Somali Bantu

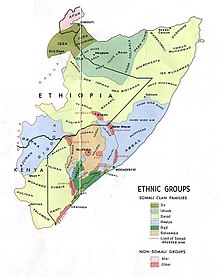

The Somali Bantu , also Jarir , Jareer , (Wa) Gosha or Muschunguli , are ethnic minorities compared to the vast majority of Somali in East African Somalia . In a narrower sense, the descendants of members of various Bantu ethnic groups are included, who were sold to Somalia in the 19th century as part of the East African slave trade from today's Tanzania , Malawi , Mozambique and Kenya . Most of them settled in the Jubba valley in the south of the country after their escape or their release . In a broader sense, other groups in southern Somalia are also included who are said to be descended from Bantu, who lived there before the slave trade.

There is different information about their population, because on the one hand population figures for Somalia are generally uncertain and on the other hand the term Somali Bantu is interpreted differently. Estimates range from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands.

Because of their descent from slaves, their sedentary peasant way of life and their external characteristics, which differ from the majority of the population, the Bantu are discriminated against by parts of Somali society . In the civil war in Somalia since 1991, they were disproportionately affected by acts of violence, looting and the resulting famine . Some of them have therefore fled to neighboring Kenya, of which over 12,000 have been resettled as refugees in the USA since 2003 .

Terms and designations

" Bantu " is a term used in linguistics and includes over 400 ethnic groups with around 200 million people in Central, East and South Africa who speak the Bantu languages .

The Somali Bantu do not represent a homogeneous ethnic group and traditionally see themselves more as members of the individual village communities or extended families in which they live, their respective Bantu peoples and / or the Somali clans to which they have partly joined, than as a uniform ethnic group . Older descriptions in which they are described as “a tribe of escaped slaves” do not correspond to reality in this respect. Only recently has an awareness of a common history and identity and the self-designation Bantu developed among those Somali Bantu who fled to Kenyan refugee camps before the civil war in Somalia . Before that, most of the people were unfamiliar with the term “Bantu”.

The collective name Bantu for those minorities in Somalia was used for the first time by some European anthropologists and colonial officials in the colonial times, alongside local terms ( Gosha or Italian Goscia , Muschunguli ) and foreign names such as negri (" negro ") or liberti ("freedmen" or " former slaves ”). In recent times, Somali Bantu (English Somali Bantu ) has been widely used in the language of Western media, international organizations, etc. since the early 1990s. In scientific publications more differentiated terms are still used, as they were traditionally used in Somalia by the "Bantu" and Somali.

- Mostly the term Somali Bantu refers to the descendants of Bantu slaves from Tanzania, Mozambique, Malawi and Kenya, who were sold to southern Somalia and who after their escape or release mainly settled in the valley of the Jubba River . This article mainly covers the past and present of this group.

- Sometimes other minority groups are included in the designation. They are considered to be the descendants of a population that lived in the valleys of Jubba and Shabeelle and between the rivers before the slave trade began, before they were ousted to small areas by the Cushite-speaking Somali and Oromo . It is unclear whether they were originally Bantu (see also Shungwaya ). These groups include the Gabaweyn in the upper Jubba Valley, the Shidle and Makanne in the Shabeelle Valley near Jawhar and Beledweyne and the Reer Shabelle and Rer Bare in Ethiopia. The majority of them practice arable farming and are " clients " with neighboring Somali clans. In English-language publications they are therefore also summarized as client-cultivator groups . In the course of time, former slaves also joined them.

Some of them reject the term "Bantu" because they would never have spoken a Bantu language, and they are reluctant to adopt an identity linked to the ancestry of slaves, while claiming to have lived in Somalia before. - Several Somali clans between the rivers and in the Shabeelle Valley each include a subgroup of "Bantu" - often both descendants of slaves and others - who were adopted as part of the clan through formal adoption ( sheegad ). They are integrated into the clans to varying degrees and apart from this clan membership do not have an independent group identity.

(Wa) Gosha or Reer Gosha refers to the Bantu in the lower and middle Jubba Valley (north of Kismaayo between Jamaame and Bu'aale ), who descended from former slaves. The Somali word gosha is a geographical name for that section of the Jubba Valley that was densely forested and largely uninhabited until the arrival of the Bantu, as disease-transmitting tsetse flies and malaria made it unattractive for the Somali herders. The prefix Wa- stands for “several persons” in various Bantu languages, reer is a Somali word for “people from”, “descendants of”. Wagosha / Reer Gosha can thus be translated as “people from the forest”, with a specific reference to that forest area. Reer Goleed has the same meaning but can refer to any forest.

Those among the Wagosha , who trace their ancestry back to the Zigua or Zigula people in Tanzania and who have maintained strong cultural ties to this former homeland to this day, also call themselves Zigula . The Shanbara also identify themselves based on their Bantu people of origin, but now speak exclusively Somali. The Zigula also call all those Gosha residents who no longer speak Bantu languages Mahaway , which is a corruption of their pronunciation of Somali. The Somali name Muschunguli probably comes from the singular name of the Zigula, Muzigula . Strictly speaking, it only refers to the Zigula, but was and is also used for all Gosha residents. In Somalia it is used in a derogatory way.

