Money jew

One of the stereotypes about Jews is that of the money Jews , the usury Jews , or the Jewish money lenders, all of them ethnophaulisms . The myth of “Jewish financial rule” developed from the associated prejudice of a special Jewish affinity for money . The stereotype became the "capital of the American east coast " as well as domination of the media, the world economy and world politics. All of this is rooted in the idea of the medieval moneylender as a usurer who is said to have harmed the Christian population and who then became the influential banker of modern times who manipulated financial transactions on the stock exchange .

etymology

The perception of Jews as "money Jews" is shaped by the widespread cliché of "usury", which was originally just the German word for interest derived from the Latin census (= estimation) . The concept of usury comes from the Germanic root wokaraz ; From Middle High German wuocher , Old High German wuochar , for offspring, (interest) profit, increase or increase. Much later, the meaning developed from this in the sense of the far excessive interest when lending money or the achievement of a disproportionately high profit when selling goods. In Martin Luther's translation of the Bible ( Luther Bible ) of September 1522, the terms “interest” and “usury” are still equated. The “ Judenzins ” became an anti-Judaistic term for usury or usury in the 18th and 19th centuries . The money Jew became a synonym for usurers, the money Jewry became a synonym for "Jewish usury". Variants of the term can be found in "Bank Jews", "Coin Jews", "Schacher Jews", "Trade Jews" or "Finance Jews", through to "Korn Jews".

History of origin

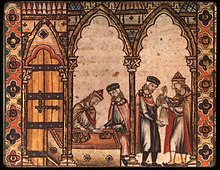

From Judas Iscariot , who betrayed the Lord for thirty pieces of silver, to the figure of Shylock to the Rothschilds, hardly any stereotype in the history of the Christian West is as virulent as that of the greedy Jew. For a long time, historians believed that Jews dominated money lending in the Middle Ages because Christians were forbidden to take interest. Complaints or even outrage about Jewish moneylenders would have been common. However, this view is not correct. Indeed, the interest prohibition aimed at manifestations within Christianity . Bernhard von Clairvaux (1090–1153), for example, described the Christian moneylenders as even worse than the Jewish in a letter addressed to the clergy and the people in Eastern Franconia and Bavaria. To do this, he used the Latin neologism judaizare , a pejorative term intended to denote “normal Jewish behavior”, for lending money against interest .

- In 1139 in the Second Lateran Council 13 archbishops, bishops and abbots of any order were forbidden from collecting interest.

- In 1179 in the Third Lateran Council in Canon 25, the increasingly widespread crime of taking interest (“as if they were allowed to practice it”) was forbidden as a punishment of excommunication. Clergymen who allowed usury were to be suspended immediately.

- In 1215, in the Fourth Lateran Council, 67 Jews were banned from "severe and excessive usury [...] with which they exhaust the wealth of Christians in a short time".

Accordingly, the “heavy and excessive usury” - thus the “heavy and excessive interest” - was prohibited, not the “usual usury” - the “usual interest”.

In a short article in the Handbuch des Antisemitismus, Clemens Escher describes the situation in a very abbreviated form, describing the Jews' money lending as their monopoly , which on the one hand is not true and at the same time does not mean that all Jews only lived from money lending.

“Since the rigorous prohibition of usury of the church did not apply to the Jews who had been socially excluded since the fourth Lateran Council in 1215, it was they who took on the ostracized and indispensable profession of moneylender. They now granted the credit without which the economy could no longer function since the High Middle Ages. A monopoly that the Jews were only allowed to exercise against high taxes, compulsory loans and protection money to kings, cities and princes. "

The stereotype of Jewish usury is rarely found in German popular sermons or other German texts after the 12th century. The only sources for this connection are the chronicles of the German cities. The aim of the ecclesiastical preachers' agitation against usury was mainly the Christian usurer. The combination of money lending by Jews with the alleged desecration of the host , on the other hand, became a strategy against a conspiratorial realization of the Jewish striving for power and a religious defamation.

