Avian flu H5N1

Avian influenza H5N1 is a viral disease in birds caused by the influenza A virus H5N1 . Like all other poultry diseases caused by influenza viruses, avian flu H5N1 is a notifiable animal disease in captive birds and wild birds in many countries , against which official measures can be taken immediately to control it and prevent its spread. In individual cases the viruses have been transmitted to mammals and humans , the disease is consequently a zoonosis .

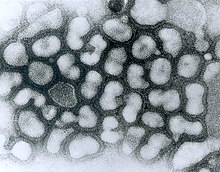

H5N1 virus

Influenza A / H5N1 virus is an enveloped single (-) - stranded RNA virus from the Orthomyxoviridae family . The diameter of the virus is about 100 nanometers, it has about 14,000 nucleotides .

The ability of the pathogen to become infected is not very high in the outside world and can be rendered harmless for the spectrum of activity "limited virucidal" by using disinfectants with declared effectiveness. However, the virus - protected by organic material such as body secretions, feces and the like - can survive for several weeks in animal stalls and especially at low temperatures. The viruses remain infectious at 4 ° C, for example for about 30 to 35 days in faeces, poultry meat or stored eggs, but only for six days at 37 ° C. According to previous knowledge, the viruses are no longer infectious if they have been exposed to temperatures above 70 ° C, so that transmission via cooked eggs or other cooked poultry and meat products is excluded.

Animal-to-animal transmission routes

According to the New Scientist , the consequences of the H5N1 outbreaks, which have occurred frequently since 1997, are the worst wave of diseases that has ever become known among animals, comparable at best to rinderpest . In principle, the same infection pathways are observed in breeding poultry as in other influenza viruses : The H5N1 viruses can be spread through fecal particles , which can also find their way into industrial poultry feed via so-called "chicken waste" (animal remains); they can also be spread through blood, clothing and tools during slaughter.

However, at a joint conference of the FAO and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) at the end of May 2006, researchers from Erasmus University (Rotterdam) pointed out that, unlike all other known influenza viruses, H5N1 viruses in wild birds apparently more strongly via the respiratory tract than are excreted in the faeces. This may explain why not a single case of H5N1 was found among nearly 100,000 live wild bird faecal samples analyzed in Europe in the 10 months leading up to May 2006.

It is controversial what proportion of the trade in birds and poultry products is attributable to the spread of A / H5N1 and what proportion goes to wild birds. The US health authority CDC explains in this context that individual wild birds around the world carry the virus without contracting it; H5N1 detection was first known from America in 2015, in Australia A / H5N1 does not seem to have arrived yet.

In 2010 a study confirmed that pintail ducks equipped with micro-transmitters stayed in waters that were home to infected whooper swans on their flight routes between Japan and the north Asian mainland in 2008 . This was interpreted in support of the hypothesis that wild birds can spread the virus along their migration routes. At the regional level, it was calculated for China in 2020 that the spread of avian influenza viruses will also take place along the trade routes for poultry.

Birds

The symptoms of the acute course of A / H5N1 infection are identical to the symptoms caused by other subtypes of avian influenza virus. The course of the disease is particularly severe in domestic poultry, especially in chickens and turkeys. As incubation period are from the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) "a maximum of 21 days," reported.

In addition to signs of general weakness ( apathy , inappetence , dull, shaggy plumage), there are high fever , difficult breathing with open beak, edema (i.e. swelling due to fluid build-up) on the head, neck, crest, wattles, legs and feet, blue discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes , watery, slimy and greenish diarrhea , neurological disorders (strange posture of the head, motor disorders ). The laying performance decreases, the eggs are thin-walled or shell-less. The mortality in infected domestic poultry flocks is very high: Death occurs in nearly all animals.

Wild water birds

A / H5N1 was first noticed in Asia because this virus also killed many migratory birds that were less endangered by other influenza A viruses. Influenza A viruses are widespread among wild ducks and other waterfowl ; these animals are therefore referred to as the “natural reservoir for the virus”. It is often characteristic of such reservoir hosts that they do not become ill themselves, or at least do not become seriously ill. Evolutionary biologists interpret such forms of coexistence to the effect that, in the long term, it is primarily those virus variants that do not kill their hosts that will spread in the population of their reservoir hosts. If the host is killed - especially very quickly - the virus population resident in the host also dies with it; Variants of a virus type that use it to multiply and spread over the long term ( attenuated viruses) therefore have a greater chance of reproduction .

Migratory water birds, sea birds and shorebirds are considered to be less susceptible to the disease. But they too can be vectors , and their migratory behavior ( bird migration ) can contribute to the spread.

In southern China and Hong Kong , more than 13,000 faeces and other samples from wild birds have been tested for A / H5N1 since the beginning of 2003 without any virus being found. It was not until the beginning of 2005 that H5N1 viruses were detected in six apparently healthy wild ducks on Lake Poyang in the Chinese province of Jiangxi . The Chinese researchers also examined more than a thousand serological samples from wild ducks and found antibodies to A / H5N1 in three percent of them, which was considered to be indicative of previous infection. The researchers suspected that individual migratory birds can spread the virus over long distances, but that frequent local outbreaks can be traced back to infected poultry.

Similar results became known from Europe in 2007: Researchers from Sweden and the Netherlands had examined 37,000 free-living waterfowl in Northern Europe over eight years and found influenza viruses in six percent of the animals, but not a single H5N1 infection.

The first major mass extinctions among wild birds was an H5N1 outbreak at North China Qinghai -See (a resting place for migratory birds), where in 2005 a number of bar-headed geese died.

Domestic fowl

An infection with A / H5N1 or other influenza A viruses can lead to serious illnesses and even rapid death, especially in chickens and turkeys , but also in pheasants , quails and guinea fowl . Pigeons are not said to be very susceptible to A / H5N1 themselves, but it is feared that they spread the pathogen as mechanical vectors in the plumage. Because of the possible, considerable economic damage, provisions for protective measures after the occurrence of influenza infections have been taken on the basis of national animal disease laws through various ordinances - in Germany for example the avian influenza ordinance .