The groups named - slave descendants and other groups of unknown origin in southern Somalia - have in common that they are viewed as different by the Somali majority based on physical characteristics and given the name Jarir (pronounced "Jarir", mostly written Jareer in English-language publications ). It is a Somali word for "hard-haired" or "curly-haired", which in contrast to Jileec or Jileyc ([ dʒile: ʕ ]) - "soft-haired" - (or bilis , "master" as the opposite of "slave") ) is used for non-Bantu or Somali and, in addition to curled hair, implies other characteristics such as slightly darker skin color, certain ("softer") facial features and body shape.

Adoon and Habash are derogatory terms that are translated as “servant” or “slave”. Some Somali also call the Bantu after the Italian word for "today" Ooji , which comes from the assumption that the Bantu cannot think beyond today.

- To be distinguished from the groups mentioned so far - and mostly not regarded as "Somali Bantu" - are members of the Swahili society . This speaks the Bantu language Swahili , is based on the East African coast from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique and took part in the slave trade itself. In Somalia, this group includes the Bajuni in Kismaayo and the residents of the city of Baraawe .

history

Slave Trade and Slavery in Southern Somalia

In the 19th century, various interrelated developments caused the East African slave trade to peak and the import of Bantu slaves into what is now Somalia increased significantly: trade in the Indian Ocean - in which the towns on the Benadir coast in southern Somalia took part - grew , Zanzibar rose to become an important trading center, and the slave plantation economy emerged in the East African coastal region. This was also related to the fact that the demand for slaves in America , which had an impact on slave prices across Africa, gradually declined since the late 18th century; the consequent falling prices enabled buyers within Africa and the Arab-Islamic world to buy more slaves. Daus , who transported slaves from East Africa to Arabia, often made a stop on the Benadir coast, where provisions were obtained and some of the slaves had already been sold. Especially in the Shabeelle Valley in the hinterland of the Benadir Coast, plantations were established that produced surpluses of grain, cotton and vegetable dyes for export. Various Somali clans who owned land in the Shabeelle Valley were involved. The labor requirements of these plantations were met with imported slaves, especially since most Somali traditionally live as nomadic cattle breeders and do not value the work in agriculture.

Between 1800 and 1890 an estimated 25,000 to 50,000 black African slaves were sold to the Somali coast via the slave markets of Zanzibar , Bagamoyo and Kilwa Kivinje . (In total, over a million slaves were traded in the Arab slave trade in East Africa in the 19th century.) In 1911, the Italian colonial administration estimated the number of slaves in southern Somalia at 25,000–30,000, with a total population of 300,000. They came mainly from the Bantu ethnic groups of the Yao , Makua , Nyanja ( Chewa ) / Nyasa and Ngindo from northern Mozambique, southern Tanzania and Malawi and the Zigula (Zigua) and Zaramo in northeastern Tanzania. Other groups came from the Nyika ( Mijikenda ) and other ethnic groups from Kenya , other groups are occasionally mentioned.

Most of these slaves were sold to the Benadir coast ( Baraawe , Merka , Mogadishu ) and from there further inland, mainly to the plantation-used areas in the coastal valley of the Shabeelle . On a smaller scale, slaves also reached the Bay region further inland, where they were used in small-scale farming by the Rahanweyn (Digil-Mirifle). Several thousand slaves remained in the coastal cities, where they were owned by Arab and Somali traders in the textile industry (as weavers), in the operation of sesame oil mills , as house servants, porters and dock workers. Nomadic Somali also pursued slavery, although their economic importance was less for them, and the main source of procurement for slaves were raids and wars against the neighboring Oromo (who are not part of the Bantu but, like the Somali, belong to the Cushitic-speaking peoples).

Settlement in the Jubba Valley

For runaway slaves and freedmen who did not want to remain dependent on their masters, there were essentially opportunities to join Islamic brotherhoods ( tariqa ), move into existing villages of free Jarir farmers, or found their own villages.

From the 1840s - perhaps even earlier - slaves who had escaped from the Shabeelle valley settled in the Gosha area in the Jubba valley, where they founded villages and farmed. This area, located in the current administrative regions of Lower and Central Jubba , is characterized by dense forest cover and the presence of seasonal water reservoirs (dhasheegs) . It had remained uninhabited until now, apart from the Kushite-speaking hunters and gatherers of the Boni and Somali nomads who crossed it seasonally.

The Zigula from northeastern Tanzania were among the earliest of the new settlers . Oral tradition has it that they were caught during a famine by slave traders who promised them food and work. (These traditions are associated with famines in the area of the Zigula around 1836, but also between 1884 and 1890. In the case of several other famines in the region in the course of the 19th century, those affected, knowingly or unknowingly, went into slavery.) After their arrival In Somalia they lived as plantation slaves for a few years and then tried to get to their area of origin in a joint, organized escape south. When they reached the Gosha area, however, they settled there because the further way would have been too long and dangerous. Since most of the Zigula fell into slavery as adults and remained in it for a few years, they retained strong collective memories and cultural ties of their former homeland, including the Zigula language . The other early settlers were also linked to their Bantu origins, albeit less strongly, and mostly those who traced back to the same people of origin moved to the same village. In addition to the languages of their respective home nations they used Swahili as a lingua franca . In 1865, Karl Klaus von dercken estimated the number of inhabitants in Gosha at 4,000.

Another settlement of former slaves arose in Haaway in a swampy area on the lower reaches of the Shabeelle. Around 3,000 also settled there from the 1840s.

