Spandau municipal tram

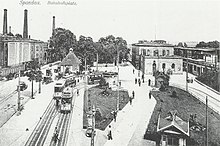

The Spandau urban tram was a tram company in the greater Berlin area . The company, founded on April 26, 1892 as Spandauer Straßenbahn Simmel, Matzky & Müller or Spandauer Straßenbahn Simmel, Matzky & Co. , opened its first horse-drawn tramway between the then independent town of Spandau and the then rural community of Pichelsdorf on June 1st of the same year . From 1894 onwards, the general Deutsche Kleinbahn-Gesellschaft was responsible for the management of the company , which introduced electric traction on March 7, 1896 . AEG was the tram operator from 1899 , and the city of Spandau from 1909. In the same year, the city acquired the Spandau – Nonnendamm electric tram from Siemens & Halske , which was completely incorporated into the Spandau tram until 1914. In addition to the routes to Pichelsdorf and Siemensstadt, there were other branches to Hakenfelde , Johannesstift and the Spandauer Bock . 1920 was the Spandau tram during the Greater Berlin Act in the Berlin tram on. The last section of the line to Hakenfelde was closed on October 2, 1967, the date also marking the end of the tram in West Berlin .

history

Prehistory, construction and opening

The first form of public transport in Spandau questioned the from 1822 trains running Torwagen of Charlottenburg and Berlin are 1846 received a Spandau on. Stresow nearby railway station (now Berlin-Stresow) at the Hamburg railway , in 1871 another at the Lehrter train . This was located on Hamburger Chaussee (today: Brunsbütteler Damm). From 1882 there was another connection to the Berlin light rail via the Hamburg light rail connection . The first approaches to inner-city local transport came towards the end of the 1870s. On September 6, 1876, the agricultural citizen Ludwig Schultze submitted an offer to the city to build a horse-drawn railway between Spandau and Pichelsdorf. Since the applicant did not submit any detailed plans, the magistrate rejected the project. On August 1, 1877, the Spandau merchant August Voigt set up a horse-drawn bus route between the Hamburger Bahnhof and Pichelsdorf , which only existed for a short time. In November 1879 the haulier Gaede set up another connection between the Lehrter train station and the Schülerberg barracks on Schönwalder Strasse . In February 1880 he discontinued the line, which had twelve daily trips, due to a lack of profitability. In 1885 Voigt applied for the concession for a horse-drawn tram from Pichelsdorf via Lehrter station to the Schülerberg barracks and a branch from Potsdamer Straße (today: Carl-Schurz-Straße) via the market to the rifle factory on Zitadellenweg with the option of an extension to the Spandauer Bock . Due to a lack of detailed plans, this project also failed.

The plans for the construction of the horse-drawn tram took shape in 1889, when Spandau exceeded the population of 40,000. Plans for a municipal tram, like the one running in Cöpenick since 1882 , failed because the share certificates subscribed by private individuals only covered around half of the targeted costs of 300,000 marks (adjusted for purchasing power in today's currency: around 2.23 million euros). The magistrate then worked out conditions for the concession, for which two applicants applied. For the electrical variant, this was the US Thomson-Houston Electric Company . After the Spandau residents had convinced themselves of the usefulness of the electric train using the example of Halle (Saale) , negotiations were started with the company's Berlin representative. In the meantime this showed no more interest in the implementation, so that the city got closer to the horse tram project.

The concession was originally intended to be granted to the Halle entrepreneur Georg von Kreyfeld , who opened the Friedrichshagen tram in 1891 . Since he hesitated with the construction, the city council decided in agreement with Kreyfeld that the concession should be transferred to a consortium to which the Spandau businessmen Simmel and Matzky belonged. The first line from the passenger station (formerly: Hamburger Bahnhof) to the Fehrbelliner Tor should be completed by July 1, 1892, the second line from the station to Pichelsdorf, which was more complex because of the level crossing of the Hamburger and Lehrter Bahn, should be completed at a later date consequences.

From mid-May 1891, over 100 workers began building the double-track line from the start. To enable smaller radii in the narrow streets of the old town of Spandau , the gauge should be 1000 millimeters . The route began at the passenger station (from 1911: Spandau Hauptbahnhof) and led via Stresowplatz , Charlottenbrücke , Breite Straße , Havelstraße , Neue Brücke, Neuendorfer Straße , Hafenplatz and Schönwalder Straße to the Fehrbelliner Tor. In the opposite direction, the trains ran over Potsdamer Strasse and Markt instead of Havelstrasse. The car hall was located at Schönwalder Strasse 43/44.

Since construction work in the city center was delayed, the section between Neuer Brücke and Fehrbelliner Tor went into operation on Saturday, June 4th, 1892. On the following Pentecost Sunday, the grand opening of the Spander tram Simmel, Matzky and Co. took place. During the holidays, more than 6,000 people used the new means of transport. Between June 11th and 16th the route was extended to the market . After the police inspection on June 24th, the entire line could go into operation on June 26th, 1892. Although there were no designated stops , the coachmen were instructed to stop only at certain points for passenger changes . By July 12, 1892, the tram had already carried 102,000 passengers; by October 9, 1892, their number had risen to around 360,000. In excursion traffic on the weekends, there were around 7,000 to 8,000 passengers a day compared to around 5,000 passengers on weekdays.

The second line to Pichelsdorf went into operation in three stages in 1894. The first section, including the new depot at Pichelsdorfer Strasse 83, was used from June 24, 1894. The section began at the intersection Klosterstraße corner Hamburger Straße south of the Lehrter train and ended on depot. Initially, two horse-drawn trams drove on the section. After the transfer of four more wagons, the southern continuation to the border to Pichelsdorf could go into operation on July 1, 1894. After the tracks had been laid through Potsdamer Strasse and connected to the existing line, the police inspection took place on August 30, 1894, which was followed by the commissioning of the entire line one day later. Although the area crossed by the line only had around 7,000 inhabitants at that time - in contrast to the first line with around 30,000 inhabitants in the catchment area - it was relatively well frequented. The Berliners in particular used the line on Sunday excursions to Unterhavel and Pichelswerder . According to the Spandauer Anzeiger for Havelland , around 5,000 people were supposed to have been transported on July 7, 1894 alone.

With a contract dated November 19, 1894, the Allgemeine Deutsche Kleinbahn-Gesellschaft took over the railway on the basis of the Prussian Kleinbahngesetz .

