Lower Rhine-Westphalian Imperial Circle

The Lower Rhine-Westphalian Circle (still called the Dutch -Westphalian Circle in the 16th century , later often just called the Westphalian Circle ) was one of the ten circles into which the Holy Roman Empire was divided under Emperor Maximilian I in 1500 and 1512 . The Westphalian Empire itself was established in 1500 and existed until the end of the Old Empire.

area

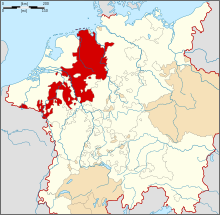

The district encompassed the territories between the Weser and the later border with the Netherlands to the Meuse and south to the Ahr and Sieg. To the right of the Weser were only the bishopric of Verden and the county of Schaumburg . However, within the boundaries of the district there were also areas that belonged to the Kurrheinische Kreis . This applies in particular to Kurköln with the associated parts Vest Recklinghausen and Duchy of Westphalia . In 1548, the bishopric of Utrecht and the duchy of Geldern were given to the Burgundian Empire by the Burgundian Treaty . The bishopric of Cambrai became French in 1678 and thus left the empire and the imperial circle.

organization

In 1512, the Reichskreis comprised a total of 55 district estates, whose representatives formed the district assemblies. These were rarely convened and then mostly took place in Cologne . The office and the district archive were located in Düsseldorf . In 1555 the Duke of Jülich-Kleve-Berg took over the district supreme office within the scope of the Reich Execution Code . The prince who wrote the district, later called the district director, was initially also the Duke of Jülich. The office passed to the Prince-Bishop of Münster at the beginning of the 17th century . After the Jülich-Klevischen succession dispute , the office was divided. In addition to Münster, the House of Pfalz-Neuburg (for Jülich) and Brandenburg (for Kleve) alternated.

The counts and lords of the region had been united in the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Imperial Count College since 1653 .

The Reichskreis had the right to present assessors for the Reichskammergericht . As a result of the religious division of the group, the Protestant and Catholic halves each provided two assessors in the 17th century.

history

The district estates pursued a more or less closed policy in 1534 to secure the peace in the fight against the Anabaptist Empire of Munster . From 1556 the district tried to standardize the coinage in connection with the imperial coinage system . Overall, the Reichskreis was most active in the 16th century when, among other things, it was necessary to raise the Turkish tax . In the following centuries the importance decreased.

The border situation with the Netherlands was problematic. The Eighty Years' War between the independence movement and Spain occasionally spread to areas in the imperial circle, for example in the Spanish winter of 1598/1599 . This is one of the reasons why the district sought armed neutrality during the Truchsessian War .

Foreign forces exerted a strong influence on the Reichskreis. Kurköln was a protective power of the north-west German Hochstifte . For a long time the House of Wittelsbach occupied important episcopal seats. Hesse, the Electoral Palatinate and the Guelph duchies continued to exert influence in the north. As a result of changes in ownership in some territories, with Braunschweig and Brandenburg, foreign rulers gained in importance from the end of the 16th century. In contrast, the Reichskreis remained largely remote from the emperor.

Denominational differences also intensified. In addition to Catholic areas, there were also Reformed and Lutheran territories. Various areas were disputed in the process of confessionalization . Overall, denominational differences and the different interests, especially the self-interests of the larger territories, made it difficult for the district to find a common line.

Foreign interests weakened the common coin policy. The non-armed district estates were disadvantaged by the existence of standing armies in the larger territories. The Lower Rhine-Westphalian Reichskreis is partly counted as part of the district association of the Frontier Reichskreis . This had formed against the expansion policy of Louis XIV . A district assembly held in Cologne in 1697 could not change that. After 1702, the district therefore only made about 2,000 men available for the Imperial Army . In the 18th century the district was mostly represented by the three directors and no longer played an independent role. District meetings were not held between 1738 and 1757. In 1789 the Reichskreis was given the task of executing the Reich against the Liège Revolution .

After all areas on the left bank of the Rhine were ceded to France , the Reichskreis was dissolved in 1806.

Members

The following are the members of the imperial circle are listed, starting from the Reichsmatrikel the year 1521 and a collection of 1532. Until Outbound towards the end of the empire imperial estates are in italics printed, newly added listed separately.