With the help of firearms acquired in exchange for ivory from the Sultanate of Zanzibar , the ex-slaves in Gosha subjected the bonuses to which they had initially had to pay tribute in the 1870s . In addition, they strengthened their relationships with the nomadic Somali clans (especially Ogadeni- Darod ), who moved seasonally through the area and on the one hand represented trading partners for ivory and other goods, and on the other hand initially posed a military threat to the newly founded villages. From the 1880s to the 1900s, Nassib Bundo , who came from the Yao people, established a "Goshaland Sultanate" as a political and military unit of several Bantu villages. He is traditionally praised for having won the important victory over the Ogadeni-Darod in 1890 and was recognized as a negotiating partner by an Egyptian expedition, by Zanzibar and finally by the British and Italian colonial powers. In addition to the joint struggles against Boni and Somali, there were also conflicts between the - politically and culturally largely independent - Bantu villages and rivalries between their leaders. Many villages in the Gosha were fortified at that time.

New settlers were constantly arriving in the area, and settlement in the Gosha expanded northwards into the central part of the Jubba Valley. At the same time there was an increasing "Somalization" of the Gosha residents: In contrast to the earlier settlers, those who arrived later were often forcibly enslaved as early as childhood and had lived longer in slavery, so that their ties to the area of origin were weaker and the Somali people were influenced by them Culture and society was greater. They saw themselves less as members of their Bantu peoples than as members of Somali clans and founded new villages from about north of Jilib on the model of this clan membership. Until the turn of the century Gosha-residents had virtually nationwide accepted Islam because they already either in slavery converts were, or by the action of sheikhs were Islamized and fraternities in Gosha. With the exception of the Zigula, they had switched to the exclusive use of the Somali language. Due to this rapprochement with Somali society and the "pacification" of the Ogadeni-Darod by the British colonial power, firearms and fortifications of villages largely disappeared. In the early 1900s, around 35,000 former Bantu slaves are believed to have lived along the Jubba.

Colonial times and abolition of slavery

From the 1860s onwards, Royal Navy fleets began looking for slave ships in the Indian Ocean. Slaves who were freed on such patrols and brought ashore in Somalia also settled in the Gosha. In 1875 the Sultan of Zanzibar banned the slave trade in East Africa under British pressure. Nevertheless, this trade continued at least until the end of the 19th century. In part, he shifted from the sea route to caravan routes that led via Luuq and Baardheere to the Benadir coast. From there the slaves were sold within Somalia or shipped to Arabia.

The Benadir Coast was transferred to Italy in 1892 and initially managed by private companies. In 1895 the Italian Somaliland authorities liberated a group of 45 slaves for the first time. Overall, however, they were hesitant to implement the ban on slavery because they did not want to turn influential slave-holding Somali clans against them. Sometimes they even brought escaped slaves back to their owners. This led to criticism of the Benadir Company in the Italian press in 1902 and calls for more decisive action against slavery in Somalia. From 1903 the abolition began on a larger scale and, like the entire Italian rule, gradually expanded into the interior of the country. Some groups from Bantu remained in slavery until the 1930s.

The Italians established export-oriented banana, sugar cane and cotton plantations in the Jubba and Shabeelle valleys. In the lower Jubba Valley, they expropriated 14,000 hectares of land from the Bantu. They expected to be able to use the former slaves as workers for these plantations and thus to remedy the labor shortage that resulted from the fact that hardly any Somali were willing to volunteer wage labor on the plantations. They took over the ideas of the nomadic Somali, according to which they are "naturally" unsuitable for field work, whereas Bantu is ideal. The Italians' plans suffered a setback when, after the liberation, another 20,000-30,000 ex-slaves went to the Jubba Valley instead and became independent farmers. After the fascist seizure of power in Italy, colonial policy was tightened, and from 1935 Bantu were used for forced labor . For this purpose, they were resettled in specially built villages and organized in work brigades for the more than 100 Italian plantations in southern Somalia. Land expropriation and forced labor led to widespread impoverishment and hunger, especially in the more easily accessible lower part of the Gosha. They ended with the British occupation of Italian Somaliland in 1941 in the course of the Second World War .

The two following decades (1941–1950 British military administration, 1950–1960 trustee administration by Italy) up to the independence of Somalia were largely peaceful for the Bantu, they were able to operate their agriculture relatively undisturbed by the government or their Somali neighbors. Furthermore, newcomers came to the Gosha area, albeit in decreasing numbers; Among them were Reer Shabelle , who fled from conflict in their area around Kalafo in Ethiopia from 1920 to 1960 , freed Oromo slaves (who after their release from slavery had often lived as more or less independent cattle breeders before they became farmers settled) and Somali shepherds who had lost their cattle in times of drought.

Independent Somalia under Siad Barre

The officer and member of the Marehan- Darod clan Siad Barre , who came to power in a coup in 1969, made efforts to overcome the traditional clan system and "tribalism". The Bantu benefited to a limited extent from the official rhetoric, which emphasized national unity and declared all Somali residents to be citizens with equal rights. This brought them into disrepute among parts of the rest of the population for being favorites of the Barres dictatorship. At the same time, they remained discriminated against in many ways by the state. For example, they were preferred as soldiers for the Ogad war and later fights against rebels within Somalia (forcibly) recruited because they were easy to recognize and there were fewer inhibitions about sacrificing them in the war. While some members of other minority groups such as the Midgan / Madhibaan and the Benadiri were able to rise to high posts in the state apparatus, Jarir only achieved offices at the local level.

