Carl-Gustaf Rossby

Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby (born December 28, 1898 in Stockholm ; † August 19, 1957 there ) was a Swedish meteorologist who was also a US citizen from 1939 . He contributed significantly to the description of the large-scale movements of the atmosphere with the help of fluid dynamics . He discovered the Rossby waves , first described the concept of potential vorticity and also made contributions to oceanography .

Rossby acquired the methods of the " Bergen School " founded by Vilhelm Bjerknes during a one-year stay in Norway in 1919/20 and from 1926 onwards spread and developed them in the USA. There he initially worked for the US Weather Bureau and was involved in founding the first weather service for civil aviation . He then conducted research from 1928 to 1938 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), from 1941 to 1947 at the University of Chicago and from 1947 to 1955 at Stockholm University , where he established important meteorological institutes. In World War II he coordinated the training of several thousand US military meteorologists.

Rossby is considered one of the most important meteorologists of the 20th century. The American Meteorological Society awards him the Carl-Gustaf Rossby Research Medal in his honor , and the Rossby waves and the Rossby number are named after him.

Live and act

Origin, childhood and school education

Carl-Gustaf Rossby was born as the eldest child of Arvid and Alma Charlotta Rossby (née Marelius) in Stockholm; he had three brothers and a sister. His father worked as a civil engineer in the Swedish capital, his maternal family ran a pharmacy in the old town of Visby on the Baltic island of Gotland . The family also spent numerous summers there, where the young Carl-Gustaf developed a keen interest in botany and orchids . At school, Rossby first received a classical humanities education. He passed his university entrance examination (student exam) in Latin in 1917, before passing the additional examination in the natural sciences a week later, in which he was already very interested at the time.

Rossby had suffered from chronic heart disease since developing rheumatic fever in his childhood that very few people outside of his family knew about. Because of this illness, he was released from military service.

Stockholm, Bergen and Leipzig (1917–1925)

Rossby first took up a degree in medicine before switching to the mathematical sciences. In 1918, after less than a year, he finished his studies at Stockholm University in astronomy , mathematics and mechanics with a bachelor's degree ( filosofie kandidat ), according to his companion Tor Bergeron, an “outstanding result, since this course should and often last three years took significantly longer ”.

After graduating, Carl-Gustaf Rossby continued his studies at Stockholm University for a year, including a lecture by Vilhelm Bjerknes . Although he had no further previous meteorological knowledge at that time, he applied at the suggestion of his mathematics professor Ivar Bendixson as a scientific assistant to Bjerknes, who was now doing research in Bergen , Norway . Bjerknes and his colleagues had set up the Bergen School there since 1917 , which combined theoretical and experimental methods for weather forecasting and had recently described the polar front theory for the first time.

Rossby arrived in Bergen on June 20, 1919, where he proved to be a versatile source of ideas and a good organizer. Among other things, the convention that still exists today to mark warm fronts in red and cold fronts in blue on weather maps goes back to a proposal by Rossby in the summer of 1919. Working with Erik Bjørkdal and Tor Bergeron, he learned the practical methods of weather forecasting that the Bergen School was developing at the time. But he found greater liking in theoretical fluid dynamics , which Bjerknes had made a significant contribution to embedding in meteorology. However, during Rossby's stay it only played a subordinate role compared to the practical work with technical equipment and weather maps.

At the turn of the year 1920/21 Rossby left Bergen for Germany, where he spent a year at the Geophysical Institute of the University of Leipzig , with which the Bergen School maintained a lively exchange. There he received further training in handling aerological measurement data that has not yet been used directly in Bergen. Rossby spent most of the year at the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory in Brandenburg, where the upper layers of the air were explored with kites and balloons. After another summer stay in Bergen in 1922, he published his first scientific publication "Den nordiska aerologiens arbetsuppgifter" ("Tasks of Nordic aerology"), in which he proposed a network of stations for researching the upper air layers on the North Sea .

