Roman villa of Königshof-Ödes monastery

The Roman villa of Königshof-Ödes Kloster , one of the Roman villas in Pannonia , has long since disappeared from the earth. The area has been on Kaisersteinbrucher soil in Burgenland since 1921 . After the amalgamation of the municipalities, it is part of the larger municipality of Bruckneudorf . Excavation is prohibited on the military training area, but this area was also the target of many amateur archaeologists.

Groller's excavations from 1903

In the vicinity of the chapel ruin on the Klosterwiese west of Kaisersteinbruch (Hungarian: Császárkőbánya ) in western Hungary who led archaeologist and Colonel Maximillian Groller of Mildensee 1903 on behalf of the Academy of Sciences excavations . The excavation of the Roman camp of Carnuntum near Deutsch-Altenburg on the Danube was also carried out under his direction . As a result, he found that three independent settlements arose on this conveniently located site in Roman times .

Early villa

The early villa consisted of structures A, B, N and P, probably also of other buildings, most of which were destroyed during the expansion of the moat and wall system and the building walls were demolished. B was a residential building that had one larger and several smaller rooms. The smaller rooms were heatable. A was connected to B by a wall. On the designated area north came with the inscription IVLIOR the only stamp brick the excavation revealed. There found coins of the emperor Domitian and Nerva help with the timing of the buildings. At point P there was the corner of a building from this early period made of roughly chiseled ashlar stones, and the door frames and thresholds are also made of well-worked limestone . The remains of the buildings of this early villa, dating from the beginning of the 1st to the 2nd century, are likely to have been torn down and leveled after a fire or destruction, as they probably consisted of earth walls and trenches built at the beginning of the 3rd century Fortifications stood in the way.

Attachment

Following the decay of the buildings from the earliest period, a fortification with a moat and earth wall was built from a later period. The only building that belongs to the fortification is the tower marked O, which is wedged into the corner formed by the ditch system. The foundation on which a tower was built in wooden structure, forming a row of bricks. The fortified settlement was not built until the 3rd century and offered its residents protection and security until around the beginning of the 4th century.

Later fortified villa

The 80–120 cm thick border wall, which forms an irregular polygon - outside of which the wall system on the western and southern sides has been preserved intact - provided the buildings with protection. During the uncovering, the strong surrounding walls could still be ascertained 1 m high in most places. Under the masonry, the durability of the wall ensured a foundation, the depth of which varied between 20 and 40 cm and was provided with a 15-30 cm protruding base.

A tower foundation was excavated on the east side, 7.40 × 5.90 m in size, the threshold stone was still in situ in its west wall . The tower walls were 60 cm thick. The foundations of an intermediate tower were visible on the east wall. The thickness of the wall of the 6.10 × 5.20 m tower is 90 cm, so it is stronger than that of the gate tower. The buildings within the stone wall are of the same age and were built at the same time as the stone wall. According to the general chronology of the Pannonian villas of a similar type ( Donnerskirchen , Purbach etc.), the time of origin of this fortified villa is in the 4th century.

A northern group of buildings (CDR and Q) and a southern group of buildings (EFGHIK) can be identified on the area combined to form a unit by the wall. In the area of the villa there is no building that can be described as a “luxury home”. The villa from the Öden Kloster does not look like the center of a large latifundium and property of a rich landlord , it gives the impression of a settlement of several families consisting of several houses, living quarters and workshops . The settlers reinforced the protective devices and the wall system with a wall and so it was here that they imagined

Late Roman industrial center

and probably also a center of agriculture in the area. The developed buildings are also workshops or warehouses , but almost each had one or two heatable rooms that served as apartments.

Building C consists of seven small rooms. Two entrances led from the east into room no. 1, the actual courtyard. Room no. 7 is likely to have been the living room of building C, which is otherwise used for industrial purposes. In courtyard no. 1, an almost intact door on a cellar descent led to the basement , in which a stove that had remained completely intact was installed. Before it was a pottery kiln , after the renovation it served as an oven . Groller added that a similarly intact furnace in the Limes region has not yet been developed. The building consists of the staircase, the vestibule and the actual oven. The steps were made of quarry stone and are each 50 cm high and 60 cm wide. The descent is 180 cm long and has a gradient of 25 cm on this section to the anteroom.

In building D lay the destroyed remains of a similar oven as in C, room 5. Next to the oven, on the floor in a large heap of fine sand and pebbly, well- grouted clay. Here, too, the bottom of the furnace was made of red-baked clay .