From the 1970s, the state's interest in the previously marginal Jubba Valley and its land resources grew. With the support of international donors, extensive development projects were planned (many of which, such as the construction of the second largest dam in Africa after the Aswan Dam , were not implemented). The Land Act of 1975 declared the land to be state property and obliged farmers to acquire land titles from the state; otherwise they acted illegally and risked losing their land rights. Most Bantu farmers, however, did not have access to the laborious and costly registration process. In their place, people from outside the valley in particular acquired titles for land in the Gosha with the help of connections in the administrative apparatus, where the land of entire villages was ultimately claimed by outsiders on paper. These registered the country mainly for speculative purposes , only a small part of them actually made use of it. Bantu land was also expropriated in order to build three state farms in Marerey , Mugambo and Fanoole and to settle on these mainly former nomads and refugees from the Ogad war. These farms proved to be economically unsuccessful.

Todays situation

Way of life and culture

The Bantu in Somalia traditionally live in villages. In the upper Gosha these include one hundred to several hundred people. Mud huts are the usual dwellings. The infrastructure is sparse, most households have no electricity or running water and only few material possessions. The basis of life for the Bantu is agriculture, which they practice as small farmers on fields of an average of 0.4–4 hectares, in contrast to the Somali, who mostly live as nomads or semi-nomads from cattle breeding. The soils cultivated by the Bantu are among the most productive in the country, as they can be irrigated with water from the Jubba River. The staple food is maize, sesame, beans and various fruits and vegetables are also grown. On a smaller scale, cash crops such as cotton are produced for sale. Fish is caught in the Jubba, and dairy products and meat are traded or bought by Somali nomads. Because of the presence of tsetse flies , which transmit animal diseases , Bantu farmers rarely keep livestock. Since the 1970s, a small but growing proportion of them have settled in cities, especially in Kismayo and Mogadishu . There they usually work in poorly paid jobs with low educational requirements.

The level of education of the Bantu is low, as there are hardly any schools in the remote Gosha area, the school fees are difficult for them to raise for economic reasons and the children are also involved in field work at an early age; some also reported that they had been deliberately withheld from education. The vast majority of the Bantu refugees in Dadaab , Kenya , could not read or write. According to various reports, around 5% of adult men and almost no women, or a total of 1% of them, had a command of English .

The culture of the Bantu is shaped by the traditions of their native peoples on the one hand and the culture of Somalia on the other. The cultural ties to Bantu origins are strongest in the southern (lower) part of the Gosha - among the descendants of the earliest settlers - while the influence of Somali culture increases towards the northern (upper) part.

Like the Somali, the Bantu use the Somali language (mainly their Maay dialect), only a minority in the lowest part of the Gosha - the Zigula - have retained their original language and a distinct identity to this day. Most of them are Muslims , although many have also retained traditional religious customs. Their religious practice is traditionally moderate. The main cultural means of expression are dance and music, the Gosha area is known for its variety of traditional dances. With the Bantu in the lower Jubba Valley, belonging to “dance groups” (mviko) who perform rituals together is of great social importance. These groups are mostly organized in a matrilineal way, which is in contrast to the great importance of the paternal lineage among the Somali. The playing of the drums plays an important role in many rituals. Because women and men dance together, some local Islamic clergy speak out against the dances, but with modest success. The usual age at marriage is 16 to 18 years old - in some cases even earlier - and polygamy is common. Life in large families with high numbers of children is common. The circumcision of both boys and girls, which is widespread among the Somali, is also practiced by Bantu, whereby the circumcision of girls usually takes place in lighter forms than the infibulation usual with the Somali .

Situation in Somali society

Some Bantu groups in the Gosha have integrated into the Somali clan system by joining Somali clans. Through such connections - called ku tirsan for "to lean on" - they enjoy a certain protection against other clans, but are generally still considered a separate and subordinate group within the clan. As a rule, they participate in blood money payments for other members of the clan, while Somali clan members hardly ever contribute to corresponding payments for a Bantu clan member. They also have to accept that Somali cattle cause damage to their fields and that “their” clan takes part of their harvest, but protects them from being pillaged by other clans. Somali-Bantu marriages are very rare. They mainly occur when Somali men settle in Bantu villages and marry local women.

The Somali majority traditionally differentiate the Bantu from themselves on the basis of physical characteristics, as is expressed in the term Jarir (see section Terms and designations ). These criteria correspond roughly to what has been classified as “ negroid ” or “ black African ” in European racial theories ; For their part, the Somali do not explicitly consider themselves black Africans, but emphasize their (partly) Arab ancestry.

Furthermore, there are various prejudices about the Bantu. Her dances, for example, are known nationwide and are widely regarded as “impure” and un-Islamic; their religious integrity is generally questioned. Magical abilities such as controlling crocodiles for their own purposes are also attributed to them and are feared. As arable farmers who hardly have any cattle, they are considered particularly poor by the Somali, who value cattle breeding and nomadism.

To this day, the Bantu are considered inferior by parts of Somali society because of their jarir characteristics, their peasant way of life and because of their descent from slaves. You were and are affected by discrimination in many different forms. There was practically no political participation in the Somali state.