It is not yet known from which host animals A / H5N1 was first transferred to breeding poultry. It is believed, however, that the viruses were spreading among southern Chinese ducks and geese even before they first emerged among chickens (in 1997 in Hong Kong). Due to the rapid reaction of the Hong Kong authorities, who had the entire breeding poultry population killed in 1997, apparently all virus variants dangerous for chickens were eradicated at the time.

When the pathogen outbreaks again at the end of 2003 / beginning of 2004 in other regions of Southeast Asia, no similar draconian measures were taken, so that A / H5N1 was able to spread from year to year. A procedure like the one in Hong Kong would hardly have been feasible in view of the economic importance of poultry farming in other regions of Southeast Asia today. Thailand , Indonesia and Vietnam increased their poultry production eightfold between 1975 and 2005, while Chinese production tripled in the 1990s. Most of the chicken today comes from fattening factories that are close to large cities and belong to large companies; for viruses that can factory farming produce good growth conditions. According to the bird protection organization BirdLife , there are also numerous poultry farms around Lake Qinghai , where mass deaths of wild birds by A / H5N1 were detected for the first time in 2005 . With the support of the FAO, a fish farm was also built there, with the chicken droppings from the poultry farms being used as fish feed.

In the summer of 2005, Robert G. Webster from the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis (USA) and his research colleagues from Asia found that the subtype A / H5N1 is now making domestic ducks in Asia less sick than it was years ago. This means that there is a risk that these domestic ducks, as new reservoir hosts, will become a reservoir for A / H5N1 variants and that they will also be able to increasingly transmit the pathogens to other animal species and humans, because they excrete the virus for an unusually long time via the faeces and respiratory tract. In fact, individual cases of H5N1 infection in humans were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) from China from 2006 onwards , in which the infection was apparently caused by poultry that appeared to be "healthy" and that came from an area where none Wild or farmed animals died of A / H5N1.

Mammals

Mammals are less susceptible to the virus, but have also been infected occasionally in recent years. In May 2005, for example, the journal Nature reported that official bodies in Indonesia had detected A / H5N1 in pigs . Smears from the nose of 702 Indonesian pigs with no health problems that were analyzed between 2005 and 2007 provided evidence that 52 animals (7.4%) were infected with the H5N1 virus. Previously, there had already been reports from China of H5N1 finds in pigs.

The Dutch researcher Albert Osterhaus was in the time quoted on 19 January 2006 that A / H5N1 dogs, horses, pumas, tigers and leopards have infected in animal experiments and mice, ferrets , monkeys and cats. In March 2006, an infected stone marten was discovered on the island of Rügen .

fishes

According to the FLI , according to the current state of science, there is no need to worry that fish can become infected with A / H5N1 viruses and transmit it to humans. To date, there are no known viruses in birds and mammals that would be infectious for fish. Conversely, no viral disease in fish that can be transmitted to humans or birds has so far been detected.

Worldwide spread from 2004

As early as 1959 and 1991, there were two local outbreaks of a previously known, less pathogenic form of A / H5N1 in poultry holdings in Great Britain. First in 1997 and then between December 2003 and summer 2004, starting in the region around Hong Kong , there were repeated larger outbreaks of a highly pathogenic variant of A / H5N1 among breeding poultry in several countries in Southeast and East Asia , which probably only emerged in 1996. The People's Republic of China , South Korea , Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia , Malaysia and Japan were initially affected . Several larger outbreaks among wild birds were also observed in 2005.

Transports between poultry farms in particular, but also bird migrations , are held responsible for the fact that the epidemic was able to spread more and more widely from 2005 onwards.

In summer 2005, A / H5N1 was detected outside of Southeast Asia, initially in poultry flocks in Siberia ( Novosibirsk region ) and Kazakhstan , and also in Mongolia and later in the Urals . As of October 2005, there were confirmed H5N1 infections among poultry in Romania , Croatia and Turkey . In November 2005, A / H5N1 was also detected (in a single animal) in Kuwait , and there have been repeated outbreaks in Ukraine since then .

In the opinion of the chairman of the influenza program of the World Health Organization, Klaus Stöhr , the spread of the pathogen A / H5N1 could not be stopped as early as the beginning of 2006 . "We believed that when the virus was not yet spread among wild birds," said Stöhr on February 14, 2006 in the hr . Because of the transmission by wild birds, many measures to contain the spread of the pathogen - such as baggage checks and the ban on animal transport - have become ineffective.

In its February 18, 2006 issue, the New Scientist magazine pointed out that all outbreaks in Europe and Africa “have so far been close to the wintering sites for ducks that spend the summer in Siberia”. On May 13, 2006, New Scientist used the example of the pintail to show that due to overlapping settlement areas of subpopulations, the east-west spread of A / H5N1 and, due to north-south migrations, the spread from Siberia to the Middle East and Africa can be explained.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) announced the other in November 2005 that even after extensive testing in the affected countries under the clinically normal migratory birds no A / H5N1 viruses were detected. All wild birds that tested positive worldwide were found dead and mostly in the vicinity of poultry farms. Even among 11,000 wild birds screened in 2006 and 2007 in 19 countries in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa, not a single H5N1 infected individual was found.

A group of US ornithologists reported in the journal Science in 2006 that Japan had remained A / H5N1-free since 2004 after the country introduced strict controls on poultry imports. Japan is located in the area of bird migration from southern China and other areas with repeated H5N1 outbreaks. These ornithologists also concluded that the causes of the H5N1 spread could very well be poultry transports, contaminated transport containers and infectious waste. It was not until 2007 that a brief H5N1 outbreak occurred again in Japan.

Since the first appearance described below, there have been occasional, sometimes even frequent, outbreaks on all continents.

South East Asia

Since 2006, numerous countries in Southeast Asia have repeatedly reported H5N1 infections to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). The virus was particularly widespread initially in China and Hong Kong , then in Thailand , Vietnam , Malaysia and Cambodia ; it later spread to South Korea , India , Pakistan , Bangladesh , Myanmar (Burma), Afghanistan and Laos . In Japan there were minor A / H5N1 outbreaks in early 2004, January 2007 and April 2008. In January 2009, the virus was detected in Nepal for the first time, and in April 2013, 164,000 ducks were killed in North Korea after H5N1 infections. A similar number of dead and preventively slaughtered poultry was also reported from Nepal in 2013.