Then Rossby returned to Stockholm, where he studied mathematical physics at the university and in 1925 obtained a licentiate ( filosofie licentiat ) with a thesis examined by Erik Ivar Fredholm . To finance his studies, he worked for three years as a meteorologist for the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute . Rossby was also a participant in three research expeditions: in the summer of 1923 with the Conrad Holmboe to Jan Mayen and Greenland , in 1924 with the af Chapman around the British Isles and in 1925 with the same ship to Portugal and Madeira . At least on his second expedition, Rossby also carried out his own measurements of the upper air layers in addition to the weather forecasts.

Arrived in the United States (1926–1928)

For 1926, Rossby received a grant from the American-Scandinavian Foundation to "research problems in dynamic meteorology" at the US Weather Bureau in Washington, DC . One of Rossby's goals was to show the applicability of polar front theory to American weather. However, the US weather department was still opposed to the new methods and Rossby's task of simulating the dynamics in the atmosphere with a rotating water tank initially failed. He then devoted himself to theoretical work on atmospheric turbulence.

In Washington, Rossby met the businessman Harry F. Guggenheim through his colleague Francis Reichelderfer , who had already dealt with the methods of the Bergen School himself . From 1926 he built up the "Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics" with 2.5 million dollars, in order to help US aviation to a leading position worldwide. Rossby commissioned Guggenheim to compile weather reports for Richard E. Byrd and Charles Lindbergh's flights . Although Rossby had fallen out with the head of the US Weather Bureau, Charles Marvin , about the weather report for the Lindbergh flight from Washington to Mexico City , he later proposed him with a letter of recommendation for a position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

After Rossby's scholarship expired, he focused on working with the Guggenheim Fund. In 1927 he was appointed chairman of the “Guggenheim Interdepartmental Committee on Aeronautical Meteorology”, which brought together scientists from various institutions and, among other things, was supposed to promote mutual understanding between meteorologists and pilots. Rossby's biggest project for the Guggenheim Fund was managing the weather service for the "Model Airway" in California. On the flight route between Los Angeles and San Francisco , small-scale forecasts were made from the population with the help of weather observations in order to make civil aviation possible on the route. Rossby recruited the weather observers along the route himself. Previously, the pilots had mostly relied on the current weather at the destination and their experience in the open cockpit.

Activity at MIT (1928–1939)

On the recommendation of Marvin and the initiative of MIT President Samuel Wesley Stratton , who raised funds for the Guggenheim Fund, Rossby took up a position as Associate Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on September 7, 1928 . In his first year he gave a lecture on dynamic meteorology and fluid mechanics as well as a seminar on current meteorological publications, submitted applications for a network of 20 meteorological stations in the northeastern USA and for research flights with meteorological instruments and initiated collaborations with Harvard and Blue Hill . Due to the large number of applications, Stratton even felt compelled in a letter to Rossby to curb his thirst for action: They fully support the development of the meteorological work, but are "not able to do this so quickly".

In Boston , Rossby met the aspiring gym teacher Harriet Marshall Alexander, whom he married in the fall of 1929. She left her job in Pennsylvania when she was expecting her first child in 1931. In total, the couple had two sons and a daughter: Stig Arvid (1931–2013), Thomas (* 1937) and Carin (1940–1971). Thomas Rossby later followed a career path similar to that of his father and is professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island .

In the summer of 1930 Rossby undertook a long trip through Europe, which took him to several German cities as well as to Vienna , Bergen and Stockholm. In Stockholm he took part in the General Assembly of the International Union for Geodesy and Geophysics . On the trip, Rossby dealt among other things with how the “gap” between the Austrian-German school around Felix Exner-Ewarten and the Bergen school can be “healed”. In 1931 Rossby became a full professor at MIT and a researcher at the new Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution . With Henry Bryant Bigelow he set up a cooperation program between MIT and Woods Hole on the dynamics of the ocean and atmosphere.