Electrification and re-gauging

In the mid-1890s, the technical development of the electric tram had advanced so far that the Spandau magistrate once again pursued the electrification of the horse-drawn tram. The Allgemeine Electrizitätsgesellschaft was won over to equip the railway . The power supply was therefore via roller pantographs . The power station was built on the site of the depot on Pichelsdorfer Straße. In August 1895, the erection of the masts and the subsequent assembly of the overhead line began . Where the development allowed, wall rosettes were alternatively used to secure the lines.

The police inspection of the railway was on March 7th, 1896. An objection from the Oberpostdirektion initially prevented the start of electrical operation, as it feared that the telephone cables would be impaired by stray currents . After safety devices were put in place on the telephone systems, operations could finally begin on March 18, 1896. A few days later, on April 1, 1896, the third route along Neuendorfer Strasse went into operation. It began at the intersection of Schönwalder Strasse and the Schützenhaus on the corner of Schützenstrasse . Initially a shuttle car drove on the line from Schönwalder Strasse, later the line went to the train station. Like on the other two lines, the wagon sequence was eight minutes on weekdays. On Sundays, the trains ran the route every eleven minutes, on the other lines every six minutes. With the introduction of the winter timetable in 1896/97, the two older lines ran every eight minutes, the line to the Schützenhaus every twelve minutes. From 1903, all three lines ran every eight minutes. The line's cars were given green destination signs. The railway station - Fehrbelliner Tor line was given white ones, the railway station - Pichelsdorf line colored red.

With a contract dated March 4, 1899, the Spandau tram was transferred from the Allgemeine Deutsche Kleinbahn-Gesellschaft to AEG. The license was transferred by the government on March 27, 1899, by the city of Spandau on September 14, 1899. In 1900 the workforce comprised three office clerks, six employees for the power station, 19 workshop and route workers, three conductors and 27 drivers as well as 48 auxiliary conductors and drivers. The track length was 13,683 meters. The car fleet amounted to 24 multiple units and 20 sidecars. In addition, horses were still available for the transport of night cars, as the power station probably did not work continuously. The night cars drove on the “green” and the “red” line on weekdays with one round trip each and on Sundays and public holidays with two in quick succession. The number of people transported (excluding subscribers) was 1,954,604 that year.

| Line 1 | signal | course | Cycle (in min) |

Length (in km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. |

|

Train station - market - Fehrbelliner Tor | 7½ | 2.71 |

|

|

Train station - market - Fehrbelliner Tor - city park | 15th | 3.64 | |

| II |

|

Train station - market - Pichelsdorf | 7½ | 3.86 |

| III |

|

Train station - market - rifle house | 7½ | 2.22 |

|

|

Railway station - market - Schützenhaus - Hakenfelde | 15th | 3.98 | |

|

1 The Roman numerals for the line numbers were only given in the timetables.

|

||||

The next extension of the route went into operation on November 22, 1901 and comprised the 930 meter long section from the Fehrbelliner Tor with the crossing of the war railway to the Stadtpark on Reichstrasse . The route led through largely undeveloped land and was primarily used to develop the Spandau city forest, the southern part of which was to be developed into a park - hence the name city park. Every second car on the line that previously ended at Fehrbelliner Tor drove through to the city park, which corresponded to a train of cars of 16 minutes. The trains were given yellow signs to distinguish them.

In 1900, the Berliner Grundrentengesellschaft in Hakenfelde, east of Streitstrasse, acquired land with a total area of more than 60 hectares in order to use it for industrial purposes. From 1901 to 1904 the company widened several streets and the Streitstraße to 30 meters. They provided the new streets with freight tracks and built the Maselake Canal as a branch canal to the Havel . The as Industriebahn hook field called industrial main track was in Spandau Johannesstift connected to the rest of the rail network. The city of Spandau wanted to open up the area by tram, while AEG was skeptical of the project. The agreements made with the city finally forced AEG to extend the green line from the Schützenhaus to Hakenfelde to the intersection of Streitstrasse and Mertensstrasse . In advance, the existing line to the Schützenhaus was expanded to two tracks in 1902 and 1903. The new line was opened on May 21, 1904, and here, too, only every second car drove to the new terminus. It was single-track with two switches at Sonnenhof and Goltzstrasse . The industrial area did not develop to the desired extent, but there was a brisk residential construction activity along the Streitstrasse, which was intensified by the tram.

As early as 1896, the AEG was planning a tram route from Spandau to Westend , which has not yet come about due to various problems. The Charlottenburg Gate and the bridge over the Schlangengraben were too small for the railcars, and the Hamburger Bahn at Stresowplatz and the Lehrter Bahn at Ruhleben had to be crossed at the same height. After softening Spandau in 1903 the city the following year was to expand the failing Grunewaldstraße, demolish the Charlottenburg Gate and replace the bridge over the Snake digging through a wider wooden structure. The work also served the installation of tracks for a route to the Spandauer Bock , where there was a connection to the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram . Agreements have been made with the Royal Railway Directorate in Berlin regarding the level crossings. For its part, AEG now showed no interest, since it did not expect high income from the route leading through largely undeveloped land, which would guarantee an interest on the investment capital. In order to keep the construction costs low, the company intended a direct tour via the Freiheitswiese, whereas the city wanted the detour via Grunewaldstraße and achieved it after granting grants.

When the preparations for the trestle line became concrete, the AEG reached an agreement with the magistrate to implement the new route in the standard gauge immediately and to re-route the rest of the network promptly in order to enable a later connection to the Berlin tram network. The trestle line, which opened on July 1, 1906, was initially operated independently of the rest of the network; the three railcars were housed in a temporary wagon hall at the intersection of Ruhlebener Strasse and Grunewaldstrasse not far from the Schlangengraben. Until 1911, the fare for the Bocklinie was higher than that of the other lines. The 3.66-kilometer-long, single-track line began at the plantation south of the Hamburger Bahn and led via Grunewaldstrasse and Charlottenburger Chaussee to the Spandauer Bock excursion restaurant. The track ran continuously on the southern side of the track, only in Ruhleben it changed to the middle of the track. Before the city limits of Spandau, the line crossed the Lehrter Bahn at the same level. The last 400 meters were in the Charlottenburg area. There was no track connection to the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram, despite the same gauge and power supply, as the terminal stop was on a ramp, while the Spandau tram was at street level. The line ran every 15 minutes during the day.

