Pandemic H1N1 2009/10

|

|

| Colored , electron microscope image of some influenza A / (H1N1) viruses (source: CDC ) | |

| Data | |

|---|---|

| alternative name | Swine flu |

| illness | Influenza |

| Pathogens | A / California / 7/2009 (H1N1) |

| origin | Veracruz, Mexico |

| Beginning | April 19, 2009 |

| The End | August 2010 |

| Affected countries | 155 |

| Deaths | 151 700 - 575 400 |

The global occurrence of influenza diseases was designated as the H1N1 2009/10 pandemic , which was genetically closely related to an influenza virus variant of subtype A (H1N1) ( A / California / 7/2009 (H1N1)) and others that were discovered in 2009 Subvariants). The disease was often referred to colloquially as swine flu , and official sources more commonly referred to as new flu . The virus subtype was first found in mid-April 2009 in two patients who were diagnosed independently in the USA at the end of March . A further search initially showed an accumulation of such cases of illness in Mexico and indications of the virus being spread across the national borders to the north.

At the end of April 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned of the risk of a pandemic . At the beginning of June 2009, the growing and persistent virus transmissions from person to person were classified as a pandemic by the WHO. However, the WHO announced in mid-May that the criteria for the declaration of a pandemic should be revised in view of the low pathogenicity of this H1N1 virus. The enormous amount of attention and the scope of the measures taken was due to the fact that an earlier H1N1 subtype had caused the influenza pandemic of 1918/19 (the Spanish flu ), which resulted in deaths of 20 to 50 million people.

In August 2010, the WHO declared the "swine flu" pandemic over. During the pandemic phase, cases of H1N1 infections had been confirmed in laboratories in a total of 214 states and overseas territories. A connection with laboratory-confirmed H1N1 infections is assumed in 18,449 deaths. A study that appeared in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2012 estimated deaths at 151,700 to 575,400 for the first year the virus circulated.

Discussion about common names

There is no agreement regarding the name of the pandemic described here or the corresponding disease . The term "swine flu" prevailed at least until November 2009, especially in the media. It was also used by scientific and political organizations. The name comes from the fact that the new H1N1 influenza variant is a mixed form ( reassortant ) of two influenza viruses, the so-called precursor viruses, both of which had previously circulated in pig populations; however, the new virus variant has never been isolated from pigs.

Against the colloquial term "swine flu" has been argued, it runs the risk of confusion with a animal disease as that of the domestic pig occurring swine influenza ; this is caused by influenza viruses that circulate among pigs. Such virus variants can be the starting point for a reassortment of new variants that can also be transmitted to humans, but are not themselves causative agents of a disease in humans. The spread of the new H1N1 variant was also only detected from person to person, and there was no risk of infection when eating pork. Therefore, the terms "Mexican flu" or "North American flu" were occasionally used, which was based on earlier names for worldwide epidemics such as the Spanish flu (1918/1919) and the Hong Kong flu (1968/1970).

Finally, in official texts, next to the term “New Flu” (or “Novel Flu”), the term “Influenza A (H1N1) v” (where “v” stands for “variant”) or “Influenza A (H1N1) ) 2009 ” . In October 2011, her advisors recommended the World Health Organization to refer to the virus as "A (H1N1) pdm09" in the future .

Pathogen

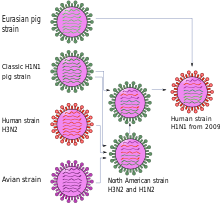

The first scientific publication described the new virus variant as a genetic new combination of two virus lines of swine influenza , one North American and one Eurasian, see quadruple combinants . The number of mutations between the new variant and the probable precursors contained in GenBank indicate that its gene segments had remained undiscovered for a long time. The low genetic diversity among the different virus isolates of the new variant and the fact that known molecular markers for adaptation to humans were not available suggested that the event of the transition to humans was not long ago. Antigenetically - this only applies to the gene segments for the proteins of the virus envelope - the viruses are homogeneous and resemble North American swine influenza viruses, but differ from viruses of the seasonal human influenza A (H1N1) .

This explained the results of a study of the immunity of the US population: the main finding was that the seasonal vaccine offered no or at least insufficient protection. However, it was also found that one third of the elderly population (over 60 years of age) had antibodies that were effective against the new variant. This in turn matched the observation that predominantly younger people fell ill, and was explained by the fact that there must have been an antigenically similar human virus around the middle of the last century.

The above work relativized the alarming statement of the first press conference of the US health authority Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that the new virus variant was also due to avian influenza viruses , which brought them close to the H5N1 pathogens considered dangerous (see also Influenza-A Virus H5N1 ). That wasn't entirely wrong, because birds are the natural reservoir of all influenza A viruses, but in this case none of the genetic components were directly related to birds. The originally represented origin from human A (H1N1) viruses was also corrected - it was based only on similarities to lines that had passed on to humans after their separation and had adapted independently to them.

According to a study published in 2016, the pandemic variant of the virus (pdmH1N1) originated in pigs in Mexico.

Epidemiology

In Mexico, health officials became aware of the start of the epidemic after an increase in pneumonia among younger people. According to the US health authority CDC , people between the ages of 30 and 44 were significantly more likely to suffer from severe courses than they were with seasonal influenza. According to initial calculations, the new virus variant was more contagious there, and the illness it triggered had a higher mortality rate than seasonal influenza: the mortality rate was around 0.4% (seasonal flu: 0.1%).

For the epidemic in Mexico, the base reproduction number was between 1.4 and 1.6, which means: 1 infected person infected 1.4 to 1.6 other people on average. Genetic comparisons of virus isolates from different regional origins are more representative, they resulted in a base reproduction number of 1.2 and also indicated a last common ancestor between November 2008 and January 2009.

Soon after the end of the pandemic phase, the virus variant discovered in 2009 and the illness it triggered was classified as significantly more harmless compared to other seasonal influenza variants and their consequences: the new variant even replaced other seasonal virus variants in the following years. As a result, as early as 2009, in areas where the H1N1 disease wave had passed and for which current data on the incidence of the disease were available in autumn 2009, there were considerably fewer deaths from influenza than in previous years. In Australia , for example, instead of the usual 2,000 to 3,000 deaths from seasonal influenza, there were only around 190 deaths and - as a result of the pandemic influenza - 189 other proven deaths. A noticeable difference between H1N1 deaths and deaths from seasonal flu was age: those who died from the "new flu" in Australia were on average 53 years old, those who died from seasonal flu 83 years.

prevention

World Health Organization pandemic planning

The World Health Organization had prepared a plan for the event of an influenza pandemic, on the basis of which the measures to be implemented nationally were to be coordinated on the basis of six pandemic phases . Phases 3 to 5 described the increasing risk of a pandemic, phase 6 stood for the global, increased and sustained spread, i.e. for an influenza pandemic in the narrower sense.

