

Mill gate

The mill gate (Mollenthor, Porta molitera) stood at the southern end of the street Am Bagehl . The gate led to Mühlendamm , one of the two historical crossings over the Oberwarnow , which led to the arterial road to the southeast. The name of the gate referred to the water mills, of which there were many in the once widely branched network of the Oberwarnow southwest of the city walls, of which the street names Mühlenstraße and Mühlendamm bear witness. In the course of the fortification of Rostock during the Thirty Years' War, the Mühlentor ravelin was built in front of the originally Gothic gate . At the beginning of the 19th century, the original building had to give way to a simple wing gate, which in turn was demolished in the course of the city's demolition from around 1840.

Gerbertor

The Gerbertor got its name from Gerberstrasse, which ran east of the city wall through the Gerberbruch to the Warnow. The gate is first mentioned in 1306 and is still mentioned in 1730. In 1368 it was referred to as Loertthor (i.e. Lohetor ).

Kütertor

The Kütertor (Kiterbrock), first mentioned in 1305 , was named after the Küterbruch, where the Küter (butcher) grazed the cattle.

Petritor

The Petritor (St. Petersthor, Porta Sancti Petri) was one of the four main gates of the city. It was very likely built towards the end of the 13th century. In its appearance and size, it resembled the cow gate.

The Petritor was in the east, at the foot of the steep hill on which the first Rostock settlement around the Petrikirche was founded. From the Petritor you got to the trade route towards Stralsund via Petridamm . During a renovation in 1720 it was given a pyramid roof and in 1935/36 the plaster that was subsequently applied was removed during extensive repairs. Until the beginning of the 20th century, the Petri Bridge in front of the gate led over the old Warnowarm, a small tributary of the Warnow. However, this was filled in in order to be able to implement structural measures in road construction in this area.

The gate was badly burned out during the bombardment of World War II on the night of April 23-24, 1942, but it was not completely destroyed with the surrounding walls preserved. The demolition of the Petritores on May 27, 1960 began overnight to prevent protests. It was blown up and the debris was removed within a day. The reason given was that the Petritor represented a dangerous traffic obstacle at the exit of Slüterstrasse , as motorized traffic and trams crossed there.

If the reconstruction should still have been provided for in the urban development master plan from 1998, nothing in this direction took place for a long time. However, some efforts are being made today to enable the gate to be rebuilt. Among other things, the Rostock History Association is involved. In 2006, as part of the renovation of the north-eastern city wall, a 14-meter-long section of the wall was added to Slüterstrasse, although this differs in the color of the stones. The official reason for this is that the subsequent addition should be made visible. With the renovation of this historic gate area, discussions about the construction of a new gate began again. An exact reconstruction of the historic gate does not seem to be an option at the moment, since access to the city is to be guaranteed at this point, especially for the fire brigade.

Beach gates

The gates to the city harbor were called "beach gates" or "water gates" and thus distinguished from the "land gates". The importance of the port and the orientation of the Hanseatic city towards maritime trade is evident from the fact that the number of beach gates exceeded that of land gates. Originally, all beach gates were simple gates, which were later expanded, especially in the central part. According to Wenzel Hollar's view of the city from 1657, nine of the beach gates were house gates with stepped gables facing both the city and the harbor, the other four (pit gate, wine gate, Kößfelder gate and Badstuber gate) wall gates (wickets) without gatehouse. Originally, Wiekhäuser were built into the city wall on the beach side as well, but they were later considered superfluous and removed. The beach gates derived their names from the streets leading towards them. In front of seven of them was a landing bridge of the same name : Mönchen-, Koßfelder-, Burgwall-, Lager-, Wokrenter-, Schnickmanns- and Fischerbrücke. At times there were more than seven bridges, one or two bridges (W. Hollar) were in front of the pit or Hering gate at the mouth of the pit.

For the city and the state government, the beach gates only lost their importance in the 1860s, when the " gate toll " was imposed there . With the exception of the monk's gate, all beach gates had been demolished by 1896. The gates are listed in their order from west to east.