Also in 1906 began work on re- gauging the remaining sections of the route, at the same time the Royal Railway Directorate in Berlin raised the Hamburg railway from Spandau station to behind Klosterstrasse. The red line to Pichelsdorf therefore had to be divided on Klosterstrasse for a long time. The work was carried out in such a way that one track was re-gauged in sections, while the remaining track was shuttle service. From April 29, 1907, the lines in the direction of Hakenfelde, Stadtpark and Pichelsdorf am Markt, from where shuttle cars drove to the train station, began and ended. In mid-May the railway overpass at Klosterstrasse was completed and the Pichelsdorf line was able to run continuously between Markt and Pichelsdorf on standard gauge tracks. From May 16, the line ran in standard gauge to Brückenstraße, and the station should have been reached from May 19. Until the second track was put into operation on June 9, 1907, passengers had to change trains several times. Work on re-gauging the lines to the city park and to Hakenfelde began at the end of May 1907. As with the Pichelsdorf line, a single-track shuttle operation took place while the second track was being renovated. From July 6, 1907, the first regular-gauge sections could go into operation. Narrow-gauge operation existed on the Schützenhaus - Hakenfelde section until August 19, 1907, while the single-track Fehrbelliner Tor - Stadtpark section was completely closed from July 6, 1907 to July 19, 1907. The section from Markt to Havelstrasse in the old town was rebuilt between August 19 and 29, 1907, during which time a shuttle service had to be set up again between the market and the train station. The network reconstruction was completed on August 30, 1907, and the police inspection took place on October 10, 1907. After the Hamburg railway had been raised, the trestle line was extended to Stresowplatz on July 20, 1907, where there was a track connection to the station - market line.

During the renovation work, on the evening of May 1, 1907, a serious accident occurred at the level crossing in Charlottenburger Chaussee in Ruhleben, in which a freight train caught the fully occupied railcar 72 and smashed it. Two passengers were killed in the incident. As a result, the trams were no longer allowed to cross the level crossing, passengers had to pass the crossing on foot. The railcars were only allowed to drive unoccupied at the crossing for overpasses in the morning and in the evening. The line could be operated continuously from September 29, 1907, after the tram administration and the Royal Railway Directorate Berlin had agreed on the provision of an additional barrier post.

After the gauging, minor changes were made to the side and destination signs of the cars. In the future, the side signs showed the entire course of a line, even if it took a shortened route, the destination sign corresponded to the actual final stop. By purchasing more cars, the Pichelsdorf line was able to run every six minutes from November 1907. The increase in the number of trains was a necessity, since no sidecars could be used during the week because there were no conductors.

In the spring of 1908, work began on the double-track expansion from the Fehrbelliner Tor to the city park and the construction of a subsequent single-track line to the Johannesstift . The second track was on 28 August 1908 in operation, the new line shortly afterwards on October 1, 1908. The new line received the letters J . Since the eponymous Johannestift did not open until two years later, a train of cars of 18 minutes was sufficient in the beginning. The construction of the route was a concession by the city to the monastery in order to persuade it to move from Plötzensee to the new location. In order to make the individual lines more recognizable, the management decided in the summer of 1908 to introduce line names instead of colored signal lamps. The lines were named after the Chemnitz model with the first letter of the destination out of town, whereby the city park line was given the abbreviation St to differentiate the line to the Schützenhaus (line S ) .

Communalization

The city of Spandau declared to the AEG in 1905 that it was ready to extend the license , which originally ran until December 31, 1942, by 15 years until the end of 1957. A short time later, the electrical company expressed its intention to transfer the tram to a public company. Negotiations between the two sides followed to acquire the railway through the city. On September 7, 1906, the city acquired the tram for a purchase price of 3,350,000 marks; the handover was set for July 1, 1909. During this period, AEG was still obliged to add new vehicles to the fleet, but the city had to pay for special requests. After the localization of the railway, the concession was valid until June 30, 1999.

As early as 1900, the city intended to build a mixed freight and tram from Spandau via Haselhorst to Charlottenburg to connect East Spandau and the exclave Nonnendamm (from 1914: Siemensstadt ). The high costs of 530,000 marks initially let the project disappear into the drawer. When a few years later the companies Siemens & Halske (S & H) and Siemens-Schuckertwerke (SSW) set up their factories on Nonnendamm, they took up the project again and realized both the Siemens freight railway - opened on March 16, 1908 - by 1908 - as well as the electric tram Spandau – Nonnendamm ("Nonnendammbahn") - opened on October 1, 1908 - to connect the plants. In the same year, the area between Spandau and Nonnendamm was incorporated into Spandau. The Nonnendammbahn, operated by Siemens, ran from the intersection of Nonnendamm and Reisstrasse over the Schwarzen Weg (today: Paulsternstrasse) and today's Gartenfelder Strasse and ended at the intersection of Berliner Strasse and Breite Strasse. It was initially without connection to the city tram. In the spring of 1909, the tracks of both railways were linked so that the trains on the new line could turn over Havelstrasse, Potsdamer Strasse, Markt and Breite Strasse. The track width of 1435 millimeters and power supply via roller pantographs corresponded to that of the city tram, so that a wagon transfer was possible without any problems. To hand over the tram to the city, S & H and SSW founded the Elektro Straßenbahn Spandau – Nonnendamm GmbH on March 23, 1909, whose shares in the amount of 300,000 marks were sold to the city of Spandau on October 1, 1909. The purchase price totaled 463,000 marks. The joint routes with the Siemens freight railway remained with Siemens.

In 1909, with the exception of the level crossing in Ruhleben and a short section in the Charlottenburg area, the trestle line was expanded to two tracks. In August 1909, shunting tracks to the south of the main entrance were put into operation for the special train service to the Ruhleben trotting track . In October 1909, the elevation of the Hamburger Bahn began in the area of the Spandau station, which entailed a reconstruction of the station forecourt. The previous butt end point was replaced by a turning loop that went into operation on November 10, 1909. On April 1, 1910, the municipal tram took over the management of the Nonnendammbahn, the tram company formally existed until October 1, 1914. From this point on, the railcars were located in the depot on Pichelsdorfer Straße to enable a more efficient way of working with repairs. The less maintenance-prone sidecars were still housed on the Grenzstraße until the summer of 1910. From May 1910 to Nonnendamm running trains received the line marks N , the Black Army to cannery at the Gartenfelder street corner route led the letter C , by May 1911 letter K . The latter ran mainly on Sundays, as the trains continued to Nonnendamm on weekdays.