In the mid-1930s, Rossby at MIT was already "on the way to establishing a new school of meteorology". This mainly concerned his theoretical contributions to atmospheric thermodynamics and fluid dynamics in the atmosphere and ocean. Rossby's group at MIT was also one of the customers of the first commercial radiosondes for Finnish entrepreneur Vilho Väisälä in 1936 .

Intermezzo at the US Weather Bureau (1939–1941)

Even after Reichelderfer became head of the US Weather Bureau in 1938, the transformation to the forecasting methods of the Bergen School was not yet complete. Rossby complained that "too many of the well-meaning old hands are in power" there. He therefore agreed to work for three years as the deputy head of the weather service with responsibility for research and education.

He took up his post in Washington on July 1, 1939 and "immediately regretted the decision." He felt that his scientific work was restricted mainly by bureaucracy and responsibility for training programs. In a letter to MIT President Karl Taylor Compton , Rossby expressed his desire to resign from his post by the end of January 1940 at the latest and take a sabbatical or receive a research professorship at MIT. This ultimately failed due to the lack of funding, so he initially stayed in the service of the US Weather Service. There he coordinated, among other things, three-month crash courses for up to 180 employees of the weather service per year.

During his time at the Weather Bureau, Rossby published several scientific articles on the previous research results of his working group at MIT, including the 50-page paper "The Scientific Basis of Modern Meteorology".

Chicago and World War II (1941–1947)

In 1940 a new institute for meteorology was founded at the University of Chicago on the initiative of Rossby's former student Horace Byers , of which Rossby became the first director. He was first given a year off leave to continue his work with the US Weather Service before taking up his position in Chicago in 1941. In the same year the United States entered World War II . The following years were therefore dominated by the training of thousands of military meteorologists in programs in the Army , Navy and universities, coordinated by Rossby .

In addition to academic work, Rossby was an advisor to the Office of the Secretary of War and the Commanding General of the US Army Air Forces during World War II . In the course of this activity he made numerous trips to the war zones, including Guam , Morocco and the Soviet Union . In addition, on Rossby's initiative in 1943, in cooperation with the military, the Institute for Tropical Meteorology at the University of Puerto Rico was founded, which investigated atmospheric dynamics away from the influence of the polar front.

The fact that the officers in the military weather service had mostly only been trained for nine months and had no scientific experience, Rossby saw only as a compromise for the war. As early as the Second World War, he therefore strived for greater cooperation between the military and universities, including involving more civilian scientific personnel in military meteorological research. On the other hand, the Graduate School in Chicago , run by Rossby, received most of its funding from the military. Even after the war ended, Rossby maintained his "considerable" contacts with the US military. Among other things, he initiated that the IAS computer project led by John von Neumann and financed by the Office of Naval Research was also used for numerical weather forecasting .

From 1944 to 1945 Rossby served for two years as President of the American Meteorological Society , within which he undertook a major restructuring from an amateur to a professional scientific society . In this role he was also the founder and one of the first authors of the Journal of Meteorology . At the University of Chicago, Rossby also recruited some leading European meteorologists such as Erik Palmén during this time . He initiated new hydrodynamic experiments with a rotating water tank and made first theoretical considerations on numerical weather forecast. By the end of his time in Chicago, Rossby had already established a "Chicago School of Meteorology".

Return to Stockholm (1947–1957)

In early 1946, the physicist Harald Norinder, who advised the Swedish government on improving meteorological training and research, and the glaciologist Hans Ahlmann officially proposed that the government bring Rossby to Sweden. Rossby then met with Education Minister Tage Erlander , who offered him a position at Stockholm University. When he left Chicago for Stockholm in September 1947, he was initially only on leave of absence from the University of Chicago and held his research professorship there until 1951. In his contemporaries' view, his return to Sweden was primarily due to his “love for his homeland” new challenge of the development of meteorology and oceanography in Europe and the increasing internationalization of his work. However, due to bureaucratic hurdles in particular, Rossby found the meteorological research landscape in the USA “no longer [...] very stimulating”.