In the 14th century, only money dealers (and doctors) could acquire a residence permit in German cities, other professions were only pursued as secondary to the credit business. Individual money dealers working on their own account, with their own capital and at their own risk appear to be typical of the organizational forms of money lending. However, he often socialized with other Jews in order to carry out larger business and to protect himself against dubious risks - especially with foreign customers. “The topos of the Jew as a usurer who brings the people into their“ interest bondage ”appeared early on and was one of the most important components of the anti-Jewish stereotype. In the eyes of the majority, he gave the minority an almost uncanny power. In the late Middle Ages, the authorities adopted such ideas and became increasingly unwilling to use the judicial apparatus for the benefit of Jewish creditors, ”said historian Michael Toch .

Crusaders who had taken out loans were absolved of their oath to pay the usury, and their creditors were ordered to refund the interest. Jews were to be compelled by secular power to remit interest and until then be banned from fellowship with Christians. For the repayment of the actual debt, the crusaders should be granted preferential conditions.

Until the 19th century it was part of the policy of many sovereigns to see the Jews as useful money collectors. They were commissioners of the authorities, and although they collected taxes from the people, they in turn had to pay enormous sums of money to the sovereigns and the emperor. So the cliché of the greedy interest-taker and usurer used for the tax collector did not stick to the real recipients of the money, the sovereign princes, but to their intermediaries, the Jews.

Bogus causality

As an attempt to explain a prevalence of Jews in the monetary system, it is stated that they were prohibited from most activities in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, among other things because they were not allowed to become members of a guild or merchant's guild , and they were also prohibited from acquiring land - Measures to keep unpleasant competition at bay. So they had no choice but to concentrate on the money business, which Christians are said to have been forbidden. Like no other economic activity of the Jews in the Middle Ages, the Jewish money and credit business exacerbated existing prejudices and resentments and contributed to the creation of anti-Jewish stereotypes, some of which continue to have an impact today. The money business was by no means the only livelihood of the Jews in medieval Ashkenaz , but it was a particular focus of Christian attention. In the craft sector, the dividing line between Western and Eastern Europe was particularly evident. While only a few Jewish craftsmen worked in Western Europe, where the guilds had excluded Jews for centuries, there were numerous Jewish tailors and shoemakers, bakers and goldsmiths in Eastern Europe.

The economic importance of the Jewish minority in the newly emerging cities at the end of the 12th and 13th centuries in a new role - be it as traders, money and pawnbrokers or administrators of mints had two consequences. On the one hand it covered the need for money for the growing economy despite the interest ban, on the other hand it could be discriminated and persecuted as a scapegoat. Those who couldn't get a loan anywhere could borrow money from Jews for interest. The connotation of “Jewish money” and the stereotypical image of the greedy and deceitful “Jewish usurer” have their origin here and, in the course of centuries of cultural practice, have shaped a whole complex of myths that continues to affect the present. The profession of moneylender was decried as immoral, Jews were portrayed as greedy, stingy and unscrupulous. This intensified with the rise of the mendicant orders and the poverty movement in the late Middle Ages. Absurd extrapolations were imputed to the Jews, such as, for example, the lending of a guilder through compound interest effects would result in astronomical debts extrapolated over 20 years.

The cleric Madison Clinton Peters (1859–1918) tried to debunk the myth as early as 1899. However, the view of the medieval history of the Jews in Germany only started to move in the 1990s and gained new perspectives, including the myth of the “rich Jew”. Contrary to popular belief, the Christian prohibition of interest was little respected in reality. The canonical legislation has been and is equated with the legal reality incorrectly. Church law was not a secular law. From 1179 the church could only threaten the usurers by refusing a Christian burial, failing confession and the Lord's Supper , or from 1274 with excommunication during their lifetime. Both exclusively concerned Christians. Ultimately, however, it remained with the threats.