Urbanization brought the city treasury little or no surplus. In particular, the Bocklinie and the Nonnendamm turned out to be problem children of the company, as they led over long sections through largely uninhabited areas. The Bocklinie obtained its income mainly from the Sunday excursion traffic. The Nonnendammbahn, on the other hand, was in great demand during rush hour - the trains often ran with three cars - and was used by passengers with discounted workers' weekly tickets. The surpluses of the other lines therefore had to compensate for the deficit of the Nonnendammbahn. The city made several far-reaching decisions in an effort to bring improvements to passengers and increase fare income. On September 16, 1910, the city extended the Bocklinie into Spandau's old town, where it ran along the block loop at Breite Strasse / Havelstrasse / Potsdamer Strasse / Markt. The final stop was the Neue Brücke at the corner of Havelstrasse and Neuendorfer Strasse.

On January 1, 1911, there were major changes as part of a tariff adjustment. The previously applied ten-pfennig standard tariff has been replaced by a zone tariff and lines B, K and N, which are treated separately in the tariff, are included in this tariff. On weekdays, the train now used conductors in the car after they had only been used on Sundays. During the week, the railcars ran in one-man operation with payment boxes , which the driver took over control. The increasing number of passengers meant that they were permanently overwhelmed with the controls and the number of fare dodgers increased. The decisive factor in hiring the conductors, however, was a request by the Royal Railway Directorate in Berlin for posts at the intersections with the Lehrter Bahn in Klosterstrasse and Charlottenburger Chaussee. These should, for example, use the pantograph rods again if the contact roller slips off the overhead line. In addition, the hiring of the inspectors made it possible to expand the transfer options. At the beginning of 1911, the city hired 66 conductors, whose total wage costs amounted to 77,484 marks. After the completion of the six-track expansion of the Hamburg Railway in the course of the elevation, the Lehrter Railway between Ruhleben and Klosterstraße was shut down in 1912.

On May 1, 1911, the municipal tram extended lines K and N from the old town via Potsdamer Strasse and Seegefelder Strasse to the corner of Staakener Strasse at Spandau West station . The route should form the prelude to the connection of the western district of Klosterfelde . On November 1, 1911, line N was extended from Nonnendamm via Reisstrasse and Rohrdamm to Fürstenbrunn to the north bank of the Spree , where there was a footpath to Fürstenbrunn station on the Hamburger Bahn via Siemenssteg . The new line mainly benefited the Siemens works workers who lived in Berlin and Charlottenburg. Also from November 1911 on Sundays, the S line continued as line H to Hakenfelde and the F line continued as line St to Stadtpark. The last line opened before the First World War was on January 8, 1912, the connection from the Army canning factory to Gartenfeld to the Siemens cable factory. The branch line was only served by a newly established line G (Gartenfeld - Fürstenbrunn) during the shift change.

On April 1, 1913, in addition to a renewed change in fares, lines B and St were merged to form the new line B (Spandauer Bock - Stadtpark). Line F was no longer mentioned in the timetables, line K followed six months later on October 1, 1913. The commissioning of the tram route from the Jungfernheide ring station to the administrative border on Ohmstrasse on October 1, 1913 had far-reaching consequences for traffic to Nonnendamm and the extension of line 164 of the Great Berlin Tram (GBS) to Ohmstrasse on February 1, 1914. The residents of Siemensstadt and employees of the Siemens administration building then used this connection with a change in Jungfernheide, as only the reduced city and ring rail tariff had to be paid on the railroad. The workers at the Gartenfeld cable plant were initially unaffected. With the extension of line 164 from Ohmstrasse to in front of the Siemens administration building on June 9, 1914, the picture changed here too, as the garden field workers preferred the one and a half kilometer walk from the administration building to the cable factory. S & H and SSW jointly acted as a tram company under the Prussian Small Railroad Act for the approximately 1.3-kilometer section of the route . The route followed the Nonnendammallee (formerly Nonnendamm) and ended about 350 meters west of the administration building in a single-track turning loop. Between Reisstrasse and Rohrdamm the tracks of the Spandau tramway were also used, from the Rohrdamm onwards the facilities were four-track with one pair of tracks each for the lines of the Spandau tramway and the GBS line. The Berlin-Charlottenburg tram , a subsidiary of GBS, took over the management of the Siemens tracks .

First World War and Greater Berlin Law

The beginning of the First World War also resulted in considerable restrictions on the Spandau municipal tram. Line G was discontinued until September 1914 and the sequence of cars on the other lines was extended to 15 minutes - on line N to 30 minutes - individual sections of the route were without traffic. Since the suburban trains to Berlin ran irregularly, lines H and J were instead extended from the main train station to Spandauer Bock in order to offer more frequent transport to Charlottenburg and Berlin. As a result of the hiring and training of female conductors and drivers, all endpoints could be reached again from August 29, 1914, and the cycle times were slightly compressed. The timetable of November 8, 1914 listed the existing lines according to the last peace timetable, but was subject to far-reaching changes in January 1915. Line J was withdrawn from Johannesstift to Fehrbelliner Tor and in its place line B was extended from Markt to Johannesstift. Line N ended on the market from June 20, 1915 to August 31, 1915 and again from October 28, 1915 to November 30, 1915. Line S was discontinued on December 1, 1915, with line H being compressed to a 7.5-minute cycle. In November 1915, the city recruited around 60 tram drivers and technical employees from Switzerland to meet the continued high demand for drivers and workshop personnel; no information is available about the duration of their deployment.

On January 15, 1916, the Charlottenbrücke collapsed after a ship had rammed it. Because of the interruption, the lines that would otherwise run to the main train station ended at Bahnhof West (line H), at the Neue Brücke (line P) and on the Lindenufer west of the Charlottenbrücke (line J). Line B ran in two parts from Johannesstift to Lindenufer and from Stresowplatz to Spandauer Bock. A pendulum line served the section from the east bank of the Charlottenbrücke to the main station. From February 21, 1916, a new line S ran between Weverstrasse (street station) and Schützenhaus at times of low traffic. By June 1916, soldiers from Pioneer Battalion 3 Rauch had built a makeshift bridge south of the damaged structure ; the trams used it from August 6, 1916. When it was put back into operation, line B was withdrawn to the Neue Brücke and line St between the main station and the city park was re-established . Lines H and S will in future run in both directions through Potsdamer Strasse instead of through Markt, Breite Strasse and Havelstrasse as before.