In Stockholm, Rossby worked at the SMHI and the university in parallel . Soon after his arrival he founded the geophysical journal Tellus , which explicitly published non-meteorological articles. Rossby continued to finance his work mainly with US funds, which he said accounted for two-thirds of his funding in 1957. A “considerable” part of this money came from military sources, most of which came indirectly to Rossby's institute due to the Swedish policy of neutrality . He also maintained close scientific contacts in the USA. In addition to a lively correspondence, he received numerous visitors in Sweden and traveled to Chicago and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution for longer research stays, with which he remained associated until the end of his life. His confidante Bert Bolin , who frequently represented him in Stockholm in the 1950s, later wrote: “He was just as busy with the development of US meteorology as with the start on the European side of the Atlantic.” However, he declined offers for a permanent return to America from Chicago, from MIT and from John von Neumann and Jule Charney from the Institute for Advanced Study .

Rossby made contacts in numerous European countries and saw “diversity and international cooperation as fundamental elements for [scientific] progress”. In 1949 he visited Hans Ertel and was also interested in initiating contacts with the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin .

In Stockholm Rossby devoted himself to two new problems: the numerical weather forecast using the first Swedish electronic computer BESK and, from 1952, the global geochemical transport processes in the atmosphere. After Rossby's attempt to have the Institute of Meteorology in Stockholm recognized by UNESCO as an international research center, the Swedish Parliament in 1955 approved the establishment of the "International Meteorological Institute". His institute was from now on funded directly by the Swedish government, but was still closely linked to the university.

On August 19, 1957, Carl-Gustaf Rossby died unexpectedly at the age of 59 in his Stockholm office of a heart attack caused by his chronic heart disease . Until shortly before his death he was involved in the organization of the International Geophysical Year 1957/58, which also focused on his current research areas. His last 40-page article, “Current Problems in Meteorology”, in which he summarized the status of his research in Stockholm, was published posthumously in 1959 in English.

Scientific work

Further development of the methods of the Bergen School

In his first years in the USA, Rossby was mainly concerned with the further development of the methods of the Bergen School and their application to the North American continent. Discontinuities in air pressure , temperature and wind , later referred to as " fronts ", played a central role in the Bergen School , with the location of the polar front playing the greatest role in Norway . In one of his first work at the US Weather Bureau, Rossby tried to show the influence of the polar front on the weather in the United States, which Anne Louise Beck and Jacob Bjerknes had already tried in previous years . During the year he published two articles on this in the Monthly Weather Review . With his co-author Richard Weightman he believed to have provided "conclusive evidence" that "the polar front theory can be applied to the United States with great advantage [...]".

From 1929 onwards, Rossby's group at MIT examined and classified the American air masses , with a particular interest in their vertical structure. To do this, they used aerological data from successive ascents of a research aircraft and later from radiosondes. Rossby succeeded in identifying the air masses with the help of conservation quantities such as specific humidity and potential temperature . He developed the Rossby diagram, in which the potential temperature is plotted against the mixing ratio . Rossby and his students also developed the isentropic analysis, in which the atmospheric dynamics is observed not on surfaces of constant air pressure but of constant potential temperature.

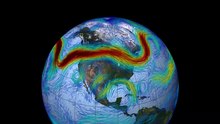

Rossby waves

From the mid-1930s onwards, Rossby's group began to focus more on the global atmospheric circulation. This was also made possible thanks to the new radiosondes, which enabled reliable measurements of the upper air layers beyond the 500 millibar level (about five kilometers above sea level). In 1935, Rossby also started a long-term weather forecast project at MIT. This allowed a statistical evaluation of frequent locations of high and low pressure areas, which in turn could be related to the measurements of the upper air layers.

In August 1939, Rossby published his theoretical treatise on global atmospheric circulation for the first time, which he placed in the tradition of geophysical hydrodynamics. His best-known result was the formula for the phase velocity of the planetary waves in the upper atmosphere, now known as Rossby waves :

where the phase velocity, the mean flow velocity in east-west direction, the Rossby parameter or beta parameter (see Rossby wave # mathematical description ) and the wavelength . It is noteworthy that Rossby "always used the simplest possible geometry" and thus formulated this formula in Cartesian instead of spherical coordinates .