On the other hand, the guilds and guilds were limited to the cities, so that Jews in rural areas could very well be active in many craft trades . Craft and other activities of all kinds within the Jewish communities were also vitally necessary, such as tailors , shoemakers , blacksmiths , weavers , bakers , doctors , carpenters , farmers , traders or various ritual activities such as rabbis , butcher , mohel and others. There were also trades that were despised by society in the Middle Ages, including millers , shepherds , skinners , tanners , bathers and barbers . For centuries, these crafts were classified as dishonest professions - in the sense of dishonorable professions - and were therefore not barred to Jews.

The vast majority of the Jewish population lived in poor conditions so that they did not have the means to act as moneylenders. Jewish money lending differed in some respects from Christian money. Until the first public pawn shops appeared in Italy in the 15th century, the Jews had the privilege of pawnbrokers . This made the Jews into lenders of "little people", the bourgeoisie, artisans and farmers. But there were undoubtedly a few wealthy Jews who - alongside the much more numerous Christian moneylenders - were active, which, however, does not allow any reference to Jews or a generalization. For example, consider the Fugger , the Medici , the Tuscans who Kawerschen or Lombards , many citizens of Asti and Arras , the Pepoli (especially Romeo Pepoli , Taddeo Pepoli ) or in England Audleys and Caursinis pointed out. In the Middle Ages, the Franciscan Order established the first pawn shops in Italy, the so-called Monte di Pietà , which only demanded "cost-covering" interest from the borrowers, around 10%. The Friars Minor in their sermons lamenting the alleged usury of the Jews and thus provoked riots over again. The controversial anti-Jewish topics such as the "usury of the Jews", the " sacrifice of the host " and the " ritual murder " made the Minorite Johannes Capistranus (1386–1456) the central points of his sermons, which in 1453 led to one of the worst auto-dafe of this time in Breslau .

The historian Michael Toch emphasized in his article Die Juden im Mittelalterlichen Reich ( The Jews in the Middle Ages) that, contrary to popular beliefs, life in Europe in general and in Germany in particular represents only one and by no means the most important section of Jewish history in the Middle Ages. The Judaism of Central Europe could not compete with the Babylonian Judaism of the early Middle Ages or the Iberian Judaism under Islamic and later Christian rule neither in population nor in its intellectual and social achievements. He states “that modern research has dispelled the notion that Jews devoted themselves exclusively to the credit and moneylending professions. Rather, it was found that a significant part of the population found their livelihood in service occupations for the upper class of traders and moneylenders, also that towards the end of the late Middle Ages a renewed tendency to trade in goods is noticeable. "..." The earlier view that the reasons for the persecutions at found the Jews themselves, especially in their economic behavior as moneylenders or merchants with monopoly control of trade, is wrong according to today's understanding. Rather, more recent research agrees that the driving forces are to be sought in the profound religious changes in Christian society, which can be described with the key words Eucharistic piety, poverty movement, church reform, end-time expectation, developed in the course of the 11th century and in the Crusade movement culminated. "

Consolidation of prejudice

Well-known historical figures consolidated the anti-Semitic prejudice that money was in the hands of Jews. In 1858, for example, the French early socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon attributed a “mercantile and usurious parasitism ” to the Jews and declared the Jewish parasite .

For Alphonse Toussenel (1803–1885) “Jew, usurer and money dealer” were synonyms ( French “Juif, usurier, trafiquant sont pour moi synonymes” ). The American poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972) polemicized in several of his Cantos , published in 1937, against Usura ( Latin for usury), which he viewed as “cancer damage to the world” and described as typically Jewish.

This image penetrated deeply into people's consciousness through legends and sagas , folk novels and caricatures and found a prominent embodiment in William Shakespeare's Shylock in the Merchant of Venice in 1600 . When Shakespeare wrote this play, there were no Jews in England. They had already been expelled in 1290. His moneylender Shylock was already the product of a traditional obsession rather than a real observation.