Persistent capacity bottlenecks among workshop personnel led to renewed restrictions in the timetable on February 7, 1917. Lines J and S were discontinued that day, line H to Stadtpark, line P to the tram station and line B to Stresowplatz withdrawn. At the same time, the wagon sequence was thinned out on all lines. Only the Nonnendammlinie remained unaffected by the measures. To compensate for the shortage of cars, the tram administration tried to get vehicles from other cities. In addition to two sidecars rented by Woltersdorfer Straßenbahn , a total of 13 powered rail cars and a further six sidecars from Kaiserslautern , Schwerin and probably Neunkirchen were acquired by spring . The increased fleet of vehicles made it possible in June 1917 to repeal the measures decided in February.

| Abbreviation (old) |

Number (new) |

course |

|---|---|---|

| St. | 1 | Central station - market - city park |

| J | 2 | Central station - market - city park - Johannesstift |

| H | 3 | Central station - market - Schützenhaus - Hakenfelde |

| P | 4th | Central station - market - tram station - Pichelsdorf |

| N | 5 | Market - Siemensstadt - Fürstenbrunn |

| S. | 6th | Tram station - Schützenhaus 1 |

| G | 7th | Gartenfeld - Siemensstadt - Fürstenbrunn 2 |

|

1 Line was not in operation at the time of the changeover

2 Time of restart not known

|

||

In the spring of 1917, the direct tram connection to Berlin was established under the pressure of war. The impetus was provided by the Army Administration, which wanted a connection from Berlin to the Spandau armaments factories as free as possible. In return, the army administration contributed financially to structural measures, such as the creation of a track connection on the Spandauer Bock. In the old town of Spandau, four arches had to be widened so that the longer four-axle cars of the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram could use them. In the Triftstraße a two-pronged went reversing facility in operation. From May 13, 1917, lines P (previously: Bahnhof Neukölln - Westend , Spandauer Chaussee / Kirschenallee ) and R (previously: Neukölln , Wildenbruchplatz - Spandauer Bock) continued from Spandauer Bock like line B to Hafenplatz and from there via Neuendorfer Straße to Triftstraße. The travel time of the Berlin-Charlottenburg line P after the extension was 100 minutes with a line length of 23.3 kilometers, that of the line R 93 minutes with a line length of 21.5 kilometers. The trestle line for its part was discontinued. As the line designation "P" was duplicated as a result of the extension, the city of Spandau introduced Arabic numbers as line numbers for its lines from the end of July. The former line J, now run as line 1, was discontinued on August 27, 1917, except for a morning journey, and line 2 (formerly: St ) was compressed to a 7.5-minute cycle. From January 10, 1918, the section between Stadtpark and Johannesstift was without service. At the same time, the Berlin-Charlottenburg line N (previously Kupfergraben - Charlottenburg, tram station) was extended to Triftstrasse on Sunday afternoons in order to cope with the constant excursion traffic. On weekdays, individual early morning cars also drove through to Spandau.

Due to the numerous armaments companies and the Siemens works, the number of passengers on Line 5 was above average. However, the predominantly single-track route proved to be a bottleneck. In order to increase the number of wagons, a single-track direct connection on Nonnendammallee between Gartenfelder Straße and Schwarzer Weg went into operation on January 21, 1918. The line is said to have run over a newly laid track parallel to the Siemens freight railway , but other sources report that the freight tracks were also used. The trains from Spandau to Siemensstadt ran on the new line, the trains in the opposite direction on Schwarzer Weg and Gartenfelder Strasse. From the same day on there was another continuous connection to Charlottenburg and Berlin. Spandau lines 5 and 7 continued from the Siemens administration building via Siemensdamm and Nonnendamm to the Jungfernheide ring station . The branch to Fürstenbrunn, which has been underutilized since 1914, was closed on the same day. There were also loop trips between the Jungfernheide ring station and the powder factory in Haselhorst (Nonnendammallee and Gartenfelder Straße), which were run as line 8.

After the end of the war, the Spandau tram stopped lines 6, 7 and 8 by September 1919 at the latest due to the decline in demand. From March 3, 1920, one train each morning and noon drove back to Johannesstift. In the same year, the line in Neuendorfer Strasse received its second track. The last new opening concerned the extension of lines 3 and 5 from the Spandau West train station through Seegefelder Strasse to Nauener Strasse on November 1, 1920. It was planned to extend the line to Staaken ; For this purpose, tracks had already been laid in Nauener Strasse at the underpasses of the Hamburger and Lehrter Bahn. These stayed there until the 1960s. Other plans concerned the extension of the Hakenfeld line to the “Wilhelmsruh” restaurant and the connection to the In den Kisseln cemetery . In view of the poor operating results of the Bocklinie and Nonnendammbahn, the city refrained from further planning in areas that were still to be developed.

The Spandau tram as part of the Berlin network

As early as October 1st, the city of Spandau was incorporated into Berlin as a result of the Greater Berlin Act . The city of Berlin came into possession of the Spandau tram. On December 8, 1920, the Great Berlin Tram took over the Spandau Tram. After the merger of GBS with the Berlin urban tram and the Berlin electric tram five days later, this became the Berlin tram .

The takeover was only noticed externally in the course of 1921. The vehicles gradually received new company numbers. On April 1st, the line network was reorganized and line numbers were reassigned. The formerly the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram, which was incorporated into the GBS in 1919, lines P and R also took over the tasks of lines 3 and 4 and were extended from the old town to Hakenfelde and Pichelsdorf. The final stop on Triftstrasse has been abandoned. Line 6, which was discontinued in 1919, was re-established as line S between Hakenfelde and the tram station. Lines 2 and 5 were given the numbers 20 and 35, but kept their routes.

The Spandau tram network remained largely unchanged in the following years. The line through Nonnendammallee, opened in 1918, was closed in favor of the double-track expansion in Gartenfelder Straße and Schwarzen Weg. From 1923 to 1945 there was a transition to the Bötzowbahn to Hennigsdorf in Johannesstift , which was operated by a new line 120 . From 1927 there was a third connection between Spandau and Charlottenburg via Heerstraße. From 1928 the tram drove from Mertensstraße to Eschenweg to connect the newly created forest settlement Hakenfelde , for better The plans continued to provide for the connection to Staakens and the cemetery in the Kisseln, a new connection was from Gartenfeld to Tegel and from Spandau and Pichelsdorf over Gatow to Kladow . None of the projects got beyond the planning stage.

After the decision to discontinue the tram in West Berlin , the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe closed the sections of the former Spandau tram starting in 1960. On October 2, 1967, the last tram in West Berlin ran from Zoo station via Jungfernheide station and Siemensstadt to Hakenfelde.

