Battle of the Antietam

| date | September 17, 1862 |

|---|---|

| place | Sharpsburg , Maryland , USA |

| output | tie (strategic victory for the northern states) |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

|

approx. 75,000

|

approx. 38,000

|

| losses | |

|

12,400

2,100 killed 9,550 wounded 750 missing or in captivity |

10,320

1,550 killed 7,750 wounded 1,020 missing or imprisoned |

The Battle of Antietam , also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg , especially in the southern states , was the decisive battle of the Confederate Maryland campaign during the American Civil War . It took place on September 17, 1862 along the Antietam near the village of Sharpsburg , Maryland.

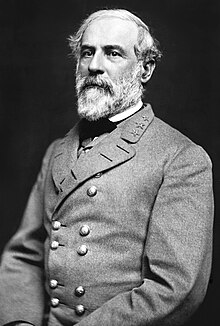

It is considered the most important battle in the eastern theater of war in 1862. After the failure of the Union Peninsula Campaign and the Confederate victory in the Second Battle of Bull Run, General Robert E. Lee commanded the Northern Virginia Army in Maryland. Campaign for the first time on the territory of the northern states. There she faced again the Potomac Army under Major General George B. McClellan . By chance, McClellan came across Lee's detailed operational plans prior to the battle, showing the enemy's vulnerability. However, he missed several opportunities to take advantage.

Although McClellan's troops were nevertheless able to force the Confederates to retreat temporarily with heavy losses in the end, the Battle of Antietam did not result in a decision in the eastern theater of war, but as a missed opportunity for the Union to inflict a devastating blow on the Northern Virginia Army and the civil war to end early. It was the one-day battle with the most losses in the entire civil war. Because of the approximately 3,600 dead and total casualties of around 23,000 men, September 17, 1862 is also known as the "bloodiest day in American history" .

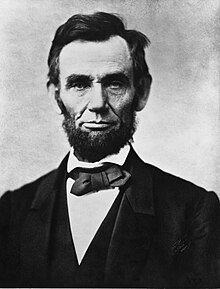

At the same time, its outcome meant a strategic victory for the Union, as, according to leading historians, it is politically considered to be one of the most important turning points of the war. Because even if the military success of the Union troops was ultimately limited, the dearly bought victory gave Lincoln the opportunity to announce his emancipation declaration for the liberation of slaves in the southern states from a position of strength , undermining efforts by Great Britain and France to negotiate a peace the amicable partition of the United States and helped the Lincoln Republican Party avert impending defeat in the fall of 1862 congressional election .

At the Antietam, the consequences of a battle of the civil war were documented in detail with photographs for the first time. Alexander Gardner's photographs of dead soldiers shocked many viewers and led to a more realistic assessment of what had been happening on the battlefields until then, idealized.

Background: The civil war in 1862

Military situation at the beginning of the year

In the second calendar year of the American Civil War, much of the Union's (Northern) efforts in the vital theater of war in the east continued to focus on capturing and occupying Richmond . The fall of their capital, located just 160 kilometers from Washington as the crow flies in Virginia, it was hoped in the north, would inflict a devastating blow on the Confederation (southern states), collapse the government of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the secession of the, which is regarded as a "rebellion" Make the south null and void. To achieve these war goals, the Union had to go on the offensive, while the Confederates could limit themselves to defending their own territory.

One obstacle on the way to Richmond was a series of smaller and larger rivers that ran parallel to the Virginia's border between it and the Confederation capital. First attempts to conquer Richmond had failed in the previous year with the Union's defeats in the First Battle of the Bull Run (July 21, 1861) and in the battle at Balls Bluff on the Potomac (October 21, 1861) at an early stage. Since then, General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate Army , located between Manassas and Centerville , had kept the Union's vastly outnumbered Potomac Army from advancing into Virginia. The result was a stalemate that bothered the north more than the south.

Major General George B. McClellan, Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army, had demonstrated his organizational talent between the summer of 1861 and the beginning of 1862 and formed a well-structured army with new self-confidence from a defeated army. The press had therefore elevated him to the title of “young Napoleon ”. In fact, he was a procrastinator and a perfectionist who shied away from risks and - even when confronted with clearly inferior units - constantly pushed for further reinforcements of his own troops and better preparations for their deployment. McClellan tended to overestimate the numerical strength of the opponent (often many times over) and to justify his lack of initiative with the miscalculation. This made him susceptible to attacks by political opponents who sometimes even assumed he had sympathy for the cause of the South. The charismatic general was nevertheless very popular with his troops.

As a short-term Commander in Chief of the US Army , McClellan achieved a series of successes in other theaters of war in the winter of 1861/2, even if his personal contribution was small. In the west, the Union captured the Confederate fortresses of Fort Henry (February 6, 1862) and Fort Donelson (February 16) in Tennessee , thereby controlling important tributaries to the Mississippi , a possible route to the south , for the first time . The fall of Nashville (February 25) further consolidated the Union's position. Between February and April, an expeditionary army also succeeded in conquering a large part of the Confederate ports on the North Carolina coast .

Attempts by several Confederate armies to prevent further Union advance in Tennessee ended in defeat at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7), the civil war's most costly conflict to date. Union armies then took Corinth , a railroad hub in northern Mississippi (April 30). The fall of Confederate positions and cities along the Mississippi River such as Island No. 10 (April 7), New Orleans (April 24), Baton Rouge (May 9) and Natchez (May 12) completed the series of military successes of the Union in the winter and spring of 1862.

This development made the disappointments of 1861 forgotten and renewed the hope from the beginning of the civil war that the rebellion of the south could end within a few weeks. At the same time, the voices of the pessimists increased in the southern states. As early as February 1862, Confederate Vice President Stephens declared privately: "The Confederation is lost."

Peninsula Campaign and Second Battle of Bull Run

Urged by Union President Abraham Lincoln to go on the offensive, General McClellan drafted a plan in early 1862 to bypass Johnston's supposedly superior force and Virginia's rivers. For this, his army was to be transported by ships across the Chesapeake Bay to the east coast of the state and from there marched on the capital of the Confederation. Lincoln agreed to the venture, although he would have preferred if McClellan had attacked Johnston's army, which is located near Washington on Bull Run , instead of going directly against Richmond.

McClellan's campaign began on March 17th with the landing of the first units of the 120,000-strong Potomac Army at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, about 100 kilometers from Richmond. The Union's advance came to a halt with the month-long siege of Yorktown (from April 5). This gave Johnston enough time to withdraw his force, now known as the Northern Virginia Army, to protect Richmond. Only after a Union victory at Williamsburg (May 5) was the Potomac Army able to advance. Richmond now seemed seriously threatened. Johnston's attempt to stop McClellan with an attack eight kilometers from the city failed due to the undecided outcome of the Battle of Seven Pines (May 31 - June 1), in which Johnston was also seriously wounded.

The command of the Northern Virginia Army now passed to General Robert E. Lee. He had served as a military advisor to President Davis since March 1862 and helped design Major General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah campaign , which had brought the first notable Confederate successes in 1862. McClellan expected a defensive attitude Lee, however, this decided to attack the Union army. Almost all of the fighting in the following seven-day battle (June 25th – July 1st) resulted from attacks by the numerically inferior Confederates. Although Lee's complex attack plans mostly failed and his army suffered high losses, McClellan was impressed by the opponent's varied offensive. He withdrew his troops to the James River , where they stood idle for the remainder of July.

McClellan demanded reinforcements from Washington to counterattack the supposedly 200,000-strong Northern Virginia Army - a three-fold overestimation of its size. As he continued to increase his demands, the exasperated Henry Wager Halleck , the new Commander-in-Chief of the US Army, ordered the withdrawal from the peninsula at the beginning of August. McClellan was to unite his 90,000-strong Potomac Army as quickly as possible with the 40,000-strong Virginia Army under Major General John Pope , which had meanwhile advanced to northern Virginia. Lincoln had the new major union of the Union formed and set up at the Potomac in June, because he saw the city of Washington inadequately protected due to McClellan's campaign. The reluctant McClellan was unsure whether he or Pope would command the assembled army. Therefore he secretly hoped for a defeat of the competitor against several divisions which Lee had sent under the command of Jackson to fight the Virginia Army. McClellan, meanwhile, took his own army back home.

