Hammer Park

| Hammer Park | ||

|---|---|---|

| Park in Hamburg | ||

|

||

| View from the "vineyard" to the pond and stadium | ||

| Basic data | ||

| place | Hamburg | |

| District | Hamburg-Hamm | |

| Created | 1773 | |

| Newly designed | 1914 | |

| Surrounding streets | Hammer Steindamm, Sievekingsallee, Fahrenkamp, Caspar-Voght-Straße, Hammer Hof | |

| Technical specifications | ||

| Parking area | 16 ha | |

|

53 ° 33 '30 " N , 10 ° 3' 29" E

|

||

The Hammer Park is under monument protection standing public park in the district of Hamm in the east of Hamburg . In its current size and shape, it was designed between 1914 and 1920 by the Hamburg horticultural director Otto Linne . However, it goes back to an older and much larger private landscape garden, whose roots go back to the 17th century.

location

Hammer Park is about five kilometers east of Hamburg city center. Its area extends over almost 16 hectares and is framed by the streets Hammer Steindamm in the west, Sievekingsallee and Fahrenkamp in the north, Caspar-Voght-Straße in the east and Hammer Hof in the south. The latter is reminiscent of the site's previous name. The park is connected to local public transport through Hasselbrook train station in the north, Hammer Kirche underground station in the south and bus routes 116 and 261.

history

A plot of land called Hammer Hof northeast of the old Hammer village center has been proven since the middle of the 17th century at the latest. In 1690 it came into the possession of the Hamburg citizen Peter Burmester, who, along with other wealthy country house owners in the area, was one of the founders of the Hammer Dreifaltigkeitskirche .

The "Chapeaurougenhof" (1773 to 1829)

In 1773 the merchant Jaques de Chapeaurouge from Geneva bought the Hammer Hof and had a garden with a country house laid out there. At the time, it was located on the southwest corner of what would later become the park or on the site of today's stadium. Little by little, de Chapeaurouge bought the surrounding land and began to create a landscaped garden in the English style with ponds, grottos and artificial hills. In a contemporary description of the "Chapeaurougenhof" it says:

“Among the gardens of Hamburg garden lovers in this area, that of Mr. Chapeaurouge (...) is one of the most excellent. We hiked through it with great pleasure, since it is left open to public inspection by the humane owner. Much has succeeded in these gardens: the various types of trees and bushes are used with understanding; (...) Comfortable paths wander through these shady, lovely spots without compulsion and wind their way over wide lawns and past artificial flower beds. There an artificial spring invites you to enjoy the coolness (...). More out of the way, there is an artificial height, a small mountain on which narrow paths wind up between spruce and fir trees. (...) and many other places in this beautiful garden have been dear to me. "

In the winter of 1813/14 the park was largely destroyed by French occupation troops in order to create a clear field of fire against the advancing Russians under General Tettenborn . After the French left, Jean-Dauphin de Chapeaurouge , who had meanwhile taken over the farm from his father, had a new country house built at a new location further east on Fahrenkamp.

The Sievekingsche Hof (1829 to 1914)

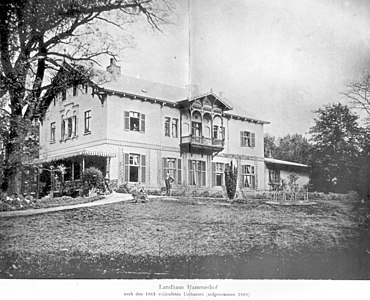

After de Chapeaurouge's death, his son-in-law, the Hamburg Senate Syndicus Karl Sieveking (1787–1847), acquired the property in 1829 and redesigned it into an ornamental farm based on the example of his godfather Caspar Voght and his Flottbeker country estate . For this purpose he had a brewery and a grain distillery built by his friend, architect Alexis de Chateauneuf , as well as a dairy , a brickyard, cow and horse stables, several barns and a head gardener's house in the Swiss style . A tenant was commissioned with the management. In the new country house, which was also converted and expanded by de Chateauneuf, the syndicus, who was interested in many things, received numerous scholars, artists, diplomats and princes, including the Danish King Christian VIII , for whom an art exhibition was organized by the Hamburg Artists' Association from 1832 . The Rauhes Haus foundation in neighboring Horn was also established in 1833 after the theologian Johann Hinrich Wichern visited Sieveking, who gave him a piece of land with the house that gave him the name for his planned “children's rescue village”.