Fisherman's gate

The Gothic Fischertor (Vischerthor, Porta piscaria) was the westernmost of the beach gates. It stood at the northern end of Fischerstrasse and was first mentioned in 1319. The Fischertor was demolished in 1870. As usual at the beach gates in Rostock, it had a simple, defensive appearance. In front of the fisherman's gate there was a cordoned-off port basin that was reserved for river fishermen as a landing stage.

Grapengießertor

The Grapengießertor , which delimited Grapengießerstrasse in the north, was first mentioned between 1335 and 1395 and was later expanded into a house gate.

Badstübertor

The Badstübertor (Badtstüberthor) was at the northern end of the street of the same name . It is first mentioned in 1326. The Badstübertor received no structural upgrade to a house gate, but only had the character of a gate. Nor did it have a jetty.

Schnickmannstor

The Schnickmannsttor delimited Schnickmannstrasse in the north. Via it and the Breite Straße to the south , you got directly to the Hopfenmarkt , today's Universitätsplatz . The namesake of the street and gate was the Rostock patrician family Schnickmann. The Kaufmannsbrücke in front of the gate formed the westernmost point of the city harbor . The gate was first mentioned in 1310.

The Schnickmannstor was demolished in the course of the city's fortification after the Wars of Liberation .

Wokrentertor

The Wokrentertor (Wuckrenterthor) stood at the northern end of Wokrenterstraße , named after the merchant family of the same name and the 30 km southwest of the village of the same name, now part of Jürgenshagen . It was first mentioned in 1310.

Camp gate

At the northern end of the camp street was the camp gate , which was first mentioned in 1327. After it burned down in 1608, the camp gate was rebuilt in its unchanged form. In 1870 it was "sold for demolition" and demolished that same year.

Burgwalltor

The castle wall gate (Borchwalthor) is documented in 1334 at the earliest. The merchant's bridge in front of the gate formed the center of the harbor. In the early modern period until 1887 there was a wooden stepping crane (originally a stone crane ) for loading the goods and, since 1865, a customs house. In 1868 the gate was sold for demolition and put down in the same year. A reconstruction of the earlier wooden harbor crane has been standing approx. 200 m west of the former Wokrenter Tor for several years .

Koßfeldertor

The Koßfeldertor (Kufellthor), first mentioned in 1316 , stood at the northern end of Koßfelderstraße, from which you can directly reach the New Market via the now no longer existing alley at the Marienkirche , once the main trading place of the city. The gate and the street take their name from a merchant family that came from the Westphalian town of Coesfeld . The Koßfeldertor was demolished in the course of the town's fortification in the middle of the 19th century.

Wine Gate

There was also a small beach gate , the wine gate, at the northern end of the wine route . Until the 17th century it was also called Faules Tor, as in the work of Wenzel Hollar from 1625 and Caspar Merian from 1653, as the later Wine Route was previously called the Faule Grube . It is not to be confused with the Faulen Tor (formerly Altes Tor ) located three gates to the east . This wine gate was a simple wall gate without a gate, less important than its neighbors and was built over with a house around 1789. Johan van Valckenburgh did not mention it on his 1624 plan. Both lazy gates are named as such on the Vicke-Schorler scroll .

Monk gate

The Mönchentor (Münchethor) is Rostock's last surviving beach gate. It forms the beach-side end of the Große Mönchenstraße in the northern old town. It was first mentioned in 1316.

The originally Gothic gate was renovated in the 16th century in the Renaissance style. An early depiction is on the Vicke-Schorler scroll from 1586. In 1805/1806 a new gate was built according to the plans of the university professor Schadeloock in its current, classicistic form on the foundation of the old one. It got pilasters , a graded Attica and crowning an Empire vase.

The beach bailiff's apartment was on the upper floor of the gate . In front of the gate stretched "the beach", the port area of Rostock since the Middle Ages. The promenade along the Unterwarnow is still called Am Strande today . Ferdinand von Müller , who is considered the most important botanist in Australia, was born in the beach bailiff's apartment in 1825 .