Siberia, Europe, Middle East

After the major H5N1 outbreaks in 2005, only a few H5N1 infections have been known from Siberia and the successor states of the Soviet Union since 2006. However, a larger chain of infection occurred in February 2007, for which the “Sadovod Market” in Moscow proved to be the starting point.

However, from the beginning of 2006, H5N1 outbreaks occurred for the first time in Turkey and Northern Cyprus , Iraq , Iran , Israel , Jordan and the Palestinian Territories . In Eastern Europe a particularly high number of outbreaks were reported from Romania , which - also in the country itself - was attributed to inadequate crisis management. Also affected by H5N1 infections from 2006 were Poland , Hungary , Slovakia , Slovenia , Bulgaria , Albania and Serbia .

Presumably originating in Eastern Europe and Western Turkey, the H5N1 infection then spread in early 2006 on the one hand towards southern Europe to Greece and to Sicily , on the other hand along the Baltic Sea to northern Germany and Denmark . Austria, southern Germany and Switzerland were in the area of a third wave. In the following years, isolated H5N1 infestations were also registered in Europe, for example in January 2007 in Hungarian and south-east English poultry flocks, in summer 2007 in Lorraine as well as in several German federal states in wild birds found dead and in November 2007 again in England on the border between Norfolk and Suffolk. In the spring of 2008, for example, infected wild birds were discovered near Lucerne , in October 2008 the infestation of a poultry population in Saxony and in early March 2009 39 infected wild ducks at Lake Starnberg .

Africa, Arabian Peninsula

At the beginning of January 2006 there was an outbreak of A / H5N1 in a large battery of laying hens for the first time in Africa, in the Nigerian city of Jaji in the state of Kaduna . By the end of June 2006, H5N1 infections had been reported from 14 of Nigeria's 31 states. Further outbreaks were then reported from Niger , Egypt , Cameroon , Sudan , Burkina Faso , Djibouti , Ivory Coast , Ghana and Togo .

On February 13, 2007, several sick falcons were discovered in the Kuwait Zoo and were later found to be infected with H5N1. At the same time, several dozen A / H5N1 chickens were found elsewhere in Kuwait that had been sold in local markets. On March 12, 2007, a local poultry outbreak was detected in Saudi Arabia (administrative unit ash-sharqiyah ) according to a report from the Ministry of Agriculture to the OIE, which was attributed to "contact with wild birds". At the end of 2007, the first H5N1 detection from Benin became known. In October 2009, nine vultures fell on a school playground in Cocody (Ivory Coast) and died there as a result of the H5N1 infection.

North America

A highly pathogenic variant of A / H5N1 was first detected in North America in January 2015 , in Whatcom County , Washington , in a shot wild bird, a North American teal ( Anas carolinensis ); According to the analyzes, this variant is a previously unknown reassortment . Some genes of this H5N1 variant are largely identical to a virus found in December 2014 in the same Washington county. There the subtype A / H5N8 had been discovered in a privately held gyrfalcon ; According to the analyzes, other genes have migrated from subtype A / H5N2 to A / H5N1 by means of reassortment. This interpretation was confirmed by virus detection from a wigeon . Shortly afterwards, A / H5N1 was also detected in Canada , in a private chicken herd in British Columbia .

Combat

At the end of May 2006, the UN Organization for Agriculture and Food ( FAO ) issued guidelines aimed at reducing the risk of infection with A / H5N1. The recommendations deal with the risk of infection from animal to animal as well as from animal to person, advice on keeping poultry and tips on improving hygiene when handling dead animals are given: These animals would have to be burned or buried deep (see Sect. also web links , FAO guideline). In the individual countries concerned, similar, but in some cases very different, measures were often prescribed.

In the EU, A / H5N1 is controlled on the basis of EU law and, in all European countries, on the basis of national laws. In Germany, this is primarily the Animal Disease Act and the Avian Influenza Ordinance derived from it .

Preventive Kills and Trade Restrictions

These regulations currently stipulate that in the event of outbreaks of influenza diseases in animal husbandry, the entire animal population of the affected keeper must be killed. The carcasses are burned or otherwise rendered harmless to prevent transmission to other livestock. Therefore, the number of animals killed is usually much larger than the number of animals that have been proven to be infected. This in turn means that there are no reliable data on the number of sick animals and even rough estimates of the number of animals killed as a preventive measure. In addition, protection zones are set up around the place where infected animals were found, in which the transport of birds and poultry products is partly prohibited and partly subject to approval. These protective measures, originally intended for influenza diseases in animal husbandry, are now also applied to individual finds of infected wild birds.

On the basis of this legal situation in Germany u. a. since October 30, 2005 poultry markets and bird fairs only allowed in exceptional cases; in some German federal states and in Austria they are even completely banned. During a hunt, decoys may no longer be used and poultry stocks may only be soaked with tap water. The extraction of drinking water from the wild (rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, etc.) is currently prohibited.

Furthermore, since mid-February 2006 in Germany and Austria, as well as in numerous other countries, there has been a ban on free-range keeping of poultry (“ compulsory stable ”), for which various exceptions have been in effect in Germany since mid-May 2006. Numerous developing and emerging countries have banned or restricted so-called backyard keeping, which is sharply criticized by those affected and by opponents of the poultry companies, but welcomed by the agricultural industry.

The European Union and Switzerland have also imposed an import ban on all poultry as well as wild birds, poultry meat, eggs and untreated feathers from countries affected by H5N1 outbreaks. In most countries, however, imports and internal trade in hatching eggs and chickens are not or not effectively controlled. One example is Turkey, where, according to the FAO, A / H5N1 was spread by factory farms selling low-quality poultry in large quantities to indigent smallholders.

The monitoring of international trade in industrial poultry feed , which also contains chicken meat and chicken waste and thus remains of excrement, feathers or litter , is still in its infancy .

Wild bird monitoring

In order to protect domestic poultry from the possible transmission of influenza viruses by wild birds, an expanded monitoring program ( wild bird monitoring ) has been carried out in Europe since 2005 , primarily for wild ducks and geese. The sampling program is based, among other things, on sentinel systems ("guard animal systems"), in which flightless mallards are kept and wild birds that live in the wild are attracted by regular feeding, on ringing stations, nature conservation authorities and hunters. Samples such as throat and cloacal swabs, blood or feces are sent to the responsible examination facility, where they are tested for influenza viruses.