In this situation, the Bantu themselves mostly strived for increased integration into Somali (clan) society, not for demarcation or open resistance. Instead of banding together as slave descendants based on their shared history, they rather wanted to get over this past and the stigmatization that went with it. There was hardly any contact or even knowledge of one another between the various Jarir groups. A few Bantu with higher education tried to work for their interests on a political level. For example, a Shidle party existed under the Italian trust administration in the 1950s, but was never represented in a government. Bantu also particularly supported the HDMS , which mainly represented the South Somali Rahanweyn clan, who was disadvantaged compared to other clans , and called for a federal system in their favor . But also with the important Somali Youth League was one of the founding members, Abdulkader Sheikh Sakawadin , Jarir. In the 1980s, intellectuals founded the Somali Agriculturalists Muki Organization (SAMO). They too initially pursued the goal of being recognized as equal members of Somali society, rather than demanding more rights as a special group. This changed after the outbreak of the civil war. Under its chairman, Mohammed Ramadan Arbow , the SAMO was renamed the Somali African Muki Organization.

Overall, the events of the civil war (see below) made their inequality within and towards Somali society clearer than before from the Bantu's point of view. The international organizations and media present in Somalia in the early 1990s increasingly perceived the Bantu as a separate group that was particularly hard hit by the war. In the UNHCR refugee camps , where Somali refugees were registered according to clan membership, the “Bantu” were now categorized under this term. These factors contributed to the emergence of a new collective identity for the Somali Bantu.

In the civil war

In the civil war in Somalia since 1991, the situation of the Bantu worsened. Various warring parties, armed men and militias crossed their territory, looting food and other property and wreaking havoc on the agricultural infrastructure. Men in particular were killed if they were suspected of resisting. Rape was common. Since they had hardly any weapons and received little protection from the armed clans to which they were partly affiliated, the Bantu were particularly exposed to such acts of violence and looting. As a result, they were disproportionately affected by the war-related famine in the early 1990s . Efforts by the international community to provide them with food aid have had limited effect; Even at the time of the “ humanitarian intervention ” UNOSOM , the warring parties fought over camps inhabited by the Bantu in order to divert the aid supplies intended for them. Small children in particular fell victim to hunger in large numbers, so that in mid-1993 the proportion of children under 5 years of age in the central Jubba Valley was estimated at just 8%. (In contrast, according to UNICEF figures for 2007 , the proportion of this age group in Somalia was almost 18%.) The total number of deaths is in the tens of thousands. According to one estimate, one third of the Bantu population perished as a result of acts of violence, the indirect consequences of war, on the run or in the refugee camps ( see below ). The anthropologist and expert on the Somali Bantu Catherine Besteman described the violence that the Bantu were exposed to during the civil war as " genocidal ".

Various Somali clans and warring factions appropriated the coveted land of the Bantu in the course of the war. Some Bantu are now forced to work on what was once their land under conditions between partial lease and forced labor. Others have had to move their agricultural activities closer to the river banks, where the risk of seasonal flooding of their fields is greater. Tens of thousands have been internally displaced in Somalia or fled to Kenya. Most of the internally displaced people remain in the southern Somali region. Some made it to the northern areas of Somaliland and Puntland , where they mainly live and work in cities such as Boosaaso , Gaalkacyo and Hargeysa .

Some Bantu have meanwhile armed themselves and formed their own militias. The Islamist group al-Shabaab suppresses Bantu cultural practices such as dance, traditional medicine or religious ceremonies that do not correspond to their strict view of Islam.

refugees

Over ten thousand Bantu fled to neighboring Kenya as a result of the war . Most of them ended up in the refugee camps near Dadaab by land . There, too, they were affected by harassment and attacks by the Somali majority in the camps. A smaller part fled together with members of other minorities such as the Benadiri by sea to Mombasa and were initially housed there in refugee camps. In the late 1990s, these camps were closed and the remaining residents were relocated to Dadaab or Kakuma . After 1996, some Bantu refugees returned to Somalia, but most stated that they would never return. Instead, many expressed a desire to settle in those African countries they consider their home.

Due to a lack of financial means, hardly any Bantu reached industrialized countries to seek asylum there.

Since neither repatriation nor remaining in Kenya was an option in the long term, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) classified the Bantu refugees as candidates for resettlement in third countries. The initial plan to relocate them to Tanzania failed in 1996, as this country was already confronted with flows of refugees from Burundi and, above all, from Rwanda after the 1994 genocide . Plans for relocation to Mozambique had progressed so far in 1997 that lists of relocation candidates were drawn up. In 1999, Mozambique revoked its interest, however, because it did not have the necessary resources and had to deal with the resettlement of refugees and displaced persons from the Mozambican civil war itself .

Relocation to the USA

Finally, in 1999 , the US agreed to accept it after congressmen , representatives of refugee aid organizations and the Bantu refugees themselves had worked towards this move. This corresponds to a general tendency in refugee policy in the United States since the mid-1990s to grant asylum to entire groups of African refugees classified as particularly vulnerable, around 4,000 Benadiri and Brawanese from Somalia each in 1995 and 1996, and around 1997 and 1999 1,500 Tutsis and Hutu married with them from Rwanda and most recently in 2000 over 3,500 so-called " Lost Boys " from Sudan .

Some Somali then tried to pretend to be Bantu and thus to obtain permission to immigrate to the USA. To this end, bribed or extorted them Bantu to marriages to take, to be output as family members or obtain ration cards, they auswiesen as Bantu. As a result of such attempts at fraud, the resettlement candidates were subjected to a review process and around 10,000 were excluded from further review. Almost 14,000 people were examined more closely, of which around 12,000 were admitted. This made the Bantu the largest African refugee group to have received asylum in the USA.