Jackson scored a first success against part of Pope's forces on August 9 at the Battle of Cedar Mountain . With McClellan's army emerging, Lee left 22,000 men to defend Richmond and joined the rest of the Northern Virginia Army to aid Jackson. He was determined to provoke Pope with his 55,000 men to battle before his Virginia Army could unite with the entire Potomac Army.

Sent out by Lee to disrupt Union supply lines, Jackson's divisions looted and destroyed a large Union camp on August 27 in Manassas Junction . Pope decided to provide Jackson with the expected reinforcement by four divisions of the Potomac Army and two divisions withdrawn from North Carolina, before he could reunite his troops with Lees. Not least because of Pope's confused leadership of the units of three armies that had never fought together, the Union troops suffered a humiliating defeat in the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28–30) and had to retreat to Washington via Maryland. In spite of Halleck's orders to the contrary, McClellan had prevented other ready divisions of the Potomac Army from coming to the aid of Pope.

Domestic and foreign policy reactions

"Hard" warfare and slave liberation

The turnaround in the military situation between March and August 1862 was dramatic. If the Union had hoped in the spring to be able to end the war quickly, both major Union associations had to suffer severe defeats in the eastern theater of war in the summer. The failure of the peninsula campaign was repeatedly compared to Napoléon's fiasco in Russia . The Union also experienced setbacks in the summer of 1862 in the western theater of war, although these were not so momentous. The Northern Virginia Army, strengthened under its new Commander in Chief Lee, also threatened to advance into the Northern States for the first time and even to attack Washington, Baltimore and Philadelphia . While in the southern states, after months of largely depressing news from the battlefields, renewed confidence prevailed, in the Union states the certainty of victory turned into astonished horror, sometimes into panic.

In the north, the internal political differences intensified, also because there were elections to the congress in the autumn. The "War Democrats" found themselves in a conflict, ie those members of the Democratic Party who approved the war in principle, but criticized the attitude of the ruling Republicans as too intransigent. They attacked Lincoln because McClellan, himself a Democrat, had not received the reinforcements requested. Many Republicans and supporting newspapers such as the New York Times , for their part, questioned McClellan's account of the balance of power on the peninsula and accused the Commander-in-Chief of the Potomac Army for a lack of will to fight, for being too gentle with the civilian population in Virginia, or even for treason in view of his behavior towards Pope . The criticism was shared by some senior officers in the Potomac Army.

Although President Lincoln was deeply upset by McClellan's inaction since the Seven Day Battle, he resisted appeals from his cabinet to dismiss the general or even to face a war tribunal . Instead, he asked McClellan in early September to continue to lead the Potomac Army, which was united with the troops of the deposed Pope, and to protect the city of Washington from the feared siege by Lee. Lincoln countered violent objections from his ministers with the words: "McClellan has the army on his side [... and] we must use the tools we have."

The doubts about McClellan's loyalty were exaggerated, but he did indeed disapprove of the hard warfare of radical Republicans, to whom he assumed an excessive influence on the despised Lincoln. Like almost all Democrats, McClellan's main opposition was to turn the war for unity into a struggle against slavery in the southern states . With his help, supporters of the general spread rumors that effective military leadership and thus an early victory with few losses and without humiliation of the Confederates would be sabotaged by men like Minister of War Edwin M. Stanton until the more radical war aims could be implemented in public.

Lincoln personally viewed slavery as a moral evil. In the first year of his tenure, however, he opposed the demands of prominent abolitionists and individual party friends to make the liberation of slaves in the south a war goal. Most of all, the president feared that this would lead to the secession of the four slave states that had remained loyal to the Union, the border states of Maryland, Delaware , Kentucky and Missouri . On the other hand, the exploitation of slave labor played an important role in the war economy of the south. The practice of treating escaped or captured slaves from the southern states as spoils of war that did not have to be returned to the "owners" had established itself early on in the Union Army . The Republican-dominated Congress had approved this process on March 13, 1862 by law.

During the summer of 1862, as the Confederate resisted, Lincoln came to believe that the old union of slave and non-slave states could not be restored. The ultimate abolition of slavery should become the foundation of a new union and the southern states should be compelled to accept by all means at their disposal, including tougher treatment of the civilian population. In this change of course, the President was determined to disregard conflicting advice from the military like McClellan and from representatives of the Union's slave states (whom he sought to persuade to voluntarily give up slavery).

On July 22, Lincoln revealed to his astonished cabinet that he had resolved to issue a declaration on the emancipation of slaves in the Confederate states (though not in Union states) based on his wartime rights as commander in chief. Almost all ministers supported the change of course, but Secretary of State William H. Seward warned of the possible diplomatic consequences. In Europe it is speculated that in view of the recent setbacks, the Union must put all its hopes in a revolt of the slaves in the southern states. Therefore, a declaration of emancipation before a major military victory of the Union will possibly be seen as “the last measure of a worn-out government, a call for help” , “our last outcry in retreat” .

In light of Seward's warning, Lincoln decided to postpone the declaration of emancipation for the time being. It was not until the successful outcome of the Battle of Antietam two months later that it was possible to publish it.

Threatening diplomatic recognition of the Confederation

London falls in the back of American freedom struggling with the rebellion.

Caricature from Harper's Weekly , September 1862

The most recent defeats of the Union in the summer and autumn of 1862 threatened to have serious foreign policy consequences for the USA.

From the beginning of the civil war, the Confederation had hoped for its independence to be recognized by the great European powers Great Britain and France and even for their subsequent military intervention in favor of the South. The textile industries of both countries, which had officially declared their neutrality , were dependent on cotton imports from the southern states and the Confederates organized a unilateral export embargo at an early stage in order to exert economic pressure on the Europeans. In Great Britain, many leading politicians felt attached to the “aristocratic” lifestyle of the plantation owners in the south, but viewed the slave economy as an eyesore that stood in the way of recognition. On the other hand, it was pointed out that the Union had not officially made the abolition of slavery a war goal, so that this was not a mandatory precondition for establishing diplomatic relations with the Confederation.

In Europe, people were skeptical as to whether the Union could succeed in subjugating the vast territory of the southern states militarily, but shied away from advocating one side at an early stage. Emperor Napoléon III. tended to be recognized from the start, but only wanted to act in agreement with the British government. In London, however , Prime Minister Palmerston announced as early as 1861 that the Confederation could only count on recognition if it had proven its ability to survive by winning on the battlefield. Charles Francis Adams , Lincoln's ambassador to London, has repeatedly warned his administration of the dramatic consequences of further defeats for the Union.

The worsening cotton crisis and the successes of Jackson and Lee in the Shenandoah Valley and off Richmond actually renewed appeals for recognition of the southern states in Europe in the summer of 1862. President Lincoln, who considered the western theater of war to be more important than the eastern, expressed his displeasure with what he believed to be a distorted perception of the war situation abroad.

In a debate on July 17th, the British Parliament was only dissuaded from calling for a peace settlement on the basis of a partition of the United States through the intervention of the Prime Minister. However, Palmerston himself changed his attitude shortly afterwards. On August 6, he wrote to Queen Victoria that Britain should propose an armistice soon. On September 24th (before news of the Battle of Antietam reached London) he agreed with Foreign Secretary John Russell that in October an initiative coordinated with France for a negotiated peace between northern and southern states would tackle. If Washington rejects this, London will unilaterally recognize the confederation.