After examining almost 37,000 wild ducks, geese and other waterfowl for influenza viruses in Sweden and the Netherlands over a period of eight years, a group of experts reported in spring 2007 that an average of six percent of the animals had influenza viruses, but no A / H5N1 -Viruses. The infection rates were subject to considerable seasonal fluctuations: While influenza viruses were rarely found in spring, over 20 percent of the ducks were found to be infected with influenza in autumn.

Vaccinations

A number of effective dead vaccines against influenza viruses have been available for animals for a long time , and several live vaccines have been developed to market maturity since 2005, including in China . In Germany, however, vaccination against avian influenza is only permitted in exceptional cases. There is also an approved DNA vaccine for chickens .

The World Health Organization has repeatedly warned against vaccination, as vaccinated animals can no longer be distinguished from virus-carrying animals. In addition, vaccinated, infected birds could become carriers of the virus without showing symptoms themselves. There is also the risk that the viruses will mutate in undetected infected animals and that these genetic changes could spread more easily than in non-vaccinated herds, since these would be killed after each outbreak; such a development was observed following an H5N2 outbreak in Mexico . Nevertheless, on October 20, 2005, the EU called on the member states to prepare vaccination programs for zoo animals. Since then, the individual German federal states have allowed zoo animals to be vaccinated, especially for rare species.

On 15 November 2005, the Director General was World Organization for Animal Health ( World Organization for Animal Health , OIE) cited in press reports that A could / H5N1 in Vietnam and Indonesia no longer be contained by there only kill animals. He therefore spoke out in favor of vaccination of the animals across the board. On the same day the People's Republic of China announced a vaccination of its entire poultry population, which according to official estimates should comprise 15 billion animals. Since the H5N1 outbreaks in Nigeria , vaccinations have also been carried out on a large scale in this region by UN organizations, as the epidemic can no longer be contained by other measures.

At the end of October 2006 it became known that a new subtype of the Fujian strain had spread in Southeast Asia since autumn 2005, and that it had displaced the virus variants known since 2003. It was detected in 12 Chinese provinces by August 2006, by which time it had already infected at least 22 people. A peculiarity of these diseases was that neither before nor afterwards in the vicinity of these people - mostly city dwellers - could foci of infection among poultry be found, so that it is unclear how the people became infected. The investigating researchers expressed concern that the vaccinations of poultry against A / H5N1, which are common in China, have favored the spread of the new subtype, as it is known that not all animals have achieved complete immunity. Viruses could have reproduced in vaccinated animals and adapted to their changed immune system through mutations.

Researchers at the University of Hong Kong headed by Yi Guan had also repeatedly taken samples of poultry in southern China that were sold in local markets. In 2004 0.9 percent of all poultry tested positive for H5N1 (but two out of 100 ducks), in June 2006, however, 2.4 percent of all poultry and 3.3 percent of ducks. The new subtype of the Fujian strain was responsible for three percent of all H5N1 infections in poultry in September 2005, but for 95 percent in June 2006. The Hong Kong researchers fear that the increasing spread of H5N1 viruses through apparently healthy poultry has significantly increased the risk of transition from poultry to humans.

The proponents of vaccinations point out that it is routinely possible to detect influenza infections in vaccinated animals with the help of an antibody test. The vaccine stimulates the animals to produce antibodies that differ slightly - but detectably - from the antibodies that the so-called wild type elicits. Such a vaccine has been used successfully in northern Italy near Verona for more than a year in the fight against H5 and H7 outbreaks. Vaccinated turkeys , according to the experience in Italy, are also much more difficult to infect with influenza viruses and, if infected, excrete far fewer viruses.

Transitions from A / H5N1 to humans

Avian flu is a zoonosis , a disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans. Transitions of the A / H5N1 from poultry to humans are currently very rare, but in the event of illness are often fatal. A / H5N1 is particularly at risk for people with intensive contact with infected animals, for example when slaughtering (handling blood and feces). According to the WHO, all children who died in Turkey at the beginning of 2006 as a result of an H5N1 infection had previously had direct contact with sick poultry.

Several transitions from person to person may have occurred, but could not be proven with absolute certainty (see some examples here ).

According to the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, there is at best a low risk of virus transmission with service water from rainwater harvesting systems and in bathing lakes. One of the reasons for this is that neither of these plays an epidemiological role in the spread of gastrointestinal diseases caused by bacteria, although such potentially pathogenic bacteria are always present in bird droppings.

Confirmed cases of illness and death

The only reliable statistics on H5N1 disease in humans are official statistics from the World Health Organization. However, especially the extremely high death rate resulting from the WHO statistics should be interpreted very cautiously, "since an unknown number of mild disease courses are not diagnosed and reported". For example, the journal Science pointed out in 2006 that neither Cambodia nor Laos had a laboratory for investigating suspected H5N1 cases in humans; Significantly, the H5N1 infection of the first Laos-born victim (a fifteen-year-old from Vientiane who died on March 7, 2007 ) was only diagnosed after she was taken to a Thai hospital. According to Nature , thousands of people die of infectious diseases every day in the rural regions of Indonesia without a precise analysis of the pathogens.

Experts also question the reliability of the number of cases reported from China . The country had only reported diseases in poultry to the WHO since mid-2003 and human diseases since the end of 2005, but in February 2003 three people from Hong Kong had contracted an H5N1 infection after visiting the Chinese province of Fujian . In June 2006, eight experts reported in a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine that in November 2003 a 24-year-old man in China had demonstrably died as a result of an H5N1 infection. In addition, tests for H5N1 have so far only been carried out in China if there have been outbreaks among animals in the immediate vicinity of the sick. In southern China, A / H5N1 has also been detectable in 2 out of 100 slaughter poultry from asymptomatic flocks since at least 2004. The only infection reported so far from America was acquired in the People's Republic of China.

At times (2014/2015), the number of new cases in Egypt was particularly high. By May 2015, 840 cases and 447 deaths had been reported to the WHO. In the following years, the number of cases increased only slightly.