Bernhard Haurwitz supplied the latter variant a year later, who also made parallels with his own work from 1937, which in turn was based on the ideas of Max Margules and Sydney Samuel Hough from the 1890s. In 1945 Rossby introduced the group speed for planetary waves, which plays an important role in energy transport.

Potential vorticity

Rossby often used hydrodynamic conservation quantities in his work, especially vorticity . Building on Vilhelm Bjerknes' vertebral theorem, which generalized the Helmholtz and Kelvinian vertebral theorems, Rossby developed the term for the conservation quantity potential vorticity in 1940 . It indicates the absolute circulation per mass for an adiabatic , frictionless flow. Rossby showed this as early as 1936 as part of his oceanographic work on the Gulf Stream for a hydrostatic fluid with a small vertical extent, and two years later for a fluid with discrete layers.

Rossby's colleague Hans Ertel, who had visited MIT and the Blue Hill Observatory for two months in 1937, published a clearly generalized version of the conservation law in 1942. That he knew of Rossby's work at this point is considered likely, but not certain, as he did not quote him. Rossby's visit to Berlin in 1949 resulted in two joint articles by Rossby and Ertel, in which they proved and discussed their discovery.

Reception and aftermath

Tor Bergeron wrote shortly after Rossby's death: "Before him [Rossby], no single scientist with his work and personality seems to have had so much influence on the meteorology of his time." Rossby had both as a scientist who was primarily devoted to theoretical research , as well as an organizer, had a great influence on the development of meteorology. The science historian James Fleming also describes him as “probably the most influential and innovative meteorologist of the 20th century”.

Rossby founded major meteorological research institutes at MIT, the University of Chicago and Stockholm University, where his research was often carried out by his own students. His total of 23 doctoral students included Chaim L. Pekeris , Horace Byers, Harry Wexler , Reid Bryson , Joanne Malkus Simpson and Bert Bolin, who co-founded the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1988 . A study in 1992 concluded that "[Rossbys] protégé (and their protégés) undoubtedly significant positions in teaching, research and administrative world" held to have. His influence extends over the USA and Western Europe to China. Rossby was considered both a good "talent count" and a scientist who intuitively recognized and promoted meaningful ideas. Regarding Rossby's personality, his charm and persuasiveness were repeatedly emphasized.

The isentropic analysis introduced by Rossby and its use of physical conservation quantities can be seen as the cornerstone of today's mesoscale meteorology , which deals with atmospheric processes between 2 and 2000 km. His scientific work on planetary waves initially influenced synoptic meteorology , within which the prediction of long waves was already established as routine at the end of the 1940s. Today, atmospheric Rossby waves play an important role in weather and climate research. In oceanography, too, they are part of all modern theories of large-scale ocean circulation , even if they have only been reliably demonstrated experimentally since the mid-1990s.

Towards the end of his time in Stockholm, Rossby turned to global ecological issues. The phenomenon of acid rain in Sweden was described for the first time in a study on the pH value of rain, which was supported by his institute . Rossby also commented on the "possibility of [...] human influence [...] on the earth's surface climate" through CO 2 emissions in his last scientific article. As part of the preparation of the International Geophysical Year, he was also part of the discussions about establishing long-term CO 2 measurements in Hawaii, from which the Keeling curve emerged .

Honors

Rossby was awarded honorary doctorates by two universities, Kenyon College in the US state of Ohio (1939) and Stockholm University (1951) . In addition, he was a member of numerous scientific societies. In the USA he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1934 , to the National Academy of Sciences in 1943 and to the American Philosophical Society in 1946 . In 1955 he was elected a member of the Leopoldina . He was also a member of the Austrian , Finnish , Norwegian and Royal Swedish Academies of Sciences, the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering and an honorary member of the Royal Meteorological Society .