First development plans and purchase by the city

After Sieveking's death, the country house was temporarily rented out by the heirs, but from 1857 they were inhabited again. When the need for building land increased rapidly after the incorporation of Hamm in 1894, the family offered their entire property, which extended far beyond what is now the park to Horn and the border with Wandsbek , to the city of Hamburg for sale. The first plans envisaged a development with single houses and villas (as in neighboring Marienthal ) as well as a park, which, however, should be significantly smaller than the current park. After protests from the citizenry was eventually determined to be obtained Park to its present size and Sieveking family compensated in return in that instead on the remaining land were provided of cottages lucrative floor residential buildings whose construction from 1920 under the overall planning of chief architect Fritz Schumacher took place .

Park design by Otto Linne (1914–1943)

After years of negotiations with the city, the site finally became public property in 1914. By 1920, today's park, which only includes a small part of what was once Sieveking's property, was redesigned as a public park by horticultural director Otto Linne and equipped with sports and playgrounds as well as model allotments. The network of paths, the stadium and the "hedge garden" in the north-east of the park have been preserved as evidence of the Linnean planning.

The former mansion and its outbuildings initially served as a school building for the Kirchenpauer grammar school and later as a public restaurant. During the Allied bombing raids in July 1943 , it was destroyed, as were the barns and the head gardener's house in Swiss style.

Destruction and redesign after 1945

The rest of the park was also badly affected by the firestorm . At times, parts of the park were built with makeshift homes for bombed-out people, in their place later a house for young people , the horticultural area of the district office and a daycare center for the elderly were built. Other areas were leased to local residents as “ grave land” and were used to grow potatoes and vegetables.

After the war u. a. a roller and roller skating rink, two open-air chess fields and, in 1959, one of the first mini golf courses in northern Germany. In place of the destroyed mansion there was a thatched pavilion until 1966, and in the 1980s a wooden structure with a rain roof. Proposals to build a new garden bar or kiosk have not yet been implemented.

Today's shape and use

Terrain profile

The park is located in the Hammer Geest natural area , directly above the Geest slope to the Ice Age Elbe glacial valley . The soils therefore mainly consist of glacial meltwater sands , partly over boulder clay . The terrain modeling essentially follows the conditions found in 1914: The highest elevations are the vineyard in the northwest, the Veilchenberg in the east and a plateau-like elevation in the area of the former manor house (terrace and hedge garden).

The lowest point of the park is marked by a historical stream that has now dried up and divides the entire area into a rather hilly and tree-lined northeast part and a rather flat southwest part covered with meadows.

Flora and fauna

Around half of the park area is overgrown with historical old trees from the 17th to 19th centuries and mainly contains oak, beech, linden, birch, maple and hornbeam, but also some exotic trees such as magnolias and evergreen oaks. There are noticeably many so-called “ couples ”, that is, old trees with two or more trunks as a result of deforestation during the French era . The oldest tree is a linden tree on the edge of the sports stadium, the age of which is estimated by experts to be 400 to 600 years.

The other half of the park consists mainly of meadow areas that are used intensively by the population, especially in the summer months. Rare plant species such as B. the chess flower .

Numerous species of birds are native to the park, and herons and large birds of prey have also been observed at times. The local NABU group offers guided tours on a regular basis.

Waters

The park is traversed by an artificial stream that originally connected three bodies of water (today's park pond, children's paddling pool and “fountain garden” north of the playground). After the development of the surrounding streets, it was cut off from its natural water supply and has fallen dry since the 1930s. The originally natural “paddling pool” was lined up after the Second World War and is now artificially watered in the summer months. Another consequence of the water shortage is the hypertrophication of the last remaining park pond, which can often be observed in the summer months . This was originally about twice as large as it is today and had to be reduced in size when the adjacent sports stadium was built.

Sculptures

A few sculptures were added to the park under Linne. The female nude by Paul Hamann in the so-called roundabout in front of the former mansion dates from this time . Another figure by Hamann originally stood in the hedge garden. It was removed and probably destroyed during the Nazi era.

There is a memorial stone for the writer and educator Joachim Heinrich Campe near the children's playground . This stone originally stood in front of Campe's house and educational institution on Hammer Deich, later on Robinsonplatz in Hammerbrook . After the complete destruction of the residential area there in the Second World War, the stone was moved to its current location in 1951.

The bronze sculpture Eulenbaum by Kurt Bauer near the Hammer Steindamm / Sievekingsallee entrance dates from the 1960s . Even more recent are some sculptures that were made by inmates of the Fuhlsbüttel prison as part of an art project and are only partially available.