In April 2009 - as a reaction to the spread of the H5N1 avian flu and since 2006 - phase 3 ("alarm phase") was applied to influenza viruses, but given the dramatic development in Mexico, the WHO announced A (H1N1 ) phases 4 and 5 in quick succession. Already with the increase to phase 4, the Director General of the WHO, Margaret Chan , called on all countries to activate their pandemic emergency plans immediately. At the same time, the WHO advised against general travel restrictions, as this could no longer prevent the virus from spreading.

In response to the spread of the H5N1 avian flu , the World Health Organization made some changes to the definitions of the pandemic phases that had been discussed since 2007 - immediately before phase 4 and 5 were declared for virus A (H1N1). This included the definition of phase 6, which is now valid, that a pandemic is an “epidemic outbreak in at least two of the six WHO regions”; these regions are: Africa, North and South America, Southeast Asia, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific. Due to the newly enacted criteria for phases 4 to 6, which were mainly based on the extent of the spread, regardless of the possible consequences in terms of pathogenicity and lethality, level 6 should have been announced in May, as it was already in this month had come to H1N1 outbreaks in South and North America, Europe, Australia and Asia: The British Independent also quoted the virologist John Oxford, both in the United Kingdom and in Japan around 30,000 cases had remained undetected. In view of the low pathogenicity, however, the WHO hesitated until June 11, 2009 and at the same time announced that the criteria for the pandemic phases would be revised again.

quarantine

At the beginning of the epidemic, strict quarantine of suspected cases and infected people was the means of choice ( containment phase, 'containment'). From July 2009, another international strategy was pursued, which took into account that the spread of the virus could no longer be stopped: Therefore, the impact reduction strategy was followed, which provides preventive measures to reduce damage. Thereafter, only members of risk groups are admitted to inpatient care (two days are recommended, provided no complications arise), but other patients are immediately transferred to home care , where they should remain for a week. In Austria, for example, this regulation came into force at the beginning of August 2009, and a leaflet on how to carry out home quarantine contained explanatory notes .

vaccination

Vaccine preparation

The seasonal influenza vaccine planned for the 2009/2010 flu season was classified as not or only insufficiently effective against the new swine flu pathogen after appropriate studies. However, it was still produced because in the early summer of 2009 it was not yet foreseeable that the new pathogen would dominate the seasonal pathogens until the flu season.

Vaccination campaign

Since the spread of the swine flu pathogen could no longer be stopped and an adapted vaccine could probably not be produced for the entire population in time, the World Health Organization recommended in mid-July that all member countries give top priority to vaccinating the medical staff in order to be able to maintain the functionality of the health system . At the same time, it was left to the national authorities to give priority to vaccinating certain groups: children and adolescents who spread the virus quickly, or people under the age of 50 who have a lower natural immunity to this virus ( see above ), or special risk groups such as pregnant women, Small children from 6 months, older people or people with chronic respiratory diseases or very overweight.

Vaccines

In October 2009, four pandemic influenza vaccines were approved in the European Union :

| Surname | Manufacturer | Construction / extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Pandemrix | GlaxoSmithKline | made from fractions of viral envelopes from viruses bred in incubated hen's eggs (partial particle vaccine) with an enhancer |

| Focetria | Novartis | made from fractions of viral envelopes from viruses bred in incubated hen's eggs (partial particle vaccine) with an enhancer |

| Celvapan | Baxter | made from complete viral envelopes of viruses (inactivated whole-particle vaccine) grown in mammalian cells (Vero cells) without potentiators |

| Celtura | Novartis- Behring | made from fractions of virus envelopes of cell culture-based viruses (partial particle vaccine) with active enhancer |

National implementations

Germany

In Germany should up to 50 million people by 2009 flu vaccine against the new pathogens with the vaccine Pandemrix can be immunized. The Standing Committee on Vaccination of the Robert Koch Institute spoke of only one recommendation for vaccination for healthcare and welfare, the chronically ill and pregnant women on October 12 of 2009. The Standing Vaccination Commission pointed out, however, that vaccination can also benefit other population groups.

The vaccination campaign began in Germany on October 26th, 2009. It was slow in the first week, and even afterwards the willingness to vaccinate was largely low in Germany. In Germany the health authorities and resident doctors vaccinated in most cities and districts . Company doctors later also carried out this vaccination in some federal states.

The whole particle vaccine (whole virus vaccine) Celvapan should be used for members of the Bundeswehr and some federal authorities . Unlike Pandemrix , while Celvapan was free of controversial adjuvants like squalene and preservatives like thiomersal , it had a higher rate of undesirable side effects as a whole virus vaccine. Pure split vaccines without adjuvants were not used in Germany. In the United States, only adjuvant-free influenza vaccines were used.

On November 5, 2009, the Paul Ehrlich Institute approved the Celtura vaccine from Novartis-Behring. Like the other vaccines, Celtura only contained a single vaccine antigen and was therefore also a so-called monovalent vaccine.

At the beginning of May 2010, around 28.3 million of the 34 million vaccine doses procured in the German federal states were still unused. Negotiations with other states about a resale failed. The shelf life of the serum expired at the end of 2011, so it could no longer be used. For the federal states there was a loss of 239 million euros because the expired vaccine doses were not paid for by the health insurance companies.

Austria

The Austrian Federal Ministry of Health followed the Austrian Influenza Pandemic Plan , which included the provision of sufficient stocks of vaccines (ensuring a vaccine contingent for 8 million people), antiviral drugs ( neuraminidase inhibitors , for approx. 4 million people) and protective masks (approx 8 million available ad hoc). In Austria, up to 300,000 hospital employees were initially vaccinated from October 27th. Only “Celvapan” was used. The vaccination campaign for the general population began on November 9, 2009.