In the court of the 16th century played a few hundred from the end by the end of the 18th century Europe as Court Jews known Court Jews a solid financial economic role. The court factor was a merchant employed at a courtly rulership center or in the court who was (luxury), procured army supplies or capital for the ruler.

The figure of Joseph Suess Oppenheimer , one of the most famous examples of a court factor who was executed in Stuttgart in 1738 after the sudden death of his sovereign and patron, Duke Karl Alexander (1684–1737) because of his (supposedly) Jewish “ cabal ”, solidified the prejudice : In 1827 Wilhelm Hauff published his novella Jud Suss , in 1925 the novel of the same name by Lion Feuchtwanger appeared , in 1930 Paul Kornfeld brought out a play Jud Suss , in 1934 the film Jud Suss by Lothar Mendes was released in British cinemas, in 1940 Veit Harlan brought out the National Socialist propaganda film Jud sweet out.

The numerous members of the Rothschild or Warburg banking families are considered prototypical “money Jews” .

Conspiracy theories arose, such as in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion published at the beginning of the 20th century , which are still at work today. In his horror novel "Biarritz" (a source of the "Protocols of the Elders of Zion"), Hermann Goedsche, alias Sir John Retcliffe , described the alleged banking and stock exchange actions of the Jews who were supposed to use money as a weapon as early as 1868. In his book The Conspiracy - The True Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Will Eisner has exposed the baiting of Jews and linked it with the wish that his work "may perhaps drive another nail into the coffin of this terrible, vampire-like fraud".

The defamation of allegedly Jewish business methods also took up relatively large space in the “Handbuch der Judenfrage”, first published in 1907. In 1913, the author Theodor Fritsch published under a pseudonym an extensive and outrageous treatise on "Jews in trade and the secret of their success". This also includes the pamphlet by Henry Ford , published in 1920–1922, entitled “ The International Jew ”.

The historian Wolfgang Geiger criticizes that the prejudice has persisted to this day in the history books of high schools and even in the Brockhaus encyclopedia from 2004 or the Duden student dictionary . While considerable progress has been made in the field of German-Jewish history in the field of science thanks to new chairs, institutes and extensive research, this does not apply to the same extent to the school sector.

Abraham Foxman describes six facets of prejudice against Jews that constitute “economic anti-Semitism”. They have persisted to this day and can be found around the world, particularly in the UK, Germany, Argentina and Spain:

- All Jews would be rich.

- Jews would be stingy and greedy.

- Powerful Jews would control the business world.

- Judaism would focus on profit and materialism.

- Jews would be allowed to cheat non-Jews.

- Jews would use their power to benefit "their own species".

The political scientists Marc Grimm and Bodo Kahmann write: “In the stereotype of the money Jew, the impersonal power medium of money is personalized, substantiated and concretized, and abstract, anonymous power relationships are thus translated back into personal ones. There is a resubstantialization of the abstract power medium money in the figure of the money Jew. This mechanism shows the inability of anti-Semites to deal with abstract forms of property, it shows their turn to pre-capitalist forms of accumulation and a mythical relationship to property that is imagined as rooted in the national community. The civilizational development step from real estate to free-floating capital, finance capital, is not carried out in anti-Semitism ”.

Jean-Paul Sartre countered what he believed to be a false and dangerous interpretation of this form of anti-Semitism: 'So apparently the idea one makes of the Jew determines the story and not the historical event that determines the idea. "In historical research on anti-Semitism it is According to the sociologist and anti-Semitism researcher Klaus Holz in 2001, “that modern anti-Semitism cannot be explained by conflicts about material resources between the Jewish and non-Jewish population is now undisputed . A closeness of the Jews to capitalism is stated, but no “correspondence-theoretical explanation” is derived from it; It is clear that the “special characteristics of Jewry” play the role of, and this is central, only “apparent evidence of anti-Semitic prejudices”. And yet the famous "grain of truth" that seems to be found so quickly in the stereotype still haunts scientists, more or less explicitly, through the heads and also through the texts of scientists. The historical event is analyzed and described again and again with the help of long-known, often astonishingly stereotypical "images of the Jews". Certain ideas and descriptions of the "economic situation" of the Jews, of the driving force behind the development of the Jewish economy and of the "lively" characteristics of "the Jews" in the economy seem to be so plausible that they could hold up over time . "