The Royal Meteorological Society awarded Rossby the Symons Gold Medal in 1953, one of the two highest honors the organization bestows. In the same year he received the Award for Extraordinary Scientific Achievement from the American Meteorological Society, which was renamed the Carl-Gustaf Rossby Research Medal in his honor after Rossby's death . Rossby was also posthumously honored in 1957 with the International Meteorological Organization Prize of the World Meteorological Organization . The SMHI named the Rossby Center in Norrköping after him, which conducts research into climate modeling . In addition, the Rossby crater in the Eridania Gradfeld has been named after him since 1973 .

Outside the scientific world, Look magazine included Rossby in its list of the 100 Most Influential People in the World in the fall of 1955. The Time Magazine praised Rossbys contributions to meteorologist with an extensive article in the issue of December 17, 1956 he was also displayed on the front cover.

Publications (selection)

For a full list of Rossby's publications, see the National Academy of Sciences overview.

- The Nordiska aerologiens arbetsuppgifter. A closer look and other program . In: Ymer . tape 43 , 1923, pp. 364-376 .

- with Richard H. Weightman: Application of the polar-front theory to a series of American weather maps . In: Monthly Weather Review . tape 54 , no. December 12 , 1926, p. 485-496 , doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0493 (1926) 54 <485: AOTPTT> 2.0.CO; 2 .

- Thermodynamics Applied to Air Mass Analysis . In: MIT Papers in Physical Oceanography and Meteorology . tape 1 , no. 3 , 1932, doi : 10.1575 / 1912/1139 ( mblwhoilibrary.org [PDF]).

- with Raymond B. Montgomery: The layer of frictional influence in wind and ocean currents . In: Papers in Physical Oceanography and Meteorology . tape 3 , no. 3 , April 1935, doi : 10.1575 / 1912/1157 ( mblwhoilibrary.org [PDF]).

- Dynamics of steady ocean currents in the light of experimental fluid dynamics . In: Papers in Physical Oceanography and Meteorology . tape 5 , no. 1 , 1936, pp. 1-41 , doi : 10.1575 / 1912/1088 ( o3d.org [PDF]).

- On the mutual adjustment of pressure and velocity distributions in certain simple current systems, II . In: Journal of Marine Research . tape 1 , no. 3 , 1938, pp. 239-263 ( yale.edu [PDF]).

- with employees: Relation between variations in the intensity of the zonal circulation of the atmosphere and the displacements of the semi-permanent centers of action . In: Journal of Marine Research . tape 2 , no. 1 , 1939, p. 38-55 ( yale.edu [PDF]).

- Planetary flow patterns in the atmosphere . In: Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society (supplement) . tape 66 , 1940, pp. 68-87 ( ex.ac.uk [PDF]).

- The Scientific Basis of Modern Meteorology . In: US Department of Agriculture (Ed.): Yearbook of Agriculture . 1941, p. 599-655 ( usda.gov [PDF]).

- On the propagation of frequencies and energy in certain types of oceanic and atmospheric waves . In: Journal of Meteorology . tape 2 , no. 4 , 1945, p. 187-204 , doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0469 (1945) 002 <0187: OTPOFA> 2.0.CO; 2 .

- On the Distribution of Angular Velocity in Gaseous Envelopes Under the Influence of Large-Scale Horizontal Mixing Processes . In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society . tape 28 , no. 2 , 1947, p. 53-68 , doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0477-28.2.53 .

- with Hans Ertel : A New Conservation Theorem of Hydrodynamics . In: Geofisica pura e applicata . tape 14 , 1949, pp. 189-193 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01981973 ( psu.edu [PDF]).

- Current Problems in Meteorology . In: Bert Bolin (Ed.): The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion. Scientific Contributions to the Rossby Memorial Volume . The Rockefeller Institute Press, New York 1959, pp. 9-50 .

literature

- James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology . MIT Press, Cambridge 2016, ISBN 978-0-262-03394-7 , pp. 77-128 .