For the repeated outbreaks of the disease since 2003, the statistics of the World Health Organization showed the following confirmed cases of illness in humans on May 8, 2020:

| country | Diseases | Deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Egypt | 359 | 120 |

| Azerbaijan | 8th | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 8th | 1 |

| People's Republic of China | 53 | 31 |

| Djibouti | 1 | 0 |

| Indonesia | 200 | 168 |

| Iraq | 3 | 2 |

| Canada | 1 | 1 |

| Cambodia | 56 | 37 |

| Laos | 2 | 2 |

| Myanmar | 1 | 0 |

| Nepal | 1 | 1 |

| Nigeria | 1 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 3 | 1 |

| Thailand | 25th | 17th |

| Turkey | 12 | 4th |

| Vietnam | 127 | 64 |

| together | 861 | 455 |

Risk situation for people

Experts around the world rate the risk of people contracting an H5N1 infection to be extremely low . In particular, the number of deaths registered by the WHO must be seen in relation to the risk of dying from the effects of "common human influenza" ( real viral flu ). According to the official German cause of death statistics, up to 20,000 people die each year in Germany alone as a result of an infection with human influenza viruses.

Since 2006, the WHO has assigned the A / H5N1 pathogen the pandemic warning level Alert phase ("alarm phase") (until June 2013: pandemic warning level 3), which is defined by the fact that a new influenza subtype in rare individual cases is human transmitted to human; this assignment remained in place in 2009 after the occurrence of the so-called swine flu ( influenza A virus H1N1 ).

However, many experts fear that the bird flu virus could cross with a human flu pathogen. In principle, this would be possible if, for example, pigs, poultry or humans are simultaneously infected with A / H5N1 and a human flu pathogen (mostly A / H1N1 or A / H3N2 ). In this way, a new virus subtype with changed properties could arise. It would then be conceivable that this new type of virus could more easily pass from animal to person or even from person to person. Since, for example, the influenza A / H1N1 subtype was also detected in ducks, u. a. A / Duck / Alberta / 35/76 (H1N1), poultry must also be considered a potential source of gene exchange for avian and human flu viruses.

In principle, however, a massive direct transfer of influenza viruses from birds to humans is also considered possible , provided that certain changes in their genetic makeup have previously occurred in the viruses. This fear is supported by the results of US researchers who reconstructed the pathogen causing the Spanish flu A / H1N1 in autumn 2005 . The scientists' findings suggested that the influenza virus A / H1N1 they reconstructed was derived directly from an avian flu virus and developed the ability to infect humans. According to these researchers, the Spanish flu did not jump over after being reassorted ("crossed") with human flu viruses, but after a few (approx. 10) mutations . Since this became known, the risk of a new pandemic influenza has been rated significantly higher. For example, Reinhard Kurth , President of the Robert Koch Institute , stated in the FAZ on August 18, 2005 : “The risk of a pandemic is real and the risk is currently higher than it has been for decades.” In January 2006, Kurth added: “ the virus mutates rapidly very much. "the Institute is Kurth According to its plans for pandemic-case assumption that in moderate pathogenicity about 30 percent of the population suffering from the flu virus of the pathogen.

At the end of March 2006, a study by Japanese and American scientists led by Kyoko Shinya from the University of Wisconsin in Madison , USA , was published in the journal Nature , which aims to explain why transmission from person to person has not yet occurred. Unlike conventional flu viruses that settle in the upper respiratory tract, the aggressive bird flu virus mainly affects the lower respiratory tract. It nests in the alveoli. This would make it more difficult for the virus to spread from person to person through coughing or sneezing, even though the pathogen can multiply well in the human lungs. Should the viruses develop the ability to colonize the upper respiratory tract, the likelihood of a pandemic could increase.

Recommendations for infection protection

The German Federal Office for Civil Protection and Disaster Aid (BBK) has published recommendations on its website for emergency services who are involved in the removal of infected animals. This includes information on self-protection when handling infectious animals or animal carcasses, as well as on the protective equipment required. If, in spite of all precautionary measures, there is direct contact with an infected animal or with its excretions, according to a recommendation by the Robert Koch Institute , “hands should be washed thoroughly with soap and water and soiled clothing should be washed in the washing machine. Even if the risk of bird flu is extremely low, a doctor should be consulted if you have flu symptoms. "

The German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has also published a “Recommendation of special measures to protect employees against infections caused by highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses” by resolution 608 of the Committee for Biological Agents and recommends, among other things, “Particle-filtering half masks FFP3” (corresponds to NIOSH N99 in the USA ) for medical personnel during the examination of sick people; If there is a lower risk of aerosol exposure ( droplet infection ), half masks of the type FFP2 (USA: NIOSH N95) or FFP1, which should not be used by several people and should be disposed of after a single use, are sufficient. The Pharmaceutical newspaper According to these masks guarantee "when used correctly, in contrast to most surgical masks a tight fit"; At the same time, it is recommended that the mouth and nose protection for sick people should also meet the requirements of device class FFP1 according to DIN EN 149. The Robert Koch Institute has also issued recommendations if the virus should actually spread massively to humans.

Recommendations for handling poultry meat

So far not a single disease of the H5N1 virus through contaminated food has become known worldwide. In Western Europe in particular, it can be assumed that so far no contaminated poultry products have come onto the market either. Additional caution when handling food, which goes beyond the hygiene that is already required to protect against salmonellosis , is therefore currently not recommended by any official body. In experiments, the highly pathogenic variant of the avian influenza virus H5N1 was inactivated in chicken breast and thigh meat after only one second at 70 ° C.

For trips abroad , however, there is a recommendation by the German Foreign Office : In areas where A / H5N1 is widespread, poultry meat and eggs should always be heated to the core above 70 ° C before consumption; In concrete terms, this means: boil eggs for 10 minutes, poultry meat must also be clearly cooked inside, i.e. no longer reddish at any point. In these areas, contact with animals that could potentially be ill should also be avoided in any case . In particular, you should avoid visiting bird or poultry markets.

No preventive use of antivirals

The Federal Foreign Office expressly does not recommend a preventive stockpiling of Tamiflu . Before a preventive administration of antiviral agents is warned by doctors also, as is H5N1 still too little is known about the biological properties of bird flu and for the effectiveness of existing drug for a possible no proof can be furnished yet to be discovered pandemic virus. Such behavior could also favor the emergence of resistant virus strains.