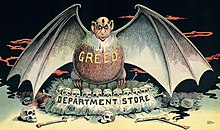

Establishment up to the modern age

The medieval stereotypes of “Jews and money” persisted into the 21st century. Over the centuries the theme has been translated into "Jews as enemies of Christianity and humanity", "Jews and the Antichrist" and "Jews and world domination" through various types of visualizations. These tropes are carried over into the secularized and "thoroughly capitalized" world of today. According to the Germanist and anti-Semitism researcher Winfried Frey , they are passed on from generation to generation and still affect various forms of discourse, from political agitation and caricature to children's books. The ordinance issued by the National Socialists in 1938 to exclude Jews from German economic life strengthened the medieval image of the “money Jew”.

In his 1911 published work Die Juden und das Wirtschaftsleben , the sociologist and economist Werner Sombart (1863–1941) made the Jews responsible for the establishment of capitalism . The anti-Semitic stereotype that has influenced European economic theory and practice since the early medieval ban on usury stigmatized the Jewish people as having played a special role in the economy. Sombart not only marked the special ability of the Jews for the capitalist economic system, but also assigned the court Jews in particular a decisive share in the establishment and development of the modern state. This share is based on the performance of the court Jews as suppliers and financiers. Sombart is one of the German intellectuals who underpinned such centuries-old stereotypes with pseudo-scientific arguments that gave anti-Semitism its particularly brutal power in the first half of the 20th century. For the scientist Friedemann Schmoll , Sombart thus built a bridge to open anti - Semitic anti - capitalism . There is also no mention of “money Americans”, “money Arabs”, “money Chinese” or “money Russians”, although there are numerically far more wealthy people who play an important role in the world economy.

The historian Hannah Ahlheim writes that “the specifically modern anti-Semitic thinking and the images of the 'economic Jew' are indeed based on 'real' social and economic structures that governed society and the economic order of the late 19th and 20th centuries and thus also shaped the living environment and the inner world of the anti-Semites. But it is precisely this inner world, it is the inner conflicts, the desires, fears and aggressions, it is the fantasies of the anti-Semites that confront us in the form of 'the Jew' that they "look into" the abstract figure of the Jew. and seem to be able to prove it on concrete people and structures. "

See also

literature

- Gunnar Mikosch: Of Jewish usurers and Christian preachers. A search for clues. In: Ashkenaz. 20, 2012, doi : 10.1515 / asch-2010-0018 .

- Julie L. Mell, The Myth of the Medieval Jewish Money Lender , ( english The myth of the medieval Jewish moneylender ), Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, Volume I ISBN 978-1-137-39776-8 and 2018, Volume II, 2018, ISBN 978 -3-319-34185-9 ,

- Winfried Frey : The "usury Jew" as a caricature of Christian practice . In: Das Mittelalter 10 (2005), Issue 2, pp. 126-135 ( online ).

- Peter Waldbauer: Lexicon of anti-Semitic clichés: anti-Jewish prejudices and their historical origins . Mankau Verlag GmbH, 2007, ISBN 978-3-938396-07-0 .

- Wolfgang Geiger, Christians, Jews and Money - On the permanence of prejudice and its roots , In: Insight 04. Bulletin of the Fritz Bauer Institute, autumn 2010, pp. 30–37. online: Between judgment and prejudice: Jewish and German history in collective memory 2012, ISBN 978-3-941743-23-6 , pp. 105–118.