Spiritual princes

Dioceses

-

Bishopric Cambrai ; 1678 French

-

Liège Monastery

Liège Monastery

-

Hochstift Minden ; 1648 secular principality

-

Monastery of Münster

-

Osnabrück Monastery

-

Paderborn Monastery

Paderborn Monastery

-

Utrecht Monastery ; 1528 to Spain , 1548 to the Burgundian Empire , later Dutch

-

Bishopric Verden ; 1648 secular principality

Abbeys

-

Stablo-Malmedy Abbey ; before prelature

Stablo-Malmedy Abbey ; before prelature -

Corvey pen ; before prelature; 1792 Hochstift

Secular princes

-

Duchy of Jülich-Berg with the county of Ravensberg , from 1521 to 1609 personal union as United Duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg , 1614 provisional and 1666 final division between the margraviate of Brandenburg and Pfalz-Neuburg .

-

Duchy of Kleve with the county of Mark , from 1521 to 1609 personal union as united duchies, 1614 provisional and 1666 final division of inheritance between the margraviate of Brandenburg and Pfalz-Neuburg .

-

Duchy of Geldern ; 1538 to House Mark in personal union as United Duchies, from 1543 through military intervention of the Emperor to Habsburg , 1548 to the Burgundian Empire

Duchy of Geldern ; 1538 to House Mark in personal union as United Duchies, from 1543 through military intervention of the Emperor to Habsburg , 1548 to the Burgundian Empire

until 1792 new:

-

Principality of Minden ; from 1648, previously a clerical principality

-

Principality of Verden ; from 1648, previously a clerical principality

-

Principality of Nassau-Dillenburg ; Princely in 1664, previously an imperial county

Principality of Nassau-Dillenburg ; Princely in 1664, previously an imperial county -

Principality of East Frisia ; Princely in 1667, previously an imperial county

Principality of East Frisia ; Princely in 1667, previously an imperial county -

Principality of Moers ; 1706 principality, previously a county; without imperial estate

Principality of Moers ; 1706 principality, previously a county; without imperial estate

Imperial prelates

-

Corvey Abbey ; no later than 1582 prince abbey, 1792 Hochstift

-

Kornelimünster Imperial Abbey

Kornelimünster Imperial Abbey

-

Stablo-Malmedy Abbey

Stablo-Malmedy Abbey

-

Become an abbey

Become an abbey

-

Frauenstift Essen

Frauenstift Essen

-

Herford women's monastery

-

Thorn Women's Foundation

Thorn Women's Foundation

-

Echternach Monastery

Echternach Monastery

Counts and gentlemen

-

County of Bentheim

County of Bentheim

-

County of Manderscheid ; 1,546 of Habsburg mediated

County of Manderscheid ; 1,546 of Habsburg mediated

-

County of Bronkhorst ; Extinguished in 1719

County of Bronkhorst ; Extinguished in 1719 -

County of Diepholz

-

County Hoya

-

County Lippe

County Lippe

-

County of Moers ; 1541 Kleve mediated , 1706 Principality; without imperial estate

County of Moers ; 1541 Kleve mediated , 1706 Principality; without imperial estate -

Nassau-Dillenburg county ; 1664 principality

Nassau-Dillenburg county ; 1664 principality -

County of Oldenburg , 1777 duchy

County of Oldenburg , 1777 duchy -

County of East Friesland ; 1667 principality

-

Pyrmont county

-

Reichenstein reign

Reichenstein reign

-

County of Rietberg

County of Rietberg

-

County of Salm-Reifferscheid

-

County Sayn

-

Schaumburg County

-

Spiegelberg county

-

Steinfurt County

-

County of Tecklenburg

-

Virneburg county

-

County of Wied

-

Lordship of Winneburg and Beilstein

Lordship of Winneburg and Beilstein

-

Reckheim lordship, owned by the von Sombreffe lords, after 1623 Reckheim county

Reckheim lordship, owned by the von Sombreffe lords, after 1623 Reckheim county

until 1792 new:

-

Herrschaft Anholt (represented by the Prince of Salm-Salm )

-

County of Blankenheim and Gerolstein

County of Blankenheim and Gerolstein

-

Dominion Gemen

Dominion Gemen

-

Reign of Gimborn

Reign of Gimborn

-

Gronsveld county

-

County of Hallermund

County of Hallermund

-

County of Holzappel

County of Holzappel

-

County of Kerpen and Lommersum (1786 immediately imperial)

County of Kerpen and Lommersum (1786 immediately imperial) -

Myllendonk reign

Myllendonk reign

-

County of Reckheim (1620 immediately imperial)

County of Reckheim (1620 immediately imperial) -

Grafschaft Schleiden (end of the 16th century immediately under the Empire)

Grafschaft Schleiden (end of the 16th century immediately under the Empire) -

Reign of Wickrath

Reign of Wickrath

-

Reign of Wittem

Reign of Wittem

counties belonging to district without imperial estate:

-

County of Lingen

-

Grafschaft Ravensberg from 1346 personal union with the Duchy of Berg , 1437 with Jülich-Berg and from 1521–1609 part of the United Duchies, 1614 provisionally and 1666 permanently to the Margraviate of Brandenburg .