Scorpionfish spouting water at the paddling pool, they originally held the steel cables of the bridge to Gurlitt Island

"Sapere aude" by Ludwig Udovic, was created in 1985 as part of a project with inmates of the Fuhlsbüttel prison

Sports and leisure opportunities

In the park, a playground and soccer field, a paddling pool for children, sunbathing lawns, a herb garden, flower and hedge garden, a mini golf course , several table tennis tables and a garden chess set with two playing fields offer a variety of recreational opportunities.

The grounds of the park also include a football and athletics stadium , the so-called Hammer Park Stadium . It has a grandstand for 2000 spectators and was the venue for national competitions until the 1960s. Today it is home to the soccer clubs SV St. Georg and Hamm United FC as well as the American football team Hamburg Huskies . Furthermore, the athletics department of the Turnerbund Hamburg-Eilbeck (the former LG Hammer Park) trains there .

A tennis facility of the Hamburg gymnastics club from 1816 is adjacent to the sports stadium ; however, the SV St. Georg tennis courts on the opposite side of Hammer Steindamm are no longer part of the park area. Before the war, the tennis courts were on the east side of the park, at what is now the House of Youth, and were also used as an ice rink in winter .

literature

- Fritz Encke : The public green spaces in Hamburg. In: Die Gartenkunst , issue 1/1929, pp. 1–18 (for Hammer Park, pp. 7 ff.)

- Heinz Krause et al. (Red.): The Hammer Park between yesterday and today. (Hamm district archive, vol. 1), Hamburg 1988.

- Gunnar Wulf, Kerstin Rasmußen: The Hammer Park. Gem between bricks. (Hamm district archive, Vol. 6), Hamburg 1995 ISBN 3-9803705-3-4

- G. Herman Sieveking : The history of the Hammerhof , 3 vol. Hamburg 1898–1933.

- Holger Paschburg and others (arrangement): Hammer Park in Hamburg. Maintenance and development plan . Expert opinion on behalf of the Hamburg-Mitte district office, gardening and civil engineering department, Hamburg 2005.

Web links

- Information about Hammer Park on hamburg.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Heinz Krause et al. (Red.): The Hammer Park between yesterday and today. (Hamm district archive, volume 1), Hamburg 1988, p. 6 ff.

- ↑ Adolf Diersen: From the history of the hammer Dreifaltigkeitskirche. Holzminden 1957, p. 11.

- ↑ cit. in: GH Sieveking: The history of the Hammerhof , vol. 1, p. 107 f.

- ↑ a b Gunnar Wulf u. a. (Red.): The Hammer Park. Gem between bricks. (Stadtteilarchiv Hamm - Volume 6), Hamburg 1995, p. 13 ff.

- ↑ GH Sieveking: History of the Hammerhof Vol. 2, p. 155.

- ^ Message from the Senate to the citizenship dated May 20, 1914, printed in: Der Hammer Park. Gem between bricks ..., p. 21 ff.

- ↑ Ten years of Kirchenpauer-Realgymnasium, Rauhen Haus print shop, Hamburg 1924.

- ↑ a b Gunnar Wulf u. a .: The Hammer Park. Gem between bricks ... , p. 43 ff.

- ^ Holger Paschburg et al. (Arrangement): Hammer Park in Hamburg. Maintenance and development plan . Expert opinion on behalf of the district office Hamburg-Mitte, gardening and civil engineering department, Hamburg 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Holger Paschburg et al. (Arrangement): Hammer Park in Hamburg. Maintenance and development plan . Expert opinion on behalf of the district office Hamburg-Mitte, gardening and civil engineering department, Hamburg 2005, p. 15, 33.

- ↑ Gunnar Wulf among others: The Hammer Park. Gem between bricks ... , S, 46.

- ↑ Heinz Krause and others: The Hammer Park between yesterday and today ..., p. 45.

- ↑ Wulf / Rasmussen: The hammer park. Gem between bricks, p. 150 ff.

- ↑ Erich Andres: Death over Hamburg, Junius-Verlag Hamburg 2018, p. 92.

- ↑ Wulf / Rasmussen: The hammer park. Gem ..., p. 154 f.

- ↑ Krause: Hammer Park between yesterday and today, p. 36.

- ^ LG Hammer Park before the dissolution

- ↑ Wulf / Rasmußen, p. 90. See also the Linne park plans in 1914 and 1924.