Web links

- The enemy image of the “Jewish usurer” , building block for non-racist educational work, DGB-Bildungswerk Thuringia. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

Individual evidence

- ^ Editorial , Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation Rhein-Neckar, March 2019. Retrieved on August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Money In: Jewish History. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ↑ Wolfgang Geiger, "Money Lenders" versus "Bankers" - The Origin of Money Transactions and their Carriers. Cliché and Reality of the Middle Ages , AG German-Jewish History in the Association of German History Teachers. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Usury , Duden. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Geldjuderei , Campe, M. Kramer 1787, in: German dictionary by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. 16 vols. In 32 partial volumes. Leipzig 1854–1961.

- ↑ Manfred Gailus, The Invention of the "Korn Jew". On the history of an anti-Jewish enemy image of the 18th and early 19th centuries , in: Historische Zeitschrift 272 (2001), 3, pp. 597–622.

- ^ Sara Lipton: Dark Mirror. The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography . Metropolitan Books, 2014, ISBN 978-0-8050-7910-4 , pp. 171-199.

- ↑ Kurt Schubert: Jewish history . CH Beck, November 20, 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-64366-8 , p. 47.

- ↑ Clemens Escher: Usury Jew. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus . Volume 3: Concepts, ideologies, theories. De Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-24074-4 , pp. 348-349. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Johannes Heil, Conspiracy, Usury and Enmity against Jews or: the calculation of the Antichrist - a sketch. Dedicated to Wolfgang Benz on the occasion of his seventieth birthday , Aschkenas , Volume 20, Issue 2, 2012, De Gruyter

- ↑ Michael Toch, The Jews in the Middle Ages , Series: Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte, 44, De Gruyter, 2014. ISBN 978-3-486-56711-3 , pp. 39-40. ( Online )

- ^ Peter Waldbauer: Lexicon of anti-Semitic clichés: anti-Jewish prejudices and their historical origins . Mankau Verlag GmbH, 2007, ISBN 978-3-938396-07-0 , p. 83.

- ↑ Craftsman , Judengasse.de. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Michael Brenner: A Little Jewish Story . CH Beck, 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-62124-6 . , P. 267.

- ↑ Wolfgang Geiger, moneylender "against" Bankers - the emergence of money transactions and their carriers. Cliché and Reality of the Middle Ages , AG German-Jewish History in the Association of German History Teachers. P. 11.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Antisemitism. Presence and tradition of resentment. Wochenschau Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-7344-0104-6 , SS 18ff. u. 29ff.

- ↑ Madison Peters, Chapter 9: The Jew in finance in: Justice To The Jew: The Story Of What He Has Done For The World (English), The Baker and Taylor, New York, 1899, pp. 203-234

- ↑ Michael Toch, Wilfried Feldenkirchen: The Jews in the medieval empire . Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 1998, ISBN 978-3-486-55053-5 . , P. 85.

- ↑ Wolfgang Geiger, "Money Lenders" versus "Bankers" - The Origin of Money Transactions and their Carriers. Cliché and Reality of the Middle Ages , AG German-Jewish History in the Association of German History Teachers. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Jost Schneider: Social history of reading. On the historical development and social differentiation of literary communication in Germany . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-017816-8 , p. 154.

- ^ Occupational fields of the Jewish population in the Middle Ages , Institute for Historical Regional Studies at the University of Mainz. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ↑ Horst Fuhrmann: The Middle Ages are everywhere: from the present of a past time . CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60487-4 , p. 140.

- ^ About the usury of Jewish and Christian moneylenders , Jüdisch Historischer Verein Augsburg. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ↑ Kawerze , German legal dictionary. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Robert Henry: The History of Great Britain 1788, p. 282.

- ↑ Madison Peters, Chapter 9: The Jew in finance in: Justice To The Jew: The Story Of What He Has Done For The World , The Baker and Taylor, New York, 1899, p. 230.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Gilomen, Usury and Economy in the Middle Ages, Historical Journal, Volume 250, Oldenburg Verlag 1990. P. 274.

- ↑ J. Mees: Montes. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 6, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-7608-8906-9 , column 796 f.