Lee's Maryland campaign

Motives and starting position

After the Second Battle of Bull Run, the heavily war-torn Northern Virginia offered no resources to support the victorious Confederate troops for any length of time. General Lee only had the option of withdrawing his army to the Shenandoah Valley or inner Virginia or to lead them across the Potomac to Maryland on Union territory. In a letter to Jefferson Davis on September 3, 1862, Lee advocated the latter option and, in anticipation of a positive answer from the President, began the crossing of the border river with his army the following day. The longer the war lasted, Lee believes, the more the Union's structural advantages, such as its population and modern industry, would come into play. Therefore, the Confederate Army must strike a decisive blow before it is too late.

Lee knew that Virginia politicians and newspapers had long advocated taking the war north. In addition to the psychological aspect of demonstrating the viability of the Confederation to the Union and the European powers, he also promised concrete political results by continuing his offensive: He hoped that the population of the slave state Maryland would use his troops as liberators from the "yoke of the north" welcome and join able-bodied men in the Northern Virginia Army. To further this, Lee had his troops marching to sing the propaganda song Maryland, My Maryland ( sung to the tune of " O Tannenbaum ") , calling on the people of the state to join the Confederation.

Lee also speculated that the incursion into the north could weaken the position of the Republicans, the election of the "Peace Democrats", also known as the " Copperheads ", to Congress , who are increasingly pleading for an end to the war and thus prepare for an amicable dissolution of the Union. If the campaign was successful, an advance into Pennsylvania would be possible, where Lee intended to destroy an important railway bridge over the Susquehanna in order to cut the line of communication with the western theater of war. Meanwhile, a Confederate campaign in the north will prevent a new Union incursion into Virginia and allow defense lines to be expanded and the harvest to be uninterrupted. Because of the strong numerical superiority of the Potomac Army, which had withdrawn to Washington, Lee did not plan the siege of the Union capital feared in the north.

Hopes for support from the Northern Virginia Army in Maryland soon turned out to be deceptive. In the west of the state, where the advance took place, there were few slaves and the population (often of German origin) was largely unionist. The appearance of Lee's army did nothing to change that attitude. After months of marching and fighting, the soldiers were starved and staring at dirt, their uniforms ragged, and often they didn't even wear shoes. Consumption of unripe corn and fruits from the fields and gardens of Maryland caused repulsive diarrhea in many men . The condition of the Northern Virginia Army was so bad that within a week nearly a fifth of soldiers (10,000 out of 55,000) deserted to fight their way back to Virginia. This was due to the fact that many Confederate soldiers supported the defense of their homeland, but rejected an offensive in the north. Draconic punishments could only partially stop the bloodletting. Looting also helped turn Marylanders against the Confederates. The pathetic appearance of Lee's army became a popular subject for commentators and cartoonists in the north.

On the Union side, meanwhile, Lincoln's trust in McClellan paid off, at least for a short time. The general, who is still popular with the troops, succeeded in a limited time in reorganizing the Union's armed forces, integrating the divisions defeated on the Bull Run into the Potomac army and preparing them again for a campaign. On September 7, just ten days after Bull Run, the first of McClellan's units left Washington to join the Northern Virginia Army. The initially subdued mood in the ranks lifted in the face of the friendly, sometimes enthusiastic welcome from the people of Maryland, which was not expected. Previously, the Potomac Army had mainly operated on enemy territory and support from the local population was a new experience for most Union soldiers.

"Lee's lost orders" and first battles

The advance of the Northern Virginia Army in Maryland isolated two places in western Virginia with important Union garrisons: Harpers Ferry (with 10,500 soldiers) at the mouth of the Shenandoah into the Potomac and Martinsburg (with 2,500 soldiers) further west. McClellan wanted the crew to vacate the bases and join the Potomac Army, a move Lee expected. Army Commander-in-Chief Halleck forbade the evacuation. Lee then decided to attack the Union garrisons behind his army, also because he hoped to capture food and equipment in large quantities in Harpers Ferry.

On September 9th, Lee issued his "Special Order No. 191" in Frederick , with which he split his army into four parts. Three divisions under "Stonewall" Jackson were to make a wide arc over Martinsburg and attack Harpers Ferry from the west. Divisions under Major General Lafayette McLaws and Brigadier General John G. Walker were to take the hills east (in Maryland) and south of the village (in Virginia) and bombard the garrison with artillery from there . Lee wanted to hold the position in Maryland with the remaining units west of Frederick between Hagerstown and the South Mountain range . According to Lee's optimistic planning, the four armies should join forces again after just three days.

As is so often the case, Lee was taking a great risk with this division of a weaker army. He trusted, however, in McClellan's timidity demonstrated in the past few months and assumed that the Potomac army would not be operational again before the expiration of three to four weeks.

McClellan's army reached Frederick on the morning of September 13th, three days after Lee's departure, and was celebrated by the local population. A non-commissioned officer resting outside the village came across a copy of Lee's "Sonderbefehl Nr. 191" addressed to the Confederate Major General D. H. Hill shortly after his arrival , which had been wrapped as wrapping paper around three cigars and left lying carelessly on the grass. The meaning and authenticity of the paper were soon recognized and “Lee's Lost Orders” were brought to McClellan. The Commander-in-Chief of the Potomac Army had a unique opportunity: if he set his army on the march quickly enough, it would be possible to separate and defeat the various parts of Lee's army. In a telegram to President Lincoln, McClellan announced, "I have the rebels' plans and will catch them in their own trap."

The hesitant McClellan let 18 hours pass before he set his army in motion. In addition, through an informant from Major General JEB Stuart , the commander of his cavalry , Lee soon learned of unusual activity at McClellan's headquarters . He was awaiting an advance on the three passes at South Mountain. He had enough time to reinforce the Confederate positions there so that the advance of two Union corps could be stopped until nightfall in the fighting on South Mountain on September 14th. Only at the southern pass did the VI succeed. Union Corps under Major General William B. Franklin on the afternoon of the breakthrough.

The Northern Virginia Army lost almost a quarter of its soldiers on South Mountain who were not with Harpers Ferry. The losses were so great and the prospect of being able to defend the remaining passes so small that Lee decided on the evening of September 14 to break off the Maryland campaign and to move the Potomac to Virginia the following day near the small town of Sharpsburg cross. McClellan telegraphed to Washington that his army had won a glorious victory and the Confederates were withdrawing in a panic. Lincoln replied on September 15, “God bless you and all who are with you. If possible, destroy the rebel army. "

Franklin could not fulfill McClellan's assignment to come to the aid of the threatened garrison in Harpers Ferry due to his slow pace. The crew capitulated to Jackson on the morning of September 15, three days later than Lee had calculated. It was the largest surrender of Union troops during the civil war. Jackson's “booty” also included at least 500 people who had fled slavery and were now being deported back to the south. A Union cavalry unit , which broke out of Harpers Ferry on September 14, fell into the hands of a large supply of Confederate ammunition, which they then brought to safety in Pennsylvania.

Meeting at Sharpsburg

Deployment of both armies

General Lee and his troops reached Sharpsburg in the early morning of September 15th. There he received a belated message from Jackson, which spoke of the imminent case of Harpers Ferry. Instantly, Lee changed his stance on withdrawing from Maryland and decided to face the Potomac Army at Sharpsburg. He trusted that the other Confederate units could march there in time.

Lee set up his headquarters in a tent west of the village and placed his troops in a line about four miles long on a range of hills east of Sharpsburg, where the Potomac army was expected to approach. A tree-lined river, the Antietam, running in a sinuous north-south direction, would be a natural obstacle to make the advance of the Union soldiers more difficult. However, the Antietam was only about 18 meters wide in some places, partly shallow and wadable and was crossed by three stone bridges, each 1.5 kilometers apart.

The hills offered a favorable, if not perfect, position of defense. To the southwest of Sharpsburg, steep slopes with good defensive positions extended up to near the Antietam. To the north-east of the village the terrain opened up, the hills were flatter and fields and meadows stretched as far as the Antietam, which, apart from a few woods in between, guaranteed a free field of fire. Along the Confederate lines, fences, limestone ledges, and natural or artificial depressions in the terrain provided cover for soldiers. To the west of the positions there was also a well-developed path, the Hagerstown Turnpike, which could be used to move troops.