Switzerland

The Federal Office of Public Health ordered eight million cans of Pandemrix and five million cans of Focetria and Celtura in April 2009. The Swiss medicines authority Swissmedic approved these three vaccines on October 30 and November 13, 2009: Pandemrix (not for people under 18 years of age and pregnant women), Focetria (for children from six months and for adults) and Celtura for children from three years of age as well as for adults of all ages. These approvals differed from those of the EMEA in terms of indications for risk groups as well as in terms of approval duration. One reason was that Swissmedic was unable to exchange authorization data due to the lack of an agreement with the EMEA.

The organization of the vaccination campaign was the responsibility of the cantons and was therefore not uniform. From November 24, 2009 , the half-canton of Basel-Stadt made the vaccination available in medical practices as well as in hospitals and university institutes. The neighboring half-canton of Basel-Landschaft, on the other hand, vaccinated (in addition to the medical practices that continued to vaccinate) in five specially set up vaccination centers, which were open for six half-days between 19 and 28 November 2009. Of the 273,061 inhabitants of Basel-Land, 7,561 were vaccinated in the vaccination centers, the authorities expected 9,000 people to be vaccinated.

With the ordered 13 million vaccine doses worth 84 million Swiss francs, 6.5 million people, i.e. H. 80% of the population in Switzerland are vaccinated twice. Only in retrospect did it become apparent that one dose would have been enough for immunization. In addition, the "swine flu" did not spread as expected, and the willingness to vaccinate was far less than expected. In fact, 2.5 million doses were vaccinated. In January 2010, Switzerland signed a deal with Iran to sell 750,000 doses of the Celtura vaccine and gave it another 150,000 doses. Additional doses of Pandemrix vaccine were donated to the WHO. A total of 1.8 million Swiss vaccination doses were thus sold or given away. In 2010, 5.3 million cans of Celtura and Focetria were disposed of, and due to the expiry date in 2011, the remaining 3.4 million cans of Pandemrix.

diagnosis

Symptoms

The symptoms of the new variant did not differ from those of the annually recurring (“seasonal”) influenza waves (see the course of illness in influenza ); 1–2 days, but no more than 4 days, were specified for the incubation period . According to an assessment by the WHO on October 16, 2009, the virus variant caused mild disease courses without complications and with complete recovery in most cases. Worrying, however, was the severe and unknown course of seasonal influenza in a small number of cases, which led to intensive care requiring ventilation and to deaths, especially in younger age groups. Although the risk of a severe course was significantly increased, especially for certain groups of people, healthy young adults could also become very seriously ill.

Case definition: clinical and epidemiological criteria

Suspected, probable and confirmed cases of new influenza were defined by criteria that together formed the so-called case definition and were determined by the national health authorities, in Germany by the Robert Koch Institute. In it were initially

- the clinical picture ( acute respiratory illness with fever above 38 ° C or death due to unclear acute respiratory illness),

- the epidemiological exposure (by staying in an RKI- defined risk area outside Germany or by direct contact with a probable or confirmed case of illness or death or simultaneous stay in a room with a probable or confirmed case or stay in a clearly defined area with current outbreaks or by Working with samples in the laboratory) as well

- the laboratory diagnostic evidence (details below)

and thus determine the following case definitions:

- Suspected case: Person with a fulfilled clinical picture and the presence of epidemiological exposure as well as lack of evidence of another cause that fully explains the clinical picture.

- Probable case: person with laboratory diagnostic evidence of influenza A and a negative laboratory diagnostic result for the seasonal influenza subtypes A / H1 and A / H3.

- Confirmed case: person with laboratory diagnostic evidence of new influenza (A / H1N1) by (or in consultation with) the National Reference Center (NRZ) for influenza (then and currently the RKI itself).

In the current weekly reports of the RKI on the situation of influenza A (H1N1), the so-called reference definition was used as the basis for counting the reported cases. This is:

- "Clinical illness with laboratory diagnostic evidence or epidemiological confirmation."

In Germany, since May 3, 2009, in addition to the obligation to report a detected influenza infection under the Infection Protection Act (IfSG), there has also been an obligation to report suspected cases . Due to the rapid spread of swine flu, the reporting requirement was restricted. As of November 14, 2009, only patients had to be reported in whom the infection was clearly proven on the basis of laboratory tests, as well as deaths that were related to the swine flu.

In late April 2009, the World Health Organization had decided for the "new flu" the ICD-10 code to use J09, who previously was: "Influenza Caused by influenza viruses did normally infect only birds and, less Commonly, other animals" whose Wording should be adjusted accordingly. The current German definition of J09 is: "Influenza caused by zoonotic or pandemic proven influenza viruses" , whereby the following is explained: "For the use of this category, the guidelines of the WHO Global Influenza Program (GIP) must be observed."

Laboratory diagnostics

Most traditional diagnostic procedures for acute seasonal influenza infection can only detect general influenza A infection. The Robert Koch Institute and other specialized laboratories were also able to specifically and reliably detect the new variant of the H1N1 virus using an adapted method. This required a throat or nasal swab, which should be taken by a doctor in coordination with the local health department and forwarded to an appropriate laboratory for diagnosis.

As with any other virus infection, there are basically two options for virus detection in the laboratory: direct pathogen detection and indirect detection of specific antibodies . The latter is only possible after a period of time if two blood samples are compared, one at the time of the illness and another at least two weeks afterwards. A fourfold increase in the antibody titer is considered to be evidence of a past infection. Although this test procedure is part of the laboratory definition of the disease, it was not used because of the delay.

In the epidemiological situation of a spread, direct pathogen detection plays a central role. In the case of the new variant, antigens (virus proteins) of the virus could be detected in throat rinsing fluid, throat or nasal swabs with so-called influenza rapid tests. Rapid tests have a lower specificity and sensitivity than more complex virological methods, but can be carried out on site and in a few minutes. The rate of false negative results (sensitivity) for some rapid tests is up to 30 percent; false positive results (specificity) range between one and ten percent. The traditional rapid tests can only differentiate between influenza A and B. More modern rapid tests also differentiate between subtypes of influenza A and contributed to the first identification of the pathogen causing swine flu.