- James R. Fleming: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: Theorist, institution builder, bon vivant , Physics Today, Volume 70, January 2017, pp. 51-56

- Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898–1957. A Biographical Memoir . National Academy of Sciences , Washington, DC 1960 ( nasonline.org [PDF]).

- Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby . Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering, Stockholm 2015, ISBN 978-91-7082-903-1 ( iva.se [PDF]).

- Tor Bergeron: The Young Carl-Gustaf Rossby . In: Bert Bolin (Ed.): The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion. Scientific Contributions to the Rossby Memorial Volume . The Rockefeller Institute Press, New York 1959, pp. 51-55 .

- Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947–1957 . In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology . tape 51 , no. 1 , 2016, p. 4–12 , doi : 10.3402 / tellusb.v51i1.16255 .

- Norman A. Phillips: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: His Times, Personality, and Actions . In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society . tape 79 , no. 6 , 1998, pp. 1097-1112 , doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0477 (1998) 079 <1097: CGRHTP> 2.0.CO; 2 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898-1957. A Biographical Memoir , p. 249.

- ^ Tor Bergeron: The Young Carl-Gustaf Rossby. In: Bert Bolin (Ed.): The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion , p. 51.

- ^ A b Tor Bergeron: The Young Carl-Gustaf Rossby. In: Bert Bolin (Ed.): The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion , p. 52.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby , p. 14

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 78.

- ^ GH Liljequist: Tor Bergeron. A biography. In: Pure and Applied Geophysics. 119, 1981, p. 413, doi : 10.1007 / BF00878151 .

- ↑ a b James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 79.

- ^ Tor Bergeron: The Young Carl-Gustaf Rossby. In: Bert Bolin (Ed.): The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion , p. 53.

- ^ A b Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898-1957. A Biographical Memoir , p. 251.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 80.

- ^ Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898-1957. A Biographical Memoir , p. 252.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 81.

- ^ A b David Laskin: The Weatherman and the Millionaire. In: Weatherwise. July / August 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ a b James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 84.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 87.

- ↑ a b James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 90.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby f, p. 24

- ↑ Dr. Rossby. Discovery of Sound in the Sea, accessed September 29, 2019.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 93.

- ^ A b Norman A. Phillips: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: His Times, Personality, and Actions. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Volume 79, No. 6, p. 1103.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby , p. 25

- ↑ a b James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 100.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 101.

- ^ Douglas R. Allen: The Genesis of Meteorology at the University of Chicago. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 82, 2001, p. 1907, doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0477 (2001) 082 <1905: TGOMAT> 2.3.CO; 2 .

- ↑ a b James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 107.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 108.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby , p. 30

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 110.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: Narrative and counter-narrative of climate change: North Atlantic glaciology and meteorology, c.1930-1955. In: Journal of Historical Geography. 35, 2009, p. 248, doi : 10.1016 / j.jhg.2008.09.003 .

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: Narrative and counter-narrative of climate change , S. 250th

- ^ Norman A. Phillips: Jule Gregory Charney 1917-1981. A Biographical Memoir . National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC 1995, pp. 88-92 ( nasonline.org [PDF]).

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 111.

- ^ Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898-1957. A Biographical Memoir , p. 259.

- ^ Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947-1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 6.

- ^ About the Department. The Department of Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, archived from the original on May 14, 2005 ; accessed on September 29, 2019 .

- ^ Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947-1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 5.

- ↑ a b Sverker Sörlin: Narratives and counter-narratives of climate change , p. 251.

- ^ Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947-1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 4 f.

- ↑ HC Willett: C.-G. Rossby, Leader of Modern Meteorology. In: Science. 127, 1958, p. 687, doi : 10.1126 / science.127.3300.686 .

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 118.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby , p. 44

- ^ Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947-1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 6.

- ^ A b Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947–1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 7.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 122.

- ^ Norman A. Phillips: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: His Times, Personality, and Actions. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Volume 79, No. 6, pp. 1106 f.