Tariff

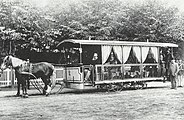

The fare for the horse-drawn tram was ten pfennigs for a single journey . The passengers had to drop the fare into a glass payment box , which the driver checked. Conductors drove with the excursion traffic on Sundays because of the greater number of visitors. After the electrification, the fare initially remained the same and also entitle you to change trains. The passengers had to report to the switchmen posted at the transfer points for control. The conductors' assignment was extended to night trips from 11:30 p.m. Separate tickets were issued for transfer journeys by the conductors. Children under four years of age rode free of charge when accompanied by an adult, provided they did not occupy a separate seat; On the Bocklinie, which opened in 1906, a single trip cost ten pfennigs on weekdays. On Sundays the fare for the same route was 15 pfennigs, at the same time there were two sections of ten pfennigs. Even after the extension to the station, the separate tariff remained, so there was no authorization to transfer to other lines. Conductors were initially employed on the line before the payment box system was introduced on weekdays on February 1, 1907. A single trip on the Spandau – Nonnendamm tram cost ten pfennigs, from August 15, 1909, there was a transfer authorization to the other lines in the direction of Spandau, but not in the opposite direction.

On January 1, 1911, there was a major tariff adjustment. The payment box system was abandoned in favor of the permanent use of conductors. Instead of the standard price of ten pfennigs, the railway introduced a zone tariff. The first zone extended from the market as the center of the city to the main train station , the plantation, Hamburger Strasse , the Spandau West train station , the port square and the storey factory. The second zone extended to Fehrbelliner Tor , Hohenzollernring , Berliner Chaussee at the corner of Nonnendamm, Tiefwerderweg and Wilhelmstrasse . The third zone extended to the city park, to Hakenfelde , to the Ruhleben trotting track and to Pichelsdorf . The fourth zone finally extended to Johannesstift , Nonnendamm and Spandauer Bock . A journey through three zones cost ten pfennigs, each journey beyond that cost 15 pfennigs, whereby the journey through zone I was not included. At the same time, the railway issued monthly tickets for a different number of lines. The connections were considered to be lines in the tariff sense:

- Central station - Johannesstift

- Central station - Pichelsdorf

- Central station - Nonnendamm

- New Bridge - Spandauer Bock

- West station - Nonnendamm

Seven marks were to be paid for one line, ten marks for two lines and 12.50 marks for the entire network. Student monthly tickets cost 3.50 marks, but were only valid until 6 p.m. Weekly worker tickets for people working in Spandau cost 60 pfennigs and entitle them to two journeys, six days a week. In addition to the season tickets, bundle tickets (25 pieces for one mark) were also issued. Two notes had to be stamped for a ten-pfennig route and three for a 15-pfennig route. As early as April 1, 1911, the bundle tickets were abolished and the fare for the workers' weekly ticket was raised to 80 pfennigs for ten pfennig routes and one mark for 15 pfennig routes. Instead of the monthly student cards, the administration issued snap cards for 15 trips at one mark.

The next tariff increase was on April 1, 1913. The ten-pfennig fare was now valid for two zones, journeys through three zones would cost 15 pfennigs in the future, and 20 pfennigs beyond that. The fare for the monthly tickets was reduced to six marks for one line and one mark more for each additional line. For workers there were now twelve-trip tickets for one mark valid for ten calendar days and monthly tickets for all lines at five marks (valid on weekdays) and 5.70 marks (valid on all days).

On May 13, 1917, lines P and R of the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram , which were extended to Spandau , were subject to a single fare of 35 pfennigs for the entire route; partial-distance tickets were issued for 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 pfennigs. In the course of 1918, the onset of inflation led to a renewed increase in the single fare. From May 1, 1918, a single journey cost 15 pfennigs, and from February 1, 1919 it cost 20 pfennigs. By December 1st, 1920 the price rose to 60 pfennigs. From February 1, 1919, the transfer authorization was newly introduced. On October 19, 1919, the bundle tickets were replaced by trading cards; from April 1, 1920, monthly tickets were no longer issued. After the takeover by the Berlin tram, a separate tariff was still in effect until June 22, 1922.

Driving operation

vehicles

Information about the fleet of Spandau trams differs in some cases.

When the Spandau tram opened in 1892, there were two closed single - carriage vehicles (No. 3 and 4) with twelve seats and five standing places, as well as two two -horse summer carriages (No. 1 and 2) with twelve seats and six standing places. In the same year two more single horses (No. 5 and 6) were added. According to Kämpf, eight carriages and 30 horses are said to have been available by July 1892, and by the end of 1893 twelve carriages and 40 horses were available. The vehicle listings, on the other hand, show six cars for the opening year and a higher number from 1894. After the railroad was sold to Allgemeine Deutsche Kleinbahn-Gesellschaft AG (ADKA), it increased the stock to a total of 20 cars (no. 7–13, 14–20) following the commissioning of the Pichelsdorf line. After the start of electrical operation, the draft horses were sold for 500–600 marks each, which corresponded to around 60 percent of the purchase price.

On October 20, 1895, the first of a total of 24 railcars (No. 21-44) and seven sidecars (No. 1 II -7 II ) for electrical operation arrived in Spandau. The red-brown painted cars each had 16 seats lengthways with standing room for twelve and 20 hp drive motors. Similar cars of this type manufactured by Herbrand also ran in Essen , Kiel and Altenburg , among others . 13 of the former horse-drawn tram cars were used as sidecars. Until 1901, the night car still ran with a horse-drawn carriage. Two horses were still available for this. For the extension to Hakenfelde , the railway procured another ten trailer cars (No. 20 II -29 II ), at the same time the older railcars were assigned the number series 40-63. At the end of 1905 there were 24 railcars and 26 sidecars, around half of the cars came from the horse-drawn tram.

In the course of the change of gauge to standard gauge 1906-1908 a further 13 railcars (No. 65-69, 70-77) were procured. The existing vehicles were also adapted to the new gauge . During the gauge changeover, the entry platforms of the wagons were lengthened , which inevitably led to an increase in mass. The performance of the older railcars was therefore no longer sufficient to carry a sidecar. The city arranged for eleven younger railcars to be equipped with a second traction motor, while eleven of the first series of railcars were converted into sidecars. At the same time, the railway increased the stock by purchasing 17 multiple units (No. 78-94) and eight sidecars (No. 30 II -37 II ). The city gave the oldest summer cars to the Kreuznach trams and suburban railways in 1907 .