Southern villa wing

Courtyard No. 1 forms the center of the south wing, around which buildings G, H, I and K were built. The greatest interest is due to building K on the south front of courtyard No. 1, where living and utility rooms were available. The ventilation openings observed in building K deserve special attention because they have not yet been found in Pannonia, rather the tower-like dry storage facilities were common.

Epitaphs

sarcophagus

The internal structure of building F is not known, only the rectangular outline. When the wall VI met building F, stone slabs of a sawn-up sarcophagus decorated with figures emerged from the wall (Figure 92). The grave had been built secondarily from used, relief stones. The figures were chiseled off the stone slabs so that only the contours are visible. On the larger stone slab there were three figures carved in a recessed niche , and a half-figure on the smaller one. A standing figure was once immortalized on one of the sawn, narrow panels and a round altar table on the other.

The walled area marked F can be designated as a burial place . The floor of the grave, which was composed of slabs, was laid out with broken bricks, the former stone grave box was probably in situ in this way .

The building E shows a two rows of pillars structured , three-aisle configuration. An entrance threshold appeared in situ on the west side, near which three rooms were housed. The middle part was an approximately 10 m wide, uncovered courtyard, on the two side rows of pillars, which were not parallel everywhere , the half-roof covered with shingles rested. In one of the closed rooms, the floor was laid with 20 × 10 × 5 cm, so unusually large bricks. This is likely to be the remains of the later, medieval floor level.

Barb ties the emergence of all the buildings outside the wall to the rule of Charlemagne . Others believe that the foundations of Building E are Roman. In the era of Charlemagne, only the new use of the building fell. The Roman origin of the buildings with a similar floor plan, such as Building E, which also occurs as an annex to the Roman villas in the empire, in Britain , Germania and Pannonia, is undoubtedly clear.

Old Christian basilica

Knowing the Pannonian material, it can be established that it is this type of building from which the early Christian basilicas belonging to the Roman villa settlements or villas emerge. At the end of the day, one can remember that Königshofer Building E served ritual purposes in a section of its existence as a basilica .

Water pipe

In the area of the northeast corner of the rampart system, a spring is shown on the plan . Even if several springs provided water at that time, the aqueduct , whose interlocking, burnt clay pipes were found in all buildings except E, Q and R by the excavators, started from here.

Roman - medieval finds

Both materials were present in all buildings, even in buildings A and D, which could no longer be used at a later date. First of all, the window panes that form the integral part of the building should be mentioned, four panes in C, one fragment each in B and K.

The area is quite poor in terms of stone monuments. A fragment of an inscription from Building A, in the form of several altar fragments I (ovi) o (ptimo) m (aximo). The two stones adorned with reliefs were not found during the excavations, but they come from this area. On the one drawing is almost only in outlines a woman in typical local costumes shown on the shoulders with one primer Norican -pannonischen type. There may be traces of an Attis figure on the other side of the stone .

The stone with the native female figure belongs to the earliest period of the Roman villa von Königshof. It comes from the grave field of the villa residents from the 1st – 2nd centuries. Century. The modest interior of the buildings and the found material show that the character of the villa was a rural, production- oriented villa rustica .

Inhabited since ancient times

The fragments of prehistoric vessels, stone and bone tools that have come to the surface at the highest point of the area testify that the place, which is particularly suitable for settlement, was already inhabited in prehistoric times .

Groller also published a drawing and a picture of a ceramic group, the pieces of which are stamped on the edge. It turned out that these were so-called " Viennese pots ", which were very popular in the 15th century, especially in the area around Vienna. This last-mentioned type of ceramic, which continued into the 16th century, indicates the time until the royal court was last inhabited.

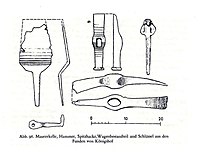

Finds from the royal court

The objects shown are kept as Roman finds. The trowel was found in building A, the mason's hammer in building I. The pickaxe came to the surface from the northeast corner ditch. The car leaning nail was in the section of road that had been exposed in the middle of the settlement. The L-shaped iron key, the most common in Roman times, with a handle with a round hole, speaks for the Roman origin of the building.

The group of knives and tools with maker's mark, as well as arrowheads and lances are highlighted. The determination of the temporal affiliation of the royal court, knives and iron implements provided with maker's marks is made more difficult by the fact that they also appeared in the area of the Carnuntum camp and their depiction always takes place in the company of Roman iron objects. From the part of Pannonia, which lies on the territory of Hungary , iron tools with master's marks from Roman layers have not yet been observed. The signs bear more of the character of the Middle Ages than that of Roman times.