Despite these generally favorable topographical conditions, Lee took a great risk at Sharpsburg. In the rear of his army, the Potomac flowed and there was little room for maneuvering. In addition, if they had withdrawn, the Northern Virginia Army would have had only one ford available - Boteler's Ford en route to Shepherdstown, Virginia, southwest of Sharpsburg. In order to save his Maryland campaign, however, Lee was ready to take another risk.

Lee learned of the fall of Harpers Ferry, 20 kilometers south of Sharpsburg, around noon on September 15. He hoped that Jackson's divisions would now march quickly to strengthen the weakened main force of the Northern Virginia Army. Initially, however, Lee at Sharpsburg only had two divisions under the command of Major General James Longstreet and Major General DH Hill's division - a total of about 18,000 men. The worries of his officers that with this number of troops they would be hopelessly inferior to the more than three times stronger Potomac Army, Lee countered with the prognosis that the cautious McClellan would not attack before the beginning of the day after next.

Lee was supposed to be right. A vanguard of the Potomac Army reached the vicinity of Sharpsburg on the afternoon of September 15, but it took all of the following day for McClellan's leisurely advancing troops to take up their positions on the Antietam. Around noon on September 16, the first Confederate troops who had participated in the siege of Harpers Ferry began to arrive in Sharpsburg. At that time, the 69,000 Union soldiers who were within a radius of 10 kilometers east of Sharpsburg were only facing 25,000 Confederates. McClellan assumed, however, that Lee could have three times the number of soldiers.

McClellan moved into the home of the wealthy farmer Phillip Pry, which was on a hill east of the Antietam, as his headquarters. From here he could see the northern and central parts of the later battlefield with telescopes. He intended to maintain contact with his commanders with the help of flag signals that were to be transmitted from a wooden tower. McClellan spent most of September 16 preparing an attack for the following morning, but refrained from properly scouting the positions of the Northern Virginia Army, thus missing Lee's weakness. In addition, McClellan personally took care of the details of the transport of supplies and the formation of the troops, with further precious time passing by.

McClellan's battle plan and its implementation

General McClellan intended to lead the main strike on the left flank of the Northern Virginia Army, northeast of Sharpsburg. The Confederate positions on the range of hills turned here in a western loop to the Potomac and this gave the Union troops enough space to cross the Antietam and advance in the open terrain between rivers and hills. Four divisions of the 1st Corps of the Potomac Army under Major General Joseph Hooker and two divisions of the XII. Corps under Brigadier General Joseph K. Mansfield . The three divisions of the II Corps under Major General Edwin V. Sumner had to be ready east of the Antietam to support the attackers if necessary.

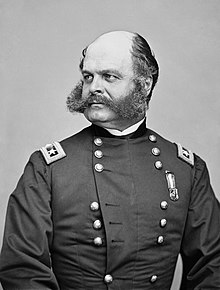

At the same time the four divisions of the IX. Corps under Major General Ambrose E. Burnside attacked the Confederate's right flank in the south to deflect the main blow in the north. McClellan expected Burnside's troops to fight their way through the Antietam and if possible in a wing movement bypassing the Northern Virginia Army and blocking Lee's possible route of retreat across the Potomac to Boteler's Ford.

McClellan paid little attention to the center of the Confederate positions off Sharpsburg, where the central stone bridge was within range of enemy artillery and was therefore difficult to cross. The three divisions of the V Corps under Major General Fitz John Porter were to be ready as reserves east of the Antietam in order to attack in the north or south of the battlefield in the event of a breakthrough by Union troops. McClellan assigned the same function to the three divisions of VI. Corps under Major General Franklin, which were due to arrive at Antietam in the course of September 16, and the cavalry division under Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton , which was part of Mansfield's Corps.

McClellan's battle plan was broadly well thought out, but it required coordination of operations at the corps and division levels, which did not occur. McClellan was personally responsible for this. In contrast to General Lee, he mostly stayed near his headquarters, far away from the battlefield, and was therefore only able to react late to events on the ground. Instead of sticking to the usual three-wing structure of the Potomac Army, he changed the command structure two days before the battle so that all corps commanders had to report to him personally, but did not have to coordinate their operations with each other even when they raised their troops use the same part of the battlefield. Allegedly, rivalries among the Union's generals motivated the new structure. The problem was exacerbated because McClellan only issued individual orders, not a general order to explain the context of all operations.

The lack of coordination meant that more than 20,000 Union soldiers were never deployed at the same time in the Battle of Antietam and Lee always had enough time to relocate his own troops to repel attacks. 20,000 Union soldiers, more than a quarter of the 75,000 available, were not used in combat at all. That McClellan kept Pleasonton's cavalry division in reserve in the center and did not use them for reconnaissance and security on his flanks, turned out to be another serious failure.

Because of these structural and tactical flaws, the Union's two-for-one superiority in battle was almost completely nullified. McClellan's caution resulted - as so often - from the miscalculation of the troops available to Lee at the Antietam. Union officers estimated the strength of the Northern Virginia Army at Sharpsburg at up to 130,000 men.

Course of the Battle of Antietam

Battle the night before

On McClellan's orders, the I. Corps under Hooker crossed the Antietam at about 4 o'clock on the afternoon of September 16. The troops used the northern stone bridge and nearby fords that were beyond the reach of the Confederate artillery. Actually, only the positions for the imminent attack were to be taken, but Brigadier General George G. Meades Division encountered upstream Confederate troops under Brigadier General John B. Hood in a grove (referred to as "East Woods" on military maps) on the northeast edge of the later battlefield . A violent exchange of fire ensued, in which artillery was also used. There were losses on both sides.

As darkness fell, fighting subsided, but artillery fire continued to cover the deployment of McClellan's army. The skirmish did not bring the Union any advantage, but it did reveal to Lee where to expect McClellan's attack that morning and where to strengthen positions. McClellan also continued the preparations for the attack during the night and ordered the XII around midnight. Corps under Mansfield to also cross the Antietam to support Hooker's Corps.

Both commanders-in-chief ordered the division commanders who remained in the vicinity of Harpers Ferry to march quickly with their troops to Sharpsburg. Lee's orders went to Maj. Gen. McLaws, Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson and Maj. Gen. AP Hill , whose Light Division was still in Harpers Ferry, to guard captured Union soldiers and secure the booty. McClellan ordered Major General Franklin to move two of his three divisions. The arrival of all reinforcements by the following afternoon meant that the Potomac Army had to take on Lee's entire Northern Virginia Army, no more than 40,000 strong, on September 17, although the Union's numerical advantage was still 2-1. McClellan had missed his second chance on September 16 to deal a crushing blow to Lee's divided army.

The troops on both sides spent a restless night, disturbed by the occasional exchange of fire and a light drizzle. The approximately 1300 residents of Sharpsburg tried meanwhile to get themselves and their property to safety. Many found shelter in the cellars of their homes or in a large cave on the Potomac. Farmers did what they could to take livestock away from areas where fighting threatened the next day.

Morning: Dunker Church and cornfield

The actual battle of Antietam began at dawn on September 17th at around 5:30 a.m. when General Hooker's I Corps advanced on the left flank of the Confederate, where most of Jackson's II Corps was level with another grove (West Woods) distributed. From there the Confederate positions extended in an arc to the area beyond the Hagerstown Turnpike. Jackson were about 7,700 men available at this point, Hooker about 1,000 men more.

The attack of the Union troops came from northern and northeastern positions along the Hagerstown Turnpike and aimed at an artillery position of the southerners, which was east of this route on a plateau. West of the Hagerstown Turnpike was a small church nearby, which had been built by the pietistic and pacifist sect of the Dunker (= Anabaptist, from the German Tunker) from Germany . On the morning of the attack, ground fog made it difficult for the Union soldiers to see, but the white-painted church building stood out well from its surroundings and thus marked the direction in which the attack by the Potomac Army was to take place. As the Union forces advanced, the Confederate Mounted Artillery under JEB Stuart opened fire. Union batteries located on a range of hills on the northern edge of the battlefield shot back. The first fighting occurred in front of the eastern grove, where a Confederate brigade was able to push back several Union regiments.