A reliable detection of the pathogen requires virus isolation, the “rewriting” of the viral RNA in cDNA and a subsequent PCR using virus-specific primers . The isolation of the new variant by cultivation in cell cultures (MDBK cells, English Madin-Darby bovine kidney : epithelial cells from bovine kidneys) or incubated chicken eggs was possible within one to two days; then the replicated virus was typed with various type-specific antibodies. This method is considered the reference method ("gold standard"). Evidence of the nucleic acid of the influenza virus by PCR is faster possible, but the established PCR method had to sequence comparisons with published genome sequences of the new variant compared to if they can also detect this variant. Most influenza virus PCR methods detect RNA sections of the genes of the matrix protein (M1 on segment 7) or nucleoprotein. However, they were initially unable to differentiate between normal A / H1N1 variants and the newly emerged variant. In various institutes, additional PCR methods have therefore been developed since the variant appeared, which allowed such a differentiation via the HA1 gene. For example, the WHO published the state of the art on May 21, 2009 and explicitly pointed out the need for internal and external quality assurance in laboratory diagnostics.

therapy

Diseases resulting from an infection with the new H1N1 virus variant were treated symptomatically like any other infection with influenza A or B: This included strict and long bed rest, increased fluid intake and paracetamol to reduce fever. The administration of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is avoided , especially in children, because of the possibility of Reye's syndrome caused by it in influenza . Complications from bacterial superinfections , which determine the severity of the disease in any influenza, are treated with antibiotics .

The virus variant proved to amantadine and rimantadine -resistant , but sensitive to the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) , while the seasonal variation of the A (H1N1) viruses to oseltamivir resistant, but not to amantadine, rimantadine and Zanamivir. Their oseltamivir resistance had spread in 2008. These antivirals are only effective if they are taken within 48 hours of the onset of flu symptoms. In this context it should be mentioned that, on the one hand, rapid tests in the early stages of the infection are often false negative, and on the other hand, in about half of all cases with this pathogen, coughs and hoarseness occurred one to two days earlier than the fever. This is why the European health authority ECDC recommended that the (prophylactic) administration of antivirals for patients and contact persons with existing risk factors should not be made dependent on laboratory results, but that clinical and epidemiological information should be sufficient.

According to the company headquarters of Hoffmann-La Roche in Basel and the Statens Serum Institute (SSI) in Denmark , resistance to oseltamivir in "swine flu" was observed for the first time in a patient receiving oseltamivir at the end of June 2009, which is why the patient was then treated with zanamivir. Up to August 2009, similar cases were reported from El Paso (Mexico / USA) as well as Canada, Japan and Hong Kong.

In the United States, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the newly developed additional neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir iv . However, the preparation was only allowed to be used for selected hospitalized children or adults who did not respond to oral or inhalative antiviral therapy.

Worldwide spread

As of October 25, 2009, more than 440,000 laboratory-confirmed infections with the H1N1-2009 virus had been reported to WHO worldwide, of which at least 5,700 were fatal. The laboratory-confirmed cases only represent part of the actual infections, because in many countries laboratory tests are only carried out in particularly severe cases. The spread in the United States has only been estimated since June 2009, at least one million cases at the time. At the beginning of July, the WHO also recommended that the mass tests of all suspected cases should be discontinued and instead that tests should only be carried out on a random basis in order to follow the development and discover changes in the virus.

As of January 31, 2010, the WHO reported at least 15,174 deaths. However, these were only the reported cases that have also been confirmed by laboratories. The actual number is significantly higher. The virus has now been detected in over 209 countries.

A study that appeared in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2012 estimated deaths at 151,700 to 575,400 for the first year the virus circulated.

In most of the southern hemisphere countries, the 2009 H1N1 virus variant was the dominant influenza virus in the 2009 season. In countries with a tropical climate, where the virus spread later than in other countries, an increase is to be expected. In the countries of the northern hemisphere, this variant has dominated since early summer 2009 and also in the 2009/2010 season, which was just beginning.

The clinical picture appears to be broadly similar in all countries. The vast majority of patients get sick only slightly. However, there are a small number of very serious and sometimes fatal courses, even in younger people who do not belong to high-risk groups.

Initial spread in North America

Mexico

At the beginning, in April 2009, diseases spread to the federal district of Mexico City as well as the states of Baja California , San Luis Potosí and Oaxaca . In press reports, significantly higher numbers were initially mentioned than by official circles. The initially very large difference in the number between confirmed cases and the press reports resulted from the fact that at the same time there was a seasonal flu epidemic in Mexico and the search for the new variant exceeded laboratory capacities.

The media has linked this outbreak to the novel cases of influenza in the United States. The Mexican health minister recommended that all schools across the country be closed and rules of conduct issued. Protective masks were distributed across the country.

On May 1, 2009, on the instructions of Mexican President Felipe Calderón, a five-day compulsory vacation began in Mexico City. Calderón pointed out that one's own home is the safest place to avoid infection.

From March to May 29, 2009, 5,337 people fell ill and 97 of them were fatal.

As of February 10, 2010, the Mexican Ministry of Health (Secretaría de Salud) had reported 70,453 confirmed illnesses, 1,035 of which were fatal.

United States

The CDC reported the first two cases of infection by a new human influenza A virus subtype H1N1 in the United States on April 21, 2009. These were two children in San Diego County and Imperial Counties , California , who died on April 28 , 2009 . and March 30, 2009. As of April 24, 2009, eight patients became ill, six of them in southern California. On April 29, 2009, the CDC confirmed the death of a 22-month-old Mexican child immigrated from Mexico in Texas.

At the end of April 2009, more than 400 schools were temporarily closed in the United States, and President Obama wrote a letter to Congress calling for US $ 1.5 billion in funding . The money will be used to replenish stocks of influenza drugs, develop new vaccines, monitor and diagnose other cases of the disease and support international efforts to limit virus transmission.

In the south and southwest of the United States, which had initially affected primarily - imposed on 27 April 2009 Governor Schwarzenegger to emergency California - went in summer the activity back while the virus spread further in the cooler north-east. New York was particularly hard hit: by June 2009, 6.9% of the population, half a million people, most of them within three weeks of May, and more than 20 died. Epidemiological estimates put at least one million cases across the country.

In May 2010, the CDC published a death estimate. According to her, between April 2009 and April 2010 there were at least 8,870 and a maximum of 18,300 deaths as a result of the H1N1 pandemic.

Spread in other regions

The World Health Organization published current information on the situation in various regions and countries on a dedicated website.