Stricter security measures after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 meant that the resettlement of the Bantu refugees was delayed. They were first brought from the camps near Dadaab to Kakuma , which is considered to be safer , in 2002 by the International Organization for Migration , where they were prepared for life in the USA in courses (cultural orientation classes) . The first arrived in the USA in May 2003. They were settled in groups in around 50 cities, including around 1,000 in Salt Lake City and more in Phoenix, Arizona , Tucson , Houston , Nashville , St. Louis , Rochester , Concord, and other locations.

In some places there have been concerns about the poor education and lack of English language skills in the Somali Bantu. It was feared that it would be difficult for them to find work, that it would become a financial burden, and that school performance would decline. In the small town of Holyoke, Massachusetts , local protests prevented planned settlements. Republican Senator Sam Brownback of Kansas , who had advocated the inclusion of other groups of refugees, spoke out against the settlement of Bantu in his state of. There were further protests in Cayce, South Carolina . The fact that the Bantu traditionally practice female genital cutting , which is illegal in the USA, also caused controversy . According to reports, some parents had their daughters circumcised in the refugee camps as quickly as possible after learning of the US ban. The US authorities initially considered excluding the families concerned from resettlement. As a result of campaigns highlighting the risks of circumcision, a large number of Bantu refugees are said to have given up this practice. Critics of US refugee policy also criticized the high costs of resettlement, which they believe would be better invested in local refugee aid or resettlement to a third country within Africa.

Overall, the Bantu were positively received in their new home. The settlement of the Bantu, who had previously had little experience with electricity, running water, etc., in one of the most modern industrial countries received extensive media attention in the USA and beyond. In the media reports it is generally said that they have adjusted well to the new living conditions and, in particular, have quickly recognized the value of a good education for their children. Above all, however, critics of US refugee policy referred to the example of Lewiston (Maine) , where there are few jobs with low educational requirements, many Bantu are consequently unemployed and receive state support. From 2001, thousands of Somali and later Bantu had moved there because the place offers cheap housing and crime rates are low. According to an official report, 51% of Somali (Somali and Bantu) immigrants in Lewiston are unemployed. Since Bantu families are often very large, there were difficulties in Columbus (Ohio) in 2005 to find enough suitable housing. Numerous Bantu moved to Louisville (Kentucky) , which has a large number of jobs but has fewer and fewer workers due to the rising average age and low birth rates. At over 1,600, this place has the largest Bantu population in the United States today. Most men have jobs here, but in all cases cannot fully pay for their large families.

The relationship between Bantu and Somali remains difficult in the US as well. Somalis living in the US have supported Bantu in integrating, but some have retained prejudice against Bantu. Conversely, many Bantu are suspicious of Somali because of their experiences of slavery, discrimination and civil war. Bantu community organizations that are independent of the Somali structures have emerged in various states and localities. At the same time, both Somali and Bantu are perceived by large parts of the US public as black or African-American .

Scientific studies and figures on the integration of the Somali Bantu in the USA are not yet available.

Bantu refugees in Africa

Several thousand Bantu still live in Kenyan refugee camps.

Another group of around 3,000 Bantu, mainly Zigula, had made their way from Kenya to the Tanga region in northeastern Tanzania, where Zigula still live today. This group initially lived there in the Mkuyu refugee settlement . In 2003 they were able to move to the Chogo settlement built with the help of the UNHCR . They have been given land to set up as smallholders and they can apply for Tanzanian citizenship.

literature

- Catherine Besteman: Unraveling Somalia. Race, Violence, and the Legacy of Slavery. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia PA 1999, ISBN 0-8122-1688-1 .

- Catherine Besteman: The Invention of Gosha. In: Ali Jimale Ahmed (Ed.): The Invention of Somalia. Red Sea Press, Lawrenceville NJ 1995, ISBN 0-932415-99-7 , pp. 43ff.

- Francesca Declich: Identity, Dance and Islam among People with Bantu Origins in Riverine Areas of Somalia. In: Ali Jimale Ahmed (Ed.): The Invention of Somalia. Red Sea Press, Lawrenceville NJ 1995, ISBN 0-932415-99-7 , pp. 191ff.

- Ken Menkhaus: Bantu ethnic identities in Somalia. In: Annales d'Ethiopie. Vol. 19, 2003, ISSN 0066-2127 , pp. 323-339, online .

- Lee V. Cassanelli: The Ending of Slavery in Italian Somalia. Liberty and the Control of Labor, 1890-1935. In: Suzanne Miers, Richard Roberts (Ed.): The End of Slavery in Africa. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison WI 1988, ISBN 0-299-11554-2 , pp. 308ff.

- Lee V. Cassanelli: Social Construction on the Somali Frontier: Bantu Former Slave Communities. In: Igor Kopytoff (ed.): The African Frontier. The Reproduction of Traditional African Societies. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 1987, ISBN 0-253-30252-8 , pp. 216-238.

Web links

- Issue of the UNHCR magazine "Refugees" (3/2002) on the Somali Bantu (PDF file; 1.27 MB)

- Report on a Somali Bantu family who moved to the USA in GEO 9/2007

- "The Somali Bantu Experience" - extensive material on Somali Bantu in East Africa and the USA (English)

- Daniel J. Lehman, Omar Eno: The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture (engl.)

- Portland State University: Somali Bantu Project (Engl.)