Most of the land between the Union forces and the Confederate positions took up pasture land. In the exact center, north of the plateau, however, was an approximately 8 hectare corn field in which the stalks were more than a man's height. While advancing, the Union troops discovered through bayonet points flashing in the sun that Confederate soldiers were hiding in them. Hooker ordered the advance to be halted and this confusing section of the front to be bombarded with four batteries. The mutual artillery and rifle fire that developed was so violent that the cornfield was mowed down like a scythe. Hooker later wrote in his report:

" ... every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battle-field. ... "

“… Even the last stalk of corn in the northern and largest part of the field was neatly cut off as if with a knife and the fallen were exactly in the ranks in which they had been in battle a few moments before. Never before has fate made me a witness to such a bloody, desolate battlefield. ... "

The Union troops were now advancing on a line about 800 meters long. Fierce exchanges of fire broke out again in front of the eastern grove, where a Union brigade fought its way into the cornfield but was unable to break the resistance of an outnumbered Confederate brigade from Georgia. The Union troops also encountered bitter resistance on their right flank, but were able to gain ground in the western woods and in the maize field and gradually approached the plateau. The Hagerstown Turnpike was flanked by partly high wooden gates that could be used as cover, but also exposed the soldiers when climbing over, which made them easy targets for snipers. As there was a violent struggle for the area on both sides of the path that morning, the gates developed into a deadly trap for many soldiers.

Union soldiers had moved close to the plateau south of the cornfield when Jackson's repulsed troops were reinforced by General John B. Hood's division. It had been kept in reserve by Jackson as the soldiers were exhausted after the fighting the previous evening and were supposed to rest. Hood's men were allegedly angry and therefore particularly motivated to fight the Union Army because they had to interrupt the first hot breakfast for days to do their job. They were able to push the enemy troops back through the corn field, but suffered heavy losses. The Division's 1st Texan Regiment lost 82% of its soldiers in just 30 minutes. Even so, the advance of Hood's division saved the left flank of the Northern Virginia Army from collapse. The attack by Hooker's I. Corps came to a halt.

McClellan had failed to prevent Hooker's attack by the two divisions of the closely related XII. Support Mansfield Corps. When the XII. Corps finally intervened in the fighting from the eastern grove around 7:30 a.m., Hooker's troops were already too exhausted for the Union to derive a decisive advantage from them. There was enough time for General Lee to face the Union's second wave of attacks with the dispatch of three new divisions. Nevertheless, the XII. Corps to drive Hood's troops out of the cornfield and a Union brigade even managed to take the Confederate batteries on the plateau near the Dunker Church in the course of the attack.

Meanwhile, however, Mansfield had been fatally wounded. Hooker was also hit in the foot by a Confederate sniper's bullet and had to be carried off the battlefield. The loss of the two commanding generals on the northern section of the front unsettled the Union troops and the brigade on the plateau withdrew from the western grove after heavy counterfire from the Confederates. The command of the I. Corps was now transferred to Brigadier General Meade, the command of the XII. Corps to Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams .

After three and a half hours of fighting, at 9 a.m., over 8,000 men were dead, wounded or missing on the northern section of the front without either side having gained any significant advantage.

McClellan had initially held back the three divisions of the Second Corps of the Potomac Army under Major General Sumner far east of the fighting near his headquarters. It wasn't until 7:20 a.m. that he sent two of Sumner's divisions to the battlefield, where they didn't arrive until an hour and a half later. Without coordinating his actions with Meade and Williams, Sumner ordered his two divisions, under the command of Major General John Sedgwick and Brigadier General William Henry French , to attack the Confederate left flank again at around 9 a.m. The enterprise was so hasty that French's division lost touch with the advance on the eastern grove. Obviously disoriented as to where to direct his troops, French ordered a left turn to circumvent the plateau to the south. He so inadvertently led his men to the middle Confederate positions outside Sharpsburg, where no fighting had yet taken place.

Sumner only had 5,400 men from Sedgwick's division for his attack. These were able to advance almost unhindered over the cornfield and Hagerstown Turnpike. The apparent retreat of the Confederates turned out to be a trap, however, because Jackson's troops, which had again been joined by fresh divisions, took the Union soldiers under fire from three sides as they reached the western grove. Since soldiers in the back ranks of the Union feared meeting their own comrades, they were targeted without being able to return fire. After less than half an hour, Sedgwick's division had to pull back. It had over 2,000 dead, wounded and missing. Seriously wounded also included the young Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. , who would later become a Supreme Court Justice . A subsequent Confederate counter-attack on the meadows in front of the western grove was answered with artillery fire from the Union and had to be broken off.

The last major skirmishes on the northern part of the battlefield took place around 10 a.m. when two regiments of the XII. Union Corps tried again to implement Hooker's original plan and advanced from the eastern grove to Plateau and Dunker Church. The attack came to a halt due to Confederate resistance and a lack of reinforcements, but the Union troops recorded minor gains in land between the cornfield and the western grove.

This ended the first phase of the battle after four hours with more than 12,000 casualties, including two commanding generals of the Union. Five divisions of the Union and four of the Confederate were so badly affected that they could no longer intervene in the rest of the war that day. McClellan's plan to roll up the left flank of the Northern Virginia Army had failed. Since the attack of the Union troops did not take place in one massive blow, but rather successively, the strong numerical superiority of the Potomac Army on this part of the battlefield was never fully exploited. The result was a series of loss-making skirmishes over a relatively small area, which ultimately ended in a stalemate. According to eyewitness accounts, the cornfield alone had changed hands fifteen times that morning.

Noon: Bloody Lane

In the meantime, fighting had developed at the center of the Confederate positions off Sharpsburg, triggered not by McClellan's order to attack, but by Brigadier General French's error. When his division encountered Confederate skirmishers on a farm southeast of Dunker Church, he decided to take up the fight here. Shortly after 9:30 a.m. he received a message from Major General Sumner, who informed French of the debacle of the Union troops in the western grove and ordered an attack off Sharpsburg to force the Confederates to withdraw troops from the north of the battlefield.

The center of the positions of the Northern Virginia Army was under the command of Major General Longstreet. The defense was weak, because units had been deployed to reinforce Jackson's corps during the morning. Since then the five brigades of Major General DH Hill's division held the position; three of them had already suffered losses in the course of the morning fighting. The best defensive position was possessed by two brigades, holed up 100 yards behind a ridge in a dirt track that arched between Hagerstown Turnpike and Boonsboro Road. Erosion and truck traffic had shaped it into a deep ravine (known as Sunken Road by local residents) that formed a natural trench. Artillery had not been positioned on either side of this section of the front.

French was hoping for some surprise when he commanded his division up the hill to Sunken Road. This failed because the entrenched Confederates, seasoned veterans, awaited the attack and patiently withheld fire until the enemy got into a position at the crest of the hill where they could easily be hit. The leading brigade of the Union under Brigadier General Max Weber , which consisted mainly of German immigrants without much combat experience, suffered particularly heavy losses . She lost 450 men in just five minutes. A subsequent assault by Colonel Dwight Morris' similarly inexperienced Second Brigade was also repulsed. French now sent his last and best brigade into battle, but they too failed when attempting to advance to Sunken Road. In less than an hour, French's division had lost nearly a third of its soldiers on the hill.

The Confederate Brigades on Sunken Road received reinforcements on the right from Major General Anderson's division. Encouraged by this, the Confederates were preparing to flank down the hill at about 10:30 a.m. when the last of Sumner's divisions, commanded by Maj. Gen. Israel B. Richardson , arrived. McClellan had held them back when the rest of Sumner's corps had marched to the battlefield and hadn't sent them off until nine o'clock. Richardson ordered another attack, but the famous Irish Brigade was also wiped out without reaching Sunken Road.