Vaccinations

In general, the following applies: In order for a prophylactic vaccination to be able to work reliably against a virus, its surface proteins in particular must be known. Should the currently circulating H5N1 virus mutate and therefore be able to pass more and more from person to person, this new property would probably be due to altered surface proteins. The manufacture and approval of a vaccine adapted to the changed virus could therefore only begin after the changes became known, i.e. after the start of increased human-to-human transmission.

In February 2006, after a conference of the German health ministers, they announced that agreements had been made with the German pharmaceutical industry on the rapid production of 160 million vaccine units, ie over two units per German citizen in the event of a pandemic. Based on these agreements, the rapid production of a vaccine against the so-called swine flu took place in 2009.

Although a reliable vaccine against the pathogen of a pandemic can only be produced when the emergency has already occurred, various research groups have been developing so-called prototype or model vaccines as an interim solution based on the already known variants of the H5N1 pathogen (also called a mock-up file). It is hoped that experience in dealing with the viruses will enable a vaccine against the pandemic pathogen to be produced quickly in the event of a pandemic. It is also hoped that an imperfect vaccine could also show a certain immunological effect and trigger so-called cross - reactions against the then current H5N1 variant. This “cross protection” has been repeatedly demonstrated in animal experiments; whether this will ultimately be a promising strategy is a matter of dispute. According to Hong Kong researchers, the H5N1 subtype of the Fujian strain, which has predominated among poultry in southern China since summer 2006 at the latest, is not recognized by antibodies that respond to the H5N1 strain isolated in Vietnam in 2004, which the drug companies used as the basis for their vaccine development.

A conventional flu vaccination against the "real flu" (influenza) does not protect against the A / H5N1 virus, but many experts recommend that you get vaccinated against influenza. This is especially true when traveling in H5N1-prone areas. A flu vaccination can usually stop the known human flu viruses from multiplying. In this way, a simultaneous infection with both flu subtypes can be prevented and thus a possible “crossover” of a human flu virus with A / H5N1. Such a new combination could greatly increase the risk of virus transitions from person to person and could become the starting point for a pandemic.

A vaccination against pneumococci can also be useful, especially for small children and adults aged 65 and over . These bacteria are often responsible for the pneumonia that follows a viral infection: Anyone who becomes infected with an influenza virus and dies as a result does not normally die directly from the virus, but from a secondary infection ; this is often caused by pneumococci.

However, there have been reports from Asia that many people with A / H5N1 developed acute inflammation of the lower lobes of the lungs caused directly by the virus. Two Vietnamese children are said to have died of encephalitis without showing any signs of respiratory disease.

Symptoms in humans

The incubation period of the virus A / H5N1 appears to be longer than the 2 to 3 days observed in “normal” human influenza. Data published by the World Health Organization says the incubation period is between 2 and 8 days; however, cases with an incubation period of 17 days have also been described. The WHO recommends assuming an incubation period of 7 days in epidemiological studies. Many patients with H5N1 infection developed pneumonia at an early stage.

After the onset of the illness, the following flu-like symptoms were regularly observed (see influenza ):

- extremely high fever

- to cough

- Shortness of breath

- Sore throat

Partly also diarrhea, less often stomach pain and vomiting.

Very often in the further course of the disease:

- Inflammation of the lungs ( pneumonia )

- Stomach discomfort

- Intestinal discomfort

- Increase in liver values

- severe reduction in the number of leukocytes ( leukopenia )

- severe reduction in erythrocytes ( anemia )

- severe reduction in platelets ( thrombocytopenia )

Occasionally, patients also developed kidney weakness, which later increased to complete kidney failure . Frequently, however, a fatal lung failure set in , or the sick people died of multiple organ failure . The relatively high death rate is not uncommon with novel viral diseases and can be explained by some factors. a. due to the fact that this virus is not yet adapted to humans (and therefore quickly kills its host instead of using it as a "tool" for spreading) and, secondly, humans have virtually no defenses against this virus subtype.

According to a Hong Kong research group, the viruses release certain inflammation-promoting substances ( cytokines , especially interleukin 6 ) in the lungs , which generally activate the body's immune response to invading pathogens. However, three to five times as many cytokines are released from the H5N1 viruses as from human flu viruses. This cytokine storm can quickly lead to severe toxic shock and multiple organ failure .

Treatment in humans

In June 2006 the WHO published guidelines for the drug treatment of H5N1 patients. In sick people, the antiviral neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir (trade name Tamiflu®) for intake or zanamivir (trade name Relenza®) for inhalation can help in the early stages of the disease , provided the pathogen is not resistant to these drugs.

An Australian study published in September 2007 examined several isolates of the two circulating HPAI strains from 2004 and 2005. According to this study, the sensitivity of both strains to zanamivir corresponds approximately to the sensitivity of A / H1N1 reference strains. According to these results, the susceptibility of the dominant strain in Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand to oseltamivir decreased by a factor of 6–7, whereas the sensitivity of the second, Indonesian, strain decreased by a factor of 15–30. The researchers suspect antigen drift as the cause of the increasing insensitivity.

Contingency plans in the event of a pandemic

In many countries, national contingency plans have been drawn up in the event of a massive transition from avian influenza viruses to humans. The World Health Organization dispatches investigators ("field epidemiologists ") quickly to areas in which H5N1 diseases have occurred or are suspected in humans . These try to understand the transmission routes and possible changes in the genetic makeup of the virus, often with considerable effort. In addition, many countries have considerable amounts of antiviral drugs in stock.

See also

literature

- Alan Sipress: The Fatal Strain: On the Trail of Avian Flu and the Coming Pandemic. Viking, 2009

- Michael Greger : Bird Flu. A Virus of Our Own Hatching . Lantern Books, New York 2006, ISBN 1-59056-098-1 ( full text )

- Mike Davis: Avian flu. For the social production of epidemics. Association A, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-935936-42-7 (German version of: The Monster at our Door. The Global Thread of Avian Flu. The New Press, New York, London 2005, ISBN 1-59558-011-5 )

Web links

Precautionary measures

- German Federal Office for Civil Protection and Disaster Aid: Recommendations for emergency services. (PDF)

- Recommendation of special measures to protect employees from infections caused by highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (classic avian influenza, bird flu). Resolution of the Committee on Biological Agents 608; Status: February 2007

- Occupational health and safety in the event of human influenza that is not sufficiently preventable by vaccination. Decision of the Committee on Biological Agents 609; Status: June 2012

- Federal Institute for Risk Assessment: Hygiene tips for the home and kitchen.