- ↑ Arno Herzig: Jewish history in Germany: from the beginnings to the present . CH Beck, 2002, ISBN 978-3-406-47637-2 . P. 63

- ↑ Michael Toch, The Jews in the Middle Ages , Series: Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte, 44, De Gruyter, 2014. ISBN 978-3-486-56711-3 , p. 96 and p. 112. ( online )

- ↑ Paul Assall, Jews in Alsace , Elster Publishing Moos, 1984, ISBN 3-89151-000-4 , p 88th

- ↑ Alexander Bein : The Jewish Parasite. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 13, Issue 2, 1965, p. 128. ( online . Accessed August 12, 2020)

- ↑ Micha Brumlik : Anti-Semitism in early socialism and anarchism . In: Ludger Heid and Arnold Paucker (eds.): Jews and German workers' movement until 1933. Social utopias and religious-cultural traditions . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1992, p. 38.

- ↑ Hans-Christian Kirsch : Ezra Pound with self-testimonies and picture documents. rororo, Reinbek 1992, p. 92.

- ↑ Julia König: Anti-Semitism from Antiquity to Modern Times , Federal Center for Political Education, November 23, 2006. Retrieved on August 12, 2020.

- ↑ Dan Diner: Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture: Volume 3: He – Lu . Springer-Verlag, September 6, 2016, ISBN 978-3-476-01218-0 , pp. 84-88.

- ↑ Will Eisner , The Conspiracy - The True History of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, German Publishing House, Munich, 2005, ISBN 3-421-05893-8

- ^ German-Jewish history in the classroom - an orientation aid for schools and adult education , commission of the Leo Baeck Institute for the dissemination of German-Jewish history. 2nd edition 2006. Accessed August 15, 2020.

- ^ Abraham H. Foxman: Jews and Money: The Story of a Stereotype . St. Martin's Publishing Group, November 9, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-11225-4 . (English)

- ↑ Foxman p. 84

- ^ Foxman p. 89

- ^ Foxman p. 93

- ↑ Foxman p. 98

- ^ Foxman p. 102

- ^ Foxman p. 105

- ↑ Marc Grimm, Bodo Kahmann: Anti-Semitism in the 21st Century: Virulence of an Old Enmity in Times of Islamism and Terror . De Gruyter, October 8, 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-053709-3 , pp. 76–79.

- ^ Jean Paul Sartre, Reflections on the Jewish Question. Psychoanalysis of anti-Semitism , (Original title: Reflexions sur la question juive ), Europa Verlag, Zurich, 1948, ISBN 978-3-499-13149-3 , pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Klaus Holz, Nationaler Antisemitismus - Wissenssoziologie einer Weltanschauung , Hamburger Edition, 2010, ISBN 3-86854-226-4 , p. 7.

- ↑ Winfried Frey: The Jews know no pity. They only strive for one thing, money. Medieval stereotypes of the usury Jews in German texts from the early modern period to the 20th century. In: Ashkenaz. 20, 2012, De Gruyter, doi : 10.1515 / asch-2010-0021 .

- ↑ The Jews and Economic Life , Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig (archive.org)

- ↑ Ulla Kypta, Julia Bruch, Tanja Skambraks, Grand Narratives in Premodern Economic History , in: Methods in Premodern Economic History - Case studies from the Holy Roman Empire, 1300–1600. (English) Springer, 2019, ISBN 978-3-030-14659-7 . P. 25.

- ↑ Friedemann Schmoll: The defense of organic orders: nature conservation and anti-Semitism between the German Empire and National Socialism. In: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter: Nature conservation and National Socialism. Campus Verlag, 2003, p. 176.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Gilomen, The economic foundations of credit and Christian-Jewish competition in the late Middle Ages , pp. 139–169.

- ↑ Hannah Ahlheim, The prejudice of the 'raffenden Juden' , in: Bilder des Jüdischen - Self- and External Attributions in the 20th and 21st Century, DeGruyter, 2013, pp. 235-236.