It was now noon and the defense of four consecutive frontal attacks by the Union had also taken a heavy toll on the defenders on Sunken Road. Anderson had been seriously wounded early on (he succumbed to his injury four weeks later) and no one took command, so his division was of little help. The middle of the defensive line was particularly weakened, where the ravine made a sharp bend and the natural trench was so narrow that the Confederates were often hit by ricochets that ricocheted off the back bank.

When Confederate Brigadier General Robert E. Rodes ordered the Union to redistribute troops during the fifth attack to strengthen the center, a regimental commander misunderstood him and ordered a withdrawal from Sunken Road. The four remaining regiments of the brigade joined the action, which degenerated into a wild flight, without Rodes being able to do anything about the collapse of the defensive line. The advancing Union soldiers then took Sunken Road and captured 300 Confederates. In many places along the ravine, the dead were now lying two or three on top of each other.

When the Union troops regrouped on Sunken Road, they were attacked from the north by two Confederate regiments, who suffered heavy losses in the action and had to withdraw. While French's division secured Sunken Road, Richardsons marched on the new Confederate line of defense, located less than 300 yards southwest on farmer Henry Piper's property. Meanwhile, Major General DH Hill had pulled together the remains of his division, and it attacked Union forces in a corn field on the Piper farm. The advance of the weakened unit was doomed to failure, but bought General Longstreet time to consolidate the Confederate line before Sharpsburg by drawing together guns; their fire halted the Union's advance. An intact infantry was no longer available to Longstreet at this time. The remaining units were each hardly larger than a few hundred men and some had no more ammunition.

Reluctantly, due to Confederate artillery fire, Richardson withdrew his division, which had already lost over 1,000 men, to the hill north of Sunken Road. Here one expected the arrival of requested artillery in order to be able to take out Long Street's artillery, but received only inadequate cannons, which could not reach the Confederate positions. While discussing the situation with a battery commander, Richardson was badly wounded by a fragment of a missile around 1:00 am and transported to McClellan's headquarters in the Pry House, where he succumbed six weeks later. Brigadier General Winfield Scott Hancock took command, but in the meantime another favorable opportunity to break the Confederate line, which was on the verge of disintegration, passed.

In three and a half hours, over five and a half thousand men were killed, wounded or missing in the immediate vicinity of the 700-meter-long section of the front on Sunken Road. The losses amounted to nearly 2,600 men in the Confederate and nearly 3,000 men in the Union soldiers. The carnage gave Sunken Road the new name Bloody Lane.

Despite their higher casualties, the Potomac Army had fought for an advantage in the center of the Confederate positions off Sharpsburg. In addition, McClellan had two fresh corps available that could be used to attack the Northern Virginia Army: the V Corps under Porter and the Pleasonton Cavalry Division, a total of 13,800 men, and the 12,000-strong VI. Corps of the Union under Major General Franklin, which had arrived at Antietam around noon from Harpers Ferry and, on McClellan's orders, was now securing the Union line to the north.

Franklin wanted to start a new attack at around 1 a.m. in the western grove, but was held back by the older and higher-ranking corps commander Sumner, who was shocked by the unbelievable blood toll of the previous skirmishes. Another setback, so Sumner's reasoning, will put the entire right flank of the Union in danger. McClellan initially leaned towards Franklin's point of view, but after consulting both officers on site, decided to change. He gave instructions not to undertake any further attacks in the north and in the center of the battlefield.

Afternoon: Burnside Bridge and Counterattack Hills

To the southeast of Sharpsburg, the IX. Corps under Major General Burnside should wait for an order from McClellan before starting its feint attack. By the time the order from Headquarters finally reached Burnside around 10 a.m., the fighting on the northern section of the front had already subsided and the company's original goal had become obsolete. Burnside, however, apparently still assumed that he was responsible for a diversion that did not need to be tackled with full force. He did not understand (or was not told) that the main burden of the Union's attack was now on his troops.

Burnside's 13,000 soldiers now faced fewer than 4,000 Confederates, the latter mainly in positions spread over a hill in front of Sharpsburg, later known as Cemetery Hill. Lee had withdrawn a division and an additional brigade from his right flank to repel attacks by the Union in the northern and central sectors of the front.

Due to inadequate exploration of the site, Burnside - unlike McClellan's experts the day before - had hidden a nearby ford that would have allowed the Union infantry to cross the Antietam with comparative ease. Therefore, Burnside focused on taking the Rohrbach Bridge (Rohrbach's Bridge), a nearly 40 meter long, 3.70 meter wide, three-arched stone bridge and southernmost crossing of the Antietam at Sharpsburg. It was defended by 550 upstream snipers from Georgia under the command of Brigadier General Robert A. Toombs . They spread along the Antietam, taking the bridge under fire from the safe cover of rocky outcrops, stone walls, and trees.

Before the stone bridge attack began, Burnside dispatched three brigades to cross a ford a kilometer south that McClellan's scouts had also spotted the day before. When the troops reached the designated point, however, they found that the embankment there was too steep. The men fought their way through thick bushes in a lengthy maneuver to the south-west and finally came to Snavely's Ford, where a transition was possible.

It was now noon and the Confederates had already repelled two attacks on the stone bridge. McClellan lost patience and instructed Burnside to take the bridge even at the cost of heavy losses. The third attack began around 12:30 p.m. and units of the IX. Corps after about half an hour to establish themselves at the eastern end of the bridge. The snipers from Georgia ran out of ammunition and from the southern flank Toombs received the news of the transition of the Union forces via Snavely's Ford. Burnside's troops had been held up for three hours by a twenty-fold defeated unit and, with 500 men, suffered more than three times the casualties of Toombs' Georgians.

The right flank of Lee's army was now in dire straits. Three of Burnside's divisions threatened to invade weakened troops on General Longstreets. But the approach of unspent units of the IX. Corps that remained at some distance from the bridge, the transport of ammunition supplies and the crossing of the narrow bridge proved to be lengthy operations that cost Burnside two valuable hours (a ford that had meanwhile been discovered north of the bridge remained unused). McClellan's anger at these delays was directed at Burnside. He sent out several couriers to urge his general to take more forceful action.

The sluggishness of the Potomac Army gave General Lee enough time to move troops and artillery to his right flank from other sectors of the front where the fighting had since stopped. For a short time, the Confederates even considered a relief attack in the north of the battlefield, which would be led by Stuart's cavalry. Jackson broke off the operation, however, given the massive superiority of the Union artillery. After an eight-hour forced march from Harpers Ferry, to Lee's great relief, the Hills Light Division finally arrived at Sharpsburg at around 2:30 a.m. She had crossed the Potomac through Boteler's Ford, which was still open. Hill's men were ordered to reinforce Long Street's troops.

When the IX. Union Corps had re-formed at the bridgehead on the west side of the Antietam, Burnside started a two-wing attack on the Confederate's right flank with 8,000 men around 3 a.m. The advance was initially successful and the defenders fell back in the direction of Sharpsburg. In the village itself there was chaos with the many wounded people being carried through the streets, numerous dispersed soldiers whose units had been worn out and the shelling by the Union artillery, which damaged a number of buildings so badly that they later had to be demolished.

With Hills Division 3,000 men intervening, the tide turned at about 3:40 a.m. The Northern Virginia Army was able to counter-attack and the far left flank of the IX. Union corps was in grave danger. Confusion arose among Northerners because many of Hill's men wore Union blue uniforms that had fallen into their hands at Harpers Ferry. Burnside, disconcerted by the surprising turn of the battle, withdrew his troops to the Antietam. Although he had twice as many men as the opponent in the field, he was worried that it would not be possible to hold the bridge that had been hard-won over. He asked McClellan to send promised reinforcements that morning. McClellan's fear had been renewed that Lee still had unimagined powers. Avoiding the risk of running his reserves into a massive counterattack by the Northern Virginia Army, McClellan sent Burnside only one battery.