- BBC News: New life in US for Somali Bantus (2004 )

- Simeon Chapin, Tufts University: Music of the Somali Bantu in Vermont (English, PDF file; 1.91 MB)

Individual evidence

-

↑ The Fischer Weltalmanach (2008) gives the number of 100,000. Menkhaus (2003) gives an estimate of 5 percent of the population ( online ), which would be around 350,000 with a total population of 7 million. Another estimate (quoted in The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture , 2002) gives 600,000 out of a total population of 7.5 million in Somalia. Orville Jenkins ( Profile: The Gosha. ) Puts the number of Bantu in the lower and middle Jubba Valley at 85,000. According to estimates by the UNHCR and Bantu elders from 1993, the number of those Bantu in the Jubba Valley who identify themselves mainly through their native peoples was almost 100,000 before the war, 20,000 of whom spoke the Bantu language Zigula. The CIA World Factbook names 15 percent of the population for "Bantu and other non-Somali".

For the problem of population figures for Somalia see also Somalia # Population . - ↑ Besteman: Unraveling Somalia , 1999: pp. 121, 146f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Francesca Declich: Fostering Ethnic Reinvention. Gender Impact of Forced Migration on Bantu Somali Refugees in Kenya , in: Cahiers d'études africaines , 2000 [1]

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 52f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ken Menkhaus: Bantu ethnic identities in Somalia , 2003

- ↑ a b Besteman 1999: pp. 60f.

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 62, 71, as well as Besteman: The Invention of Gosha , in: The Invention of Somalia , 1995 ("Gosha" as a geographical name)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 150 (Reer Goleed)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 116

- ↑ The Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: People ( Memento of the original dated February 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Patrick Manning: Contours of Slavery and Social Change in Africa , in: The American Historical Review , 1983 (price development and consequences)

- ^ A b Cassanelli: Social Construction on the Somali Frontier: Bantu Former Slave Communities , in: The African Frontier , 1987

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 50f.

- ↑ a b c d The Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: History ( Memento of the original dated November 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Christian Delacampagne: The history of slavery , 2004, ISBN 3-538-07183-7 : p. 226

- ^ Robert Hess: Italian Colonialism in Somalia , University of Chicago Press 1966; quoted in Besteman 1999: p. 56

- ↑ a b c d UNHCR: "Refugees" 3/2002

- ^ A b c Daniel J. Lehman, UNHCR: Resettlement of the Mushunguli, Somali refugees of southeast African origins , 1993

- ↑ The frequent mention of Nyika slaves in Somalia probably refers in part to the Mijikenda , but can also mean other ethnic groups, since (Wa) Nyika in Swahili generally means “Bushmen” or “people from the hinterland”. (Wa) Nyasa is a collective term encompassing various groups living around Lake Malawi (Lake Nyasa) and has become a synonym for slaves and their descendants, as numerous slaves came from this area (Frederick Cooper: Plantation Slavery on the East Coast of Africa , 1977, ISBN 0300020414 : p. 120). Are rarely mentioned Kikuyu , Kamba and Pokomo (ethnic groups in Kenya), Massa Inga and Makale (subgroups of Yao [2] ), Bisa , Nyamwezi , Mrima u. a. (Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos: Exodus and reconstruction of identities: Somali “minority refugees” in Mombasa ; Declich: Multiple Oral Traditions and Ethno-Historical Issues among the Gosha: Three Examples [3] (PDF)). Molema or Mlima is sometimes mentioned as an alternative name for the Somali Bantu, which means “mountain” in broken Swahili, sometimes this is also mentioned as the name of a subgroup (cf. Pérouse de Montclos and Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: People ( Memento des Originals from February 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ). Grottanelli ( I Bantu del Giuba nelle tradizione del Wazegua , in: Geographica Helvetica Volume 8, 1953 [4] ) reports on subgroups of the Zigula who call themselves Lomwe and Bena , which could indicate slaves from the ethnic groups of the same name who are in Somalia assimilated the Zigula.

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 77 (Slavery in the Bay Region)

- ^ A b Cassanelli: The Ending of Slavery in Italian Somalia , in: The End of Slavery in Africa , 1988

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 57–60 (slavery among nomadic Somali)

- ↑ On his expedition in 1865, Karl Klaus von der Betten met Zigula, who stated that they had been living in Gosha for 70 years, cf. Declich: Multiple Oral Traditions and Ethno-Historical Issues among the Gosha: Three Examples [5] (PDF)

- ↑ a b Besteman 1999: pp. 61–64 (at the beginning of the settlement of the Gosha)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 62

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 64-66

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 66–68, 74 (on the settlement of the middle Gosha)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 54f. (to shift the slave trade overland)

- ↑ a b The Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: History ( Memento of the original from November 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (to the first 45 freed slaves and some remaining in slavery until the 1930s)

- ↑ a b Besteman 1999: pp. 113–128 (Perception of Bantu by Somali and European colonial rulers, discrimination)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 87–89, 182 (forced labor, land expropriation and their consequences)

- ↑ The Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: Economy ( Memento of the original from July 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 78–90 (settlement of the upper Gosha by further ex-slaves, Reer Shabelle, Oromo and Somali 1898–1988)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 128f., 150-154

- ↑ Joint British, Danish and Dutch fact-finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya: Report on minority groups in Somalia (6.3.1; PDF; 4.5 MB)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 199–221 (Land law and state development policy and their consequences in the Jubba Valley)

- ↑ Norwegian Refugee Council, HABITAT , UNHCR: Land, Property, and Housing in Somalia [6] ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF): p. 98f. (State farms)

- ↑ UN-OCHA: A study on minorities in Somalia , 2002 (Marerey)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: p. 28