The main misunderstandings are that Groller, when he carried out the excavations in 1903 on the Limes and in the villas, did not consider that the originally Roman camps could possibly have been inhabited later, during the early and later Middle Ages .

The location of the knife with the maker's mark and handle decorated in bronze is building B. The blade with a gear-like stamp was found in building A. The pointed blades , marked by the lilies placed on the base , came out of building C. The maker's mark in the form of small crucible tongs on a soft-hardened iron knife from building I. A small blade was also found in building K, bearing a six-pointed star as a symbol. The maker's mark of the sickle unearthed from building E is a round stamp divided into four fields. The iron implements with the maker's mark probably belong to the period of the villa in which vessels with an edge stamp were used.

Finally, the small finds from the Villa von Königshof also include several arrowheads, of which similar specimens were often found in the Limes camps, but they do not date from Roman times. In Hungary, mostly in the 13th to 14th Century similar in use.

Coin finds

The following coins were recorded from the area of the Königshofer Villa: large bronze from Emperor Domitian (81–96) and Nerva (96–98) at the southeast corner of building N, large bronze from Antoninus Pius (138–161) on the brick flooring of building E, Small bronze from Claudius II. (268–270) from the outermost wall, small bronze from Konstantin jun. (337-340) from building K, two Constans coins (337-350) were on the east wall of building Q and two coins from Emperor Valentinian II (375-392) in the middle of the fortified area, near the with S on the exposed road section.

It has not been recorded whether other coins than Roman coins appeared in this area. If there had been such a thing, Groller's accuracy would certainly have mentioned them.

Summary by Edit B. Thomas

The archaeologist Edit B. Thomas (1923–1988) summarized the site as follows:

As some prehistoric finds show, the hill above the Leitha river was already inhabited in prehistoric times as a favorable settlement area .

The area, which is not far from the important trade and military routes, attracted settlers as early as the 1st century, who also found forests, fields and the necessary water nearby. Here, in buildings A, B, N and P, a real villa rustica was built, which - although not furnished with excessive luxury - with its heatable rooms still guaranteed its residents a pleasant stay. The buildings of the villa rustica, which belonged to the first period, probably burned down and perished in the turbulent years at the end of the 2nd century, but there was no new construction.

In the first decades of the 3rd century, a small fortification surrounded by a system of ramparts and ditches was built at this key point , where the important road leads over the Leithagebirge nearby , presumably to secure the road and the Bäckerkreuz Pass Built of wood and their planks were pelted with clay. The stone buildings C and D within the wall with their heatable rooms and terrazzo floors were built later. In this way, the fortified Königshofer settlement can also have served as a permanent station and mansion.

At the beginning of the 4th century, buildings E, F, G, H, I, K etc. were built and the building complex was surrounded with a solid wall, creating a fortified villa, a refuge that the workshops, the The associated fields, forests and, in all likelihood, the livestock was suitable for self-sufficiency , self-sufficiency .

The possibility is pointed out here that an early Christian community may have existed within the walls , whose members used building E together with the Christian residents of the area as a basilica for cultic purposes, which the floor plan makes very likely.

Since Groller only announced groups that were torn from the material, we do not know who lived in this fortified, relatively protected settlement from the 5th to the 7th centuries, nor do we know anything about life in it. Here, too, as in other Pannonian settlements ( Keszthely-Fenékpuszta , Sümeg , Baláca, Gyulafirátót-Pogánytelek, etc.) we have to reckon with the one to two hundred year survival of the late Roman culture and way of life, which the culture of the time of the migration here in gives several waves of incoming peoples a new color, a new coat of paint.

Alphons Barb said: ... our fort is a "royal court" in the clear sense of the word, one of those fortifications systematically built by Charlemagne based on the Roman model. They are fortifications that look completely Roman and were therefore long considered Roman. In his study, Barb was able to give a high probability of the assumption that the area in question was a fortress in the Carolingian era .

There is only one thing we (Edith B. Thomas) cannot agree with for the reasons already given, namely that he only recognizes the first and no other period from Roman times. These controversial issues could be put into perspective through some exploratory excavations .

It was therefore one of the southernmost stations of the fortress system developed against the Avar Empire , which also served as a protection and base for the troops at the time of the Magyar incursions .