The fact that McClellan's fears were far removed from the reality went by a battalion of the Union's 5th Corps in reserve. While advancing over the middle stone bridge on Boonsboro Road, the men discovered the vulnerability of the middle lines of defense near Sharpsburg. Brigadier General George Sykes , in command of the 2nd Division of V Corps, insisted that his men be allowed to cross the bridge into battle to aid Burnside. McClellan, who seemed convinced of the proposal, abandoned it after consulting Corps Commander Porter. From this conversation Porter's saying has come down to us: "General, consider that I command the last reserve of the last army of the republic!"

The Northern Virginia Army had been saved by the timely arrival of the AP Hills Light Division. The IX. Corps of the Potomac Army had no other task than to secure the stone bridge on Antietam, which had been captured with heavy losses. Because of what happened that day, the structure was later renamed Burnside Bridge (Burnside Bridge or Burnside's Bridge).

losses

The losses in the Battle of Antietam were high on both sides. For the Union, 2,100 soldiers were killed and 9,550 wounded, 750 Union soldiers were missing or were taken prisoner. Among the Confederates, 1,550 soldiers were killed and 7,750 wounded, 1,020 were missing or had been captured. Six generals were killed or fatally wounded, three each from the Union and three from the Confederation. In the days and weeks after the battle, at least 2,000 wounded died from their injuries.

To this day, September 17, 1862 is considered "the bloodiest day in American history" . More Americans fell on the Antietam in a single day than had been the case in any previous or subsequent war involving the United States. The number of dead and injured at Sharpsburg was four times the number of American casualties on D-Day during the Normandy landing in 1944. More American soldiers died on the battlefield at Antietam than in any other war of the 19th century Century taken together.

After the battle

General McClellan wrote to Washington the morning after the battle that the fighting would likely resume the same day. Even then, however, he made no move to put this into practice, but rather waited for Lee to act. The agreement of a ceasefire with the Confederates to rescue the wounded signaled that there would be no further fighting on September 18. With up to 13,000 reinforcements arriving that day and his 20,000 soldiers who had not been deployed the day before, McClellan would have had more fresh forces available for a new offensive than Lee had any soldiers left in the field. Then there were the 30,000 Union soldiers who were uninjured during their combat mission the day before. McClellan's decision not to continue the attacks, later often criticized, was in line with the attitude of most officers and soldiers in the Potomac Army.

Lee, for his part, initially did not withdraw his troops after a battle in which they were on the verge of defeat several times, despite the adverse circumstances. Instead, he even considered attempting an attack on September 18. Not until the night of September 19 did the Northern Virginia Army retreat to Virginia via Boteler's Ford. McClellan sent her first a brigade for violent reconnaissance and on September 20 a few regiments from Porter's V Corps followed. However, the troops deployed were too weak to achieve anything. In the battle at Shepherdstown (September 19-20) the Confederates won. Lee originally intended to resume the campaign after briefly staying in Virginia, but informed President Davis on September 25 that the condition of his army did not allow it.

Because of the withdrawal of the Confederates, it fell to the Union to treat the wounded and bury the dead on both sides. In the wide area around Sharpsburg private houses, barns and stables were converted into auxiliary hospitals, in which the local population also helped. Funeral troops made up of Union soldiers took on the task of burying the dead. They worked until September 24th. As the action had to be taken in a hurry, many of the mass graves were not dug very deep. Confederate soldiers who passed Sharpsburg during the Gettysburg Campaign the following summer saw numerous carcasses whose graves had been washed away by the rain or dug up by pigs.

Consequences of the Battle of Antietam

Historians generally agree that the Battle of Antietam was one of the turning points in the American Civil War, perhaps the most momentous. James M. McPherson summarizes the political and military consequences of the event as follows:

“ The Union's victory at Antietam, limited as it was, ended the southern military momentum, prevented foreign recognition of the Confederation, reversed a catastrophic decline in the will to fight among soldiers and civilians in the north, and gave Lincoln the opportunity to publish a declaration of emancipation. In a war with several important turning points, the Battle of Antietam was the key moment for the most important one. "

Declaration of emancipation and congress elections

For two months, Lincoln had waited tense for a military success by the Union and thus for the opportunity to publish the secretly prepared declaration of emancipation. In a cabinet meeting on September 22nd, the president indicated that he saw the outcome of the meeting at Sharpsburg as a divine sign to act, even if the rebels had not been crushed. He announced the immediate publication of a preliminary declaration of emancipation. The confederate states would then have time until the end of the year to rejoin the union, otherwise the slaves in these states should be "forever free" from January 1, 1863 .

The declaration of emancipation was enthusiastically received by abolitionists such as Horace Greeley and Frederick Douglass . The former slave Douglass put his feelings in the words: "We are delighted that we are allowed to experience this just decree." Some opponents of slavery criticized the fact that the slaves in the border states of the Union were not affected, but the majority recognized that that Lincoln could only rule on "enemy property", but not on the property of the population of Union states.

The declaration of emancipation met with almost unanimous rejection from the Democrats. There were also protests in the border states, but this no longer impressed Lincoln. There was great resistance in the ranks of the Potomac Army, especially among followers of McClellan, who accused the president of wanting to provoke a slave revolt in the south. McClellan saw this as a nefarious strategy. The grumbling of his subordinates was so strong that McClellan had to issue a general order to counter rumors of an impending military coup. In it, he declared that there was only one antidote to political error, namely to vote correctly at the ballot box - a clear attempt to campaign public opinion in favor of the Democrats.

The main topics of the Democrats in the election campaign were the declaration of emancipation and the partial suspension of the habeas corpus provisions of the constitution (also announced after Antietam von Lincoln) . The partial repeal allowed the government to bring radical opponents of new recruits to the Union army, decided after the failure of McClellan's peninsula campaign, to military courts. If there was agreement on these points in the rejection, the dispute between "war democrats" and "peace democrats" put a strain on the party's credibility. The Republicans took advantage of this in the election campaign and exaggerated the intra-party influence of the "peace democrats". The elections, which took place between September and November, eventually brought Democrats gains in the House of Representatives and states, but losses in the Senate . The Republicans retained a majority in both houses of Congress - an important prerequisite for the continuation of Lincoln's war policies. The battle of Antietam had swayed the electorate in favor of the Republicans. Before September 17th, a democratic majority in the new House of Representatives was generally expected.

Reactions in Europe to Antietam and the Liberation of Slaves

The Battle of Antietam undermined the British government's intention to initiate a mediation initiative with the prospect of subsequent Confederation recognition. Prime Minister Palmerston wrote to Secretary of State Russell in early October that they would wait until the war situation became clearer. A few weeks later it became clearer. The defeats of the south had clouded the prospect of a successful mediation for the time being and he was now convinced "that we only have to remain in the spectator role until the war has taken a more decisive turn."

France sought the support of the British and Russian governments for a proposal for a six-month ceasefire that would allow the Union to unblock Confederate ports and resume cotton exports, but the governments of both countries refused. In a letter to the Belgian King Leopold I , who also advocated mediation, Palmerston explained in mid-November that the previously expected opportunity for such an undertaking had not materialized due to the military setbacks of the Confederates.

The part of the British public leaning towards the Confederation, above all The Times , condemned the declaration of emancipation as a cynical measure by Lincoln, which was not based on indignation over slavery, but was intended as a political maneuver to mislead foreign countries and incite slaves into a bloody uprising. Prounionist forces in Great Britain contradicted this and recognized a serious step by Lincoln to abolish the abhorred slavery. When the final text of the Declaration of Emancipation included a passage calling on freed slaves to renounce violence, support for the Union grew in Britain and other European countries. Lincoln's move had morally legitimized the North's war aims. As a result, recognition of the confederation was no longer seriously considered in Europe. Henry Adams , the son of the American ambassador, wrote back home from London on January 23, 1863: "The declaration of emancipation has achieved more for us here than all of our previous victories and all of our diplomacy."