Grafschaft Ravensberg from 1346 personal union with the Duchy of Berg , 1437 with Jülich-Berg and from 1521–1609 part of the United Duchies, 1614 provisionally and 1666 permanently to the Margraviate of Brandenburg . -

since 1614: County of Hoorn

since 1614: County of Hoorn

Cities

Imperial cities:

Imperial immediacy controversial:

-

Duisburg (represented by Kleve - Mark )

Duisburg (represented by Kleve - Mark ) -

Herford (represented by Jülich-Berg )

Herford (represented by Jülich-Berg ) -

Verden (represented by Jülich-Berg )

Verden (represented by Jülich-Berg )

No imperial estates:

-

Brakel (represented by Paderborn )

Brakel (represented by Paderborn ) -

Düren (represented by Jülich-Berg )

-

Lemgo (represented by Grafschaft Lippe )

Lemgo (represented by Grafschaft Lippe ) -

Soest (represented by Kleve - Mark )

Soest (represented by Kleve - Mark ) -

Warburg (represented by Paderborn )

Warburg (represented by Paderborn ) -

Wesel (represented by Kleve - Mark )

Wesel (represented by Kleve - Mark )

Enclaves

Territories that did not belong to the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire and were wholly or partially enclosed by the district:

-

Kurköln with the Duchy of Westphalia and Vest Recklinghausen ; Kurheinischer Reichskreis

Kurköln with the Duchy of Westphalia and Vest Recklinghausen ; Kurheinischer Reichskreis

-

Duchy of Limburg ; Burgundian Empire

Duchy of Limburg ; Burgundian Empire

-

Imperial Abbey of Burtscheid ; circular

Imperial Abbey of Burtscheid ; circular -

Imperial rule Dyck ; circular

Imperial rule Dyck ; circular -

Rule Hörstgen ; Imperial immediacy controversial, independent

Rule Hörstgen ; Imperial immediacy controversial, independent -

Reign of Rheda ; no imperial class, independent of a circle

-

Imperial rule Saffenburg , independent

Imperial rule Saffenburg , independent

See also

literature

- Winfried Dotzauer: The German Imperial Circles (1383-1806) . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07146-6 ( online at google books ). P. 297ff.

- Andreas Schneider: The Lower Rhine-Westphalian district in the 16th century . History, structure and function of a constitutional body of the old empire. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1985, ISBN 3-590-18128-1 (Düsseldorfer Schriften zur Neueren Landesgeschichte and the history of North Rhine-Westphalia, Volume 16).

- New European state and travel geography in which the lands of the Westphalian district are presented in detail ... (= 8th volume of the complete work), Dresden / Leipzig (no year, 1757)

- Gerhard Taddey (ed.): Lexicon of German history . People, events, institutions. From the turn of the times to the end of the 2nd World War. 2nd, revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-520-81302-5 , pp. 879f.

Web links

- Publications on the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire in the catalog of the German National Library

- Search for Niederrheinisch-Westfälischer Reichskreis in the German Digital Library

- Search for Niederrheinisch-Westfälischer Reichskreis in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Overview of the imperial estates

- Niederrheinisch-Westfälischer Reichskreis in the portal Rheinische Geschichte of the Rhineland Regional Association

- Illustration by Nicolaes Visscher I approx. 1678: 'S [acri] R [omani] I [mperii] Westphaliae Circulus: In Omnes Eiusdem Subiacentes Provincias exactißimè distinctus' ( digital copy )

- Map from 1627 demolition of the Valtellina landscape, removed from the Spanish by the French General Marquis Di Covure ( digital copy )

- Map from 1627 Outline of the Westpalen, Frieslandt und Angrenden Landeren landscape ( digitized version )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Winfried Dotzauer: The German Imperial Circles (1383-1806) . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07146-6 , chapter Niederrheinisch-Westfälischer Kreis, p. 297–333 ( online at google books ).

- ^ Klaus Müller: Under Palatinate-Neuburgian and Palatinate-Bavarian rule. In: Hugo Weidenhaupt: Düsseldorf. History from the origins to the 20th century. Schwann in Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-491-34222-8 , Volume 2, p. 29

- ↑ Sigrid Jahns : The Reich Chamber of Commerce and its judges. Constitution and social structure of a highest court in the old empire Part I: Presentation. Cologne, 2011 p. 253