The development of the spread of the virus in Europe has been documented by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Reported cases in Germany

In Germany , the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) received a total of around 226,000 confirmed cases of the new flu and 250 attributable deaths from April 2009 to the beginning of May 2010 ; The pandemic also included around three million H1N1-related doctor consultations, around 5,300 hospital admissions and more than 1.5 million days of incapacity for work. The number of new infections had declined since December 2009; Vaccination was still recommended, however, as numerous other cases are to be expected even after the peak of an infection wave. At the end of February 2010, respiratory diseases were mostly caused by other pathogens causing acute respiratory diseases.

According to estimates, a total of 350 people died in Germany.

Spread in Austria

Around 4,000 infections with the pandemic H1N1 variant were registered in Austria, as well as 40 deaths that can be attributed to it. From November 11, 2009, the so-called “Mitigation Level 2” applied in Austria. According to this, only “laboratory-confirmed hospitalized cases of illness” and “deaths” had to be reported; in the case definition, stay in certain countries was no longer a criterion and the number of cases of illness was calculated by extrapolation.

Transfer to animals

A case in Canada showed that the pandemic variant of the H1N1 virus - like other H1N1 variants - can be transmitted from humans to domestic pigs . On May 2, 2009, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency classified the transmission of the virus from an infected man to a pig herd as highly likely. On May 4, 2009 , the President of the Friedrich Loeffler Institute demanded hygiene measures because it was still unclear how the new A (H1N1) variants behave in pigs. In such cases, there is a risk that viruses of different origins will combine again in pigs and thereby become more dangerous for humans, for example. In fact, numerous reassortments were reported in European domestic pigs in 2020. Researchers at the Friedrich Loeffler Institute were also able to scientifically prove that the virus was transmitted from sick pigs to healthy pigs by means of an experiment on the island of Riems .

The Chilean agricultural authority Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG) had, according to its own information, detected an infection with the pandemic variant in turkeys in the Chilean port city of Valparaíso .

Assessment of the pandemic

According to the WHO press release on January 22, 2010, the peak of the pandemic in the northern hemisphere was exceeded in December 2009 and January 2010. New infections were still widespread, but declined overall. In the second calendar week of 2010, fewer than 600 deaths had occurred worldwide.

On August 10, 2010, the WHO declared the pandemic to be over. The H1N1 influenza had entered a “post-pandemic phase”, and according to the WHO, increased outbreaks of the flu outside of the normal season were not observed. At the beginning of 2011, swine flu was declared a seasonal influenza in Austria.

In retrospect, it turned out that the diseases caused by the pandemic H1N1 variant were particularly mild. On the one hand, the pandemic variant had replaced all other influenza viruses circulating in the previous years in 2009/2010 and remained predominant in the winter half of 2010/2011. A statistical calculation of influenza-related excess mortality , which is carried out annually by the Robert Koch Institute for Germany, on the other hand, resulted in an excess mortality of zero for the 2009/2010 flu season and also for 2010/2011 ; For comparison: in the winter half of 2008/2009 the excess mortality was 18,700 people.

The coincidentally shortly before the start of the H1N1 outbreak as a response to the spread of the H5N1 avian flu, the WHO defined phase 6, namely that a pandemic is "epidemic outbreaks in at least two of the six WHO regions", has been in place since WHO guidelines for Pandemic Influenza Risk Management valid in 2013 and revised again in 2017 are no longer included. The trigger for the renewed changes was a critical review of the experiences in coping with the “swine flu” pandemic, with the result that since 2013, less formal criteria and more “risk-based approaches” have been the fundamentals of Phases are defined by the World Health Organization. As a result, the local influenza pandemic plans were also adjusted.

According to the German doctor Wolfgang Wodarg , the WHO's pandemic plan was drawn up by industry-sponsored experts in 1999, which was then prescribed as the International Health Regulations (IHR 2) in 2007. Wodarg initiated an investigation by the Council of Europe. Its Committee on Social Affairs, Health and Family criticized the lack of transparency in dealing with the pandemic and that the WHO and other public health institutions had gambled away some of the trust of the European public.

See also

literature

- Alexander S. Kekulé : What we can learn from swine flu . In: From Politics and Contemporary History . (APuZ) 52/2009, pp. 41-46.

Web links

- World Health Organization (WHO): Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 .

- European Commission, Directorate-General "Health and Consumer Protection": Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: we need to ensure that Europe is prepared.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - USA: 2009 H1N1 Flu (English and Spanish)

- Google Maps: Position map of the number of cases related to "swine flu"

Individual evidence

- ↑ Outbreak of Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection --- Mexico, March - April 2009.

- ↑ Weekly Virological Update on August 5 , 2010. World Health Organization (WHO), August 5, 2010, accessed April 15, 2020 .

- ↑ Robert Roos: CDC estimate of global H1N1 pandemic deaths: 284,000. Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, June 27, 2012, accessed April 15, 2020 .

- ^ Karl Johansen et al .: Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccines in the European Union . In: European Center for Disease Prevention and Control [ECDC] (Ed.): Eurosurveillance . tape 14 , no. 41 , October 15, 2009 ( full text [PDF]).

- ↑ WHO: Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 84 from January 22, 2010.

- ↑ a b Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Two Children - Southern California, March – April 2009. In: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report . Volume 58, No. 15, April 24, 2009, pp. 400-402.

- ↑ H1N1 in post-pandemic period. WHO, August 10, 2010.

- ↑ WHO: Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 112 from August 6, 2010.

- ↑ a b First Global Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Mortality Released by CDC-Led Collaboration ( en-us ) June 25, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ a b Dawood FS, Iuliano AD, Reed C, Meltzer MI, Shay DK, Cheng PY, Bandaranayake D, Breiman RF, Brooks WA, Buchy P, Feikin DR, Fowler KB, Gordon A, Hien NT, Horby P, Huang QS , Katz MA, Krishnan A, Lal R, Montgomery JM, Mølbak K, Pebody R, Presanis AM, Razuri H, Steens A, Tinoco YO, Wallinga J, Yu H, Vong S, Bresee J, Widdowson MA: Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modeling study . In: The Lancet Infectious Diseases . 12, No. 9, September 2012, pp. 687-95. doi : 10.1016 / S1473-3099 (12) 70121-4 . PMID 22738893 .