In 1911, the municipal tram converted a further twelve railcars of the 40-63 series into sidecars and procured a further nine railcars (no. 108-116). The vehicles of the Spandau – Nonnendamm electric tram, acquired in 1910, were integrated into the numbering scheme when they were fully taken over by the municipal tram in 1914. At the beginning of the war, the Spandau municipal tram had 56 multiple units and 66 sidecars. As of August 1916, the sidecars were equipped with line signs like the railcars before.

In order to compensate for the longer maintenance periods on the vehicles due to the war, the railway rented sidecars 25 and 26 of the Woltersdorf tram in April 1917 for 100 marks per month. The Kaiserslautern tram was forced to sell three railcars (no. 117-119) with closed platforms, the engine power of which was strong enough to pull up to three sidecars. Four other railcars (no. 120–123) probably came from the Neunkirchen tram . In 1918, the Schwerin tram had to sell six motor coaches and six sidecars to Spandau, as the local armaments factories and Siemens factories continued to have a high number of passengers. With the exception of the Woltersdorfer sidecars, which returned in 1920, the purchased cars were taken over into the stock of the Berlin tram. The railcars were assigned the numbers 4126–4190, the sidecars the numbers 1480–1531.

- Vehicle overview

| Construction year | Track width (in mm) |

Car no. (Spandau) |

Number window |

Number Seating |

Manufacturer (mech.) |

Manufacturer (el.) |

Car no. (Berlin) |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horse-drawn carriage | ||||||||

| 1892 | 1000 | 1 + 2 | - | - | Couple, summer carriage ; Retired in 1894, in 1907 at Kreuznach Bw 13 + 14 | |||

| 1892 | 1000 | 3-6 | 4th | - | - | Single horse; Retired in 1897/99 | ||

| 1894 | 1000 | 7-13 | - | - | 1896 Car 7 retired, cars 8–13 converted to Bw; 1904 three Bw retired, 1907 three cars sold |

|||

| 1894-1895 | 1000 | 14-20 | 3 | 18th | - | - | 1896 conversion to Bw; 1904 Bw 20 decommissioned, in 1906 the rest of them in standard gauge |

|

| Railcar (Tw) | ||||||||

| 1896 | 1000 | 21-44 (40-63) |

5 | 16 | Van der Zypen & Charlier | 1533-1553 | Around 1904 renumbered to 40–63, 1906 to standard gauge; 1909/11 Tw 40–57 and 62–63 in Bw, 1920 to BSt Bw 1533–1553, retired in 1922; 1920 2 Tw in ATw 38 + 39, 1920 at BSt A16 + A17 |

|

| 1906 | 1435 | 65-69 | 3 | 18th | OK | AEG | 4126-4130 | 1924 Tw 4126-4129 retired; 1925/30 Tw 4130 in H12 |

| 1906-1908 | 1435 | 70-77 | 5 | 18th | Herbrand | AEG | 4131-4138 | Retired in 1925 |

| 1908-1909 | 1435 | 78-94 | 3 | 18th | Herbrand | AEG | 4139-4155 | 1925 Tw 4139-4141 retired; 1925 Tw 4142-4155 in Bw 1809-1822; Retired in 1929 |

| 1908-1909 | 1435 | 95-100 | 6th | 18th | AEG | 4156-4161 | 1914 ex Spandau – Nonnendamm Tw 1–6, retired in 1929 | |

| 1911 | 1435 | 101-107 | 3 | 18th | Van der Zypen & Charlier | AEG | 4162-4168 | 1914 ex Spandau – Nonnendamm, number 7–13, retired in 1929 |

| 1911 | 1435 | 108-116 | 6th | 18th | OK | AEG | 4169-4177 | retired by 1925 |

| 1914 | 1435 | 117-119 | 3 | 18th | Wismar | AEG | 4178-4180 | 1917 ex Kaiserslautern Tw 9–11, 1929 to ATw |

| 1435 | 120-123 | 3 | 18th | Van der Zypen & Charlier | AEG | 4181-4184 | 1917 presumably ex Neunkirchen Tw Series 1–11, withdrawn in 1923 | |

| 1435 | 124-129 | 18th | MAN | FFM | 4185-4190 | 1918 ex Schwerin Tw 1, 2, 13, 17, 20, 21, retired in 1923 | ||

| Sidecar (Bw) | ||||||||

| 1896 | 1000 | 1 II -7 II | 3 | 18th | Van der Zypen & Charlier | - | 1480-1486 | Standard gauge in 1906, retired in 1927 |

| 1909 | 1435 | 8 II -13 II | 8th | 24 | Falkenried | - | 1487-1492 | 1914 ex Spandau-Nonnendamm Bw 18-23, 1927 in 1471 II -1474 II and 1475 III -1476 III ; before 1949 Bw 1476 III retired; 1949 Bw 1471 II , 1475 III to BVG (West), retired in 1954; remaining 1949 to BVG (East), 1969 Reko |

| 1904 | 1000 | 20 II -29 II | 5 | 18th | - | 1499-1508 | Standard gauge in 1906, retired in 1927 | |

| 1909 | 1435 | 30 II -37 II | 3 | 18th | OK | - | 1509-1516 | the rest of them retired in 1925 |

| 1435 | 181-186 | 3 | 18th | HAWA | - | 1517-1522 | 1915 ex Schwerin Bw 35–42, 1926 Bw 1518 retired; others in 1926 in Bw 1584 II - 1587 II (meter gauge), retired in 1930 | |

| 1910-1911 | 1435 | 187-195 | 4th | 24 | OK | - | 1523-1531 | 1914 ex Spandau – Nonnendamm Bw 25–34; 1923 Bw 1523–1526 conversion for line 120 ; 1925 in Bw 1477 II -1485 II , 1946/48 Bw 1479 II +1480 II to Loren G337 + G338 (after KV); 1949 Bw 1477 II +1485 II to BVG (East), 1969 Reko; remaining 1949 to BVG (West), retired in 1954 |

| Work car | ||||||||

| 1435 | 38 II -39 II | 5 | A16-A17 | Work railcar | ||||

| 1435 | 196-198 | - | - | - | Salt car | |||

| 1435 | 199 | - | - | - | Explosive vehicle | |||

| 1435 | 204-205 | - | - | - | Track cart | |||

Depots

The first depot of the Spandau horse-drawn railway was located at Schönwalder Straße 43/44 in the former Grieftschen farmstead. The small wagon hall was given up in 1894 in favor of the new building on Pichelsdorfer Straße. The ruin of the wagon hall destroyed in World War II was torn down in 1958.