- ↑ a b c d International Organization for Migration , 2002: Somali Bantu Report ( Memento of the original from April 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: Economy ( Memento of the original from July 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Main source of this section)

- ↑ Encarnacion Pyle: Escaping Death's Shadow , in: The Columbus Dispatch , October 17, 2004 Archive link ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 6.2 MB)

- ↑ Declich: Identity, Dance and Islam among People with Bantu Origins in Riverine Areas of Somalia , in: The Invention of Somalia , 1995

- ↑ The Somali Bantu - Their History and Culture: Resettlement Challenges ( Memento of the original from April 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b BBC News: US rethinks genital mutilation threat , 2002

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 80, 141–143 ( ku tirsan and looting)

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 132–158 (Bantu reactions to their social situation)

- ↑ Besteman 1995

- ^ Virginia Luling: Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years , 2001, ISBN 978-1874209980

- ^ A b Catherine Besteman: Genocide in Somalia's Jubba Valley and Somali Bantu Refugees in the US , 2007

- ↑ Besteman 1999: pp. 3, 18

- ^ UNICEF, Statistics on Somalia ; calculated from Total population (thousands), 2007 and Population (thousands), 2007, under 5 .

- ^ A b Besteman 1999: p. 19 (By the mid-1990s, tens of thousands of people from the Jubba valley had died in the fighting or from starvation, tens of thousands still inhabited refugee camps within Somalia or in Kenya (... ).)

- ↑ L. Fraade-Blanar: Somali Bantu Cultural Orientation in Kakuma Refugee Camp: Teaching The American Mind , unpublished research paper, American University, Washington DC in 2004, cit. in Colleen Shaughnessy: Preliterate English as a Second Language Learners: A Case Study of Somali Bantu Women , 2006 [7] ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as broken. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF): p. 10

- ↑ Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 2004: Land dispossession is the main driving force behind conflict in Somalia Archive link ( Memento of the original dated September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Norwegian Refugee Council, HABITAT, UNHCR: Land, Property, and Housing in Somalia ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Pp. 49–53)

- ↑ Joint British, Danish and Dutch fact-finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya: Report on minority groups in Somalia (6.3, 6.4; PDF; 4.5 MB)

- ↑ IRIN , 2008: Somalia: Thousands displaced by fighting in Lower Juba

- ↑ Minority Rights Group: No redress: Somalia's forgotten minorities , 2010 (p. 23; PDF; 1.2 MB)

- ↑ Mohamed A. Eno: The Homogeneity of the Somali People: A Study of the Somali Bantu Ethnic Community , PhD Thesis, 2005 http://www.stclements.edu/grad/gradeno.htm ( Memento of September 12, 2007 on the Internet Archives ) (for distribution to refugee camps in Kenya)

- ^ A b Besteman / Colby College: The Somali Bantu Experience: Kenya and Refugee Camps

- ↑ Joint British, Danish and Dutch fact-finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya: Report on minority groups in Somalia (6.5; PDF; 4.5 MB)

- ↑ a b c d e Center for Immigration Studies ( en: Center for Immigration Studies ): Out of Africa - Somali Bantu and the Paradigm Shift in Refugee Resettlement , 2003

- ↑ UNHCR, 2003: Somali Bantus leave for America with hope for a new life [8]

- ^ The Salt Lake Tribune: Somali Bantu refugees started arriving in Salt Lake City, Utah

- ^ The New York Times: US a Place of Miracles for Somali Refugees , 2003

- ^ The Boston Globe, 2003: Somali Influx Gets Mixed Carolina Welcome

- ↑ BBC News: US may ban genital mutilation parents , 2002

- ↑ cf. The New York Times , 2003: Africa's Lost Tribe Discovers American Way [9] ; The Columbus Dispatch , 2004: Escaping Death's Shadow Archive Link ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 6.2 MB); Corriere della Sera , 2003: Gli Usa aprono le porte ai bantu, il popolo “dimenticato da Dio” [10] ; NZZ am Sonntag , 2003: In future, cooking will be done on the stove [11] ; Thilo Thielke: KENYA: America as a school subject . In: Der Spiegel . No. 52 , 2003 ( online - 20 December 2003 ). ; GEO 1/2004 and 9/2007 [12]

- ^ The New Yorker , 2006: Letter from Maine: New in Town , 2006 [13]

- ↑ Maine Department of Labor, 2008: An Analysis of the Employment Patterns of Somali Immigrants to Lewiston from 2001 through 2006 [14] (PDF)

- ↑ Ohio Refugee Services: Somali Bantu in Columbus - Background and local response to the Somali Bantu homeless shelter crisis in Columbus, Ohio ( Memento of the original from July 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Wall Street Journal: Bourbon, Baseball Bats and Now the Bantu - Louisville, Ky., Welcomes Immigrants to Bolster Its Shrinking Work Force ( Memento of the original from May 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 2007 (on www.louisvilleky.gov)

- ↑ Courier Journal: Somali Bantu summit opens today ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Omar A. Eno, Mohamed Eno: The Making of a Modern Diaspora: The Resettlement Process of the Somali Bantu Refugees in the United States. In: Toyin Falola , Niyi Afolabi (Eds.): African Minorities in the New World. Routledge 2007, ISBN 978-0415960922 ; see. also Letter from Maine: New in Town

- ↑ BBC News: Tanzania accepts Somali Bantus , 2003

- ↑ UNHCR: A new life begins for Somali Bantu ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 2003