Consequences for the perception and course of the war

Two days after the fighting ended, the photographer Alexander Gardner began to capture the terrible consequences of the Battle of the Antietam. During two stays in Sharpsburg, he took around 90 photographs of the village, the battlefield, and living and dead soldiers, around 70 of them using stereoscopy , which was supposed to give the viewer a three-dimensional impression. The photos were presented in October 1862 in a well-attended exhibition in the studio of Gardner's employer Mathew B. Brady in New York and then reproduced as an attraction for stereo viewing devices. For technical reasons newspapers and magazines could not yet reproduce photos, but Harper's Weekly magazine used them as a template for illustrations. Gardner's harrowing photos of mutilated and bloated corpses in particular were a novelty in the documentation of the civil war. Although the depicted dead were almost without exception fallen Confederates (probably out of fear that pictures of dead Union soldiers could reduce support for the war in the north), the public perception of the battle, which had been romanticized until then, changed as a result.

Unlike most battles in the Civil War, the Battle of Antietam was fought in just one day. Six other encounters that took place in one place and stretched over several days, the losses were higher: Gettysburg , Chickamauga , Wilderness , Chancellorsville , Shiloh and Stones River . With the exception of Shiloh, these encounters took place after the Battle of Antietam. In the memory of many participants who were able to make comparisons, Antietam was nonetheless considered the worst battle of the civil war. The fighting over the cornfield, Bloody Lane and Burnside Bridge, in particular, epitomized the high blood toll that soldiers on both sides had to pay in this conflict.

The press in the north hailed the outcome of the battle, the Confederate withdrawal from Maryland, as a great Union success, the first real victory in the eastern theater of war. Less than three weeks after Bull Run, the fate of the war had fundamentally changed in the public perception. After a series of failures and bloody defeats, the ranks of the Union at Antietam had not collapsed. Rather, the north had repulsed the Confederate invasion and apparently usurped the initiative. Although journalists and the ranks of the Potomac Army occasionally criticized their failure to destroy Lee's army, Union soldiers' morale improved noticeably.

Conversely, in the Confederation, the rapid termination of the Maryland campaign was mostly felt as a defeat. The newspapers tried to counter the pessimism and especially highlighted Jackson's success at Harpers Ferry. This harmonized with the perception of numerous Confederate soldiers, who emphasized that they had not been beaten, but rather intimidated the Union army so that they refrained from resuming the fighting on the Antietam. Individual participants in the Maryland campaign, however, admitted their disappointment that the Confederate attempt to go on the offensive had failed. General Lee himself was dissatisfied with the indiscipline shown by many of his soldiers in Maryland, but did not make his reservations public. Public anger in the southern states particularly aroused the residents of Maryland, who did not meet the expectations of the south. The disappointment was soon repeated with regard to Kentuckys, where the Confederates also tried in vain during incursions to drive the population into an uprising against the Union.

In the weeks following the battle, the Potomac Army remained inactive in their camps, despite good weather and growing press resentment that the advantage gained at Antietam was not being used. The Potomac was only crossed to recapture Harpers Ferry. Lincoln urged McClellan to attack Lee's army, which was still in northern Virginia, but was unsuccessful. During an extended visit to Sharpsburg in early October, the President renewed his call for a vigorous offensive against Lee's army in dialogue with McClellan and received evasive replies from the General.

Lincoln's displeasure with McClellan was compounded by a spectacular and successful raid carried out by Lee's cavalry between October 12 and 14. JEB Stuart managed to advance with 1,800 men as far as Pennsylvania, to make extensive booty there and to circle the entire Potomac army without the Union cavalry intervening. The Confederates lost only two men in the commando operation.

In mid-October, in several letters expressing growing anger, the president rejected McClellan's flimsy justifications for not following Lee across the Potomac. A letter from Lincoln October 13th said, “Aren't you overly cautious about assuming you cannot do something the enemy is constantly able to do?” Army Commander-in-Chief Halleck summarized his frustration with the inaction of the Potomac Army: “ There is a standstill here that surpasses anything a person can imagine. Archimedes' lever is needed to set this inert mass in motion. "

It wasn't until October 26 that McClellan's army followed Lee across the Potomac, but the operation took nine days - compared to the few hours it had taken the Northern Virginia Army after the Battle of Antietam. Lee was not impressed by the overwhelming power of the Union and divided his weaker army as usual: Jackson's corps was to threaten McClellan's flank from the Shenandoah valley, and Longsstreet's corps was to protect Richmond. The tentative advance of the Potomac Army in the face of this constellation finally convinced Lincoln of McClellan's unwillingness to attack the enemy.

On November 9, Lincoln deposed McClellan as Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army. He had waited until the congressional election was over to move. McClellan's place was reluctantly Major General Burnside, who was to prove at the Battle of Fredericksburg a month later that he was not up to the task. McClellan rejected calls from officers and troops to march on Washington to overthrow Lincoln and initially withdrew into private life. After that, he never entered a battlefield again. As a Democratic rival Lincoln in the presidential election in 1864, he was unsuccessful.

In later writings, in which he justified his strategic decisions with increasing stubbornness, McClellan reiterated his conviction that he had personally saved the Union in September 1862 and won a great victory at the Antietam. Most Civil War historians, however, do not stress the Union's successes in Maryland (say, that it would take Lee nine months to return to Union territory), but rather McClellan's missed opportunities to defeat the Northern Virginia Army and all to shorten the war. A. Wilson Greene takes the dominant view when he writes: “Between September 13-18, 1862, George McClellan wasted the best opportunity ever to destroy the Confederation's main regional army. The nation paid the price for its failure during 31 additional months of civil war. "

Coordinates: 39 ° 28 ′ 23.5 " N , 77 ° 44 ′ 40.9" W.

literature

Source editions

- Jay Luvaas, Harold W. Nelson (Eds.): The US Army War College Guide to the Battle of Antietam, the Maryland Campaign of 1862 . South Mountain Press, Carlisle 1987, ISBN 0-937339-01-6 .

Representations

- Ronald H. Bailey: The Bloodiest Day. The Battle of Antietam . 2nd edition Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Va. 1985, ISBN 0-8094-4740-1 .

- Benjamin Franklin Cooling. Counter-thrust. From the Peninsula to the Antietam . University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-1515-3 .

- Gary W. Gallagher (Ed.): Antietam. Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign . Kent State University Press, Kent and London 1989, ISBN 0-87338-399-0 .

- James M. McPherson: Crossroads of Freedom. Antietam . Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2002, ISBN 0-19-513521-0 .

- Lt. Col. Joseph B. Mitchell: Decisive Battles of the Civil War , New York 1955, ISBN 0-449-30031-5 , pp. 45-51.

- James V. Murfin: The Gleam of Bayonets. The Battle of Antietam and Robert E. Lee's Maryland Campaign, September 1862 . Emphasis. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge 2004 (1965), ISBN 0-8071-3020-6 .

- Joseph Pierro (Ed.): The Maryland Campaign of September 1862. Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam . Routledge, New York et al. a. 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-95628-4 .

- John Michael Priest. Antietam. The Soldiers' Battle . Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford 1993 (1989), ISBN 0-19-508466-7 .

- Stephen W. Sears: Landscape Turned Red. The Battle of Antietam . Ticknor & Fields, New Haven et al. a. 1983, ISBN 0-89919-172-X .

Web links

- National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 31 (English)

- Preparation of a military-historical field briefing for staff officers of the US Army (English)

- Animation of the battle by the American Battlefield Trust

- Further links / literature

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stephen W. Sears: George B. McClellan. The Young Napoleon . Ticknor & Fields, New York 1988, ISBN 0-89919-264-5 , p. 303.

- ^ Sears: McClellan . P. 303.

- ^ Website of the Antietam National Battlefield: Casualties of Battle. Union . (on November 24, 2008)

- ^ Website of the Antietam National Battlefield: Casualties of Battle. Confederate . (on November 24, 2008)

- ↑ In the original: "The bloodiest single day in American history" . See: James M. McPherson: Crossroads of Freedom. Antietam . Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2002, ISBN 0-19-513521-0 , pp. 11-12.