The second depot on Pichelsdorfer Strasse went into operation on June 24, 1894, after ADKA had taken over management. In 1895 a power station was built on the courtyard to provide electricity, in 1904 the wagon hall was expanded, a second hall was added in 1909 and a third hall in 1918/19. In the final stage there was space for a total of 103 cars. In 1920 he came to the Berlin tram as yard No. 28, from 1935 then under the abbreviation Spa . After the partial destruction in World War II, the BVG closed the courtyard on October 1, 1962. Today there are residential buildings on the site.

During the change of gauge from meter to standard gauge, a temporary hall for three wagons was built on the Schlangengraben for the trestle line, which had already been opened in standard gauge, through which the section from the plantation to the Spandauer Bock could be served. After the connection to the core network on July 20, 1907, the hall became dispensable.

In addition, the Grenzstraße depot in Siemensstadt existed for the Nonnendammbahn from 1909 . After the takeover of the Spandau – Nonnendamm tram, the hall was used to provide deployers. In 1944 the hall burned out. After the site had been cleared, BVG returned it to Siemens in 1950/51.

future

The first voices to reintroduce the tram in Spandau appeared after the fall of the Wall in the GDR . In 1994, the ProBahn passenger association published a brochure in which it was proven that operating a tram in Spandau as an island would cause ten percent more operating costs than bus operation, but double the number of passengers would be expected. In 2013 the “Spandauer Tram Initiative” (IST) was founded. This calls for the reintroduction of a separate Spandau tram network for the main corridors of the metro buses in Spandau (136/236, M37 and M49 as core network). The Berlin local transport plan 2019-2023 also provides for the construction of a tram network in Spandau for the period from 2029. Routes are planned in the area of Siemens- and Wasserstadt as well as from Spandau town hall to the residential area Heerstraße Nord and Falkenhagener Feld .

literature

- Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems at the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 30th year, 1981.

- Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . 8th year, no. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7-8, 10, 11, 12 , 1961.

- Wolfgang R. Reimann , Reinhard Schulz: Clues . VBN Verlag B. Neddermeyer, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-933254-68-X .

- Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d e Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 1 , 1961, pp. 1-2 .

- ^ A b Author collective: Tram Archive 5. Berlin and the surrounding area . transpress, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-344-00172-8 , pp. 177-178 .

- ↑ a b c Michael Kochems: trams and light rail in Germany. Volume 14: Berlin - Part 2. Tram, trolleybus . EK-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2013, ISBN 978-3-88255-395-6 , p. 130-136 .

- ↑ a b c Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems at the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 58-60 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 33-38 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 11-22 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 23-29 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 30 .

- ↑ a b c d Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 56-58 .

- ↑ a b Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 31-33 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 60-61 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 42-46 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 2 , 1961, p. 13-14 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 61-62 .

- ^ A b c Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 52-57 .

- ^ A b c Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 51 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 62-64 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 64-65 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 66-68 .

- ↑ a b c Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems at the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 68-69 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 57-63 .

- ↑ a b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 3 , 1961, pp. 16-17 .

- ↑ a b c d Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 64-67 .

- ↑ a b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 4 , 1961, pp. 24-25 .

- ↑ a b c d e Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 74-78 .

- ^ A b c Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 68-69 .

- ↑ a b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 6 , 1961, pp. 37-39 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 70-71 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 69 .

- ^ A b c d e Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 7-8 , 1961, pp. 49-51 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 80-89 .

- ↑ a b c Henry Alex: A century of local traffic in Haselhorst (part 1) . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 2 , 2010, p. 41-47 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 70-79 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 71-74 .

- ↑ a b c d Arne Hengsbach, Wolfgang Kramer: The trams in the Berlin area (12). Electric tram Spandau – Nonnendamm GmbH . In: Tram magazine . No. 48 , May 1983, pp. 127-134 .

- ↑ a b Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 80 .

- ↑ a b Arne Hengsbach: The tram of Siemens & Halske AG and Siemens-Schuckertwerke GmbH . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 8 , 1986, pp. 176-178 .

- ↑ Jens Dudczak, Uwe Dudczak: lanes in the Berlin area. Lehrter Bahn. In: berliner-bahnen.de. Retrieved October 29, 2018 .

- ^ A b c d e f Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 10 , 1961, pp. 68-71 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 91-98 .

- ^ A b c d e f Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 11 , 1961, pp. 77-80 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the electric trams in Berlin until 1945 . Berlin 1994, p. 276-277 .

- ↑ a b Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 101-104 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 105-108 .

- ↑ a b Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 109-110 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 110-118 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 119-128 .

- ^ Siegfried Münzinger: Tram route Spandau - Kladow . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 10 , 1962, pp. 83 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 159-184 .

- ^ Karl-Heinz Schreck: The tram of the community Heiligensee. 2nd part . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 6 , 1988, pp. 123-135 .

- ↑ a b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Spandau and his tram . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 12 , 1961, pp. 87-91 .

- ^ Author collective: Tram Archive 5. Berlin and the surrounding area . transpress, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-344-00172-8 , pp. 179-183 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 38-42 .

- ^ Arne Hengsbach: Spandau traffic problems around the turn of the century. Origin and development of the tram . In: Association for the history of Berlin (ed.): The bear from Berlin . 1981, p. 69-70 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Author collective: Tram archive 5. Berlin and surroundings . transpress, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-344-00172-8 , pp. 202-273 .

- ↑ a b The fleet of the “Berliner Straßenbahn” . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 11 , 1968, p. 152-162 .

- ^ Siegfried Münzinger: Tram profile. Episode 29 . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 4 , 1978, p. 77 .

- ^ Siegfried Münzinger: Tram profile. Episode 34 . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 11 , 1978, p. 213 .

- ↑ a b c d Siegfried Münzinger: The depots of the Berlin trams . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 8 , 1969, p. 141-147 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 245 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 245-247 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 247 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Kämpf: The tram in Spandau and around Spandau . Ed .: Heimatkundliche Vereinigung Spandau 1954 e. V. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938648-01-8 , pp. 248 .

- ^ Joachim Kochsiek: Berlin chooses trams . Verlag GVE, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-89218-028-8 , pp. 48 ff .

- ↑ Spandau wants its own tram network . In: BZ February 14, 2013 ( bz-berlin.de ).

- ^ Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection (ed.): Public transport requirement plan . Appendix 3 to the Berlin public transport plan 2019–2023. February 27, 2019, p. 6 ( berlin.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection (ed.): Nahverkehrsplan Berlin 2019-2023 . February 27, 2019, p. 238-239 ( berlin.de [PDF]).