- ↑ Free citizen hotline for new flu (swine flu) from May 1, 2009. ( Memento from February 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Press release of the German Federal Ministry of Health from April 30, 2009. Quote: “From Friday, May 1 At 10 a.m., the Federal Ministry of Health offers a free number that citizens can use to find out more about “swine flu”. [...] "

- ↑ S. Beermann: Between hysteria and vaccination chaos - conversation with Thorsten Wolff, RKI Berlin . In: Laborjournal . 3, 2010, pp. 40-43.

- ↑ a b c “North American flu” is not an animal disease. No risk of infection when coming into contact with pigs . ( Memento of December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Press release No. 078 of the German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection of April 30, 2009. Quote: “The term 'swine flu' is misleading. The World Organization for Animal Health has therefore named the disease that occurs in humans 'North American flu': The events of the 'North American flu' cannot be compared with the avian influenza popularly known as 'bird flu'. Avian influenza caused by the H5N1 pathogen is an animal disease. The 'North American flu', on the other hand, is a human infection that - without contact with pigs - can be passed on from person to person, for example by sneezing, coughing, or shaking hands. [...] "

- ↑ Bernd Liess (Ed.): Virus infections in domestic and farm animals. 2nd Edition. Schlütersche, Hannover 2003, ISBN 3-87706-745-X , p. 88.

- ↑ The strange dispute over the name of the epidemic. On: spiegel.de of April 29, 2009.

- ↑ a b Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. ( Memento of October 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Website of the European health authority ECDC with information on the H1N1 pandemic.

- ^ Standardization of terminology of the pandemic A (H1N1) 2009 virus. In: WHO (Ed.): Weekly Epidemiological Record (WER). Volume 86, No. 43, 2011, p. 480. Quotation: “In order to minimize confusion and to differentiate the virus from the former seasonal A (H1N1) viruses circulating in humans before the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 pandemic, the advisers to the WHO technical consultation on the composition of influenza vaccines for the southern hemisphere 2012 season, after discussion on 26 September 2011, advise WHO to use the nomenclature below: A (H1N1) pdm09 . "

- ↑ Michael Coston: WHO: Call It A (H1N1) pdm09. In: Avian Flu Diary. Michael P. Coston, October 21, 2011; Retrieved February 29, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Rebecca J. Garten et al .: Antigenic and Genetic Characteristics of Swine-Origin 2009 A (H1N1) Influenza Viruses Circulating in Humans. In: Science . Volume 325, No. 5937, 2009, pp. 197-201, doi: 10.1126 / science.1176225 .

- ↑ a b Serum Cross-Reactive Antibody Response to a Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus after Vaccination with Seasonal Influenza Vaccine. In: Morbidity and Mortality Report Weekly. Volume 58, No. 19, May 22, 2009, pp. 521-524.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: CDC Briefing on Public Health Investigation of Human Cases of Swine Influenza, April 23, 2009.

- ↑ Ignacio Mena et al .: Origins of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in swine in Mexico. In: eLife. Online publication, e16777, June 28, 2016, doi: 10.7554 / eLife.16777 .

- ↑ Update: Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infections Worldwide . In: Morbidity and Mortality Report Weekly. Volume 58, No. 17, May 6, 2009, pp. 453–458 6. Accessed February 29, 2020.

- ↑ a b c Christophe Fraser et al .: Pandemic Potential of a Strain of Influenza A (H1N1): Early Findings. In: Science. Volume 324, No. 5934, pp. 1557-1561, doi: 10.1126 / science.1176062 .

- ↑ Michael Cooking, President of the German Society for General Practice in an interview with the ARD magazine monitor . monitor - Horror scenarios: The swine flu and the media ( Memento from December 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Broadcast from November 19, 2009 (video on Youtube)

- ↑ Peter Collignon, Director “School of Medicine”, University of Canberra (Australia) in an interview with the ARD magazine monitor . monitor - Horror scenarios: Swine flu and the media ( Memento from December 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), broadcast from November 19, 2009, (video on Youtube)

- ↑ James F. Bishop et al .: Australia's Winter with the 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Virus . In: The New England Journal of Medicin. Volume 361, December 31, 2009, pp. 2591-2594, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMp0910445 .

- ^ WHO global influenza preparedness plan. (PDF; 373 kB), Geneva 2005. Short version as a leaflet (PDF). ( Memento from May 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b World now at the start of 2009 influenza pandemic. On: who.int of June 11, 2009.

- ↑ Swine influenza: Statement by WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan. On: who.int of April 25, 2009.

- ↑ Swine influenza: Statement by WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan. On: who.int of April 27, 2009.

- ^ Influenza A (H1N1): Statement by WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan. On: who.int of April 29, 2009.

- ↑ Second highest warning level proclaimed. WHO expects swine flu pandemic. ( Memento from May 2, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Tagesschau from April 29, 2009

- ↑ a b RKI Influenza Guide. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 29, 2009 ; Retrieved November 14, 2009 .

- ↑ WHO Checklist for Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Planning. Geneva, 2005. (PDF; 152 kB)

- ^ Current WHO phase of pandemic alert. ( Memento from June 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ True extent of the outbreak is claimed to be 300 times worse than government agency admits. On: independent.co.uk of May 24, 2009.

- ↑ Transcript of virtual press conference of the WHO from May 18, 2009 (PDF; 64 kB).

- ↑ Leaflet Influenza A (H1N1) - New flu home quarantine. ( Memento from November 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Federal Ministry of Health (Austria) from August 7, 2009.

- ↑ a b Transcript of virtual press conference, WHO 13 July 2009. (PDF, 53 kB)

- ↑ K. Johansen, A. Nicoll, B. C. Ciancio, P. Kramarz: Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccines in the European Union. In: Eurosurveillance. Volume 14, No. 41, 2009.

- ↑ Germany orders 50 million vaccine doses against swine flu . On: mirror de of July 24, 2009.

- ↑ Robert Koch Institute (Ed.): Epidemiological Bulletin No. 41/2009 . October 12, 2009 ( rki.de [PDF; accessed March 2, 2020]). , Pp. 404-405.