In contrast to the completely destroyed Große Mönchenstraße, the gate was not hit by bombs during World War II and was renovated in 1990/92. Today the Kunstverein zu Rostock uses the building, which was founded on December 30, 1992 and which received the gate from the city on February 1, 1994.

Pit gate

The mine gate was at the northern end of the mine road , which ran parallel to a former branch of the Unterwarnow, the mine. The side arm left the city for the harbor through a water gate in the wall. The pit gate was located on the border between the old and middle town and was first mentioned as such in 1385. As early as 1364, however, it appeared in the city books as the Hering Gate . The name can also be found on the works of Hollar and Merian. Because of the nearby hospital (plague house) it was also called Lazareththor in the 17th century . It retained its original character as a gate and was not expanded into a house gate.

Rotten gate

The Faule Tor was at the northern end of today's Faulen Straße, which was formerly called Alte Straße. It was first mentioned in 1532, but has been documented under its older name Altes Tor since 1290. The gate was flanked by a small tower.

Turning gate

The turning gate , the easternmost beach gate, was first mentioned in 1352. It connected the Wendenstrasse with the beach. Access to the beach was through a small tower.

Wiekhäuser and towers

Between the land gates, at a distance of 50 to 80 meters, were cradle houses of the older, semicircular and open to the rear type with three loopholes each set into the wall. Their diameter was around nine meters, the wall thickness up to 2.20 meters.

In the late Middle Ages, Wiekhäuser were converted into towers at strategically important points. This particularly affected the wall sections in the western end of the city port and in the south between Stein- and Kuhtor.

Towers in the northwest of the city wall

The slender Kaiserturm made of half-timbered buildings was built between the Grapengießer and Fischertor . To the west of it, a Wiekhaus was extended to form the high, five-story Blue Tower, which got its name from the slate roof color, which is unusual for northern Germany. This was followed by the Bußebahrt tower ( Bußebart tower , Dusbar at Hans Weigel's) and the gun foundry tower, both with half-timbered structures.

Kennel

The construction of the Zwinger began in 1526 and continued from 1528 to 1532 under the direction of the Wittstocker Hans Percham. Although the tower already existed at the time of Vicke Schorler , he did not include it in his image of the city.

The large building with a wall thickness of about six meters and a diameter of 20 to 24 meters was located south of the stone gate, i.e. outside the wall ring. In it were cannons to protect the most important gate of the city and the wall section. The way into the stone gate made a bend around the kennel and formed a forecourt between them.

As a traffic obstacle, the city had it demolished in 1849 with the help of Prussian pioneers .

Lagebuschtower

The Lagebuschturm , formerly known as the Fangelturm or Eissturm , is the only remaining tower in Rostock's city fortifications. The Gothic predecessor building erected in 1456, the prisoner tower on the Rammelsberg, was part of the fortification section that was demolished on the orders of Johann Albrecht I. The current building was built in the Dutch Renaissance style until 1577 . In addition to its function as a defense tower, it also served as a prison until the 19th century.

Water art

The water art was a high wall tower between the Kuhtor and the Mühlentor, which lay directly above the southern entrance of the pit into the city area. Water was pumped into the Altstätter Born via a wind engine on the top of the tower. According to the images that have been preserved, the Gothic architecture of the water art on the city side seems to have been sophisticated.

In 1662, the water art was handed over to the university , which set up an observatory there called a specula and tore down the wind engine. In the 1830s, the water art was demolished.

More towers between the stone gate and the cow gate

To the west of the stone gate, the powder tower was built from a Wiekhaus, a multi-storey tower with a conical roof. The cow or swineherd tower stood immediately to the east of the waterworks.

literature

- Friedrich Bachmann: A plan of the siege of Rostock from 1631 and the fortification of the city since about 1613. In: Contributions to the history of the city of Rostock. Volume 18, (1931/32), pp. 7-78. Published by the Rostock Antiquities Association. Carl Hinstorff , Rostock 1933.