Important official sources

International institutions

- World Health Organization (WHO) : current overview page for H5N1 (in English)

- World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) : Avian Influenza Overview Page

- World Food Organization (FAO) : Guidelines to reduce the risk of infection with bird flu (in English, pdf; 101 kB)

- European Scientific Working group on Influenza : current, science-oriented information (in English)

In Germany

- Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture : Information on avian influenza / bird flu.

- Robert Koch Institute : Zoonotic Influenza.

- Friedrich Loeffler Institute : Risk assessment for the introduction and occurrence of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in poultry flocks in the Federal Republic of Germany. Status: June 3, 2015 (PDF)

In Austria

In Switzerland

- Federal Office of Public Health: Influenza Pandemic Plan Switzerland 2018.

- Swiss Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office: Bird flu in animals.

Other outstanding sites

- “Background information on bird flu and tips for ornithologists.” (PDF, 827 KB), published in: Vogelwarte. Ornithology Journal. Volume 43, 2005, pp. 249-260.

- Foreign animal diseases, the gray book. ( Memento from March 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Study by the Committee on Foreign Animal Diseases of the US Animal Health Association from 2008 (PDF; 4.6 MB)

- Fowl play. The poultry industry's central role in the bird flu crisis. ( Memento from July 15, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) PDF, 430 kB. Agricultural policy background page of the NGO GRAIN , Barcelona, February 2006.

Materials for school

- learn-line.nrw.de : Background information, news and statistics in the NRW education server

- lernarchiv.bildung.hessen.de : freely accessible materials on the Hessen education server

- ZUM-Wiki: Teaching materials

- FIZ CHEMIE Berlin : a very detailed, illustrated online course (menu navigation at the top right)

- “Bird flu” dossier from WOZ : critical agricultural policy background texts and country reports on bird flu

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Recommendations of the Robert Koch Institute on prevention and control measures for residents with suspected or proven influenza in homes. On: rki.de , as of August 2010

- ↑ Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza outbreaks in poultry and in humans: Food safety implications. (PDF; 206 kB) . WHO and FAO of November 4, 2005

- ↑ Avian influenza / avian influenza. ( Memento of March 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Leaflet of the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office (FVO), status 03/2011

- ↑ In: New Scientist, May 13, 2006, p. 39

- ↑ In: Science . Volume 312 of June 9, 2006, p. 1451

- ↑ Key Facts About Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus. On: cdc.gov of November 21, 2010. It says literally: “These influenza A viruses occur naturally among birds. Wild birds worldwide get flu A infections in their intestines, but usually do not get sick from flu infections. "

- ↑ Noriyuki Yamaguchi et al .: Satellite-tracking of Northern Pintail Anas acuta during outbreaks of the H5N1 virus in Japan: implications for virus spread. In: Ibis. Volume 152, No. 2, pp. 262-271, doi: 10.1111 / j.1474-919X.2010.01010.x

-

↑ Qiqi Yang, Xiang Zhao et al .: Assessing the role of live poultry trade in community-structured transmission of avian influenza in China. In: PNAS. Online advance publication of March 2, 2020, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1906954117 .

Avian influenza and live poultry trade in China. On: eurekalert.org of March 2, 2020. - ↑ In: Science. Volume 311 of March 3, 2006, p. 1225

- ↑ according to New Scientist of May 19, 2007, p. 12

- ↑ Chairul A. Nidom et al .: Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses from Pigs, Indonesia. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 16, No. 10, October 2010, doi: 10.3201 / eid1610.100508

- ↑ D. Cyranoski: Bird flu data languish in Chinese journals . In: Nature . 430, No. 7003, 2004, p. 955. doi : 10.1038 / 430955a .

- ↑ Update on Hyghly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Animals (Type H5 and H7). Overview of diseases of wild and domestic poultry. On: oie.int of October 16, 2010

- ↑ "Poultry trading is the primary means of spreading the virus." This is a quote from Scott Newman, expert on animal health at the FAO , quoted in: Science. Volume 319, 2008, p. 1178

- ↑ S. Lorenzen: Evolution and spread of the bird flu virus H5N1 Asia and aspects of biosecurity . In: Veterinary survey. Volume 63, 2008, pp. 333–339, full text (PDF; 125 kB)

- ↑ Did the bird flu come from Hungary by truck? Deliveries to British turkey farm shortly before the outbreak of the disease. ( Memento of September 27, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) NABU, February 12, 2007

- ^ In: New Scientist, May 13, 2006, p. 41

- ↑ In: Science. Volume 319, 2008, p. 1178

- ↑ In: Science. Volume 312, May 12, 2006, p. 845

- ↑ Immediate notification report (Ref OIE: 7695). On: oie.int of January 16, 2008 (PDF; 19 kB)

- ↑ Immediate notification report. REF OIE 13447, Report Date: 13/05/2013, Country: Korea (Dem. People's Rep.) (PDF; 48 kB) On: oie.int of May 13, 2013

- ↑ Follow-up report No. 8. Reference OIE: 13510. (PDF; 84 kB) On: oie.int of May 26, 2013

- ↑ OIE: Weekly Disease Information , Volume 20, No. 8, February 22, 2007

- ^ In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. No. 153 of 6 July 2006, p. 18

- ^ OIE: Immediate notification report. dated January 20, 2015, REF OIE 17014, Report Date: 20/01/2015, Country: United States of America

- ↑ Report reference: REF OIE 16771, Report Date: 16/12/2014, Country: United States of America. On: oie.int , December 16, 2014

- ↑ OIE: Report of April 15, 2015 , Information received on April 15, 2015 from Dr John Clifford, Deputy Administrator, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington.