- ↑ New Influenza: Standing Vaccination Commission presents vaccination recommendations. (PDF; 59 kB) In: Press release. Robert Koch Institute, November 8, 2009, accessed on March 2, 2020 : “The Standing Vaccination Commission (STIKO) has now published its recommendations for vaccination against the new influenza. She recommends this vaccination initially for medical staff, the chronically ill and pregnant women. The World Health Organization has also recommended vaccinating these groups as a matter of priority. The STIKO expressly points out that this recommendation cannot be static in the event of a dynamic infection process and a constantly changing and expanding data situation, but is continuously checked and adjusted if necessary. The STIKO points out that in principle all population groups can benefit from the vaccination against the new influenza A (H1N1). "

- ^ Swine flu: Vaccination starts on October 26th. On: welt.de from October 8, 2009.

- ↑ Swine flu: vaccination campaign begins slowly. On: stern.de from October 26, 2009.

- ↑ Combating epidemics: Such is the situation on the swine flu front. On: spiegel.de from November 13, 2009.

- ^ Bettina Freitag: Special treatment for civil servants and ministers? ( Memento of October 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: tagesschau.de of October 18, 2009.

- ↑ Jens Berger: In the pig gallop into vaccination chaos . In: Telepolis of October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Swine flu vaccinations: everything under control? (II) ( Memento of November 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 24 kB) Published in: blitz arznei-telegram of September 25, 2009.

- ↑ Swine flu: Celtura vaccine approved. ( Memento of December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Published in: pharmische-zeitung.de of November 5, 2009.

- ↑ No buyers for the swine flu vaccine ( Memento from May 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: tagesschau.de from May 10, 2010.

- ↑ Swine Flu: Countries Destroy Millions of Doses of H1N1 Vaccine. In: spiegel.de. November 25, 2011, accessed March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Austrian Influenza Pandemic Plan. ( Memento from October 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Status: June 12, 2009.

- ↑ Swine flu: No dispute in Austria about vaccination ( Memento from October 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: aerztezeitung.de from October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Large rush for swine flu vaccination ( Memento from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: steiermark.orf.at from November 9, 2009.

- ↑ a b Evaluation of the H1N1 vaccination strategy in Switzerland. ( Memento from January 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Federal Office of Public Health (Switzerland), April 2010.

- ↑ a b Swissmedic grants approval for pandemic vaccines ( Memento of December 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: swissmedic.ch of October 30, 2009. Quotation: “Swissmedic therefore has the use of Pandemrix for pregnant women and children under 18 years of age and adults over 60 years of age not yet admitted. However, adults over 60 can be vaccinated with Pandemrix based on the recommendations of the FOPH. Accordingly, Focetria is recommended for use in adults and children from six months. During pregnancy and breastfeeding, the attending physician must weigh up the possible advantages and disadvantages of a vaccination according to the current vaccination recommendation of the Federal Office of Public Health. "

- ↑ Swissmedic expands approval for Pandemrix ( Memento of December 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: swissmedic.ch of October 30, 2009. Quote: "The swine flu vaccine is now also approved for people over 60 years of age."

- ↑ Swissmedic grants approval for Celtura ( Memento of December 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: swissmedic.ch of November 13, 2009. Quote: “On the basis of the available clinical data, Celtura was developed for children from three years of age and for adults of all Age groups allowed. "

- ↑ Vaccination against pandemic flu Influenza A H1N1 (2009) ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: bs.ch of November 23, 2009.

- ↑ 7561 people vaccinated in the Baselland vaccination centers ( memento of December 2, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: baselland.ch of November 29, 2009.

- ↑ a b sda-ats: Switzerland disposes of vaccines worth 56 million francs. (PDF) swissinfo, April 26, 2011, accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Switzerland sold H1N1 vaccine to Iran ( memento from March 2, 2020 in the Internet Archive ) Federal Office of Public Health (Switzerland) from January 28, 2010.

- ↑ Influenza Weekly Report. Calendar week 46 (November 7th to November 13th, 2009). On: influenza.rki.de , last viewed on March 2, 2020.

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Justice (Germany): Ordinance on compulsory reporting of influenza caused by the new virus ("swine flu") that first appeared in North America in April 2009. Issued on April 30, 2009. Published in: Bundesanzeiger . Special edition No. 1, May 2, 2009, p. 1589, full text (PDF).

- ↑ Doctors no longer have to report suspected swine flu cases ( Memento from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: aerzteblatt.de from November 13, 2009.

- ↑ ICD-10-GM 2009: Code J09 for the new flu ("swine flu" or "Mexico flu"). On: idw.de of April 30, 2009.

- ↑ ICD-10-GM-2020. On: icd-code.de , last viewed on March 2, 2020.

- ↑ FAQ on influenza A / H1N1 (swine flu). ( Memento from September 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Hessian Ministry of Labor, Family and Health, as of October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Influenza Virus Database.

- ↑ WHO information for laboratory diagnosis of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus inhumans - revised. (PDF, 744 kB) On: who.int of November 23, 2009.

- ↑ FluView - Weekly US Influenza Surveillance Report. Influenza surveillance results in the United States updated weekly.

- ↑ Nila J. Dharan et al .: Infections With Oseltamivir-Resistant Influenza A (H1N1) Virus in the United States. In: JAMA. Volume 301, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1034-1041, March 2, 2009, doi: 10.1001 / jama.2009.294 .

- ↑ Weekly epidemiological record, No. 24/2009. (PDF, 519 kB) On: who.int of June 12, 2009.

- ^ ECDC Situation Report. Influenza A (H1N1) infection. ( Memento from February 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) PDF, 295 kB. Published on ecdc.europa.eu on June 12, 2009.

- ^ Information for Healthcare Professionals. Mandatory Adverse Event Reporting for Emergency Use of Peramivir IV Under EUA. ( Memento of January 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Peramivir information for doctors in the USA, on: fda.gov of October 23, 2009.

- ↑ Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 72. On: who.int from October 25, 2009

- ↑ Transcript of virtual press conference of the WHO of 7 July 2009 (PDF; 70 kB).

- ↑ Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 86. On: who.int from February 5, 2010.

- ^ Preparing for the second wave: Lessons from current outbreaks. On: who.int of August 28, 2009.

- ^ Secretaría de Salud, Mexico: Siruatión actual y retos para enfrentar las adicciones en al ámbito laboral. ( Memento of June 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on April 23, 2009 (Spanish).

- ↑ Mexico fears greater number of victims from swine flu. ( Memento from May 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on dradio.de on April 26, 2009.

- ↑ Swine flu: WHO sees potential for pandemic. On: diepresse.com (Austria) from April 25, 2009.