King Imre I of Hungary donated the area of Königshof to the Cistercians from Heiligenkreuz in 1203 . During this time, most of the reconstruction of the Roman buildings, the new buildings, including the construction of the chapel indicated on the plan as a ruin , took place. The only thing that can be determined from the ruins is that the chapel, which is oriented exactly to OW, was a Gothic building. The lay brothers probably lived a monastery life on the monastery property.

The settlement described above, founded by the Romans and inhabited for almost one and a half millennia, was destroyed according to P. Adalbert Winkler during the Turkish invasion in 1529.

The state of research in Austrian art topography 2012

- The thesis of the planned relocation of the Heiligenkreuz Abbey in the years 1206 to 1209 was not adopted by later research.

- Three layers of settlement can be identified (in extracts):

- Some authors ( Edit B. Thomas , Wilfried Hicke) confirmed the remains of a Roman castrum with an early Christian , apsidless hall church from the 4th century .

- An earth fort from the Carolingian era was found . The dimensions, the wall and moat profile and the arrangement of the corner towers correspond to the so-called royal courts that Charlemagne built as a base on the borders of his empire.

- The Cistercians built a grangie , an approximately square area (150 × 150 m) surrounded by a stone wall. Inside numerous medieval buildings, a large oven or kiln , as well as parts of a three-aisled hall building (44 × 22 m). Today only remains of the foundation walls are preserved.

Roman coins found in 1933

When clearing a tree trunk in 1933, a pot with Roman coins came to light in the coins of the emperors Lucius Verus (161–169), Mark Aurel (161–180), Cornelia Salonina wife of the Roman emperor Gallienus, Galerius (305–311) , Licinius I (308–327), Constantinus I (324–337), Fausta , wife of Constantinus, mother of several future emperors and Constans. It is a depot whose hiding time was at the end of the reign of Constantine I.

From the description it can also be seen that the most recent coins can be dated to the year 370. As Vergrabungszeit or -basic turmoil are on Donaulimes specified. It seems possible that minor attacks by the barbarians on the other side of the Danube, who were able to advance into this apparently rich area on the northern slopes of the Leithagebirge without difficulty, were the reason for hiding the treasure found . The owner will have been a local farmer or trader who made this considerable cash - as far as the find report.

See also

The Kaisersteinbrucher quarries

In the middle of the 16th century some Magistri Comacini settled there , traditional names are the master stonemasons and sculptors Antonius Gardesoni , Alexius Payos , Pietro Solari etc. and worked in the surrounding quarries , the desert monastery quarry, forest quarry, Kaiser quarry. Here the starting point of the independent Kaisersteinbruch craft was the master mason and mason .

literature

- Edit B. Thomas : Roman villas in Pannonia, contributions to the Pannonian settlement history , Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 1964

- P. Adalbert E. Winkler: The Cistercians at the Neusiedlersee and the history of this lake . St. Gabriel printing works, Mödling near Vienna, 1923; New edition 1993.

- Burgenland State Archives : Topography of Burgenland, Neusiedl am See administrative district , 1955.

- Helmuth Furch : A desolate monastery, scanty remains! In: Mitteilungen des Museums- und Kulturverein Kaisersteinbruch , No. 35, 1994. ISBN 978-3-9504555-3-3 .

- Helmuth Furch: Historisches Lexikon Kaisersteinbruch , 2 volumes, 2004. ISBN 978-3-9504555-8-8 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Edit B. Thomas : Roman villas in Pannonia, royal court "Ödes Kloster" . Pp. 152–174, extracts from it

- ↑ Alphons Barb: A castle of Charlemagne in the Leithagebirge . In: Kleine Volks-Zeitung, Sunday supplement on August 22, 1937. Barb was director of the Burgenland State Museum at the time, and in later years worked at the University of London.

- ^ Austrian art topography , volume LIX, The art monuments of the political district of Neusiedl am See . Published by the Federal Monuments Office, editorial management Andreas Lehne . Verlag Berger , Horn, 2012, pp. 120–150. ISBN 978-3-85028-554-4 .

- ^ Helmuth Furch, Mitteilungen des Museums- und Kulturverein Kaisersteinbruch 1994, No. 35, pp. 18 ff.

- ↑ Robert Wögerer: Wilfleinsdorf, history of the place and the church , the Roman times . 1996, p. 3.

Coordinates: 47 ° 59 ′ 43.3 " N , 16 ° 44 ′ 1.8" E