- ^ Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947-1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 8.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 126.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 81.

- ^ Carl-Gustaf Rossby and Richard H. Weightman: Application of the polar-front theory to a series of American weather maps. In: Monthly Weather Review. Volume 54, No. 12, December 1926, p. 496.

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 89.

- ↑ Jerome Namias : The early influence of the Bergen School on synoptic meteorology in the United States. In: Pure and Applied Geophysics. 119, 1981, p. 496, doi : 10.1007 / BF00878154 .

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 91.

- ^ GW Platzman: The Rossby wave. In: Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 94, 1968, pp. 225 f., Doi : 10.1002 / qj.49709440102 .

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 103.

- ^ Norman A. Phillips: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: His Times, Personality, and Actions. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Volume 79, No. 6, p. 1104.

- ^ Alan J. Thorpe, Hans Volkert and Michał J. Ziemiański: The Bjerknes' Circulation Theorem: A Historical Perspective. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 84, 2003, p. 473, doi : 10.1175 / BAMS-84-4-471 .

- ^ Alan J. Thorpe, Hans Volkert and Michał J. Ziemiański: The Bjerknes' Circulation Theorem: A Historical Perspective. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 84, p. 478.

- ^ Geoff Vallis: Classic and Historical Papers Papers on Geophysical Fluid Dynamics. , Department of Mathematics, University of Exeter , accessed September 29, 2019.

- ↑ RM Samelson: Rossby, Ertel and potential vorticity. , October 10, 2003, accessed on September 29, 2019 (PDF; 83 kB).

- ^ Norman A. Phillips: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: His Times, Personality, and Actions. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Volume 79, No. 6, p. 1109.

- ↑ James R. Fleming: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: Theorist, institution builder, bon vivant. In: Physics Today. 70, 2017, p. 51, doi : 10.1063 / PT.3.3428 .

- ^ John M. Lewis: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: A Study in Mentorship. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 73, 1992, p. 1436, doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0477 (1992) 073 <1425: CGRASI> 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ^ John M. Lewis: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: A Study in Mentorship. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 73, p. 1437.

- ^ Bert Bolin: Carl-Gustaf Rossby The stockholm period 1947-1957. In: Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. Volume 51, No. 1, p. 11.

- ^ Norman A. Phillips: Carl-Gustaf Rossby: His Times, Personality, and Actions. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Volume 79, No. 6, pp. 1105 f.

- ^ Robert Gall and Melvyn Shapiro: The Influence of Carl — Gustaf Rossby on Mesoscale Weather Prediction and an Outlook for the Future. In: Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 81, 2000, pp. 1507f., Doi : 10.1175 / 1520-0477 (2000) 081 <1507: TIOCGR> 2.3.CO; 2 .

- ^ GW Platzman: The Rossby wave. In: Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 94, p. 227.

- ↑ DB Chelton, MG Schlax: Global Observations of Oceanic Rossby Waves. In: Science. 272, 1996, p. 234, doi : 10.1126 / science.272.5259.234 .

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming: Inventing Atmospheric Science. Bjerknes, Rossby, Wexler, and the Foundations of Modern Meteorology , p. 123.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby , p. 10

- ^ Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898-1957. A Biographical Memoir , p. 263.

- ^ About the Rossby Center. SMHI, September 1, 2011, accessed September 29, 2019.

- ↑ Rossby. In: Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. International Astronomical Union , November 17, 2010, accessed September 29, 2019.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin: A Tribute to the Memory of Carl-Gustaf Rossby , S. 64th

- ^ Science: Man's Milieu. Time Magazine, December 17, 1956, accessed September 29, 2019.

- ^ Horace B. Byers: Carl-Gustaf Rossby 1898-1957. A Biographical Memoir , pp. 265-270.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rossby, Carl-Gustaf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rossby, Carl-Gustaf Arvid |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swedish-American meteorologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 28, 1898 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stockholm |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 19, 1957 |

| Place of death | Stockholm |