- Georg Dehio: Handbook of the German art monuments. Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Revised by Hans-Christian Feldmann, p. 466 ff. Munich, Berlin, Deutscher Kunstverlag 2000, ISBN 3-422-03081-6 .

- Ludwig Krause: To the Rostock topography. With two plans. In: Contributions to the history of the city of Rostock. Volume 13 1924, pp. 12-64. Published by the Rostock Antiquities Association. Carl Hinstorff : Rostock 1925.

- Adolf Friedrich Lorenz : On the history of the Rostock city fortifications. In: Contributions to the history of the city of Rostock. Volume 20, 1935, pp. 27-78. New university publications publisher, Rostock. ISSN 1615-0988 (PDF file; 2.19 MB)

- Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch : The old Rostock and its streets. Redieck & Schade publishing house , Rostock 2006, ISBN 3-934116-57-4 .

- Wilhelm Rogge: Wallenstein and the city of Rostock: A contribution to the special history of the 30 Years War . In: Yearbooks of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology. Schwerin i. M. 1886, p. 283 ff.

- Heinrich Trost (Ed.), Gerd Baier et al. (Ed.): The architectural and art monuments in the Mecklenburg coastal region. Henschel, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-362-00523-3 , pp. 338ff.

- Horst Witt (ed.): The real "Abcontrafactur" of the sea and Hanseatic city of Rostock by the shopkeeper Vicke Schorler. Rostock 1989, ISBN 3-356-00175-2 .

Web links

- Contribution to Fortifica - German fortress research

- Joachim Lehmann: The kennel in front of the Rostock stone gate.

- Hans-Otto Möller: The Petritor - A monument that has disappeared

- All around instead of in the middle: a tour around the city wall

- Boulders landed in bed - The Petritor Rostock through the ages

- alt-rostock.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gerd Baier: The cityscape as a mirror of history. In: Monuments in Mecklenburg. Weimar 1977, p. 106.

- ↑ See: AF Lorenz: On the history of the Rostock city fortifications. In: Contributions to the history of the city of Rostock. Volume 20. Rostock 1935, p. 30.

- ↑ Gerd Baier: The cityscape as a mirror of history. In: Monuments in Mecklenburg. Weimar 1977, p. 106.

- ^ Rogge: Wallenstein and the city of Rostock. 1886, p. 342.

- ↑ See: Bachmann: A plan of the siege of Rostock. P. 10 ff.

- ↑ See: Rogge: Wallenstein and the city of Rostock. 1886, p. 344.

- ↑ See: Bachmann: A plan of the siege of Rostock. P. 12.

- ↑ See: Rogge: Wallenstein and the city of Rostock. 1886, p. 347 f.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 71.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 85.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 122.

- ↑ Cow Gate. In: 3dwarehouse.sketchup.com. August 30, 2019, accessed on August 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 89.

- ↑ Petritor Rostock at mv-terra-incognita.de

- ↑ Rostock can hope for his Petritor. In: Ostseezeitung . July 24, 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Gerd Baier: The cityscape as a mirror of history. In: Monuments in Mecklenburg. Weimar 1977, p. 106f.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 92.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 80.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 55.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 26.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 24.

- ↑ Ralf Mulsow, Ernst Münch: The old Rostock and its streets. 2006, p. 148.

- ^ Adolf Friedrich Lorenz: On the history of the Rostock city fortifications. 1935, p. 48.

- ^ Adolf Friedrich Lorenz: On the history of the Rostock city fortifications. 1935, p. 77.

- ↑ Friedrich Bachmann mentions the essay in his text A plan of the siege of Rostock from 1631 and the fortification of the city since around 1613. In the contributions to the history of the city of Rostock, Volume 18 (1931/32), p. 7. He criticizes that Rogge used few of the sources available to him because important information was lost and his picture of the development was thereby falsified.