- ^ Secretaría de Salud, Mexico: Suspensión de clases en el Distrito Federal y el Estado de México por influenza. ( Memento of April 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on April 24, 2009.

- ↑ Human infection with new influenza A (H1N1) virus: clinical observations from Mexico and other affected countries, May 2009. (PDF; 1.5 MB) In: WHO (Ed.): Weekly Epidemiological Record. Volume 84, No. 21, 2009, pp. 185-196.

- ↑ Secretaría de Salud México, Influenza A (H1N1) ( Memento of February 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Published on May 29, 2009.

- ↑ Experts probe deadly Mexico flu. On: bbc.co.uk of April 24, 2009.

- ↑ Pandemic 'Imminent': WHO Raises Swine Flu Pandemic Alert Level to 5. On: abcnews.go.com of April 29, 2009.

- ^ Schwarzenegger, Obama boost efforts against swine flu. ( Memento of April 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Published on: latimes.com of April 29, 2009.

- ^ Governor issues proclamation to confront swine flu outbreak. ( Memento of October 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Published on missionviejolife.org on April 28, 2009.

- ↑ Press Briefing Transcripts: CDC Telebriefing on Investigation of Human Cases of Novel Influenza A (H1N1), June 26, 2009.

- ↑ CDC Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Influenza Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths in the United States. On: cdc.gov of May 14, 2010.

- ↑ WHO: Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. World Health Organization website with information on the H1N1 pandemic.

- ↑ Influenza A / H1N1. ( Memento of June 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) World Health Organization website with information on the H1N1 pandemic in Europe.

- ^ Report on the epidemiology of influenza in Germany, season 2009/10. On: rki.de , as of May 2010.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin 50/09. (PDF) On: rki.de of December 14, 2009, p. 520: Vaccination after reaching the apex of the current wave of New Influenza A (H1N1).

- ↑ Influenza weekly report , calendar week 8 (February 20 to February 26, 2010). (PDF; 380 kB) On: rki.de , accessed on March 2, 2020.

- ↑ Matthias Bartsch, Annette Bruhns, Jürgen Dahlkamp, Michael Fröhlingsdorf, Hubert Gude, Dietmar Hipp, Julia Jüttner, Veit Medick, Lydia Rosenfelder, Jonas Schaible, Cornelia Schmergal, Ansgar Siemens, Lukas Stern, Steffen Winter: Geisterhand . In: Der Spiegel . No. 12 , 2020, p. 28-32 ( Online - Mar. 14, 2020 ).

- ↑ Swine flu all-clear. On: oe1.orf.at from April 8, 2017.

- ^ One Year New Flu - The Ministry of Health Measures. Federal Ministry of Health (Austria). On: ots.at of April 22, 2010.

- ↑ a b To Alberta Swine Herd Investigated for H1N1 Flu Virus. ( Memento from September 27, 2011 on the Internet Archive ) Canadian Food Inspection Agency, May 2, 2009.

- ↑ Robert B. Belshe: Implications of the Emergence of a Novel H1 Influenza Virus. In: The New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 360, No. 25, 2009, pp. 2667-2668, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMe0903995 .

- ↑ Dinah Henritzi, Philipp Peter Petric, Nicola Sarah Lewis et al .: Surveillance of European Domestic Pig Populations Identifies an Emerging Reservoir of Potentially Zoonotic Swine Influenza A Viruses. In: Cell Host & Microbe. Online advance publication of July 27, 2020, doi: 0.1016 / j.chom.2020.07.006 .

- ↑ H1N1 experiment: pigs can also get swine flu. On: spiegel.de of July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Elke Lange et al: Pathogenesis and transmission of the novel swine-origin influenza virus A / H1N1 after experimental infection of pigs . In: Journal of General Virology . tape 90 , no. 9 , September 1, 2009, p. 2119-2123 , doi : 10.1099 / vir.0.014480-0 .

- ↑ Chile: Swine flu virus first discovered in turkeys. On: spiegel.de from August 21, 2009.

- ↑ Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 84. On: who.int from January 22, 2010.

- ↑ All-clear: WHO declares the end of the swine flu pandemic. On: welt.de from August 10, 2010.

- ↑ Swine flu is seasonal influenza this year. On: derstandard.at of January 4, 2011.

- ↑ Chronicle of a hysteria. On: spiegel.de of March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Report on the epidemiology of influenza in Germany, season 2014/15. On: rki.de , Berlin 2015, p. 44.

- ↑ RKI: Has the World Health Organization changed the definition of a pandemic phase so that a pandemic could be declared? On: rki.de from August 2, 2010.

- ^ Current WHO phase of pandemic alert. ( Memento from June 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

-

↑ WHO (Ed.): Pandemic Influenza Risk Management , p. 10. World Health Organization, Geneva 2017.

WHO: Why has the guidance been revised? Explanations on the revision of the pandemic guidelines from 2013, last viewed on February 28, 2020. - ↑ As an example: Municipal Influenza Pandemic Plan of the City of Frankfurt am Main, Update 2012, p. 11. (Last viewed on March 3, 2020) and background information from the State Medical Association of Hesse ( Memento of December 11, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 475 kB) In: Hessisches Ärzteblatt 12/2007.

- ↑ Original quote: "" Influenza Pandemic Plan: The Role of WHO and Guidelines for National and Regional Planning "was drafted by industry-sponsored experts together with the European Scientific Working Group on Influenza (ESWI). The ESWI is an organization that is financed by pharmaceutical companies 21 who have a great economic interest in this topic. "; in Wolfgang Wodarg: "False alarm: The swine flu pandemic" in BIG PHARMA, Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen Ed., Piper 2015, p. 310 ff; Subchapter The WHO can be bought ff; (pdf file) , last accessed in March 2020.

- ↑ Albrecht Meier: Hearing: Council of Europe criticizes panic-mongering in the case of swine flu. Experts have accused the World Health Organization of unnecessarily contributing to the American flu excitement. Billions in costs were the result ; at zeit.de, last accessed in March 2020.

- ^ Council of Europe , Social, Health and Family Affairs Committee: The handling of the H1N1 pandemic: more transparency needed . AS / Soc (2010) 12, March 23, 2010.

- ↑ The Sponsored Pandemic - WHO and Swine Flu . In: Arznei-Telegramm , 41, 2010, pp. 59–60.