- ↑ Report reference: CAN-2015-NAI-001 REF OIE 17152, Report Date: 06/02/2015, Country: Canada. On: oie.int , February 7, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas C. Mettenleiter , Elke Reinking: Animal health also concerns people. Example bird flu. In: Research Report. No. 1/2008, p. 12. Braunschweig, ISSN 1863-771X

- ↑ Vincent J. Munster et al .: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variation in Prevalence of Influenza A Viruses in Wild Migratory Birds. In: PLoS Pathog . Volume 3, No. 5: e61, doi: 10.1371 / journal.ppat.0030061

- ↑ New vaccine against bird flu developed. On: taz.de from December 28, 2005:

- ↑ Seyed Davoud Jazayeri and Chit Laa Poh: Recent advances in delivery of veterinary DNA vaccines against avian pathogens . In: Veterinary Research . tape 50 , no. 1 , October 10, 2019, p. 78 , doi : 10.1186 / s13567-019-0698-z , PMID 31601266 , PMC 6785882 (free full text).

- ↑ In: FAZ . No. 254, Nov. 1, 2006, p. N1 (Nature and Science) , based on information from Robert Webster, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee

- ↑ In: New Scientist of November 4, 2006, p. 8 f.

- ↑ GJD Smith et al .: Emergence and predominance of an H5N1 influenza variant in China. In: PNAS . Volume 103, No. 45, 2006, pp. 16936-16941, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0608157103 . During the control examinations between June 2005 and June 2006, 3.5% of the geese, 3.3% of the ducks and 0.5% of the chickens were infected with H5N1; a total of 53,220 animals were tested.

- ↑ Maria D. Van Kerkhove et al .: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (H5N1): Pathways of Exposure at the Animal ‐ Human Interface, a Systematic Review. In: PLoS ONE. Volume 6, No. 1: e14582, 2011, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0014582

- ↑ Martin Enserink: Controversial Studies Give a Deadly Flu Virus Wings. In: Science. Volume 334, No. 6060, 2011, pp. 1192–1193, doi: 10.1126 / science.334.6060.1192

- ^ Richard Stone: Combating the Bird Flu Menace, Down on the Farm. In: Science. Volume 311, 2006, p. 945, doi: 10.1126 / science.311.5763.944

- ^ Declan Butler: Pandemic 'dry run' is cause for concern. In: Nature. Volume 441, 2006, pp. 554-555, doi: 10.1038 / 441554a

- ↑ In: The New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 354, pp. 2731 f. dated June 22, 2006

- ↑ H. Chen et al .: Establishment of multiple sublineages of H5N1 influenza virus in Asia: Implications for pandemic control. In: PNAS. Volume 103, 2006, pp. 2845-2850; doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0511120103

- ↑ a b cdc.gov of January 8, 2014: First Human Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Infection Reported in Americas.

- ↑ Egypt: upsurge in H5N1 human and poultry cases but no change in transmission pattern of infection. On: emro.who.int from May 15, 2015

- ↑ Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A (H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2015. On: who.int from May 1, 2015

-

↑ Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A (H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2020. On: who.int of May 8, 2020.

For an overview see also: Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) reported to WHO. -

↑ who.int : Situation updates - Avian influenza.

who.int : Monthly Risk Assessment Summary: Influenza at the Human-Animal Interface. - ↑ Information on Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Identified in Human in Nepal. On: searo.who.int/ from May 2, 2019

- ↑ Current WHO global phase of pandemic alert: Avian Influenza A (H5N1). From: who.int , accessed July 15, 2015

- ^ Jeffery Taubenberger et al .: Initial Genetic Characterization of the 1918 "Spanish" Influenza Virus. In: Science. Volume 275, 1997, pp. 1793-1796; doi: 10.1126 / science.275.5307.1793

- ↑ Deadly birds. The avian flu spread pretty directly to humans as early as 1918. On: heise.de from October 7, 2005

- ↑ Bird flu - information for emergency services. (PDF) German Federal Office for Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance, as of February 24, 2006

- ↑ Recommendation of special measures to protect employees from infections caused by highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Resolution 608 of the German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; As of February 13, 2007

- ↑ NIOSH-Approved Disposable Particulate Respirators (Filtering Facepieces). In: cdc.gov/niosh , accessed on 11 October 2012

- ↑ Pandemic influenza: Not all masks are the same. On: pharmische-zeitung.de , accessed on October 11, 2012. It explains the following: “The FFP masks are available in three protection levels, with FFP1 filters at least 80 percent, FFP2 filters 94 percent and FFP3 filters 99 percent with a NaCl test aerosol. A maximum of 22, 8 or 2 percent of the aerosol may reach the wearer. "

- ^ P. De Benedictis, MS Beato and I. Capua: Inactivation of Avian Influenza Viruses by Chemical Agents and Physical Conditions: A Review . In: Zoonoses and Public Health . Volume 54, 2007. pp. 51-68, here p. 55

- ^ Avian influenza: food safety issues. From: who.int , accessed August 9, 2019

- ↑ John J. Treanor et al. a .: Safety and Immunogenicity of an Inactivated Subvirion Influenza A (H5N1) Vaccine . In: The New England Journal of Medicine . 354, No. 13, 2006, pp. 1343-1351. , Full text

- ↑ In: New Scientist, November 4, 2006, p. 9

- ↑ Avian influenza - Key facts. On: who.int , as of March 2014

- ↑ JR Tisoncik, MJ Korth u. a .: Into the eye of the cytokine storm. In: Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. Volume 76, number 1, March 2012, pp. 16-32, doi : 10.1128 / MMBR.05015-11 , PMID 22390970 , PMC 3294426 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ Similar findings were reported from the Hospital for Tropical Deseases , Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: Menno de Jong et al .: Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. In: Nature Medicine. Volume 12, 2006, pp. 1203-1207, doi: 10.1038 / nm1477

- ↑ WHO Rapid Advice Guidelines on pharmacological management of humans infected with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. (PDF; 1.2 MB) On: who.int , status: 2006

- ↑ JL McKimm-Breschkin et al .: Reduced Sensitivity of Influenza A (H5N1) to Oseltamivir. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases. Volume 13, No. 9, 2007, pp. 1354-1357, doi: 10.3201 / eid1309.07-0164 , full text